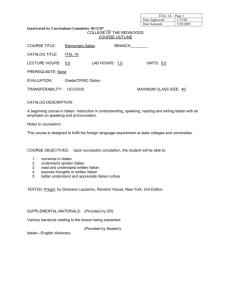

Italian All-in-One For Dummies: Language Textbook

advertisement