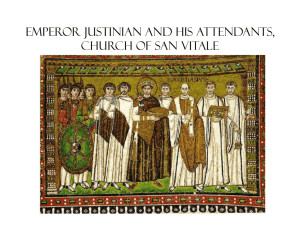

CHRC Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) i-ii www.brill.nl/chrc Contents Jan N. Bremmer, Iconoclast, Iconoclastic, and Iconoclasm: Notes Towards a Genealogy ............................................................ Rob van de Schoor, “Ignatio atque immo Deo volente”: Canisius’s Tertia probatio in Rome and His Mission to Sicily .......................... Herman Paul and Bart Wallet, A Sun that Lost its Shine: The Reformation in Dutch Protestant Memory Culture, 1817-1917 ....................................................................... 1 19 35 REVIEW SECTION Anneke B. Mulder-Bakker and Jocelyn Wogan-Browne (Eds.), Household, Women, and Christianities in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages [Medieval women: texts and contexts 14] Mathilde van Dijk .......................................................................... Ineke van ’t Spijker, Fictions of the Inner Life. Religious Literature and Formation of the Self in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries [Disputatio 4] Willemien Otten ............................................................................ Victor Beyer, Les vitraux de l’ancienne église des Dominicains de Strasbourg [Corpus Vitrearum France IX 2] Édith Weber ................................................................................... Mercedes Rubio, Aquinas and Maimonides on the Possibility of the Knowledge of God. An Examination of the Quaestio de Attributis [Amsterdam Studies in Jewish Thought 11] Pim Valkenberg .............................................................................. Alastair Hamilton, The Copts and the West, 1439-1822: The European Discovery of the Egyptian Church [Oxford — Warburg Studies] Johannes den Heijer ....................................................................... Michael Tavuzzi, Renaissance Inquisitors: Dominican Inquisitors and Inquisitorial Districts in Northern Italy, 1474-1527 [Studies in the History of Christian Traditions 134] Alastair Hamilton ........................................................................... © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2008 65 68 70 72 74 79 ii Contents / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) i-ii La Réforme en France et en Italie: Contacts, comparaisons et contrastes. Études réunies par Philip Benedict, Silvana Menchi et Alain Tallon [Collection de l’École française de Rome 384] Alastair Hamilton ........................................................................... 81 Hermann von Kerssenbrock, Narrative of the Anabaptist Madness: The Overthrow of Münster, the Famous Metropolis of Westphalia Alastair Hamilton ........................................................................... 83 Jean Sturm, « De literarum ludis recte aperiendis liber » (De la bonne manière d’ouvrir des écoles de Lettres) Édith Weber ................................................................................... 85 R. Ward Holder, John Calvin and the Grounding of Interpretation: Calvin’s First Commentaries [Studies in the History of Christian Traditions 127] Raymond A. Blacketer .................................................................... 87 Robin A. Leaver, Luther’s Liturgical Music. Principles and implications [Lutheran Quarterly Books] Ulrike Hascher-Burger ................................................................... 89 Michael S. Springer, Restoring Christ’s Church: John a Lasco and the Forma ac ratio [St Andrews Studies in Reformation History] Alastair Hamilton ........................................................................... 91 Matthias Pohlig, Zwischen Gelehrsamkeit und konfessioneller Identitätsstiftung. Lutherische Kirchen- und Universalgeschichtsschreibung 1546-1617 [Spätmittelalter und Reformation, Neue Reihe 37] Kai Bremer ......................................................................................... 93 Peter Marshall, Mother Leakey & the Bishop: A Ghost Story. Craig Harline ................................................................................. 96 Tanya Kevorkian, Baroque Piety: Religion, Society, and Music in Leipzig, 1650-1750 Édith Weber ................................................................................... 98 J. Vree, Kuyper in de kiem. De precalvinistische periode van Abraham Kuyper 1848-1874 Albert de Lange .............................................................................. 102 Lawrence M. Yoder, The Muria Story: A History of the Chinese Mennonite Churches of Indonesia Chris de Jong ................................................................................. 105 Corwin Smidt, Donald Luidens, James Penning and Roger Nemeth, Divided by a Common Heritage: The Christian Reformed Church and the Reformed Church in America at the Beginning of a New Millennium [The Historical Series of the Reformed Church in America 54] Hans Krabbendam ......................................................................... 107 Books Received .................................................................................. 109 CHRC Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 www.brill.nl/chrc Iconoclast, Iconoclastic, and Iconoclasm: Notes Towards a Genealogy Jan N. Bremmer Abstract This article aims to contribute to a better understanding of the genealogy of the terms ‘iconoclast(ic)’ and ‘iconoclasm.’ After some observations on the beginning of early Christian art that stress the necessity of abandoning a monolithic view of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic art regarding their iconic/aniconic aspects, it is noted that ‘iconoclast’ is mentioned first just before the start of the iconoclastic struggle and always remained rare in Byzantium. It became known in the West by Anastasius’s Latin translation of Theophanes’ Chronographia Tripartita. From there it was probably picked up by Thomas Netter, whose Doctrinale against Wycliffe and his followers proved to be very influential in the early times of the Reformation when images were a focus of intense debate between Catholics and Protestants. Thus the term gradually gained in popularity and also gave rise to ‘iconoclasm’ and ‘iconoclastic.’ The present popularity of the term has promoted the grouping together of events that probably should not be considered together. It has also made scholars focus on Protestant vandalism during the Reformation period rather than on the much greater damage to medieval art caused by the Catholic Baroque period. Keywords Iconoclasm, iconoclast(ic), iconoclastic period, early Christian art, Reformation and art, Baroque art. Although in recent decades we have had some excellent books on iconoclasm and iconoclasts,1 these do not satisfactorily discuss the question as to when, where and why the terms ‘iconoclast’ and ‘iconoclasm’ originated. In fact, as the German historian Norbert Schnitzler more recently observed: “Wenig ist bislang über die Geschichte des Ikonoklasmus-Begriffs beziehungsweise über die volkssprachlichen Synonyme ‘Bildersturm,’ ‘Bilderstürmer’ bekannt.”2 It is 1 The literature on the subject is immense and I limit myself to the more recent studies: D. Freedberg, Iconoclasts and their motives (Maarssen, 1985); A. Demandt, Vandalismus: Gewalt gegen Kultur (Berlin, 1997); D. Gamboni, The Destruction of Art (London, 1997); see also Gamboni, ‘Preservation and destruction, oblivion and memory,’ in Negating the Image, ed. A. McClanan and J. Johnson (Aldershot, 2005), pp. 163-74. 2 N. Schnitzler, Ikonoklasmus–Bildersturm. Theologischer Bilderstreit und ikonoklastisches Handeln während des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts (Munich, 1996), p. 21. © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2008 DOI: 10.1163/187124108X316413 2 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 the aim of this paper to make a small contribution to that answer, even if it is limited to ‘iconoclast,’ ‘iconoclastic,’ and ‘iconoclasm’; in addition, I would also like to make a few observations as to how these terms may have influenced our views of certain periods and events. Naturally, one would expect the terms ‘iconoclasm’ and ‘iconoclast’ to appear first at the time of the famous iconoclastic struggle in Byzantium, as is said for example by Gamboni, who notes that the term ‘iconoclast’ was “used first in Greek in connection with the Byzantine ‘Quarrel of the Images,’ ”3 but this is only partially true. Before we demonstrate this, it might be useful to start with a few observations on the pre-history of the terms and the Byzantine events, as more recent studies enable us to paint a more exact and nuanced picture than was previously possible.4 Let us start with a very simple question, albeit one that I do not find asked in the recent literature. Why did the Christians call the image an ‘icon’? The term may seem an obvious one for an outsider, but the ancient Greeks had a very varied vocabulary for images and statues, such as agalma, andrias, bretas, eidôlon, eikôn, hedos, hidruma, kolossos, and xoanon.5 Of these terms, bretas was traditionally used only in poetry, xoanon referred to the wood of which a statue was made, and andrias, hedos, and kolossos referred to particular kinds of statues. That is probably why only three terms remained current in the vocabulary of the early Christians: eidôlon, agalma, and eikôn. The first one, which has given us the term ‘idolatry’ via early Christianity, carried the overtone of 3 Gamboni, Destruction, 18. Good introductions are A. Bryer and J. Herrin, eds., Iconoclasm (Birmingham, 1977); A. Grabar, L’iconoclasme byzantin: le dossier archéologique, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1984); P. Schreiner, ‘Der byzantinische Bilderstreit: kritische Analyse der zeitgenössischen Meinungen und das Urteil der Nachwelt bis heute,’ in Bisanzio, Roma e l’Italia nell’ Alto Medioevo, 2 vols. (Spoleto, 1988), 2: 319-407. Very helpful recent studies for the period leading up to and including the iconoclastic period are H.G. Thümmel, Bilderlehre und Bilderstreit: Arbeiten zur Auseinandersetzung über die Ikone und ihre Begründung vornehmlich im 8. und 9. Jahrhundert (Würzburg, 1991); idem, Die Frühgeschichte der ostkirchlichen Bilderlehre (Berlin, 1992), and idem, Die Konzilien zur Bilderfrage im 8. und 9. Jahrhundert: das 7. Ökumenische Konzil in Nikaia 787 (Paderborn, 2005); R. Cormack, Byzantine Art (London, 2000), pp. 75-102; L. Brubaker and J. Haldon, Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era (ca. 680-850): The Sources: An Annotated Survey (Aldershot, 2001). Still inspiring: P. Brown, Society and the Holy in Late Antiquity (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1982), pp. 251-301 (‘A Dark Age Crisis: Aspects of the Iconoclastic Controversy,’ 1st ed. 1973). 5 For these terms see A. Hermary, ‘Les noms de la statue chez Hérodote,’ in Eukrata: mélanges offerts à Claude Vatin, ed. M.-C. Amouretti and P. Villard (Aix-en-Provence, 1994), pp. 21-9 (agalma, andrias, eikôn, kolossos); M. Dickie, ‘What is a Kolossos and how were Kolossoi Made in the Hellenistic Period?,’ Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 37 (1996), 237-57; T. Scheer, Die Gottheit und ihr Bild (Munich, 2000), pp. 8-18 (agalma), 19-21 (xoanon), 21-3 (hedos), and 24-33 (bretas). The bibliography in Thümmel, Frühgeschichte (see above, n. 4), pp. 23-4, is completely out of date. 4 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 3 ‘phantom,’ ‘unreal,’ and its use was preferred to indicate the fact that the pagan gods were nothing more than human imaginations and phantasies.6 Agalma was mostly used by the Greeks and Romans for the statues of their own gods, whereas eikôn was mainly employed for statues and images of mortals, from the living emperor to a local official.7 Eikôn, then, was the least offensive and, I suggest, therefore preferred by the Christians to indicate paintings, reliefs, and statues; it also had the advantage that it suggested a greater distance to the original and thus could be better used to indicate the “image of God,” as in the story of the Creation where God created man “according to our eikôn and likeness” (Genesis 1,26).8 It is well known that the early Christians were opposed to the cult of images.9 Yet the degree and the location of this opposition are much harder to pinpoint than is often realised, and a satisfactory synthesis of the archaeological evidence and the literary tradition has not yet been achieved.10 Four points merit particular attention. First, we should avoid the simplistic distinction between the rational intellectuals on the one side and the credulous statue-venerating people on the other.11 Second, our early literary evidence derives from Christian apologists who naturally railed against the images and their veneration, as pagan ‘idols’ still were important and may have exerted a pull on some Christians, even though contemporary pagan authors carefully distinguish between 6 J.C.M. van Winden, ‘Idolum and Idololatria in Tertullian,’ Vigiliae Christianae 36 (1982), 108-14; S. Saïd, ‘Deux noms de l’image en grec ancien: idole et icône,’ Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 1987, pp. 309-30, there pp. 311-19. 7 The difference between agalma and eikôn, which is not always clear, was established by L. Robert, Opera Minora Selecta: épigraphie et antiquités grecques, 7 vols. (Amsterdam, 1968-90), 2: 832-40; see also S. Price, Rituals and Power (Cambridge, 1984), pp. 176-9; K. Koonce, ‘ Άγάλμα and εἰκών,’ The American Journal of Philology 109 (1988), 108-10. For eikôn, see Saïd, ‘Deux noms de l’image’ (see above, n. 6), 319-30. 8 Still useful on the image of God: G. Ladner, ‘The concept of the image in the Greek Fathers and the Byzantine Iconoclastic Controversy,’ Dumbarton Oaks Papers 7 (1953), 3-34. 9 For an excellent survey of the literature see H. Feld, Der Ikonoklasmus des Westens (Leiden, 1990), pp. 2-6; add J. Kollwitz, ‘Zur Frühgeschichte der Bilderverehrung,’ in W. Schöne et al., Das Gottesbild im Abendland (Witten and Berlin, 1957), pp. 57-76. 10 For the first two centuries, a good start is Ch. Murray, ‘Art and the Early Church,’ Journal of Theological Studies, NS 28 (1977), 215-57 and idem, Rebirth and Afterlife. A study of the transmutation of some pagan imagery in early Christian funerary art (Oxford, 1981); P.C. Finney, The Invisible God: the earliest Christians on art (Oxford, 1994), to be read with the reviews by W. Wischmeyer, International Journal of the Classical Tradition 3 (1997), 339-48; L. Rutgers, Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 40 (1997), 245-9; and N. Zeegers, Revue d’Histoire Ecclésiastique 93 (1998), 481-6. Without notes but very balanced, L. Rutgers, Subterranean Rome. In Search of the Roots of Christianity in the Catacombs of the Eternal City (Louvain, 2000), pp. 82-117. 11 See now the convincing refutation of this influential thesis of Th. Klauser (1894-1984), by Finney, The Invisible God (see above, n. 10), pp. 9-10. 4 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 the gods and their images.12 Third, the Christians lived in a world full of images from which it would have been very hard to extract themselves; and indeed, figurative art by Christians is already attested around 200, when in Carthage the glass chalice of the Eucharist was ornamented with a picture of God/Christ as the Good Shepherd.13 Fourth and finally, Jaś Elsner has recently warned against the use/validity of the expressions “Jewish art” and “Christian art.”14 Rightly so, as the first period of “Christian art” consisted of the selection of certain pagan themes; Christian art proper only gradually arises after the conversion of the Roman Empire.15 It is not surprising, then, that both literary and material evidence indicate that many early Christians did not object to representational and figurative art: it is only God Himself who was apparently never represented. What we have to discard, therefore, is the monolithic picture of an iconophobic Christianity that gradually became replaced by an iconophilic Church. There were various ideas and practices in circulation, as we can also note among the Jews, where we find this combination of dogmatic rejection and practical acceptance of figurative art too, but with a different limit to the representation: the Jews not only did not represent Yahweh but they also did not illuminate the Torah,16 whereas Biblical manuscripts became illuminated from the beginning of the fifth century onwards.17 The Jews were not unique in this respect in the ancient world. Among the Nabataeans we can also find both the aniconic and the iconic tradition;18 in fact, even in Mecca there is clear proof of representations in the Kaaba before Muhamed.19 It is important to note this 12 V. Fazzo, La giustificazione delle imagini religiose: I, La tarda antichità (Naples, 1977). Tertullian, De pudicitia 7.1, 10.12: pastor, quem in calice depingis, cf. V. Buchheit, ‘Tertullian und die Anfänge der christlichen Kunst,’ Römische Quartalschrift 69 (1974), 133-42. 14 J. Elsner, ‘Archaeologies and agendas: reflections on late ancient Jewish art and early Christian art,’ The Journal of Roman Studies 93 (2003), 114-28. 15 For good surveys see F.W. Deichmann, Archeologia cristiana (Rome, 1993); W. Kemp, Christliche Kunst: ihre Anfänge, ihre Strukturen (Munich, 1994). 16 For Jewish art and iconoclasm see now S. Fine, Art & Judaism in the Greco-Roman World (Cambridge, 2005); add R. Schick, The Christian Communities of Palestine from Byzantine to Islamic rule (Princeton, 1995), pp. 202-4 (Jewish iconoclasm); O. Keel, ‘Warum im Jerusalemer Tempel kein anthropomorphes Kultbild gestanden haben dürfte,’ in Homo Pictor, ed. G. Boehm (Munich and Leipzig, 2001), pp. 244-82; G. Koch, ‘Jüdische Sarkophage der Kaiserzeit und der Spätantike,’ in What Athens has to do with Jerusalem, ed. L. Rutgers (Louvain, 2002), pp. 189-210. 17 See now J. Lowden, ‘The Beginnings of Biblical Illustration,’ in Imaging the Early Medieval Bible, ed. J. Williams (University Park, PA, 1999), pp. 9-59. 18 J. Basile, ‘Two Visual Languages at Petra: Aniconic and Representational Sculpture of the Great Temple,’ Near Eastern Archeology 65 (2002), 255-8. 19 For the pre-Muhamed period see M. Lecker, ‘Idol Worship in Pre-Islamic Medina (Yathrib),’ Le Muséon 106 (1993), 331-46; G.R. Hawting, The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam (Cambridge, 1999); G. King, ‘The Sculptures of the Pre-Islamic Haram at Makka,’ in Cairo to 13 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 5 variety of views, as even Hans Belting in his latest book rather simplistically speaks of the “Glaubenswelt der Juden und Araber mit ihrer an-ikonischen Kultur.”20 The situation gradually changed after Constantine. Before his conversion,21 the Christians could hardly build churches, let alone decorate them.22 However, even though Constantine himself probably never went to church and instead promoted the veneration of relics,23 the Christians started to fill their newly built churches with statues, mosaics, and paintings on the walls. It is probably therefore not by chance that Bishop Eusebius argues against a request of Constantine’s half-sister Constantia, who sympathised with the Arians,24 for an image (eikôn) of Christ,25 perhaps the first sign of the later well attested devotion of women to icons.26 And it would take nearly a century before we start to hear of objections to the images displayed in the churches: Epiphanius Kabul: Afghan and Islamic Studies Presented to Ralph Pinder-Wilson, ed. W. Ball (Melisende, 2002), pp. 144-50. For the Islamic ‘Bilderverbot’ see R. Paret, Schriften zum Islam (Stuttgart, 1981), pp. 213-69; D. van Reenen, ‘The Bilderverbot, a new survey,’ Der Islam 67 (1990), 27-77. 20 H. Belting, Das echte Bild (Munich, 2005), p. 145. 21 On Constantine’s conversion see now Bremmer, ‘The Vision of Constantine,’ in Land of Dreams. Festschrift Ton Kessels, ed. A. Lardinois and M. van de Poel (Leiden, 2006), pp. 57-79 (with extensive bibliography). 22 For recent surveys see G. Snyder, Ante pacem: archaeological evidence of church life before Constantine (Macon, 1985); L.M. White, The Social Origins of Christian Architecture, 2 vols. (Valley Forge, PA, 1997), 2: 121-258. 23 R. Grigg, ‘Constantine the Great and the Cult without Images,’ Viator 8 (1977), 1-32; N. Mclynn, ‘The Transformation of Imperial Churchgoing in the Fourth Century,’ in Approaching Late Antiquity, ed. S. Swain and M. Edwards (Oxford, 2004), pp. 253-70. 24 Note that during the Iconoclastic Controversy the Iconophiles assocated the Arians with the Iconoclasts: D. Gwynn, ‘From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Construction of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy,’ Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 47 (2007), 225-51. This has been overlooked by M. Wiles, Archetypal Heresy: Arianism through the Centuries (Oxford, 1996), p. 53. Add also to his literature about the Cathars (ibidem): G. Rottenwöhrer, Der Katharismus, 4 vols. (Bad Honnef, 1982-93), 3: 440-51 and, with a new etymology of ‘Cathars,’ Bremmer, The Rise and Fall of the Afterlife (New York and London, 2002), p. 68. 25 S. Gero, ‘The True Image of Christ: Eusebius’ Letter to Constantia Reconsidered,’ Journal of Theological Studies, NS 32 (1981), 460-70; H.G. Thümmel, ‘Eusebios’ Brief an Kaiserin Konstantia,’ Klio 86 (1984), 210-22. For the text see now Thümmel, Frühgeschichte (see above, n. 4), pp. 282-4; A. von Stockhausen, ‘Einige Anmerkungen zur Epistula ad Constantiam des Euseb von Cäsarea,’ in T. Krannich et al., Die ikonoklastische Synode von Hiereia 754 (Tübingen, 2002), pp. 92-112 (with translation). 26 J. Herrin, ‘Women and the Faith in Icons in Early Christianity,’ in Culture, Ideology and Politics, ed. R. Samuel and G. Stedman Jones (London, 1982), pp. 56-83; A.-M. Talbot and A. Kazhdan, ‘Women and Iconoclasm,’ Byzantinische Zeitschrift 84/85 (1991/1992), 391-408, reprinted in A.-M. Talbot, Women and Religious Life in Byzantium (Aldershot, 2001), Ch. III; P. Hatlie, ‘Women of Discipline During the Second Iconoclast Age,’ Byzantinische Zeitschrift 89 (1996), 37-44; R. Cormack, ‘Women and Icons, and Women in Icons,’ in Women, Men and Eunuchs, ed. L. James (London and New York, 1997), pp. 24-51. 6 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 (ca. 310-403), bishop of Salamis on Cyprus, destroyed an image for religious reasons at the end of the fourth century; in other words, at least some iconoclasts were already around at that time.27 Unfortunately, the prehistory of the icon is still unclear and its origin, whether out of the imperial image or out of pagan panels, is a subject of current debate. Most recently, Thomas Mathews has made a forceful case for the latter against earlier views, although he did not pay enough attention to another possible origin.28 Admittedly, he mentions the scene with the worship of a portrait (eikôn) of the Apostle John in the Apocryphal Acts of John, which was probably written in southwestern Asia Minor about AD 150,29 but it has escaped him that Irenaeus, a younger contemporary of AJ ’s author, informs us that Carpocratian gnostics wreathed and worshipped portraits of Jesus, Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, and other philosophers, whereas the gnostic Simonians worshipped Simon and Helen.30 And Augustine mentions that a certain Marcella, a Carpocratian, not only worshipped Homer, Pythagoras, and Jesus but also burned incense in front of their images,31 a practice undoubtedly going back to the Epicureans, who had started to worship paintings and other representations of their master Epicurus.32 The evidence we have points 27 See his ‘Letter to John of Jerusalem’ in PG 43.390; cf. the still important study of K. Holl, Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kirchengeschichte, 3 vols. (Tübingen, 1928-32), 2: 351-87 (1st ed. 1916); H.G. Thümmel, ‘Die bilderfeindlichen Schriften des Ephiphanios von Salamis,’ Byzantinoslavica 47 (1986), 169-88; P. Marival, ‘Épiphane, “docteur des iconoclastes”,’ in Nicée II, 7871987, ed. F. Boespflug and N. Lossky (Paris, 1987), pp. 51-62; P. Speck, ‘Die Bilderschriften angeblich des Epiphanios von Salamis,’ in Varia II = Poikila Byzantina 6, ed. A. Berger et al. (Bonn, 1987), pp. 312-5. 28 T.F. Mathews, ‘The Emperor and the Icon,’ Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia 15 (N.S. 1) (2001), 163-78, to be read with the critique by S. Sande, ‘Pagan Pinakes and Christian Icons. Continuity or Parallelism?,’ Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia 18 (N.S. 4) (2004), 81-100; T.F. Matthews, The Clash of Gods, 2nd ed. (Princeton, 1999), pp. 177-90, to be read with the review of J. Deckers, Byzantinische Zeitschrift 94 (2001), 736-41, and Matthews’s more balanced ‘Early Icons of the Holy Monastery of Saint Catharine at Sinai,’ in Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai, ed. R. Nelson and K. Collins (Los Angeles, 2006), pp. 39-55. 29 J.N. Bremmer, ‘The Apocryphal Acts: Authors, Place, Time and Readership,’ in The Apocryphal Acts of Thomas, ed. J.N. Bremmer (Louvain, 2001), pp. 149-70, there p. 153 (date) and p. 158 (place). 30 Irenaeus, Adversus haereses 1.23.4, 1.25.6, used by Epiphanius, Adv. haer. 27.6; the worship of Simon’s portrait is also mentioned by Eusebius in his letter to Constantia (see above, n. 25); S. Settis, ‘Severo Alessandro e i suoi Lari (S.H.A., S.A., 29, 2-3),’ Athenaeum 50 (1972), 237-51; J.D. Breckenridge, ‘Apocrypha of Early Christian Portraiture,’ Byzantinische Zeitschrift 67 (1974), 101-9. 31 Augustine, De haer. 7. 32 Cicero, De finibus 5.1.3, cf. B. Frischer, The Sculpted Word (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London, 1982), pp. 81-96. J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 7 to a localisation of the practice especially among the non-orthodox Christians, Gnostics and Arians, and this is confirmed by the fact that the Manicheans carried a painting of Mani in processions and that Mani himself “published” a book with paintings, called Eikôn.33 Mathews’s concentration on the origin of the icon from pagan panels also does not do justice to the whole complex of issues that have played a role in the origin and rise of the icon. We should take into account the problems of the acceptance of figurative art in general, the production and art historical development of, especially, the panel portrait,34 the rise of images of Christ,35 the survival of icons both in East and West,36 and the actual devotion to those images, which started to emerge as an important social phenomenon only in the time of Justinian and accelerated in the last decades of the seventh century.37 It is not surprising, then, that after the initial rise of the icon also the first, sometimes violent, objections are mentioned. We already hear of such iconoclastic events in Asia Minor before the outbreak of the iconoclastic struggle proper,38 although the more or less contemporary ones in Armenia, which are 33 Manichaeans: Eusebius’s letter to Constantia (see above, n. 25). Mani: H.-J. Klimkeit, Manichaean Art and Calligraphy (Leiden, 1982), pp. 15-20; S. Lieu, Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval Cina, 2nd ed. (Tübingen, 1992), pp. 175-7, 276; M. Heuser and H.-J. Klimkeit, Studies in Manichean Literature and Art (Leiden, 1998), pp. 271-5; C. Markschies, ‘Gnostische und andere Bilderbücher in der Antike,’ Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum 9 (2005), 100-21, there 117-20; W. Sundermann, ‘Was the Ārdhang Mani’s Picture-Book?,’ in Il Manicheismo: nuove prospettive della richerca, ed. A. van Tongerloo and L. Cirillo (Turnhout, 2005), pp. 373-84. 34 For evidence of painters in Egypt see now K. Worp, ‘Zu den ζωγράφοι in Ägypten’ and H. Harrauer and R. Pintaudi, ‘Abrechnung für den Maler Julianos,’ in Gedenkschrift Ulrike Horak (P. Horak), ed. H. Harrauer and R. Pintaudi, 2 vols. (Florence, 2004), 1: 43-6 and 10912, respectively. 35 E. von Dobschütz, Christusbilder (Leipzig, 1899); M. Büchsel, ‘Das Christusporträt am Scheideweg des Ikonoklastenstreits im 8. und 9. Jahrhundert’ Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft 25 (1998), 7-52; Belting, Das echte Bild (see above, n. 20), pp. 52-85. 36 For a list of the earliest icons see L. Langen, ‘La peinture d’icônes en Egypt,’ Le Monde Copte 18 (1990), 7-18; add early Western icons, B. Brenk, ‘Kultgeschichte versus Stilgeschichte: von der “raison d’être” des Bildes im 7. Jahrhundert in Rom,’ in Uomo e spazio nell’ Alto Medioevo, 2 vols. (Spoleto, 2003), 2: 972-1053. 37 Av. Cameron, ‘The Language of Images: The Rise of Icons and Christian Representation,’ in The Church and the Arts, ed. D. Woods (Oxford, 1992), pp. 1-42, reprinted in her Changing Cultures in Early Byzantium (Aldershot, 1996), Ch. XII; L. Brubaker, ‘Icons before Iconoclasm?,’ in Morfologie sociali culturali in Europa fra tarda antichità e alto medioevo, ed. G Cavallo et al. (Spoleto, 1998), pp. 1215-54; M. Meier, Das andere Zeitalter Justinians (Göttingen, 2003), pp. 528-60. 38 For the texts see C.J.F. Dowsett, The History of the Caucasian Albanians by Movsēs Dasxuranci (Oxford, 1961), pp. 171-3; Thümmel, Frühgeschichte (see above, n. 4), pp. 154-71. 8 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 usually connected with them, probably should be looked at independently.39 However, we should not relate these objections to the iconoclastic activities in Palestine, although the two were already connected by the Byzantines themselves at the Second Council of Nicaea in AD 787.40 The famous edict of Yazid II (720-40), which was issued in the last months of 723,41 was clearly enforced only very briefly, and the Christian mosaics soon restored afterwards.42 Yazid was not an austere Muslim,43 and his iconoclastic outburst still remains unexplained,44 even though Islamic opposition to crosses and icons had already started before his caliphate.45 It cannot, in any way, be held responsible for the Byzantine querelle des images, even though Islam may have influenced the turn towards non-figurative art in Palestine among the Jews.46 Among the Christians, figurative mosaics remained visble in some monasteries well into the eighth century, but it seems that no new ones were laid after Yazid II.47 It is in the “pre-iconoclastic” decade, in the early 720s, that we first encounter the term eikônoklastês in a letter of the eunuch patriarch of Constantinople, Germanos.48 The term is not explained, and it seems therefore to be already current. The real clash between iconoclasts and iconodules started in Byzantium only in 726 and certainly accelerated from 730 onwards. Yet it does not 39 As is persuasively argued by A.B. Schmidt, ‘Gab es einen armenischen Ikonoklasmus? Rekonstruktion eines Dokuments der kaukasisch-albanischen Theologiegeschichte,’ in Das Frankfurter Konzil von 794, ed. R. Berndt, 2 vols. (Mainz, 1997), 2: 947-64. For the earlier view see P.J. Alexander, Religious and Political History and Thought in the Byzantine Empire (London, 1978), Chapter VII (‘An Ascetic Sect of Iconoclasts in Seventh Century Armenia,’ 1st ed. 1955); Thümmel, Frühgeschichte (see above, n. 4), pp. 150-4. 40 Mansi 13, 197A-200B, cf. Theophanes, Chronographia, I.401-2 De Boor; P. Speck, Ich bin’s nicht, Kaiser Konstantin ist es gewesen. Die Legenden von Einfluss des Teufels, des Juden und des Moslem auf den Ikonoklasmus (Bonn, 1990). 41 See now G. Bowersock, Mosaics as History (Cambridge, 2006), pp. 104-5, who persuasively refutes the conventional date of 721. 42 Schick, Christian Communities (see above, n. 16), pp. 209-10. 43 G. Fowden, Qusayr ‘Amra (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 2004), pp. 146-8. 44 For other such outbursts see F.B. Flood, ‘Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm and the Museum,’ Art Bulletin 84 (2002), 641-59 and idem, ‘Refiguring iconoclasm in the early Indian mosque,’ in Negating the Image (see above, n. 1), pp. 15-35. 45 More persuasively on the increasing Muslim hostility to icons and crosses, S.H. Griffith, ‘Images, Islam and Christian Icons: a Moment in the Christian/Muslim Encounter in Early Islamic Times,’ in La Syrie de Byzance à l’islam VII e-VIII e siècles, ed. P. Canivet and J.-P. ReyCoquais (Damascus, 1992), pp. 121-38. The explanation by Bowersock, Mosaics as History, (see above, n. 41), pp. 109-10 is hardly convincing. 46 Fine, Art & Judaism (see above, n. 16), pp. 121-3. 47 Schick, Christian Communities (se above, n. 15), pp. 183-9. 48 Germanos, Ep. 4 (= Patrologia Graeca 98.189B). For his correspondence see D. Stein, Der Beginn des byzantinischen Bilderstreites und seine Entwicklung bis in die 40er Jahre des 8. Jahrhunderts (Munich, 1980). J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 9 seem that the term was very popular in Byzantium, as it is mentioned only very intermittently, except for the Acts of the Council of Nicaea II, which decided in favour of the restoration and veneration of images. After the end of the iconoclastic struggle, which was won by the iconodules, the term is found mainly in connection with heretics, such as the Manicheans and Paulicians.49 In fact, the term is so rare that it is not to be found in the great Greek and Byzantine dictionaries from before the twentieth century, those of Stephanus, Ducange, and Sophokles.50 How, then, did the term become accepted in the West? What we now call the “iconoclastic struggle” certainly did not go unobserved in Italy and France.51 Several seventh-century synods had the question of the veneration of images on the agenda, and the Acts of the Second Council of Nicaea (AD 787) were translated into Latin several times.52 The Parisian Council of 825 even discussed the matter in detail, as it had become urgent again because of the prohibition of images by Claudius, the bishop of Turin.53 Yet, although the Acts of Nicaea II often use the term eikonôklastês, it does not occur in these early Latin texts, because Anastasius Bibliothecarius, the translator of the Acts of Nicaea, always uses iconas frangentes or confringentes. However, we do find the term iconoclasta in Anastasius’s Latin translation of Theophanes in his Chronographia tripartita (335, 9 de Boor), from where it was taken over by the Historia Miscella (Patrologia Latina 95, 1139A). 49 Theophanes, Chronographia, I.496 De Boor; Ps.Chrysostom, In Psalmum 118, PL 55.692, 701; Horos of Synodicon Orthodoxiae (AD 843, but actually of a somewhat later date), 84, ed. J. Gouillard, ‘Le Synodikon de l’Orthodoxie: édition et commentaire,’ Travaux et mémoires 2 (1967), 1-316, there 161-3 (date), 296 (text); Vita S. Ioannicii auctore Saba monacho, ed. J. van den Gheyn, in Acta Sanctorum, Nov., II.1 (Brussels, 1894), pp. 333-83, there p. 372; Ps. Johannes Damascenus, Epistula ad Theophilum imperatorem de sanctis et venerandis imaginibus, PL 95.373, 381, 384, 701. 50 H. Estienne, Thesaurus linguae Graecae, 5 vols. (Geneva, 1572 and later editions); Charles Du Chesne Du Cange, Glossarium ad scriptores mediæ & infimæ graecitatis, 2 vols. (Leiden, 1688); E.A. Sophocles, Greek lexicon of the Roman and Byzantine periods (Boston, 1870). 51 M. McCormick, ‘Textes, images et iconoclasme dans le cadre des relations entre Byzance et l’Occident carolingien,’ in Testo e immagine nell’ Alto Medioevo, 2 vols. (Spoleto, 1994), 1: 95-158; H.G. Thümmel, ‘Die Stellung des Westens zum byzantinischen Bilderstreits des 8./9. Jahrhunderts,’ in Crises de l’image religieuse, ed. O. Christin and D. Gamboni (Paris, 1999), p. 55-74 and Thümmel, Konzilien zur Bilderfrage (see above, n. 4), pp. 82-5, 95, and 285-8. 52 For the Greek and Latin texts see now E. Lamberz, ‘Stand und Perspektiven der Edition der Konzilsakten des frühen Mittelalters (692-880) in den “Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum”,’ Annali dell’Istituto storico italo-germanico in Trento 29 (2003), 421-36; J. Uphus, Der Horos des Zweiten Konzils von Nizäa 787: Interpretation und Kommentar auf der Grundlage der Konzilsakten mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Bilderfrage (Paderborn, 2004). 53 P. Boulhol, Claude de Turin: un évêque iconoclaste dans l’occident carolingien (Paris, 2002). 10 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 Although we do not find the term in the intervening period, iconoclasta suddenly turns up in England around 1420. Here the problem of venerating images had become acute through the anti-image writings of John Wyclif (c. 1320-1384), whose views became radicalised by his followers, the Lollards.54 Against Wyclif and John Hus (1369-1415), Thomas Netter (or Waldensis: ca. 1372-1431), a Carmelite provincial, published his very learned Doctrinale antiquitatum fidei (ca. 1420), which included a treatise De cultu imaginum. For his arguments Thomas looked both to the Bible and to the Church Fathers, and thus he also became interested in the Byzantine struggle. He searched the then available sources, amongst which he naturally found the Chronicon of the then popular Sigebert of Gembloux (ca. 1020-1112), but he also quotes from a book De dogmatibus by two Dominicans, Giovanni Dominici (ca. 1350-ca. 1420) and Thomas Anglicus (ca. 1400), which evidently refers to the iconoclastic period: “execratores imaginum sub nomine iconoclastarum, latine fractorum imaginum” and “ideo iconoclastae, idest, Imaginifragi dicebantur.”55 Unfortunately, I have been unable to trace this book, but it is noteworthy that the citations show that the authors were conscious of the novelty of the term and thought it necessary to translate it. In any case, we can be fairly certain that around this time the term is still very new, as none of the current dictionaries of Medieval Latin contains the term.56 Although Netter’s work started to be printed in Paris in 1521, this edition was not yet available for the polemics about the images that started in Wittenberg on 27 January 1522 with the appearance of Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt’s Von abthuung der bylder [On the removal of images],57 which was 54 W.R. Jones, ‘Lollards and Images: The Defense of Religious Art in Later Medieval England,’ Journal of the History of Ideas 34 (1973), 27-50; Feld, Ikonoklasmus des Westens (see above, n. 9), pp. 85-90; Schnitzler, Ikonoklasmus–Bildersturm (see above, n. 2), pp. 85-8; S. Stanbury, ‘The Vivacity of Images: St Katherine, Knighton’s Lollards, and the Breaking of Idols,’ in Images, Idolatry, and Iconoclasm in Late Medieval England, ed. J. Dimmick et al. (Oxford, 2002), pp. 131-50. 55 Thomas Waldensis, Doctrinale antiquitatum fidei Catholicae Ecclesiae adversus Wiclefitas et Hussitas ad vetera exemplaria recognitum & notis illustratum, ed. B. Blanciotti, 3 vols. (Venice, 1757-59; reprinted in one volume: Farnborough, 1967), 3: 902-72, there 906. 56 The exception seems to be J.W. Fuchs, Lexicon Latinitatis Nederlandicae medii aevi, 8 vols. (Leiden, 1970-2005), 4: 2287, referring to Cronica et cartularium monasterii de Dunis (Brugge, 1864), p. 97 as a text of ca. 1488, which is quoted by Schnitzler, Ikonoklasmus–Bildersturm (see above, n. 2), p. 22 note 51. However, this is a mistake and the text is clearly much later, as the quoted sentence begins with: Anno Domini 1566. 57 For Karlstadt see R. Sider, Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt: the development of his thought 1517-1525 (Leiden, 1974), pp. 148-73; A. Zorzin, Karlstadt als Flugschriftenautor (Göttingen, 1990); E. Ullmann, ‘Die Wittenberger Unruhen, Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt und die Bilderstürme in Deutschland,’ in L’Art et les révolutions, 8 vols. (Strassbourg, 1992), 4: 117-26. J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 11 so successful that it was reprinted in the same year. In that same spring, the Catholic theologian Johannes Eck published a pamphlet with a defense of the images (On not removing images of Christ and the saints) without, however, yet knowing Karlstadt’s work, but on April 2 the Dresdner court chaplain Hieronymus Emser (1478-1527) already issued a pamphlet against Karlstadt (That one should not remove images of the saints from the churches nor dishonour them, and that they are not forbidden in Scripture).58 For his arguments he drew on Netter without mentioning him, but there can be little doubt about his debt, as two years later he explicitly mentions our Carmelite in a treatise on the Eucharist against Luther.59 Netter will remain an important source for the Catholic theologians in the fierce debates about images of that century,60 and, directly or indirectly, he seems to be responsible for the occurrence of the term iconoclasta in the texts of Catholic theologians,61 which starts with Emser and Eck, but gradually also reaches the lay people.62 58 For all three pamphlets see now B. Mangrum and G. Scavizzi, A Reformation debate: Karlstadt, Emser, and Eck on sacred images: three treatises in translation (Ottawa, 1991). 59 H. Smolinsky, ‘Reformation und Bildersturm. Hieronymus Emsers Schrift gegen Karlstadt über die Bilderverehrung,’ in Reformatio ecclesiae, ed. R. Bäumer (Paderborn, 1980), pp. 427-40, there pp. 437-8. 60 M. Harvey, ‘The Diffusion of the Doctrinale of Thomas Netter in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries,’ in Intellectual Life in the Middle Ages: Essays presented to Margaret Gibson, ed. L. Smith and B. Ward (1992), pp. 281-94; note also J. Molanus, De historia SS. imaginum et picturarum pro vero earum usu contra abusus, libri quatuor, 2nd ed. (Louvain, 1594 [1st ed. 1570]), p. 4. 61 Perhaps understandably, I have not been able to find the term in sixteenth-century Protestant theologians. 62 Theologians: H. Emser, Missae Christianorum contra Luteranam missandi formulam assertio (Dresden, 1524) no page number = H. Emser, Schriften zur Verteidigung der Messe, ed. Th. Freudenberger (Münster, 1959), p. 24: Constantium Augustum Iconoclasten; J. Eck, Enchiridion locorum communium adversus Lutherum, & alios hostes ecclesiae (Lyon, 1572 [Landshut, 1525]), p. 159 = Enchiridion etc., ed. P. Fraenkel (Münster, 1979), p. 193: Graeci appellarunt haereticos illos Iconoclastas, id est, fractores imaginum and Homiliarum Tomus Secundus (Paris, 1597 [1533]), p. 206: Catabaptistarum, sacramentariorum, Iconoclastrarum (sic), & quid denique non?; A. Catharinus,Opuscula (Lyon, 1542), pp. 61, 23; Disput. 141, 3 (non vidi: I owe this reference to Marc van de Poel, who refers to R. Hoven, Lexique de la prose latine de la Renaissance, 2nd ed. (Leiden, 2006), s.v., but also notes the absence of the term in all other relevant dictionaries); J. Cochlaeus, De sanctorum invocatione & intercessione, deque imaginibus & reliquiis eorum pie riteque colendis (Ingolstadt, 1544), no page numbers but often in the text; S. Hosius, Verae, Christianae, Catholicae que doctrinae solida propugnatio (Cologne, 1558), p. 181: Sententia Synodi Nicaenae contra Iconoclastas. Lay people: V. Despodt, Gentse grafmonumenten en grafschriften tot het einde van de Calvinistische republiek (1584) (Gent, 2001) = http://www.ethesis.net/gent_ grafmonumenten/repertorium.pdf, no’s 1.6/084-5 (AD 1601). 12 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 Given the fierce Huguenot attack on images,63 it may not be surprising that in French the term ‘iconoclaste’ already appears in 1557.64 However, the Latin spelling was still adopted in the Scottish translation of John Leslie’s (1526-96) Historie of Scotland, which appeared in 1596, but was originally published in Latin in Rome in 1578. Here the term is clearly a direct reference to the Iconoclastic Struggle: “ . . . a counsel of thrie hunder and fiftie Bischopis haldne at Nice (i.e. Nicaea II in AD 787)65 against the secte of Jmagebrekeris, thair name Jconoclastæ, from Jcon, quhilke in greke is namet ane Jmage in Scotis.”66 It is clear that here the term is still in Latin, and it was not until the iconoclasm during the era of Cromwell that the first occurrences of both ‘iconoclast’ and ‘iconoclastic’ appear,67 despite the fact that, strangely enough, the Greek term made a comeback in the seventeenth century in the titles of works by Milton and the Quaker George Fox.68 In the title of books I note its first appearance in 1671, perhaps still a fruit of the Cromwell years,69 whereas only from the 1870s onwards it occurs in the titles of articles, just like ‘iconoclastic,’70 which starts to appear in titles of books only in 1930.71 In its meaning of somebody who assails or attacks accepted and cherished opinions and 63 R. Sauzet, ‘L’iconoclasme dans le diocèse de Nîmes au XVIe et au début du XVIIe siècle,’ Revue de l’histoire de l’église de France 66 (1980), 5-16; O. Christin, Une révolution symbolique: l’iconoclasme huguenot et la reconstruction catholique (Paris, 1991); L. Réau, Histoire du vandalisme: les monuments de étruits de l’art français, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1994), pp. 73-133. 64 Trésor de la langue française, 9 (Paris, 1981): 1062. Note also its appearance in Italian in 1614: T. de Mauro, Grande dizionario italiano dell’uso, 3 (Turin, 1999): 385. 65 For the Council see Nicée II (see above, n. 27); Thümmel,Konzilien zur Bilderfrage (see above, n. 4), pp. 87-198; M. Squillace, ed., Il Concilio Ecumenico Niceno II e l’iconografia mariana in Calabria (Catanzaro, 1990). 66 J. Leslie, Historie of Scotland, Translated in Scottish by James Dalrymple (Regensburg, 1596), p. 269 = The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, ed. E.G. Cody and W. Murison, 2 vols. (Edinburgh 1888-95), 1: 269. 67 Cromwell: J. Spraggon, Puritan Iconoclasm during the English Civil War (Woodbridge, 2003). ‘Iconoclast’: W. Hinde, A faithfull remonstrance of the holy life and happy death of Iohn Bruen of Bruen-Stapleford (London, 1641), pp. xxvi, 80; J. Taylor, The real presence and spirituall of Christ in the blessed sacrament proved against the doctrine of transubstantiation (London, 1654), p. xii §28. 315. ‘Iconoclastic’: R. Baillie, Ladensium autokatakrisis, the Canterburians self-conviction (Amsterdam, 1640), p. 53: ‘Iconoclasticke and iconomachian hereticks.’ 68 J. Milton, Eikonoklastes (London, 1649); G. Fox, Iconoclastes (s.l., 1671). 69 T. Anderton, The history of the iconoclasts dvring the reign of the emperors Leo Isavricvs etc. (s.l., 1671). 70 T.G.A, ‘The Iconoclast of Sensibility,’ Christian disciple and theological review 7.6 (1873), 691; ‘Iconoclastic,’ Blackwood’s Edinburgh magazine 113 (1873), issue 687, 54. 71 E. Martin, A history of the iconoclastic controversy (London, 1930). Was Martin perhaps inspired by the nearly contemporaneous appearance of G. Ostrogorsky, Studien zur Geschichte des byzantinischen Bilderstreites (Breslau, 1929)? J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 13 institutions, ‘iconoclast’ emerges in the 1850s, which is slightly earlier than is suggested by the Oxford English Dictionary2 (s.v.).72 It is a different story with ‘iconoclasm,’ which seems to have emerged in the middle of the sixteenth century,73 and it seems reasonable to surmise that the Latin term iconoclasmus has given rise to the English ‘iconoclasm.’ The term first appears in 1797 as used by the polyglot and political radical William Taylor (1765-1835), that is, during the French Revolution, a time that is also characterised by iconoclasm of, especially, church objects,74 even though Taylor uses the term in the context of the Protestant resistance to images.75 It fits this date that in French the term ‘iconoclasme’ does not occur in Diderot’s Encylopédie nor in the fourth edition of 1762 of the Dictionnaire de L’Académie française, but appears first in 1832.76 In the titles of articles, ‘iconoclasm’ makes its first appearance in 1846,77 but in the title of books it does not show before 1885 in its general sense and, with regard to the Byzantine controversy, only in 1973.78 What can we conclude from our investigation so far? My first conclusion is that ‘iconoclasm’ is a relatively late term, both in its application to the Byzantine Querelle des images and to its more general meaning. Gibbon, the leading historian of Byzantium during the Enlightenment, when the iconoclastic period drew much attention,79 did not yet know the term and consequently 72 B. Blood, The Bride of the Iconoclast (Boston, 1854); B. Grant, A full report of the discussion, between the Rev. Brewin Grant and “Iconoclast” [i.e. C. Bradlaugh] in the Mechanics’ hall, Sheffield, on the 7th, 8th, 14th, & 15th June, 1858 (London, 1858). 73 P. Busaeus, Avthoritatvm Sacrae Scriptvrae et sanctorvm patrvm, qvae in catechismo doctoris Petri Canisii theologi Societatis Iesv citantur, 4 vols. (Venice, 1571), 1: index s.v. Claudius Taurinensi episcopus quî per quem de iconoclasmo oppugnatus and Xenaiae cuiusdam Persae hypocrisis & Iconoclasmus; L. Froidmont, Causae Desperatae Gisb. Voetii etc. (Antwerp, 1636), p. 14: in Belgio post Iconoclasmum anni 1566; D. van Papenbrock, in Acta Sanctorum, Iun. 1 (Antwerp, 1695): 946: Licet enim vetera omnia dejecerit iconoclasmus. 74 S. Idzerda, ‘Iconoclasm during the French Revolution,’ American Historical Review 60 (1954), 13-26; Feld, Ikonoklasmus des Westens (see above, n. 9), pp. 253-76; R. Wrigley, ‘Breaking the Code: Interpreting Iconoclasm in the French Revolution,’ in Reflections of Revolution: Images of Romanticism, ed. A. Yarrington and K. Everest (Routledge, 1993), pp. 182-95; Réau, Histoire du vandalisme (see above, n. 63), pp. 233-551; R. Clay, ‘Theft and iconoclasm: the treatment of Catholic objects in eighteenth-century France,’ Oxford Art Journal 26 (2003), 1-22. 75 W. Taylor, ‘Foreign literature,’ The Monthly Review, New Series 24 (1799), 506-13, there 512. 76 Trésor de la langue française, vol. IX, 1062. Note that iconoclasmo is still absent from the Vocabulario universale italiano, 3 (Naples, 1834): 599. 77 J. Ingram, ‘Iconography and iconoclasm,’ Archaeological Journal 1 (1846), 131-4. 78 I. Browne, Iconoclasm and whitewash, and other papers (New York, 1885); S. Gero, Byzantine iconoclasm during the reign of Leo III (Louvain, 1973). 79 J. Irmscher, ‘Der byzantinische Bilderstreit in der Geschichtsschreibung der Aufklärung,’ in Der byzantinische Bilderstreit, ed. J. Irmscher (Leipzig, 1980), pp. 170-92. 14 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 did not study the eighth and ninth centuries of Byzantine history from an iconoclastic perspective.80 That we do so today is a fairly recent development, which seems to have started in the Anglophone world only in the 1950s with the well-known papers of Francis Dvornik and Ernst Kitzinger.81 After this hesitant beginning the use of the term has exploded in recent decades and become a very “sexy” subject, as the many studies in this field eloquently attest, witness the following rough count of the terms ‘iconoclast(ic)’ and ‘iconoclasm’ in the titles of books and articles:82 Years # of Books # of Articles 1850-1875 1876-1900 1901-1925 1926-1950 1951-1975 1976-2000 2001-2007 1 2 2 6 21 46 20 1 9 14 14 32 114 80 This development has at least three disadvantages. First, as already noted, the term has promoted a tendency to view the eighth and ninth centuries in Byzantium very much from an iconoclastic point of view: it thus helped to construct a period rather than simply define it.83 Secondly, the term has promoted the tendency to group together all kinds of phenomena, such as the Byzantine opposition to the representation of Christ, the Islamic opposition to the representation of people, the careful removing of some parts of images by Christians in eighth-century Palestine 80 J.D. Howard-Johnston, ‘Gibbon and the middle period of the Byzantine Empire,’ in Edward Gibbon and Empire, ed. R. McKitterick and R. Quinault (Cambridge, 1997), pp. 53-77. 81 F. Dvornik, Photian and Byzantine Ecclesiastical Studies (London, 1974), Ch. V (‘The Patriarch Photius and Iconoclasm,’ 1st ed. 1953); E. Kitzinger, The Art of Byzantium and the Medieval West (Bloomington and London, 1976), pp. 90-150, 390-1 (‘The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm,’ 1st ed. 1954, which heavily drew on Von Dobschütz, Christusbilder [see above, n. 35]). 82 I have counted the books via HOLLIS (Harvard) and the articles via PiCarta. Admittedly, this is a rough estimation, as it is regularly hard to decide what counts as an article, but the trend seems clear. 83 This is rightly noted by H. Bredekamp, Kunst als Medium sozialer Konflikte. Bilderkämpfe von der Spätantike bis zur Hussitenrevolution (Stuttgart, 1975), pp. 114-6. J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 15 and the vandalism of images during the Reformation, under one umbrella term. Moreover, the availability of the term has also promoted the tendency to see causal correlations between rather different phenomena. Thus Armenian opposition to images becomes combined with Yazid’s edict and the Byzantine opposition to representing Christ without any proof that there was a real connection between these movements. Last and certainly not least, the anti-image writings of Calvin, Zwingli, and Luther, as well as the iconoclastic vandalism of the early Protestants, have been well studied and their effects on the development of Western theology and art often analysed.84 Yet the concentration on the “events” of iconoclasm have often obscured the fact that, in general, the churches of the Reformation have preserved medieval art much better than the Catholic churches. This insight is only gradually winning ground, even though already in 1916 the German art historian Georg Dehio had noted that medieval altars had been much better preserved in Lutheran countries than anywhere else.85 More recently, we have had a series of studies on those Lutheran countries,86 but a full survey was hardly possible. I may perhaps be forgiven to say that the efforts of my Groningen colleagues Justin Kroesen and Regnerus Steensma enable us now to sketch a much more precise picture.87 Their study of the village church in Western Europe confirms the judgment of Dehio, but it also demonstrates that even Anglican and Calvinist churches often have preserved interesting pieces of medieval art, be it in the form of the retables, baptismal fonts, pulpits, screens or sacred vessels. The reasons for this development naturally first depend on the theological views of the leading lights of the Reformation. Although Luther declined the 84 See especially W. Hofmann, ed., Luther und die Folgen für die Kunst (Munich and Hamburg, 1983); C. Eire, War against the idols: the reformation of worship from Erasmus to Calvin (Cambridge, 1986); R.W. Scribner and M. Warnke, eds., Bilder und Bildersturm im Spätmittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit (Wiesbaden, 1990); S. Michalski, The Reformation and the visual arts: the Protestant image question in Western and Eastern Europe (London, 1993); wonderfully illustrated, C. Dupeux et al., eds., Bildersturm. Wahnsin oder Gottes Wille? (Munich, 2000); P. Blickle, ed., Macht und Ohnmacht der Bilder: reformatorischer Bildersturm im Kontext der europäischen Geschichte (Munich, 2002); J.L. Koerner, The Reformation of the Image (London, 2003); Belting, Das echte Bild (see above, n. 20), pp. 173-216; W. van Asselt, ‘The Prohibition of Images and Protestant Identity,’ in idem et al., eds., Iconoclasm and Iconoclash (Leiden, 2007), pp. 299-311. 85 G. Dehio, ‘Die Krisis der deutschen Kunst im sechzehnten Jahrhundert,’ Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 12 (1916), 1-16, there 8-9. For Dehio see Erich Hubala, ‘Georg Dehio 1850-1932: Seine Kunstgeschichte der Architektur,’ Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 46 (1983), 1-14; B. Herrbach, ‘Georg Dehio: Verzeichnis seiner Schriften,’ Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 47 (1984), 392-9. 86 J.M. Fritz, ed., Die bewahrende Kraft des Luthertums: Mittelalterliche Kunstwerke in evangelischen Kirchen (Regensburg, 1997). 87 J.E.A. Kroesen and R. Steensma, Het middeleeuwse dorpskerkinterieur / The Interior of the Medieval Village Church (Louvain, 2004). 16 J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 veneration of images, he was fiercely against Bildersturm and in some ways rather favoured images in the church. His point of view created a climate that has led to the preservation of relatively much medieval art and liturgical objects in Lutheran churches. In some cases, this happened because the Lutherans continued to use certain pre-Reformation parts of the church, such as the pulpit, the baptismal font and the high altar for the Eucharist. In other cases, they just let objects stand without using them any longer. That is why quite a few side altars have survived in Lutheran churches. These were no longer necessary after the abolishment of the cult of the saints and the masses for the dead, but people were attached to them and therefore left them where they were. Finally, some parts could be preserved by giving them a different function. For example, in Northern Germany the tabernacle, which was used to keep the hosts after the mass, was now used to keep the liturgical vessels. In England, Kings Henry VIII and Edward VI introduced a regime that was highly detrimental for the preservation of images, paintings, and liturgical vessels of silver and gold.88 That is why, as regards medieval elements, we mainly find pews, fonts, pulpits, screens, roods, and rood lofts, but not altars, crosses, images, and retables. Consequently, Anglican churches often look more Protestant than those in Lutheran countries. Finally, Calvin and Zwingli were very much against images in the churches, and that is why their followers in the Netherlands and Switzerland were the most radical in cleaning out the Calvinist churches. Yet even here some medieval elements have been preserved, especially fonts and pews, sometimes even with representations of Mary or Saints.89 Among the Catholics, on the other hand, in the two centuries after the Reformation we find a much more gradual removal and destruction of the medieval heritage. Yet the church interiors were not left intact. As the Council of Trent had ordered a renewal of the liturgy in order to involve the faithful more in the church services, everything that impeded a good view of the high altar was removed. Moreover, the abolishment of private masses caused the taking away of many side altars, and the restructuring of the high altar caused the replacement of the Gothic retables by Renaissance and, later Baroque ones. Secondly, this process was accelerated by the ornateness of the Baroque period, which transformed the much more simple medieval churches into the familiar interiors of many Catholic churches of today.90 88 The classic study is E. Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars, 2nd ed. (London and New Haven, 2005). 89 For this brief survey see J.E.A. Kroesen, ‘Tussen Bugenhagen en Borromaeus: de paradox van de conserverende Reformatie,’ Nederlands Theologisch Tijdschrift 59 (2005), 89-105. 90 See, for example, J. Bourke, Baroque churches of Central Europe, 2nd ed. (London, 1962); P. and C. Cannon-Brookes, Baroque churches (New York, 1969). J.N. Bremmer / Church History and Religious Culture 88 (2008) 1-17 17 Although this process eventually was much more destructive of medieval art than the iconoclasm of the Reformation, it has received far less attention from art historians.91 Iconoclastic events evidently appeal much more to the contemporary imagination with its postmodernist fascination for fragmentation. Yet outbursts of destruction may in the end be far less damaging than a process of creeping destruction. There is a lesson here to be learned.92 Prof. Dr. J.N. Bremmer, Department of Religious Studies & History of Christinianity, Oude Boteringestraat 38, NL-9712 GK Groningen, The Netherlands; J.N.Bremmer@rug.nl 91 But see S. Kummer, ‘“Doceant episcopi”. Auswirkungen des trienter Bilderdekrets im römischen Kirchenraum,’ Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 56 (1993), 508-33 (with previous bibliography); C. Hecht, Katholische Bildertheologie im Zeitalter von Gegenreformation und Barock: Studien zu Traktaten von Johannes Molanus, Gabriele Paleotti und anderen Autoren (Berlin, 1997); G. Knox, ‘The Unified Church Interior in Baroque Italy: S. Maria Maggiore in Bergamo,’ Art Bulletin 82 (2000), 679-99. 92 Earlier versions of this paper were given at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (Williamstown), the Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles), and the College Art Association (New York) in the academic year 2006-2007. I am grateful to Tom Crow and Charles Salas for inviting me to give this paper, and to Charles Barber, Robin Cormack, Barry Flood, Ronald Hutton, Justin Kroesen, Marc van de Poel and, in particular, Erich Lambertz for comments and information. Kristina Meinking kindly corrected my English.