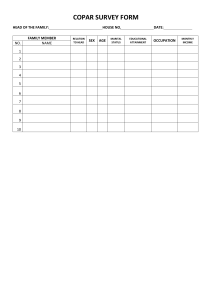

Gender, Social Change, and Educational Attainment Author(s): Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn Source: Economic Development and Cultural Change , Vol. 51, No. 1 (October 2002), pp. 109134 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/345517 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic Development and Cultural Change This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Gender, Social Change, and Educational Attainment* Ann M. Beutel University of Oklahoma William G. Axinn University of Michigan Sociological research has focused much attention on processes of educational attainment. In part, this is because of direct benefits thought to result from education and, in part, because educational attainment is considered a key step in other processes of attainment, such as occupational attainment.1 Because education gives individuals opportunities to achieve status mobility, the links between ascribed dimensions of status, such as gender, race, and education, have always drawn sociologists’ attention. The spread of mass education constitutes a fundamental social transformation and a watershed in attainment processes because it opens up previously unavailable status mobility routes. Rarely, however, do we have an opportunity to examine directly the relationship between ascribed dimensions of status and educational attainment during the very beginning of the spread of mass education. In this article, we use a unique set of measures from a setting in the midst of the spread of education to examine both the impact of gender on processes of educational attainment and the ways in which community-level social change attenuates the impact of gender on education. This article tests several key hypotheses regarding this fundamental social transformation. First, we investigate hypotheses regarding the impact of gender on educational attainment during the spread of mass education. Although a large body of previous research documents important gender differences in educational attainment from settings in which education is already widespread, little is known about the connections between gender and specific dimensions of the educational attainment process, such as enrollment and drop-out rates, at the onset of universal education. Second, we test hypotheses regarding the impact of social changes at the community (i.e., local) level on individual educational attainment. These hypotheses predict that macro-level changes in educational, employment, and consumption opportunities will increase school attendance. 䉷 2002 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0013-0079/2003/5101-0005$10.00 This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 110 Economic Development and Cultural Change Third, we test key hypotheses regarding the impact of local-level social change on the individual-level relationship between gender and educational attainment. Our framework for studying this overall social transformation uses the social organization of the family as the key intervening link between macro-level social change and the impact of gender on educational attainment. The setting on which we focus is the multiethnic, rural population of south-central Nepal. Rural Nepal provides an ideal setting for our study because secular education was entirely unavailable prior to the early 1950s but has become universal within the lifetimes of current residents. Simultaneously, the proliferation of education has been accompanied by dramatic social changes in the availability of wage labor employment, the spread of markets, and the distribution of transportation infrastructure. Historically, status attainment in this setting was in large part determined by caste and gender, whereas now these social changes have drastically transformed attainment processes. With detailed community-level measures of social change and equally detailed individual-level life histories of educational experience, we can now thoroughly examine the relationships among gender, social change, and educational attainment. I. Theoretical Framework A. Gender and Educational Attainment A considerable amount of previous research documents important differences in educational attainment between men and women. For example, research conducted in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s showed that women tended to achieve lower levels of both educational attainment and intergenerational occupational mobility than men.2 Furthermore, this body of research found parental characteristics to be important determinants of educational attainment for both men and women but that boys perceived higher parental encouragement for education than girls.3 In addition, those studies of attainment processes that included factors particularly relevant to women’s adult family roles, such as dating frequency, age at first marriage, and age at first birth, found significant effects on educational outcomes for females but not for males.4 This evidence suggests that gender differences in educational attainment may arise because of gender differentiation in adult roles and the emphasis on family-related roles for women.5 In combination with actual or perceived role conflict between the pursuit of the family role and the pursuit of education and career roles, the emphasis on family roles for women may lead them to abandon schooling or their parents to discourage them from educational pursuits.6 Research from agricultural societies has also shown the important effects of gender on educational participation and attainment, with girls much less likely to be enrolled in school at any point in time and achieving lower levels of educational attainment than boys.7 Consistent with the findings of status attainment research in the United States, this suggests that gender role differentiation has important effects on girls’ education. In agrarian societies This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 111 where female roles are defined largely in terms of home and family, parents are likely to have significant incentives to keep their daughters at home and out of school.8 Rural Nepal is certainly such a society, and the need for girls’ labor on the farm and in the household has been cited as a major reason for not sending girls to school or for sending girls to school for relatively short periods of time regardless of the level of household wealth.9 Thus, even though parents may desire some amount of schooling for daughters as a means of enhancing their marriage prospects, perceived conflict between women’s roles in the family and their educational and work roles motivates parents to discontinue their daughters’ schooling at a significantly earlier stage than is true for their sons.10 Empirically, therefore, we expect parents to be less likely to enroll daughters in school than sons and more likely to take their already enrolled daughters out of school than sons. In settings such as rural Nepal, the consequences of perceived genderspecific role conflict between family roles and work roles can be exacerbated by gender differences in marriage patterns and parental dependence on children for old-age security. In the South Asian region, most parents depend on income provisions from their children for financial support in old age.11 Furthermore, in North India and Nepal, daughters generally leave their parents’ household at marriage to reside with their parents-in-law.12 As a result, parents are much more inclined to invest in their sons’ human capital than in their daughters’ human capital, as investments in daughters are generally believed to benefit in-laws, not natal families. Moreover, although wage labor opportunities have been spreading steadily through South Asia, males are much more likely to take wage labor jobs than females, and many believe these money earning opportunities are relatively unavailable to women.13 This further reduces parental motivation to educate daughters. Overall, therefore, these setting-specific characteristics of rural Nepal reinforce our predicted gender difference effects on educational enrollment and attainment so that we expect gender differences to be particularly great in our study. B. Social Change and Educational Attainment Several dimensions of social change are likely to have an impact on educational attainment. First, the proliferation of schools is itself likely to promote enrollment and attainment. As schools become increasingly available, the costs of sending children to school will decline, and parents will find it easier to enroll their children. Likewise, the longer schools remain nearby, the more common school attendance is likely to become. Second, the spread of wage labor employment opportunities is also likely to stimulate greater educational attainment. School enrollment allows individuals to invest in their human capital in order to increase their chances of obtaining a wage labor job and mobility among jobs.14 This is particularly likely to be true in South Asia because the British system of formal education, adopted throughout much of the region, was based on principles of certifying This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 112 Economic Development and Cultural Change individuals for specific jobs, especially governmental jobs. As a result, as wage labor employment opportunities proliferate, motivation to enroll in school is expected to increase as a means of securing those jobs. Likewise, we expect motivation to educate children to increase with longer exposure to wage labor jobs nearby. Third, the spread of markets is likely to increase school enrollment and educational attainment. Here, the mechanisms are indirect. As markets spread throughout rural Nepal, goods and services become more widely available, but only to those who have the money to purchase those goods and services. Thus, the spread of markets is expected to increase the demand for money, which will encourage individuals to pursue wage labor jobs and higher wages among those jobs, and the desire to obtain higher paying jobs is expected to motivate educational attainment.15 Because these mechanisms are indirect, lags may occur before the spread of markets stimulates greater educational attainment. Nevertheless, the longer markets are present nearby, the greater are the chances that parents will send their children to school and keep them there. Fourth, the spread of improved transportation infrastructure is also likely to increase educational attainment. This is because improved transportation infrastructure facilitates access to schools, wage labor employment opportunities, and markets. By increasing access to these other social institutions, each of which is expected to motivate educational attainment by itself, improved transportation infrastructure is also likely to increase school enrollments. The social changes in the availability of schools, wage labor jobs, markets, and transportation are all likely to increase the chances that parents will enroll and keep their children in school. However, in order to understand the impact of these same social changes on gender differences in the likelihood that parents send their children to and keep them in school, we must first consider the impact of these same social changes on the social organization of family life. This is because we believe the social organization of family roles is a fundamental determinant of gender differences in educational attainment. C. Social Change, the Social Organization of Families, and Gender Difference in Education We use the family mode of social organization framework to consider the impact of social change on the social organization of families. Our choice of this framework is rooted in the premise that improved transportation and communication, monetization of the economy, and population growth increase the division of labor in society. Emile Durkheim argued that these factors increase the numbers of people who interact with one another, or the “moral density” of society.16 He mentioned three specific mechanisms that predicate the division of labor: population concentration, the formation and development of cities, and improved communication and transportation.17 This framework recognizes that changes in transportation, communication, and monetization can reorganize not only production but a wide variety of other social activities as well, which has a great impact upon the social organization of families. This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 113 The family mode of social organization framework considers a wide array of social changes and their potential influence on individuals in families.18 The framework builds on previous research that focused exclusively on the family mode of production and extends to family modes of social organization across a variety of domains: consumption, residence, recreation, protection, socialization, procreation, and production.19 Historically, most of these activities of daily living were organized within the family.20 Yet, as social changes created new nonfamily institutions to organize these activities, they increasingly took place outside the family. No society is expected to be completely organized inside or outside of families, but the nonfamily and family modes of social organization are two ideal types that aid our understanding of social change and the family. Social changes, such as the spread of nonfamily schools, nonfamily employment opportunities, nonfamily consumption opportunities (markets), and nonfamily transportation, alter the organization of social life so more of social life takes place outside the family. As activities of daily living increasingly take place outside the home and away from the family, the structure of social interactions changes and alters social relationships with both family members and others outside the family. This reorganization of family life is the key link between macro-level social changes and micro-level changes in adult roles and perceived role conflict between family roles and nonfamily roles. As nonfamily social institutions spread and more of social life takes place outside the family, family-related adult roles are likely to become a less significant feature of adult roles. With regard to educational attainment, the consequence is quite likely reduced gender differences in school enrollment. Again, time lags are likely to be a key feature of this impact of new nonfamily institutions on gender differences in education, but the longer these new nonfamily institutions are part of daily life, the smaller the gender differences we expect to find in the propensity of parents to send their sons and daughters to school and keep them there. In a highly gender-stratified setting such as rural Nepal, the impact of new nonfamily institutions may not be sufficient to eliminate gender differences in enrollment and attainment, but they are likely to significantly reduce them. Thus, in this setting, as education begins to spread, we expect sons to be more likely to attend and to stay in school than daughters. The social changes in the spread of wage labor employment, markets, and transportation that accompany the spread of schools will themselves increase enrollment. However, the spread of these same nonfamily institutions is likely to produce a fundamental change in the organization of daily social life that reduces the conflict between adult family roles and adult work roles. As a result, these same social changes are eventually likely to reduce gender differences in educational attainment. Thus, in this setting, the spread of new nonfamily social institutions may be the key to the success of mass education in providing a new route to status attainment that is independent of key ascribed statuses, such as gender. This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 114 Economic Development and Cultural Change II. The Study A. Setting The setting for our study is Western Chitwan Valley in south-central Nepal. Nepal is an ethnically diverse country of approximately 22 million people and is located in the central Himalayas. The country spans approximately 500 miles in length and only about 60 miles north to south. Chitwan is 100 miles southwest of the capital city, Kathmandu. The population of Chitwan in 1996 (the year of our data collection) was approximately 414,261. Until the 1950s, Western Chitwan Valley was covered with virgin forests and infested with malaria-carrying mosquitoes. In the mid-1950s, the Nepalese government (with assistance from the United States) began a program to clear much of the forests, eradicate malaria, and distribute land to settlers from the higher Himalayas, who were attracted to the area because of the rich soil and flat terrain of the valley. Individuals from a variety of religious and ethnic groups, which differ widely on a range of attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, came to inhabit the region. High-caste Hindus form the largest religious-ethnic group in the valley, but large numbers of low-caste Hindus, Newar, Tibetoburmese, and indigenous ethnic groups reside there as well. Chitwan was relatively isolated from the rest of the country until the late 1970s when major roads were built, linking the largest town of Narayanghat to the eastern, northern, and western portions of the country. As a result of the new roadways, Narayanghat became a transportation hub within the country, and a variety of government offices, businesses, and employment opportunities developed in Narayanghat and spread from Narayanghat throughout Western Chitwan Valley. Thus, over the course of approximately 40 years, the valley changed greatly from being relatively isolated to being the location of a vast array of nonfamily institutions. As a result, the social organization of daily life in Chitwan has shifted from virtually all social activities being organized within families to many social activities becoming organized outside of the family. The focus of our investigation here is the spread of mass education. Formal education was virtually nonexistent in Nepal until the 1950s when the British system of formal schooling was introduced.21 That system was based on the principles that all children, regardless of social background, ethnicity, or gender, have a right to an education and that the national government should ensure equal access to education.22 Despite this, large numbers of Nepalese children do not attend school. In 1990, the combined primary and secondary gross enrollment ratio in Nepal (number in school/number in school eligible age group) was 39 for females and 80 for males.23 This contrasts with a combined primary and secondary gross enrollment ratio in the United States of 99 for females and 99 for males.24 Data on school enrollment for the Chitwan district only are unavailable. However, the higher adult literacy rate in Chitwan (49.46%) as compared with that of the entire country (36.75%) suggests that residents of Chitwan have had comparatively high educational opportunities.25 The data we analyze here demonstrate a dramatic increase This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 115 Fig. 1.—Number of schools and students over time over time in enrollment in school (described below). This increase was so dramatic, in fact, that, by 1996, 100% of the children ages 5 and 6 in our study area had been to school at least for one day. The spread of formal education in Western Chitwan paralleled the spread of education throughout the rest of Nepal. The first school was established in 1954, and both the number of schools and the number of students enrolled in schools increased dramatically in the decades that followed. Through a combination of archival, ethnographic, and survey methods, we gathered a detailed set of histories for all the schools that had ever existed in the study area between 1946 and 1995.26 Figure 1 displays data from those histories, documenting the growth of both the number of schools and the number of students enrolled in those schools between 1955 and 1995. Clearly, the spread of education in the area has been dramatic, reaching a total of 123 schools and 43,785 enrolled students by 1995. Gender differences in education have been equally dramatic in this setting. In Nepal in general, girls are much more likely than boys to not be enrolled in school: of the children not enrolled in schools, approximately twothirds are girls. Girls are also more likely to repeat grades and drop out of school.27 Girls’ participation in schooling has lagged behind boys’ despite a variety of government programs intended to promote their involvement in education.28 In Chitwan, however, the gender gap in schooling has narrowed much more quickly than in most other regions in Nepal. As figure 2 shows, only 6.7% of Chitwan students in 1954 were girls, but by 1995, 47.4% of students were girls. Our interviews with parents in Chitwan also indicate that, This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 116 Economic Development and Cultural Change Fig. 2.—Percentage of total students who are female over time by 1996, parents placed a high value on educating both their sons and their daughters. In response to survey questions (described below), 93% of respondents rated attending college as very important for their sons and 89% rated attending college as very important for their daughters. In addition, there is relatively little variation in the importance placed on college education for daughters by gender of the parent: in the survey, 93% of male respondents and 84% of female respondents rated sending their daughters to college as very important. One of the key features that makes Chitwan different from other parts of rural Nepal has been the tremendous proliferation of nonfamily organizations and services throughout the area. In addition to collecting histories of schools, we used neighborhood history calendars to collect histories of exposure to new nonfamily organizations and services for a sample of 171 neighborhoods in Western Chitwan Valley.29 These histories allow us to calculate the number of minutes from each neighborhood to the nearest school, employer, market, or transportation service, independently for each calendar year, as the spread of these services brings them much closer to each neighborhood. Figure 3, which displays changes over time in the mean minutes by foot to the nearest school, employment, market, and transportation service, illustrates how dramatic changes in nonfamily organizations and services in western Chitwan have been. Although the distance from the average neighborhood in western Chitwan to the nearest nonfamily service was well over an hour in the 1950s, by the 1990s the average neighborhood in western Chitwan had several different nonfamily services and organizations within a This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 117 Fig. 3.—Mean minutes by foot to nearest nonfamily service or organization over time. 20-minute walk. The dramatic change in the proliferation of nonfamily services and organizations (described in fig. 3) happened over the same span of years as the dramatic rise in the proportion of students who were female (described in fig. 2). In what follows, we use detailed survey data on individual children’s schooling experiences to examine the extent to which these two changes are linked. B. Survey Data Our statistical analyses of the impact of gender and social change on educational attainment use data from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS). The CVFS collected data from neighborhoods, households, and individuals. Neighborhoods served as the primary sampling unit and were defined as clusters of 5 to 15 households. In these small neighborhood clusters, residents interact with one another on a daily basis. Neighborhoods were selected through an equal probability, systematic sample of all neighborhood clusters in Western Chitwan Valley, with the resultant sample consisting of 171 neighborhoods. Within each neighborhood, every individual between the ages of 15 and 59 was interviewed in 1996. Nonresident spouses of residents also were interviewed to provide comprehensive data from both husbands and wives. Using life history calendars, detailed measures of life events, such as marriage, migration, schooling, and childbearing, were collected.30 For each respondent, these life history calendars also were used to collect a complete history of the respondent’s children’s schooling experiences. The survey in- This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 118 Economic Development and Cultural Change terviews enjoyed a very high response rate of 97%, yielding life history measures from 5,272 individuals. C. Measures Education. Our statistical analyses of the impact of gender and social change on educational attainment focus on two key dimensions of the educational attainment process: children’s entry into school and children’s dropping out of school. To simplify the analyses and to insure comparable measurement is available for all those included in the study, we focus on the schooling experiences of firstborn children. The measures of these children’s schooling experiences come from interviews with their mothers. The sample of mothers we include in our analysis are those women who were between the ages of 25 and 54 at the time of the interview and had at least one child (N p 1,159). In the analysis of school entrance, the dependent variable measures whether a woman’s firstborn child entered school between the ages of 3 and 12. This variable is operationalized as the hazard of entering school, or the probability of entering school in any year given the child has not already entered school. In the analysis of school exit, which was limited to those firstborn children who did enter school between ages 3 and 12, the dependent variable measures whether they ever exited school by age 15. This variable also is operationalized as a hazard rate—here, the hazard of first exit from schooling. We choose age 15 as the upper limit because it is unlikely that children would have left school because of graduation by that age. Gender and social change. Two key independent variables are child’s gender and social change. We measure gender of the child with a dichotomous variable, coded 1 if the child is male and 0 if the child is female. As discussed above, the dimensions of social change on which we focus are the proliferation of nonfamily schools, nonfamily wage labor employment opportunities, nonfamily markets, and nonfamily transportation services. We used neighborhood history calendar measures to operationalize our measurement of the spread of these nonfamily organizations and services.31 These calendars measured the number of minutes’ walk from the neighborhood to the nearest school, employment opportunity, market, or transportation service. Schools were defined as the nearest location (but not necessarily a physical building) of nonfamily instruction aimed at children and youth. Employment opportunities referred to the nearest employer who employs 10 or more individuals for pay. Markets were defined as the nearest location of two or more shops where goods and services are sold for money. Transportation services referred to the nearest location where a resident could board a public motorized vehicle and ride for a fee. The measures of these distances employed no boundaries, so all distances were possible. Our aim in the present analyses is to assess the impact of nearby nonfamily organizations and services, so we focus on nonfamily organizations and services within 10 minutes’ walk of the neighborhood.32 Because our aim is also to assess the impact of length of exposure to these This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 119 nonfamily organizations and services, we constructed variables that measured the number of years that schools, employment opportunities, markets, or transportation services were within a 10-minute walk of the neighborhood. To test our hypotheses regarding the impact of social change on the relationship between gender and educational attainment, we include an interaction term for the number of years of each nonfamily service or organization (schools, employment opportunities, markets, transportation services) and gender of the child. These variables, discussed in greater detail below, allow us to examine whether gender differences in educational attainment diminish with increased exposure to nonfamily services and organizations. Controls. A good deal of previous research demonstrates that parental social background, particularly education, influences children’s educational and occupational attainment.33 Parental aspirations for children and self-aspirations both play key roles in transmitting the effects of parental education on their children’s educational attainment.34 In fact, these intergenerational effects on children’s schooling may be particularly strong at the beginning of the spread of mass education. This is because in settings where schooling is inaccessible for the majority of individuals, intergenerational mobility is constrained and individual attainment depends more on family background.35 Parental schooling experiences also may have an important impact on the gender gap in educational attainment. Research has shown that parents’ education has an important effect on daughter’s schooling.36 This is in part because parents who have been formally educated are more likely to place a high value on education for daughters as well as sons than are parents who have not been formally educated.37 To control for these important intergenerational effects, our multivariate models include measures of mother’s father’s education and mother’s education. Mother’s father’s education is measured as a dichotomous variable, coded 1 if the mother’s father had any formal schooling. Mother’s education is measured as the number of years of schooling she received up to 1 year before the analysis interval begins—that is, until her firstborn was 2 years of age in the school entrance analysis and until 1 year before her firstborn went to school in the school exit analysis.38 Ethnicity may influence educational attainment because religious or ethnic groups often differ in the value they place on education. For example, in the United States, research has found Jewish identity to have a much larger effect (via parental aspirations and self-aspirations) than other religious identities on educational attainment.39 Similarly, research in Nepal has shown that children who are high-caste Hindu or Newar—religious-ethnic groups that place a high value on education in this setting—are more likely than others to be enrolled in school and to attain high levels of educational attainment.40 Therefore, our multivariate models also include controls for mother’s religious-ethnic identity: high-caste Hindu, low-caste Hindu, Hill Tibetoburmese, Newar, or Terai Tibetoburmese. High-caste Hindu serves as the reference group in the analysis. Historically, members of that group have had the greatest This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 120 Economic Development and Cultural Change access to educational and other opportunities and, as a result, have been the most highly educated. Identity in each of the other groups is coded as a dichotomy. Newars, who practice a mixture of Hinduism and Buddhism, are another group who have enjoyed both access to and participation in formal schooling. The Hill Tibetoburmese, who mainly follow the principles of Buddhism, have not been characterized by the same high level of devotion to education as the high-caste Hindus or the Newars. In contrast with these groups, low-caste Hindus have had many fewer educational opportunities. Finally, the Terai Tibetoburmese, a group indigenous to the region, has had much less access to educational and other opportunities than have other groups. Because a key aim is to assess the impact of social change at the community level on educational attainment at the individual level, we also control for the migration experiences of the mothers. These migration experiences take individuals outside of the communities we have measured, possibly exposing them to a different set of community characteristics. We include two controls for migration. The first is a non–time varying measure of any migration experience (i.e., any residence outside the neighborhood) between the time of the mother’s birth until 1 year before the analysis interval began—that is, until her firstborn was 2 years of age in the entrance analysis and 1 year before her firstborn entered school in the exit analysis. The second is a timevarying measure of whether the respondent is outside the neighborhood during the analysis interval—starting when her firstborn was 3 years of age in the entrance analysis and the year her firstborn started school in the exit analysis.41 Finally, our multivariate models control for the mother’s birth cohort using three dummy variables: 1962–71 (ages 25–34 at the time of the survey), 1952–61 (ages 35–44 at the time of the survey), and 1942–51 (ages 45–54 at the time of the survey). Each respondent is coded 1 on one of these variables and 0 on the two other variables. The youngest birth cohort serves as the reference group in the analysis. These controls help to insure that differences across birth cohorts are not responsible for the pattern of relationships we observe among our other measures. Descriptive statistics for the measures of social change, gender, and nontime varying controls are shown in table 1. Table 1 does not describe the measures of the hazard of entrance into school, exit out of school, or timevarying covariates because the values of these variables change by year in our dynamic person-year analysis (described below). D. Analysis Strategy We use event history methods to model each mother’s firstborn child’s risk of entering or exiting school. Because the life history calendars collected measures precise to the year, we treat person-years as the unit of exposure to risk and estimate our models using discrete-time methods. Thus, person-years of exposure to the risk of entering or exiting school is the unit of analysis. As noted earlier, firstborns between 3 and 12 years of age are at risk of school entrance, and firstborns who have entered school and are between the ages This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 121 TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics for Measures Used in Analyses Mean Gender of child (1 p male) Number of years service or organization within a 10-minute walk until child age 2: School Employment opportunities Market Transportation Maternal characteristics: Mother’s father has any schooling Mother’s years of education Mother ever move (until child age 2) Mother’s religious-ethnicity: High-caste Hindu Low-caste Hindu Hill Tibetoburmese Newar Terai Tibetoburmese Mother’s birth cohort: Born in 1962–71 Born in 1952–61 Born in 1942–51 Standard Deviation Minimum Maximum .49 .50 11.79 4.52 8.19 6.41 11.16 9.40 10.35 9.56 0 0 0 0 42 43 43 40 .22 2.24 .41 4.08 0 21 .99 .11 .48 .11 .18 .07 .17 .43 .35 .22 of 3 and 15 are at risk of school exit. We estimate the models using logistic regression, which can be represented by the equation: ln ( ) p p a ⫹ S (Bk)(Xk) , 1⫺p where p is the yearly probability of entering or exiting school, p/1⫺ p is the odds of school entrance or exit occurring, a is a constant term, Bk represents the effects parameters of the explanatory variables, and Xk represents the explanatory variables in the model. Using person-years of exposure to risk as the unit of analysis increases the sample size, but this procedure does not deflate standard errors and provides appropriate tests of statistical significance.42 We transform the logistic coefficients by exponentiating them, so that the coefficients we show in the tables are multiplicative effects on the odds of entering or exiting school in any one year. A coefficient of 1.00 indicates no effect on the odds, a coefficient greater than 1.00 indicates a positive effect on the odds, and a coefficient less than 1.00 indicates a negative effect on the odds. Because the odds of entering or exiting school in any given year are quite low, these odds are quite similar to rates. Therefore, we will some- This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 122 Economic Development and Cultural Change times describe the coefficients we present as effects on the rates of entering or exiting school. III. Results A. School Entrance Table 2 presents the results of our analyses of the effects of gender and locallevel social change on school entrance. For each neighborhood service or organization, there are two columns of results. The first column shows the results for a model without any interaction terms, and the second column shows the results for a model that includes an interaction term for the nonfamily service or organization and gender of the child. Looking first at the results for models without interaction effects, we see that gender has large effects on school entrance that are of a similar magnitude across models, indicating that boys enter school at higher rates than girls. For example, in the first model of school presented in table 2, we see that boys enter school at rates 51% higher annually than girls. Thus, our hypothesis regarding the effect of gender on educational attainment is supported. We also find support for our hypothesis regarding the effect of locallevel social change on educational attainment. All of the nonfamily service and organization variables have significant effects on rates of entering school. Each year that a school has been within a 10-minute walk of the neighborhood increases the annual rate of school entrance by 1%, although the effect of school is only marginally significant at the .10 level; each year that an employment opportunity has been within a 10-minute walk increases the annual rate of school entrance by 2%; each year that a market has been within a 10minute walk increases the annual rate of school entrance by 3%; and each year that transportation service has been within a 10-minute walk increases the annual rate of school entrance by 3%. The rate of sending a child to school, then, is much higher in neighborhoods where nonfamily services and organizations have been nearby for a long period of time than in neighborhoods where nonfamily services and organizations have been nearby for a short period of time. For example, the difference between living in a neighborhood that has had a market within a 10-minute walk for 25 years and living in a neighborhood that has had a market within a 10-minute walk for 5 years results in an 81% increase in the annual rate of entering school (1.03 20 p 1.81). Thus, the proliferation of nonfamily institutions, as measured by number of years that nonfamily services and organizations have been within a 10minute walk of the neighborhood, increases the likelihood that parents will send their (firstborn) child to school.43 The effects of social background, as measured by maternal characteristics, are similar across the first set of models. Consistent with prior evidence on educational attainment, both of the measures of education are significant, indicating that (firstborn) children whose maternal grandfather and mother have been formally educated are more likely to enter school. Across the first set of models, the fixed measure of mother’s migration has no effect while This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 123 Fig. 4.—Predicted equations for rates of school entrance for boys and girls by presence of markets. the time-varying measure of migration has a statistically significant effect on the rate of school entrance. Turning to ethnicity, we see that, relative to highcaste Hindus, children of Newar women have higher rates of school entrance and children of low-caste Hindus, Hill Tibetoburmese, and Terai Tibetoburmese women have lower rates of school entrance. These findings support the idea suggested earlier that historical religious-ethnic group differences in the value placed on education and access to education and other opportunities influences the likelihood of sending children to school. Finally, mother’s birth cohort is also significant. The earlier a mother’s birth cohort, the less likely it is that her firstborn child enters school. In the second set of models, we add an interaction term for the nonfamily service or organization and gender of the child. As noted earlier, the interaction term is used to test our hypothesis that, as new nonfamily services and organizations spread, the influence of gender on educational attainment will be reduced. In fact, this is what we find. In each of the models, the interaction term has a statistically significant effect, although it is only marginal (P ! .10) in the model of employment opportunity. These coefficients, which all have values less than 1.00, indicate that the longer a nonfamily service or organization has been nearby, the higher the rate of school entrance will be for girls. We illustrate the relationship between gender and local-level social change in figure 4. As an example, we plot the predicted equations by gender of the child when a market has been within a 10-minute walk of the neighborhood for 1 year, 5 years, 15 years, and 25 years for a child who was 5 years of age at school entrance and whose mother had the following characteristics: her father had been formally educated, she had received 3 years This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Discrete-Time Hazards Estimates of the Effects of Gender, Nonfamily Services and Organizations, and Maternal Characteristics on School Entrances School (1) 124 This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms TABLE 2 Gender of child (1 p male) Community characteristics: No. of years service or organization within a 10-minute walk No. of years service or organization within a 10-minute walk # gender of child Maternal characteristics: Mother’s father’s education Mother’s education Mother’s migration (fixed) Mother’s migration (time-varying) Employment (2) (1) (2) Market (1) Transportation (2) (1) (2) 1.51*** (4.65) 2.01*** (5.41) 1.51*** (4.63) 1.60*** (4.78) 1.51*** (4.60) 1.78*** (5.10) 1.50*** (4.55) 1.79*** (5.47) 1.01⫹ (1.53) 1.02*** (3.16) 1.02*** (3.22) 1.03*** (3.32) 1.03*** (5.71) 1.04*** (5.82) 1.03*** (4.84) 1.04*** (5.65) .99⫹ (⫺1.40) .98** (⫺3.05) 1.54*** (3.72) 1.13*** (8.28) .73 (⫺.80) .77** (⫺2.63) 1.55*** (3.75) 1.13*** (8.30) .74 (⫺.75) .77** (⫺2.67) 1.51*** (3.53) 1.12*** (8.05) .73 (⫺.82) .74** (⫺3.06) 1.50*** (3.46) 1.12*** (7.88) .74 (⫺.76) .74** (⫺3.05) .98** (⫺2.39) 1.51*** (3.52) 1.11*** (7.04) .69 (⫺.96) .72*** (⫺3.28) 1.50*** (3.45) 1.11*** (6.89) .70 (⫺.90) .72*** (⫺3.29) .97** (⫺3.04) 1.45*** (3.19) 1.12*** (7.79) .70 (⫺.89) .74*** (⫺3.11) 1.44** (3.10) 1.12*** (7.76) .73 (⫺.79) .73*** (⫺3.16) Mother’s religious-ethnicity (reference p high-caste Hindu): Low-caste Hindu Newar Terai Tibetoburmese Mother’s birth cohort (reference p 1962–71): Born in 1952–61 Born in 1942–51 125 This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Hill Tibetoburmese x2 Degrees of freedom Person-years (N) .53*** (⫺4.32) .79* (⫺1.91) 1.63** (2.61) .38*** (⫺7.32) .51*** (⫺4.46) .78* (⫺2.00) 1.62** (2.57) .37*** (⫺7.47) .52*** (⫺4.38) .77* (⫺2.15) 1.51* (2.18) .39*** (⫺7.21) .51*** (⫺4.46) .76* (⫺2.23) 1.48* (2.05) .38*** (⫺7.29) .49*** (⫺4.79) .75* (⫺2.32) 1.39* (1.73) .35*** (⫺7.94) .48*** (⫺4.94) .74** (⫺2.41) 1.34⫹ (1.54) .34*** (⫺8.11) .55*** (⫺4.03) .76* (⫺2.18) 1.55* (2.33) .39*** (⫺7.18) .53*** (⫺4.19) .75** (⫺2.37) 1.49* (2.11) .38*** (⫺7.35) .63*** (⫺4.22) .41*** (⫺6.67) 1,571.75 21 4,809 .63*** (⫺4.23) .41*** (⫺6.76) 1,581.11 22 4,809 .63*** (⫺4.29) .42*** (⫺6.87) 1,579.74 21 4,809 .63*** (⫺4.31) .41*** (⫺6.93) 1,581.68 22 4,809 .67*** (⫺3.62) .48*** (⫺5.62) 1,602.09 21 4,809 .67*** (⫺3.67) .47*** (⫺5.66) 1,607.80 22 4,809 .65*** (⫺3.96) .44*** (⫺6.28) 1,592.60 21 4,809 .64*** (⫺4.06) .44*** (⫺6.34) 1,601.88 22 4,809 Note.—Models also control for age. Estimates are presented as odd ratios, and t-values are given in parentheses. ⫹ P ! .10, one-tailed test. * P ! .05, one-tailed test. ** P ! .01, one-tailed test. *** P ! .001, one tailed test. 126 Economic Development and Cultural Change of formal schooling prior to the start of the analysis interval, she had lived outside the neighborhood prior to the analysis interval but not did live outside the neighborhood during the analysis interval, she was Hill Tibetoburmese, and she was born between 1952 and 1961.44 Figure 4 shows that for both boys and girls, the longer a market has been within a 10-minute walk, the greater the likelihood of entering school. However, the number of years a market has been nearby has a stronger effect on entering school for girls than for boys. As markets proliferate (i.e., as the number of years that a market has been within a 10-minute walk increases), the gender gap in school entrance declines because the rate of school entrance for girls rises faster than the rate of school entrance for boys. The interaction terms with school, employment, and transportation service, respectively, have similar effects and can be interpreted in the same way: the spread of each of these has a stronger effect on the rate of school entry for girls than for boys. An examination of the models by gender subgroups confirms this interpretation. In these models (results not shown), the effect of the nonfamily service or organization is either much weaker or insignificant for boys than for girls. Finally, it should be noted that adding an interaction term to the models has virtually no effect on the other coefficients in the models, except for gender, which has a stronger effect in the models with interaction terms than the models without them. B. School Exit Table 3 shows the results of the models of school exit. This table is organized the same way as table 2. We first examine the results for the models without interaction terms. These results provide additional support for our hypothesis that gender influences educational attainment. Gender has a large effect in each of the models, with rates of school exit much lower among boys than girls. Across the first set of models, being male reduces the odds of exiting school in any year by approximately 40%. However, the models of school exit provide only limited support for our hypothesis that local-level social change influences individual-level educational attainment. The number of years that a school has been within a 10minute walk is significant (P ! .05 ), reducing the odds of school exit by 2% per year, and the number of years that a market has been within a 10-minute walk is marginally significant (P ! .10 ), reducing the odds of school exit by 1% per year. However, the number of years that either an employment opportunity or transportation has been within a 10-minute walk is not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the difference in rates of school exit when nonfamily services and organizations have been nearby for a long period of time versus a short period of time is substantively interesting. For example, the difference between living in a neighborhood that has had a school within a 10-minute walk for 25 years and living in a neighborhood that has had a school within a 10-minute walk for 5 years results in a 33% decrease in the annual rate of exiting school (.98 20 p .67). In comparison to the models of school entrance, the family’s educational This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 127 background is somewhat less important in predicting school exit. Across the first set of models, the measure of mother’s father’s education is not significant. The measure of mother’s education, however, has a significant effect in each of the models. Each year of formal schooling a mother has reduces the odds of school exit. As in the models of school entrance, the fixed measure of mother’s migration is not significant. The time-varying measure of migration does have a significant effect in each model, indicating a greater likelihood that (firstborn) children will exit school by age 15, but this effect is marginal. The pattern of effects for religious-ethnic group on school exit mirrors those for school entrance. That is, relative to high-caste Hindus, low-caste Hindus, Hill Tibetoburmese, and Terai Tibetoburmese have higher rates of school exit and Newars have lower rates of school exit. Finally, mother’s birth cohort has a large effect. Women in the two oldest cohorts were much more likely to have firstborn children leave school by age 15 than women in the youngest cohort. Turning to the models that include an interaction term for the nonfamily service or organization and gender of the child, we find little evidence that social change influences the relationship. Only in the model that examines transportation is the interaction term significant. The coefficient of 1.04 in this model indicates that the longer transportation service has been nearby, the less likely girls are to exit school. An examination of the model by gender subgroups (results not shown) indicates that transportation service has a significant negative effect on school exit for girls, but no significant effect on school exit for boys. But overall, the second set of models provides little evidence that local-level social change influences the relationship between gender and school exit. IV. Discussion and Conclusions In keeping with the findings of much previous research, our study shows that gender has an important impact on educational attainment. We find that, unlike boys, girls are much less likely to enter school and much more likely to exit school once they have entered. In contrast to much previous research, however, we also examine whether social change at the community (i.e., local) level influences individual-level educational attainment and whether communitylevel social change influences the relationship between gender and individual educational attainment. While some previous studies have considered the relationship between social change and gender differences in schooling, more often than not these studies have used measures of social change at the national or regional levels. Although this research is useful, it is difficult to understand how changes examined at those levels of analysis influence individual-level decisions to send boys and girls to school. Studies that have examined social characteristics at the community level, the level that is most relevant to individual lives, have used static measures of community characteristics, which makes it difficult to discern the time ordering of the relationship between social change and educational behaviors. The availability of unique data con- This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Discrete-Time Hazards Estimates of the Effects of Gender, Nonfamily Services and Organizations, and Maternal Characteristics on School Exits School 128 This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms TABLE 3 Gender of child (1 p male) Community characteristics: No. of years service or organization within a 10-minute walk No. of years service or organization within a 10-minute walk # gender of child Maternal characteristics: Mother’s father’s education Mother’s education Mother’s migration (fixed) Mother’s migration (time-varying) Employment Market Transportation (1) (2) (1) (2) (1) (2) (1) (2) .58*** (⫺3.81) .51*** (⫺3.46) .59*** (⫺3.70) .56*** (⫺3.74) .59*** (⫺3.74) .53*** (⫺3.65) .59*** (⫺3.71) .52*** (⫺4.05) .98* (⫺1.89) .98* (⫺2.06) .99 (⫺1.15) .98⫹ (⫺1.38) .99⫹ (⫺1.39) .98 (⫺1.70) 1.02 (1.00) .84 (⫺.90) .84*** (⫺4.27) 1.07 (.11) 1.26⫹ (1.38) .83 (⫺.93) .84*** (⫺4.24) 1.08 (.12) 1.28⫹ (1.44) 1.02 (.86) .85 (⫺.82) .84*** (⫺4.20) 1.08 (.12) 1.30⫹ (1.57) .85 (⫺.81) .84*** (⫺4.15) 1.04 (.06) 1.31⫹ (1.60) .99 (⫺.56) 1.02 (1.05) .86 (⫺.77) .84*** (⫺4.15) 1.04 (.06) 1.30⫹ (1.56) .86 (⫺.75) .84*** (⫺4.10) 1.04 (.06) 1.31⫹ (1.60) .98⫹ (⫺1.46) 1.04* (1.69) .85 (⫺.79) .84*** (⫺4.22) 1.08 (.12) 1.28⫹ (1.46) .86 (⫺.78) .84*** (⫺4.19) 1.03 (.04) 1.28⫹ (1.48) Mother’s religiousethnicity (reference p highcaste Hindu): Low-caste Hindu Newar Terai Tibetoburmese Mother’s birth cohort (reference p 1962–71): Born in 1952–61 Born in 1942–51 129 This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Hill Tibetoburmese 2 x Degrees of freedom Person-years (N) 3.53*** (5.95) 1.54* (2.31) .46* (⫺1.96) 3.60*** (6.30) 3.54*** (5.96) 1.54* (2.30) .45* (⫺1.99) 3.61*** (6.31) 3.54*** (5.96) 1.55** (2.34) .46* (⫺1.90) 3.49*** (6.13) 3.59*** (6.01) 1.56** (2.36) .47* (⫺1.89) 3.52*** (6.17) 3.65*** (6.07) 1.55** (2.34) .47* (⫺1.84) 3.64*** (6.34) 3.71*** (6.12) 1.56** (2.37) .48* (⫺1.82) 3.65*** (6.34) 3.50*** (5.90) 1.54* (2.28) .45* (⫺1.99) 3.51*** (6.16) 3.55*** (5.95) 1.56** (2.36) .45* (⫺1.96) 3.55*** (6.21) 1.71** (2.50) 2.77*** (4.37) 260.73 23 7,170 1.70** (2.48) 2.79*** (4.40) 261.72 24 7,170 1.79** (2.73) 3.01*** (4.83) 258.48 23 7,170 1.79** (2.74) 3.06*** (4.87) 259.22 24 7,170 1.77** (2.69) 2.90*** (4.61) 259.09 23 7,170 1.78** (2.71) 2.95*** (4.66) 260.18 24 7,170 1.81** (2.78) 3.05*** (4.84) 257.41 23 7,170 1.83** (2.82) 3.16*** (4.95) 260.26 24 7,170 Note.—Models also control for time. Estimates are presented as odd ratios, and t values are given in parentheses. ⫹ P ! .10, one-tailed test. * P ! .05, one-tailed test. ** P ! .01, one-tailed test. *** P ! .001, one tailed test. 130 Economic Development and Cultural Change taining dynamic measures of community characteristics and individual experiences has allowed us to establish the temporal ordering of communitylevel changes and individual behaviors and, in turn, carefully examine the relationships among gender, social change, and educational attainment. Our results show how examining changes in community characteristics over time enhances our understanding of the relationships among gender, social change, and educational attainment. We find that local-level social change, specifically the spread of nonfamily services and organizations, influences both boys’ and girls’ educational attainment. Moreover, we also find evidence that the spread of nonfamily services and organizations has greater effects on entering school for girls than for boys. This important difference produces a decline in the gender gap in school entry. It seems likely that as the presence and proximity of nonfamily services and organizations increases within a community, gender norms and gender role attitudes change. However, it is important to note that we found little evidence that the spread of nonfamily services and organizations has an impact on the gender gap in school exit. Despite the spread of nonfamily services and organizations, a large gender difference in dropping out of school remains. It may be that gender norms and gender role attitudes first change in ways that promote girls’ entrance into school but not necessarily their continued enrollment in school. In fact, dropping out of school may be a particularly important component of gender differences in attainment as girls age, mature, and near involvement in familybuilding behaviors, such as marriage and childbearing, that may conflict with continued schooling. Along these lines, other data from our survey suggest that the reasons for leaving school are linked to gender roles. Among the mothers in the survey whose children attended school and then quit (before the survey), a similar percentage of male and female children left school because they had failed (24.5% of male children and 24.2% of female children, respectively), but other reasons for leaving school differed considerably by gender. Only 2.4% of male children left because they married, but 32.7% of female children left school for that reason. In contrast, 16.0% of male children left school because of a job, but only 0.7% of female children exited school for that reason. Thus, family formation events appear to be a much more common reason for truncating educational attainment among females in this setting, and work events appear to be a much more common reason for discontinuing education among males. So, even in communities in which female school entry rivals male school entry, family formation events, and societal expectations regarding women’s behaviors and roles within their families still lead females to truncate their education earlier than males. This particular set of findings suggests that our understanding of the relationships among gender, social change, and educational attainment would be further enhanced by using direct and dynamic measures of gender norms and gender role attitudes within communities. Karen Oppenheim Mason has suggested that such measures would be useful for understanding the dynamics This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 131 of change in women’s fertility and mortality.45 They undoubtedly would be useful for understanding the dynamics of change in girls’ and women’s educational participation and attainment as well. Notes * This article was written while the first author was funded by a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development postdoctoral traineeship through the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan (no. HD07339). We wish to thank the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for their generous support of both the data collection and the data analyses reported in this manuscript (no. R01 HD32912). We also wish to thank Jennifer Barber, Dirgha Ghimire, Lisa Pearce, and the staff of the Population and Ecology Research Laboratory for their assistance in gathering the data used in these analyses; Cathy Sun and Lisa Neidert for their work in preparing data files; and Scott Yabiku for his help conducting the analyses. Any errors or omissions remain solely our responsibility. 1. Peter M. Blau and Otis D. Duncan, The American Occupational Structure (New York: Wiley & Sons, 1967); Otis D. Duncan, David L. Featherman, and Beverly Duncan, Socioeconomic Background and Achievement (New York: Seminar, 1972); William H. Sewell and Robert M. Hauser, Education, Occupation, and Earnings: Achievement in the Early Career (New York: Academic Press, 1975); James Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990); Gary S. Becker, Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 3d ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993). 2. William H. Sewell and Vimal P. Shah, “Socioeconomic Status, Intelligence, and the Attainment of Higher Education,” Sociology of Education 40, no. 1 (Winter 1967): 1–23, and “Parents’ Education and Children’s Educational Aspirations and Achievements,” American Sociological Review 33, no. 2 (April 1968): 191–209; Karl L. Alexander and Bruce K. Eckland, “Sex Differences in the Educational Attainment Process,” American Sociological Review 39, no. 5 (October 1974): 668–82; Margaret Mooney Marini, “The Transition to Adulthood: Sex Differences in Educational Attainment and Age at Marriage,” American Sociological Review 43, no. 4 (August 1978): 483–507, and “Sex Differences in the Process of Occupational Attainment: A Closer Look,” Social Science Research 9, no. 4 (December 1980): 307–61. However, in the United States, patterns of educational attainment have changed in recent years such that a higher percentage of young women than young men earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees (U.S. Bureau of the Census, “Educational Attainment in the United States,” Current Population Reports, Series P20-528 [Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2000]). 3. Sewell and Shah, “Parents’ Education and Children’s Educational Aspirations and Achievements,” and “Social Class, Parental Encouragement, and Educational Aspirations,” American Journal of Sociology 73, no. 5 (March 1968): 559–72. Jerry A. Jacobs (“Gender Inequality and Higher Education,” in Annual Review of Sociology, ed. John Hagan [Palo Alto, Calif.: Annual Reviews, 1996], pp. 153–85), citing research by Jere R. Berhman, Robert A. Pollak, and Paul Taubman (“Do Parents Favor Boys?” International Economic Review 27, no. 1 [February 1986]: 33–54) and Robert M. Hauser and Hsiang-Hui Daphne Kuo (“Does the Gender Composition of Sibships Affect Educational Attainment?” Working Paper no. 95-06 [Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin—Madison, July 1997]), notes that, in the contemporary United States, the similar levels of educational attainment among young adult males and females suggest that parents’ educational aspirations do not differ by gender of the child nowadays. 4. Marini, “The Transition to Adulthood, ” and “Sex Differences in the Process of Occupational Attainment.” This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 132 Economic Development and Cultural Change 5. Arland Thornton, Duane F. Alwin, and Donald Camburn, “Causes and Consequences of Sex-Role Attitudes and Attitude Change,” American Sociological Review 48, no. 2 (April 1983): 211–27; S. Philip Morgan and Linda J. Waite, “Parenthood and the Attitudes of Young Adults,” American Sociological Review 52, no. 4 (August 1987): 541–47. 6. Marini, “The Transition to Adulthood”; Ronald R. Rindfuss, C. Gray Swicegood, and Rachel Rosenfeld, “Disorder in the Life Course: How Common Is It, and Does It Matter?” American Sociological Review 52, no. 6 (December 1987): 785–801. 7. Audrey Chapman Smock, Women’s Education in Developing Countries: Opportunities and Outcomes (New York: Praeger, 1981); Dean T. Jamison and Marlaine E. Lockheed, “Participation in Schooling: Determinants and Learning Outcomes in Nepal,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 35, no. 2 (January 1987): 279–306; Elizabeth King, Educating Girls and Women: Investing in Development (Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 1990); M. Anne Hill and Elizabeth M. King, “Women’s Education in Developing Countries: An Overview,” in Women’s Education in Developing Countries: Barriers, Benefits, and Policies, ed. Elizabeth M. King and M. Anne Hill (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), pp. 1–50; United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report, 1999 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). 8. Jamison and Lockheed; Nelly P. Stromquist, “Determinants of Educational Participation and Achievement of Women in the Third World: A Review of the Evidence and a Theoretical Critique,” Review of Educational Research 59, no. 2 (Summer 1989): 143–83. 9. Meena Acharya and Lynn Bennett, The Rural Women of Nepal: An Aggregate Analysis and Summary of Eight Village Studies (Kathmandu: Centre for Economic Development and Administration, 1981); Shrtii Shakti, Women, Development, Democracy: A Study of the Socio-Economic Change in the Status of Women in Nepal, 1981–1993, prepared for USAID, DANIDA, and CCO (Kathmandu: Shtrii Shakti, 1995). 10. Jacqueline A. Ashby, “Equity and Discrimination among Children: Schooling Decisions in Rural Nepal,” Comparative Education Review 29, no. 1 (February 1985): 68–80; Stromquist; Shahrukh R. Khan, “South Asia,” in King and Hill, eds. (n. 7 above), pp. 211–46. 11. Mead Cain, “Risk, Fertility, and Family Planning in a Bangladesh Village,” Studies in Family Planning 11, no. 6 (June 1980): 219–23, “Risk and Insurance: Perspectives on Fertility and Agrarian Change in India and Bangladesh,” Population and Development Review 7, no. 3 (September 1981): 435–74, and “Perspectives on Family and Fertility in Developing Countries,” Population Studies 36, no. 2 (July 1982): 159–75; John C. Caldwell, Theory of Fertility Decline (New York: Academic Press, 1982). 12. Tim Dyson and Mick Moore, “On Kinship Structure, Female Autonomy, and Demographic Behavior in India,” Population and Development Review 9, no. 1 (March 1983): 35–60; Ashby; John C. Caldwell, P. H. Reddy, and Pat Caldwell, “Educational Transition in Rural South India,” Population and Development Review 11, no. 1 (March 1985): 29–51; Jamison and Lockheed. 13. Ashby; Caldwell, Reddy, and Caldwell; Hill and King, “Women’s Education in Developing Countries.” 14. Blau and Duncan; Coleman; Becker (all in n. 1 above). 15. Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (London: Strahan & Cadell, 1776); Coleman. 16. Emile Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society (1933; reprint, New York: Free Press, 1984), p. 257. 17. Ibid., pp. 257–58. 18. Arland Thornton and Thomas E. Fricke, “Social Change and the Family: This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Ann M. Beutel and William G. Axinn 133 Comparative Perspectives from the West, China, and South Asia,” Sociological Forum 2, no. 2 (Fall 1987): 746–79; Arland Thornton and Hui-Seng Lin, Social Change and the Family in Taiwan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994). 19. Caldwell; Ron Lesthaeghe and Chris Wilson, “Modes of Production, Secularization, and the Pace of Fertility Decline in Western Europe, 1870–1930,” in The Decline of Fertility in Europe, ed. Ansley Coale and Susan Cotts Watkins (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986), pp. 261–92. 20. William F. Ogburn and Meyer F. Nimkoff, Technology and the Changing Family (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1955); Thornton and Fricke. 21. Prior to the 1950s, education that did take place outside the family was largely in the form of religious training at Buddhist monasteries or Sanskrit schools. In addition, some Nepalis were formally educated at Indian schools (Dor Bahadur Bista, Fatalism and Development: Nepal’s Struggle for Modernization [Calcutta: Orient Longman, 1991]). But for the vast majority of Nepalis, education took place within the family. 22. W. D. Halls, “United Kingdom: System of Education,” in The International Encyclopedia of Education, 2d ed., ed. Torsten Husén and T. Neville Postlethwaite (New York: Pergamon, 1994), 11:6515–23; Kim P. Sebaly, “Nepal,” in World Education Encyclopedia, ed. George Thomas Kurian (New York: Facts on File, 1988), 2: 904–10. However, the structure of primary and secondary levels of education in Nepal has changed several times (T. R. Khaniya and M. A. Kiernan, “Nepal: System of Education,” in The International Encyclopedia of Education, 2d ed., ed. Torsten Husén and T. Neville Postlethwaite [New York: Pergamon, 1994], 7:4060–67). Currently, the primary level is made up of grades 1–5, the lower secondary level of grades 6–8, the secondary level of grades 9–10, and the higher secondary level—a relatively recent innovation—of grades 11–12. Students may enter the higher secondary level if they successfully pass the school leaving certificate (SLC) examination at the end of grade 10. Ten-year school graduates can earn a university degree after 5 years of study, while 12-year school graduates can earn one after 3 years of study (Nepal South Asia Centre, Nepal Human Development Report, 1998 [Kathmandu: Nepal South Asia Centre, 1998]). 23. United Nations, The World’s Women, 1995: Trends and Statistics (New York: United Nations, 1995). 24. Ibid. 25. Nepal South Asia Centre. 26. These methods are described in detail elsewhere—see William G. Axinn, Jennifer S. Barber, and Dirgha J. Ghimire, “The Neighborhood History Calendar: A Data Collection Method Designed for Dynamic Multilevel Modeling,” in Sociological Methodology, ed. Adrian E. Raftery (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1997), pp. 355–92. 27. Nepal South Asia Centre. 28. Shakti (n. 9 above). 29. Axinn, Barber, and Ghimire. 30. For a detailed description, see William G. Axinn, Lisa D. Pearce, and Dirgha J. Ghimire, “Innovations in Life History Calendar Applications,” Social Science Research 28, no. 3 (September 1999): 243–64. 31. Axinn, Barber, and Ghimire. 32. Of course, with these data, calculation of any other distance threshold is equally straightforward. Therefore, we reestimated our models using a variety of different distance thresholds. Use of other distances, such as the number of years that nonfamily organizations and services were within a 5-minute walk, did not appreciably affect our results. 33. For example, Blau and Duncan (n. 1 above). 34. William H. Sewell, Archibald O. Haller, and Alejandro Portes, “The Educational and Early Occupational Attainment Process,” American Sociological Review This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 134 Economic Development and Cultural Change 34, no. 1 (February 1969): 82–92; William H. Sewell, Archibald O. Haller, and George W. Ohlendorf, “The Educational and Early Occupational Status Attainment Process: Replication and Revision,” American Sociological Review 35, no. 6 (December 1970): 1014–27; Sewell and Hauser (n. 1 above). 35. Nan Lin and Daniel Yauger, “The Process of Occupational Status Attainment: A Preliminary Cross-National Comparison,” American Journal of Sociology 81, no. 3 (November 1975): 543–62; Jonathan Kelly, Robert V. Robinson, and Herbert S. Klein, “A Theory of Social Mobility with Data on Status Attainment in a Peasant Society,” in Research in Social Stratification and Mobility: A Research Annual, ed. Donald J. Treiman and Robert V. Robinson (Greenwich, Conn.: JAI, 1981), pp. 27–66; Donald J. Treiman and Kin-Bor Yip, “Educational and Occupational Attainments in 21 Countries,” in Cross-National Research in Sociology, ed. Melvin L. Kohn (Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage, 1989), pp. 373–94. 36. For a summary of studies, see Hill and King, “Women’s Education in Developing Countries” (n. 7. above). 37. Ibid. 38. We also estimated models containing a second measure of mother’s education, which was a time-varying measure of the number of years of education she received during the analysis interval—i.e., starting from when her firstborn was 3 years of age in the school entrance analysis and starting from the year her firstborn entered school in the exit analysis. Models containing the time-varying measure of mother’s education produced results virtually identical to the ones reported here. 39. Robin Stryker, “Religio-ethnic Effects on Attainments in the Early Career,” American Sociological Review 46, no. 2 (April 1981): 212–31. 40. Ashby (n. 10 above); Jamison and Lockheed (n. 7 above). 41. Alternative controls for migration, such as deleting respondents who experienced any migration or deleting those person-years when migration occurred, produced estimates nearly identical to those presented here. 42. Paul D. Allison, “Discrete-Time Methods for the Analysis of Event Histories,” in Sociological Methodology, ed. Samuel Leinhardt (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1982), pp. 61–98, and Event History Analysis: Regression for Longitudinal Event Data (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage, 1984); Trond Petersen, “Estimating Fully Parametric Hazard Rate Models with Time-Dependent Covariates: Use of Maximum Likelihood,” Sociological Methods and Research 14, no. 3 (February 1986): 219–46, and “The Statistical Analysis of Event Histories,” Sociological Methods and Research 19, no. 3 (February 1991): 270–323. 43. Although there are substantial positive correlations among measures of community change over time, we also estimated models of school entrance and exit including all community-level measures of social change in a single model. As one might expect, we found that the effects of the nonfamily services and organizations were substantially attenuated when all were included in the same model. However, because our aim is to evaluate the total impact of each dimension of social change, we present separate models for each measure of social change in the tables. 44. The negative values on the y-axis of fig. 4 are an artifact of the values of control variables used to calculate the predicted values displayed in fig. 4. The predicted values themselves have no substantive interpretation—we display fig. 4 to highlight the difference in slopes between the male and female effects. 45. Karen Oppenheim Mason, “Conceptualizing and Measuring Women’s Status” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Miami, April 1994). This content downloaded from 144.122.207.25 on Tue, 03 Jan 2023 15:22:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms