Filipino National Living Treasures Award: Artists & Traditions

advertisement

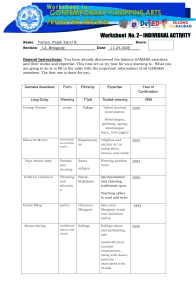

Overview The Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan, or the National Living Treasures Award, is conferred on Filipinos who are at the forefront of the practice, preservation, and promotion of the nation’s traditional folk arts. This module will introduce you about different National Living Treasures Awards SAMAON SULAIMAN (+ 2011) Musician Maguindanao Mamasa Pano, Maguindanao 1993 • • • • • • Learning to play the kutyapi from his uncle when he was about 13 years old. At 35 become the most acclaimed kutyapi master and teacher of his instrument in Libutan and other barangays of Maganoy town, deeply influencing the other acknowledged experts in kutyapi in the area, such as Esmael Ahmad, Bitul Sulaiman, Nguda Latip, Ali Ahmad and Tukal Nanalon. The Maguindanao kutyapi is one of the most technically demanding and difficult to master among Filipino traditional instruments, which is one reason why the younger generation is not too keen to learn it. Of its two strings, one provides the rhythmic drone, while the other has movable frets that allow melodies to be played in two sets of pentatonic scales, one containing semitones, the other containing none. Maguindanao kutyapı music is rich in melodic and rhythmic invention explores a wide range of timbres and sound phenomena - both human and natural, possesses a subtle and variable tuning system, and is deeply poetic in inspiration. Though it is the kulintang that is most popular among the Magindanaon, it is the kutyapi that captivates with its intimate, meditative, almost mystical charm. MASINO INTARAY (+ 2013) Musician and Storyteller, Pala'wan Brookes Point, Palawan 1993 • Masino is an outstanding master of the basal, kulilal and bagit, a gifted poet, bard artist, and musician who was born near the head of the river in Makagwa valley on the foothill of Mantalingayan mountain. • • • • • Masino is not only well-versed in the instruments and traditions of the basal, kulilal, and bagit but also plays the aroding (mouth harp) and babarak (ring flute) and above all is a prolific and pre-eminent epic chanter and story teller. He has the creative memory, endurance, clarity of intellect and spiritual purpose that enable him to chant all through the night, for successive nights, countless tultul (epics), sudsungit (narratives), and tuturan (myths of origin and teachings of ancestors). Masino is an outstanding master of the basal, kulilal and bagit, a gifted poet, bard artist, and musician who was born near the head of the river in Makagwa valley on the foothill of Mantalingayan mountain. Masino is not only well-versed in the instruments and traditions of the basal, kulilal, and bagit but also plays the aroding (mouth harp) and babarak (ring flute) and above all is a prolific and pre-eminent epic chanter and story teller. He has the creative memory, endurance, clarity of intellect and spiritual purpose that enable him to chant all through the night, for successive nights, countless tultul (epics), sudsungit (narratives), and tuturan (myths of origin and teachings of ancestors). GINAW BILOG (+ 2003) Poet, Hanunuo Mangyan Panaytayan, Oriental Mindoro 1993 • • • • A common cultural aspect among cultural communities nationwide is the oral tradition characterized by poetic verses which are either sung or chanted. what distinguishes the rich Mangyan literary tradition from others is the ambahan a poetic literary form composed of seven-syllable lines used to convey messages through metaphors and images. The ambahan is sung and its messages range from courtship, giving advice to the young, asking for a place to stay, saying goodbye to a dear friend and so on. Ambahan has remained in existence today chiefly because it is etched on bamboo tubes using ancient Southeast Asian, pre-colonial script called surat Mangyan. LANG DULAY (+2015) Textile Weaver T'boli Lake Sebu, South Cotabato 1998 • • • Using abaca fibers as fine as hair, Lang Dulay speaks more eloquently than words can. Images from the distant past of her people, the T'bolis, are recreated by her nimble hands --the crocodiles, butterflies, and flowers, along with mountains and streams, of Lake Sebu, South Cotabato, where she and her ancestors were born-fill the fabric with their longing to be remembered. Through her weaving, Lang Dulay does what she can to keep her people's tradition alive. SALINTA MONON (+2009) Textile Weaver Tagabawa Bagobo Bansalan, Davao del Sur 1998 • All her life she has woven continuously, through her marriage and six pregnancies, and even after her husband's death 20 years ago. • She and her sister are the only remaining Bagobo weavers in her community. Her husband paid her parents a higher bride price because of her weaving skills. DARHATA SAWABI (2005) Textile Weaver Tausug Parang, Sulu 2004 • • • • • • • Darharta Sawabi is one of those who took the art of pis syabit making to heart. The families in her native Parang still depend on subsistence farming as their main source of income But farming does not bring in enough money to support a family and is not even an option for someone like Darhata Sawabi who was raised from birth to do only household chores. She has never married. Thus, weaving is her only possible source of income. The money she earns from making the colorful squares of cloth has enabled her to become self-sufficient and less dependent on her nephews and nieces. A hand-woven square measuring 39 by 40 inches, which takes her some three months to weave, brines her about P2000. MAGDALENA GAMAYO Textile Weaver Ilocano Pinili, Ilocos Norte 2012 • The Ilocos Norte that Magdalena Gamayo knows is only a couple of hours drive away from the capital of Laoag but is far removed from the quickening pulse of the emergent city. • Instead, it remains a quiet rural enclave dedicated to rice, cotton, and tobacco crops. • 2012 Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan awardee, Magdalena Gamayo still owes a lot to the land and the annual harvest. Despite her status as a master weaver, weaving alone is not enough. Also, even though the roads are much improved, sourcing quality cotton threads for her abel is still a challenge. Even though the North is known for its cotton, it does not have thread factories to spin bales of cotton into spools of thread. Instead, Magdalena has to rely on local merchants with their limited supplies. TEOFILO GARCIA Casque Maker Ilocano San Quintin, Abra 2012 • Each time Teofilo Garcia leaves his farm in San Quintin, Abra, he makes it a point to wear a labungaw. • People in the nearby towns of the province, in neighboring Sta. Maria and Vigan in Ilocos Sur, and as far as Laoag in Ilocos Norte, sit up and take notice of his unique functional and elegant headpiece that shields him from the rain and the sun. • A closer look would reveal that it is made of the native gourd, hollowed out, polished, and varnished to a bright orange sheen to improve its weather resistance. • The inside is lined with finely woven rattan matting, and the brim sports a subtle bamboo weave for accent • Because he takes pride in wearing his creations, Teofilo has gotten many orders a result. • Through his own efforts, through word of mouth, and through his participation in an annual harvest festival in his local Abra, a lot of people have discovered about the wonders of the tabungaw as a practical alternative. • Hundreds have sought him out at his home to order their own native all-weather headgear. • His clients have worn his work, sent them as gifts to their relatives abroad and showed them off as a masterpiece of Filipino craftsmanship. • With the proper care, a well-made tabungaw can last up to three to four generations. • • ALONZO SACLAG Musician and Dancer Kalinga Lubuagan, Kalinga 2000 • A Kalinga Master of Dance and the performing arts, he has made it his mission to create and nurture a greater consciousness and appreciation of Kalinga culture, among the Kalinga themselves and beyond their borders. • As a young boy in Lubuagan, Kalinga, Alonzo Saclag found endless fascination in the sights and sounds of day-to day village life and ritual. • According to his son, Robinson, he received no instruction, formal or otherwise, in the performing arts. • Yet he has mastered not only the Kalinga musical instruments but also the dance patterns and movements associated with his people's rituals. • His tool was observation, his teacher is experience coupled with these was a keen interest in-a passion if you would-the culture that was his inheritance. This passion he clearly intends to pass on to the other members of his community, particularly to the younger generation which, he notes, needs to understand and value the nuances of their traditional laws and beliefs. Although Kalinga life and culture have remained generally unchanged partly due to their relative isolation, he observes that some of them are tempted by the illusion of city life. EDUARDO MUTUC Metalsmith Kapampangan Apalit, Pampanga 2004 • • • • • • • • • Eduardo Mutuc is an artist who has dedicated his life to creating religious and secular art in silver, bronze and wood. • His intricately detailed retablos, mirrors, altars, and carosas are in churches and private collections. A number of these works are quite large, some exceeding forty feet while some are very small and feature very fine and delicate craftsmanship. • For an artist whose work graces cathedrals and churches, Mutuc works in humble surroundings. His studio occupies a corner of his yard and shares space with a tailoring shop. • During the recent rains, the river beside his lot overflowed and water flooded his studio in Apalit, Pampanga, drenching his woodblocks. • Mutuc takes it all in stride. He discovered his talents in sculpture and metalwork quite late. He was 29 when he decided to supplement his income from farming for the relatively more secure job of woodcarving. • He spent his first year as an apprentice to carvers of household furniture. It was difficult at the beginning, but thanks to his mentors, he was able to develop valuable skills that would serve him in good stead later on. The hardest challenge for him was learning a profession that he had no prior knowledge about, but poverty was a powerful motivation. Although his daily wage of P3.00 didn't go far to support his wife and the first three of nine children (one of whom has already died), choices were limited for a man who only finished elementary school. Things began to change after his fifth or sixth year as a furniture maker when a colleague taught him the art of silver plating. This technique is often used to emulate gold and silver leaf in the decoration of saints and religious screens found in colonial churches. FEDERICO CABALLERO Epic Chanter Sulod-Bukidnon Calinog, Iloilo 2000 • Federico Caballero, from the mountains of Central Panay ceaselessly work for the documentation of the oral literature particularly the epics, of his people. • These ten epics, rendered in a language that, although related to Kiniray-a, is no longer spoken, constitute an encyclopedic folklore one only the most persevering and the most gifted of disciples can learn. • Together with scholars, artists, and advocates of culture, he painstakingly pieces together the elements of this oral tradition nearly lost. His own love for his people's folklore began when he was a small child. • His mother would lull his brothers and sister to sleep, chanting an episode in time to the gentle swaying of the hammock. Sometimes it was his great-great-grandmother, his Anggoy Omil, who would chant the epics. Nong Pedring remembers how he would press against them as they cuddled his younger siblings, his imagination recreating the heroes and beautiful maidens of their tales. In his mind, Labaw Dunggon and Humadapnon grew into mythical proportions, heroes as real as the earth on which their hut stood and the river that nourished it. Each night he learned more about where their adventures brought them. be it to enchanted caves peopled by charmed folk or the underworld to rescue an unwitting prisoner from the clutches of an evil being And the more he learned, the greater his fascination became. When his mother or his Anggoy would inadvertently nod off, he would beg them to stay awake and finish the tale. His fascination naturally grew into a desire to learn to chant the epics himself. Spurred on by this, he showed an almost enterprising facet: when asked by his Anggoy to fetch water from the river, pound rice, or pull grass from the kaingin, he would agree to do so on the condition that he be taught to chant an epic Such audacity could very well have earned him a scolding. But it was his earnestness that clearly shone through. Not long after, he conquered all ten epics and other forms of oral literature, besides. When both his Anggoy and his mother had passed on Nong Pedring continued the tradition, collaborating with researchers to document what is customarily referred to as Humadapnon and Labaw Dunggon epics. Although his siblings also share the gift of their forebears, he alone persevered in the task, unmindful of the disapproval of his three children He explains that like a number of people in their community, they find no pride in claiming their Panay-Bukidnon heritage UWANG AHADAS Musician Yakan Lamitan, Basilan 2000 • Uwang Ahadas is a Yakan, a people to whom instrumental music is of much significance, connected as it is with both the agricultural cycle and the social realm. • One old agricultural tradition involves the kwintangan kayu, an instrument consisting of five wooden logs hung horizontally, from the shortest to the longest, with the shortest being nearest the ground. After the planting of the rice, an unroofed platform is built high in the branches of a tree. • Then the kwintangan kayu is played to serenade the palay, as a lover woos his beloved. Its resonance is believed to gently caress the plants, rousing them from their deep sleep, encouraging them to grow and yield more fruit • With this heritage, as rich as it is steeped in music it is no wonder that even as a young child, Uwang joyously embraced the demands and the discipline necessitated by his art. • His training began with the ardent observation of the older, more knowledgeable players in his community. His own family, gifted with a strong tradition in music, complemented the instruction he received. • He and his siblings were all encouraged to learn how to play the different Yakan instruments, as these were part of the legacy of his ancestors. • Not all Yakan children have such privilege. Maintaining the instruments is very expensive work and sadly, there is always the temptation presented by antique dealers and other collectors who rarely, if at all, appreciate the history embodied in these artifacts. • From the gabbang, a bamboo xylophone, his skills gradually allowed him to progress to the agung, the kwintangan kayu, and later the other instruments. Even musical tradition failed to be a deterrent to his will. Or perhaps it only served to fuel his determination to demonstrate his gift. Yakan tradition sets the kwintangan as a woman's instrument and the agung, a man's. • His genius and his resolve, however, broke through this tradition. By the age of twenty, he had mastered the most important of the Yakan musical instruments, the kumtangan among them. Uwang, however, is not content with merely his own expertise. • He dreams that many more of his people will discover and study his art. With missionary fervor, he strives to pass on his knowledge to others. • His own experience serves as a guide. He believes it is best for children to commence training young when interest is at its peak and flexibility of the hands and the wrists are assured. His own children were the first to benefit from his instruction. • One of his daughters, Darna, has become quite proficient in the art that like her father, she too has begun to train others. His purpose carries him beyond the borders of Lamitan to the other towns of Basilan where Uwang always finds a warm welcome from students, young and old, who eagerly await his coming. • His many travels have blessed him with close and enduring ties with these people. Many of his onetime apprentices have come into their own have gained individual renown in the Yakan community. He declares, with great pride, that they are frequently invited to perform during the many rituals and festivals that mark the community calendar