SMEs' eBusiness Readiness in Singapore: A Research Paper

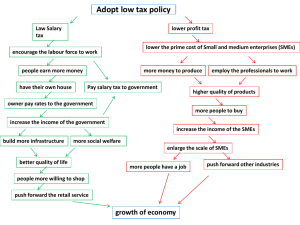

advertisement

RANGSIT JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, VOL. 1, NO. 1, JANUARY-JUNE 2013 17 Observations on SMEs’ eBusiness Readiness: Singaporean Restaurants in Tanjong Pagar Suttisak Jantavongso Abstract—This paper reports findings from the qualitative study conducted in Tanjong Pagar, Singapore, to determine the state of electronic business (eBusiness) readiness by small to medium enterprises (SMEs). This paper is one of series of working papers on an eBusiness deployment framework (EBDF) for Thai SMEs by the author. The author is actively refining key factors that contribute to a successful adoption of eBusiness in Thailand since 2002. In 2003, the author published a new age eBusiness model targeting at SMEs in developing countries [1]. This was followed by the study of eBusiness Adoption Focusing on Thai SMEs in 2006 [2]. Following these studies, the EBDF for Thai SMEs was successfully developed and statistically validated in 2007 and 2013, respectively. While the studies were targeting at the SMEs in Thailand, the author has always envisaged that the EBDF is applicable to SMEs operating in other countries with some contextual modification. Therefore, it was expected that SMEs operating overseas were able to take advantages of the EBDF in their eBusiness implementations. Three restaurants classified as SMEs in Tanjong Pagar were selected. This paper presents a discussion on the findings. The aim of the paper is not to re-introduce the full details of the EBDF, but to state the eBusiness readiness of Singaporean SMEs and see whether the EBDF would fit their engagements in eBusiness. A mixed research approach was employed involving observations, indepth interviews, and document reviews to gather relevant data. The observations took place in March 2013 at the participants’ premises. The initial findings are aligned with the author’s existing studies and show that the EBDF is applicable to support the Singaporean SMEs’ eBusiness initiative. Index Terms—Electronic business deployment framework (EBDF), electronic business (eBusiness) readiness, small to medium enterprise (SME), SME enterprise software. I. INTRODUCTION S MALL to medium enterprises (SMEs) are considered key contributors to the economic development of most countries. SMEs comprise of the majority of enterprises worldwide. The importance of SMEs as a prime generator of economic activity is confirmed in the statistics provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Within the 34 nations comprising the OECD, SMEs account for approximately 95 percent of the total number of enterprises, and provide more than 50 percent of the private sector employment within the region [3]. A similar picture also The author is with the Faculty of Information Technology, Rangsit University, Pathumthani 12000, Thailand (e-mail: suttisak.j@ rsu.ac.th). Fig. 1. Location map of Tanjong Pargar [5]. emerges in other regions, and of interest in the context of this study is Singapore which is a member of the Asian Economic Community (AEC). Accordingly, SMEs in Singapore are also the lubricant of its economy without which Singapore economy may not thrive. There are approximately 148,000 SMEs in Singapore, contributing almost 99 percent of all enterprises. SMEs contribute more than 45 percent to Singapore’s gross domestic product (GDP), and employ more than 60 percent of the workforce [4]. Singapore is selected as the country under study for this research as the Singapore government has declared interest in promoting and supporting SMEs. On the other hand, Tanjong Pagar district is an economic center of Singapore. It is also a historic district located within the Central Business District (CBD), see Fig. 1. Tanjong Pagar has been promoted as an authentic representation of Singapore [6]. It represents the efforts of the Singapore government in promoting Singapore’s built heritage, in particular the architectural details of shophouses to ensure authenticity [6, Chapter 14]. Nearly 80 percent of the activities within Tanjong Pagar are restaurants, retail outlets, offices, pubs, lounges, and hotels. Three foci of the study are presented in this paper. The first is to study background of restaurants in Tanjong Pager. The second is to study current circumstances and problems of restaurants in Tanjong Pagar. The third is to assess the eBusiness readiness of restaurants in Tanjong Pagar based on the finding of the first two foci. © 2013 RANGSIT UNIVERSITY 18 RANGSIT JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, VOL. 1, NO. 1, JANUARY-JUNE 2013 II. LITERATURE REVIEW eBusiness A. Definition of SMEs in Singapore The natural starting point in defining an SME is an overview of the ways in which an SME differs from a large enterprise. Identifying and distinguishing SMEs is not an easy matter, and there is no single definition of an SME. Definitions of SMEs also vary across countries, and depend on the selected parameters and the extent of economic contribution [7]. Despite this, SMEs in Singapore can be defined as having: (1) at least 30 percent of their local equity being held by Singaporeans or Singapore’s permanent residents (PRs); and (2) either annual sales turnover of not more than S$100 million Singapore dollars (SGD), or employment size not exceeding 200 workers [4, 8]. This definition would be comparable to those used in the Asia-Pacific and European countries, where sales turnover and employment size are commonly used to define SMEs. According to the factsheet by the Enterprise Development Centres (EDCs) [8], restaurants in Singapore would be classified as non-manufacturing sectors which include services, construction, agriculture and fishing, and utilities. Following these definitions, the participated restaurants in this study would be classified as SMEs under food and beverage services. B. Definition of Restaurants in Singapore Having defined SMEs in Singapore, this section focuses on defining restaurants in a context of Singapore. Szende et al. [9] provided a board term restaurant as “a food services operation offering customers food and beverages from a menu, usually for consumption on the premises”. Additionally, this study followed the Singapore Department of Statistics’ classifications of restaurants as: (1) restaurants; (2) fast food restaurants; (3) food caterers; and (4) others which include (a) cafes, coffee houses, and snack bars, (b) food courts, coffee shops, and eating houses, (c) pubs (including bars), (d) other restaurants, cafes, and bars, and (e) canteens [10]. C. Significance of Restaurants in Singapore Restaurants constitute almost 36 percent of the food and beverage establishments. In 2011, operating receipts and value added of restaurants amounted to S$2,655 million and S$1,008 million respectively. Restaurants contributed about 38 percent of the total operating receipts and 41 percent of the total value added of the overall food and beverage service industry [10]. As previously indicated, restaurants provide food services to their customers. Thus, they have been a significant component o f S i n g a p o r e’ s g r o w i n g ec o n o my [ 1 1 ]. T h er e ar e approximately 6,500 food establishments and 70,000 corresponding workers in Singapore [10]. Restaurants in Singapore also have cultural impacts on Singapore’s economy. Food is promoted by the Singapore government as one of the eCommerce Internet Commerce EDI Web Commerce Web based advertising Web based distribution Web marketing Customer services CRM SCM Groupware eMail eCollaboration Transaction processing Social media Web 3.0 mCommerce Fig. 2. Definition of eBusiness [1]. reasons for visiting Singapore. A variety of food is presented as an icon of the different ethnic communities which make up Singapore as the multiculturalism nation [12]. D. Definition of eBusiness There are many definitions of eBusiness and one of the first uses was by the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). IBM introduced the term eBusiness when it launched an advertising campaign in 1997 to differentiate its products from other vendors. Prior to this, the term eCommerce was more often used. In this study, eBusiness is defined as any form of commercial transaction involving goods and services which is conducted over a digital medium. Here, eBusiness is taken in the broadest sense of eCommerce. It covers the buying and selling of products and services over the Internet, including those that facilitate online transactions and those enabling the dissemination of information over the Internet. eBusiness encompasses all online interactions that happen between buyers and sellers [3, 13, 14], see Fig. 2. E. eBusiness and Restaurants eBusiness always has a close relationship with restaurants. eBusiness is not a revolution, nor did it suddenly appear. Rather, eBusiness is an evolution of traditional business practices designed to take advantage of the technologies of the Internet age. The first electronic store (eStore) appeared in 1993, where the term eStore represents a set of webpages on the Internet that allows customers to find, evaluate, order, and pay for products [15]. An early example of such eStore was Pizza Hut. Pizza Hut announced its Pizza Net program on August 22, 1994. This was a pilot program that enabled computer users, for the first time, to electronically order pizza from their local Pizza Hut restaurant via the World Wide Web (WWW) [16]. F. eBusiness Readiness Having defined these terms, attention now shifts to the aim of this paper, i.e., assessing the eBusiness readiness of restaurants in Singapore. In this study, eBusiness readiness measures the capability of SMEs’ business environment to seize Internet-based commercial opportunities. Meanwhile, eBusiness may help SMEs in gaining competitive advantages over their rivals, as well as improving the ways in which © 2013 RANGSIT UNIVERSITY RANGSIT JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, VOL. 1, NO. 1, JANUARY-JUNE 2013 SMEs perform their business processes. Unfortunately, it incurs a high level of implementation risk. SMEs need to be able to assess their business whether they are really ready for implementing eBusiness [17-20]. In addition, Huang et al. [18] believed that in the case that SMEs are not ready to implement eBusiness, SMEs would probably like to know where they should improve themselves so that they will be ready for implementing eBusiness in a later stage. 19 TABLE I PROFILES OF RESTAURANTS Type Number Years of of in Food Staff Operation Restaurant A Chinese B Chinese fondue (Steamboat) C Café and bistro (Western Fusion) 5 (Total) 10 4 (Total) 3 months (5 years at the old establishment) Working class, middle income, and family 13 (6 per shift) 9 months (9 years at the old establishment) Working class, middle to upper income, and office workers III. STUDY DESIGN This section addresses the study setting. This study followed a study by Pesonen and Smolander [21] and adopted an observation approach. Three restaurants in Tanjong Pager district, Singapore, were participated for data collection. The author selected the restaurants in the food and beverage services sector to assess their eBusiness readiness. The data collection involved gathering both numeric information as well as text information so that the final findings represent both quantitative and qualitative information. This allowed the author to relate various characteristics in order to explain a phenomenon. Accordingly, the field research allowed the author to gain first-hand knowledge. The aim is to gather information without influencing the environment. The difficulty faced by the author was determining when and what observations to record. Also, an opportunity had to be available and accessible to conduct the observations. In line with the study on eBusiness readiness by Amoroso and Sutton [22], the participants will remain anonymous due to a mutual non-disclosure confidentiality agreement between the author and the restaurants. TABLE II CURRENT DIFFICULTIES THAT RESTAURANTS ARE FACING Restaurant Major Difficulties Owner’s Solutions Closing down the business Profitability, and looking for a job with A high material cost, and more stable income high rental cost B Lack of staff and high rental cost Accepting high prices and paying premium price for staff and rental C High rental cost and staff’s proficient in technology Moving to new premises and improving efficiency of its operational and manpower IV. STUDY RESULTS A. Profiles of Restaurants As indicated, the author will refer the participants only by a code, i.e., Restaurant A, Restaurant B, and Restaurant C. The three restaurants participated in this study are among the most popular ones in the locality or surrounding area of Tanjong Pagar. All of them have been in business for more than five years and have between four and thirteen staffs. The services that these restaurants provide are: (1) cooked to order, (2) hotpot and buffet, and (3) café and bistro. Restaurants A and B have served Chinese cuisines, and Restaurant C has served a Western cuisine. The profiles of all restaurants are simplified and presented in Table I. B. Current Difficulties There are three main difficulties that Restaurant A is currently facing. The first difficulty is the inability to meet the projected profit levels. The second difficulty is the rising cost of ingredients. For example, the food price adjustment is at minimum in order to be competitive. The third difficulty is related to the high cost of rentals. Restaurant A is currently at the end of its lease. The owner of the premises wants to further increase the rent. Market Segments (Groups) Working class, middle income, office workers, young, and family In contrast to Restaurant A, a lack of staff is the major difficulty that Restaurant B is facing. The local regulations in employing non-Singaporean staff are also added to this difficulty. Similar to Restaurant A, high rental cost is another problem at Restaurant B. To cope with these difficulties, Restaurant B is currently accepting high prices and paying premium price for its staff and rental. One of the solutions given is moving to the new premises at the end of each lease term. In line with the two restaurants’ difficulties, Restaurant C is also facing the high rental cost as its top difficulty followed by the staff training in using technology. However, unlike Restaurant B, Restaurant C places its emphasis on operations and manpower to overcome its difficulties. Table II presents an overview of the difficulties. C. Current Business Operations Food, services, quality, and price are the four important management factors that allow Restaurant A to continue serving its customers, as shown in Table III. Restaurant A does © 2013 RANGSIT UNIVERSITY RANGSIT JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, VOL. 1, NO. 1, JANUARY-JUNE 2013 20 Restaurant A TABLE III BUSINESS MANAGEMENT FACTORS Management Factors Food, services, quality, and price B Friendly services, customer satisfaction, and lower profit margin C Friendly and fast services, and comfortable environment and location not have any computerized system or web service. Instead, it is operating manually, and concentrates on providing friendly services and economical food options to its customers. Thus, the maximum number of customers is 50. Restaurant B believes that friendliness and free dishes for the regular customers are the important factors in running its business. Moreover, Restaurant B is happy with a small profit margin and most importantly its customers’ satisfaction. Restaurant B would welcome the Singapore government’s financial support, e.g., subsidization of 50 percent or more for new equipment or appliances purchased. Thus, the weakest management practice at Restaurant B is English communication. Hence, the maximum number of customers at Restaurant B is 70. Similar to the Restaurant B, the Restaurant C also sees friendly and good (fast) services are its strongest management practices; followed by comfortable and well renovated environment. Added to these, the location of the restaurant is also contributed to its management practices. In comparing with the previous premises, the current location of the Restaurant C has more space, facing the main road which is in front of traffic crossing next to the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) station. D. Usage of Computers While computer usage lies at the heart of the EBDF for SMEs (see Fig. 3), there is only one restaurant which has computerized systems to assist the owner and staff in running their business. However, the restaurant which has computerized systems does not have internal information technology (IT) support nor outsource technical support. Two of the restaurants use computers on a daily basis, and have access to the Internet. The primary use of the Internet was for facebook, eMailing, and sourcing information. Two of the restaurants have their own facebook pages. One of the restaurants has planned to have an online ordering and booking systems within a year. The restaurants had indicated that they are considering the adoption of eBusiness in their restaurants within the next two years. E. Experience with eBusiness Common answers given as reasons for not taking up eBusiness were “lack of skills”, “lack of resources”, and “lack of experience people”. Three forces encouraging the adoption of eBusiness were identified. They were “improvement in market opportunity”, “relevance to their businesses”, and Fig. 3. Key elements in the EBDF. Fig. 4. Use of social media activities on Restaurant A. “access to new customers”. When asked about their perception of the impact of the Internet and eBusiness, the participants responded that the Internet and eBusiness had changed and will change the way they conduct business within the next few years. In addition, they expressed the opinions that the Internet will bring positive impact to the business landscape in Singapore. The participants also believed that their use of the Internet and eBusiness, especially social media activities (see Fig. 4), will continue to increase over the next few years. V. STUDY DISCUSSION A. eBusiness Deployment Framework for SMEs Recalling several points made earlier, the EBDF aims to facilitate eBusiness implementation among SMEs through a holistic approach which addressed not only the technological aspects, but also the managerial issues within the specific social and cultural context. While the EBDF specifically developed for Thai SMEs, to enable them to overcome the lack of resources, the EBDF would also enable SMEs in Singapore to distribute the costs of eBusiness by sharing resources. This makes the operating costs lower. It has five major components: (1) application service provider (ASP); (2) professional service provider (PSP); (3) SME enterprise © 2013 RANGSIT UNIVERSITY RANGSIT JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, VOL. 1, NO. 1, JANUARY-JUNE 2013 software; (4) government involvement; and (5) trust facilitation. The complete details of the EBDF was published by the author in the 2006 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Modeling, Control and Automation (CIMCA) [2]. The EBDF was designed by the author and based on specific objectives and strategies. The objectives had been identified through: (1) literature review, to ensure that they were grounded within the theoretical perspective of eBusiness success factors; and (2) interviews, to ensure its relevancy to the context of Thai SMEs. The strategies were formulated to achieve the set of objectives, and in turn, this formulation leaded to the identification of five key elements of the EBDF. They include (1) the employment of ASP and PSP to encourage sharing of resources and cost distribution; (2) the use of SME enterprise software that is an operation centric to support back office integration and utilize cutting edge technologies; (3) pro-active role of government to impose legal framework and regulations, as well as to promote and educate the public on the use of eBusiness; and (4) trust facilitation among all parties. The author also performed statistical analysis to examine the potential acceptance of the framework in 2007 and again in 2013. The statistical result indicated that the EDBF had a potent acceptance among Thai SMEs. It is useful to recall several points made in this paper, in particular the application of the EBDF in an Asian context and eBusiness readiness of SMEs in Singapore. Hence, one of the important issues to be addressed was the need for these restaurants to build integrated business processes within and across organizations. It is essential that each restaurant’s websites should be supported with a mature back office operation and that the eBusiness solutions should be seamlessly integrated. The SME enterprise software was designed to make use of an operation-centric eBusiness system to be provided through an ASP. In this study, the participants have already adopted basic technical infrastructure. The minimum requirements, such as PCs, tablets, electronic funds transfer at point of sale (EFTPOS), and Internet access via broadband, are widespread. As indicated, the participants have their own facebook pages and website advertisement (see Figs. 5 and 6). Although basic technical infrastructure is in place and has been for a while efficient usage of eBusiness is not very widespread nor particularly frequent among the restaurant industry. SMEs’ owners and managers in Singapore need more eBusiness knowledge and skills. Although SMEs report having access to people with eBusiness skills, they report that their o w n limi te d k n o w l ed g e an d s k i lls ar e b a r r ie r s to eBusiness. Better external support and infrastructure are needed. However, all of the SMEs’ owners believe that national infrastructure, technical, financial, and regulatory bodies within Singapore are up to standard. In addition, they can acquire support of eBusiness by local and national governments. 21 Fig. 5. Restaurant C's facebook. Fig. 6. Restaurant B's online advertisement. The participated SMEs are positive about eBusiness. SMEs in Tanjong Pagar strongly viewed eBusiness as an opportunity rather than a threat. Their enthusiasm is neither new nor obviously declining, based on the continued progress in information communication technology (ICT) and eBusiness preparedness over the last few years. The author interprets the results of positive attitudes and basic infrastructure adoption as an indication that the Singaporean SMEs are ready to move forward with eBusiness. The steps that have already been taken are significant, and the author see their progress as a cautious but forward-looking approach to this still new and evolving area. VI. WORK IN PROGRESS The author has been proactively engaged in a number of studies to investigate the applicability of the EBDF among SMEs operating in Thailand and other countries. While this study was targeted at the SMEs’ eBusiness readiness in Tanjong Pagar, Singapore, the author’s primary objective is to understand how the EBDF would fit into the operation of restaurants. This would assist the author in determining what the factors hinder them in implementing eBusiness. An interesting area of future research would be to test the acceptance level of the EBDF in the cultural and economic © 2013 RANGSIT UNIVERSITY 22 RANGSIT JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, VOL. 1, NO. 1, JANUARY-JUNE 2013 settings of Singapore. The detailed findings will be published in future publications. VII. CONCLUSION There are many similarities between SMEs in Thailand and in Singapore. As noted, SMEs because of their size are unlikely to be able to access technical and financial resources in the same way as a larger organization. The role of Singapore government may need to be extended to that of a facilitator, and the eBusiness readiness factors outlined would reinforce this. It appears that SMEs under a restaurant sector in Singapore are already aware of the potential benefits of adopting eBusiness. The result of this study also indicated that a high level of eBusiness readiness is not exclusively a Western attribute, and Asian countries such as Singapore also have a high level. In refining the EBDF, the starting point is to examine Asian countries that have a high level of eBusiness readiness for essential characteristics and any lessons that can be learned from their experience. SMEs in Singapore provide such an opportunity. [16] R. G. Fuisz and J. M. Fuisz, “Method and apparatus for permitting stagedoor access to on-line vendor information,” US Patent 8255279 B2, May 2011. [17] Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, The Wisdom Exchange E-Business Readiness Assessment. Toronto: Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2001. [18] J. H. Huang, W. W. Huang, C. J. Zhao, and H. Huang, “An e-readiness assesment framework and two field studies,” Communications of the Association for Information Systems, vol. 14, no. 1, 2004. [19] D. Jutla, P. Bodorik, and J. Dhaliwal, “Supporting the e-business readiness of small and medium-sized enterprises: Approaches and metrics,” Internet Research, vol. 12, no. 2, 2002, pp. 139–164. [20] J. Oliver and P. Damaskopoulos, “SME eBusiness readiness in five eastern european countries: Results of a survey,” in Proceedings of the 15th Bled Electronic Commerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia, 2002. [21] T. Pesonen and K. Smolander, “Observations on e-business implementation capabilities in heterogeneous business networks,” in Proceedings of the 11th IFIP Conference on e-Business, e-Service, and e-Society, pp. 212–226, Kaunas, Lithuania, October 2011. [22] D. Amoroso and H. Sutton, “Identifying e-business readiness factors contributing to IT distribution channel reseller success: A case analysis of two organizations,” in Proceedings of the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, vol. 8, Washington, DC, 2002. REFERENCES [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] S. Jantavongso and R. K.-Y. Li, “A new age e-business model for SME,” in Proceedings of the 9th Australian World Wide Web Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 2003. L. F. Sugianto and S. Jantavongso, “eBusiness adoption studies focusing on Thai SMEs,” in Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Modelling, Control and Automation, Washington, DC, 2006. K. Blashki and S. Jantavongso, “E-business in SMEs of Thailand: A descriptive survey,” in Proceedings of the International Conference Information Resources Management, pp. 448–452, Washington, DC, 2006. Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore, “Taxation of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Singapore,” 2007. Available: www.itdweb.org/smeconference/documents/singapore_paper.pdf Wikimedia Commons, “Tanjong Pagar,” 2013. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tanjong_Pagar_Group_Repre sentation_Constituency_locator_map.png T. E. Ser, B. S. A. Yeoh, and J. Wang, Tourism Management and Policy: Perspectives from Singapore. New York: World Scientific, 2001. M. Grillet, “Internationalization towards China after its accession to the WTO. Are there opportunities for European SMEs?,” Master thesis, Department of Oriental and Slavic Studies, Catholic University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2003. Enterprise Development Centres, “Factsheet on New SME Definition,” Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore, 2011. P. Szende, J. K. Pang, and H. Yu, “Experience design in the 13th century: The case of restaurants in Hangzhou,” Journal of China Tourism Research, vol. 9, no. 1, Febuary 2013, pp. 115–132. Department of Statistics, “Economic Surveys Series 2011 – Food & Beverage Services,” Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore, 2012. SPRING Singapore, “Singapore Food Manufacturing Industry Directory,” Singapore, 2010. B. H. Chua, Life is not Complete without Shopping: Consumption Culture in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2005. E. Turban, D. Leidner, E. McLean, and J. Wetherbe, Information Technology for Management: Transforming Organizations in the Digital Economy. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2006. D. T. Cadden and S. L. Lueder, Small Business Management in the 21st Century. New York: Flat World Knowledge, 2012. G. Philipson, Australian eBusiness Guide. North Ryde, Australia: CCH Australia Limited, 2001. © 2013 RANGSIT UNIVERSITY