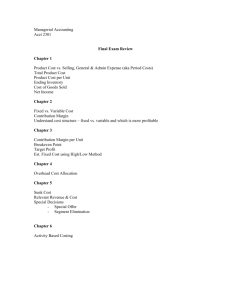

![[Susan V. Crosson, Belverd E. Needles] Managerial (b-ok.org)](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/026324203_1-6437facc3d2acca84ee483c74bb2d477-768x994.png)