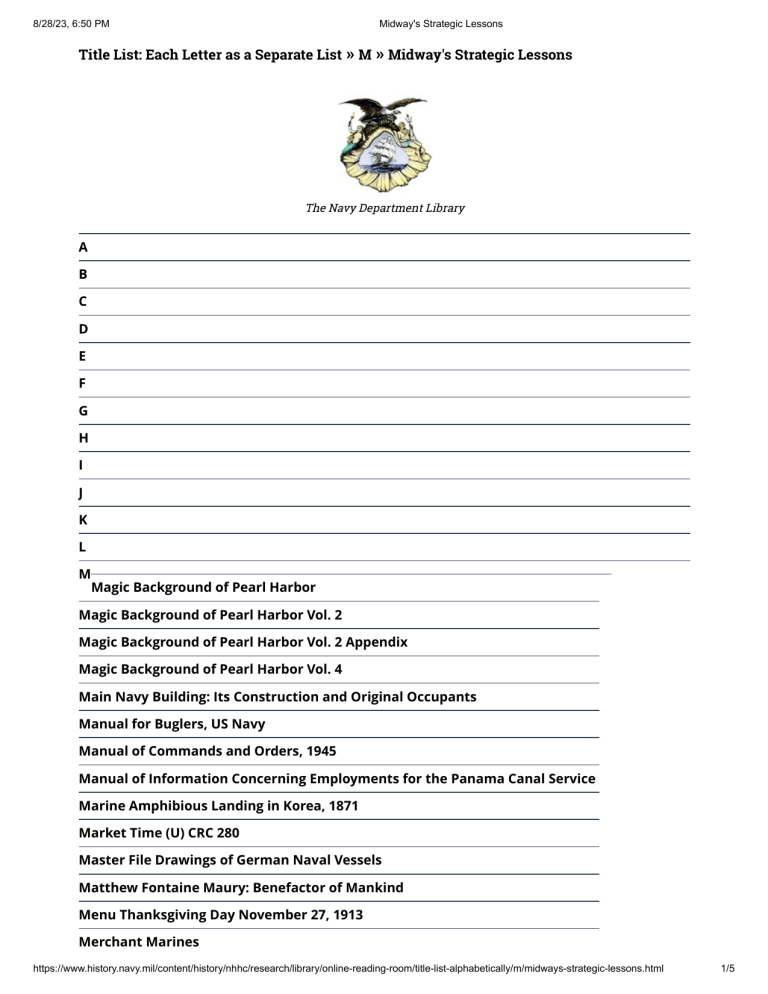

8/28/23, 6:50 PM Midway's Strategic Lessons Title List: Each Letter as a Separate List » M » Midway's Strategic Lessons The Navy Department Library A B C D E F G H I J K L M Magic Background of Pearl Harbor Magic Background of Pearl Harbor Vol. 2 Magic Background of Pearl Harbor Vol. 2 Appendix Magic Background of Pearl Harbor Vol. 4 Main Navy Building: Its Construction and Original Occupants Manual for Buglers, US Navy Manual of Commands and Orders, 1945 Manual of Information Concerning Employments for the Panama Canal Service Marine Amphibious Landing in Korea, 1871 Market Time (U) CRC 280 Master File Drawings of German Naval Vessels Matthew Fontaine Maury: Benefactor of Mankind Menu Thanksgiving Day November 27, 1913 Merchant Marines https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/m/midways-strategic-lessons.html 1/5 8/28/23, 6:50 PM Midway's Strategic Lessons Merchant Ship Shapes Mers-el-Kebir Port Instructions for Merchant Vessels [1942] Mess Night Manual Midway in Retrospect: The Still Under Appreciated Victory Midway’s Operational Lesson: The Need For More Carriers Midway: Sheer Luck or Better Doctrine? Midway's Strategic Lessons Midway Plan of the Day Notes Military Sealift Command Military Service Records and Unit Histories Mine Sweeping Manual 1917 Mine Warfare Mine Warfare in South Vietnam Miracle Harbor Miscellaneous Actions in the South Pacific More Bang for the Buck: U.S. Nuclear Strategy and Missile Development 19451965 My days aboard U.S.S. Santa Fe N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Tags Midway Related Content https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/m/midways-strategic-lessons.html 2/5 8/28/23, 6:50 PM Midway's Strategic Lessons Topic Document Type Publication Wars & Conflicts World War II 1939-1945 Navy Communities File Formats Location of Archival Materials Author Name Place of Event Recipient Name Midway's Strategic Lessons “We are actively preparing to greet our expected visitors with the kind of reception they deserve,” Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, wrote to Admiral Ernest J. King, the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, on 29 May 1942, “and we will do the best we can with what we have.” How did Admiral Nimitz plan to fight the Battle of Midway? His opposing fleet commander, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, Commander in Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet, had formulated his strategy for Operation MI, the reduction of Midway to entice Nimitz to expose his few aircraft carriers to destruction. The Japanese plan proved incredibly complex. When one compares the convoluted nature of Yamamoto’s plan to Nimitz’s, the latter emerges as simple and economical. Aware of the nature of the Japanese operation that ranged from the Aleutians to Midway, and involved aircraft carriers in both areas, Nimitz concentrated his forces at the most critical location, poised to attack the enemy when long-range flying boats operating from Midway would locate him. The actual sighting of the Japanese on 3 June, heading for Midway, vindicated Nimitz’s trust in the intelligence information he possessed, information that had been vital to the formulation of his strategy. Yamamoto, by contrast, could only hazard a guess where his opponent was: the American placement of ships at French Frigate Shoals and other islets in the Hawaiian chain, in addition to a swift exit of carrier task forces (Task Force 16 under Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance and Task Force 17 under Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher) from Pearl Harbor, meant that (1) Japanese submarine-supported flying boat reconnaissance could not originate at French Frigate Shoals and (2) the submarines deployed to watch for American sorties arrived on station too late. Knowing Japanese intentions and the forces involved, Nimitz maintained the emphasis on the central Pacific, and sent cursory forces, sans aircraft carriers, to the Aleutians. The Pacific Fleet’s battleships, on the west coast of the United States, played no role in the drama, because Nimitz’s primary goal was the same of his opponent: sink the enemy aircraft carriers. While the Japanese hoped to draw the U.S. carriers, that had https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/m/midways-strategic-lessons.html 3/5 8/28/23, 6:50 PM Midway's Strategic Lessons operated out of range through most of early 1942, so too Nimitz desired to bring the Japanese carriers, that had operated in much the same fashion from Pearl Harbor through the Indian Ocean (and thus well beyond reach) to the same end: destruction. Nimitz’s strategy was direct and to the point; the Japanese’ involved operations that were to divert American strength from the main battle. Nimitz’s knowledge of the Japanese intentions and deployment of forces, however, meant that he had no need to employ diversions to keep the enemy guessing. Nimitz knew where the enemy was to be and employed what forces he had to be there to meet him; he had faith in his commanders: Fletcher, victor of Coral Sea, enjoyed his confidence, and Spruance had come highly recommended by Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., his commander during the early eastern Pacific raids. When Lt.Col. Harold F. Shannon,. USMC, commanding the USMC garrison at Midway, declared he would hold Midway, Nimitz sent him what reinforcements he could, and provided them to Comdr. Cyril T. Simard, who commanded the overall defense forces at Midway. Popular legend has made much of the Japanese having four carriers and the U.S. Navy three. Midway itself proved to be the equalizer, serving as base for long-ranged aircraft that could not be taken to sea – four-engined heavy bombers (B-17) and flying boats in sufficient quantity for reconnaissance and attack. Nimitz gave Midway “all the strengthening it could take,” exigencies of war dictating the numbers and types of planes employed. Additionally, Admiral Yamamoto opted to go to sea to exercise direct control over Operation MI, embarking in the battleship Yamato. Admiral Nimitz, by contrast, exercised what control he did from Pearl Harbor, from his shore headquarters at the Submarine Base. Nimitz quite rightly chose to exercise command and control from an unsinkable flagship, and boasted far better communication and intelligence facilities than one could find at sea. Such an idea was, however, not novel; his predecessor, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, had moved his headquarters ashore in the spring of 1941, as had Admiral Thomas C. Hart, Commander in Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, at Manila, P.I., around the same time. Nimitz clearly possessed tremendous faith in his subordinates, who were nevertheless guided by very clear instructions. His principle of calculated risk is, perhaps, his most brilliant contribution to the battle, in that it precisely and economically conveyed his intentions to his task force commanders. There was no doubt about what they were supposed to do, how they were supposed to do it, and what level of risk was acceptable. Nimitz’s operations plan for the defense of Midway is a model for effective macromanagement, spelling out essential tasks in general terms, with a minimum of detail-specific requirements. Nimitz’s plan for the Battle of Midway avoided long-range micro-management and allowed the commanders on the battlefield to make key operational and tactical decisions. One can contrast the simplicity of Nimitz’s OpPlan with the voluminous orders Yamamoto produced prior to the battle, many of which served little purpose in the final analysis. Nimitz, arguably a better strategist, possessed a clear vision of what he wanted to do – basically, to bring the Kido Butai to battle and to destroy it -- and he clearly communicated those intentions to his operational commanders. Good strategy, however, is useless without quality operational commanders who thoroughly understand the plan and are able to put that strategy into action. Although Naval War College analysts believed that plans needed to be formed in light of enemy capabilities and not intentions, something for which they castigated Yamamoto, Admiral Nimitz’s battle planning benefited enormously from having a very good notion of enemy intentions derived from excellent radio- https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/m/midways-strategic-lessons.html 4/5 8/28/23, 6:50 PM Midway's Strategic Lessons intelligence. Such precise and economic employment of forces could not have occurred unless he possessed the ability to gather strategic intelligence on the enemy. Indeed, one can argue that the battle would never have taken place at all had Japanese intentions been cloaked in mystery. Nimitz’s active preparations for the Battle of Midway indeed provided a momentous reception for the enemy, and once he had issued his operations orders, he entrusted the fighting of the battle to subordinates. Knowing your enemy is coming is one thing, but meeting him on the battlefield and defeating him, is altogether another. In the actions of 4-6 June 1942, those subordinates, from flag officer to fighter pilot, more than justified his faith in them. They had written, Nimitz declared afterward, “a glorious page in our history.” [END] Published: Mon Nov 13 09:16:18 EST 2017 NHHC | Research | Our Collections | Visit Our Museums Browse by Topic | News & Events | Get Involved | About Us Accessibility/Section 508 | Employee Login | FOIA | NHHC IG | Privacy | Webmaster | Navy.mil | Navy Recruiting | Careers | USA.gov | USA Jobs No Fear Act | Site Map | This is an official U.S. Navy web site https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/m/midways-strategic-lessons.html 5/5