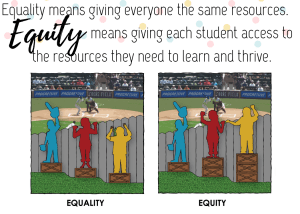

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF TAXATION • FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS • 1. Definition of Taxation – The power by which the sovereign raises revenue to defray the necessary expenses of government. 1 Another definition • That the author suggested is that it is an inherent power of the state vested in the legislative body of the government to enforce proportional contributions for persons, properties or rights to generate revenues which is use for the pubic expenses of the government. 2 A tax is • a payment in money • required by a government • that is unrelated to any specific benefit or service received from the government. 3 Other definition… A tax is … • a financial, mandatory, nonequivalent, non-specific charge or other levy imposed on a taxpayer by a state. • The tax is implemented by law. • The failure to pay taxes is punishable by law. • The taxes can be paid regularly or occasionally based on certain conditions stipulated by the tax legislation. 4 The three criteria necessary to be a tax are • the payment is required (by the law) – free rider theorem of public goods • imposed by a government • not tied directly to the benefit received by the taxpayer. 5 Sources of finance – Tax = MAIN SOURCE – User charges • Prices charged for the delivery of certain public goods and services • Examples: Toll roads, public swimming pools – Administrative fees • Definition of service/benefit is broad & imprecise • Examples: TV licences, parking tickets – Borrowing 6 7 8 Scope of power of taxation The power of taxation is comprehensive, plenary, unlimited, and supreme. This power is however, subject to inherent and constitutional limitations. 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 (1) Ease of Collection and (2) Ease of Compliance To successfully implement a tax policy, it is necessary to incur the costs associated with administering and enforcing it Given that society must incur these costs, it wants to get the most possible revenue at the least possible cost Requires that individuals be able to calculate tax bills fairly easily and that it be difficult for individuals to hide information on taxable assets 31 start reporting!!!!! Tax Principles Economists believe that any broad-based tax should possess five characteristics: (1) Ease of collection (2) Ease of compliance (3) Flexibility (4) Promotion of economic efficiency (5) Promotion of end-results equity 32 Ease of collection (direct adminis. cost) • CIT, VAT – 2% of total tax revenue • Payroll Tax – 1 % • Bad results for… (why? Due to very low tax rates) – PIT – self employed persons – 30 % – Road tax – 5 % – Heritage tax (now abolished) - !169 % 33 Ease of compliance (indirect adminis. cost) in Czech Republic • CIT, VAT – 5% of total tax revenue • Payroll Tax – 1 % • PIT – self employed persons – 30 % • Road tax – 20 % (very low tax rates) 34 Tax Principles (3) Flexibility - Tax policy is a primary tool of macroeconomic policy (i.e. economic stabilization) - To be able to respond quickly to address potential difficulties in the economy, tax authorities must be able to change tax liabilities easily and quickly and those changes must quickly be felt throughout the economy 35 Tax Principles (3) Flexibility (II) 36 Tax Principles (4) Economic Efficiency Individuals must face same prices for economy to reach Pareto-optimal outcome Broad-based taxes are distorting (i.e. drive wedge between price paid by consumer and prices kept by firms) so they violate this property The goal then is to design a tax that introduces the least distortion and keeps society as close to the Paretooptimal outcome as possible (5) End-Results Equity Tax policy is designed to work with redistribution programs to achieve this goal 37 Six Main Taxes (1) (1) A personal income tax Tax on income received by individuals Typically collected from firms who withhold pay Tax liability calculated once a year and refund or extra payment made depending on whether enough was withheld (2) A payroll tax Tax levied on the wage and salary component of income Half tax collected from employers / half from workers Earmarked for Social Security in US (3) A corporate income tax Tax levied on accounting profits of corporations 38 Six Main Taxes (2) (4) An excise tax Tax on the sale of a single product (e.g. gasoline, alcohol, cigarettes) Designed to reduce consumption of good (5) A property tax Tax on value of items of wealth – usually residential, commercial and industrial properties Levied on owner of property Value assessed periodically by tax authorities (6) A value-added tax Tax on value added of firms (which is the difference between sales revenue and input purchases) Levied on firms 39 The Six Main Taxes (3) Use of the six main taxes - Governments in Europe also use personal and corporate income taxes, payroll taxes (to support social security payments) and property taxes - They levy a value-added tax on businesses - Recently, advocates have argued for a personal consumption tax rather than a personal income tax → Biggest difference is that it would allow individuals to subtract saving from income before calculating tax bill (because consumption = income - saving) 40 The Ability-to-Pay Principle - - Dates from Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill in late 1700s and early 1800s Holds that people must be willing to sacrifice for the public good Gave rise to view of taxes as necessary evil Key question: How to determine what people should sacrifice? Two potential approaches based on ability to pay - Horizontal Equity: Two people deemed equal in every relevant economic dimension should pay same tax - Vertical Equity: It is permissible to tax unequals unequally 41 The Ability-to-Pay Principle continued - - - Both principles raise important and difficult questions In what sense are people to be deemed to be equal or unequal? How unequally can unequal be taxed? The issue of horizontal equity is the quest for the ideal tax base (i.e. the item to be taxed) People with identical tax bases will pay identical tax bill The issue of vertical equity is the quest for the ideal tax structure, as defined by chosen tax rates and deductions Differences in chosen tax rates and deductions make it so that different people pay different tax bills 42 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base (OPTIONAL) - Robert Haig (1921) and Herbert Simons (1938) proposed a method of thinking about optimal tax base that relied on three principles: (1) People ultimately bear the burden of taxation (2) People sacrifice utility when they bear the burden of taxation Horizontal equity: Two people with equal utility before tax should have equal utility after tax Vertical equity: If person has more utility than another before tax they should also have more after tax (3) The ideal tax base is the best surrogate measure of utility Because utility cannot be measured, society must rely on something else, which should be best surrogate 43 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base Continued (OPTIONAL) Haig–Simons income Argues that the best surrogate for utility is the increase in purchasing power during the year YHS = consumption + change in net worth = C + ∆NW Concludes that people with the same YHS should be considered equals and should pay the same tax because they will sacrifice the same utility Once YHS is accepted as ideal tax base it implies that the optimal tax structure is the broadest possible personal income tax → This requirement is never met in practice 44 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base Continued (OPTIONAL) - Under the Haig–Simons definition of income, there are a number of distinctions that should not matter (but usually do) Factors that should be treated the same, but usually are not Sources of Income Uses of income - Personal income and capital gains (portion of capital gains usually excluded from tax base) - Earned and unearned income (receipt of transfer payments usually excluded from tax base) - Different sources of earned income (interest earned on savings and fringe benefits usually excluded) - Consumption and saving (saving usually excluded) - Various forms of consumption (medical care, mortgage interest payments, etc. usually excluded) - Form of capital gains (accrued capital gains usually excluded, realized usually included) 45 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base Continued (OPTIONAL) - - These differences usually exist because policymakers often use tax policy to try to promote social ends which might run counter to the concept of horizontal equity Business expenses should be excluded because they subtract from purchasing power out of income Calculation of YHS must be indexed to inflation because increasing prices reduces purchasing power Conclusion: Combined, these facts suggest that the ideal tax base is (YHS - business expenses), indexed for inflation 46 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base Continued (OPTIONAL) Haig-Simons income and utility Is this a good surrogate measure of utility? Almost certainly not! Whether income is good measure of utility depends on whether people are identical People receive utility from income and leisure Income comes from work and leisure comes from not working If every person has same preference for income and leisure and same opportunities (i.e. same wage) they will choose same point and have same utility In such a case, income would be a good surrogate for utility 47 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base Continued (OPTIONAL) - But people do not have identical tastes and opportunities - Suppose people earn different wages - Person with higher wage can receive higher utility with same income by taking more utility (i.e. can earn same income with fewer hours work) - Suppose people have different tastes - Person with stronger preference for consumption works more and earns more income but both are on second indifference curve which represents same utility 48 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base Continued (OPTIONAL) Consumption as the ideal tax base Recognizes that consumption is not a perfect surrogate measure of utility but is likely better than income Consumption most directly generates utility Consumption changes over time are more directly tied to utility changes over time than are income changes over time Implication is that to meet the concept of horizontal equity, two people with equal lifetime consumption before tax should have equal lifetime consumption after tax 49 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base Continued (OPTIONAL) - - This suggests that tax should be annual tax on consumption rather than annual tax on income Two people with same lifetime income might have very different lifetime consumption due to differences in annual consumption/savings decisions Note that it would be possible to design an annual income tax that would be equivalent to an annual consumption tax Would require allowing people to subtract saving from income, which would actually make it a consumption tax 50 Horizontal Equity: The Ideal Tax Base (OBLIGATORY) Musgrave’s view of horizontal equity Argues that questioning whether income or consumption tax is better is the wrong question Instead, believes that horizontal equity should only consider whether taxes discriminated against people in inappropriate ways Either income or consumption tax is appropriate surrogate for utility so long as people are not treated differently based on gender, race, religion, etc. Society should just accept one type of tax and then worry more about the specific tax structure (i.e. vertical equity) 51 Vertical Equity - - - This is the quest for distributive justice, which generates heated debate without a satisfactory conclusion Key question: Should tax structure be progressive, proportional, or regressive Let YhHS and Th be individual h’s income and tax burdens → If Th/ YhHS increases as YhHS increases, tax is progressive → If Th/ YhHS is constant as YhHS increases, tax is proportional → If Th/ YhHS decreases as YhHS increases, tax is regressive Societies tend to have a strong preference for proportional or progressive taxes 52 Progressive, Proportional, and Regressive Taxes • Proportional tax – Percentage of taxpayers income • Progressive tax – Larger percentage of income as income rises • Regressive tax – Smaller percentage of income as income rises 53 Progressive, Proportional, and Regressive Taxes 54 Income and Consumption over Life Cycle 55 Measuring of Consequences of Taxation to Income Distribution I. Lorenz Curve 56 Measuring of Consequences of Taxation to Income Distribution II. Gini‘s Coefficient G is usually 0.2 to 0.5 Consequence of Linear or Progressive Tax: Gini before tax > Gini after tax 57 Measuring of Consequences of Taxation to Income Distribution III. 58 59 60 Tax Incidence • Two main concepts of how a tax is distributed: – Statutory incidence – who is legally responsible for tax – Economic incidence – the true change in the distribution of income induced by tax. – These two concepts differ because of tax shifting. 61 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Only people can bear taxes – Business paying their fair share simply shifts the tax burden to different people – Can study people whose total income consists of different proportions of labor earnings, capital income, and so on. – Sometimes appropriate to study incidence of a tax across regions. 62 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Both Sources and Uses of Income should be considered – Tax affects consumers, workers in industry, and owners – Economists often ignore the sources side 63 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Incidence depends on how prices are determined – Industry structure matters – Short- versus long-run responses 64 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Incidence depends on disposition of tax revenue – Balanced budget incidence computes the combined effects of levying taxes and government spending financed by those taxes. – Differential tax incidence compares the incidence of one tax to another, ignoring how the money is spent. • Often the comparison tax is a lump sum tax – a tax that does not depend on a person’s behavior. 65 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Tax progressiveness can be measured in a number of ways – A tax is often classified as: • Progressive • Regressive • Proportional – Proportional taxes are straightforward: ratio of taxes to income is constant regardless of income level. 66 Tax Incidence: General Remarks • Can define progressive (and regressive) taxes in a number of ways. • Can compute in terms of – Average tax rate (ratio of total taxes total income) or – Marginal tax rate (tax rate on last dollar of income) 67 Tax Incidence: General Remarks (optional) • Measuring how progressive a tax system is present additional difficulties. Consider two simple definitions. – The first one says that the greater the increase in average tax rates as income rises, the more progressive is the system. v1 T1 I1 T0 I0 I1 I 0 68 Tax Incidence: General Remarks (optional) – The second one says a tax system is more progressive if its elasticity of tax revenues with respect to income is higher. – Recall that an elasticity is defined in terms of percent change in one variable with respect to percent change in another one: %T v2 %I T1 T0 T0 I1 I0 I0 69 Tax Incidence: General Remarks (optional) • These two measures, both of which make intuitive sense, may lead to different answers. • Example: increasing all taxpayer’s liability by 20% 70 Partial Equilibrium Models • Partial equilibrium models only examine the market in which the tax is imposed, and ignores other markets. • Most appropriate when the taxed commodity is small relative to the economy as a whole. 71 Partial Equilibrium Models: Per-unit taxes • Unit taxes are levied as a fixed amount per unit of commodity sold – Excise tax on cigarettes, for example, is 2.37 CZK per piece; sparkling wine 2340.- CZK per 1 hl. • Assume perfect competition. Then the initial equilibrium is determined as (Q0, P0) in Figure 1. 72 Partial Equilibrium Models: Per-unit taxes • Next, impose a per-unit tax of $u in this market. – Key insight: In the presence of a tax, the price paid by consumers and price received by producers differ. – Before, the supply-and-demand system was used to determine a single price; now there is a separate price for each. 73 Partial Equilibrium Models: Per-unit taxes • How does the tax affect the demand schedule? – Consider point a in Figure 1. Pa is the maximum price consumers would pay for Qa. – The willingness-to-pay by demanders does NOT change when a tax is imposed on them. Instead, the demand curve as perceived by producers changes. – Producers perceive they could receive only (Pa–u) if they supplied Qa. That is, suppliers perceive that the demand curve shifts down to point b in Figure 1 – . 74 Figure 1 75 Partial Equilibrium Models: Per-unit taxes • Performing this thought experiment for all quantities leads to a new, perceived demand curve shown in Figure 2. • This new demand curve, Dc’, is relevant for suppliers because it shows how much they receive for each unit sold. 76 Figure 2 77 Partial Equilibrium Models: Per-unit taxes • Equilibrium now consists of a new quantity and two prices (one paid by demanders, and the other received by suppliers). – The supplier’s price (Pn) is determined by the new demand curve and the old supply curve. – The demander’s price Pg=Pn+u. – Quantity Q1 is obtained by either D(Pg) or S(Pn). 78 Partial Equilibrium Models: Per-unit taxes • Tax revenue is equal to uQ1, or area kfhn in Figure 2. • The economic incidence of the tax is split between the demanders and suppliers – Price demanders face goes up from P0 to Pg, which (in this case) is less than the statutory tax, u. 79 Partial Equilibrium Models: Taxes on suppliers vs. demanders • Incidence of a unit tax is independent of whether it is levied on consumers or producers. • If the tax were levied on producers, the supplier curve as perceived by consumers would shift upward. – This means that consumers perceive it is more expensive for the firms to provide any given quantity. • This is illustrated in Figure 3. 80 Figure 3 81 Partial Equilibrium Models: Elasticities • Incidence of a unit tax depends on the elasticities of supply and demand. • In general, the more elastic the demand curve, the less of the tax is borne by consumers, ceteris paribus. – Elasticities provide a measure of an economic agent’s ability to “escape” the tax. – The more elastic the demand, the easier it is for consumers to turn to other products when the price goes up. Thus, suppliers must bear more of tax. 82 Partial Equilibrium Models: Elasticities • Figures 4 and 5 illustrate two extreme cases. – Figure 4 shows a perfectly inelastic supply curve – Figure 5 shows a perfectly elastic supply curve • In the first case, the price consumers pay does not change. • In the second case, the price consumers pay increases by the full amount of the tax. 83 Figure 4 84 Figure 5 85 Partial Equilibrium Models: Ad-valorem Tax • An ad-valorem tax is a tax with a rate given in proportion to the price. • A good example is the sales tax. • Graphical analysis is fairly similar to the case we had before. • Instead of moving the demand curve down by the same absolute amount for each quantity, move it down by the same proportion. 86 Partial Equilibrium Models: Ad-valorem Tax • Figure 6 shows an ad-valorem tax levied on demanders. • As with the per-unit tax, the demand curve as perceived by suppliers has changed, and the same analysis is used to find equilibrium quantity and prices. 87 Figure 6 88 Partial Equilibrium Models: Ad-valorem Tax • The payroll tax, which pays for Social Security and Public Health Care, is an ad-valorem tax on a factor of production – labor. • Statutory incidence in the CR is split unevenly with a total of 34% paid by employer and 11% paid by employee. • The statutory distinction is irrelevant – the incidence is determined by the underlying elasticities of supply and demand. • Figure 7 shows the likely outcome on wages. 89 Figure 7 90 Tax Efficiency I. • Administrative Efficiency – costs of tax collection, salaries of financial officers, tax forms, time spent fulfilling forms, cost of tax advisors etc. – Direct costs – costs for the state – Indirect costs – costs for the taxpayers • Administratively Efficient Tax – low administrative costs and high revenue. 91 Tax Efficiency II. – Economic Efficiency –measures loss of benefits to consumers & producers – Excess Burden = Welfare Cost = Deadweight Loss (DWL) – Excess Burden (DWL) is a result of tax shifts: prices are distorted by the tax and economic subjects (people) are moved from their Pareto equilibrium and consequently their welfare is diminished by DWL 92 The magnitude of the excess burden of a unit tax Shaded area = Excess Burden, Deadweight Loss = DWL DWL = (Q0 – Q1)*Tax/2 Tax 93 The effect of demand elasticity on excess burden (optional) 94 The effect of tax rates on excess burden 95 Excess Burden Measurement • Implications of Figuers – Higher (compensated) elasticities lead to larger excess burden – Excess burden increases with the square of the tax rate – The greater the initial expenditure on the taxed commodity, the larger the excess burden 96 Excess Burden Review – Unit Tax 97 Excess Burden Review – Ad Valorem Tax 98