The

C a 11

to

Discernment

in Troubled Times

New Perspectives on the

Transformative Wisdom

of Ignatius of Loyola

DEAN

BRACKLEY

A Crossroad Book

The Crossroad Publishing Company

New York

23

+ Learning to Love Like God

And the one who was seated on the throne said,

"See, I am making all things new.

(Rev. 21 :5)

11

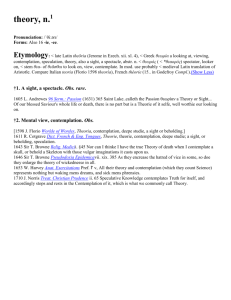

The Contemplation for Attaining (or Arousing) Love of God [230-3 7]

is "the conclusion and apt climax" of the Spiritual Exercises. 1 Like the

Foundation and Two Standards on which it builds, this Contemplation

inculcates a new vision and way of life. Its purpose is to help us sense

God everywhere in all our activities, and to "love and serve in every­

thing" [233] in response; or, according to three well-known lgnatian

catchphrases, to find Cod in all things as contemplatives in action in

close familiarity with Cod.

The Contemplation functions in the Exercises as a kind of Pente­

cost - not a contemplation of the event recounted in the Acts of the

Apostles, but an invitation to experience something like it,2 that is, to

experience God's self-gift (as Holy Spirit) and to see the world with

new eyes. The Contemplation invites us to experience how "God is

love" and labors in the world for abundant life.

THE CONTEMPLATION FOR ATTAINING LOVE

Cod is love.

(1 John 4:8)

Before presenting the Contempla\ion, Ignatius reminds us of two truths

about love. First , "love ought to be expressed in deeds more than in

words" ([230]; see John 14:21; 1 John 3:18). Second, "love consists in

a mutual sharing of goods; that is, the lover gives and shares with the

beloved what he or she has, or out of what he or she has or can do,

and vice versa, so that if one has knowledge one gives to the other

who does not have it. The same with honors and with riches, and the

other reciprocates in the same way" [231 ].

212

,,

213

Learning to Love Like Cod

Commentary. If love is shown in deeds, then contemplating God's

love means contemplating God's deeds, especially how God bestows

gifts on us. God's love should stir up active love in us.

Love consists of mutual sharing. God shares "knowledge" of real­

ity in this Contemplation. It is surprising to read that lovers share

"riches" and "honors" - the two key temptations in the Two Standards

[142]! The emphasis is obviously on sharing. We can understand shar­

ing riches - but what about ·honors? Love "honors" others; it accords

them respect, perhaps our deepest human need. A friend once recom­

mended imagining all people wearing signs around their necks reading

"Take me seriously!" Love recognizes, above all, the dignity of those

the world despises. Love listens to their stories - which is often all

they have.

The main body of the Contemplation is preceded by two brief

introductory steps, the composition and the grace sought.

The "composition." After first asking God to direct everything to the

ultimate goal of life, we next imagine a scene to keep our attention

focused [232]. Ignatius suggests imagining ourselves before God and

the saints in glory.

The grace sought. Next (as in every exercise), we ask for what we

want. Ignatius suggests that we request "interior knowledge of so much

good received, in order that, entirely conscious of that, I may love and

serve God in everything" [233].

Commentary on the "grace" requested. The purpose of the Contem­

plation is to arouse love in us; to become so aware of God's love that

we are moved to respond by loving in the same way. 3 We ask to love

and serve "in everything" (en todo)- that is, not just in response to

forgiveness (the First Week) or to love Christ in order to follow him

more closely "(Second, Third, and Fourth Weeks), but to love and serve

God in everything, in everyone, and in every aspect of daily life.

The body of the Contemplation consists of four points, which are

four perspectives fro_m which to consider God's love.

•

The first point is to recall the blessings we have received in our

life.time, the blessings "of creation, redemption, and personal gifts,"

reflecting that all this comes from God's hand and demonstrates how

much more "the Lord desires to give himself" to us. We then reflect on

!

!

I

214

Resurrection

how it is only reasonabl� to offer God in return everything we have,

and ourselves with it, just as God has done. With as much feeling as

possible, we then make the following offering:

Take, Lord, and receive all my liberty,

my memory, my understanding, and my whole will,

all that I have and possess.

You gave it to me;

to you, Lord, I return it.

It is all yours; use it as you please.

Give me your love and your grace;

this is enough for me. [231]

Commentary on the first point. In twelve-step programs like Alco­

holics Anonymous, participants take inventory of their past. They try to

come to terms with both the damage they have done and their happy

debt of gratitude to those who stood by them despite everything (com­

pare [60] in the Exercises). The first point of the Contemplation is an

exercise in reappropriating the past. Our new situation helps us see

God's hand where we never did before. God has always been there,

guiding and helping us, when we were largely uhaware of it.

Few things humanize like gratitude, which is rarely inappropriate and

difficult to overdo. Growing up in an affluent society, we frequently

take for granted what most people through history could not and can­

not: good nutrition, decent health, a measure of economic security,

and life itself. From taking these things for granted it is a short step to

supposing life owes us that and more. Then, instead of giving thanks

for the most basic things, we let any snafu ruin our day. We have re- __

ceived everything as a gift. Poor people - grateful to be alive, to eat, /

to enjoy family and the beauty of nature - are our professors in the _J

school of gratitude.

In the first point, we recall the blessings of "creation, redemption,

and personal gifts" (which may refer to gifts from Father-Creator, Son,

and Spirit, respectively). The principal gift is God's Self. God's self­

communication is the ultimate meaning of God's dealings with the

universe. Each in a different way, the three Persons of the Trinity invade

history and our personal lives, dwelling in us and making us dwell in

Learning to Love Like Cod

215

God - as the Eucharist and Pentecost illustrate. The remaining three

points of the Contemplation develop this idea of God's self-gift.

Whereas the "indifference" of the Foundation [23] is a freedom

from, the prayer "Take and receive" specifies that this freedom is for

giving ourselves and our lives to God. This is not about renouncing

memory, intellect , will, and freedom, however, but enlisting these, with

all our creativity, in service. "Give me your love and your grace" seems

to mean: "Give me love for you and grace to love you."4

• The second point (which might constitute the subject of a

different exercise altogether) is:

to observe how God dwells in creatures: in the elements giving

being, in the plants vegetating, in the animals feeling, in humans

giving understanding; and so in me giving me being, life, and

feeling and making me to understand; and similarly making me a

temple, having created me in the divine image and likeness. [235]

We reflect on these matters, seeking what we want, and closing (as

we are able) with the prayer "Take and Receive."

Commentary on the second point. Here, too, the idea is to sense

how God is present in everything and everyone, making each be what

it is. God gives everything its being out of love, moment by moment

(J. Tetlow), and dwells in each gift. God blows in the breeze and flows

in the streams; God leaps in the frogs and flies in the birds; God thinks,

loves, and communicates in human beings. As the Mayan Indians say,

God is Corazon de la montafia, Corazon def cielo - "Heart of the

Mountain" and "Heart of the Sky."

• The third point is to "consider how God works and labors for

me in all created things on the face of the earth." Ignatius says God

"behaves as a laborer does," working in minerals, plants, animals, ac­

cording to the nature of each [236]. We then reflect and close with

the usual prayer.

Commentary on the third point. God labors in everything to bring

all creation to fruition. Jesus perceived his Father working to give life

(John 5:17), making the sun shine and sending the rain to fall on good

and bad alike (Matt. 5:45). This suggests God's solidarity with workers

l

!

!

216

Resurrection

who continue the divine work of creation. It also invites us to reflect on

our proper place and role in the world in relation to other creatures.

• The fourth point is "to observe how all good things and gifts de­

scend from above, for example my limited powers from the divine and

infinite power on high, and likewise justice, goodness, mercy, compas­

sion, etc., just as rays descend from the sun and waters from the spring,

and so on" [237]. Once again, we reflect and converse with God as

seems fitting.

Commentary on the fourth point. All goodness participates in God's

goodness and reveals God as its source, especially moral good­

ness: "justice, goodness, compassion, mercy" [237]. According to the

apostle James, "Every generous act of giving, with every perfect gift,

is from above, coming down from the Father of lights" (James 1 :17).

In this point, the motive for loving God is not the gifts or what God

does, but who God is.

+++

These four points, which are really four exercises, aim to foster a deep

appreciation of God's gifts and of God as the principal gift in all gifts.

According to the Foundation [23 ], creatures can divert us from our final

goal; according to the Contemplation, all creatures are sacraments by

which God tomes to us. The Foundation bids us use all creatures to

serve God; the Contemplation presents God laboring in all creatures--to serve us.5 Created reality- things, people, events- is not a screen ..

that God hides behind to then peek out at us. God is present in all

creatures and events and comes to us in and through them. "The world

is charged with the grandeur of God," wrote the poet Gerard Manley

Hopkins. The Contemplation invites us "to seek God our Lord in alll 1

things, ... loving him in all creatures and all creatures in him." 6 Created

reality has in itself an inexhaustible depth and richness at the hearf.J

of which we find Cod. The Contemplation fosters seeing (and feeling

and hearing, etc.) this richness and growing more aware of God loving

us in and through everything that exists and everything that happens

(sometimes despite things that happen). This awareness awakens the

response of grateful love and service to the world.

Learning to Love Like God

217

More specifically: in all things and daily events, God offers us the

Kingdom, a new creation. Present and laboring in all things and events,

God makes forgiveness,

love, community, justice, and peace possible.

When we accept the offer, by loving and serving in response [233],

the Reign of God happens here and now. In this way God makes all

things new (cf. Rev.

21 :5).

THE CONTEMPLATION AND

THE PASCHAL MYSTERY

God has made known to us the mystery of his will, ...

to gather up all things in Christ.

(Eph. 1:9-10)

The place of Christ in the Contemplation has been the subject of de­

bate since soon after Ignatius's death. At first glance, there appears

to be no mention of Christ. 7 Is he absent from the Contemplation?

No. In fact , the cryptic references to Christ provide us with clues to

developing the Contemplation's social implications. What are these

references?

The first point includes the "blessings of redemption," which are

summed up in Christ himself.8 He is also the most complete example

of Goo's presence in the world, which is the subject of the second

point. According to the traditional (scholastic) schema implicit in point

two, Christ is the key to understanding how God dwells in all creatures.

However, biblical thinking and good Christian theology seek God's

presence not simply in persons and things but also in historical events

and processes. God acts and saves in history. Therefore, the third point

of the Contemplation speaks of "how. God works and labors for me,"

how God "behaves as a laborer" [236]. This recalls the Third Week,

when the retreatant "frequently call[s] to mind the labors, the fatigue,

and suffering which Christ endured" [206]. 9 According to John's Gos­

pel, Jesus and his Father labor to bring life to the world: "My Father

is still working, and I also am working" (John 5:1 7), and God's saving

presence is most clearly revealed in the labor of Jesus' passion and

death and in his resurrection

-I

l

(cf. John 17:1 ).

I

.!

t

220

Resurrection

The third point therefore gives the distinctly Christian clue to finding

God "in all things." (The other three points, though also Christian, are

compatible with non-Christian cosmologies. 11) God's saving presence

in history is disclosed above all in Jesus' cross and resurrection and

in the crosses and resurrections - the ongoing paschal . mystery - of

suffering and struggling humanity. God's glory shines forth from the

worn faces of those who labor, like God, to bring creation to fruition,

often under unjust conditions. Divine glory shines in the victims of his­

tory, the poor and meek ('anawim) who refuse to adopt the methods

of their assailants. And it shines, above all, in those who suffer and

even die for what is right. In these ambassadors (Matt. 25) who com­

plete what is lacking in Christ's sufferings (Col. 1 :24) God draws near

in mercy.

We cover retreat house walls with landscapes, tropical flowers, and

koala bears, whose beauty surely points to their Creator. What about

giving equal space to crucified-and-rising people and images like Fritz

Eichenberg's print "The Christ of the Breadline," which portrays Christ's

presence among our urban outcasts?

Every butterfly and blade of grass reveals the God of Jesus, but onl;\

if we can recognize God in broken human beings as well. We can avoid

the God of Jesus in sunsets and flowers, if we try, but not in the poor

who place us unavoidably before that God. If we cannot recognize

God's face there, it is doubtful that any butterfly on earth will reveal

the God of Jesus to us. When we can find God in our jails and AIDS

hospices, we can find God coming to meet us everywhere else.

We all suspect that the world is a crueler place than we dare to

admit. Since the poor confront us with this evil, it is tempting to avoid

th.em. But if we let their stories break our hearts, they can open our

eyes to marvels we scarcely dared imagine. They reveal the revolution

of love that God is bringing about in the world.

There is a lot of dying going on, but a lot of rising as well. That is the

deepest meaning of history and of our lives. But we perceive the daily

resurrections only if we open our eyes to the crucifixions. To share the

hope of the poor, we must let their suffering move us. and place us

before the Holy Mystery laboring among us.

J

..

221

Learning to Love Like Cod

CONCLUSION:

A WORLD CHARGED WITH GOD

As we have seen, Ignatius calls the Spirit by other names, especially

in early and published writings. Some detect veiled references in this

Contemplation. Its title, the first preliminary note [230], and the first

point (including the prayer "Take and Receive") speak of love, gifts (in­

cluding self-gift), and sharing (communio), applying these expressions

to God. These same words - Love, Gift 1 Communio - have been used

to identify the Holy Spirit since the time of Augustine. 12 The second

point of the Contemplation recalls that God makes of us a temple, a

clear reference to the Holy Spirit.

Once we recognize the Contemplation for Attaining Love as a Pen­

tecost exercise, the overarching trinitarian structure of the lgnatian

Exercises becomes clear, as Jose Marfa Lera says: "The Father, in the

loving divine design, traces the plan of creation (Principle and Foun­

dation [23]). The Son realizes that plan and invites human beings to

follow him (the central and most important section of the Exercises)."

Finally, the Spirit realizes God's plan in and through us, making us

"daughters and sons in the Son, ... 'loving [God] in all things and all

things in [God] ... '" (Contemplation for Attaining Love). 13 The Foun­

dation reveals the Creator's plan; the subsequent Weeks reveal Christ;

the Contemplation reveals the Spirit.

The Contemplation rounds out the Foundation. Whereas the latter

states that we are created "to praise, reverence, and serve God" [23],

the former specifies that this means to "to love and serve in every­

thing" [233]. Whereas, according to the Foundation, we should use

creatures only to the extent that they aid our salvation, the vision of

the Contemplation is richer: We are to "love and serve in everything"

out of gratitude, that is, love all creatures in God and love God who is

working in all of them (cf. Const 288).

However, if the Contemplation is primarily about the Spirit, it is

also eminently trinitarian. It invites us to perceive reality with new

eyes, which is the work of the Spirit who guides into all truth (cf. John

16: 13). What our new eyes see, however, is the Creator giving _us all

good things through the Son. Above all, it is through the Son that the

!

!

!

!

222

Resurrection

Father communicates the Spirit (God's self-gift) to us. We respond to

God's gift by "loving and serving in everything" [2331' filled with the

Spirit who remakes us in the image of Christ. Like the Contemplation,

these trinitarian formulae express the way a self-giving God invades

realit y- especially ourselves - and labors to transform it.

God presses upon us, permanently, inviting us to respond by

habitually seeking out and acting on God's purpose. Prayer and con­

templation are obviously integral to this vision of life, and doing

without them would be an evasion of realit y. On the other hand, we

do not withdraw from the world of action in order to pray, since it is

precisely in the world that God is to be found.

We now turn to the subject of prayer itself.