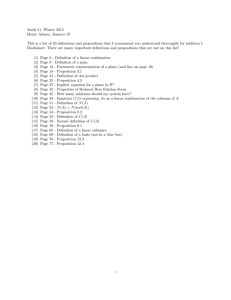

LEADERSHIP IN R&D PROJECTS 447 Leadership in R&D Projects Diana Grosse This article describes the results of an empirical study regarding a suitable style of R&D project leadership, especially what tasks project leaders should perform by themselves and what tasks they should delegate, what personal characteristics they should be endowed with and what kind of relationships they should have with their team. Fifty interviews were held in German institutions short-listed for an award for their innovative products by the Saxon government. In contrast to the assumption of the Social Identity Theory, in these institutions good R&D project leaders are not the ‘prototype’ of their team, but successfully balance the interests of the company and the R&D project team. Introduction A s Japanese automotive companies captured the European market in the 1970s, German managers began to search for the reasons that enabled the Japanese to drastically reduce the developmental period of a new vehicle, sometimes reducing the time by one and a half years. One of the reasons, according to a widely accredited study by Clark and Fujimoto (1991, p. 78), was that the Japanese create teams which are focused completely on the project task. In this way, the problem of employees’ prioritization of their respective departmental goals that arises in the German functional departmental organizations, was avoided in these Japanese firms. In addition, interface problems were hampering innovation in German institutions, such as the production department’s goal of cost reduction, which could hardly be reconciled with the goal of implementing new production methods, whereby one must test new methods even when these new methods induce higher costs. In order to overcome these interface problems, most organizations worldwide and also in Germany nowadays employ project management for R&D and product and process development tasks. Clark and Fujimoto (1991), and others before and after them, also highlighted their finding that the success or otherwise of the project depends critically on the project leader. They outline that what successful project leaders are composed of, if anything, is that they generally must be a heavyweight, i.e., © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing they can assert themselves within the organization (Clark & Fujimoto, 1991). In this article we first of all further define the attributes of (R&D) project leaders, leading to a number of propositions which were explored in the context of R&D projects in innovative German institutions. Theoretical Background The responsibilities of a leader include decision making, instruction and control, motivation, and the initiation of new assignments (Kosiol, 1976, p. 100 et seq.). These actions must be accomplished by a project leader, albeit within the scope of a project. Therefore, s/he must fulfill a task which is characterized by the following attributes: • time limit, • complexity, and • relative novelty (Corsten, 2000, p. 2). When dealing with the development of a new product, the attribute of interdisciplinarity must be added because employees from several different departments must work together. This requires a modification of the leadership functions. Instead of giving instructions, a project leader must integrate and work with the different team members. Motivation consists primarily of the willpower to overcome the barriers to innovation posed by the employees (Witte, 1988). An important function is the co-ordination of the project assignments in conjunction with the main products of the company. Volume 16 Number 4 2007 doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2007.00447.x CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT 448 Leadership Theories In the literature, three opinions differentiate the key characteristics of a successful leader: personality, leadership skills and relation to employees. Essentially, all three characteristics are of significance; however, during their scientific research, the scientists’ focus has changed several times. According to the Personalistic Approach, a leader distinguishes himself through very particular characteristics which differentiate him from the people he is leading. This approach has a long philosophical tradition: Plato already advocated the view that only a ruler with a wise personality could be the head of a state. Max Weber’s concept of a leader, who is equipped with the characteristic of charisma, plays a significant role. Due to his visionary dedication in conjunction with his visual judgement and the sense of responsibility, this leader surmounts the strong restraints of bureaucracy. According to past research traditions, these statements do not have any empirical foundation. In the following decades, numerous studies attempted to eliminate this disadvantage. In particular, after analysing 200 of these studies, Stogdill had ascertained that for a project to be successful a project leader should exhibit the following attributes (Wunderer & Grunwald, 1980): • • • • • aptitude and intelligence, performance and dedication, responsibility, sympathy, and status, socio-economical position Furthermore, studies also revealed that some of the employees also possessed the same characteristics. Hence, the notion was disproved that leaders can be identified based on their characteristics and that their characteristics differ from those of the employees. Furthermore, many different characteristics turned out to be lead to success depending on which concept of success was taken into account (Gebert, 2002). If the main purpose of the project is to generate a large profit, it is then necessary for the project leader to possess analytical-calculative skills. On the other hand, if the project is geared towards satisfying the employees, then the project leader must exhibit characteristics such as sympathy and to be able to make compromises. The measurement of success which is applied to the project arises from the situational context in which the project is embedded; this is the goal that the company has established. Due to the fact that the situational context varies with each project, each individual project requires a specific type of Volume 16 Number 4 2007 project leader who manages the project in his own specific way. These conclusions have been the basis for numerous elaborations in the field of leadership research (Nippa, 2006). The goal of these investigations was to identify a leadership style for every relevant situation that results in the successful outcome of each project. It was quickly realized that this plan was impractical. Therefore, further investigation was limited to two types of leadership styles: the task-oriented and the people-oriented leadership styles. Thereafter, researchers in the field of leadership styles tried to establish leadership styles that are suitable for certain situations. Moreover, the study by Fiedler (1967) is worth mentioning. He discovered that in situations with a very clear or with a vague task structure, a task-oriented leadership style provides the necessary goal orientation. Yet, the project leader can try to balance out the interests of all of the employees involved in the project in ambivalent situations, thus implementing a person-oriented leadership style (Fiedler, 1967). However, Fiedler also discovered that the choice of the appropriate leadership style depends not only on the structure of the tasks but also on the personalities of the employees. It is important not only what the project leader assigns but also how the employees interpret and implement these instructions (Rickards & Moger, 2006, p. 11). To list which attributes employees must possess is just as absurd as situation-oriented leadership styles, as the list would be endless. However, the approach of conceiving the behaviour as a result of the self-concept offers a possibility to produce a general characterization of employee attributes. According to the Self Categorizing Theory, people prefer actions which coincide with their self-concept as the sum of the cognitive representations that an individual has from within. The self-concept comprises three levels: • the self-assessment of one’s own personality, • the group to which one would like to belong, and • the awareness that one is a human being (Utz, 1999). In this context, the level of the reference group is relevant. If subordinates perceive the project team as a reference group, they will then contribute to the team and especially support the project team and their actions (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). To achieve the acceptance of each team member, the whole group situation, especially the leadership style of the project leader and the work atmosphere within the team, must allow each member to behave in accordance with his self-perception. © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing LEADERSHIP IN R&D PROJECTS 449 Situation Cognition Leader Behaviour Leader Cognition Team Behaviour Team Behaviour colleagues Cognition colleagues Success Figure 1. Leadership as an Interaction Between Leader and Employees A part of self-perception is or should be dedication; what you see as the purpose of your own life. Of course, a project leader cannot answer the question of the meaning of life. However, the Charismatic Leadership Theory requires the project leader to define the meaning of the project and to communicate its meaning to his employees. If successful in communicating the meaning, then the project leader is able to unleash unexpected innovative energy which results in more creative and happier employees (Gardner & Avolio, 1998; Berson & Linton, 2005). But a charismatic leadership style is always in danger of allowing the employees to develop too close a connection with the project leader, and, in particular, they might not be able to accept criticism. The project leader must guard against these tendencies of integration. The above depicted network that exists between the project leader and his/her employees is portrayed in Figure 1. Proposition Development Since the projects are to be executed within the company, they must fit into the organizational structure. Therefore, the job duties and the decisional competencies of the project leader and his employees must be predetermined. This occurs using the Transaction Cost Theory which states that the organizational structure must be shaped in such a way that the cost of the transactions – especially the information, co-ordination and the motivational costs – are minimal (Milgrom & Roberts, 1992, p. 29). The transactions which are analysed in this context are the transactions between the project leader and the team members. This approach is similar to the theory of transactional leadership (Burns, 1978). The difference between the two theoretical concepts is that the Transaction Cost Theory is more general. For instance, it is only assumed that employees maximize their utility whereas the transactional leadership theory allows for a closer look at the specific goals of the project leader © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing and the team members. As the disadvantage of being non-specific is balanced by the advantage of making recommendations about the organizational structure of a project, it was decided to state the propositions here in terms of Transaction Cost Theory. The Transaction Cost Theory implies situational factors such as uncertainty and opportunistic behaviour. This article makes allowance for these facts because it is dealing with R&D projects (uncertainty) and because it analyses incentives that are supposed to motivate the employees (the opportunistic effect is reduced because team members have signed an employment contract; see Baron & Kreps, 1999, p. 538). Moreover, it is assumed that organizational structures are influenced by the behaviour of the employees because they try to accomplish the role allocations that are implied by the structure elements. Consequently, seven propositions have been formulated about the behaviour of a successful project leader. These propositions describe the main elements of an organizational structure: job duties, decision-making authority, hierarchical rank and communicative relations. (Rickards and Moger identify this as an important aspect of leadership, Rickards & Moger, 2006, p. 5.) According to Adam Smith, productivity can be increased if a task is split into sub-tasks and, thereafter, given to several employees who will be able to realize the effects of learning. These sub-tasks can be divided into managing and executing sub-tasks within a project. The managing of sub-tasks should be taken over by the project leader. The newer the project, the more difficult the prediction of success. Therefore, the results can only be rated and controlled by a leader who can evaluate the working processes because they are involved in the R&D process. This leads to the first proposition: Proposition 1a: Successful R&D project leaders carry out decision-making, instructing, controlling, and initiating tasks and, additionally, actively participate in the project. Volume 16 Number 4 2007 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT 450 Similarly, the employees need to overcome the principle of specialization. Due to the novelty of the project, unexpected outcomes will occur. Hence, close communication and co-operation among all employees is essential. This leads to: Proposition 1b: Successful R&D project organizations combine project members into one team which is characterized by overlapping fields of responsibilities and a common interest identity (Högl & Gemünden, 1999; Amason, 1996). After the job duties are defined, the next proposition deals with the degree of decisionmaking authority. Proposition 2: In the case of a dynamic environment and highly motivated employees, successful R&D project leaders delegate tasks to the employees who are most competent. Highly qualified employees will produce lower costs for information acquisition. The cost reduction will be significant enough to compensate for the costs of delegating the decision-making authority to the employees. In a dynamic environment, the data that need to be acquired are constantly changing. Laux has mathematically proven this correlation (Laux & Liermann, 1990; McGrath, 2001). The delegation of decision-making authority proves to be beneficial for R&D projects. The dynamic of R&D projects allows the organizational rules to become obsolete. Thus, the company needs employees who are capable of acting independently and without fixed rules. According to Allport, these capabilities, or attributes, provide people with the ability to process stimuli from the environment in such a way to derive consistent actions from them (Heckhausen, 1989, p. 39). Proposition 3 describes the attributes which the selfdetermined employees, especially a project leader, should have, in order to manage the project tasks efficiently. Proposition 3: Successful R&D project leaders possess the following features: • knowledge • creativity • experience • self-confidence, a positive self-concept • risk tolerance, ability to manage conflicts • commitment, intrinsic motivation for performance • ability to assert oneself • sympathy • sense of responsibility. These attributes result from transferring Stogdill’s leadership characteristics into the Volume 16 Number 4 2007 situation of a complex project and also from evaluation of other empirical studies (Judge et al., 1999; Sternberg et al., 2004). Their theoretical foundation is the following: information and control costs can be reduced if project leaders have expert knowledge. They are better able to motivate their employees if they themselves are dedicated and capable of tolerating uncertainty. In particular, co-ordination costs can be saved in a matrix organization if the project leader can be assertive amongst the other department leaders. Proposition 4: Successful R&D project leaders use the leadership style of ‘management by objectives’. The goals are determined in co-operation with the employees at the beginning of the project. Since they can use their specific knowledge to their benefit, project leaders can save on informational costs. The employee can choose his way to individual success. This will increase the motivation of scientists who like to work independently. A delegation of decision competencies is connected to some risks. The project leader has the risk that the employee will follow their own personal goals rather than the goals of the company while working, but also the employee has the risk of failure. Additionally, the employee does not know about their boss’s loyalty in the event of a disappointment. According to the Principal Agent Theory, the first risk can be reduced if the employee takes a share in the project’s success. Thus, their own interests are connected to the goals of the organization. The second risk will be lower if the team members have already gained experience in previous situations in which the project leader has supported them. Proposition 5: Motivational costs can be saved when the employee is given incentives; thus, allowing them to be able to satisfy Maslow’s postulated needs of provision of goods, safety, sense of community, appreciation, and self-actualization with their project task. The next proposition deals with the longing for support, which can be derived from several Maslovian needs. Support of the superior is shown by understanding when the results, over the course of the project, turn out to be different from those originally planned. Instead of punishing the employees, the superior changes the plans and implements new guidelines (Hauschildt, 1997, chapter 11). In this regard, a continuous process control is necessary not only for motivational reasons but also because of cost efficiency. The production of a product that the market does not © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing LEADERSHIP IN R&D PROJECTS accept, which would create large losses, can be impeded by a constant acclimatization of the project plan to reality. Proposition 6: Co-ordination costs as well as motivational costs can be saved when a continuous process control rather than a rigid result control is conducted, by which final results are demanded. These are sometimes difficult to achieve, especially in innovative projects. Team members, who may explain deviations from planned data as in a continuous process control, feel more self-assured. Hoog and Haslam expand the idea that the project team becomes an identification group for its members when it corresponds to their own self-concept to a Social Identification Theory of Leadership. Initially, they establish the specifics of the composition of a group. A professional tennis club can become the identification group for an ambitious tennis player because many other ambitious players are also mmbers, and, therefore, dedication for sports is a typical member characteristic. Furthermore, they state that if the project leader fits this prototype, then the team members will willingly follow him because they can identify with him (Haslam, 2001; Hoog, 2001). Proposition 7: The employees will identify with the project leader when s/he prototypically expresses the behaviour of her/his team, especially their self-concept. This alleviates her/him from the execution of his/ her leadership functions and, additionally, reduces the leadership costs. 451 Table 1. Project Success Criteria of Success Exceeding the planned time Exceeding the planned costs Economic expectations fulfilled Technical expectations fulfilled Average 1 yes 4,5 6 no 1 yes 5 6 no 1 yes 4 6 no 1 yes 4 6 no p. 16). We analysed the data of the supervisors because they seemed to be more objective, supervisors having a better overview of the projects. The supervisors were asked to rate the leadership skills of an R&D project leader for a specific project because the ability to remembering is better if you have to remember a particular incident. If their ratings correspond with our propositions and if the project was assessed as being successful, then this can be considered as an indication of the validity of the propositions. If the necessary data were available, regression analyses have also been conducted. Results Methodology Project Success To test these propositions, 50 semi-structured interviews were conducted at institutions throughout Germany between the period of September 2002 and March 2003. These are institutions that have been short-listed for an award for their innovative products by the Saxon government. This ensured that R&D projects were being actively conducted there. As the projects were rather small, the team size was small too: 5–15 members. The supervisors of the project leaders, i.e. a member from the steering committee, and the team members were interviewed. But the project leaders were not questioned in order to avoid possible self-delusion. The validity of the results was checked by comparing the answers of the two groups. There were only slight deviations between the two groups and, therefore, it is sufficient with regard to validity to interpret the results from only one group (Schuler, 1995, The projects that the interviews are based on can, on average, be classified as successful in the sense that they essentially implemented the guidelines of the plan (see Table 1). © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Job Duties and Delegation of Tasks (Propositions 1, 2) All projects were executed in teams, which were presided over by the project leader. This project leader would also assign developmental tasks. Therefore, Propositions 1a and 1b can be considered valid. In order to determine the distribution of the decision-making authorities, we asked who had to make the final decision, the project leader or a team member. Of course, close communication has to precede each decision (for the list of the tasks, see de Pay (1995), p. 61). The answers are shown in Table 2. Volume 16 Number 4 2007 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT 452 Table 2. Delegation of the Project Decision-Making Authority PL 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. TM Feasibility study for the project Conclusion of a contract for external projects Practical implementation and definitions of the project Co-ordinated determination of the connection of the project on the line organization Planning of the project goals Planning of the time Planning of the costs Recruitment of the employees Acknowledgement of the incentives for the employees Searching for ideas Evaluation of the ideas Creation of the concept Decision: stop or go Creation of the prototype Acceptance of the prototype Handing over to production Project control Take responsibility for the project in the communication with external authorities Final invoice Documentation PL = project leader, TM = team member. Volume 16 Most of the decisions are made solely by the project leader. In contrast, the employees may decide which ideas they choose to follow, how they proceed with the creation of the prototype, and, ultimately, how they match their concept with the requirements of the series production during the developmental work, and which results they document. Proposition 2 can be considered valid because employees were dealing with tasks for which they had better knowledge. Table 3. Effect of Characteristics (Dependent Variable: Efficiency) Leadership Skills (Proposition 3) Note: level of significance: ** 0.05, * 0.10. The assumption about leadership skills has been verified on two levels: does a project leader have to have special characteristics, and if so, what kind of characteristics? Most of the interviewees agreed that there are leadership qualities and that they are important. Whether these statements are valid was proven by regression analysis. The results show that there is a positive linear correlation between the variables ‘efficiency’ (planned data are fulfilled, see Table 1) and ‘leadership characteristics’. Obviously, projects led by project leaders with the appropriate attributes could maintain their planned data. This correlation is significant (see Table 3). In Table 4 these qualities are listed according to their rank of importance. It is apparently more important for a project leader to understand the project in detail than to possess all of the leadership qualities. The reason is the Number 4 2007 Independent variable Specification Constant Characteristics R2 = 4.9 F-value = 3.52 No. of investigations: 48 4.2** 0.2* © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing LEADERSHIP IN R&D PROJECTS 453 Table 4. Leadership Qualities Table 5. Management by Objectives (Dependent Variable: Efficiency) (MbO) Rank Independent variable Knowledge Creativity Commitment; intrinsic motivation Risk-tolerance, ability to manage conflicts Sense of responsibility Sympathy Self-confidence, positive self-concept Ability to assert oneself in communication with supervisor Experience 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 novelty of the project. Given the fact that one cannot fall back on experience as with a routine project, the supervision should be conducted by an expert. A survey of 215 companies with project management, conducted by Keim (1997), confirmed that it is very important for a project leader to show technical and managerial capabilities (Keim, 1997, p. 263). The fact that the characteristic of sympathy was assigned a lower rank is related to the fact that the interviewees assumed the granting of incentives to be more important than showing sympathy. These incentives were closely connected to the success of the project (see Table 6), ensuring that the team members worked hard to reach the project goals. As most companies preferred the leadership style of management by objectives, negotiations about and controlling of these project goals were important management devices. Specification Constant MbO R2 = 3.74 F-value = 3.10 No. of investigations: 54 3.5** 0.2* Note: level of significance: ** 0.05, * 0.10. Measures of Incentives (Proposition 5) The statement that the employees are further motivated when they can implement personal goals within the project was tested through two questions. 1. Are agreements made with the employees about the goals that they can personally realize by working on the project? In 90 percent of the cases there are such ‘goal agreements’. 2. Are the listed measures of incentives in Table 6 given, and which meaning will be attributed to them? Thus, these incentives are set by the companies which satisfy every level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – except for a flexible work schedule. This results from the fact that the projects are conducted by firms. Their projects have to fit in the product portfolio of the company. Therefore, the R&D employees do not have much flexibility either in regard to their R&D topics or their working hours. Process Control (Proposition 6) Management by Objectives (Proposition 4) All R&D project leaders execute the leadership style of ‘management by objectives’. They attach a great meaning to the definition of goals in accordance with the employees – both project goals as well as personal goals. Thereafter, these goals are independently pursued by each team member. These statements could be proven by a regression analysis. As shown in Table 5, there is a significant linear correlation between the independent variable ‘leadership style: management by objectives (MbO)’ and the dependent variable ‘efficiency’ (MbO is measured on a scale from 1 = no to 6 = yes). Thus Proposition 4 is confirmed. © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing An open-ended question was posed to find out how the control is conducted. The interpretation of heterogeneous answers shows that a process control is normally performed which is conducted as follows. At certain points in time – for the most part at the beginning of the week – the sub-tasks are determined and distributed to the employees. In periodical, short phases the project leader checks on their accomplishment. In this way, the project leader always maintains a close eye on the achievement of further specified milestone results. The project leader uses their specialized knowledge for a contextual examination. Would they have done it the same way? Interesting but not urgent questions are saved in a dataset to be analysed as soon as time permits. Volume 16 Number 4 2007 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT 454 Table 6. Measurement of Incentives for the Employees Category Personal development Tangible incentives Social status Flexibility Measures Relevance (average) – Presentation on the project – Advanced training 1 2 3 4 5 6 irrelevant relevant – Interest – Bonus for a successful project – Salary increase 1 2 3 4 5 6 irrelevant relevant – Promotion – Recognition – Permanent contract 1 2 3 4 5 6 irrelevant relevant – Flexible work schedule – Time for personal research 1 2 3 4 5 6 irrelevant relevant Table 7. Group Identification (GI) (Dependent Variable: Efficiency) Independent variable Constant GI p-value No. of investigations: 49 Specification 0 -0.001 0.99 If necessary, the planning data are adjusted to the altered requirements. they must be assertive amongst the management and the customers, they also have to consider their goals. It is therefore required that they are able to maintain a balance of the interests among all three groups. Neither for their own interest, nor for the company’s interest, can they solely follow their employees’ wishes (Mumford et al., 2002, p. 738: he writes that a leader must play multiple roles). 2. If project leaders and the group are too close, the phenomenon ‘group think’ might occur. The group might no longer be open to proposals nor criticism. The quality of the project will go down which is damaging to the interests of the company (Schulz-Hardt, 1997). Prototypical Leader (Proposition 7) The assumption of a prototypical project leader was tested by the question: ‘How strong should each team member identify with his project leader?’ (Group identification). Later, the correlation between these answers and the dependent variable ‘efficiency’ was investigated through a regression analysis. As can be seen in Table 7, there is no significant correlation between these two variables. These calculations are not sufficient to disprove the thesis of the ‘prototypical project leader’. However, two arguments tend to imply the opposite: 1. Project leaders are not only interested in realizing the wishes of their employees. As Volume 16 Number 4 2007 How can this danger of too close an integration, which is high according to the statements of the interviewees, be removed? Some possibilities are suggested in Figure 2. On the one hand, Ollila’s advice should be adopted. A project leader should take some time to reflect on their leadership style and the group processes (Ollila, 2000). On the other hand, they should implement actions such as gatekeepers, control measures and substituting team members. The last measure is not considered to be beneficial by the interviewees, probably because of a loss of specialized knowledge. In summary, one can characterize the relationship between the project leader and their © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing LEADERSHIP IN R&D PROJECTS 455 Unfortunately, no statements can be made regarding the charismatic leadership style because the interviewees did not consider this leadership style to be appropriate for their projects which only had a low level of novelty. Therefore, future research needs to be conducted on this leadership style, especially on the relationships between charismatic and transactional leadership styles. The leader– employees relationship should also be further analysed. Relevance 4,5 4 3,5 3 2,5 2 1,5 1 0,5 0 a b c d Indication Key: a = Risk of groupthink b = Control through external instances c = Substitution of team members d = Gatekeeper Figure 2. Instruments Against Groupthink employees as follows: project leaders must be accepted as the leader by their employees. According to Heider’s Attribution Theory, the prerequisites for acceptance are that project leaders shows capability and commitment (Heckhausen, 1989, pp. 397f). Conversely, it is not necessary that they prototypically reflect the self-concept of the employees. Conclusion Based on the empirical surveys, six out of seven propositions seem to hold in the German institutions where our empirical data were gathered. Confirming the recent literature, a successful R&D project leader has the following profile: s/he should possess leadership qualities; in addition to the leadership functions, s/he should contribute to the project; s/he should lead by means of ‘management by objectives’; leave the decisions of the projects in which the employees have more of an understanding to the employees; continuously control the completion of the tasks; provide incentives for the project; and s/he should obtain acceptance as the project leader from the employees through commitment and specialized knowledge. Based on these findings management can be recommended to: • carefully recruit R&D project leaders making sure that they possess the necessary attributes, and • give each project leader the freedom to determine the project structure. © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing References Amason, A.C. (1996) Distinguishing the Effects of Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict on Strategic Decision Making. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 123–48. Baron, J. and Kreps, D. (1999) Strategic Human Resources. John Wiley, New York. Berson, Y. and Linton, J. (2005) An Examination of the Relationship Style, Quality and Employee Satisfaction in R&D Versus Administrative Environments. R&D Management, 35, 51–60. Burns, J.M. (1978) Leadership. Harper & Row, New York. Clark, K. and Fujimoto, T. (1991) Product Development Performance. Harvard Business School Pr., Boston, MA. Corsten, H. (2000) Projektmanagement. Oldenbourg, Munich. Fiedler, F. (1967) A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness. McGraw-Hill, New York. Gardner, W. and Avolio, B. (1998) The Charismatic Relationship: A Dramaturgical Perspective. Academy of Management Review, 23, 32–58. Gebert, D. (2002) Führung and Innovation. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. Haslam, S.A. (2001) Psychology in Organizations. Sage Publications, London. Hauschildt, J. (1997) Innovationsmanagement. Vahlen, Munich. Heckhausen, H. (1989) Motivation and Handeln. Springer, Berlin. Högl, M. and Gemünden, H.G. (1999) Determinanten and Wirkungen der Teamarbeit. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft – Ergänzungsheft, 2, 35–59. Hoog, M.A. (2001) A Social Identity Theory of Leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5, 184–200. Judge, T.A., Thoresen, C.J., Pucik, V. and Welbourne, T. M. (1999) Managerial Coping with Organizational Change: A Dispositional Perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 35–59. Keim, G. (1997) Projektleiter in der industriellen Forschung und Entwicklung. Gabler, Wiesbaden. Kosiol, E. (1976) Organisation der Unternehmung. Gabler, Wiesbaden. Laux, H. and Liermann, Z. (1990) Grundlagen der Organisation. Springer, Berlin. McGrath, R. (2001) Exploratory Learning, Innovative Capacity and Managerial Oversight. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 118–31. Volume 16 Number 4 2007 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT 456 Milgrom, R. and Roberts, J. (1992) Economics, Organisation and Management. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Mumford, M.D., Scott, C.M., Gaddis, B. and Strange, J.M. (2002) Leading Creative People: Orchestrating Expertise and Relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 705–50. Nippa, M. (2006) Lessons from the Search for the Perfect R&D Leader. On the Need to Turn Away from Adding to a Patchwork of Loosely Coupled Insights to Distinct Research Agendas. Paper presented at the 66th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Atlanta, USA, August. Ollila, S. (2000) Creativity and Innovativeness through Reflective Project Leadership. Creativity and Innovation Management, 9, 195–200. de Pay, D. (1995) Informationsmanagement von Innovationen. Gabler, Wiesbaden. Rickards, T. and Moger, S. (2006) Creative Leaders: A Decade of Contributions from Creativity and Innovation Management Journal. Creativity and Innovation Management, 15, 4–18. Schuler, H., Funke, U., Moser, K. and Donat, K. (1995) Personalauswahl in Forschung und Entwicklung. Hogrefe, Göttingen. Schulz-Hardt, S. (1997) Realitätsflucht in Entscheidungsprozessen von Groupthink zu Entscheidungsautismus. Huber, Bern. Volume 16 Number 4 2007 Sternberg, R., Kaufman, J. and Pretz, J. (2004) A Propulsion Model of Creative Leadership. Creativity and Innovation Management, 13, 145–53. Utz, S. (1999) Soziale Identifikation mit virtuellen Gemeinschaften. Pabst, Berlin. Tajfel, H. and Turner, J.C. (1979) An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In Austin, W.G. and Worchel, S. (eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks/Cole, Monterey, pp. 33–47. Witte, E. (1988) Innovationsfähige Organisation. In Witte, E., Hauschildt, J. and Grün, O. (eds.), Innovative Entscheidungsprozesse. J.C.B. Mohr, Tübingen, pp. 144–61. Wunderer, R. and Grunwald, W. (1980) Führungslehre, Vol. I. de Gruyter, Berlin. Diana Grosse (diana.grosse@bwl.tufreiberg.de) is a professor of Business Administration at the Technical University of Freiberg. Her research area is the organization of routine and innovation projects; her theoretical basis is institutional economics. © 2007 The Author Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing