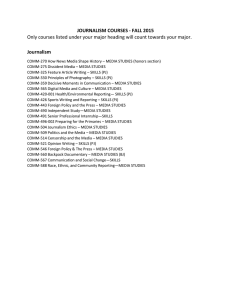

807353 research-article2018 JOU0010.1177/1464884918807353JournalismHanitzsch Representativeness Journalism studies still needs to fix Western bias Journalism 2019, Vol. 20(1) 214­–217 © The Author(s) 2018 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918807353 DOI: 10.1177/1464884918807353 journals.sagepub.com/home/jou Thomas Hanitzsch LMU Munich, Germany Granted, studying journalism without any sort of ethnocentric bias is an epistemological impossibility. Just like all human beings, researchers bring their own selves to bear on the object of study. As scholars, we tend to calibrate our understanding of journalism to a convenient set of familiar concepts and cultural experience. This does not necessarily need to be a problem. In an ideal scholarly world, all voices compete in academic discourse regardless of geographic and linguistic origin, ultimately leading to a truly cosmopolitan vision of journalism and news production. Unfortunately, this is not the world we live in. In this short essay, I argue that, despite successful efforts to internationalize the field in terms of quantity, journalism studies is still struggling with the consequences of a continued Western hegemony in the way we approach and understand journalism on a global scale. This hegemony, understandable its reasons are, is doing the field a disservice. Most of what we know and take for granted in the Western world, but also elsewhere, about ‘journalism’ rests on concepts and evidence generated from within Western concepts and experience. Despite globalization, Western countries are still the dominant sites of both the production and subject of research in the field. In part, this Western dominance has resulted from, and is reinforcing, a concentration of academic and textbook publishers in the Anglo-Saxon world using English as the default language. Furthermore, the culturally asymmetric recognition of academic research and intellectual authority in global knowledge production give scholars from the Global North a considerable advantage. Western researchers often take it for granted that their work is relevant to readers around the world, while researchers from non-Western contexts often have to defend their choice of countries and country-specific literatures. Western publications, particularly journal articles, have a structure, format, and academic writing style as well as a quantitative methods bias that non-Western researchers may not always be trained in or be acquainted with, making it difficult for them to publish in journals that offer their work greater visibility. Corresponding author: Thomas Hanitzsch, LMU Munich, 80539 Munchen, Germany. Email: thomas.hanitzsch@ifkw.lmu.de Hanitzsch 215 Browsing through the field’s major publication outlets yields impressive evidence of the field having become much more international than, say, 25 years ago. Part of this move toward globalization is a growing number of publications coming out of the nonWestern world. However, despite an increasing quantity of publication output from the Global South, its qualitative impact on the field is still relatively minor. By far, most of the studies we typically consider groundbreaking or field-defining were authored by scholars from the West. Internationalization in journalism studies has largely taken place within the confines of the Western world, with European scholars gradually gaining weight in international associations and academic journals. Even so, US scholarship still reigns supreme when it comes to defining key areas of inquiry (such as ‘fake news’ and verification, most recently) and to directing the field in theoretical, epistemological, and methodological terms. The paucity of recognition of non-Western scholarship is also reflected in the way journalism scholars recognize and distribute scholarly prestige. The dominance of US scholarship is particularly noteworthy. While currently more than 52 percent of the members of the International Communication Association’s (ICA) Journalism Studies Division are working in institutions outside the United States,1 the field’s symbolic capital, indexed through major awards honoring scholarly achievement, tends to be allocated to researchers based or trained in the United States. Between 2011 and 2018, ICA’s Journalism Studies Division has given all of its book, dissertation, and outstanding article awards to scholars from universities located in the West. Of the 20 major awards, 13 went to US researchers.2 Arguably, this Western dominance, and the uneven coverage of world regions by researchers, has consequences for our understanding of journalism. ‘International’ journalism research, still too often, problematizes journalism from within the Western experience and a Western analytical framework. Western cultures of journalism, and particularly the news media in the United States, have become the prism through which we have constructed normality with respect to how we understand journalism globally. This framework builds on the idea of the separation of powers, accomplished through a system of checks and balances. Grounded in a liberal pluralist view, journalism is seen as essential to the creation and maintenance of participatory democracy. Acting as Fourth Estate alongside the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of power, this understanding assumes that the news media are independent of the state and that journalists are autonomous agents who represent the people. This approach privileges liberal democracy and individuality, which may be different from norms that exist elsewhere as exemplified by the debate over the value of development journalism. For many countries newly emergent from colonialism, development journalism, based on a collectivistic precept, was one way to overcome the destitution left behind by colonialists, but for many in the West it represented a stifling of the press by government. One will, therefore, have to understand that the genesis of theory, research, and practice in the field of communication, and thus also of journalism, lies in Western tenets. The Western experience has even become a standard against which we tend to gauge journalism and the news in other regions of the world. As a result, journalistic cultures in some, mostly developing and transitional societies are sometimes portrayed as needing to ‘catch up’ with the norms and practices celebrated by the West. 216 Journalism 20(1) Nowhere is the problem of generalizing and exporting the Western view to other parts of the world more obvious than in academic and professional discourses lamenting a crisis of journalism. Responding to unsettling developments in selected Western countries, scholars have issued calls for ‘rebuilding’, ‘reconsidering’, ‘remaking’, ‘reconstructing’, ‘rethinking’ and ‘reinventing’ journalism (Alexander et al., 2016; Anderson, 2013; Boczkowski and Anderson, 2017; Downie and Schudson, 2009; Peters and Broersma, 2013; Waisbord, 2013), and even for ‘rethinking again’ (Peters and Broersma, 2017). The alarmist tone of this debate may well be appropriate in parts of the Western world, notably the United States, but the situation in many other countries may not necessarily call for such a response. The political and economic conditions of journalism in the United States, as well its historical tradition and cultural mythology, render the US media system substantively distinct, if not exceptional, when put in comparison with other nations, including those in the West (Curran, 2011). While traditional journalism may be contracting in large parts of the Global North, the industry is still expanding in many developing nations, such as China and India. Through journalism studies’ obsession with problems experienced in the West (such as shrinking revenue, a loss of media trust and journalistic authority, competition from social and ‘alternative’ media, and a growth of precarious labor), the field is ignoring some of the really burning issues faced by journalists and news organizations in other parts of the world. Among these problems are issues of journalists’ safety and impunity, declining press freedom and the return of censorship, as well as clientelism and instrumental use of the media by politicians. Other issues are more broadly related to the social conditions of journalism, such as authoritarian resilience, pervasive corruption, low human development, and strong socio-economic inequalities. Hence, the proclaimed crisis of journalism may actually be, at least in part, a crisis of the professional paradigm celebrated by journalists in the West, and – by extension – the expression of an intellectual blind spot in journalism scholarship. Shrinking public confidence in the news and the erosion of journalism’s epistemic authority to speak truth, for instance, may less be a universal phenomenon but one specifically related to a general crisis of democratic institutions in parts of the Western world. Journalism studies as a field can, and must, do better to become truly international, not just in quantitative terms (conference attendance and publication output), but also by recognizing a global diversity of journalistic cultures and intellectual thought lines that look beyond North America and Western Europe. Studying journalism from a non-Western perspective should be more than just a sideline of journalism research; it has the potential to call into question key assumptions about journalism that we have long taken for granted. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Notes 1. 2. E-mail exchange with ICA Member Services, from 18 December 2017. https://www.icahdq.org/members/group_content_view.asp?group=186103&id=631059. Hanitzsch 217 References Alexander JC, Breese EB and Luengo M (eds) (2016) The Crisis of Journalism Reconsidered: Democratic Culture, Professional Codes, Digital Future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Anderson CW (2013) Rebuilding the News: Metropolitan Journalism in the Digital Age. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. Boczkowski PJ and Anderson CW (eds) (2017) Remaking the News: Essays on the Future of Journalism Scholarship in the Digital Age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Curran J (2011) Questioning a new orthodoxy. In: Curran J (ed.) Media and Democracy (Communication and Society). London: Routledge, pp. 28–46. Downie L and Schudson M (2009) The reconstruction of American Journalism. Columbia Journalism Review 48(4): 28–51. Peters C and Broersma MJ (eds) (2013) Rethinking Journalism: Trust and Participation in a Transformed News Landscape. Abingdon: Routledge. Peters C and Broersma MJ (eds) (2017) Rethinking Journalism Again: Societal Role and Public Relevance in a Digital Age. Abingdon: Routledge. Waisbord S (2013) Reinventing Professionalism: Journalism and News in Global Perspective. Cambridge: Polity Press.