Organisational Behaviour Textbook, Fifth Edition

advertisement

Organisational Behaviour

Fifth Edition

Organisational Behaviour

Fifth Edition

This page intentionally left blank

Organisational Behaviour

Fifth Edition

Knud Sinding and Christian Waldstrom

Mc

Graw

Hill

Education

London Boston Burr Ridge, IL Dubuque, IA Madison, WI New York San Francisco

St. Louis Bangkok Bogota Caracas Kuala Lumpur Lisbon Madrid Mexico City

Milan Montreal New Delhi Santiago Seoul Singapore Sydney Taipei Toronto

Organisational Behaviour, Fifth Edition

Knud Sinding and Christian Waldstrom

ISBN-13 9780077154615

ISBN-10 0077154606

Mc

G raw

Hill

Education

Published by McGraw-Hill Education

Shoppenhangers Road

Maidenhead

Berkshire

SL6 2QL

Telephone: 44 (0) 1628 502 500

Fax: 44 (0) 1628 770 224

Website: www.mcgraw-hill.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

The Library of Congress data for this book has been applied for from the Library of Congress

Acquisitions Editor: Peter Hooper

Production Editor: James Bishop

Marketing Manager: Alexis Gibbs

Cover design by Adam Renvoize

Printed and bound in [country] by [insert printer, City]

Published by McGraw-Hill Education (UK) Limited an imprint of McGraw-Hill Education, Inc., 1221 Avenue of

the Americas, New York, NY 10020. Copyright © 2014 by McGraw-Hill Education (UK) Limited. All rights

reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored

in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education, including, but

not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning.

Fictitious names of companies, products, people, characters and/or data that may be used herein (in case

studies or in examples) are not intended to represent any real individual, company, product or event.

ISBN-13 9780077154615

ISBN-10 0077154606

© 2014. Exclusive rights by McGraw-Hill Education for manufacture and export. This book cannot be re-exported

from the country to which it is sold by McGraw-Hill Education.

Dedication

For Paul Christian and Martin Andreas,

and for Julie and Jonathan - our kids.

Brief Table of Contents

Detailed Table of Contents

Case Grid

Preface

Acknowledgements

Guided tour

Technology to enhance learning and

teaching

Custom Publishing Solutions: Let us

help make our content your solution

Make the grade!

1

Part 1

The world of organisational behaviour

Foundations of organisational behaviour and research

vii

xi

xiii

xiv

xvi

xix

xx

xxi

1

3

Part 2

Individual processes

2 Personality dynamics

3 Values, attitudes and emotions

4 Perception and communication

5 Content motivation theories

41

43

89

126

184

6 Process motivation theories

218

Part 3

Group and social processes

7 Group dynamics

8 Teams and teamwork

9 Organisational climate: diversity and stress

Part 4

Organisational processes

10 Organisational structure and types

11 Organisational design: structure, technology and effectiveness

12 Organisational and international culture

13 Decision-making

14 Power, politics and conflict

15 Leadership

16 Diagnosing and changing organisations

Glossary

Index

265

267

298

341

381

383

415

4-49

484

520

566

598

635

647

Detailed Table of Contents

Case Grid

Preface

Acknowledgements

Guided tour

Technology to enhance learning and

teaching

Custom Publishing Solutions: Let us

help make our content your solution

Make the grade!

Part 1: The world of organisational behaviour

1 Foundations of organisational behaviour

and research

Opening Case Study: Christmas snow

in the Channel Tunnel

1.1 The history of organisational behaviour

1.2 A rational-system view of

organisations

1.3 The human relations movement

1.4 Alternative and modern views

on organisation studies

1.5 Organisational metaphors and

modern organisation theory

1.6 Learning about OB from theory,

evidence and practice

1.7 Research methods in

organisational behaviour

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

Part 2: Individual processes

2 Personality dynamics

Opening Case Study: Narcissistic

personality leaders

2.1 Self-concept: the I and me in OB

2.2 Self-esteem: a controversial topic

2.3 Self-efficacy

2.4 Self-monitoring

2.5 Locus of control: self or

environment?

xi

xiii

xiv

xvi

xix

xx

xxi

1

3

4

5

8

15

18

21

26

31

34

35

36

37

41

43

44

45

47

49

52

53

2.6

2.7

2.8

2.9

Personality

Personality types

Abilities and styles

Psychological tests in the

workplace

2.10 Cognitive styles

2.11 Learning styles

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

55

58

62

3 Values, attitudes and emotions

Opening Case Study: Why insensitivity

is a vital managerial trait

3.1 Values

3.2 Attitudes and behaviour

3.3 Job satisfaction

3.4 Flow in the workplace

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

89

4 Perception and communication

Opening Case Study: Wobbly Wheels:

Rarobank, cycling and drugs

4.1 Factors influencing perception

4.2 Features of perceived people,

objects and events

4.3 A social information-processing

model of perception

4.4 Attributions

4.5 Self-fulfilling prophecy

4.6 Communication: the input to

perception

4.7 Interpersonal communication

4.8 Organisational communication

patterns

4.9 Strategic and asymmetric

information

65

67

71

76

78

78

80

90

90

97

101

111

114

116

116

117

126

127

129

129

134

138

145

148

153

161

166

Detailed Table of Contents

4.10 Dynamics of modern

communication

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

168

172

175

175

178

5 Content motivation theories

Opening Case Study: Societe Generale

and the motivation of Jerome Kerviel

5.1 What does motivation involve?

5.2 Needs theories of motivation

5.3 Integration of need theories

5.4 Job characteristics and the

design of work

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

184

6 Process motivation theories

Opening Case Study: Bonuses for

bankers

6.1 Expectancy theory of motivation

6.2 Equity theory of motivation

6.3 Motivation through goal setting

6.4 Understanding feedback

6.5 Organisational reward systems

6.6 Putting motivational theories

to work

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

218

Part 3: Group and social processes

7 Group dynamics

Opening Case Study: A retrospective

of the Challenger Space Shuttle

disaster — was it groupthink?

7.1 Groups

7.2 Social networks

7.3 Tuckman's group development

and formation process

185

186

190

204

205

210

211

212

213

219

220

225

231

237

245

252

253

255

255

257

265

267

268

270

273

275

7.4

7.5

7.6

7.7

Roles

Norms

Group size and composition

Homogeneous or

heterogeneous groups?

7.8 Threats to group effectiveness

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

278

280

283

8 Teams and teamwork

Opening Case Study: Miracle on

the Hudson

8.1 Team effectiveness

8.2 Team roles and team players

8.3 Work-team effectiveness:

an ecological model

8.4 Team building

8.5 Effective teamwork through

co-operation, trust and

cohesiveness

8.6 A general typology of work teams

8.7 Teams in action: quality circles,

virtual teams and self-managed

teams

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

298

9 Organisational climate: diversity

and stress

Opening Case Study: Real partners

simply do not get sick

9.1 Organisational climate

9.2 Stereotypes and diversity

9.3 Stress and burnout

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

Group exercise

284

285

289

290

290

292

299

300

303

305

309

312

315

318

328

329

329

331

341

342

343

345

354

368

370

370

372

373

375

Detailed Table of Contents

Part 4: Organisational processes

10 Organisation structure and types

Opening Case Study: Siemens scandal and restructuring

10.1 Organisation - defined,

described and depicted

10.2 Elements of organisation

structure

10.3 Organisational forms

10.4 Organisation types

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review QUestans

Personal' awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

11 Organisational design: structure,

technology and effectiveness

Opening Case Study: Keeping Nokia

fit or shooting in the dark

11.1 Organisational fit

11.2 The contingency approach to

organisation design

11.3 Organisational effectiveness

11.4 Organisational decline

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Revievh, 41:lye stormPersorpM awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

12 Organisational and international culture

Opening Case Study: Seoul machine

12.1 Culture and organisational

behaviour

12.2 Organisational culture

12.3 The organisational socialisation

process

12.4 Intercultural differences

12.5 Hoisteders cultural dimensions

12.6 Fans Trornpenaars' cultural

dimensions

12.7 Cultural perceptions of time,

space and communication

12.8 The global manager and

expatriates

381

383

384

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Persona! awareness and growth. exercise

Group exercise

476

477

477

479

385

387

392

397

409

410

410

412

415

415

417

418

432

438

440

442

442

444

449

450

450

453

460

463

465

467

469

472

13 Decision-making

Opening Case Study: The Gulf of

Mexico oil spill

13.1 Models of decision-making

13.2 Dynamics of decision-making

13.3 Group decision-making and

other forms of participation

13.4 Group problem-solving and

creativity

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Persona! awareness and growth exercise

Group ex erase

484

485

486

492

500

505

511

512

513

514

14 Power, politics and conflict

Opening Case Study: The Stanford

prison experiment

14.1 Organisational influence

14.2 Organisational conflice

14.3 Social power

14.4 Organisational politics

14.5 Impression management

14.6 Empowerment

14.7 Delegation, trust and personal

initiative

Learriing outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Persona! awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

520

15 Leadership

Opening Case Study: Sweaty feet with style, not stink

15.1 What is leadership?

15.2 Trait theories of leadership

15.3 Behavioural and styles theories

15.4 Situational and contingency

theories

566

521

522

524

538

542

545

549

553

555

557

557

568

567

569

572

574

579

Detailed Table of Contents

Part 4: Organisational processes

10 Organisation structure and types

Opening Case Study: Siemens scandal and restructuring

10.1 Organisation - defined,

described and depicted

10.2 Elements of organisation

structure

10.3 Organisational forms

10.4 Organisation types

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

11 Organisational design: structure,

technology and effectiveness

Opening Case Study: Keeping Nokia

fit or shooting in the dark

11.1 Organisational fit

11.2 The contingency approach to

organisation design

11.3 Organisational effectiveness

11.4 Organisational decline

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

12 Organisational and international culture

Opening Case Study: Seoul machine

12.1 Culture and organisational

behaviour

12.2 Organisational culture

12.3 The organisational socialisation

process

12.4 Intercultural differences

12.5 Hofstede's cultural dimensions

12.6 Pons Trompenaars' cultural

dimensions

12.7 Cultural perceptions of time,

space and communication

12.8 The global manager and

expatriates

381

383

384

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

476

477

477

479

385

387

392

397

409

410

410

412

415

415

417

418

432

438

440

442

442

444

449

450

450

453

460

463

465

467

469

472

13 Decision-making

Opening Case Study: The Gulf of

Mexico oil spill

13.1 Models of decision-making

13.2 Dynamics of decision-making

13.3 Group decision-making and

other forms of participation

13.4 Group problem-solving and

creativity

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

484

485

486

492

500

505

511

512

513

514

14 Power, politics and conflict

Opening Case Study: The Stanford

prison experiment

14.1 Organisational influence

14.2 Organisational conflice

14.3 Social power

14.4 Organisational politics

14.5 Impression management

14.6 Empowerment

14.7 Delegation, trust and personal

initiative

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

520

15 Leadership

Opening Case Study: Sweaty feet with style, not stink

15.1 What is leadership?

15.2 Trait theories of leadership

15.3 Behavioural and styles theories

15.4 Situational and contingency

theories

566

521

522

524

538

542

545

549

553

555

557

557

558

567

569

572

574

579

Detailed Table of Contents

15.5 Transactional and transformational/

charismatic leadership

15.6 Additional perspectives on

leadership

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

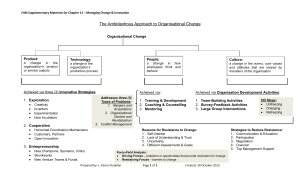

16 Diagnosing and changing organisations

Open Case Study: Oh no! First place

16.1 Forces of change

16.2 Diagnosing the need for change

584

587

590

592

592

594

598

599

602

605

16.3 Models and dynamics of

planned change

16.4 Danger: Change in progress!

16.5 Managing resistance to change

16.6 Ongoing change or organisation

development

Learning outcomes: Summary of

key terms

Review questions

Personal awareness and growth exercise

Group exercise

Glossary

Index

610

616

618

624

628

629

629

630

635

647

Case Grid

m1,11

Part 1: The World of Organisational Behaviour

1 Foundations of

organisational

behaviour

Opening Case Study: Christmas snow in the Channel Tunnel

OB in Real Life: No one best way of managing organisations

Part 2: Individual Process

2 Personality Dynamics

Opening Case Study: Narcissist Personality Leaders

OB in Real Life: Culture dictates the degree of self-disclosure in

Japan and the USA

3 Values, attitudes and

emotions

Opening Case Study: Why insensitivity is a vital managerial trait

4 Perception and

Communication

Opening Case Study: Wobbly Wheels: Rabobank, cycling and drugs

5 Content and

Motivation Theories

Opening Case Study: Societe Generale and the motivation of

Jerome Kerviel

6 Process Motivation

Theories

Opening Case Study: Bonuses for bankers

OB in Real Life: Happy feet, beautiful shoes

OB in Real life: Students at FedEx

OB in Real Life: The nuances of feedback: performance reviews

and culture

OB in Real Life: Pay practices in Britain

OB in Real Life: Rewards in China

Part 3: Group and Social Processes

7 Group Dynamics

Opening Case Study: A retrospective of the Challenger Space

Shuttle disaster: was it groupthink?

OB in Real Life: Managing groups in the World of Warcraft

8 Teams and teamwork

Opening Case Study: Miracle on the Hudson

OB in Real Life: The Israeli tank-crew study

OB in Real Life: This London company has turned corporate team

building into a circus

OB in Real Life: Liverpool FC

OB in Real Life: Stage Co

OB in Real Life: Texas Instruments

OB in Real Life: BP Norge

9 Organisational

climate: conflict,

diversity and stress

Opening Case Study: Real partners simply do not get sick

OB in real life: Fritz the Boss

OB in Real Life: Stress and death at France Telecom

Case Grid

Part 4: Organisational Processes

10 Organisation

structure and types

Opening Case Study: Siemens — scandal and restructuring

OB in Real Life: Keeping Opel independent — maybe

OB in Real Life: The Mogamma, bureaucracy Egyptian style

11 Organisational

design: structure,

technology and

effectiveness

Opening Case Study: Keeping Nokia fit or shooting in the dark

OB in Real Life: Sir Stelios and the battle for EasyJet

OB in Real Life; Strategically choosing social responsibility

at Patagonia

OB in action: Royal Dutch Shell

OB in Real Life: Lego's second coming

12 Organisation and

international culture

Opening Case Study: Seoul machine

13 Decision making

The Gulf of Mexico oil spill

OB in Real Life: Dress code at Apple

OB in Real Life: 'Put jam in your pockets, you are going to be toast'

OB in Real Life: Incrementally creating the sick note

14 Power, politics and

conflict

Opening Case Study: The Stanford prison experiment

OB in Real Life: Ferdinand and Wolfgang — and Wendelin

OB in Real Life: Nasty people at work

OB in Real Life: Being social at work

OB in Real Life: Winning moves

15 Leadership

Opening Case Study: Sweaty feet — with style, no stink

OB in Real Life; Ernst & Young

OB in Real Life: Hewlett-Packard

OB in Real Life; Richard Branson

OB in Real Life: Saatchi and Saatchi

16 Diagnosing and

Changing

Organisations

Opening Case Study: Oh, no! First place

OB in Real Life: Asda

OB in Real Life: Boehringer Ingelheim

OB in Real Life: Bang & Olufsen

Preface

This is the second time we've been involved with Organisational Behaviour. Working on the

previous edition was an honour and, whilst we did make a large number of changes and replaced

a lot of cases, we felt that we should stick closely to the existing structure. Revisiting the text to

prepare this fifth edition, however, has been a different experience altogether. With the benefit

of hindsight, and invaluable feedback from our colleagues and students, we've been able to take

a more objective look at what was working and what wasn't.

As before, our main challenges has been how to strike a balance between keeping the core of the

text true to what our readers have come to expect and how to adapt to review feedback. With this

in mind we have streamlined the chapter that used to be on Change and Knowledge to make it

easier to understand and use — but the core content that students need remains. We have removed

the focus from Knowledge Management to allow room to explore how students can analyse and

implement change and this is reflected in the new chapter title 'Diagnosing and Changing

Organisations'. While we appreciate the importance of Knowledge Management, this is a topic

usually covered in more specialised courses and rarely in the introductory level courses on organisations for which this book is designed.

This change to Chapter 16 also reflects one of the ways we've enhanced the application of

material. This chapter now has diagnosis in the title and it begins with a long section that deals

with analytical or diagnostic challenges related to each of the main chapters (or sets of chapters).

The logical progression is that it makes no sense to consider any aspect of organisational change if

it is not preceded by a diagnosis. It's a long version of `if it ain't broke, don't fix it': managers or

leaders must be able to pinpoint where the organisation is broken before they start changing it.

We also found that the chapter on corporate responsibility wasn't widely used so it has been

removed from this edition to allow a focus on more key topics.

It's also worth noting that we have moved coverage of Conflict from Chapter 9 'Organisational

Climate' to Chapter 14 'Power, Politics and Conflict' where we feel it has a more logical fit.

As you would expect, this edition of Organisational Behaviour retains a strong European focus

with full acknowledgement that many of the theories within the field are American, thus striving

for a balance between theories from both sides of the Atlantic.

For this edition, as in the fourth, we've focused strongly on updating cases throughout the book

in order to put theories into contemporary perspectives that are more likely to resonate with

students and enhance their engagement with the subject. Cases now include The Gulf of Mexico

oil spill, Royal Dutch Shell, and FedEx to name a few.

L(

[

,( ($

c

( (

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the following reviewers for their comments at various stages in the text's

development:

Joost Backer, Radbound University, Nijmegen

Conny Droge-Pott, Hanze University of Applied Sciences, Groningen

John Hassard, University of Manchester

Anni Hollings, Stafforshire University

Kent Wickstrom Jensen, University of Southern Denmark

David Spicer, Bradford University

Every effort has been made to trace and acknowledge ownership of copyright and to clear permission for material reproduced in this book. The publishers will be pleased to make suitable

arrangements to clear permission with any copyright holders whom it has not been possible to

contact.

This page intentionally left blank

Guided Tour

ona I

Learning Outcomes

When you finish studying the material in this chant,

explain what self-esteem is and how it can be imp

define self-efficacy and explain its sources

(711traSt high and law self -rnonieming individuals an •

explain the difference between an internal and an err s

23 identify and describe the Big rive personality dimes

P desenbe Jung 's and Myers and Briggs' personality

21 elaborate on cautions and tips concerning (person

a describe the implications of intelligence and cogs:

describe cognitive style" am:licensin g styles

Learning Outcomes

Each chapter opens with a set of learning

outcomes that pinpoint the key concepts

introduced.

Opening Case study

Each chapter opens with an

interesting and relevant case study to

introduce and apply key theories in OB.

Each case study contains questions to

encourage discussion.

Opening Case Study: Why insensitvity is a vital man

When Bash veTtuta <ark... !an Meultan

asked

an i

trungmt character nit, he replied: 'Detamination, curiosity and

first two are Likely m reach the rep 10 of leadenhip traits, . do nut

hersidedas a personal streng th

Hut his vrypisent is fairly StroiShtforward,Mile sensitivity and

been praised In the last Made as easemial management nits, the

tengicting ) evidence that they are actually posit. traits - especially

Perhaps imensiliWty Is essential to. survival in business7According

'lets, sleep when othera

Any leader will have to take dad

the the bast of thecenthany and the sestet.: employees helpyoutakethatsecevt,.v decision without losin g sissy over it

Imensiii. Leaders Rave got a bad reputation bucaure their

Wins. but at Least, they aTe a let simpler to enders Lana an •

urse, there are times when sensitivity and e

know this and ...TLC the t

caw of while they sake eR

Glossary

A

Ability Stable characteristic

responsible for a person's

maximum physical or

mental performance.

Accommodator Learning style

referring learning throu

rand feeling.

Alte

Key Terms

Each new term introduced in the book is

defined in the text and highlighted to

indicate this. A complete list of key terms

is provided in the glossary at the end of

the book.

Critical thinking questions

Critical thinking boxes have been added

throughout the chapters to encourage

debate and discussion among students and

to foster critical thinking skills.

on goal, even w

ong a somewhat different

tyles are needed as work groups

The practical punch line here is th,

leadership style to a participative and

Critical thinking

Are the phases proposed by Tuckman

7.4 Roles

ies have passe

Activity

Are you an optimist or a p

Instructions

Indicate for

each of the following

1 In uncertain times, I usuall

2 It's easy for me to relax

3 If something can go wr

4 I always look on th

I'm always o

Activities

Activities are interspersed

throughout the text to encourage

analytical thinking and to develop skills

through interactive tasks.

Guided bur

ouldbeaim

own..atinh', uroduc.,

Bang & 0Oursen

When the world was hit loy the financial crisis in 20

Danish producer of high.tech, high.fidelicysudioRang & Olufcm (13.k0) suffered tremendous losses

encl. a lot of new product development was dlaconci

implemented PO9itiVP 94.319 are now al,G.31711, and s

for Luxury brands. have taken off nicely. Whether o

through this crisis. only time will tell

This is not the first rime the company has been

compoaty had been at the forefront of design inn

founders o! the company. 'lawyer, tlut angina]

earced the .mp.ny mush acclaim - carried

design funseien came to relgn over everything

Sayjng 'no' to a new product from the desoccur to anyone hoping to stay

cry won one d.esign pri

OB in Real Life boxes

These mini cases provide examples from

around the globe, focusing on the differences

in perceptions, cultures and beliefs that affect

behaviour in the workplace, providing

relevant and interesting insights and an

international outlook on OB.

'HR' icons

Look out for 'HR' icons which appear in the

margin of the page whenever there is a link to

HR in the text. This acknowledges the

relationship between the two closely-related

disciplines and demonstrates where

they overlap.

managers e tarc/ookingac work design, what nu

Learning outcomes: Summary of key terms

Define the teem motivation

P4.clivaten inlefined. thoseprafesslenal -praesoes C. cause

otvokmtary. goel.oriented actions. Inployers need to under

If they are to suocessfuLly guide employees rewards eccomp

The hiuturie.nouto of nmodernumtivaiou then

Viva ways of explaining behaviour - needs, rei nforcemc

feelings/em..nue - underlie the evolution of modern

eosin of mocnatlon focus on internal energisers oi

lings/emocions Other mofivadon theories, which

oh characteriseks, tons on more complex

venally accepted theory of suofivat Between content and p

What a your nermonmakirpg style?

CbjediYes

Intooluthan

.Lyied nry luny.

a .4, 1:1.1,1dusn value un.di

,nd

ti:: Or

1,or,rtur.ity for you to no,esssnd intetrnty.r4ci

0 Applications of cognitive styles

Cognitive styles are increasingly seen

Cognitive styles may be one of the

respond appropriately across a variety

Cognitive styles are useful for the

help to identify a cognitive climate

stance and to foster tolerance h

nitivs styles sigiufic

nd and

Learning Outcomes: Summary of

Key Terms

At the end of each chapter, a short recap

reinforces and clarifies the chapter learning

outcomes.

Review Questions

These end of chapter exercises test

understanding of core theories and can be

used in class or as an assessment. As well as

checking comprehension, the exercises

require you to demonstrate your analytical

abilities by citing examples and applications

of the concepts in the chapter.

1.7) Personal awareness and growth exercise

s tends to .e

group in which they fin

he more inward and they wi

groups will be seen as distant to the

would be outgoing and lively and ima

crol, escape or symp

e most effective method of copm

raise Oue5-bOn6

1 Flow wouldyon soot nereotyoiht,

2 Which ache -barriers co managing diversity would

3 E lave you seen any evidence that diversity is a comp.

4 WhIch stress factors expcnenced by students are undc

5 Describe the stress 5,7,601115 yOLL have observed in ot

6 Why would peep]: in the helping professions become

in other occupacions?

7 Whkh kinds of nodal support are most easytaubrai

8 A natural &saner like in earthquake or a cocana cot

roping poss[ble

Flaye you ever felt that the climate In an m.10

Eat do run attribute this to?

Exercises

A variety of different exercises at the ends of

chapters illustrate decisions one might face in

the workplace. They develop ethical

awareness, transferable skills and group

discussion.

Technology to enhance learning

and teaching

OM) ,

LearningCentre

Online Learning Centre

www.mcgraw-hill.co.uk/textbooks/sinding

Students- Helping you to Connect, Learn and Succeed

We understand that studying for your module is not just about reading this textbook. It's also about

researching online, revising key terms, preparing for assignments, and passing the exam. The website

above provides you with a number of FREE resources to help you succeed on your module, including:

• Self-test questions to prepare you for mid term

tests and exams

ORGANISAliONAL 6 if4A

tea..

• Glossary of key terms to revise core concepts

"

'

gt:treit

MIalsT:M=MITarrq=s4

ledwit,..nn Wenn. vn.a.me. VVVc urantisr......1riesk.

ca,niM

o'N.R wr, auk..

• ..

ve

910.625ed

a.

h tin tmsnesa enymarnigrt

• Web links to online sources of information to help

you prepare for class

• R. tall al 11Reenat.

01.111. Wra- .

1:1101.411 te.11-13,■

-

• .11,9

-TY 0,1 fle.yrdWleral M-1,10.V1.11.,. &A.m.

•

Id

• Internet exercises

MS! ..17e.l.ntMine

• Nolocr.....4.

0.11.:011■10,1HOW

lie/ re rm.

1:111.1np elasiberec and .z.t. Isar-a

1116110.1.....117.11.41.

• win Lie*, mn Pc.ee cora, Ire. a.. the ■Ohe er.rdn.N.,

Lecturer support- Helping you to help your students

The Online Learning Centre also offers lecturers adopting this book a range of resources designed

to offer:

• Faster course preparation- time-saving support for your module

• High-calibre content to support your students- resources written by your academic peers,

who understand your need for rigorous and reliable content

• Flexibility- edit, adapt or repurpose; test in EZ Test or your department's Course Management

System. The choice is yours.

The materials created specifically for lecturers adopting this textbook include:

• Lecturer's Manual to support your module preparation, with case notes, guide answers, teaching tips

and more

• Lecture Outlines

Technology to enhance learning and teaching

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

PowerPoint presentations to use in lecture presentations

Image library of artwork from the textbook

Chapter Summaries

Case studies from previous editions

Test Bank

Essay Questions

Supplementary Lecturettes

To request your password to access these resources, contact your McGraw-Hill Education

representative or visit www.mcgraw-hill.co.uk/textbooks/sinding

TEST 11 INE

Test Bank available in McGraw-Hill EZ Test Online

A test bank of hundreds of questions is available to lecturers adopting this book for their module

through the EZ Test online website. For each chapter you will find:

• A range of multiple choice, true or false, short answer or essay questions

• questions identified by type, difficulty, and topic to help you to select questions that best suit

your needs

McGraw-Hill EZ Test Online is:

• Accessible anywhere with an internet connection — your unique login provides you access to all

your tests and material in any location

• Simple to set up and easy to use

• Flexible, offering a choice from question banks associated with your adopted textbook or allowing

you to create your own questions

• Comprehensive, with access to hundreds of banks and thousands of questions created for other

McGraw-Hill titles

• Compatible with Blackboard and other course management systems

• Time-saving- students' tests can be immediately marked and results and feedback delivered

directly to your students to help them to monitor their progress.

To register for this FREE resource, visit www.eztestonline.com

Mc

Graw

Hill

Education

create

Let us help make our content your solution

At McGraw-Hill Education our aim is to help lecturers to find the most suitable content for their

needs delivered to their students in the most appropriate way. Our custom publishing solutions

offer the ideal combination of content delivered in the way which best suits lecturer and students.

Our custom publishing programme offers lecturers the opportunity to select just the chapters or

sections of material they wish to deliver to their students from a database called CREATE' at

www.mcgrawhillcreate.co.uk

CREATE" contains over two million pages of content from:

•

•

•

•

textbooks

professional books

case books - Harvard Articles, Insead, Ivey, Darden, Thunderbird and BusinessWeek

Taking Sides - debate materials

Across the following imprints:

•

•

•

•

McGraw-Hill Education

Open University Press

Harvard Business Publishing

US and European material

There is also the option to include additional material authored by lecturers in the custom product this does not necessarily have to be in English.

We will take care of everything from start to finish in the process of developing and delivering a

custom product to ensure that lecturers and students receive exactly the material needed in the

most suitable way.

With a Custom Publishing Solution, students enjoy the best selection of material deemed to be

the most suitable for learning everything they need for their courses - something of real value to

support their learning. Teachers are able to use exactly the material they want, in the way they

want, to support their teaching on the course.

Please contact your local McGraw-Hill Education representative with any questions or alternatively

contact Warren Eels e: warren_e els @mcgraw-hill. c om.

;IVr

Make the grade!

20Z Off any

stud 8kIlls

book!

v

cAo"s

wr

X

11

1

.

..111/

Study Skills for

The

Ultimate Study

Skills Handbook

Business and

Management

Students

The Complete

Guide to

Referencing and

Avoiding Plagiarism_

Our Study Skills books are packed with practical advice and tips that

are easy to put into practice and will really improve the way you study.

Our books will help you:

•

•

•

•

I mprove your grades

Avoid plagiarism

Save time

Develop new skills

• Write confidently

• Undertake research projects

• Sail through exams

." Find the perfect job

Special offer!

As a valued customer, buy online and receive 20% off any of our

Study Skills books by entering the promo code BRILLIANT!

jiic

www.oreAup.co.vkiSivcilSk

This page intentionally left blank

Part 1

The world of organisational

behaviour

Part content

1 Foundations of organisational behaviour and research

3

This page intentionally left blank

Chapter 1

Foundations of organisational

behaviour and research

Learning Outcomes

When you finish studying the material in this chapter, you should be able to:

12 give an overview of the different views that were a source for the development of the organisational

behaviour (0B) field

El explain Taylor's principles

El describe the five key tasks of a manager according to Fayol

Bi give Barnard's view on co-operation

El explain Simon's ideas about motivating workers and bounded rationality

El describe the four alternative views on organisation studies

si contrast McGregor's Theory X and Theory Y assumptions about employees

• describe Morgan's eight organisational metaphors

El define the term 'organisational behaviour'

_.1

CHAPTER 1 Foundations of organisational behaviour and research

Opening Case Study: Christmas snow in the Channel Tunnel

On 18 December 2009, just before the Christmas holidays, massive snowfall in southern

England and northern France severely disrupted train services. One service, in particular, was

affected, the Eurostar, which connects London to Paris, Lille and Brussels. Five trains broke

down in the tunnel due to electrical failures and passengers had to be evacuated in various ways.

The train service was suspended and many passengers were inconvenienced. The breakdowns

and subsequent failures led to a media storm, which, in turn, led to an independent inquiry.

This edited version of the executive summary tells the story:

Executive summary excerpts

On the night of 18 December 2009, snow fell in the UK, with even heavier snowfall in France. The

M20 was closed, as were a number of roads and motorways in the north of France. In these conditions,

five Eurostar trains travelling to the UK from Brussels, Paris and Marne-la-Vallee (Disneyland Paris)

broke down in the Channel Tunnel.

The first train to fail was recovered relatively quickly. The subsequent four trains then broke down in

rapid succession and passengers from two of them had to be evacuated onto Eurotunnel passenger shuttles

within the Tunnel. This was the first time this had happened in 15 years of operation in the Tunnel.

Whilst the rescue operation was carried out safely, passengers on all trains were delayed for a very

considerable period before they arrived at their destination.

Following the train failures on the Friday night (18th), Eurostar services were suspended for

three days, causing severe disruption to thousands of passengers. Over the days that followed, before

Eurostar resumed a limited service on Tuesday 22 December, over 90,000 passengers were due to

travel to and from the UK by Eurostar.

With Eurostar now having over 65% of the passenger market, even if disruption were to occur

in ideal weather conditions, it would be virtually impossible to make adequate alternative travel

arrangements to accommodate all passengers. On this occasion, the adverse weather made provision

of alternative transport all the more difficult. However, Eurostar should have been better prepared for

this scale of disruption and reacted earlier to try to help passengers caught up in the delays. The

fact remains that Eurostar did not have a plan in place and had to improvise, and its provision of

information to customers was inadequate.

In the main, the evacuation of the trains was carried out efficiently and in some cases creatively

by Eurotunnel and the authorities. However, the Review highlighted serious concerns about the

procedures in the Tunnel for dealing with conditions that arise on Eurostar trains when they lose

power and subsequently their air conditioning and lighting.

The Review found no reason why, even with five trains delayed in the Tunnel the passengers could

not have been evacuated in an emergency situation (which was not the case here) in a totally safe manner.

Twenty-one recommendations were made in this report, including introduction of video links

between the various control and operation centers, a better rehearsed evacuation procedure,

more training for staff and, most notably, the following:

1. We recommend that key complementary measures should be taken before the coming winter.

k.

18.2. We recommend that Eurostar should agree with SNCF that as a general rule trains should

not be left in the middle of the countryside or in a small station overnight.

1.1 The history of organisational behaviour

(---The first one is simple to the point of banality: another heavy snowfall may come along as soon

as next winter. The other clearly intelligible recommendation is 18.2, which sends a very rich

message in just a few words.

More generally, this is a case where trains broke down and thousands of passengers

were stranded in trains in the tunnel or in the countryside between Calais and Paris, or in

icy stations when they showed up for their Christmas holidays. Conditions were poor, trains

overheated, toilets stopped working and food and water ran out. Many organisations were

involved (Eurotunnel, SNCF, Network Rail, Eurostar) whose co-operation was based on contracts and agreements.

The train breakdown and all the derived effects highlight organisational problems in a

broad number of areas, including communication and specific procedures for this type of

emergency. From these overall failings follows the need for a cascade of organisational

modifications required to address each and every one of the detailed problems identified in

the report.'

For discussion

At which levels of the involved organisations is there a need for change - and how can those

responsible ensure that similar situations do not recur?

Source: Executive summary of the independent review of the Eurostar Incident: www.icpem.net/LinkClick.aspx?

Fileticket=Q6EG8pYFIeQ%3D8ctabid=1078rmid=588

1.1 The history of organisational behaviour

J

.1

It is nearly a century since Henry Ford said: 'You can destroy my factories and offices, but give me

my people and I will build the business right back up again!' Every day, business magazines come

up with new stories reporting famous chief executive officers' (CEOs') claims that their employees

are their main source of competitive advantage. The founder of Virgin, Richard Branson, said:

`There is only one thing that keeps your company alive, that is: the people you work with. All the

rest is secondary. You have to motivate people, and attract the best. Every single employee can

make a difference [. . .1 People are the essence of an organisation and nothing else!'

However, Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams, who humorously documents managerial lapses of

sanity, sees it differently. Adams rates the often heard statement 'Employees are our most valuable

asset' as top of his list of Great Lies of Management.' This raises serious questions. Is Branson an

exception, a manager who actually acts on the idea that people are the most valuable resource?

Does the typical manager merely pretend to acknowledge the critical importance of people? If

so, what are the implications of this hypocrisy for organisational productivity and employee

well-being?

A number of studies have been enlightening. Generally, they show that there is a substantial and

rapidly expanding body of evidence - some of it based on quite sophisticated methodology - of the

strong connection between how firms manage their people and the economic results they achieve.5

A study by the University of Sheffield's Institute of Work Psychology, based on extensive examination of over 100 medium-sized manufacturing companies over a seven-year period, revealed

that people management is not only critical for business performance. It is also far more important

CHAPTER 1 Foundations of organisational behaviour and research

than quality, technology, competitive strategy, and research and development in its influence on

the bottom line. The study also showed that half the firms have no individual in charge of human

resources and that more than two-thirds have no written personnel strategy. One researcher said:

`Managers placed considerable emphasis on strategy and technology, but our research suggests

that these areas account for only a small part of the differences in financial performance.'

Jeffrey Pfeffer and his colleagues from Stanford University reviewed evidence from companies

in both the USA and Germany finding that 'people-centred practices' were strongly associated

with much higher profits and significantly lower employee turnover. Further analysis uncovered

the following seven people-centred practices in successful companies:

• Job security (to eliminate fear of losing a job).

• Careful hiring (emphasising a good fit with the company culture).

• Power to the people (via decentralisation and self-managed teams).

• Generous pay for performance.

• Lots of training.

• Less emphasis on status (to build a 'we' feeling).

• Trust-building (through the sharing of critical information).'

These factors form a package deal — they need to be installed in a co-ordinated and systematic

manner rather than in bits and pieces.

Many organisations, however, tend to act counter to their declarations that people are their

most important asset. Pfeffer and his colleagues blame a number of modern management trends

and practices. For example, undue emphasis on short-term profit precludes long-term efforts to

nurture human resources. Also, excessive job cuts — when organisations view people as a cost rather

than an asset — erode trust, commitment and loyalty.' 'Only 12 per cent of the organisations',

according to Pfeffer, 'have the systematic approaches and persistence to qualify as true peoplecentred organisations, thus giving them a competitive advantage.'9 Thus, there seems to be a major

opportunity for improvement in most organisations.

The aim of this book is to help the student of organisational behaviour to become aware of the

potential in understanding the people-centred aspects of modern companies and organisations.

Some organisational behaviour issues are becoming even more challenging as the activities

of organisations become increasingly global in reach, either because outsourcing and specialisation

places activities where there is an operating advantage, or because organisations seek to pursue

opportunities wherever they may arise. Globalisation does not in itself change the way organisational behaviour works, but anyone venturing away from a well-known and well-understood context needs to appreciate that the emphasis on OB may vary depending on location. Variations can

essentially occur in any of the fields covered in this book, but some areas are more likely to be

impacted than others. This applies to motivation, culture, climate, leadership and power. Other

areas are somewhat less affected; for example, organisational design. This and other areas may,

however, be indirectly affected. For example, if decentralisation is partly based on trust, culture

and teamwork, this practice may not travel well to countries where the assumptions are different.

Sources of inspiration of organisation and organisational behaviour theories

We start our journey in the organisational behaviour field with a look at the history of the field. A

historical perspective of the study of people at work helps in studying organisational behaviour (OB),

1.1 The history of organisational behaviour

because we can achieve a better understanding of where the field of OB stands today and where it

appears to be heading by appreciating where it has been.

Throughout history, there has always been a need to organise the efforts of many people,

whether in the case of armies, city states or even larger empires. The history of modern organisational behaviour began in the early years of the Industrial Revolution.

In the nineteenth century, sociologists such as Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim and Max Weber

studied the implications of a shift from feudalism to capitalism and from an agriculture-based

society to an industrial one. Karl Marx' studied the development of the working class,' while

Emile Durkheim" studied the loss of solidarity in the new kind of society. Max Weber was the first

to study the working of organisations and the behaviour of people within organisations.' He is

especially known for his work on bureaucratic organisations (see Chapter 10). As a sociologist, he

also studied the rise of rationality in the new society and the importance of legal authority and

efficiency in industrial production in particular.

Organisation studies developed as a separate field with the birth of 'scientific management'

(see the next section on Frederick Taylor). This happened around the beginning of the twentieth

century with the founding of the first large corporations, such as Ford, General Motors and

Standard Oil. Scientific management offered a rational and efficient way to streamline production.

It is called 'scientific management' because the recommendations to companies were based on

exact scientific studies of individual situations inspired by the advances in natural sciences.

In organisations, people were only elements in the production system. This scientific approach

to organisations evolved in the second phase of industrialism,' when the factory system expanded

from simple manufacturing processes, such as textile, to more complex manufacturing ones,

such as food, engineering and iron. These complex processes required complex organisational

procedures, including control mechanisms, routinisation and, especially, intense specialisation.

Profound scientific study of the processes was required to develop complex but also highly efficient

organisation structures (for more on organisation structures, see Chapters 10 and 11). As part

of that evolution, the function of management and administrative tasks rose and expanded considerably in number.

From the late 1930s the human factor started receiving more attention but it took several

decades before the organisational behaviour field became well developed. The different sequential

and contemporary views have resulted in different ways of studying, evaluating and managing

people and organisations. Organisational behaviour developed from this human relations view as a

separate academic discipline. Below we will highlight the work of some of the major management

thinkers and explain the different views on organisations.

Later, other theoretical lenses for the study of organisations were proposed, including conflict

theory, critical complexity theory and emergence, symbolic interactionism and postmodernism.

There is sometimes confusion about the distinction between organisational behaviour and

organisational theory. This is not surprising as there is substantial overlap and many of the

concepts from one field are directly applicable in the other. Organisational behaviour is associated

with the behaviour of individuals and groups in the organisation, sometimes also called a 'micro'

perspective. Higher levels in the organisation are correspondingly referred to as 'macro' issues, and

refer to the field of organisation theory. The behavioural or 'micro' approach is sometimes seen

as more psychological in nature, whereas the 'macro' level is seen as more sociological. Both have

a number of distinct theoretical approaches and methods. Gareth Morgan, an organizational

theorist, for instance, has emphasised that there are numerous ways in which we can view

organisations. He summarised these different views in eight 'lenses' or metaphors for looking

at organisations.

CHAPTER 1 Foundations of organisational behaviour and research

This chapter concludes by presenting the ways in which we can learn more about organisational

behaviour. In addition, a topical model for understanding and managing OB is introduced.

1.2 A rational-system view of organisations

We now focus on the early days of organisational behaviour in the beginning of the twentieth

century, based on the works of Frederick Taylor, Henri Fayol and Chester Barnard.

Frederick Taylor

Frederick Taylor is one of the best-known figures in the rational-system view of organisations and

is the founding father of scientific management, a scientific approach to management in which all

tasks in organisations are analysed, routinised, divided and standardised in depth, instead of using

rules of thumb. Taylor was born into a Quaker Philadelphia aristocratic family in 1856. At that

time, Philadelphia was an important industrial region in the USA with several engineering companies - hence, providing the ideal location for the development of scientific management. The

breakthrough for Taylor came when he started to work for the Midvale Steel Company in 1878.15

Taylor made the work of labourers more efficient by increasing the speed of work and by organising the work differently. He studied each task by comparing how different workers performed the

same task. Each of the studied tasks was divided into as many subtasks as possible. The next step

was eliminating the unnecessary subtasks and timing the fastest performance of each task. The

whole task with its subtasks was then described in detail and an optimal time was attached to each

task. Workers were asked to do the task in exactly this manner and time. Each task had to be

performed in the 'one best way' allowing no freedom for workers to choose 'how' to do their

tasks. Making the work in factories more efficient was an obsession. Taylor accused workers of

deliberately working at a slower pace, known as 'soldiering'. Part of the slow working was due to the

fact that there was no management to control the workforce, who were left entirely on their own

to develop their own working methods and to use ineffective rules of thumb. Workers were also

systematically soldiering so they could just take it easy. In fact, Taylor accused them of conspiring

to work slower in order to hide how fast they really could work.

Applying the ideas of Taylor resulted in the following consequences for the factory owners and

workers:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Higher output.

Standardisation.

Control and predictability.

The routine of the tasks allowed the replacement of skilled workers by non-skilled workers.

Thinking is for the managers, workers only work.

Optimisation of the tools for each worker (such as size and weight of the tools).

Taylor also analysed the work of foremen. Their jobs could be divided into subtasks and greater

efficiency could be reached if different foremen specialised only in one of the subtasks, such as

controlling the speed, inspecting the quality or allocating the work. Low-skilled, and thus cheaper,

workers could replace high-skilled workers through the use of more machinery and specialisation.

One of the most famous examples of a factory that successfully applied Taylor's principles was

the Ford Motor Company. Many managers tried to implement time studies and other elements of

1.2 A rational-system view of organisations

Taylor's system but refused to pay the higher wages that are also part of Taylor's system. The

Ford Motor Company doubled wages simultaneously with the implementation of assembly lines

and scientific management to compensate workers for the dull work — and as a way of creating

customers for the cars.' Henry Ford, the founder of the Ford Motor Company, changed the production of automobiles from custom-made to a product for the masses. The Ford T, only available

in black with no factory options at all, was the first car produced in great numbers for the enormous

segment of middle-income people for whom cars had so far been an unthinkable luxury. This model

was in production from 1908 until 1927 and 15 million Ford Ts were produced. This lower cost

could only be reached by highly efficient production based on standardised and interchangeable

parts (all pieces of the cars are the same for all cars), continuous flow (making use of an assembly

line), division of labour (each worker is specialised in one very particular task) and elimination of

unnecessary efforts (by applying motion studies).

Car manufacturers, as well as many other factories, are still working according to many of

Taylor's principles. The work on assembly lines in particular has hardly been changed. There is a

strong incentive to keep the assembly line moving as fast as possible. However, there is an increasing focus on quality and flexibility, so now both productivity and quality must coexist, leading to

even higher pressures on employees. Many workers resisted Taylor's methods because they feared

the harder work and their skills becoming obsolete. Skilled jobs were turned into non-skilled

ones that could be done by anyone. Hence, workers lost their value as skilled employees. They also

lost any decision-making power regarding their work. Taylor selected workers and foremen on the

basis of qualities other than their skills and ability to think about their job. He chose them on the

basis of their physical condition and their ability to learn and cope with the standard methods.

Although the workers regarded Taylor and his principles as a threat, in his way Taylor respected

them by paying them more when they followedhis methods and increased productivity. Nonetheless,

he mainly saw workers as people who could be perfectly conditioned and trained. The application

of Taylor's ideas in many factories led to resistance by the labour unions and even to a strike. On

21 August 1911, a special committee of the House of Representatives of the USA was assigned the

task of investigating shop floor systems, including Taylor's system. From these investigations grew

a general resistance towards Taylor's systems on grounds of inhumanity.

Taylor's systems were very useful in creating high levels of efficiency and productivity, not only

for labour workers but also for office workers and those in service industries. However, Taylor's

ideas have been misinterpreted and misused, giving him a bad (but unfair) reputation for pressurising workers by inhuman work methods and forcing them to work at speed to enrich management.

Nonetheless, Taylor did neglect some important organisational behaviour aspects, such as the

importance of job satisfaction (see Chapter 3), non-financial work incentives (see Chapter 6) and

the positive role of groups and teams (see Chapters 7 and 8). Taylor saw groupings of workers as the

basis of 'soldiering'. Furthermore, later critics have referred to the `deskilling' of jobs because the

systems and machinery replaced craftsmen's skills and destroyed work satisfaction. Deskilling was

especially prevalent in the Ford Motor Company's production systems, also called `Fordism'. Taylor

optimised productivity around existing tools and machinery but did not strive for maximum

replacement of skilled labour by machinery. It was a combination of Taylor's principle on specialisation by dividing the tasks and the use of new machinery (Fordism) that led to deskilling. Many

researchers in the organisational behaviour field have reacted to job deskilling, the alienation of the

workers from their work and the products they are making, and the negative human consequences

of scientific management.

However, a study of UK call centres teaches us that the principles of scientific management and

Frederick Taylor are still alive (see the activity).17

16•

CHAPTER 1 Foundations of organisational behaviour and research

Activity

Are Taylor's principles still alive?

Call centres are subject to tight control on call handling time with standardisation of the way

customers' queries are handled. However, this should not be generalised for all call centres.

Some focus on quantity and apply Taylor's principles to maximise the number of calls, while

others focus on quality and allow more flexibility in time and manner of call handling.

Nonetheless, most call centres are intensively monitoring their operators, even if this reduces

staff motivation.

Questions

1 Do you agree that tight control and intensive monitoring are necessary at work in general?

2 Do you agree that tight control and intensive monitoring are necessary in an environment

such as a call centre?

3 Will people work more if they are paid more?

4 What else other than pay do people work for?

Henri Fayol

Henri Fayol is of the same period as Taylor but was born and lived in France where he worked as an

engineer and manager in the mining industry. Fayol is known through his landmark work General

and Industrial Management in which he described the basic principles of management.' His management principles were proposed as general principles and based on rationality, in a similar way to

Taylor, who also took a fundamentally rational view on management. Fayol worked his whole

career, first as an engineer and later as a manager, in a mining company. His famous book summarised the lessons he learned during his work as manager in that company. The reason for its success

is that Fayol was the first to describe management as a separate profession and activity in companies, practically inventing the concept of management. This does not mean that companies had

no leaders, directors or managers previously, but management as a separate task (i.e. different

from military leadership, e.g. Sun Tzu's The Art o f War, or government rule, e.g. Niccole Machiavelli's

The Prince) was not studied separately until Fayol.

Henri Fayol made management visible by defining it and describing in a normative way what

managers should do. There are a number of general principles that managers should follow and

basic tasks that they should execute. Table 1.1 describes the five main management tasks identified

by Fayol.

To execute these five basic tasks of management well, 14 general management principles should

be obeyed. These are:

1 Division of labour.

2 Authority and responsibility.

3 Discipline.

4 Unity of command.

5 Unity of direction.

6 Subordination of individual interest to the general interest.

7 Fair remuneration of personnel.

1.2 A rational-system view of organisations

Table 1.1 The Five Basic Management Tasks According to Fayol

Planning

Organising

Leading

(commanding)

Co-ordinating

Controlling

Predicting and drawing up a course of action to meet the planned goals. To plan is

literally making written plans, for 10 years, one year, one month, one week, one day

and special plans. The 10-year, one-year and special plans are the most important and

form the general plan. The 10-year plan should be adapted slightly every year and

totally reviewed every five years

This consists of allocating the materials and organising the people. Most

organisations are very hierarchical but every employee and department can still take

some initiative. Nonetheless, authority, discipline and control are major forces in the

organisation. Fayol pays a lot of attention to the role of the Board of Directors,

which is the hardest to compose and has the important task of selecting the general

management

Giving directions and orders to employees. Commanding consists of influencing and

convincing others to make them accomplish the goals and plans. This involves not

only giving orders but also motivating people

Co-ordinating mainly refers to meetings with the departmental heads to harmonise

the different departments into one unit, working for the general interest of the

company. Liaison officers can help to tune radically different ideas and goals between

two departments

Controlling to what extent the goals were met and if everyone is following orders

rigorously. This should be carried out by an independent and competent employee

Source: Based on H. Fayol, Administration Industrielle et Gendrale (Paris: Dunol, 1916).

8 Centralisation.

9 Hierarchy.

10 Order.

11 Equity.

12 Stability of tenure of personnel.

13 Initiative by every employee.

14 Unity among the employees.

These principles clearly include some aspects that we would now consider part of organisation

theory, organisational behaviour and human resource management fields. Authority cannot work

without responsibility. Everyone needs to know his or her responsibilities and should be punished

or rewarded by his or her boss. Discipline includes sanctions when the rules are broken. Although

Fayol puts the stress on centralisation in the organisation, he recognises that we should not overreact but find an optimal balance between centralisation and decentralisation. The same goes for

hierarchy, which should not be too strict since it makes the organisation inflexible. Direct communication between two persons of the same hierarchical level but from different departments should

be possible with the permission of their two direct bosses. Fayol took a very mechanistic view of

management and a lot of what he considers management refers to organising and structuring

organisations. In Chapter 10, you will notice that the four basic elements of the organisation structure, namely a common goal, division of labour, co-ordination and hierarchy of authority, parallel

the managerial tasks of Fayol.

Fayol's major concern was the lack of management teaching, although management is the most

important task for directors. Lack of teaching had three causes. First, there was no management

theory or management science and, therefore, this could not be taught like other sciences. Second,

CHAPTER 1 Foundations of organisational behaviour and research

mathematics was considered for decades as the best and highest possible development for engineers who will run a company. Third, in France, the most highly regarded schools were the schools

that educated engineers (broadly speaking, this is still the case today). Accordingly, the smartest

students were stimulated to choose engineering studies and so would learn more mathematics

than writing and social skills. Specific knowledge, such as mathematics, is only one of the many

skills a director needs. Fayol identifies six important skills a good manager or director needs. These

are physical qualities, mental qualities, moral qualities, general education, specific education and

experience.

Fayol admired Taylor, although he disagreed with two very important aspects of Taylor's ideas.

Fayol did not totally separate thinking and acting. Every employee has some management tasks

and should be able to take initiatives within his or her area of responsibility and within the rules of

the company. Unity of command (i.e. one employee should only receive orders from one boss — see

Chapter 10) is a very important principle for Fayol but does not fit in with the principles of Taylor.

According to Taylor, there should be functional management instead of military management.

Functional management refers to the specialisation of managers and departmental heads in certain management fields, such as time study, planning, the way the task should be performed, and

so on. Fayol accepts the importance of this daily guidance of the workers by specialised managers

but this does not imply that unity of command disappears. This very normative approach in his

work is often criticised. Not all organisations need to be very hierarchical, tightly controlled and

mechanistically organised to be successful. In fact, applying such principles may even threaten the

success of the organisation.

Chester Barnard

Chester Barnard is less well known than the other authors mentioned in this overview but his

ideas are no less important. He found that previous organisation theories had underestimated the

variability of individual behaviour and its effects on organisational effectiveness.' Barnard was

the president of the New Jersey Bell Telephone Company and in 1938 published his ideas in

The Functions of the Executive.

Barnard builds his theory and ideas on some general principles of co-operative systems.

Co-operation involves individuals. He describes individuals as separate beings but not totally independent. They have individual behaviour and the power of choice but their freedom is bounded by

two kinds of limitations, biological and physical. An individual has only limited possibilities when

acting alone because of limited physical strength and the impact on his or her environment.

Co-operative action in a formal organisation is therefore needed. However, co-operation is not

obvious. There are several possible limitations to co-operative actions which Barnard categorises as

either a lack of efficiency or a lack of effectiveness (see also Chapter 11). Efficiency exists when

there is a contribution of resources for the use of material and for human effort in such a way that

co-operation can be maintained. If the reward for one's efforts is too small, one will resign from cooperation. Effectiveness exists, according to Barnard, when the (personal) goals of the co-operative

action are achieved. Barnard identifies three necessary elements for co-operative actions, namely

the willingness to co-operate, a common purpose and communication (see Table 1.2).2°

Furthermore, Barnard explains that every organisation consists of smaller, less formal groups

with their own goals. Management needs to align those goals with the overall organisational

goal. An informal organisation exists within formal organisations and formal organisations cannot

exist without the informal organisation. The informal organisation is more invisible and its

existence is too often denied. Barnard made a major contribution by including individual choice,

1.2 A rational-system view of organisations

Table 1,2 Necessary Co-operation Elements According to Barnard

Willingness to

co-operate

A common purpose

Communication

about actions

Specialisation

Incentives

Authority

Decision-making

The will to co-operate is often very low. There are a lot of organisations and in

only a few is people's willingness large enough to co-operate

Goals differ for each person but there has to be some consensus between the

individual and organisational goals

Communication should be interpreted very broadly; a signal can be enough but

the communication needs to be clear

Specialisation refers to the way things are done, which things are done, who to

contact, at what places and in what time period. Organisations should try to

find new ways of specialisation to make the work more efficient

Incentives are necessary to persuade people to join co-operative actions and to

reduce the burden of the work. There are many types of incentives, some are

objective and some are subjective (also see Chapter 6)

Authority is 'communication (to order) in a formal organisation by virtue of

which it is accepted by a contributor of the organisation for governing the

contributor's actions'. Authority does not work without the individual's will to

accept the orders, however

Decision-making is determining what has to be done in what way and can be

based on own initiatives or authority. The former should be limited.

Opportunism is the counterpart of decision-making. It is only a reaction

to the environment. For every action there are some limitations in the

environment. To perform the action the limiting factors must be removed,

but doing this leads to new limitations. Constantly eliminating the

limitations requires experience and experiment. See Chapter 13 on

decision-making

Source: Based on C. I. Barnard, The Functions of the Executive (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938).

power and informal groups into organisation theory. Managers do not only need to 'pull' the

formal organisation but have to manage also the informal aspects of the organisation (see also