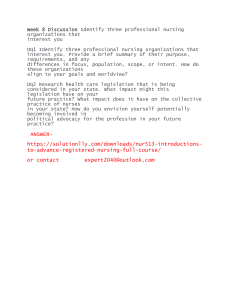

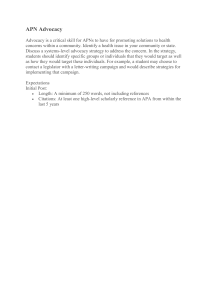

EMPIRICAL STUDIES doi: 10.1111/scs.12505 A practice model for rural district nursing success in end-of-life advocacy care Frances M. Reed RN BN (hons) HC H (G Nurs.) HC HPPC (PhD Student) , Les Fitzgerald RN RM Dip. Teach Nurs B.Ed. MNurs. Stud. PhD (Senior Lecturer) and Melanie R. Bish RN BN (hons) BCN MN PhD (Head of Department) La Trobe School of Rural Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Bendigo, Victoria, Australia Scand J Caring Sci; 2018; 32; 746–755 A practice model for rural district nursing success in end-of-life advocacy care Aim: The development of a practice model for rural district nursing successful end-of-life advocacy care. Background: Resources to help people live well in the end stages of life in rural areas can be limited and difficult to access. District nurse advocacy may promote end-of-life choice for people living at home in rural Australia. The lack of evidence available internationally to inform practice in this context was addressed by exploratory study. Method: A pragmatic mixed method study approved by the University Faculty Ethics Committee and conducted from March 2014 to August 2015 was used to explore the successful end-of-life advocacy of 98 rural Australian district nurses. The findings and results were integrated then compared with theory in this article to develop concepts for a practice model. Results: The model illustrates rural district nurse advocacy success based on respect for the rights and values of people. Advocacy action is motivated by the emotional responses of nurses to the end-of-life vulnerability people experience. The combination of willing investment in Introduction Personal rights and equitable access to services are at the forefront of international health policy directing care in the end stages of life (1, 2). A focus on the values and rights of individuals and their family carers may improve the experiences of people both giving and receiving endof-life care (3–5). In this context, end-of-life (EoL) care refers to care provided for people affected by life-limiting illness or disability (3). Effort is particularly needed to plan and provide for care choices when people may be Correspondence to: Frances M. Reed, La Trobe School of Rural Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Bendigo, Victoria, Australia. E-mail: fmreed@students.latrobe.edu.au 746 relationships, knowing the rural people and resources, and feeling supported, together enables district nurses to develop therapeutic emotional intelligence. This skill promotes moral agency in reflection and advocacy action to overcome emotional and ethical care challenges of access and choice using holistic assessment, communication, organisation of resources and empowering support for the self-determination of person-centred end-of-life goals. Recommendations are proposed from the theoretical concepts in the model. Limitations: Testing the model in practice is recommended to gain the perceptions of a broader range of rural people both giving and receiving end-of-life-care. Conclusion: A model developed by gathering and comparing district nursing experiences and understanding using mixed methods and existing theory offers evidence for practice of a philosophy of successful person-centred advocacy care in a field of nursing that lacks specific guidance. Keywords: advocacy care, end-of-life, community, district nurse, emotion, moral agency, palliative care, practice model, rural. Submitted 18 May 2017, Accepted 20 June 2017 vulnerable to EoL changes that threaten their rights and values. Background To meet the needs of an ageing population, greater support and easier access to effective primary health care in the home setting are proposed by the Australian Government (6, 7). Australia is made up of vast, sparsely populated remote areas, small, heavily populated urban areas and large rural regions where almost one-third of the population live (8). In rural regions, many people approaching the EoL are affected by socio-economic and geographical barriers that limit access to services and reduce the availability of supportive and specialist care (8). © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science A practice model for successful advocacy Nurses caring for people living and dying at home in rural areas expand their generalist primary healthcare roles to reduce service gaps (9–11). Commonly referred to as community or district nurses (DNs) in Australia, these nurses cover large areas delivering care to people with diverse needs (11). The rising demand for complex care for people living at home increases the pressure on DN services with limited resources to focus on the medical interventions they provide (11, 12). This may affect care satisfaction by reducing time spent in therapeutic relationship development and teamwork (9, 13). To create greater opportunity for choice and well-being in rural areas, DNs need to advocate for access to person-centred EoL care (14). This requires a focus on the holistic needs of individuals, families and their community of informal and formal caregivers (14). Promoted internationally for ethical care provision (15), nursing advocacy remains a poorly understood concept that has not previously been explored in rural home nursing. This lack of specific evidence-based knowledge prompted exploration of experiences that could inform a model to guide the practice of rural DNs in successful EoL advocacy (14, 16). Practice guidance can be used by services to promote DN advocacy and improve opportunities for choice and the well-being of rural people whilst living at home in the end stages of life. Method and results Aim The aim is to develop a practice model from a study exploring how DNs advocate successfully for the end-oflife goals of rural Australians and a comparison with existing theory. Ethical approval The study was approved by the University Ethics Committee, and further approvals were gained when required by specific organisations. Design The sequential mixed methods study used a pragmatic philosophy and nurse agency theory (17). Pragmatism offers a framework for studying complex problems using a mix of study methods to provide credible evidence for practice (17, 18). Dewey’s philosophy of pragmatism promotes the agency of people to reflect intelligently on the wide range and sources of knowledge and the possible outcomes of action (18). Nurse agency refers to the reflection–action process that promotes effective care (19). The use of a flexible, iterative mix of methods acknowledges the multiple facets of understanding and © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science 747 the need for practical, ethical solutions that fit the complexity of rural practice situations (18). The opportunity given to DNs to reflect on the ways they understand and action advocacy promoted their agency in the exploration of successful EoL care experiences (17). Nursing advocacy was defined for the study as action taken to support the health goals of people at the levels of the person, the community and the health system (20). The purposive self-selection criteria for the study sample included Registered Nurses with experience in providing successful EoL advocacy in rural generalist home care roles. In the first qualitative phase, DNs from rural Victoria, Australia (N = 7), provided reflective written experiences of successful advocacy before taking part in follow-up semi-structured 1 hour interviews, between July and September 2014 (21). Participants were asked to reflect and write about one successful advocacy experience (21). The information pack included a written example from a different field of practice to indicate the detail required (21). Reflective questions arising from the written examples and an interview guide developed from a review of DN EoL care studies were used to explore advocacy experiences in the follow-up interviews (14, 21). The combination of qualitative written and interview narrative techniques increased the understanding and scope of the data (21). Data analysis was iterative, beginning with reflection on the written experiences in the first phase to inform the interviews (21). Descriptive interpretation was facilitated by coding the written and interview transcripts in NVivo QRS 10 to produce thematic networks that explain how successful advocacy is enabled and actioned (21, 22). The thematic description was confirmed by the informants, then tested and complemented using a survey for the second study phase. The survey was designed with a questionnaire that included psychometric scales and open-ended question. Two scales were developed using items identified from the qualitative data: the first scale to test how advocacy is enabled, and the second scale to test how advocacy is actioned in rural EoL DN. Open-ended questions explored concepts, which required clarification, and provided the opportunity to add alternate views. The Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale (BEIS10) developed by Davies et al. (23) tested the findings of emotional care ability identified in the qualitative phase. Piloting of the survey assisted refinement and re-ordering of the scale items to improve the response quality. Email invitations to participate sent to health services in rural regions of Australia from March to August 2015 included an online link to the survey available using Qualtrics (24). Some services required further ethical approval prior to offering the survey to nurses. The responses (N = 91) came from each State and Territory, except Queensland, where ethical approval could not be gained within the survey timeline. 748 F. M. Reed et al. The results of the survey were analysed using quantitative and qualitative methods. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSSâ) IBM Windows version 21 generated descriptive statistics from the scale responses. The qualitative answers to the open-ended questions were coded to assess fit and identify additional understanding of the Phase 1 themes. The results confirmed and complemented the Phase 1 findings, further validating the interpretative description of successful DN EoL advocacy for the goals of rural Australians (21). In the final stage of the study, the findings and results from both phases were integrated in thematic inferences (18). These inferences were compared with nursing literature to identify similarities and new understandings in how advocacy is enabled, and actioned successfully in the home care setting. The comparison provided further confirmation that the inferences were suitable for use as concepts to build a practice model representing the process that enables advocacy development and action, and leads to success. Results and discussion A practice model for rural DN success in end-of-life advocacy The theoretical concepts informed by the study together represent the practice of nursing advocacy as a learned philosophy of care. The concepts originated from the qualitative exploration and analysis during the first phase of study (21) and were confirmed and complemented by the qualitative and quantitative results in the second phase. Examples of data from each phase are provided in Table 1 to indicate how the concepts were informed and validated. These concepts are used in a hierarchical process model of practice that illustrates how DNs advocate successfully for the EoL goals of rural Australians (Fig. 1). Development of the therapeutic self for advocacy Respect. Successful end-of-life advocacy care is founded on the concept of respect for the rights and diverse values of all people. DNs who practice this ‘respect’ (Table 1) can recognise the vulnerability people experience to loss of rights and lack of support for values in the end stages of life (25–29). Identifying this type of vulnerability in people arouses emotions of empathy and sympathy that work together to drive nursing action (29). These emotional responses motivate DNs to develop the ability for advocacy, which is enabled by being willing to invest in person-centred care, knowing the people and feeling supported (21). Willing. The concept of being ‘willing’ identifies DNs who are prepared to invest effort in respectful personcentred relationships (21, p. 7). Being willing to use the SUCCESSFUL End-of-life Nurse Advocacy Care for personcentred goals Sasfacon Provision of Support Empowering people Organising Resources Communicaon at all levels Holisc assessment Promoon of Access to rural resources for choice at mulple levels Posive Outcomes Barriers Risks MORAL AGENCY A process of reflecon that morally guides advocacy acon to successfully overcome barriers to choice EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE The learned ability to recognize, understand and manage emoon in one-self and others WILLING SUPPORTED KNOWING investment in by self-advocacy, the rural people person centred experience, care using the at home, educaon, Empathy autonomy the self, the Sympathy systems of health available, community and care and emoonal energy the resources and involvement informaon, and available with people other people Recognion of the VULNERABILTY people experience to loss of self-determinaon and lack of support for values RESPECT for all PEOPLE and their rights and values Figure 1 A practice model for rural district nursing success in end-of-life advocacy care. © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science A practice model for successful advocacy autonomy inherent in home care offers DNs freedom to respond to feelings with supportive relationship care. DNs with a preparedness to invest the time and emotional energy required to become involved in personalised caring can give of the self to accommodate the needs of people and their family (21). Respectful consideration of feelings, emotions and values enables DNs to personalise therapeutic relationships. The willingness to be involved with people and their EoL experiences promotes reciprocated trusting relationships and the sharing of information for person-centred care (19, 21). Willing ‘involvement’ provides opportunities for advocacy that can meet the needs of the people (21, 26) (Table 1). Knowing. The concept of ‘knowing’ identifies the specialised knowledge DNs possess about rural people, their circumstances and the available community resources (21, p. 7) (Table 1). A personal way of knowing oneself and others is informed by working with, and being involved with people. DNs reflect with self-understanding of personal values and reactions that affect interprofessional and EoL nursing relationships (21, 26). Self-knowing combines with knowing people and the ‘circumstances’ in their homes to instil a deeper sense of the prevailing moods that influence personal reactions. Insight into the meaning that each person attributes to life provides the aesthetic knowledge to intuitively refine nursing relationships (21) (Table 1). Reflection on the values of self and others informs ethical care to help people identify their end-of-life goals. Combined with the experience of rural living and work, these ways of knowing inform the adaptation of nursing practice to suit the particular social determinants of health and the individual meaning of EoL experiences and situations (16, 21). DNs bring the ways of knowing together in advocating for a person-centred approach to EoL care. Knowing the social and environmental context of the person’s life and relationships offers greater insight into the threats to selfdetermination. Knowing the people involved in giving and receiving care, recognising the effect of their values, emotions, reactions, relationships and the environment, and understanding how to access the limited resources can enable EoL planning (16, 21). This holistic knowledge increases ‘intuition’ in a situated way of knowing to inform the development of personalised therapeutic advocacy and convey respect for person-centred goals (21) (Table 1). Supported. Feeling ‘supported’ whilst working as a sole practitioner with limited resources is the third enabler of person-centred advocacy (21, p. 8). Support is found in two forms: self-advocacy and the respect received from others. DNs prepare and equip the self for advocacy using a combination of ‘education’, ‘experience’, reflective © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science 749 practice and ‘self-care’ that promote ability for a competent personal response to EoL needs (20, 21) (Table 1). The resulting self-reliance DNs develop as advocates is enhanced by health system resources. These include ‘policies’, ‘care plans’ and information to facilitate personalised health promotion and goal setting, together with the technology to access information, education and communication (21) (Table 1). DNs are encouraged in personal advocacy efforts by the respect of others for the knowledge acquired with person-centred care (21). Advocacy for individual rights and values is strengthened by trusted informal and formal support networks, which may include family, friends, ‘colleagues’, ‘managers’ and other health professionals (Table 1). Feeling supported by these people increases self-confidence in the ability to assess situations and take action to promote individual EoL goals that may conflict with dominant cultures. This support encourages DNs to stand by the person when there is dissent resulting from competing values affecting the situation (21). Taking a justifiable stand that may be at odds with the beliefs of others requires courage in the conviction that person-centred care for EoL goals is a priority. DNs feel validated as advocates when the privileged understanding gained by working closely with people in their homes is acknowledged. Emotional intelligence. The combination of respect, willing, knowing and supported underpins the emotional skill development of DNs for person-centred EoL advocacy (21). The development of emotional intelligence increases the ability to recognise, understand and manage the emotions of self and others (30). Critical reflection on the feelings and understandings about the people and situations DNs encounter assists the navigation of involvement in EoL relationships that provide ‘emotional support’ for person-centred goals (Table 1). DNs who develop emotional intelligence are able to give more of self in the therapeutic use of emotions to improve the experience of EoL care (19, 26). This ability enables DNs to manage personal reactions in the emotional care of people; identify the degree of involvement required in nursing relationships (31); and understand the impact of emotions on the values of others involved in care (21). The resulting consideration for the effect of emotions on possibilities for choice in each situation assists DNs to act as moral agents (21). Moral agency. Emotional intelligence is a prerequisite for the moral agency of DNs in EoL advocacy. A moral agent attends, reflects and takes action based on respect and understanding of the person’s wishes (32). The moral response of ‘reflection’ on action from DNs in rural EoL care is required to negotiate the risks and barriers to advocacy for self-determination (Table 1). The lack of Support ‘We need to try and support. . .’ (1) Support peers 100% Support the person/family 97% Defending rights 96% Empowerment of the person/family 100% Enabling self-determination 94% Phase 1 For a detailed description of findings see Author Reed et al. 2016 (21). Phase 2 The examples given in percentages represent the full range of agreement resulting from all the scale items. Empowerment ‘. . .she felt so empowered. . .’ (3) Communication ‘document these goals so all can follow’ (5) Organisation Holistic assessment 100% Identifying person and family goals 100% Documenting/sharing goals 100% Talk/plan for dying 100% Teaching care 100% Case managing/liaising with others 100% Planning care 100% Providing equipment 100% Holistic assessment ‘. . .having a family meeting’ (6) ‘It was me, from here, that organised it all’ (2) Promoting quality care/collaboration on a broader scale 99% Access Emotional intelligence Moral agency ‘. . .energy and emotion. . .’ (2) ‘mindfulness in that moment with them’ (3) ‘. . .trying to get it right’ (3) ‘. . .looking at it from the other side’ (5) ‘. . .judging if my advocacy. . .’ (6) ‘. . . try and show that there is another way to look at things’ (4) ‘. . .it’s a lot about the whole collective situation’ (2) ‘. . .asking what they want to do’ (1) Supported ‘. . .protective self-care’ (6) ‘. . .teleconferences’ (3) ‘. . .my boss is good with palliative care’ (7) ‘I was brought up to respect people’ (7) Trying hard 99% Being flexible 99% I feel good about giving EoL care 87% Making time, giving self, going beyond duty 52% Willing Knowing the person’s end-of life goals 100% Knowing self and abilities 92% Knowing the person/family 98% Intuitive knowing 75% Being able to inform/support oneself 98% Education 99% Experience 99% Documents, policies, care plans 85% Support from other health professionals 98% BEIS scale (10 items total) 84% Respect for individual differences 100% Phase 2 Quantitative/qualitative Psychometric scale items and agreement percent Respect Knowing ADVOCACY ENABLERS AND ACTIONS Concept ‘knowing and understanding what’s important to them’ (6) ‘. . .thinking’ . . . (3) ‘belief in your experience’ (1) ‘1 respected her decisions’ (3) ‘Be mindful, your goals and wishes are different’ (6) ‘We are really passionate about this. . . you have just got to try’ (3) ‘I am lucky to be able to do that’ (7) Phase 1 Qualitative Written and interview data (Informant number) Table 1 A comparison of data set examples from the phases of study used to explore, then test and complement the concepts of successful advocacy ‘Comprehensive assessment. . .and establishment of goals’ ‘Excellent team communication’ ‘Effective communication skills’ ‘Organising advanced care planning’ ‘Referrals to palliative care for specialist support if required’ ‘. . .the right to have. . .control over their lives. . .’ ‘. . .clients fully in control of how they wish their life to end’ ‘Provide on call support’ ‘. . .staying overtime to support family’ ‘. . .more proactive in engaging people’ ‘. . .advocating for adequate resources’ ‘Advocating for policy that supports. . . rights’ ‘Giving emotional support’ ‘Strong empathy’ ‘. . .understanding feelings’ ‘Thinking around/outside the square’ ‘Reflection and clinical review’ ‘Self-care’ ‘Experience’ ‘Any education’ ‘Colleagues’ ‘GP’s, Pall care’ ‘Life experience’ ‘Policies’, documentation/care plans, brochures’ ‘. . .trying’ ‘This involves giving of oneself and not just. . . clinical care’ ‘Strong desire to help’ ‘. . .close involvement’ ‘Commitment to providing quality’ ‘Knowing when. . .’ ‘Local knowledge’ ‘Intuition and knowing the client and family’ ‘Knowing yourself understanding. . .circumstances’ ‘Respect. . . recognition of individuality’ ‘. . .show them respect’ Answers to the open-ended questions 750 F. M. Reed et al. © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science A practice model for successful advocacy resources, conflicting values and misunderstanding of the DN role can increase the emotional reactions arising in EoL care and limit advocacy (16, 21). Emotional burden, under- and overinvolvement and moral conflict in rural professional and personal relationships are risks to successful person-centred advocacy care that DNs can manage using moral agency (20, 21). As a moral agent DNs can respond constructively to emotions, ethical dilemmas and misperceptions that limit EoL choice by thinking ‘outside the square’ and ‘looking at things from the other side’ (16, 19–21) (Table 1). The moral response to the EoL vulnerability of people can result in DNs going beyond the expectations; some people have of their role to improve access to choice and overcome the limits of the rural service resources provided (10, 21). Respectful person-centred EoL care for people in the rural home setting requires development of the ability of ‘judging’ one’s own actions in use of personal therapeutic resources to advocate successfully (Table 1). The nurse as an advocate DN advocates are mindful of the EoL vulnerability people may experience and respond with emotionally intelligent reflection and morally responsible action. As advocates, DNs react habitually out of respect with advocacy embedded in actions of holistic assessment, communication, organising resources, empowering and supporting people in the end stages of life to promote access to care choices (21). Access to person-centred EoL choice. DN advocates increase access to resources that promote person-centred EoL choice for rural Australians. Advocacy care from DNs extends to the self, the person, the family, colleagues, other healthcare workers and the community. Working together, ‘engaging people’, ‘advocating for policy’ and ‘adequate resources’ with a shared understanding of the values important to the person and the family can increase access to personalised care and goal planning (20, 21) (Table 1). DNs advocate for person-centred care uses holistic assessment at the individual level to gain an understanding of the person and family member’s resources, needs and values to be able to establish and achieve their goals. The relational process of sensitive ‘asking’, listening, observing and the ‘establishment of goals’ is used in an ongoing manner to assess the health and well-being of people involved in the evolving EoL home care situation (21) (Table 1). Ongoing holistic assessment informs DNs about care that is working well, the advocacy required and the resources people have to achieve their goals as care needs change (21, 33, 34). ‘Effective communication’ is used by DNs to help people manage fears, make plans, learn ways of giving and © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science 751 receiving care and express goals for living, dying and grieving (21) (Table 1). Advocacy amongst the care team is actioned by communicating the person’s self-determined EoL goals in a respectful way to everyone involved in caregiving (20, 21, 35). At organisational and community levels, DNs communicate the need for health service policy, resources and rural relationships that increase access to care and the quality of life for people in the rural community (16, 21, 35). Organising resources for care in a way that assists people in their self-determined goals is actioned as a result of assessment and communication. Equipping care in the home setting, ‘planning’, liaising with, and coordinating the varied care and referrals to ‘specialist support’ that can help people in rural areas requires advocacy in a timely response to empower their goals (16, 21) (Table 1). Empowering people with self-determination at times when their rights and respect for their values are threatened is the goal of advocacy care (16, 21). DN advocates empower people to ‘have control over their lives’ and greater choice at the levels of the individual and support network of family, informal and formal caregivers by working to strengthen understanding and ability in both the giving and receiving of person-centred EoL care (Table 1). Support for people to self-determine and achieve their EoL goals, and for their family and rural community to provide assistance, requires compassion for varied needs. DN relationships support differing levels of emotional, spiritual, physical, psychological, social and environmental needs with EoL advocacy care for, and about people (21, 34, 35). This support fortifies people who are vulnerable in the EoL for making difficult choices (16). Support can be promoted at the organisational level by DNs advocating for time and resources to develop person-centred rural relationships and reduce the need for additional effort, such as ‘staying overtime to support family’ (Table 1). Successful nurse advocacy results from the way rights, and values are respected and person-centred goals for care are used to direct limited resources and support the rural community (21). The development of self for therapeutic nurse advocacy enables a way of ‘really caring’ for and about people that can deliver successful outcomes and promote satisfaction in giving and receiving care (21, p. 10). Positive outcomes and emotions resulting from advocacy care feedback to reinforce the skill development of DNs with deep personal understanding and respect for the people and the situation (21, 32, 35): ‘It’s so good when it works’ (Informant 3, Phase 1). Implications for nursing The model represents theory developed from the study of how DNs advocate successfully for the goals of rural Australians using a philosophy of care. This way of caring is founded on respect for people, works through the 752 F. M. Reed et al. development of person-centred relationships and aims to empower the self-determination of people and achievement of their EoL goals. These basic principles found to be important to advocacy care in the study align the model with the seminal nursing literature of Curtin (31) Gadow (27, 28) Kohnke (20) and Benner (19, 35), focusing on a philosophy of nursing advocacy using respectful relationships to promote self-determination and communication. The model supports and expands existing nursing theory by revealing the process that leads DN advocacy from the foundation of respect to care satisfaction using a complex combination of concepts that incorporate theory of how emotions affect success. The model can inform rural services in the development of successful EoL advocacy with respectful person-centred care, specialised knowledge, reflective practice and supportive management and teams. Respectful nursing care. The model shows respect for the rights and values of others can foster an emotional awareness of the social influence on personal goals affecting care. Without the basis of respect that is learned and relearned throughout life and in relationships, the personal self-interests of the nurse or the authority of medicine can dominate care (27, 32). Advocacy care that respects and empowers the rights and values of people in the EoL is learned, supported and reinforced with successful outcomes that are satisfying for people both giving and receiving care. This theory contributes to the limited exploration of how nursing advocacy is developed and promoted by experience, education and positive role models that foster respectful, satisfying care and increase DN confidence for advocacy in adverse circumstances (19, 36, 37). The employment and retention of nurses possessing this respect as a foundation for successful advocacy is recommended in recognition of the difficulty in providing positive role models and collegial support for DNs who work as autonomous sole practitioners in rural EoL care situations. Specialised knowledge. The model highlights the importance of the specialised contextual knowledge that results from personal and professional relationships with rural people. The holistic understanding used to inform effective care provision reflects previous findings in the rural DN literature (10, 11). The personal, aesthetic, ethical and scientific ways of knowing for nursing care (38) are enlightened by the fuller understanding of the people in their rural homes and community situations. The ways of knowing offer DNs insight that informs person-centred advocacy care. The confidence of nurses in delivering advocacy has previously been found to increase with the knowledge gained from experience and education (19, 36). Factoring in time in DN service planning for a broad range of EoL and advocacy education and experience, and the development of collegial rural community resources is recommended to increase the understanding of person-centred advocacy in the home. Access and support for the use of care planning tools and information technology can promote self-advocacy and reduce the time and effort involved in travel for education that would alternatively be required (10, 21). Reflective practice. Relational care relies on the self-understanding of personal knowing represented in the model. The need to inform, understand and support the self to advocate for others is also evident in the advocacy literature (19, 20). Reflection on practice can be used by DNs to reorient their care and develop the habit of personcentred advocacy (21). The model is recommended as a resource for individual reflection on practice that can be used by novice and experienced DNs to identify their developmental strengths and needs in becoming successful advocates for access, choice and the EoL goals of rural Australians. Nursing reflection can also be encouraged using supportive conversations about how to improve care for self and others (39). DNs who work as sole practitioners have limited time with colleagues to reflect on concerns they have about EoL care. The use of peer support in reflective practice with team members and clinical supervision was suggested during the study to facilitate successful advocacy (21). Clinical supervision to assist the analysis and resolution of emotional and ethical dilemmas has been recommended in previous rural nursing studies (10, 40). Incorporating these resources to support reflective practice in EoL care is recommended for advocacy success. Supportive management and teams. Support from management and other health professionals shown in the model can encourage DNs to increase self-reliance in advocacy for resolving conflict. The combination of supportive resources and knowledge increases the willingness of DNs to be involved with people and develop their ability to meet fears about dying and opposition to personcentred goals (21). The literature supports the need for courage when advocacy may seem difficult to action due to emotions and circumstances (41, 42), or conflict with the dominant cultural expectations affecting EoL care (43, 44). Interprofessional and nursing relationships require well-developed communication skills to increase collegial support and promote teamwork for the person-centred goals (21). Effective communication has previously been promoted to reduce role misunderstanding and the risk of professional conflict arising from advocacy (20). The misunderstanding of the care DNs provide found in the study to affect rural relationships and care access reflects © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science A practice model for successful advocacy earlier study findings (45, 46). Interdisciplinary communication can increase understanding of the potential for quality care enabled by DN relationships and planning. Promotion of early referral from other care providers for DN care is recommended. Managers attending interdisciplinary meetings can educate other workers about the holistic person-centred care of DNs that supports people at home. Advocacy development and action are reinforced when DNs feel they are supported in their role autonomy to respond to emotional motivation. Managerial support for the use of role autonomy has been found to positively influence emotional care by nurses (47). The emotions found to drive nursing advocacy in this study are linked with the motivation of nurses for helping behaviour (28, 29). However, the model shows a further connection between emotional motivation and supports that assist the management of emotions generated in EoL care to enable coping, reduce fears and understand individual values. Feeling supported to think about the emotional and social determinants of health that influence thoughts and actions promotes autonomous advocacy using emotionally intelligent moral agency (21, 32, 48). Emotional intelligence development for DN advocacy is supported by informal teamwork (30). This support from others has been found to help nurses develop advocacy expertise in critical care (19). In rural situations where collegial support is less available, the formal support of clinical supervision together with emotional intelligence education may facilitate the moral agency of DNs to manage the emotional stressors that influence EoL care (10, 21, 40). Moral guidance can reduce the risks inherent with using advocacy within a medically dominated healthcare system (20). These supports can be promoted by management to increase understanding and nursing role autonomy to act ‘freely’ using the moral agency of advocacy care (32, p. 2). This model way of caring shows EoL advocacy involves a person-centred philosophy rather than being used as a role when required. The possibility of DNs going beyond the realms of care expected by others to fulfil the moral responsibilities of this philosophy in an environment of restricted rural resources needs to be recognised and acknowledged. Feeling supported in morally motivated actions that take DNs to a higher level of perceived duty can reduce the risk of work dissatisfaction. The model shows a combination of DN advocacy resources that can be fortified with planning and support strategies. DNs and health services can support advocacy capacity in this specialised field of practice to improve the quality of rural EoL care. Ongoing research is recommended to inform the potential for the advocacy care philosophy to promote person-centred DN and funding that supports community and palliative care policy direction. © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science 753 Limitations The practice model is drawn from concepts derived and substantiated by the experience and reflection on the successful advocacy of rural DNs and comparison with existing theory. Testing the model in practice to gain the perspective of others involved in giving and receiving care can further inform the suitability of the model to guide DN EoL care in rural Australia. Testing for broader use could extend the value and application of the advocacy care model to other fields of practice. Conclusion The study gave voice to rural Australian DNs to identify the process of successful person-centred EoL advocacy care and develop a model for practice. The model represents new theory for DN practice supported by existing concepts found in the nursing advocacy literature. Successful advocacy care based on respect and enabled by willing, knowing and supported rural DNs with emotional intelligence promotes their action as moral agents for access to advocacy assessment, communication, organisation, empowerment and the support of people for successful EoL goals. The satisfaction derived from this way of caring for people motivates further effort to strengthen and empower rural communities to care, live, grieve and die as well as possible. The model can guide health service by understanding how rural DNs successfully use their specialised generalist role to advocate for person-centred goals in a way that meets healthcare policy objectives. This may result in improved EoL experiences as the needs of an ageing rural population increase, and new nurses enter the field of home care. Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to the rural nurses who contributed to this study. Conflict of interest The authors declare there is no conflict of interests. Author contribution Frances M. Reed is the primary author of the manuscript, responsible for conducting the research and literature reviews, conceptualising the first draft and subsequent editing. Les Fitzgerald and Melanie R. Bish have contributed by supervising the process, team discussions of the model and reviewing and suggesting edits for drafts of the manuscript. 754 F. M. Reed et al. Ethical approval La Trobe University FHEC14/037. References 1 World Health Organisation. Palliative Care for Older People: Better Practices. 2011, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Denmark, http://www.who.int/cance r/palliative/definition/en/ (last accessed 2 January 2017). 2 World Health Organisation. (2011). Palliative care for older people: better practices. Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe. 3 Palliative Care Australia. Health system reform and care at the end of life: a guidance document. In Department of Health and Ageing, 2010. Palliative Care Australia, Deakin West. 4 Carers Australia. Dying at home: preferences and the role of unpaid carers: a discussion paper on supporting carers for in-home, end-of-life care. 2015, Australia, http://www.carersa ustralia.com.au/storage/Dying%20at %20home_Final2.pdf (last accessed 14 August 2016). 5 Khan SA, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. End-of-life care-what do cancer patients want? Natl Rev Clin Oncol 2014; 11: 100–8. 6 Agency for Clinical Innovation. Framework for the Statewide Model for Palliative and End of Life Care Service Provision. 2013, ACI Palliative Care Network, Chatswood. 7 Australian Government. Commonwealth Home Support Programme (CHSP) Guidelines Overview. 2015, Australian Government. https://dss. gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/06 _2015?chsp_programme_guidelines_-_ accessible_version.pdf (last accessed 12 Feb 2016). 8 National Rural Health Alliance. Australia’s health system needs re-balancing: a report on the shortage of primary care services in rural and remote areas. 2011, Deakin West, http://nrha.ruralhealth.org.au/sites/ default/files/documents/nrha-policydocument/position/pos-full-comple mentary-report-27-feb-11.pdf (last accessed 3 August 2016). 9 Wilkes LM, Beale B. Palliative care at home: stress for nurses in urban and rural New South Wales, 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Australia. Int J Nurs Pract 2001; 7: 306–13. Cumming M, Boreland F, Perkins D. Do rural primary health care nurses feel equipped for palliative care? Aust J Primary Health 2012; 18: 274–83. Victorian Department of Health. Hume region review of HACC district nursing services. 2012, Victorian Government, http://www.health.vic. gov.au/hacc/publications/downloads/ hume/dns_report2012.pdf. (last accessed 19 January 2016) Kemp A, Harris E, Comino E. Changes in community nursing in Australia: 1995–2000. J Adv Nurs 2005; 49: 307–14. T€ ornkvist L, Gardulf A, Lars-Erik Strender L-E. Patients’ satisfaction with the care given by district nurses at home and at primary health care centres. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 67–74. Reed FM, Fitzgerald L, Bish MR. District nurse advocacy for choice to live and die at home in rural Australia: a scoping study. Nursing Ethics 2015; 22(4): 479–492. International Council of Nurses. Describing the nursing profession: dynamic language for advocacy, 2007, http://www.icn.ch/images/sto ries/documents/publications/free_pub lications/describing_the_nursing_pro fession.pdf (last accessed 23 January 2016). Community Health Nursing Special Interest Group. The role and scope of community health nurses in Victoria, and their capacity to promote health and wellbeing: advocating for health. 2010, http://.www.anfvic.asn.au/sig s/topics/2298.html (last accessed 22 January 2016). Reed FM, Fitzgerald L, Bish MR. Mixing methodology, nursing theory and research design for a practice model of district nursing advocacy, Nurse Researcher 2016; 23(3): 37–41. Hall JN. Pragmatism, evidence, and mixed methods evaluation. New Dir Eval 2013; 138: 15–26. Benner PE, Tanner CA, Chesla CA. Expertise in Nursing Practice: Caring, 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Clinical Judgment and Ethics. 1996, Springer, New York. Kohnke M. Advocacy, Risk and Reality. 1982, C.V. Mosby Company, Missouri. Reed FM, Fitzgerald L, Bish MR. Rural district nursing experiences of successful advocacy for person-centered end-of-life choice. Journal of Holistic Nursing 2016; 35(2): 151–164. Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res 2001; 1: 385– 405. Davies KA, Lane AM, Devonport TJ, Scott JA. Validity and Reliability of a Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale (BEIS-10). J Ind Diff 2010; 31: 198– 208. Qualtrics. 2015, http://www.qualtric s.com (last accessed 1 January 2017) Copp LA. The nurse as advocate for vulnerable persons. J Adv Nurs 1986; 11: 255–63. Benner P. The roles of embodiment, emotion, and lifeworld for rationality and agency in nursing. Nurs Philos 2000; 1: 5–19. Gadow S. Caring for the dying: advocacy or paternalism. Death Educ 1979; 3: 387–98. Gadow S. Advocacy nursing and new meanings in aging. Nurs Clin North Am 1979; 14: 81–91. Travelbee J. What’s wrong with sympathy? Am J Nurs 1964; 64: 68–71. Davies S, Jenkins E, Mahhett G. Emotional intelligence: district nurses’ lived experiences. Br J Community Nurs 2005; 15: 141–6. Curtin L. The nurse as advocate: a philosophical foundation for nursing. Adv Nurs Sci 1979; 1: 1–10. Robley LR. Being Moral Agents: The Experiences of Nurses Considered to Be Experts in the Care of Dying Patients. 1998, Georgia State University, Thesis. Ezeonwu MC. Advocacy: a concept analysis. Community Health Nurs 2015; 32: 115–28. Godkin JL. Making a Difference: A Study of Patient Advocacy Among Expert Dialysis Nurses. 2006, The University of © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science A practice model for successful advocacy 35 36 37 38 Texas Medical Branch Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Thesis. Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. 1984, Addison-Wesely Publishing Company: Nursing Division, Merlo Park, CA. Seal M. Patient advocacy and advance care planning in the acute hospital setting. Aust J Adv Nurs 2007; 24: 29–36. Thacker KS. Nurses’ advocacy behaviors in end-of-life nursing care. Nurs Ethics 2008; 15: 174–85. Carper BA. Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. In Philosophical and Theoretical Perspectives for Advanced Nursing Practice, 4th edn (Cody WK ed), 2006, Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury MA, 19–27. © 2017 Nordic College of Caring Science 39 Street A. Nursing Replay: Researching Nursing Culture Together. 1995, Chuchill Livingstone, South Melbourne. 40 Rose J, Glass N. An Australian investigation of emotional work, emotional well-being and professional practice: an emancipatory inquiry. J Clin Nurs 2010; 19: 1405–14. 41 Karlsson C, Berggren I. Dignified end-of-life care in the patients’ own homes. Nurs Ethics 2011; 18: 374– 85. € 42 Ohman M, S€ oderberg S. District nurses - sharing an understanding by being present. Experiences of encounters with people with serious chronic illness and their close relatives in their homes. J Clin Nurs 2004; 13: 858–66. 43 Kerfoot K. Courage, leadership, and end-of-life care: when courage counts. Medsurg Nurs 2012; 21: 319–20. 755 44 Swerissen H, Duckett S. Dying Well. 2014, Grattan Institute, Australia. 45 Annells M, DeRoche M, Koch T, Lewin G, Locke J. District Nursing Research Priorities According to a Panel of District Nurses in Australia. 2003, La Trobe University, St Kilda. Contract No.: ISBN 1 9200868 00 3. 46 Miles GM. The Nature of District Nursing in Victoria: Thesis. 2007, University, La Trobe. 47 Pisaniello SL, Winefield HR, Delfabbro PH. The influence of emotional labour and emotional work on the occupational health and wellbeing of South Australian hospital nurses. J Vocat Behav 2012; 80: 579–91. 48 Lindahl B, Sandman P. The role of advocacy in critical care nursing: a caring response to another. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1998; 14: 179–86. Copyright of Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.