Chicano Art & Identity: Thesis on Mexican-Americans (1968-1992)

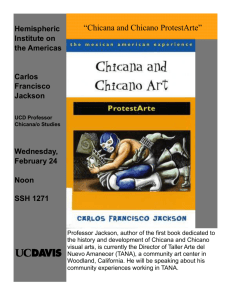

advertisement