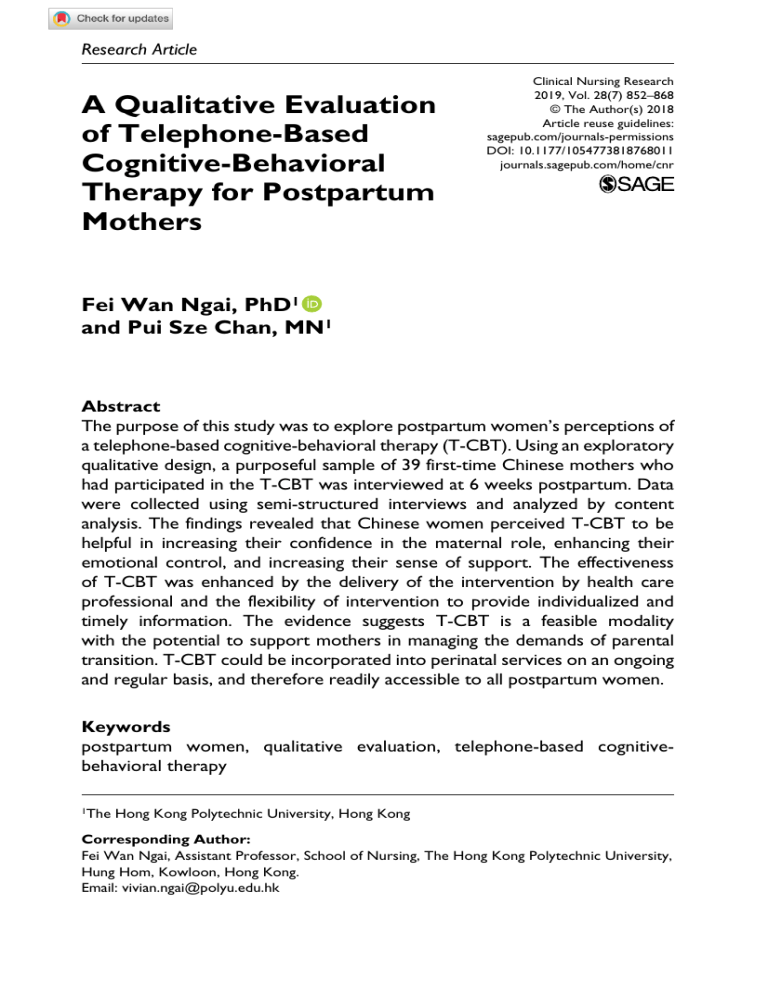

768011 research-article2018 CNRXXX10.1177/1054773818768011Clinical Nursing ResearchNgai and Chan Research Article A Qualitative Evaluation of Telephone-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Postpartum Mothers Clinical Nursing Research 2019, Vol. 28(7) 852­–868 © The Author(s) 2018 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773818768011 DOI: 10.1177/1054773818768011 journals.sagepub.com/home/cnr Fei Wan Ngai, PhD1 and Pui Sze Chan, MN1 Abstract The purpose of this study was to explore postpartum women’s perceptions of a telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (T-CBT). Using an exploratory qualitative design, a purposeful sample of 39 first-time Chinese mothers who had participated in the T-CBT was interviewed at 6 weeks postpartum. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews and analyzed by content analysis. The findings revealed that Chinese women perceived T-CBT to be helpful in increasing their confidence in the maternal role, enhancing their emotional control, and increasing their sense of support. The effectiveness of T-CBT was enhanced by the delivery of the intervention by health care professional and the flexibility of intervention to provide individualized and timely information. The evidence suggests T-CBT is a feasible modality with the potential to support mothers in managing the demands of parental transition. T-CBT could be incorporated into perinatal services on an ongoing and regular basis, and therefore readily accessible to all postpartum women. Keywords postpartum women, qualitative evaluation, telephone-based cognitivebehavioral therapy 1The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong Corresponding Author: Fei Wan Ngai, Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong. Email: vivian.ngai@polyu.edu.hk Ngai and Chan 853 Introduction Transition to motherhood is a time of intense physical and emotional demands that pose critical adaptation challenges for new mothers (Ngai & Ngu, 2013). Some women manage to integrate the developmental tasks of a mother and are satisfied with their maternal roles. However, there are others whose abilities to cope are undermined by stressful demands of motherhood and become depressed in the first month following childbirth (Ngai & Ngu, 2015). Postnatal depression was found to be a worldwide health problem affecting 13% of women (Underwood, Waldie, D’Souza, Peterson, & Morton, 2016). In a longitudinal study of 200 Hong Kong Chinese childbearing couples, 11.5% of women have been reported to suffer from depressive symptoms at 6 months after delivery (Ngai & Ngu, 2015). The impact of postnatal depression on the women can be long lasting and have serious consequences on the psychosocial development of the child (Raposa, Hammen, Brennan, & Najman, 2014). Thus, health promotion activities preparing women for the stress of motherhood and empowering women with coping skills to manage the complexity of maternal role are an urgent priority. Telephone-based intervention has shown itself to be an effective treatment modality for postnatal depression, which offers flexible and accessible individualized care for women in the immediate postpartum period (Logsdon, Foltz, Stein, Usui, & Josephson, 2010; Ugarriza & Schmidt, 2006). In a randomized controlled trial of 325 primary care patients with major depressive disorder in the United States, Mohr et al. (2012) found that telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (T-CBT) was as effective as traditional face-toface cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing depressive symptoms at posttreatment. CBT focuses on changing dysfunctional cognitions and maladaptive behavior, as well as developing problem-solving and coping skills that are believed to play a role in the prevention of postnatal depression (Sockol, 2015). In a systematic review of 48 studies involving 4,937 mothers and fathers, the results showed that parenting programs underpinned by cognitive, behavioral, or CBT produced statistically significant short-term improvement in parental self-efficacy 4 weeks after the birth (Barlow, Smailagic, Huband, Roloff, & Bennett, 2014). A recent systematic review of 36 trials of psychosocial intervention for perinatal depression also revealed promising findings for CBT on parenting and child development (Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic, & Linder, 2017). In a systematic review of 40 qualitative studies on women’s experience of postnatal depression, Dennis and Chung-Lee (2006) found that women did not proactively seek help and they prefer to talk with someone who was nonjudgmental rather than receive pharmacological interventions. The delivery of CBT via telephone has the potential to support mothers by providing 854 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) proactive, flexible, and accessible individualized care. Such support is vital during the early postpartum when vulnerable women may become stressed by child care demands and develop depressive symptoms (Wisner et al., 2013). A randomized controlled trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a T-CBT for first-time mothers who were at risk of postnatal depression (Ngai, Wong, Leung, Chau, & Chung, 2015). The primary outcome was postnatal depression and the secondary outcomes were parental competence, parenting stress, quality of life, and social support. A 5-week telephoneadministered manual-based CBT of 30 min each time was delivered weekly from 1-week to 5-week postpartum by a trained midwife. The T-CBT was associated with significant improvements in postnatal depression, parental competence, parenting stress, and quality of life compared with standard care at 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum (Ngai et al., 2015). Although the results from the quantitative evaluation of the T-CBT intervention are encouraging, it has been recommended that complex interventions should be evaluated with both quantitative and qualitative methods to understand the context in which the individual and multiple components of a complex intervention affect the outcome (Campbell et al., 2007). A qualitative evaluation was conducted to offer additional insight into the success and benefits of T-CBT for first-time mothers. Purpose of Study The aim of this study was to have an in-depth understanding on specific components of the T-CBT intervention that women considered helpful in their preparation for early motherhood. Method Design and Participants Participants of the randomized controlled trial were recruited from the postnatal units of three regional hospitals in Hong Kong between 2012 and 2014, which included primipara with singleton full-term healthy baby (gestation: 37-41 weeks; body weight > 2.5 kg, 5-min Apgar score > 7), aged 18 years or above, married, Hong Kong Chinese residents, able to speak and read Chinese language, and scored ≥10 on Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Women were excluded if they had complications after delivery, had regular psychiatric follow-up, or were currently taking antidepressant or antipsychotic drugs. Participants were randomly assigned to the T-CBT or the control group. The intervention group received usual care and T-CBT, whereas the control group only received usual postnatal care (Ngai et al., 2015). Ngai and Chan 855 Among the 197 women who had completed all five sessions of T-CBT, a purposeful sample of 39 women was invited for an in-depth, semi-structured, telephone interview at 6 weeks postpartum. Purposeful sampling involves interviewing people who have had experience with or are part of the phenomenon of interest, to develop a rich description of the phenomenon (Speziale & Carpenter, 2011). Participants were recruited until data saturation was achieved when additional participants did not uncover new ideas. Main elements of T-CBT included exploring stress and emotional changes during the postpartum period, discussing signs and symptoms of postnatal depression, identifying negative thoughts and techniques for modifying those thoughts, facilitating effective problem solving and decision making to cope with common neonatal problems, and improving communication skills to resolve interpersonal conflict. Data Collection A semi-structured interview guide was developed to facilitate the interview. Examples of questions were “What’s your experience of early motherhood?” “How did T-CBT help you cope with the experience of new motherhood?” “What did you like or dislike most about T-CBT?” “Did you have any suggestions for improvements of T-CBT?” “Would you recommend T-CBT to a friend?” The semi-structured interview guide was reviewed by a panel of experts including two academics in midwifery and mental health nursing, two experienced midwives, and two mothers. The interviews were conducted by a trained independent research assistant. At 6 weeks postpartum, the research assistant telephoned the participants who had completed T-CBT and invited them to participate in a semi-structured interview. The nature and purpose of the study were explained. Once consent was obtained, the interview was conducted via telephone. The participants were encouraged to express their perceived impact of T-CBT in Cantonese. Each interview lasted for about 30 min and all the interviews were audio-recorded. Ethical Consideration Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University and the participating hospital. The nature and purpose of the study were explained. Participants were assured of confidentiality and their right to withdraw from the study at any time with no adverse consequences to their treatment and care. Informed consent was obtained from those who agreed to voluntarily participate in the study. 856 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) Data Analysis and Trustworthiness Data were analyzed using content analysis which was conducted simultaneously with data collection (Speziale & Carpenter, 2011). Interview data were transcribed and analyzed in its original language. This was done to maintain the subtlety and meaning of the women’s voices as accurately as possible. Data were reviewed and coded independently by the researchers. The initial coding was done by noting key meaning of the data in the margin of the transcribed text. Each term, sentence, and phrase representing an idea was identified and grouped into a category for analysis of emerging themes. The two researchers then compared the emerging themes for commonalities and variations, and identified the overall themes that best described the participants’ perceptions of T-CBT. Quotations that are presented in this article were translated into English. The translations retained what the women said with some syntactical corrections. The first author translated the quotations, which were then cross checked by the second author. Trustworthiness is often a concern in qualitative content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). The data in the current study were reviewed and coded independently by two researchers. Themes were identified and compared with ongoing and regular communication to ensure consensus and accurate interpretation of the data, thus, enhancing both the credibility and dependability of the findings. All interviews were conducted by the same research assistant using the semi-structure interview guide to ensure consistency in the process of data collection. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed by the same research assistant to ensure dependability of the findings. Field notes were taken to document observations and describe the interviewer’s personal experience with a particular encounter, which may facilitate data analysis and interpretation. Results Thirty-nine women were interviewed. The mean age of the participants was 32 years (SD = 3.3). All participants had a secondary school education and were employed, which is representative of the general population of postpartum women in Hong Kong (Ngai et al., 2015). The median monthly household income was HK$33,203 (US$4,257). The majority of participants had vaginal birth (76.9%). The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Four main themes emerged from the women’s perception of the T-CBT: (a) benefits of T-CBT, (b) facilitators to T-CBT, (c) barriers to the effectiveness of T-CBT, and (d) suggestions for improving T-CBT. All themes and subthemes are summarized in Table 2. 857 Ngai and Chan Table 1. Characteristics of Participants (n = 39). Characteristics Age, M (SD) Education Secondary Tertiary or university Employment status Unemployed Employed Monthly household income <HK$20,000 HK$20,000-HK$30,000 HK$30,001-HK$40,000 >HK$40,000 Mode of delivery Vaginal delivery Cesarean section % n 32.0 (3.3) 15 24 38.5 61.5 0 39 0 100 7 8 14 10 17.9 20.5 35.9 25.7 30 9 76.9 23.1 Table 2. Themes and Subthemes of the Findings. Themes Benefits of T-CBT Facilitators to T-CBT Barriers to the effectiveness of T-CBT Suggestions for improving T-CBT Subthemes Increased confidence in the maternal role Enhanced emotional control Increased sense of support Delivery of T-CBT by a health care professional Accessibility and flexibility of T-CBT Difficult to meet individual learning needs Busy schedule of mothers Extending T-CBT over a longer postnatal period Note. T-CBT = telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy. Theme 1: Benefits of T-CBT Within the theme of benefits of T-CBT, three subthemes were identified, including increased confidence in maternal role, enhanced emotional control, and increased sense of support. Increased confidence in maternal role. Acquisition of knowledge and parenting skills appeared to be the most important aspect of T-CBT, because it elicited 858 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) the greatest number of responses from the participants. Most mothers (89.7%, n = 35) found the T-CBT helpful because of the advice and guidance provided by the nurse on the practical care of their child, such as feeding, bathing, nappy changing, and the ways of dealing with common neonatal problems. One mother said, I encountered difficulties in breastfeeding . . . my child seemed to have nasal congestion and breathing difficulties . . . the nurse [who delivered T-CBT] taught me how to position my child . . . the correct technique of breastfeeding . . . which was really helpful. (Informant 11) Another mother said, As a first-time mother, T-CBT was really helpful . . . I learnt how to feed my child, burping, how to take good care of my child, how to make him feel more comfortable . . . When my child had hiccups, the nurse taught me different methods to stop the hiccups . . . I tried them and they worked, my child stopped the hiccups. (Informant 22) Knowledge about infant care also enhanced a new mother’s confidence in taking up the maternal role. Some women (46.2%, n = 18) stated that T-CBT provided them with different strategies for handling problems associated with infant care, and this increased their confidence in dealing with difficult situations. A mother said, I felt painful [on my nipple] because of my child’s sucking . . . so I had to supplement with bottle feeding . . . I tried to use the breast pump, but I was not sure whether I was doing it right. The nurse [who delivered T-CBT] reassured me that it was just normal and it would be all right . . . which increased my confidence. (Informant 3) Another mother said, Everything about newborn care was new to me. When I encountered things I could not manage, they were all seemed to be problems to me. When I had gained more experiences or after the guidance and advice from the nurse [who delivered T-CBT], I could handle the problem, and I started to feel less stressed and more confident. (Informant 34) Enhanced emotional control. Participants in this study commented that the skills they learnt in T-CBT, such as positive thinking and problem-solving help them control their emotions when faced with the stress of motherhood. For example, one mother said, Ngai and Chan 859 I tried to make myself happy by stopping negative thoughts . . . actually every problem could be solved . . . I was happy just looking at my baby. (Informant 5) Another woman said, When I was upset by my child’s crying, I reminded myself to think more positively that every child cries . . . (Informant 16) Others also shared their experiences in using problem-solving skills to help them cope with the negative emotion. One said, I tried different strategies and tips provided by the nurse [who delivered T-CBT], such as how to breastfeed my child and whether my child had enough milk or not, which helped me solve the problem and improve my emotion. (Informant 28) Another woman said, During the time when I was “doing-the-month,” I was frustrated every time my child cried, not hating my child, but frustrated . . . then I learnt to control myself, when I started to have the feeling of frustration, I would take a break and ask the domestic maid to help take care of my child. (Informant 7) Increased sense of support. Emotional support was identified for the majority of mothers as an important aspect of the T-CBT. Most mothers (87.1%, n = 34) were very grateful for the support they received from the nurse who delivered T-CBT, as one remembered, I was very worried at the beginning . . . the nurse [who delivered T-CBT] taught me the correct skills in breastfeeding . . . I felt being supported . . . emotional support . . . I felt much better after talking to her. (Informant 9) Talking about feelings and being listened to were appreciated by the mothers, in particular during the first month after delivery. A woman said, T-CBT was very helpful . . . because there was no one that I could really talk to . . . I did not know where to seek help . . . I could not go out because I was “doing-the-month.” (Informant 10) Another woman echoed, T-CBT was very helpful . . . in particular during the first month when I could not go out [because of “doing-the-month”]. When I received the phone call from the nurse [who delivered T-CBT], it was just nice to have someone you could talk to . . . I felt good . . . being supported. (Informant 3) 860 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) Theme 2: Facilitators to T-CBT Facilitators to the T-CBT were identified by the participants. These included the delivery of the T-CBT by a health care professional and the accessibility and flexibility of the T-CBT. Delivery of T-CBT by health care professional. The majority of mothers (64.1%, n = 25) appreciated the delivery of T-CBT by an experienced nurse who could provide professional knowledge, which gave them a feeling of security. A mother said, Ms. Ho [who delivered T-CBT] is a nurse. I had trust in what she taught me . . . she also got a university degree . . . I felt more confidence . . . better than listened to my friends or others . . . I felt a sense of security . . . because she got midwifery experiences. (Informant 9) Another mother shared, My child had a fever up to 40 degrees, and she was admitted to the hospital and received the antibiotics . . . she had urinary tract infection . . . the nurse [who delivered T-CBT] taught me how to take care of my child, and reminded me of the things I should pay attention to . . . the nurse got the professional knowledge . . . if others reminded me, I might not believe them . . . but a nurse, I felt a sense of security . . . more relieved. (Informant 5) Accessibility and flexibility of T-CBT. Some mothers (38.5%) found the T-CBT helpful because of its flexibility and accessibility to provide individualized and timely information. A mother said, It happened several times when I encountered problems in child care, I received phone calls from the nurse [who delivered T-CBT]. I immediately sough her advice . . . because it was not possible to go to the maternal and child center to ask the doctor . . . she could give me the professional advice which was helpful . . . I could also call back when I missed the call from the nurse. (Informant 21) Another mother echoed, I did not need to go out . . . I could ask the nurse on the phone about problems I encountered in childcare and my own recovery. (Informant 32) Theme 3: Barriers to T-CBT Effectiveness Barriers to the effectiveness of T-CBT were identified by the participants. These included difficult to meet individual needs and busy schedule of the mothers. Ngai and Chan 861 Difficult to meet individual needs. Although the majority of women (92.3%, n = 36) stated that the T-CBT was helpful, a few expressed that the information provided by the nurse at T-CBT could not satisfy their needs. A mother said, When I started to have breastfeeding, I asked the nurse [who delivered T-CBT] if I wanted to supplement with bottle feeding, how could I do it? . . . I also asked her other questions, but it seemed that she could not address my questions. (Informant 33) Busy schedule of mothers. Several mothers mentioned about their busy schedule and had missed the phone calls from the nurse who delivered T-CBT. A mother said, It was quite busy in particular for a first-time mother. The nurse had called me several times, but I was not able to listen to the phone calls. The nurse needed to keep calling me, and sometimes I had missed her calls. I knew it was the nurse’s call, but I was busy and unable to listen to her call. (Informant 14) Another mother said, I was really busy, sometimes I missed the nurse’s phone call and did not have the chance to talk to the nurse . . . when I tried to call back, the nurse was not on the phone or the line was busy. (Informant 28) Theme 4: Suggestions for Improving T-CBT Although one third of the mothers felt that the frequency and duration of T-CBT was sufficient, the majority of mothers suggested extending the T-CBT over a longer postnatal period. One woman said, Extending T-CBT over a longer period . . . 2-3 more weeks, eight sessions would be more appropriate in particular for first-time mothers, I looked forward to the nurse’s phone calls every week, and I would write down all my concerns . . . because when the nurse called me, I might not be able to remember all of them . . . so three more weeks would be better. (Informant 32) Some mothers suggested extending the T-CBT beyond the time when they returned to work. For example, a mother said, If the duration of T-CBT was longer, it could focus on more parenting issues which would be better . . . T-CBT was finished before I returned to my work. There might be many changes in childcare when I returned to work . . . how to 862 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) continue breastfeeding . . . how to use the breast pump . . . what’s the effect of decreased sucking from my child . . . and the emotional change . . . it would be better if T-CBT was longer, so that it could provide more support. (Informant 9) Another mother said, The frequency of T-CBT could be increased in the first two weeks because it was the most stressful time . . . 1-2 phone calls in the first two weeks, if there were not many problems, weekly at 4-6 weeks, then monthly up to six months . . . because the child might not be well developed at 3-month-old, the child might start to have the solid food at five months . . . learning to sit up. (Informant 3) Despite these suggestions, more than 92% (n = 36) of the participants expressed that they would recommend the T-CBT to other women, in particular the first-time mothers, because the T-CBT was useful in helping them cope with the demands of new parenthood. Discussion The findings of the qualitative data revealed that the majority of mothers found T-CBT helpful and enabled them to feel more skilled and confident in taking care of their child, less stressed, better emotional control, and more supported in taking up the maternal role. Existing literature suggested that new parents felt they had inadequate knowledge and skills in child care and experienced feelings of insecurity and incompetence in their parental role (Nilsson et al., 2015; Ong et al., 2014). Many mothers in this study found that it was the advice provided by the T-CBT nurse on the practical care of their child and dealing with common neonatal problems, that enabled them to feel more capable to cope and boosted their confidence in the maternal role. The findings concur with previous studies that the more a mother felt prepared for caring for her infant and equipped with the parenting skills, the greater her feelings of competence and fulfillment in the maternal role (Fowler et al., 2012; Gagnon & Sandall, 2011). Furthermore, new mothers in this study expressed that encouragement and verbal support from the T-CBT nurse helped reassure them and reinforced their confidence in their ability to perform parenting tasks. Verbal reassurance has been identified as an important source of building a woman’s competence for successful parenting (Bandura, 1989; de Montigny & Lacharite, 2004). In contemporary Hong Kong society, the breakdown of the extended family as a result of the rapid growth of the nuclear family, and the pressure of household tasks and employment have left many women feeling isolated Ngai and Chan 863 and incompetent in the maternal role (Ngai & Chan, 2012). In addition, with the decreasing length of stay in the hospital after childbirth, new mothers may not have enough time to learn parenting skills and acquire the experience necessary to develop competence with an infant (Nilsson et al., 2015). Thus, the T-CBT seems to provide new mothers with a valuable platform to acquire the knowledge and skills, and the professional support necessary to be competent mothers. The findings concur with previous studies that women expressed a need to be confirmed as competent mothers by health care professionals. This can be achieved by encouragement and confirmation that they are “doing it right” in caring for their child (Kynø et al., 2013; Persson, Fridlund, Kvist, & Dykes, 2011). The immediate postpartum period is often characterized by the mother’s great emotional lability and thus more vulnerable to the development of postnatal depression (Ngai & Ngu, 2015; Paulson & Bazemore, 2010). The skills taught at T-CBT including cognitive reframing and problem-solving strategies were identified as constructive and useful to the mothers in this study. Participants quoted examples of application of positive thinking and problem-solving skills to help them control their emotions when faced with the demands of infant care; thus, they tended to feel less stressed and have better emotions in the early postpartum weeks. The use of positive thinking and problem-solving skills may have helped mothers moderate their thoughts, feelings, and sensations that affect their daily activities and improve their effectiveness in managing negative emotions when faced with the demands of new parenthood. Findings from this study confirm the theoretical underpinning of T-CBT, which helps prevent postpartum depression through modifying negative thoughts and developing problem-solving skills (Sockol, 2015). Previous study has found that a telecare therapy teaching problemsolving and cognitive strategies was effective in reducing depressive symptoms in women suffering from postnatal depression (Ugarriza & Schmidt, 2006). This supports telephone-based intervention as a therapeutic option for promoting mental health during the postnatal period. Furthermore, emotional support through the T-CBT nurse was appreciated by the mothers in this study and regarded as an important positive component of T-CBT. It was observed that new mothers looked forwarded to the T-CBT nurse’s phone calls. Having the opportunity to talk about their feelings and being listened to seemed to make the new mothers less vulnerable to stress and more secure, in particular during the first month after delivery when they are confined to their homes due to the cultural practice of “doing-the-month.” Traditionally, Chinese mothers are recommended to practice the ritual of “doing-the-month” in which they are engaged in a series of month-long prescriptive and restrictive practices to restore their health, such as stay in the 864 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) house for a full month, do not wash hair and take shower to avoid exposure to cold wind (Holroyd, Lopez, & Chan, 2011). It was observed that the postpartum traditional custom of “doing-the-month” was still commonly practiced by contemporary Hong Kong Chinese women (Holroyd et al., 2011). Such practices may deter women from seeking perinatal services when they need help in child care or experience emotional distress. Thus, many mothers in this study appreciated the accessibility and flexibility of T-CBT to provide individualized and timely information. The effectiveness of T-CBT was further enhanced by the delivery of intervention with a nurse who could provide professional knowledge and expert advice on the parenting issues that new mothers encountered in the immediate postpartum period. Today, it is more easy and convenient for new parents to access parenting information with the availability of new media technologies. However, the exposure to profound information often creates confusion especially when it contradicts another. Porter and Ispa (2013) found that conflicting messages about childrearing could lead to confusion and stress. Thus, new mothers in this study appreciated the expert advice from a professional nurse who they could trust. The ability of T-CBT nurse to help new mothers solve the immediate problems they faced in parenting seemed to increase their sense of security. This was in line with previous studies that a mother’s sense of security during the early postpartum weeks depended on the level of support provided by the health care professionals and knowing where to seek help when needed (Persson et al., 2011). However, the busy schedule of new mothers and their individual needs seem to hinder the effectiveness of T-CBT. The early postpartum weeks are particularly stressful and busy for first-time mothers because of the daily demands of child care, such as breastfeeding (Ngai & Chan, 2012). Remedial measures, such as leaving T-CBT nurse’s contact number to call back when they were available and making more frequent calls at different time during the day, were introduced to enhance the accessibility and flexibility of T-CBT. However, some mothers still could not be reached. Alternative approaches of providing postnatal care, such as the instant mobile messaging or online forums, could be considered in addition to the telephone-based intervention to provide the new mothers with individualized information. Furthermore, many mothers expressed the concerns about continuing breastfeed after returning to work and needed more information about weaning and their child’s developmental needs. Extending the T-CBT for a longer postnatal period could be considered in the future development of perinatal care to provide ongoing support and information appropriate for the breastfeeding mothers and the changing developmental needs of the child. 865 Ngai and Chan Limitations This study was conducted with a small sample of Chinese first-time mothers participated in a randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of T-CBT, which might limit the transferability of the results. The sample comprised women who had completed all five sessions of the T-CBT, which may not be transferable to those who completed fewer sessions. Despite the limitation, it does provide in-depth and contextual data for a better understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of T-CBT, which is essential to improve the quality of care for first-time mothers. Conclusion The evidence suggests T-CBT as a feasible treatment modality with the potential to support mothers in managing the demands of the postpartum period. It is important to incorporate T-CBT into maternal and child health services on an ongoing basis, so that it can become part of the regular service and, therefore, readily accessible to all postpartum women to improve their perinatal well-being. Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank the research team in data collection and management. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund of the Hong Kong SAR Government. ORCID iD Fei Wan Ngai https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1760-5105 References Bandura, A. (1989). Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, 25, 729-735. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.729 Barlow, J., Smailagic, N., Huband, N., Roloff, V., & Bennett, C. (2014). Group-based parent training programmes for improving parental psychosocial health. Cochrane 866 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) Database of Systematic Reviews (5), Article CD002020. doi:10.1002/14651858. CD002020.pub4 Campbell, N. C., Murray, E., Darbyshire, J., Emery, J., Farmer, A., Griffiths, F., . . . Kinmonth, A. L. (2007). Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. British Medical Journal, 334(7591), 455-459. doi:10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE de Montigny, F., & Lacharité, C. (2004). Perceived parental efficacy: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(4), 387-396. doi.org/10.1111/j.13652648.2004.03302.x Dennis, C. L., & Chung-Lee, L. (2006). Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: A qualitative systematic review. Birth, 33, 323-331. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00130.x Fowler, C., Rossiter, C., Maddox, J., Dignam, D., Briggs, C., DeGuio, A. L., & Kookarkin, J. (2012). Parent satisfaction with early parenting residential services: A telephone interview study. Contemporary Nurse, 43, 64-72. doi:10.5172/ conu.2012.43.1.64 Gagnon, A. J., & Sandall, J. (2011). Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3), Article CD002869. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002869.pub2 Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105-112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 Holroyd, E., Lopez, V., & Chan, S. W. C. (2011). Negotiating “doing the month”: An ethnographic study examining the postnatal practices of two generations of Chinese women. Nursing & Health Sciences, 13, 47-52. doi:10.1111/j.14422018.2011.00575.x Kynø, N. M., Ravn, I. H., Lindemann, R., Smeby, N. A., Torgersen, A. M., & Gundersen, T. (2013). Parents of preterm-born children: Sources of stress and worry and experiences with an early intervention programme—A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 12, Article 28. doi:10.1186/1472-6955-12-28 Letourneau, N. L., Dennis, C. L., Cosic, N., & Linder, J. (2017). The effect of perinatal depression treatment for mothers on parenting and child development: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 34, 928-966. doi:10.1002/da.22687 Logsdon, M. C., Foltz, M. P., Stein, B., Usui, W., & Josephson, A. (2010). Adapting and testing telephone-based depression care management intervention for adolescent mothers. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13, 307-317. doi:10.1007/ s00737-009-0125-y Mohr, D. C., Ho, J., Duffecy, J., Reifler, D., Sokol, L., Burns, M. N., . . . Siddique, J. (2012). Effect of telephone-administered vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307, 2278-2285. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5588 Ngai, F. W., & Chan, S. W. C. (2012). Stress, maternal role competence, and satisfaction among Chinese women in the perinatal period. Research in Nursing & Health, 35, 30-39. doi:10.1002/nur.20464 Ngai and Chan 867 Ngai, F. W., & Ngu, S. F. (2013). Quality of life during the transition to parenthood in Hong Kong: A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 34, 157-162. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2013.852534 Ngai, F. W., & Ngu, S. F. (2015). Predictors of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms at postpartum. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78, 156-161. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.12.003 Ngai, F. W., Wong, P. W. C., Leung, K. Y., Chau, P. H., & Chung, K. F. (2015). The effect of telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy on postnatal depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84, 294-303. Nilsson, I., Danbjørg, D. B., Aagaard, H., Strandberg-Larsen, K., Clemensen, J., & Kronborg, H. (2015). Parental experiences of early postnatal discharge: A metasynthesis. Midwifery, 31, 926-934. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2015.07.004 Ong, S. F., Chan, W. C. S., Shorey, S., Chong, Y. S., Klainin-Yobas, P., & He, H. G. (2014). Postnatal experiences and support needs of first-time mothers in Singapore: A descriptive qualitative study. Midwifery, 30, 772-778. doi:10.1016/j. midw.2013.09.004 Paulson, J. F., & Bazemore, S. D. (2010). Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303, 1961-1969. Persson, E. K., Fridlund, B., Kvist, L. J., & Dykes, A.-K. (2011). Mothers’ sense of security in the first postnatal week: Interview study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 105-116. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05485.x Porter, N., & Ispa, J. M. (2013). Mothers’ online message board questions about parenting infants and toddlers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69, 559-568. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06030.x Raposa, E., Hammen, C., Brennan, P., & Najman, J. (2014). The long-term effects of maternal depression: Early childhood physical health as a pathway to offspring depression. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, 88-93. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.038 Sockol, L. E. (2015). A systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating and preventing perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 177, 7-21. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.052 Speziale, H. J. S., & Carpenter, D. R. (2011). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Ugarriza, D. N., & Schmidt, L. (2006). Telecare for women with postpartum depression. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 44, 37-45. Underwood, L., Waldie, K., D’Souza, S., Peterson, E. R., & Morton, S. (2016). A review of longitudinal studies on antenatal and postnatal depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19, 711-720. doi:10.1007/s00737-016-0629-1 Wisner, K. L., Sit, D. Y., McShea, M. C., Rizzo, D. M., Zoretich, R. A., Hughes, C. L., . . . Hanusa, B. H. (2013). Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 490-498. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87 868 Clinical Nursing Research 28(7) Author Biographies Fei Wan Ngai, Phd, is a registered midwife and received her PhD from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research interest is in the area of maternal health care, with special focus on the prevention of perinatal depression. Pui Sze Chan, MN, is a nurse midwife and has been working in obstetric nursing and prenatal diagnosis for over 10 years. Now she is a nurse educator and a clinical mentor of undergraduate students. She is interested in maternity nursing, especially on teenage pregnancy and related care; also on nursing education.