Competence and

Responsibility

The Third European Conference of

The European Council for High Ability

held in Munich (Germany), October 11-14, 1992

Volume 2

Proceedings of the Conference

Edited by

Kurt A. Heller und Ernst A. Hany

Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

Seattle · Toronto · Göttingen · Bern

Foreword

V o l u m e 2 of "Competence and Responsibility" contains t h e Proceedings of t h e 3 r d European

Conference conducted by the European C o u n c i l for H i g h A b i l i t y ( E C H A ) , w h i c h was held i n

M u n i c h , G e r m a n y , i n October 1 9 9 2 . This conference was intended t o provide a state-of-the-art

overview of t h e E u r o p e a n research o n giftedness and creativity a n d of attempts t o provide

differential education t o the highly able. T h e organization of the symposia a n d workshops

allowed a substantial exchange of ideas and practical approaches f r o m b o t h sides of the former

" i r o n curtain", and encouraged discussions a n d mutual stimulation of E u r o p e a n scholars and

practitioners a n d individuals of other continents w h o shared t h e i r valuable experiences w i t h the

other participants of the conference.

A t the t i m e w h e n w e chose "Competence and Responsibility" for being the m o t t o of this

conference, w e w e r e n o t aware that the same w o r d s w e r e used by a c o m p a n y of chemical

industries i n their newspaper advertisments. T h i s is n o t t h e place t o discuss any subconscious

effects of advertisment campaigns; instead, w e w o u l d like t o p o i n t t o t h e fact that education,

politics, a n d industry are m o r e and m o r e t a k i n g a systems view o n global issues. If one speaks

of competence, this first assumes a set of tasks w h i c h requires the competence focused, and

second makes a c o m p a r i s o n between subjects of different levels of competence. T h e concept

of responsibility expands this perspective of interactive relationships b y referring t o global values

w h i c h are accepted by all partners w h o interact i n a system of competences and demands.

Based o n these premises, first the education of the gifted is conceptualized as a task every

society has t o fulfill i n order t o secure b o t h t h e individual's right of a p p r o p r i a t e education and

its o w n progress a n d second, this education has t o a i m at developing the gifted s attitude of

being responsible for their nurturing society's well-being, i . e. of being obliged t o a t t e m p t i n g t o

solve the urgent problems of their decade. T h e M u n i c h conference looked at this system of

mutual responsibility f r o m a psychological and educational perspective. T h e development of

y o u n g people's talents and adults' skills by means of education provided by family and school,

of psychological t r e a t m e n t , o r of the careful design of the w o r k e n v i r o n m e n t , a n d by means of

selecting individuals w h o fit best t o the learning and w o r k i n g settings available w e r e the topics

dealt w i t h i n most contributions.

M o r e t h a n 4 0 0 scholars and practitioners f r o m 3 1 different countries t h r o u g h o u t the w o r l d

( 9 0 % f r o m Europe, 5 % f r o m N o r t h America/Canada, 5 % f r o m the Asia-Pacific area) participated i n this conference. A p p r o x i m a t e l y 2 5 % of the over 2 0 0 contributions are incorporated

i n t o this b o o k . T h e abstracts of all 2 0 0 contributions are included i n v o l u m e 1 w h i c h was edited

by E. A . H a n y a n d K. A . Heller i n 1 9 9 2 , a n d published by H o g r e f e & H u b e r , Seattle (ISBN

3-8017-0684-2/ISBN 0-88937-111-3).

Unfortunately, w e w e r e n o t able t o include here m a n y other interesting papers due t o lack of

space and for financial reasons. I n addition t o volume 2 , a G e r m a n r e p o r t o n the w o r k s h o p

"Behinderung u n d Begabungsentfaltung" (Handicap and D e v e l o p m e n t of Giftedness) has been

published under the same title by the "Stiftung zur Förderung körperbehinderter Hochbegabter",

Vaduz/Liechtenstein (1993) - I S B N 3 - 9 0 8 - 5 0 6 - 0 7 - 7 ; see t h e last c o n t r i b u t i o n t o the section

6 (Special Groups) i n this volume.

T h e m a i n criteria i n realizing the necessary selection for volume 2 w e r e a truly European and

international representation of recent research topics i n the field of gifted education a n d - of

course - the quality of the contributions. Finally, w e intended t o focus n o t only research problems

a n d outcomes but also their applicability t o practice and policy. T h e editors t h a n k all contributors

for their confidence i n us and for (generally) submitting the manuscripts o n t i m e .

T h e content ranges f r o m o p e n i n g speeches t o keynote addresses (including commentaries),

symposia, w o r k s h o p s , audiovisual and poster presentations. T h e selected papers are classified

i n t o t h e following categories or subject areas:

VI

(1)

Opening

Speeches,

c o m p r i s i n g of a n official declaration of the Federal G o v e r n m e n t of

G e r m a n y concerning t h e i r politics of nurturing the gifted, and of t h e introductory p o s i t i o n

paper of t h e c h a i r m a n of the conference.

(2) Ability and Achievement,

focusing m a i n l y o n intraindividual differences of talents a n d

skills w h i c h provide t h e basis of differential education.

(3)

Creativity

and Innovation,

w i t h contributions mostly issuing recent theoretical developments either of cognitive or of organizational processes w h i c h constitute creative innovation.

(4)

Development

of Giftedness

and Talent, particularly f r o m a life-long perspective, w i t h

contributions using methodological approaches as different as case studies and long-term

longitudinal studies o n representative samples.

(5)

Gender Issues,

emphasizing empirically p r o v e n relationships between attitudinal a n d

motivational sex differences and thematically corresponding differences i n achievement.

(6)

Special Groups, t h e contributions of w h i c h demonstrate the regrettable fact that m a n y

talents are wasted by internal or external handicapping conditions.

(7)

Identification

and Psychological

Measurement

Problems,

c o m p r i s i n g of contributions

w h i c h reach f r o m basic overviews t o recent developments of n e w tests and procedures f o r

identification.

(8)

Gifted Education

and Program Evaluation,

focusing primarily o n comprehensive reviews

of educational models o r o n special methodological procedures of evaluation.

(9)

Teachers of the Gifted, describing characteristics of m o r e versus less experienced teachers

w h i c h are of substantial influence t o the education of t h e gifted.

(10) Policy and Advocacy

in Gifted Education,

j o i n i n g b o t h contributions w h i c h represent

the o p i n i o n s held by political institutions of G e r m a n y and papers w h i c h add a broader

national o r international perspective o n efforts of systematically nurturing t h e gifted.

In order t o complete t h e proof-reading and because some papers f r o m contributors w h o are

not native English speakers had t o be rewritten, w e had t o cope w i t h standardizing the English

as well as w i t h t i m e and budgetary problems. H e n c e w e are n o w pleased t o present t h e

Proceedings of the 3 r d E C H A Conference, 1 9 9 2 , for a greater audience. W e w a n t t o express

our thanks t o all colleagues and co-workers w h o assisted us i n t h e editing w o r k . H e i d i Röder,

Edeltraud Schauer, and M o n i k a Wersing t y p e d several manuscripts, C a t r i n H e r t e r and K e r s t i n

Osterrieder checked the file transfers o n t h e computers. Colleen S. B r o w d e r assisted i n t h e

translation i n t o English, a n d Beate Karbaumer re-drew most of the figures and gave m o s t

manuscripts their final layout.

Finally, our thanks go t o T h e Federal Ministry of Education and Science i n B o n n , a n d t h e

D o n o r Association for the P r o m o t i o n of Science i n G e r m a n y (Stifterverband für die Deutsche

Wissenschaft) t h r o u g h " B i l d u n g u n d Begabung e. V . " (Private Association "Education a n d

Talent") i n B o n n for their grants. This s u p p o r t enabled us t o publish volume 1 (Abstracts) a n d

volume 2 (Proceedings). A n d w e are grateful that the H o g r e f e & H u b e r Publishers m a d e it

possible t o publish this b o o k i n the tried and tested way. O u r h o p e is that the Proceedings w i l l

contribute t o the progress of gifted education i n Europe and a r o u n d the w o r l d .

M u n i c h , January, 1 9 9 4

Kurt A.

Heller

Ernst

Hany

A.

Table of Contents

Foreword

V

I. O P E N I N G S P E E C H E S

Γ

Federal support p r o g r a m s for gifted and talented y o u n g people i n Germany:

C o n c e p t s a n d initiatives

Rainer

Responsibility i n research o n h i g h ability

Kurt

3

Ortleb

A.

7

Heller

II. A B I L I T Y A N D A C H I E V E M E N T

13

Individual differences i n talent

15

Hansgeorg

Bartenwerfer

C o m m e n t a r y o n "Individual differences i n talent"

Edward

25

Necka

Report f r o m t h e s y m p o s i u m "Structures and processes i n intellectual

achievement"

Andrzej

27

Sekowski

T h e role of preferences of cognitive styles and intelligence i n different

kinds of achievement

Andrzej

34

Sekowski

Intelligence - creativity relationship: A r e creative m o t i v a t i o n and need for

achievement influencing it?

Katya

Strategy use and m e t a m e m o r y i n gifted and average p r i m a r y school children

Christoph

Recent trends i n creativity research and theory

K.

Dentici

68

Trifonova

81

Andreani

Subject's semantic orientation and creative t h i n k i n g

Maria

55

Necka

Logical and creative t h i n k i n g i n adolescents

Ornella

53~

Urban

Gifted people and novel tasks

Edward

46

Perleth

III. C R E A T I V I T Y A N D I N N O V A T I O N

Klaus

40

Stoycheva

94

VIII

Personal a n d situational determinants of innovation

Lutz

von

101

Rosenstiel

I n n o v a t i o n processes i n self-organizing and self-reproducing social systems

Helmut

106

Kasper

C o m m u n i c a t i o n rather t h a n inspiration and perspiration?

Heinz

112

Schüler

IV. D E V E L O P M E N T O F G I F T E D N E S S A N D T A L E N T

ΪΪ7~

D e v e l o p m e n t of h i g h ability

119

Brigitte

Rollett

D e v e l o p m e n t of giftedness i n a life-span perspective

J . Monks

Franz

and Christiane

136

Spiel

Giftedness f r o m early childhood t o early adolescence: A pilot study

Christiane

Spiel

and Ulrike

141

Sirsch

A follow-up study about creative t h i n k i n g abilities of students

Aysenur

147

Yontar

F r o m the every-day w o r l d and the musical w a y of life of highly talented y o u n g

instrumentalists

Hans

Günther

153

Bastian

Early educative influences o n later outcomes: T h e T e r m a n data revisited

Herbert

Sares,

J . Walberg,

Winifred

Guoxiong

E. Stariha,

Zhang,

Trudy

Eileen

Wallace,

P. Haller,

and Susie

F.

Timothy

164

A.

Zeiser

V. G E N D E R ISSUES

179"

A n asset o r a liability?

181

Janice

A.

Voices of gifted w o m e n

Leroux

T I P studies of gender differences i n talented adolescents

David

Goldstein

and Vicki B.

190

Stocking

Gender differences a m o n g talented adolescents

Linda

E. Brody,

Linda

B. Barnett,

and Carol

204

J.

Mills

VI. S P E C I A L G R O U P S

2 U

Gifted differently cultured underachievers i n Israel

213

Nava

Butler-Por

U n d e r f u n c t i o n i n g : T h e problems of dyslexics and their remediation

Diane

T h e problems of highly able children w i t h a n unbalanced intelligence structure

Maria

224

Montgomery

Herskovits

237

IX

Disability a n d t h e d e v e l o p m e n t of giftedness

Ernst

A.

247

Hany

VII. I D E N T I F I C A T I O N A N D P S Y C H O L O G I C A L

PROBLEMS

MEASUREMENT

Identification o f t h e gifted

Ivan

251

253

Koren

C o m m e n t a r y o n "Identification of the gifted"

Harald

270

Wagner

T h e w o r k s h o p "Identification of gifted students": Summarizing paper

Günter

Trost

and Ingemar

A multi-step selection process for the high-ability children

Nail $ahin

and Ekrem

274

Wedman

280

Duzen

Subskills o f spatial ability and their relationships t o success i n accelerated

m a t h e m a t i c s courses

Heinrich

286

Stumpf

T h e D A N T E Test

Hermann

298

Rüppell

Science Process Skills Tests and Logical T h i n k i n g Test for identifying t h e

scientifically gifted i n K o r e a

Seokee

302

Cho

Identification o f mathematically gifted students

Zuzana

310

Tomalkova

VIII. G I F T E D E D U C A T I O N A N D P R O G R A M E V A L U A T I O N

T h e p r o m o t i o n of h i g h ability and talent t h r o u g h education and instruction

Diane

317~

319

Montgomery

C o m m e n t a r y o n " T h e p r o m o t i o n of high ability and talent t h r o u g h education

and instruction"

Heinz

336

Neber

T h i n k i n g i n t h e head a n d i n the w o r l d

Joan

338

Freeman

Evaluating a n accelerated mathematics p r o g r a m : A centre of inquiry

approach

Michael

351

C. Pyryt

and Ron

Moroz

Evaluating p r o g r a m s for the gifted: Insights resulting f r o m a n international

workshop

Ernst

A.

355

Hany

χ

IX. T E A C H E R S O F T H E G I F T E D

360

C o m p a r i n g G T trained a n d G T untrained teachers

361

Jan

B. Hansen

and John

F.

Feldhusen

T h e "gifted c h i l d " stereotype a m o n g university students a n d elementary school

teachers

367

Nail $ahin

and Ekrem

Duzen

X . P O L I C Y A N D A D V O C A C Y IN G I F T E D E D U C A T I O N

377~

Education policy concept of t h e government of T h e Federal Republic of

G e r m a n y o n t h e p r o m o t i o n of giftedness

Ernst

August

T h e p r o m o t i o n of highly gifted pupils

Georg

A.

386

Pauly

Nurturance i n Bavaria

Eduard

389

Pütterich

S u p p o r t for gifted pupils i n Saxony

Hans

383

Knauss

Types of giftedness p r o m o t i o n i n Baden-Württemberg

Peter

379

Blanke

Wilhelm

392

Berenbruch

C o m m e n t a r y o n t h e s y m p o s i u m "Educational policy conceptions o n nurturing

h i g h giftedness"

A. Harry

Identification of gifted university students for scholarships i n G e r m a n y

Günter

407

Wilgosh

G r o w i n g u p gifted a n d talented i n T a i w a n

Wu-Tien

400

Trost

H i g h achievement a n d underachievement i n a cross-national context

Lorraine

397

Passow

412

Wu

I n f o r m a t i o n o n t h e T h i r d E C H A Conference

422

A u t h o r s ' addresses

423

I.

OPENING SPEECHES

Introduction

T h e T h i r d E u r o p e a n Conference of t h e European C o u n c i l for H i g h Ability was opened by a

triplet of lectures t w o of w h i c h are given o n t h e following pages. Rainer Ortleb, the G e r m a n

Federal Minister of Education and Science, t o o k t h e occasion of the conference for giving a n

official statement of t h e Federal G o v e r n m e n t ' s principles of support for gifted and talented

y o u n g people i n Germany. I n addition, he described current initiatives a n d p r o g r a m s of support

of t h e gifted w h i c h added t o the educational measures t a k e n b y the governments of the G e r m a n

federal states (Laender). Michael V o r b e c k f r o m t h e Council of Europe, Section of Educational

Research, illuminated t h e situation of the gifted by introducing a general E u r o p e a n perspective.

H e described measures t a k e n by t h e Council of Europe t o p r o m o t e research and education of

the gifted, and described his profile of the " h o m o europaeus" w h i c h should guide the educational

goals pursued by t h e schools of this continent. Vorbeck's contribution was n o t included i n this

volume as V o l u m e 1 of Competence a n d Responsibility contained a long draft of his speech.

K u r t Heller, c h a i r m a n of the E C H A conference, t h e n presented his observations of the

E u r o p e a n a n d international state of research o n giftedness, a n d described t h e major trends and

results of research and its practical applications. H e also p o i n t e d out that current efforts of

designing educational services for t h e gifted are i n need of further basic research and of

cross-cultural studies.

Federal support programs for gifted and talented

young people in Germany: Concepts and

initiatives

Rainer Ortleb

The Federal

Minister

of Education

and Science,

Bonn/Berlin,

Germany

M a d a m President, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I.

I a m delighted t o be able t o talk t o y o u , the participants i n the T h i r d European Conference

for H i g h A b i l i t y , here today. T h e a i m of the conference - that is t o say t o intensify and deepen

the discussion between giftedness researchers and experts o n education policy f r o m the

countries of Europe - is very close t o m y heart. I n this context, I also h o p e t o see a particularly

lively a n d fruitful exchange of ideas w i t h the numerous conference participants f r o m Eastern

Europe. A s the countries of Europe c o m e closer together, w e are going t o be faced by major

tasks - something that w e Germans are already very m u c h noticing i n our special situation.

Against a background of freedom, scientific c o m m u n i c a t i o n at the national and international

level w i l l increasingly contribute towards eliminating prejudices and obstacles, while providing

new food for t h o u g h t at the same t i m e .

Today, p r o m o t i o n of the gifted, p r o m o t i o n of t o p scientific achievements and t h e creation of

educational elites r a n k a m o n g the central questions i n the socio-political debate i n t h e Federal

Republic of G e r m a n y , and particularly i n the debate o n education policy.

Initiatives aimed at increased p r o m o t i o n of particularly gifted children, y o u n g people, trainees

and students are meeting w i t h g r o w i n g approval a m o n g politicians and the general public. T h e

Federal G o v e r n m e n t sees this as a n encouragement t o continue its c o m m i t m e n t t o the

p r o m o t i o n of special talents and gifts i n the non-school sector, i n vocational training and i n

higher education institutions.

II.

T h e policy of the Federal G o v e r n m e n t is geared t o greater differentiation between t h e forms

of education and the supplementary p r o m o t i o n measures available because it is convinced that

this is t h e only w a y of giving the necessary consideration t o t h e major differences i n talents and

inclinations and the wide variety of levels of performance. T h i s basic standpoint automatically

results i n a positive attitude towards p r o m o t i o n n o t only of t h e disadvantaged, but also of the

gifted. A differentiated range of education and training measures should be available, together

w i t h supplementary p r o m o t i o n schemes, so that every individual can develop his o r h e r range

of talents t o the full.

Particularly gifted people should primarily be p r o m o t e d for their o w n sake. T h e full developm e n t of their capabilities and performance potential is a prerequisite for development of their

personality as a w h o l e . I n addition, there is a g r o w i n g consensus of o p i n i o n that t h e Federal

Republic of Germany, like t h e other countries i n Europe, cannot afford only t o accept and

p r o m o t e special talents i n sports and individual artistic fields. W e need scientists and practicians

Rainer Ortleb

4

w h o develop n e w ideas, and managers w h o can successfully "sell" t h e m o n the w o r l d market.

T h e p r o m o t i o n of special gifts is necessary t o provide science, t h e e c o n o m y , political and

cultural life w i t h n e w stimuli resulting f r o m outstanding achievements of y o u n g talents.

III.

T h e Federal Republic of G e r m a n y is a federal state. Its constitution is geared t o preserving

and advancing t h e cultural independence and w e a l t h of traditions w h i c h have developed i n t h e

course of t h e centuries i n the G e r m a n Länder and t h e city states, such as Bavaria, Saxony and

H a m b u r g . W i t h this i n m i n d , dealing w i t h cultural affairs and t h e school system is t h e

responsibility a n d duty of t h e Länder.

W i t h i n t h e scope of its legislative powers, the Federal G o v e r n m e n t also has t o w o r k towards

the equality of t h e situation i n t h e education sector. I n this way, it contributes towards a h i g h

standard of education a n d training across t h e nation and safeguards occupational mobility. This

is particularly i m p o r t a n t w i t h a view t o t h e process of E u r o p e a n unification. T h e Federal

G o v e r n m e n t exercises these competences i n the field of higher education institutions, vocational

training, further education and individual fields of non-school p r o m o t i o n . T h e responsibility for

the p r o m o t i o n of gifted y o u n g people outside the school sector is derived f r o m its responsibility

for t h e p r o m o t i o n of junior scientists.

Even those w h o advocate t h e power-dividing function of o u r federal system a n d see our

opportunities as lying i n the variety of initiatives inherent i n this system, must p e r m i t the question

of h o w t h e responsibility of the Federal Government for the education policy of t h e n a t i o n as

a w h o l e can be strengthened and further consolidated.

I w o u l d particularly like t o stress this p o i n t against the background of t h e current debate o n

amending t h e Basic L a w . T h e restriction of the competences of t h e Federal G o v e r n m e n t i n the

education sector w o u l d lead t o a situation w h e r e it w o u l d n o longer be possible t o guarantee

the measure of quality and equality i n t h e education sector w h i c h all democratic parties have

demanded i n t h e past. T h e w a y i n w h i c h the p r o m o t i o n of t h e gifted has developed seems t o

m e t o be a particularly g o o d example.

IV.

T h e p r o m o t i o n of t h e gifted by the Federal G o v e r n m e n t covers all fields of education:

T h e r e can be n o doubt as t o t h e fact that it is t h e task of t h e school t o i m p a r t fundamental

qualifications. H o w e v e r , despite all their commendable efforts t o provide differentiated instruct i o n , t h e y are often n o t i n a p o s i t i o n t o give especially gifted pupils t h e a t t e n t i o n t h e y need.

Moreover, school is n o t the only place w h e r e particularly gifted y o u n g persons can be p r o m o t e d .

O n l y a n a p p r o a c h towards p r o m o t i o n of the gifted w h i c h is geared t o every element of their

personality holds t h e promise of lasting success. I n recent times, m o r e and m o r e emphasis has

been placed o n this aspect by giftedness researchers, for instance by Professor H a r r y Passow,

the Nestor of education for t h e highly gifted f r o m t h e U S A .

T h e out-of-school p r o m o t i o n schemes of the Federal G o v e r n m e n t for gifted y o u n g people of

school age essentially consist of three elements:

1. I n numerous research schemes a n d pilot projects, w e are p r o m o t i n g basic research a n d

t h e development of theories for the identification of special gifts a n d talents, partly w i t h the

a i m of building u p a soundly-based advisory system for pupils parents and teachers. Research

o n giftedness has i n t h e m e a n t i m e become one of the principles of practical teaching,

educational advice, careers advice a n d , above all, identification. A n u m b e r of i m p o r t a n t projects

w h i c h w e r e c o m p l e t e d only recently will be discussed i n detail as contributions t o t h e Conference

i n the next few days.

G e r m a n federal support p r o g r a m s for gifted a n d talented

5

2 . A n o t h e r key field of t h e p r o m o t i o n a l measures of the Federal G o v e r n m e n t i n the non-school

sector is national competitions.

T h e y have proved particularly successful as a n instrument for

p r o m o t i n g t h e gifted. Special m e n t i o n should be made of the national competitions i n t h e fields

of mathematics, chemistry, physics, i n f o r m a t i o n technology, m o d e r n languages and history.

These c o m p e t i t i o n s place special demands o n analytical talent and creativity. T h e y are a n

invitation t o y o u n g , highly gifted people t o develop their special skills and t r y t h e m out i n fair

c o m p e t i t i o n . T h e r e has been a very satisfying response t o this offer a m o n g school pupils i n the

n e w Länder. T h e y o u n g people take p a r t i n almost all the competitions i n numbers correspondi n g t o their p r o p o r t i o n of their contemporaries. There has even been a n above-average

response t o some of the most i m p o r t a n t competitions, such as that i n mathematics o r the

' Y o u n g Researchers" (Jugend Forscht) c o m p e t i t i o n .

T h e national w i n n e r s are sent t o t h e International Scientific Olympics i n mathematics,

chemistry, physics, i n f o r m a t i o n technology a n d biology w h e r e , I a m pleased t o say, t h e G e r m a n

teams regularly achieve impressive successes. Cultural and artistic competitions supplement the

range of opportunities offered t o y o u n g people.

H o w e v e r , the goal of p r o m o t i n g special talents and gifts by w a y of competitions w o u l d n o t

be achieved if this p r o m o t i o n ended w i t h the award of the prizes.

3 . F o r this purpose, t h e Federal Ministry of Education and Science has, since 1 9 8 8 , tested

extracurricular S u m m e r courses i n the f o r m of a pupils'

academy

as another element of

p r o m o t i o n of the highly gifted. Selected o n t h e basis of very stringent criteria, y o u n g people

between t h e ages of 1 6 and 1 8 live together for several weeks i n selected, somewhat

out-of-the-way places, such as boarding schools, and are instructed - i n special fields chosen by

themselves - by university professors, recognised artists and leading economic experts. These

pilot projects have been very successful. Therefore, there are plans t o establish academies of

this k i n d for about 1,500 y o u n g people per year o n a p e r m a n e n t basis.

V.

W h i l e the p r o m o t i o n of special talents i n the higher education sector already has a long-standing t r a d i t i o n , and t h e p r o m o t i o n of gifted pupils i n and out of school has become increasingly

i m p o r t a n t i n recent years, t h e p r o m o t i o n of special gifts and talents i n vocational

training was

n o t a central element of education policy u p t o t h e early Nineties. T o d a y , some two-thirds of

all y o u n g people i n G e r m a n y are prepared for w o r k i n g life i n a system of vocational training

i n companies. U p t o n o w , they had n o access t o p r o m o t i o n schemes for the gifted. I considered

it a challenge t o change t h e situation.

W e have succeeded i n m a t c h i n g the p r o m o t i o n of the gifted i n schools and higher education

institutions w i t h a corresponding system of p r o m o t i o n i n vocational training because there, t o o ,

there are y o u n g people w h o are willing and able t o reach above-average achievements i n their

occupation.

A craftsman w h o does top-class w o r k i n his field belongs just as m u c h t o a small elite as a

university professor. A l t h o u g h particular gifts of y o u n g specialists i n companies, practices and

administrative authorities manifest themselves i n a different w a y t h a n i n scientific or artistic

w o r k , for example, this does n o t m e a n that they are any less deserving of p r o m o t i o n . T h a t is

w h y I launched the p r o g r a m m e entitled " P r o m o t i o n of the Gifted i n Vocational T r a i n i n g " i n the

S u m m e r of 1 9 9 1 . T h e opportunities for p r o m o t i o n w h i c h it provides are designed t o help

y o u n g people t o develop their practical, intellectual, social and creative capacities t o the full i n

their w o r k .

A t the same t i m e , the " P r o m o t i o n of t h e Gifted i n Vocational T r a i n i n g " is a n indication of the

Federal G o v e r n m e n t ' s will gradually t o p u t vocational training o n a n equal footing w i t h schooling

and higher education. Perhaps this will fulfil t h e h o p e that, m o r e t h a n has previously been the

Rainer Ortleb

6

case, a greater n u m b e r of gifted y o u n g people w i t h a w i l l t o w o r k will see vocational training

a n d staying i n their occupation as a w o r t h w h i l e alternative t o studying. Particularly against the

backdrop of E u r o p e a n unification a n d the efforts t o harmonise economic and social standards

i n t h e unified G e r m a n y , w e need a strong e c o n o m y i n b o t h the old and t h e new G e r m a n Länder.

In this context, w e are reliant n o t o n l y o n t h e abilities of entrepreneurs a n d managers, but also

and i n particular o n the performance of highly qualified specialists i n companies.

T h e participants i n t h e p r o g r a m m e " P r o m o t i o n of t h e Gifted i n Vocational T r a i n i n g " can

receive grants for u p t o four years t o finance further education activities r u n n i n g parallel t o their

w o r k . These grants can be used, for example, for learning foreign languages, for periods abroad

o r for t h e acquisition of knowledge and skills i n related fields of t r a i n i n g .

T h e scheme for p r o m o t i o n a l vocational t r a i n i n g w i l l be fully established by the end of 1 9 9 3 ,

after w h i c h t i m e some 9 , 0 0 0 y o u n g employees per year w i l l be able t o enjoy t h e benefits of

special p r o m o t i o n .

VI.

T h e situation i n the higher education

sector ist different t o that i n school education and

vocational t r a i n i n g . T h e r e , the p r o m o t i o n of the gifted is traditionally a task of t h e lecturers, i n

particular. T h e y can recognise special scientific talents at a n early stage and have the o p p o r t u n i t y

t o giving t h e m specific scientific p r o m o t i o n .

T h e p r o m o t i o n of the gifted i n higher education institutions is also a task laid d o w n i n the

statutes of various private foundations and associations. A t the m o m e n t , there are nine

independent foundations dedicated t o the p r o m o t i o n of t h e talented i n the higher education

sector. I n addition, t h e L a n d of Bavaria has its o w n scheme for p r o m o t i o n of the gifted, although

it is limited t o Bavaria, and there are also numerous other foundations. A l l t h e schemes and

foundations for t h e p r o m o t i o n of the gifted expect outstanding achievements i n studies and

scientific w o r k . A b o v e a n d beyond these intellectual requirements, these institutions lay varying

degrees of emphasis o n other aspects, such as development of personality, readiness t o accept

responsibility and c o m m i t m e n t t o the state and society, as well as artistic and practical skills.

T h e y offer intensive scientific a n d individual support, as well as material assistance i n the f o r m

of scholarships.

A m o n g t h e numerous forms of p r o m o t i o n opportunities after completing a course of higher

education, special m e n t i o n should be m a d e of t h e p r o m o t i o n of doctoral candidates by the

institutions for the p r o m o t i o n of the gifted and t h e p r o m o t i o n of graduates by t h e Länder, as

well as t h e post-graduate colleges w h i c h are currently being set u p .

VII.

Ladies a n d Gentlemen, the T h i r d E u r o p e a n Conference o n H i g h Ability i n M u n i c h will trigger

initiatives, continue the exchange of ideas and experience i n this field and constitute a n

i m p o r t a n t basis for w o r k i n the c o m i n g years. In addition, I h o p e that the intensive discussion

of ways of p r o m o t i n g special gifts and talents will meet w i t h a great response n o t only a m o n g

the y o u n g people involved, their parents a n d their teachers, but also i n the public and the media.

I w i s h your Conference every success.

Responsibility in research on high ability

Kurt A . Heller

Institute

of Educational

Psychology,

University

of Munich,

Munich,

Germany

T h e title of this keynote can be interpreted i n several ways. I c a n only emphasize a few here.

(1) Contributions

in the identification

from research on giftedness to the improvement

of practical

and nurturance

of gifted children and

adolescents.

requisites

F r o m a n educational psychological p o i n t o f view, the role of nurturance of t h e gifted is

p r i m a r i l y individual

development

support. This implies at least t h e following: a) "Giftedness"

as a multifactorial concept, b) personality development is a n interactive process, c) nurturance

of t h e gifted as a function of o p t i m i z i n g individual (personality) and social developmental aspects.

This is tangential t o the social a n d educational policy of equal o p p o r t u n i t y .

On a): Independent of w h e t h e r "giftedness" is considered psychometrically as a predisposition

t o w a r d outstanding achievements i n various areas or cognitively as m o r e o r less domain-specific

expertise, n e w theories favor multidimensional models of giftedness (cf. Gardner, 1 9 8 5 ; Heller,

1 9 8 6 ; H a n y & Heller, 1 9 9 1 ; M o n k s , 1 9 9 2 ) . Theory-guided diagnostic and nurturance concepts

thus call for differentiated approaches w h i c h are n o t represented by one-sided IQ-fixings or

so-called cut-off models (Monks & Heller, 1 9 9 4 ) . T h e practical identification of gifted children

and adolescents frequently limps behind the state of t h e art recognitions f r o m research o n the

gifted.

O n b j : Giftedness first manifests itself as a relatively non-specific individual achievement

potential w h o s e development interacts w i t h the social learning e n v i r o n m e n t f r o m t h e very

beginning. T h i s indicates interaction w i t h educational and socialization variables. T h i s interact i o n process should be viewed as a mutual influencing of children's behaviors a n d parental

u p b r i n g i n g practices. T h e hereditary background is t h e n i m p o r t a n t i n t h e development of

giftedness mostly for t h e individual selection and e m p l o y m e n t of t h e learning opportunities

presented by t h e social e n v i r o n m e n t (cf. Scarr & McCartney, 1 9 8 3 ; W e i n e r t , 1 9 9 2 ) . Early

indicators of giftedness even suggest that during the first few m o n t h a n d years of life particular

activities develop w h i c h are expressed i n curiosity and exploratory behaviors. These can be

interpreted as influencing the socialization agents. A t t e m p t s t o provoke socialization conditions

adequate for giftedness and thus t o actively influence the learning e n v i r o n m e n t t o satisfy basic

cognitive a n d social-emotional needs are apparently characteristic of t h e behavior of very gifted

children (cf. Friedrich & L e h w a l d , 1 9 9 2 ) . A n i m p o r t a n t educational task for parents and

teachers o r other relevant socialization agents stems f r o m this. T h e d e m a n d for early identification a n d nurturance of gifted children and adolescents is thus founded o n t h e responsibility

for p r o v i d i n g a p p r o p r i a t e learning environments.

O n c): T h e constitution of the Federal Republic of G e r m a n y and that of most t h e individual

states guarantees t h e individual's right t o equal o p p o r t u n i t y . This is frequently - k n o w i n g l y or

unintentionally - incorrectly interpreted and used as a n argument against educational programs

for t h e gifted by its critics.

" W i t h a view t o t h e d e m a n d for equality of educational o p p o r t u n i t y a ... dual nuancing of the

equality t e r m is necessary. O n the one h a n d , equality i n t h e sense of Article 3 of t h e constitution,

means that every y o u n g person must have all educational paths o p e n . T h e r e is n o objective

K u r t Α . Heller

8

reason (e. g. race, religion, social status, sex) for excepting someone f r o m a particular

educational p a t h . O n the o t h e r h a n d , t h e social state clause of the constitution (Art. 2 0 ,

p a r a g r a p h 1 i n c o n n e c t i o n w i t h A r t . 2 , p a r a g r a p h 1 and A r t . 3) states that a dynamic c o m p o n e n t

is contained i n the t e r m of equality, such that each individual's o w n situation should be

considered" (cited according t o Gauger, 1 9 9 2 , p . 25).

T h e individual's right t o equal education opportunities thus stands face t o face w i t h t h e social

responsibility for offering a n adequate spectrum of specific programs. T h e degree t o w h i c h the

individual y o u t h takes advantage of these offerings cannot be determined by t h e state, but is

determined by individual interests, abilities, educational goals, etc. This is n o t t o say t h a t the

state should n o t insist o n a n obligatory basic education for everyone. Therefore, t h e decision

for m a k i n g use of educational opportunities lies w i t h the individual him-/herself. I n a d d i t i o n ,

there are m a n y instances w h e r e personality development is interfered w i t h t h r o u g h less

adequate socialization conditions, deficient learning environments o r individual handicaps. T h e

school's task here and possible educational psychological counseling is t o m a x i m i z e the

educational equality. T h i s obligation results f r o m the equality rights principle w h e r e b y t h e social

c o m p o n e n t s of equal o p p o r t u n i t y should be discussed. T h i s includes all y o u t h , t h e gifted and

n o t only those w i t h learning a n d physical disabilities.

T h e realization of t h e constitutional r i g h t t o equal o p p o r t u n i t y , i . e. the t r a n s f o r m a t i o n of

needs i n t o educational activities, includes questions central t o applied research i n giftedness. In

addition t o learning a n d ability psychological aspects, gifted diagnostical, instructional psycho­

logical, educational and social psychological or support-didactical problems are relevant.

(2) Research on giftedness

necessitates

basis scientific

includes

research

not only technological

approaches.

or practical

questions,

but

also

Scientific history has often s h o w n the efficiency of applied research is greatly influenced by

basic theoretical and experimental research. T h i s basis rule also holds true for research o n

giftedness and for t h e practice of nurturing the gifted, including diagnosis, counseling, and

intervention. O n e could n a m e , for example, innovative approaches f r o m m o r e recent cognitive

psychology or expertise research i n t h e expert-novice paradigm (for current i n f o r m a t i o n , see

also Gruber & M a n d l , 1 9 9 2 ; Schneider, 1 9 9 2 , 1 9 9 3 ; Shore & Kanewski, 1 9 9 3 ; Perleth er

al., 1 9 9 3 o r contributions f r o m C h o , Freeman, and/or Sekowski, i n this volume). T h i s p r o d u c e d

i m p o r t a n t drives w i t h i n applied research o n p r o b l e m solving as w e l l as i n instructional questions,

such as w e find i n research o n learning a n d t h o u g h t processes specific t o the gifted, m e m o r y

strategies, metacognitive competencies, c o p i n g styles, etc.

A d d i t i o n a l topics, m o r e related to basic scientific questions are based o n longitudinal analyses

(e. g. description a n d explanation) of development processes i n the gifted. T h i s includes

social-cultural contexts w h i c h p r o m o t e or inhibit development (cf. M o n k s & Spiel, this volume).

In a d d i t i o n , (semi-)experimental studies w i t h the function of causal analyses, for e x a m p l e , for

explaining of sex differences i n various dimensions of giftedness (competence) a n d / o r achieve­

m e n t areas (performance), especially i n m a t h , sciences, and technology (cf. B r o d y a n d Goldstein

& Stocking, this volume). Scientific recognitions contribute n o t only to answering general or

differential psychological questions. T h e explanatory knowledge acquired leads t o t h e devel­

o p m e n t of the knowledge for changes necessary i n practical nurturance of the gifted, e. g. i n

counseling and intervention, i n education a n d instruction.

(3) important

advances in knowledge

about developmental

conditions

and adolescents

can also be expected from cross-cultural

socialization

thus far been somewhat

neglected

in the research of the gifted, despite

advantages.

of gifted

children

research. This has

its

methodological

T h e reason for relatively few cross-cultural studies that can be referred t o as m o r e t h a n

international cooperations but meet scientific methodology requirements is t h e e n o r m o u s cost

9

Responsibility i n research o n h i g h ability

but also specific methological problems w h i c h frequently confound t h e w o r k and financial load.

I w i l l r e p o r t m o r e o n this later. O n e expects cross-cultural

research approaches w i t h i n

giftedness t o b r i n g about a n increase i n knowledge with regard t o various cultural influences o n

individual developmental and educational processes (cf. Eckensberger & Krewer, 1 9 9 0 ) . This

goal should be m e t by a specific research strategy. This means that cross-cultural psychology

should be defined by research methods and n o t by the object research (Petzold, 1 9 9 2 ) . Three

types of c o m p a r i s o n are relevant: a) cross-national, b) cross-cultural, a n d c) cross-societal. In

the context of o u r research p r o b l e m , the second, cross-cultural studies are of interest; w i t h

regard t o t h e cross-national view cf. Wilgosh (this volume). Culturally caused behavioral

differences i n individual development should be indentified t h r o u g h t h e systematic c o m p a r i s o n

of psychology variables or results obtained in different cultural conditions. Equivalent or

non-cultural measurement instruments must be employed. This is a major p r o b l e m of cross-cultural research. O n the basis of such research designs, universality assumptions c a n be examined

i n relevant development, educational, learning or instructional areas. This is a function of

cross-cultural psychology w h i c h was already emphasized by W i l h e l m W u n d t i n his psychology

of different cultures at the t u r n of the century. Thus, the so-called etic (from phonetic) a p p r o a c h

starts w i t h a universality hypothesis of h u m a n behavior. In contrast, t h e so-called emic (from

phonemic) a p p r o a c h looks at cultural socialization influences w i t h i n certain cultures (culturalrelativity hypothesis). Accordingly cultural-specific and valid measurement w h i c h must also be

culture free instruments make it difficult t o actual make cultural comparisons. Therefore, newer

ecopsychological models (e. g. Berry, 1980) attempts t o integrate concepts f r o m "emic" and

"etic" (cf. Petzold, 1 9 9 2 , p. 3 1 I f . ) .

Cross-cultural studies can provide new recognitions about social-cultural development and

nurturance conditions of the gifted solely f r o m their change perspective. T h i s could lead t o

greater variety i n t h e support p r o g r a m ideas. Not only a practical use but also tolerance t o w a r d

foreign cultures is increased (cf. Butler-Por, this volume). T h e meeting of international ideas

a n d cultures can also be supported by international conferences such as this E C H A conference.

A l t h o u g h t h e exchange of i n f o r m a t i o n and ideas is central here, the i n f o r m a l contacts should

n o t be dismissed i n their peace m a k i n g role. If the participants of E C H A feel reached b y this

statement, t h e n a n i m p o r t a n t goal of E C H A has been achieved.

Before I g o o n t o a comparative overview of the contents of the p r o g r a m , one last research

policy responsibility should be mentioned.

(4) As long as research is supported

by state or private/public

foundations

and is directly

or indirectly

a public service, a mutual responsibility

grows between the society and the

research

community.

W i t h o u t w a n t i n g t o question the freedom of research - i . e . t h e responsible selection of topics

and methods by t h e researchers themselves - the simultaneous responsibility of the society

t o w a r d society by the direct or indirect funding of research must be emphasized. T h i s stipulation

also holds true for t h e research of giftedness, which otherwise is i n danger of isolation (and n o t

o n l y f r o m t h e mainstream of the scientific community). O n the other h a n d , qualified researchers

i n this field have t h e same rights as other sicentists, to demand a p p r o p r i a t e w o r k conditions

where one can consider scientifically desirable questions f r o m the field of basic research and

also f r o m t h e practice of giftedness nurturance. It can be taken as a positive sign that the

scientific a n d public o p i n i o n about the uses and rights of research o n giftedness is playing a n

increasing role - albeit small i n comparison w i t h other topics - i n t h e consciousness of those

responsible. Perhaps this international conference in Europe can increase t h e initiative here

a n d elsewhere - for t h e g o o d of the c o m i n g generation and t o i m p r o v e t h e future of all m a n k i n d .

(5) A content

analysis

with the previous

nine

of the topics here at the third ECHA

WCGT

world conference

proceedings

conference

in

and the most

comparison

important

10

Journals in the field of giftedness

research points to important

trends

research scene. This could be important

for the continual

development

gifted at the European

level.

K u r t Α . Heller

in the

international

of research on the

First, here are analysis results f r o m the conference proceedings of t h e previous nine w o r l d

conferences of t h e W o r l d Conference for Gifted and Talented C h i l d r e n (WCGT). A total of 4 0 8

conference presentations have been published f r o m 1 9 7 5 t o 1 9 9 2 . T h i s corresponds t o a

publication percentage of about 1 5 % . A p p r o x i m a t e l y 4 0 % w e r e f r o m practice, 2 0 % each i n

t h e areas of theoretical and empirical reports (on applied research), 1 5 % o n gifted programs

and s u p p o r t of the gifted. O n l y 5 % (in the last three years) discussed t h e t o p i c of basis research

(Heller & Menacher, 1 9 9 2 ) . T h i s picture reflects t h e analyses of relevant journals (Pyryt, 1 9 8 8 ;

Rogers, 1 9 8 9 ; Carter & Swanson, 1 9 9 0 ) . H e r e , t o o , t h e majority of the practice-oriented

applied research is e m p l o y i n g generally simple statistical methods. O n l y about 2 5 % of the

studies r e p o r t e d can be considered as hypothesis oriented. M o r e demanding statistical methods

such as p a t h analyses o r cluster analyses are rarely f o u n d here and are probably published i n

journals (cf. Pyryt, 1 9 8 8 ) .

T h e need t o catch u p i n theoretically guided experimental and quasi-experimental research

o n giftedness is emphasized indirectly i n the classification of psychological subdisciplines taking

part. T h e percentage of general psychologists t a k i n g part is negligible (median of about 5%),

whereas educational psychologists make u p about 7 0 % and clearly dominate.

A m o r e recent content analysis (Heller, 1 9 9 3 ) of (English-language) journals w i t h the majority

of publications o n t h e gifted f r o m t h e last 1 0 years (Gifted C h i l d Quarterly, Roeper Review,

J o u r n a l for the Education of the Gifted, and Gifted Education International) provided the

following picture: T h e topics "Gifted Education" and "Programs and N u r t u r i n g " are most strongly

represented i n all four journals analyzed w i t h percentages between 3 0 and 6 0 . T o p i c s such as

"Characteristics of t h e Gifted and Talented" are m o r e frequently found i n the J o u r n a l for the

Education of t h e Gifted (39%) and i n t h e Gifted C h i l d Quarterly (28%) versus the Roeper Review

(21.5%) a n d Gifted Education International (19%). "Social C o n t e x t " has its strongest repre­

sentation i n the Gifted C h i l d Quarterly w i t h 1 3 % , "Identification" w i t h 7 . 5 % each i n the Gifted

Child Quarterly and the J o u r n a l for the Education of the Gifted. T h e rates of " L e a r n i n g und

P e r c e p t i o n " and "Development" are astonishingly l o w i n all four journals. Solely the category

"Definitions a n d Concepts of Giftedness and Talent" had higher percentages i n t h e Gifted Child

Quarterly (27%) and the J o u r n a l for t h e Education of the Gifted (16%). These results generally

c o n f i r m those reported by Rogers ( 1 9 8 9 ) and Carter a n d Swanson ( 1 9 9 0 ) w h o , i n part, included

different journals.

W h a t picture is presented by the contributions t o the T h i r d E C H A conference? Ninety percent

of the 4 0 0 conference participants c o m e f r o m Europe and 1 0 % f r o m overseas. O f the

non-Europeans, 5 % are f r o m N o r t h A m e r i c a and Canada and 5 % f r o m Asia. Africa, Australia

and N e w Zealand are n o t represented. T h e G e r m a n participants are, as expected, t h e leading

g r o u p w i t h 3 5 % . A considerable number of visitors c o m e f r o m the former c o m m u n i s t states of

Europe. T o g e t h e r t h e y make u p nearly a t h i r d . Following G e r m a n y (35%), H u n g a r y , Poland

and the CSFR are represented w i t h 9 % . T h e former states of the U S S R follow w i t h 7 % . W i t h

that t h e T h i r d E C H A Conference contributes significantly t o the European U n i f i c a t i o n . T h e

changes w h i c h w e r e already b e c o m i n g apparent t w o years ago at t h e Second E C H A C o n ­

ference ( 1 9 9 0 ) i n Budapest seem t o continue i n a positive m a n n e r despite current conflicts

w i t h i n Europe. C o n c e r n i n g this our conference has already passed the first hurdle. T h e m a i n

topics of this conference and those of the preceeding w o r l d congresses o n h i g h ability are

relatively similar. T h e question of identification, however, w i t h 1 4 % , ist dealt w i t h twice as

frequently as at the other nine w o r l d congresses (with a n average of 7%).

11

Responsibility i n research o n h i g h ability

T h e r e is a lack of support and practical experience concerning the education of the gifted

including i n f o r m a t i o n about giftedness i n f o r m e r c o m m u n i s t states of Europe. W i t h regard t o

definition problems and theoretical bases of support for t h e gifted there is a g r o w i n g interest.

In contrast t o this, i n Western Europe there is a d o m i n a n t tendency t o establish private and

political initiatives for support programs for the gifted. This m i g h t be a positive sign. O r does

a l o w percentage (2%) of future oriented topics at this conference m e a n that it is necessary t o

be sceptical concerning t h e p l a n n i n g concepts? I h o p e n o t . W i t h regard t o actual analysis results,

w e k n o w that scientific disciplines a n d subdisciplines of psychology a n d education are c o n f i r m e d . T h e vast area of research i n t o h i g h ability seems t o be d o m i n a t e d b y educational

psychology a n d related subjects. A s a n educational psychologist, I do n o t regret this although

a higher scale of interdisciplinary w o r k could exert a positive influence. T h i s demand also

concerns t h e relationship between practical and basis research. "Pragmatic nuture and educat i o n of t h e gifted o n a n unsure scientific basis" - t o e m p l o y Franz Weinert's sober description

(Waldmann & W e i n e r t , 1 9 9 0 , p . 184) - will provoke further discussions.

References

Berry, J . W. (1980). Ecological analyses for cross-cultural psychology. In N. Warren (Ed.), Studies in

Cross-Cultural

Psychology, Vol. 2 (pp. 157-189). New York: Academic Press.

Carter, K. R., & Swanson, H . L. (1990). A n Analysis of the Most Frequently Cited Gifted Journal Articles

Since the Marland Report: Implications for Researchers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 34, 116-123.

Eckensberger, L. H . , & Krewer, B. (1990). Kulturvergleich und Ökopsychologie. In L. Kruse, C. F.

Graurnarm, & E.-D. Lantermann (Eds.), Ökologische Psychologie (pp. 66-75). München: Psychologie Verlags Union.

Friedrich, G., & Lehwald, G. (1992). Frühindikatoren geistiger Emtwicklung i m sprachlichen Bereich.

In E. A. Hany & H . Nickel (Eds.), Begabung und Hochbegabung (pp. 77-93). Bern: Huber.

Gardner, H . (1985). Frames of mind. The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gauger, J.-D. (Ed.). (1992). Vorträge und Beiträge der Politischen Akademie der KonradAdenauerStiftung, Heft 22. Bonn: Köllen.

Gruber, H . , & Mandl, H . (1992). Begabung und Expertise. In Ε. A. Hany & H . Nickel (Hrsg.), Begabung

und Hochbegabung

(pp. 59-73). Bern: Huber.

Hany, Ε. Α., & Heller, Κ. A. (1991). Gegenwärtiger Stand der Hochbegabungsforschung.

Zeitschrift

für Entwicklungspsychologie

und Pädagogische Psychologie, 28, 241-249.

Hany, Ε. Α., & Nickel, H . (1992). Positionen und Probleme der Begabungsforschung. In Ε. A. Hany &

H . Nickel (Eds.), Begabung und Hochbegabung (pp. 1-14). Bern: Huber.

Heller, Κ. A. (1986). Psychologische Probleme der Hochbegabungsforschung. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie

und Pädagogische Psychologie, 18, 3 3 5 - 3 6 1 .

Heiler, Κ. Α., & Menacher, P. (1992). State of the A r t of Research on Giftedness and Talent in the

Proceedings of the WCGT Conferences since 1975. In F. J . Monks & W. A. M. Peters (Eds.), Talent

for the Future: Social and Personality Development

of Gifted Children (pp. 138-148). Assen:

Van Gorcum.

Heller, K. A. (1993). International Trends and Issues of Research on Giftedness. In W. T. Wu, C. C.

Kuo, & J . Steeves (Eds.), Proceedings of the Second Asian Conference on Giftedness:

Growing

up gifted and talented (pp. 93-110). Taipai, Taiwan: NTNU.

Mönks, F. J . (1992). Ein interakrionales Modell der Hochbegabung. In Ε. A. Hany & Η. Nickel (Eds.),

Begabung und Hochbegabung

(pp. 17-22). Bern: Huber.

Mönks, F. J . , & Heller, Κ. A. (1994). Identification and Prc^ramming. In M. C. Wang (Ed.), Education

of Children with Special Needs. International Encyclopedia of Education, Vol. 5 (2nd ed., pp.

2725-2732). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Perleth, C., & Schauer, S. (1992). Content Analysis of the Papers of the 3rd ECHA Conference. ECHA

Conference Newsletter, no. 1, October 1 1 , 1992.

Perleth, C , Lehwald, G., & Browder, C. S. (1993). Indicators of high ability i n young children. In K.

A. Heller, F. J . Mönks, & A. H . Passow (Eds.), International

Handbook of Research

and

Development

of Giftedness and Talent (pp. 283-310). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

12

K u r t Α . Heller

Petzold, Μ. (1992). Kulturvergleichende Sozialisationsforschung. Psychologie in Erziehung und Un­

terricht, 39, 301-314.

Pyryt, M . C. (1986). The Gifted Child Quarterly As Database. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting

of the National Association for Gifted Children in Orlando, FL, Nov. 1988.

Rogers, Κ. B. (1989). A Content Analysis of the Literature o n Giftedness. Journal for the Education

of the Gifted, 13, 78-88.

Scarr, S., & McCartney, K. (1983). H o w people make their own environments: A theory of genotypeenvironment effect. Child Development,

54, 424-435.

Schneider, W. (1992). Erwerb von Expertise: Zur Relevanz kognitiver und nichtkognitiver Vorausset­

zungen. In Ε. A. Hany & H . Nickel (Eds.), Begabung und Hochbegabung (pp. 105-122). Bern:

Huber.

Schneider, W. (1993). Acquiring expertise: determinants of exceptional performance. In K. A. Heller,

F. J . Mönks, & A. H . Passow (Eds.), International Handbook of Research and Development

of

Giftedness and Talent (pp. 311-324). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Shore, B. M., & Kanevsky, L.S. (1993). Thinking processes: being and becoming gifted. In K. A. Heller,

F. J . Mönks, & A. H . Passow (Eds.), International Handbook of Research and Development

of

Giftedness and Talent (pp. 133-147). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Waldmann, Μ., & Weinert, F. Ε. (1980), Intelligenz und Denken. Perspektiven der Hochbegabungs­

forschung. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Weinert, F. E. (1992). Wird man zum Hochbegabten geboren, entwickelt man sich dahin oder wird man

dazu gemacht? In Ε. A. Hany & H . Nickel (Eds.), Begabung und Hochbegabung (pp. 197-203).

Bern: Huber.

II.

ABILITY A N D ACHIEVEMENT

Introduction

I n contrast t o average or below average performances, exceptional performances at school

or w o r k are usually contributed t o interindividual (cognitive and motivational) differences. This

overlooks, however, a n i m p o r t a n t moderator function i n social learning conditions. Hansgeorg

Bartenwerfer first discusses i n m o r e detail such interindividual differences w h i c h have been

p r o v e n t o be individual

prerequisites for e m i n e n t performance i n m a n y studies. N o t taking

t h e m i n t o consideration, especially at school, causes great problems for the individuals

concerned, for example, b o r e d o m due t o lack of stimulation and social isolation f r o m non-gifted

peers. These are exemplified by a n u m b e r of case studies.

Finally, problems i n identifying interindividual talent differences as w e l l as related questions

of equality are discussed. I n his c o m m e n t a r y , Edward Necka supplements the interindividual

a p p r o a c h w i t h a n mfraindividual a p p r o a c h w h i c h is especially i m p o r t a n t f r o m the developmental p o i n t of view. F u r t h e r m o r e , the discussant emphasizes t h e necessity of n o t only taking

quantitative but also qualitative

differences i n t o consideration, p o i n t i n g out as one example

metacognitive factors (see also t h e c o n t r i b u t i o n f r o m C h r i s t o p h Perleth, below). Necka

r e c o m m e n d s using characteristics of t e m p e r a m e n t t o study "preconditions of talent", whereby

a "general energy" - apparently i n the sense of Russian research o n giftedness - is assumed.

I n the c o n t r i b u t i o n w h i c h follows b y Andrzej Sekowski, a review of the s y m p o s i u m "Structures

a n d processes i n intellectual achievements" is presented. T h i s deals n o t only w i t h cognitive skills

but also cognitive styles a n d strategies i n solving complex tasks i n various achievement settings

a n d w i t h various age groups. I n his second contribution, Sekowski reports about his o w n

empirical studies for predicting various achievement contents. A c c o r d i n g t o this, predictors vary

according t o domain-specific achievement criteria, e. g. i n m a t h or humanities. T h e n , studies

14

Introduction

are presented by Katya Stoycheva w h i c h are concerned w i t h the relationship between creativity

and intelligence. Based o n test theoretical data, influences of creative m o t i v a t i o n a n d the need

for achievement o n this relationship are analyzed using correlational methods. T h e results are

presented for discussion.

Finally, C h r i s t o p h Perleth reports about three studies w h i c h investigated central metacognitive

competencies, especially m e t a m e m o r y i n kindergarten a n d grade school children. Whereas the

first t w o studies provide m o r e i n f o r m a t i o n about the early development of metacognitive

competences, the m a i n result of the t h i r d (training) study is probably m o r e interesting f r o m a n

educational a n d nurturing p o i n t of view. Training effects could be s h o w n i n various talent levels

especially for near transfer tasks; the superiority of gifted students first became apparent w i t h

increasing transfer distance. In conclusion, some consequences for the classroom - for b o t h

n o r m a l children and the learning disabled - are discussed.

Individual differences in talent

Hansgeorg

German

Bartenwerfer

Institute

for International

Educational

Research,

Frankfurt/Main,

Germany

Definition

T h e t o p i c of this presentation is "Individual Differences i n Talent". First w e have t o take a l o o k

at t h e concept "talent". W h a t does it m e a n t o say " A is musically talented" o r " B is a talented

speaker", etc.? Such statements m e a n that someone possesses g o o d preconditions for perform i n g w e l l i n t h e corresponding area - e. g. i n music. These prerequisites for h i g h performances

are generally considered t o be connected w i t h one particular p e r s o n . W e w i l l n o t be speaking

about talents i n groups - e. g. for particular races - since the t o p i c here is individual differences

i n talent. W e c a n thus define "talent" i n the following way:

Talent is t h e s u m of all individual conditions w h i c h can enable one t o p e r f o r m outstandingly

i n m e n t a l , artistic or physical areas.

Such individual conditions are, for example: intelligence, creativity, social ability, knowledge,

interests a n d m o t i v a t i o n , perseverance, concentration, stress resistance, vitality, e m o t i o n a l

stability, physical and m e n t a l health, physical stature.

I w a n t t o add a definition f r o m Professor Rainer Ortleb, the present Federal Minister for

Education a n d Science, w h o stresses even m o r e the individuality of talent. Ortleb ( 1 9 9 2 , p . 6),

i n his preface t o K u r t A . Heller's b o o k "Giftedness i n C h i l d h o o d and Adolescence" (Hochbegab u n g i m Kindes- u n d Jugendalter), w r o t e that giftedness is a concept for t h e fact "that there are

individuals w h o are capable of unusual achievements i n intellectual, creative, p s y c h o m o t o r , or

social areas, t h a t others are incapable of, even w i t h better educational opportunities or greater

personal exertions".

T y p e s of talent

T h e n u m b e r of types of talents has probably never been counted: T h u s , one can say, there

are uncounted types of talents. Everything w e do i n life, w i t h i n and outside of our professions,

c a n be carried out i n a m o r e or less talented m a n n e r . I n our society, however, talent i n

professional lifes are h o n o r e d m o r e t h a n , for example, talents i n hobbies. Therefore, w e will

begin w i t h talent i n professions. Individuals w h o achieve outstandingly i n t h e i r field s o o n notice

it i n cash o r other n o n - m o n e t a r y rewards, such as recognition or prestige. A l m o s t everyone is

pleased t o receive prestige or lots of m o n e y , or b o t h .

Each day shows us that there really are different types of talent. T h e successful conductor

certainly needs other talents t h a n a great mathematician. T h e same holds true for a highly

ranked tennis player versus a n entrepreneur w h o makes a large profit b y p r o d u c i n g w o o d e n

matches. Different types of talent are needed, for example, by a famous portrait painter and a

chess c h a m p i o n , the successful politician c o m p a r e d w i t h a novelist.

T h o s e w h o t h i n k about various types of talent should n o t be misled i n t o t h i n k i n g there are

o n l y special types of talent. T h i s k i n d of assumption does n o t do justice t o some types of great

talent. Certainly there are very special talents such as those of excellent mathematicians w h o

are incapable of dealing w i t h other areas of life. B u t there are also talented individuals w h o

Hansgeorg

16

Bartenwerfer

excel i n m a n y areas. Classical examples of this are Leonardo da V i n c i o r Goethe. B u t this is

n o t only true of t h e past; t h e Studienstiftung

des deutschen

Volkes has demonstrated since

the twenties that there are n o t only special talents but also that the s u p p o r t and challenge of

broader talents is essential.

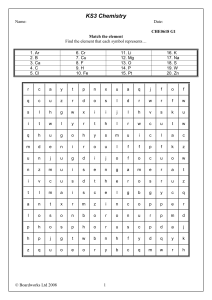

Figure

1:

Different types of giftedness (talent)

Causes of individual talent differences

In order t o understand various types of talent as well as special versus general talents, it is

useful t o view the causes of talents. W e k n o w today that m a n y causes have t o c o m e together

t o really be able t o speak about talents. T h e following figure m a y be useful for understanding

this: T h e most i m p o r t a n t factors are presented broadly w h e r e it is k n o w n that they are

meaningful for t h e development of particularly high achievements.

T h e meaning of various causes of talent

T h e boxes i n the t o p r o w of figure 2 and those o n the left are n o t of equal i m p o r t a n c e . O f

the three t o p boxes, the one o n the left is n o doubt of the greatest i m p o r t a n c e . M u c h of the

g r o u n d w o r k for later development is laid during the first years of life. A review by Christopher

Jencks et α/. ( 1 9 7 2 ) explained u p t o 5 0 % of the variance of educational achievement using

family background.

Individual differences i n talent

17

family

background

genetic

background

health

vitality

interests, motivation

perseverance

concentration

intelligence, creativity

learning speed

knowledge and

"fore-knowledge"

ζ

especially high performance

Figure

2:

Causes of h i g h m e n t a l performances

T h e second most i m p o r t a n t factor, according t o most researchers, is a child's genetic

background. W e do n o t k n o w m u c h yet about h o w genes influence m e n t a l abilities. This

probably takes place m o r e o r less indirectly. A n example: Verbal talent i n adults is often linked

t o the frequency w i t h w h i c h the mothers speak t o t h e young child. If t h e child speaks little for

genetic reasons, i.e. hardly opens its m o u t h , t h e n the mother will tend t o speak less t o the child.

W h e n there is a response, m e a n i n g it is pleasant and interesting t o speak w i t h t h e child, t h e

m o t h e r w i l l speak m o r e frequently w i t h it and thus nurture its later verbal abilities. I n this

example, t h e m o t h e r ' s behavior w i t h the child is partially determined b y t h e child's genes. A

direct genetic effect w o u l d be w h e n the number of nerve cells i n the central nervous system and

their interconnections w e r e genetically determined. T h u s , the genetic background effects a child

b o t h directly a n d indirectly.

Educators m a y find it dissatisfactory that the factor "school" plays less of a role t h a n the factor

family background. This does not m e a n , however, that school is of n o i m p o r t a n c e . T h e

i m p o r t a n c e of t h e school can be very great i n m a n y individual instances. T h e statement that

the genetic equipment has a greater effect o n talent development t h a n t h e school e n v i r o n m e n t

is only a statistical finding. This does n o t tell h o w the development of talent w i l l proceed i n a n

individual child.

I n order t o m a k e it clearer that a great deal of importance is t o be placed o n various causes

of talent development w i t h regard t o cognitive inequality, I quote Christopher Jencks and

colleagues ( 1 9 7 2 , p . 180), w h o i n m y o p i n i o n , carried out t h e largest and most neutral

international study (retranslation f r o m G e r m a n i n t o English):

"(1) If w e could make everybody have the same genes, then t h e inequality of test results w o u l d

probably d r o p by 3 3 t o 5 0 percent.

18

H a n s g e o r g Bartenwerfer

(2) If w e could provide everyone w i t h the same total e n v i r o n m e n t , t h e n t h e inequality of test

results w o u l d probably d r o p 2 5 t o 4 0 percent.

(3) If w e only equalized the e c o n o m i c status of every p e r s o n , t h e inequality of test results w o u l d

only d r o p by 6 percent o r less.

(4) If w e provided everyone w i t h the same a m o u n t of s c h o o l i n g , t h e cognitive inequality i n

adults could be decreased by 5 t o 1 5 % percent w h i c h is, h o w e v e r , a very generous estimate.

(5) If w e could equalize the quality of all grade schools, t h e cognitive inequality w o u l d be

reduced b y 3 percent or less.

(6) If w e could m a k e the quality of h i g h schools equal, t h e n t h e cognitive inequality w o u l d be

reduced by 1 percent or less."

Most of the differences i n the adults' test results are due t o factors w h i c h t h e s c h o o l does n o t

control. This does n o t m e a n that schools could n o t equalize t h e test scores i f t h e y a t t e m p t e d

t o do so. Probably they could. If w e w a n t e d everyone t o read at t h e present n a t i o n a l average,

t h e n w e could provide very gifted children w i t h only o n e o r t w o years of s c h o o l i n g , children

w h o are somewhat above average w i t h six years, those w h o are s o m e w h a t b e l o w average 1 2

years, a n d t h e very slow ones, 1 8 years or m o r e . "We assume t h a t such measures w i l l greatly

reduces the inequality of reading results. W e still do n o t vote for such solutions. 'Equal

o p p o r t u n i t y ' means t o us that every individual has a chance at as m u c h e d u c a t i o n as he/she

wants. (However) such a c o m p r e h e n s i o n of equal o p p o r t u n i t y guarantees unequal results."

(Jencks et al. 1 9 7 2 , p . 161f., retranslation f r o m German).

T h e degree of individual talent differences

Individual talent differences c a n be incredibly large. T h i s is suppressed o r i g n o r e d again a n d

again by teachers. L e t us examine some examples of particularly h i g h degrees of m e n t a l intellectual-cognitive ability. This ignores all cases of special musical o r s p o r t talents. T h e y

generally do n o t cause any difficulties, because particular musical o r s p o r t talents i n o u r society

are generally accepted - i n contrast t o outstanding mental-intellectual-cognitive talents. I n m a n y

places, early musical or sporting talents are scouted for i n order t o n u r t u r e t h e m f r o m a n early

age. I also neglect examples of famous personalities because t h e y are already w e l l k n o w n . I w i l l

only present a few examples of early observable talents t h a t have occurred i n o u r lifetimes a n d

could cross any of our paths.

I will first quote the news agency, Reuter f r o m December 1 9 8 1 , ' T h e best of 5 3 0 candidates

i n the entrance e x a m i n a t i o n for mathematics at t h e University of O x f o r d w a s ten-year-old R u t h

Lawrence. R u t h w i l l be able t o begin studying i n O c t o b e r 1 9 8 3 as a twelve-year-old." T h i s

means that this ten-year-old was better i n these exams t h a n applicants a p p r o x i m a t e l y twice h e r

age, and that i n c o m p e t i t i o n w i t h 5 3 0 of t h e m .

I n August 1 9 8 2 , one could read the following r e p o r t f r o m the Deutsche Presse A g e n t u r (dpa).

" A Soviet 12-year-old was given special permission f r o m h e a l t h authorities t o b e g i n studying

medicine. H e learned his A B C ' s i n a few days a n d c o m p l e t e d his s c h o o l i n g i n half t h e n o r m a l

t i m e - w i t h t o p grades." I n the Soviet U n i o n , one was n o r m a l l y n o t allowed t o study medicine

until at least t h e age of 1 8 . T h e application for special p e r m i s s i o n t o b e g i n earlier and t h e

considerations that had t o be made, brought this i t e m t o t h e a t t e n t i o n of t h e press.

A n o t h e r dpa r e p o r t f r o m September 1 9 8 5 : " A thirteen-year-old b o y f r o m S i m f e r o p o l o n t h e

C r i m e a n sea has begun studying at the Moscow Physical-Technical University. A s t h e East

G e r m a n news service A D N reported o n Monday, t h e b o y learned t o read a n d w r i t e w h i l e still

at kindergarten. H e started school w i t h the t h i r d grade a n d finished 1 1 grades i n six years."

Individual differences i n talent

19

I n A u g u s t 1 9 8 5 , t h e r e w a s a n article by A x e l Hacke i n the Süddeutsche Zeitung. I quote f r o m

this article: " T h e Fu-Fable was n o t appreciated by Peter. This is a little strange because this

b o o k is greatly enjoyed b y H a m b u r g grade schoolers. F u is a friendly yellow being. H e teaches

t h e little ones t o read so t h a t t h e y are soon having n o p r o b l e m w i t h ' F u calls Fara'. Peter,

h o w e v e r , d i d have one p r o b l e m w i t h this, i n that, at the age w h e n all his classmates w e r e fighting

t h e i r w a y t h r o u g h F u sentences, Peter had already read all of Jules V e m e ' s books i n t h e adult

versions. T h i s usually t o o k place i n the following manner: I n the m o r n i n g he picked u p a novel