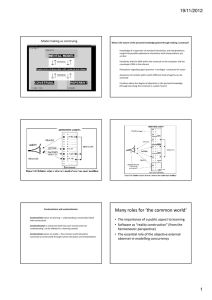

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46 (2010) 1126–1129 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Social Psychology j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / j e s p FlashReport Think and act globally, think and act locally: Cooperation depends on matching construal to action levels in social dilemmas☆ Lawrence J. Sanna a,b,⁎, Kristjen B. Lundberg a, Craig D. Parks c, Edward C. Chang d a Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, USA Department of Psychology, Washington State University, USA d Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, USA b c a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 31 January 2010 Revised 29 March 2010 Available online 25 June 2010 Keywords: Social dilemmas Cooperation Construal level Construal Level Theory (CLT) a b s t r a c t The authors proposed and tested hypotheses that cooperation in social dilemmas depends on matching construal to action levels. Using a computerized resource dilemma that modeled fishing the oceans, when motives were framed at abstract levels, in terms of values (e.g., cooperation vs. competition), high construal levels produced more cooperativeness and competitiveness, respectively. Conversely, when motives were framed at concrete levels, in terms of actions (e.g., returning vs. taking), low construal levels produced more cooperativeness and competitiveness, respectively. Implications for integrating and extending research on construal levels in social dilemmas and increasing cooperation are discussed. © 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. “Think globally, act locally”1 captures the idea that people should consider both global implications of what they do and specific actions for change. People could benefit society by conserving energy, recycling waste, contributing to public services, and refraining from overharvesting. The phrase also suggests actions can be construed in globally abstract or locally concrete terms. Conserving energy may be construed abstractly as “preserving the environment” or concretely as “turning off my lights,” while refraining from overharvesting may be construed abstractly as “being cooperative” or concretely as “not taking too many fish.” Guided by construal-level theory (CLT; Liberman, Sagristano, & Trope, 2002; Trope & Liberman, 2003), we hypothesized that cooperation in social dilemmas (Komorita & Parks, 1996; Messick & Brewer, 1983; Schroeder, 1995) depends on matching construal to action levels. For example, we predicted people will cooperate more when actions are conceived abstractly (“being cooperative”) and construal levels are high, ☆ We thank the anonymous reviewers and Better Decision Making (betterdecisionmaking.org) laboratory group members at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for comments on this article. ⁎ Corresponding author. Department of Psychology, CB# 3270 Davie Hall, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3270, USA. Fax: +1 919 962 2537. E-mail address: sanna@unc.edu (L.J. Sanna). 1 This phrase has disputed origins and been used not only to describe environmental concerns, but also those in other areas. Some argue it was first used by town-planner Patrick Geddes (1915), although the exact phrase does not appear in his book. Others argue it was first used in environmental contexts, variously, by social activists David Brower, Rene Dubos, and Buckminster Fuller, among others, who all may have used some form of the phrase at various times (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Think_Globally,_Act_ Locally). 0022-1031/$ – see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.018 but when actions are conceived concretely (“returning fish to a lake”) and construal levels are low. Thinking globally or locally thus results in more cooperation when construal and action levels correspond. Construal and Cooperation Social dilemmas are ubiquitous situations, from close relationships to international affairs, where collective- and self-interests conflict (Komorita & Parks, 1996; Messick & Brewer, 1983; Schroeder, 1995). A prototypical example is fishing the oceans. It may be profitable for individuals to maximize self-interests by harvesting all the fish they can. However, if other fishers did the same, the resource may become depleted, and all are worse off. Hardin (1968) called this “tragedy of the commons.” Many phenomena can be framed as social dilemmas, and increasing cooperation underlies many of society's most pressing concerns. Research suggests several ways construal levels may affect cooperation. CLT (Liberman et al., 2002; Trope & Liberman, 2003) proposes that people mentally represent actions in global, abstract, and superordinate form (high-level construals) or in specific, concrete, and subordinate form (low-level construals). Some research has shown that high construal levels led people to act in generally cooperative ways, for moral judgments (Agerström & Björklund, 2009), negotiations (Henderson, Trope, & Carnevale, 2006), and social dilemmas (Sanna, Chang, Parks, & Kennedy, 2009). For example, Henderson et al. found that high construal levels increased the likelihood of reaching integrative solutions when negotiating, and Sanna et al. found that high construal levels increased the likelihood of contributing to a common resource pool. L.J. Sanna et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46 (2010) 1126–1129 Construal levels may also interact with motives. Giacomantonio, De Drue, Shalvi, Sligte, and Leder (in press) found high construal levels led to mutually beneficial solutions on ultimatum and negotiation tasks when cooperative motives were active but to less mutual benefit when competitive motives were active, motives measured as individual differences (social values) or primed. High construal levels influenced whatever high-level motives (pro-social vs. pro-self) were active, resulting in more or less cooperation. Although not examining cooperation, other research suggests values have greater influences under high construal levels (Eyal, Liberman, & Trope, 2008; Eyal, Sagristano, Trope, Liberman, & Chaiken, 2009), irrespective of valence (virtue vs. vice). Matching Construal Levels We hypothesized that construal levels influence cooperation (competition) depending on matching construal to action levels, providing an integration and extension of existing findings. Giacomantonio et al. (in press) answer one side of the story by showing high-level pro-social versus pro-self motives led people to act cooperatively or competitively when construal level was also high. When construal level was low, highlevel motives did not affect behaviors. But we suggest there is more: The other side to the story is that low construal levels may also induce more cooperation or competition when motives are correspondingly framed at low levels. There are several reasons for these predictions. Empirically, although not examining cooperation, high-level values predict behavioral intentions for distant futures (abstract) while low-level actions predict intentions for proximal futures (concrete; Eyal et al., 2009; Torelli & Kaikati, 2009). High-level indirect versus low-level direct social influence strategies are used more in distant than near futures (Carter & Sanna, 2008). Abstract dispositions are used to explain distant future, but concrete factors to explain near future, behaviors (Nussbaum, Trope, & Liberman, 2003). Theoretically, matching matters because people develop generalized associations between construal and action levels (Liberman, Trope, McCrea, & Sherman, 2007), leading them to preferentially attend to features matching in levels of abstraction (Fujita, Eyal, Chaiken, Trope, & Liberman, 2008). For example, people pay more attention to persuasive arguments that match construal levels (Fujita et al., 2008). Extending this to cooperation (competition), people likewise may be influenced by high-level motives, abstract values, with high construal levels and low-level motives, concrete actions, with low construal levels. In sum, we predict when motives are framed abstractly (e.g., being cooperative vs. competitive), high construal levels will produce more cooperativeness and competitiveness, respectively, similar to Giacomantonio et al. (in press). In contrast, when motives are framed concretely (e.g., returning to vs. taking from a common resource pool), low construal levels will produce more cooperativeness and competitiveness, respectively. Method We assessed choices in a social dilemma analogue (Sanna, Parks, & Chang, 2003) after priming construal levels on an unrelated task (Freitas, Gollwitzer, & Trope, 2004), providing robust experimental controls. The experiment employed a 2 (Construal Level: High, Low)×2 (Motive Level: Abstract, Concrete)×2 (Motive Type: Pro-Social, Pro-Self) betweenparticipants design. Pro-social versus pro-self motives were framed abstractly (cooperate vs. compete) or concretely (return vs. take). Participants One-hundred forty-five psychology students participated for extra credit. 1127 Fishing Analogue Participants took the role of one of two fishers on a computerized task that modeled the fishing example in our Introduction; they were to make a profit without depleting the resource. They read that a lake was stocked with 100 fish, and profits would be confiscated if numbers fell below 70. On each trial (“season”), a participant caught 15 fish and decided how many to keep for profit and return to the lake. A table illustrated the consequences of this on each trial, using the equation (5 × n) − 30, where n was numbers of fish returned (e.g., returning 8 resulted in a 10-fish increase). Consequences were purportedly modeled on scientific data. To manipulate motives, participants in respective conditions read one of the following: Cooperate (abstract, pro-social): “As you perform this task, we ask that you consider being as cooperative as you can.” Compete (abstract, pro-self): “As you perform this task, we ask that you consider being as competitive as you can.” Return (concrete, pro-social): “As you perform this task, we ask that you consider the numbers of fish you should return to restock the lake.” Take (concrete, pro-self): “As you perform this task, we ask that you consider the numbers of fish you should take for profit.” The screen depicted a lake along with boxes having boat and fish icons labeled “keep fish” and “return fish,” respectively. Within seasons, a 15fish catch was displayed. Participants entered into the boxes how many fish they wanted to keep and return, which had to total 15. A tone signaled when responses were recorded. Another tone purportedly indicated the “other participant” responded; this second tone was rigged and there was no other participant. After tones, the following message always appeared: “There continue to be more than 70 fish in the lake.” Five seasons were played, but participants did not know this at the outset. Construal Level Priming Construal levels were primed on a purportedly unrelated health behaviors task before performing the fishing analogue. High-construal participants were primed by answering a series of “why” questions, and low-construal participants were primed by answering a series of “how” questions (Freitas et al., 2004). Presented by computer, the highconstrual manipulation had the statement “Why do I maintain good physical health?” at the screen top and “Maintain good physical health” at the bottom. Beginning at the bottom, these were connected by four vertically aligned boxes with upward facing arrows labeled why. Participants filled in the intermediate boxes successively, inducing a high-construal mindset. The low-construal manipulation had the statement “Maintain good physical health” at the screen top and “How do I maintain good physical health?” at the bottom. Beginning at the top, these were connected by four vertically aligned boxes with downward facing arrows labeled how, which participants filled in successively, inducing a low-construal mindset. Within both manipulations, participants' answers were made relative to their previous ones. Mood To assess whether construals operate independently of moods (Fujita, Trope, Liberman, & Levin-Sagi, 2006) we administered a series of items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) to all participants (happy, glad, joyful, and cheerful, and sad, miserable, gloomy, depressed). 1128 L.J. Sanna et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46 (2010) 1126–1129 Discussion Whether one chooses to cooperate (or compete) in social dilemmas depends on the match between construal levels and levels at which motives are construed. This extends and integrates prior research on construal levels and cooperative, mutually beneficial behaviors. One side of the story is that when motives are framed abstractly, in terms of values (e.g., cooperation vs. competition), high construal levels produce more cooperativeness and competitiveness, respectively, consistent with Giacomantonio et al. (in press). But the other side to the story is that when motives are framed concretely, in terms of specific actions (e.g., returning vs. taking), low construal levels produce more cooperativeness and competitiveness, respectively. Fig. 1. Mean numbers of fish returned (cooperation) by construal level, and motive level and type. Pro-social versus pro-self motives are represented either abstractly (cooperate vs. compete) or concretely (return vs. take). Results Data were analyzed using 2 × 2 × 2 analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with contrasts (Rosenthal, Rosnow, & Rubin, 2000) to compare means. Construal Manipulation Check Two judges unaware of hypotheses coded answers to the “why” and “how” prompts, following Fujita, Trope, et al. (2006). Statements superordinate to preceding ones were coded 1; those subordinate to preceding ones were coded −1. Statements fitting neither criterion were coded 0. Ratings were reliable (κ = .82) and averaged. There was only a construal level main effect, F(1, 137) = 128.40, p b .01, η2 = .49. As expected, statements of participants answering “why” questions (M = 1.49) reflected higher-level construals than those answering “how” questions (M = −1.31), supporting the manipulation's effectiveness. Numbers of Fish Returned (Cooperation) Numbers of fish returned indexed cooperation.2 Not surprising, was a motive-type main effect, F(1, 137) = 38.94, p b .01, η2 = .22, with pro-social participants (M = 30.21) returning more fish than pro-self ones (M = 21.20). More important was the predicted threeway interaction, F(1, 137) = 37.21, p b .01, η2 = .21 (Fig. 1). No other effects were significant. As predicted, participants were more cooperative in returning fish when abstract cooperative (M = 34.05) versus competitive (M = 17.66) motives were activated under high construal levels, t(137) = 5.61, p b .01, η2 = .18. Conversely, participants were more cooperative in returning fish when concrete return (M = 35.42) versus take (M = 16.16) motives were activated under low construal levels, t(137) = 6.78, p b .01, η2 = .25. The means in the remaining four conditions did not differ from each other (Ms = 25.55, 26.66, 25.83, 24.31, as ordered in Fig. 1). Mood Positive- and negative-mood ratings were unaffected by the independent variables or their interactions, all Fs b 1.0, suggesting results were independent of moods (Fujita, Trope, et al., 2006). 2 Because numbers of fish kept and returned had to sum to 15 on each trial, we report only numbers of fish returned. Results obtained when analyzing numbers of fish kept simply mirrors the results reported here. Further Implications and Research Construal levels were manipulated with a health behaviors task used in prior CLT research (Freitas et al., 2004) because it was unrelated in any obvious ways to our social dilemma, providing strong experimental control. However, an alternative that may be used by future research is to manipulate construal levels on variables directly relevant to social dilemmas. That is, construal levels can be influenced by several dimensions: time (later vs. now), social closeness (other vs. self), space (elsewhere vs. here), and reality (unreal vs. real; Fujita, 2008). For example, long- versus short-term concerns, feeling close to others, ingroups versus outgroups, and uncertainty have all been discussed by social dilemma researchers, and perhaps CLT may provide an integrative account of these variables. The motives we provided participants were very explicit. Empirically, they were unaffected by construal level priming, suggesting motives and construal levels were manipulated independently. Giacomantonio et al. (in press) obtained similar results when motives were primed or measured as social values. Participants did not spontaneously reconstrue the motives they were given (e.g., transform “returning fish” to “cooperation”). However, there may be times when (construal level) primed mind-sets carry over to subsequent tasks.3 Our prior research on construal levels in social dilemmas may provide evidence for this. When not given explicit motives, high construal levels led participants to focus cooperatively (a value) and low construal levels led them to focus concretely on taking the resource (a specific action; Sanna et al., 2009). Thus, priming construal levels appears to have simultaneously primed motive levels when no further explicit motives were provided. Although speculative, whether people sometimes reconstrue motives, or sometimes connect actions to values (Freitas, Clark, Kim, & Levy, 2009), could be interesting questions for future social dilemma research. We can consider other priming research. Bargh, Gollwitzer, Lee-Chai, Barndollar, and Trötschel (2001) found participants primed with synonyms for cooperation (e.g., helpful) cooperated in a resource dilemma. Our research differs by priming construal levels, not cooperation, and by providing explicit motives. Exploring ways of priming cooperation in future research could be valuable. Also interesting is prior CLT research mainly examines choice of strategies or goals after construal level priming. For example, after priming construal levels, Freitas et al. (2004) asked participants to choose which feedback they thought others would anticipate or select (e.g., liabilities-based vs. strengths-based). After priming (spatial) construal, Fujita, Henderson, Eng, Trope, and Liberman (2006) asked participants to choose between high- and lowlevel actions in forced-choice format, and coded choice of abstract or concrete language. It is possible, using procedures like Fujita, Henderson et al. (2006), that if people are asked instead to choose motive levels (e.g., cooperation vs. returning fish) one may find high- and low-level motives chosen under high- and low-construal levels, respectively. 3 We acknowledge an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this possibility. L.J. Sanna et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46 (2010) 1126–1129 Finally, increasing cooperation underlies many of society's most pressing concerns. Our research may have further implications for social dilemmas, such as when framing messages to produce environmentally responsible behaviors. People have generalized associations between construal and action levels (Liberman et al., 2007) producing functional matching whereby preferential attention is given to persuasive arguments that match construal levels (Fujita et al., 2008). This prior research does not examine cooperation or the levels at which motives are framed, as does ours. Nonetheless, it is possible that framing motives, like framing messages (Fujita et al., 2008), to match construal levels are each effective techniques to induce desired behaviors, and this is deserving of future research. Construal levels may also influence cooperation in other dilemmas, like Prisoner's or public goods dilemmas (Komorita & Parks, 1996; Messick & Brewer, 1983; Schroeder, 1995), and in other settings from close relationships to international affairs (Kelley et al., 2003; Parks & Sanna, 1999). In short, we hope our experiment helps spur further research into the theoretical and applied implications of CLT to explain and foster people's cooperative actions across a variety of settings. References Agerström, J., & Björklund, F. (2009). Moral concerns are greater for temporally distant events and are moderated by value strength. Social Cognition, 27, 261−282. Bargh, J. A., Gollwitzer, P. M., Lee-Chai, A., Barndollar, K., & Trötschel, R. (2001). The automated will: Nonconscious activation and pursuit of behavioral goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 1014−1027. Carter, S. E., & Sanna, L. J. (2008). It's not just what you say but when you say it: Selfpresentation and temporal construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1339−1345. Eyal, T., Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2008). Judging near and distant virtue and vice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1204−1209. Eyal, T., Sagristano, M. D., Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Chaiken, S. (2009). When values matter: Expressing values in behavioral intentions for the near vs. distant future. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 35−43. Freitas, A. L., Clark, S. L., Kim, J. Y., & Levy, S. L. (2009). Action-construal levels and perceived conflict among ongoing goals: Implications for positive affect. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 938−941. Freitas, A. L., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Trope, Y. (2004). The influence of abstract and concrete mindsets on anticipating and guiding others' self-regulatory efforts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 739−752. 1129 Fujita, K. (2008). Seeing the forest beyond the trees: A construal level approach to selfcontrol. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3, 1475−1496. Fujita, K., Eyal, T., Chaiken, S., Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2008). Influencing attitudes toward near and distant objects. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 562−572. Fujita, K., Henderson, M. D., Eng, J., Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2006). Spatial distance and mental construal of social events. Psychological Science, 17, 278−282. Fujita, K., Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Levin-Sagi, M. (2006). Construal levels and selfcontrol. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 351−367. Giacomantonio, M., De Dreu, C. K. W., Shalvi, S., Sligte, D., & Leder, S. (in press). Psychological distance boosts value-behavior correspondence in ultimatum bargaining and integrative negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Hardin, G. (1968). Tragedy of the commons. Science, 162, 1243−1248. Henderson, M. D., Trope, Y., & Carnevale, P. J. (2006). Negotiation from a near and distant time perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 712−729. Kelley, H. H., Holmes, J. G., Kerr, N. L., Reis, H. L., Rusbult, C. E., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2003). An atlas of interpersonal situations. New York: Cambridge University Press. Komorita, S. S., & Parks, C. D. (1996). Social dilemmas. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Liberman, N., Sagristano, M. D., & Trope, Y. (2002). The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 523−534. Liberman, N., Trope, Y., McCrea, S. M., & Sherman, S. J. (2007). The effect of level of construal on the temporal distance of activity enactment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 143−149. Messick, D. M., & Brewer, M. B. (1983). Solving social dilemmas: A review. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 11−44. Nussbaum, S., Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Creeping dispositionism: The temporal dynamics of behavior prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 485−497. Parks, C. D., & Sanna, L. J. (1999). Group performance and interaction. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R. L., & Rubin, D. B. (2000). Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research: A correlational approach. New York: Cambridge University Press. Sanna, L. J., Chang, E. C., Parks, C. D., & Kennedy, L. A. (2009). Construing collective concerns: Increasing cooperation by broadening construals in social dilemmas. Psychological Science, 20, 1319−1321. Sanna, L. J., Parks, C. D., & Chang, E. C. (2003). Mixed-motive conflict in social dilemmas: Mood as input to competitive and cooperative goals. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 7, 26−40. Schroeder, D. A. (Ed.). (1995). Social dilemmas. Westport, CT: Praeger. Torelli, C., & Kaikati, A. (2009). Values as predictors of judgments and behaviors: The role of abstract and concrete mindsets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 231−247. Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110, 403−421. Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063−1070.