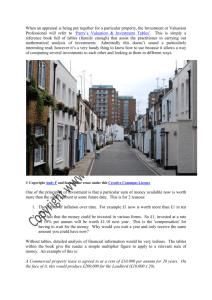

Peter Wyatt - Property Valuation (2013, Wiley-Blackwell) - libgen.li

advertisement