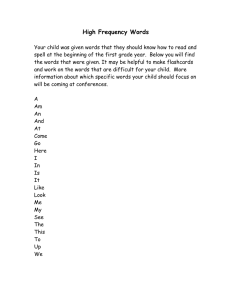

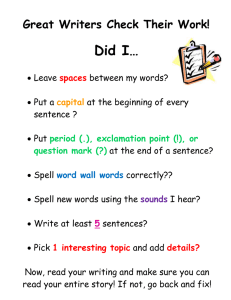

When I first read Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, I was a student struggling to make sense of it. Now as I read it on the 70th anniversary of its posthumous publication, I am a teacher struggling to make sense of it. In my job, I teach adults who speak English – or at least have a good grasp of it as a spoken language – how to read and write. And not how to read and write ‘professionally’, but rather how to connect sounds to shapes on a page and vice versa, how to spell the language’s most common words, and how to write a complete sentence. There is a member of my class who, although he can say and use the words we study, and has a good grasp of consonants, will not include vowels when he spells. I will ask him to spell the word ‘went’, for example, and he will spell out ‘wnt’. If I correct him once, this currently makes no difference – the next time, he will spell without vowels just the same. As you may imagine, I can find this very frustrating. Wittgenstein writes of a similar case in one of the central sections of the Investigations. He describes teaching a pupil the series 0, n, 2n, 3n, etc, where n = 2. Only, when the pupil gets to 1000, he writes 1000, 1004, 1008, 1012: We say to him: ‘Look what you’re doing!’ – He doesn’t understand. We say: ‘You should have added two: look how you began the series!’ – He answers: ‘Yes, isn’t it right? I thought that was how I had to do it.’ – from §185 of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations (4th ed, 2009) Wittgenstein then compares this to a case of someone who does not react naturally to a gesture of pointing: someone who looks in the direction from fingertip to wrist instead of following the line beyond the fingertip. We might also think of a cat, staring blankly at a pointing finger. He goes on to suggest that the rules we take for granted as governing all manner of human activity, from mathematics to the grammar of propositions, cannot be explicated by the Platonic tradition of reference to ineffable objects, nor by a subjective ‘interpretation’ at the moment of each instantiation of the rule. Rather, they in a sense rely on shared agreement in natural inclination, or in common practices. Our understandings are just what we do. They are our form of life. (This is, it strikes me, a very teacherly attitude. Every teacher knows that it is no use just having a learner say they understand: we have to watch them do it.)