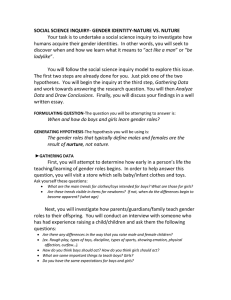

The Psychology of Gender Textbook

advertisement