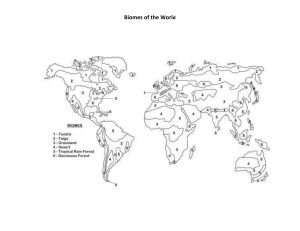

International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology ISSN: 1350-4509 (Print) 1745-2627 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsdw20 Community participation in the management of forest reserves in the Northern Region of Ghana Rikiatu Husseini, Stephen B. Kendie & Patrick Agbesinyale To cite this article: Rikiatu Husseini, Stephen B. Kendie & Patrick Agbesinyale (2016) Community participation in the management of forest reserves in the Northern Region of Ghana, International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 23:3, 245-256, DOI: 10.1080/13504509.2015.1112858 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2015.1112858 Published online: 22 Dec 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 780 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 7 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tsdw20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT & WORLD ECOLOGY, 2016 VOL. 23, NO. 3, 245–256 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2015.1112858 Community participation in the management of forest reserves in the Northern Region of Ghana Rikiatu Husseinia, Stephen B. Kendieb and Patrick Agbesinyaleb a Department of Forestry and Forest Resources Management, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana; bInstitute for Development Studies, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The 1994 forest and wildlife policy of Ghana provides the basis for community participation in forest management through participatory forest management. Even though forest reserves in the Northern Region are said to be managed collaboratively, fringe communities are supposedly involved only in maintenance activities of the reserve boundaries and seedling planting in plantation programmes. The forest reserves are said to be threatened by illegal activities from the fringe communities. This study therefore examined the nature of community participation in the management of forest reserves. It is a mixed method research in which structured interview schedule, in-depth interview and focus group discussion guides were used for data collection. Respondents comprised community members, forestry staff and NGOs. Communities’ participation was found to be passive and tokenistic and limited to boundary cleaning and providing labour on plantations. There is no formal collaboration between communities and Forest Services Division. Prospects to communities’ participation lie in the continuous flow of benefits and their active involvement in management decisions. Active involvement of communities in all decision-making processes, capacity building of communities and forestry staff, incentive schemes and awareness creation are recommended for promoting community participation in managing forest reserves in Northern Region. Received 29 August 2015 Accepted 19 October 2015 Introduction The relationship between humanity and forest can be said to be an interdependent one in that the continuous existence of the former depends upon the continuous production of resources and services by the latter. For the relationship to be sustainable, it must be a mutual one. Thus, our existence in an economical, quality and sustainable environment depends on how we harness and utilize the forest and other natural resources around (Jhingan 1997). If development is about change in the quality of living as affirmed by Kendie and Martens (2008), then the sustainability of that change will depend on how the drivers of that change are managed. Invariably, since individuals in society are the beneficiaries of natural resources, their rational actions, collectively or individually, may affect the sustainability of these resources. Also, because social actions are rationally motivated, individuals will make decisions about how they should act by comparing the cost and benefits of the different courses of action depending on how informed they are about conditions under which they are acting (Scott 2000a). As such, behaviour patterns will develop within societies that result from these actions. Similarly, if natural resource users CONTACT Rikiatu Husseini © 2015 Taylor & Francis rikihuss@yahoo.com KEYWORDS Community participation; forest reserves collaborative management; sustainability; Northern Region are informed about the constraints of their resources by involving them in management, they will be mindful of the means of acquiring them. Participation thus makes development plans more reflective of the needs of local people and makes them feel more connected in the development process (Kendie & Martens 2008). Forest reserves are perennially vegetated areas for either protective or productive functions (Ghana Forestry Department 1962). They provide reference sites for objective assessment of the sustainability of management practices (Walter & Holling 1990). In many African countries, forest reserves are sources of non-wood forest products which play a crucial role in the daily life and welfare of local people, as significant sources of food and fodder among others (FAO 1995). Timber is the fourth contributor to Ghana’s foreign exchange earnings (Marfo 2010). In the Northern Region of Ghana, forest reserves, abandoned farms and fallow lands form the major sources for shea nuts, a major economic crop for women (Blench 2006). Forest reserves in Ghana cover an area of 25,594 km2, spreading across the high forest in the south to the Savannah woodland in the north (FC 2003). There 246 R. HUSSEINI ET AL. are approximately 280 forest reserves in Ghana today, of which 214 are in the high-forest zone and 66 in the northern Savannah zone (Nsenkyire 1999). Of the 66 forest reserves, covering 880,600 ha in Northern Ghana, 24 (Djagbletey 2010) are in the Northern Region while 16 and 26 are in the Upper East and Upper West regions, respectively (Nsenkyire 1999). Over the years, the world’s forests have been under serious threat of deforestation. A Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO 2011) report indicated an alarming rate of deforestation with global loss of around 13 million hectares of forest yearly in the last decade (2000–2010). The report indicated that Africa has the second highest rate of deforestation worldwide at 3.4 million hectares annually. Ghana’s total forest cover which stood at 8.2 million hectares at the turn of the twentieth century has decreased to about 1.6 million hectares (Marfo 2010). The dwindling state of Ghana’s forest resources has been blamed on direct factors such as agriculture, urbanization, mining, illegal logging, population increase, forest fires and fuel–wood consumption (FAO 2001; Marfo 2010; Dartey 2014) while the underlying causes are reported to be related to lack of stakeholder participation in the formulation and implementation of forest policy, the nature of the policy itself, weak enforcement of existing legislation, government fiscal policies, and poverty (FAO 2001; Dartey 2014). These fundamental causes are what the 1994 forest and wildlife policy seeks to eliminate. An important guiding principle of the current policy is that it recognizes and confirms the importance of local people in pursuing all other guiding principles of the policy, and therefore proposes to place emphasis on the concept of participatory management and protection of forest and wildlife resources and to develop appropriate strategies, in consultation with relevant agencies, rural communities and individuals (FC 1994). Under the participatory management goals of the 1994 Forest policy fringe communities are expected to participate in decisionmaking for the productive management and protection of reserves through plantation development, establishment of firebreaks, cultivation of NWFPs, boundary maintenance and research programmes (Boakye & Baffoe 2010). Over the years several operations have been revised by the FC to help achieve equitable sharing of benefits and improved efficiency in management mainly in Southern Ghana through plantation development programmes and community livelihood initiatives (FC 2007). In spite of these efforts, there remain some challenges. In Southern Ghana, the roles of the community forest committees (CFCs) have been reduced to boundary maintenance and facilitation of social responsibility agreements with timber concessionaires. In essence, communities are providing labour rather than participating in management planning (Amanor 2003). Unfortunately, apart from the two wildlife protected areas selected for the Northern Savannah Biodiversity Conservation Programme (NSBCP), CFCs seem not to exist in the timber-poor Northern Region of Ghana. Meanwhile, per the 1994 forest policy, the Natural resources management project under the Forestry Development Master Plan for 1996–2020 had the Savanna Resource Management Project as a component designed to ensure re-establishment of local communities as primary clients of the Forest Services Division (FSD), and ensure equitable management of reserves in more efficient and socially sustainable ways (FC 2007). Yet, over 20 years after the adoption of the policy, the Savannah woodland reserves are still battling with encroachment and other illegal activities from the very people who are supposed to be helping in managing the reserves (Djagbletey 2010). Although forest reserves in the north are said to be managed collaboratively, the nature of communities’ involvement in management activities is not known. Therefore, the study was undertaken to (1) establish the stakeholders in the National Forest Plantation Programme in the Northern Region of Ghana; (2) determine the forest management practices in the reserves; (3) establish the nature of community participation in the management of forest reserves. Typologies and levels of community participation Typologies and indicators of community participation are devised depending on the nature of the activity and the responsibilities of the people involved. Among the popular ones are Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of participation and Pretty’s (1995) participation model. Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of participation (Figure 1) puts emphasizes on the extent to which citizens are empowered through participation. The outcome of her gradation is three main levels of ‘access to power’ with eight sub-levels or rungs: (1) non- participation, (2) tokenism and (3) citizen power. Pretty (1995) provided typologies of participation and characteristics in relation to conservation. His emphasis is on power and control. The outcome is seven types or rungs. These are as follows: (1) passive participation, (2) participation in information giving (3) consultation, (4) participation for material incentives, (5) functional participation, (6) interactive participation and (7) self-mobilization. Pretty (1995) INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT & WORLD ECOLOGY Figure 1. Ladder of participation. Source: Arnstein (1969). termed the first four rungs as levels of non-participation, rung 5 as low participation level and rungs 6 and 7 as full participation levels. Similar classification has been made by Johnston (1982). The study was thus guided by the typologies of participation by Pretty (1995), Johnston (1982) and Arnstein (1969) to assess the level and extent of community participation in the management of forest reserves. 247 theories (Donaldson & Preston 1995). Collective action is action by more than one person directed towards the achievement of a common good or the satisfaction of a common interest. Success in managing a collective good depends on how the groups are able to organize and govern their behaviour in solving commitment problems and monitoring individual compliance with sets of rules, which also depends on the rational choices made by the individuals in the group. Understanding the behaviour patterns of individuals in a community is thus a key to their ability to act collectively. The rational choice theory assumes that individuals will contribute to a collective action only if their individual expected benefits exceed their expected costs. Invariably, factors such as characteristics of the group or individuals, and the value each individual places on the resources by weighing the likely benefits and cost of their actions are key to achieving a common good. Understanding the interests and values of individuals in a group or society is therefore paramount to getting their support for collective action. Therefore, the study was also guided by the stakeholder theory by Donaldson and Preston (1995), which asserts that every legitimate person or group participating in the activities of a firm or an institution does so to obtain benefits but often the priority of the interests of all stakeholders is not obvious and therefore must be made apparent by involving them. Conceptual framework Theoretical framework This study is based on the collective action theory of common pool resources, (Ostrom 1990), the rational choice (Buchanan & Tullock 1962) and the stakeholder *S.H Interaction Stakeholders Forestry dept Community (all user groups and traditional authorities) NGOs Districts Ass EPA Collab.process Organizing Planning Implementing Monit.& Eval. The conceptual framework (Figure 2) is based on the concept of participation and the theoretical framework. The framework shows that sustainable management of forest reserves can be achieved through community participation. This can be initiated by the Outcomes of successful stakeholder interaction defined ownership & tenure rights, Benefits & Responsibilities. Interest analysis Capacity building (technical. & financial) Policy reform & legal framework (political will) Local needs & conditions, Respect for local authority & org. structures, Access to conflict res. mechanisms Knowledge acquisition improved capacity Institutional structures Access rules Forest protection Improved forest condition Sustained benefits Sustainable collaborative management of forest reserves Figure 2. A framework for community participation in collaborative management of forest reserves. Source: Based on a generalized collaborative process from Petheram et al. 2004. * = stakeholders’ interactive participation. 248 R. HUSSEINI ET AL. government through Forestry Department (FSD) or by the community through community leaders. It requires the involvement of all stakeholders in the collaborative processes through participatory methods in order to cater for concerns of all stakeholders and build the capacity needed for successful planning and implementation of management decisions. The essence is to empower FSD and community members through shared ownership, benefits and responsibility in restricting access and creating incentives for users to invest in the resource rather than over-exploit it. Outcomes of CFM depend on how the collective agreements are sensitive to local needs and conditions such as traditions, organizational structures and socio – cultural and economic activities, and how these affect the collaborative process and management decisions. Community participation in forest management will result in knowledge acquisition, build capacity of both parties to take initiatives that will improve resource management, increase flow of benefits to communities and ensure sustainable management of forest reserves (Figure 2). However, if the exclusionary system of management continuous where communities are deprived of ownership and tenure rights and alienated from processes that will espouse their interest in the resources, then the current situation will persist. The forestry officials will continue to regard communities as destroyers and dictate to them; and communities will continue to regard forestry officials as their enemies and flout their orders to meet their immediate needs. Consequently, the tragedy of the commons will set in despite CFM policy being in place. Table 1. Forest districts, sampled reserves and communities for the study. Forest districts Total no. of reserves Forest reserves per district selected Tamale 5 Walewale 5 Yendi 7 Damongo 5 Total 22 Water works F/R Sinsiblegbini NasiaTribitaries Gambaga scarp WB I Daka head water Kumbo Yakumbo Damongo scarp 8 Total no. of communities per reserve No. sampled (40% of total no.) 7 7 7 7 3 3 3 3 10 4 9 5 5 3 2 2 57 23 The total number of household heads in the 23 sampled communities was 14,343. Using table of sample size developed by Krejcie and Morgan (1970), a target population of 14,343 requires a sample size of 370 at 95% confidence level to ensure representativeness. Proportionate sampling was then used to sample household respondents for each community using the following formula: S1 ¼ P1=14; 343370; where P1 is the total number of households per community, 14,343 is the total population of households in the 23 communities, and 370 is the sample of households in the target population. This result is shown in Table 2. At the household level, the sampling frame consisted of the list of all households in the sampled communities obtained from the 2000 population and housing census report of the Ghana Statistical Research methodology This paper is based on a chapter of PhD thesis of the lead author. The study was conducted on the fringe communities surrounding forest reserves in four forest districts in the Northern Region of Ghana. It is a mixed method research design combing survey, in-depth interviews and focus group discussion. Owing to the fact that forest reserves in the region are managed by the same forest policies, practices and forestry agency, two reserves were randomly selected from each of the four forest districts. This resulted in the selection of eight forest reserves. Due to the variation in the number of communities near each reserve, proportionate sampling was used to get sample size of fringe communities per reserve. Due to resource constraint, 40% of the fringing communities were sampled from each reserve using the following formula: S1 ¼ 40=100P1 ; where P1 is the total number of communities per forest reserve and S1 is sample size of the fringe communities per reserve. This resulted in 23 communities (Table 1). Table 2. Sample size of households in selected communities. Selected Total no. of communities households Zogbele 5006 Yohini 2882 Choggu 36 Zibogu 26 Zakariyili 15 Tugu 98 Pigu 62 Sakpule 23 Pishigu 378 Samini 268 Gbani 122 Langbinsi 805 Nakunga 93 Kpatili 24 Nawuni 8 Gushiegu 1468 Kpatugri 32 Juanayili 93 Pusuga 152 Old Buipe 42 Lito 197 Damongo 2449 Soalepe 64 Total 14343 Proportion (40%) of the total household population 35.0 20.0 0.25 0.18 0.10 0.68 0.43 0.16 2.64 1.87 0.85 5.61 0.65 0.17 0.06 10.23 0.22 0.65 1.06 0.3 1.37 17.07 0.45 100 Source: Statistical Services (2011). Actual number of households sampled 130 74 1 1 0 3 2 0 10 7 3 20 2 1 0 38 1 2 4 1 5 63 2 370 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT & WORLD ECOLOGY 249 Table 3. Stakeholders in the National Forest Plantation Programme in Northern Region. Stakeholders District assembly Roles Assists to recruit labour through the assemblyman Interest Provides/create employment ECOTECH service Limited Contracted to Pre-finance the plantation prog. for FC Profit Community (farmers) Provide labour Increase food and cash crop production, income, sustained access to resource; sometimes for environmental benefits Increased food production Sustained access to the resources Traditional authorities Provides land (off-reserve) plantation or request for land for farmers if plantation is on-reserve Forestry commission Provides technical advice to (FSD) farmers; monitors the plantation Law-enforcing Prosecute offenders agencies (police) Reclaim degraded areas; increase stocking levels of trees; reduce pressure on the reserves Save resources from over exploitation and extinction Impact of interest on forest reserve Positive since it boosts farmers interest in the reserve Negative(once executed no interest in the development of the plantation crop) Positive but sometimes negative as it gives the room for activities that may kill the plantation Same as farmers. How can the impact be sustained or managed Increase financial support from the assembly Supervision & monitoring must be part of the contract Efficient supervision & monitoring; education on SFM; payment of realistic rates for labour provided Giving them some percentage of the proceeds from the plantation. Education on SFM Increase financial and logistics support Positive since it improves the resource condition (SFM) Positive as they ensure SFM Enforcement of laws on offenders in the management of forest reserves in their communities, while 48 (13%) respondents are of the opinion that FSD is the only stakeholder in charge of managing forest reserves (Table 4). The import of this result is that the implementation of the National Forest Plantation Programme (NFPP) in the study area did not follow any participatory process. This is because participatory resources management starts with analysis of stakeholders and their vested interests (Petheram et al. 2004; Carter & Gronow 2005). Therefore, if the implementation process was participatory, the respondents would have known the stakeholders involved. It also shows a conservatives’ instrumental approach to community participation, where participation is considered as a means to maintain the status quo of governmental officials (Fraser 2005). Table 4 shows the distribution of participants’ responses about their knowledge on the stakeholders in the management of forest reserves. A chi-square test of independence used to explore the association between the four forest districts on respondents’ views about stakeholders in CFM gave a p-value of 0.993 which is larger than the alpha value of 0.05. This implies that the difference in the responses from the four districts is not significant. The interviews with the regional and district forest managers showed stakeholders in the current plantation programmes in the study area to comprise: the Forestry Commission (represented by the FSD), district Service (Ghana Statistical Services 2000), because at the time results of 2010 population and housing census was not ready. Households in the sampled communities were numbered and the list generated was then subjected to a random sampling process to obtain the required number per community. Additionally, 87 key informants were selected. A total of 455 respondents were sampled for the study, the breakdown is presented in Table 3. Structured interview schedule was used for quantitative data (survey), while the qualitative data were obtained by in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The quantitative data were analysed using Statistical Product for Service Solution (SPSS) version 16 software. Descriptive statistics such as frequency tables, percentages, and cross-tabulation were used. Chi-square test was use to explore the association between forest districts. The results from the indepth interviews and the focused group discussions were categorized into appropriate themes and analysed through discourse analysis. Results and discussion Stakeholders in the National Forest Plantation Programme The study revealed that 280 (75.7%) of the 370 respondents do not know the stakeholders involved Table 4. Management activities involving community members. Distinct Damango Tamale Walewale Yendi Total Raising seedlings Plantation dev’t Boundary planting Fire control Boundary cleaning Total Freq% Freq% Freq% Freq% Freq% Freq% 8 0 10 5 23 (34.8%) (0.0%) (43.5%) (21.7%) (100%) 15 6 10 14 45 Source: Pearson ᵡ2 = 22.266; p-value = 0.035. (33.3%) (13.3%) (22.2%) (31.1%) (100%) 4 0 0 3 7 (57.1%) (0.0%) (0.0%) (42.9%) (100%) 24 15 15 15 69 (34.8%) (21.7%) (21.7%) (21.7%) (100%) 8 11 6 5 30 (26.7%) (36.7%) (20.0%) (16.7%) (100%) 59 32 41 42 174 (33.9%) (18.4%) (23.6%) (24.1%) (100%) 250 R. HUSSEINI ET AL. assembly (DA), Ecotech Services Ltd (a private company), farmers, chiefs, and law-enforcing agencies (police). It can be inferred from Table 3 that community is being represented by farmers while other user groups such as cattle herders, women’s groups, firewood and charcoal producers, hunters, and herbalists are not considered as stakeholders. Meanwhile, results from the focus group discussions revealed that activities of these user groups are directly dependent on the forest resources. Therefore, their exclusion could jeopardize the sustainability of the forest resources including the plantation crops. Their exclusion implies is that the heterogeneity of community was not considered during the plantation programme. As asserted by Eyben and Ladbury (1995), community consists of many groups of stakeholders differentiated by gender, occupation, access to resources, education, social characteristics and values. Accommodating the different values and interests within a community in broader event like the NFPP is thus a key for sustainability. Equally missing from Table 3 are other partners like NGOs and public institutions like Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) whose activities are related to forest resource management. This finding confirms Onencan’s (2002) findings where public sector agencies and NGOs were excluded in the management of Lendu forest in Uganda. NGOs are known to play a key role in ensuring transparency, decentralization and collaborative management (FAO 2004). The two programme officers of Evangelical Presbyterian Development and Relief Agency and WUNZALGU development association indicated that their activities with communities are mainly confined to providing tree seedlings, training on tree planting and advocacy on protecting economic trees on farms. These roles, although not directly related to activities in the forest reserves, have positive bearing on reducing the dependency of community members on the reserves. Their exclusion is therefore an indictment on the FSD since the FC considers them as stakeholders. Forest management practices in the reserves The study found the main management practices in the reserves to be forest protection and plantation development. Forest protection involves protection of reserves from fire and encroachment and external boundary cleaning and inspection. Plantation development according to the district managers is of twofold: the modified taungya plantation system (MTPS) and the National Forest Plantation Development Programme (NFPDP). Activities in the plantations include the following: weeding, site preparation, planting, pegging, and weeding around the plantation crop (under the taungya plantation). Crops allowed under the plantations were mainly annuals such as maize, millet, and groundnut. These differ from those allowed in the high-forest zones or Southern Ghana under the same programme where crops are mostly perennials such as plantain, cocoyam, and palm oil plants (Asare 2013). It was found that although forest districts are responsible for writing and updating all management plans, this has not been happening due to lack of funding. As such management activities have always been ad-hoc. This confirms Kalame et al. (2009) report that forest policies and practices in Burkina Faso and Ghana are mainly elements of risk management and not adjustment and improvement. Nature of community participation It was found that of the 370 household respondents, 196 (53%) indicated that their communities do not participate in the management of forest reserves while 174 (47%) admitted to community participation in the management of forest reserves. It was found that of the 370 household respondents, 196 (53%) indicated that their communities do not participate in the management of forest reserves while 174 (47%) admitted to the participation of their communities in the management of forest reserves. The common reasons given for nonparticipation of communities include: (1) members are not invited for any decision-making on forest reserves; (2) members are not involved because the forest reserves do not belong to them; (3) members are not involved because they are not workers of FSD; (4) members do not participate because they do not know the importance and benefits of the forest reserves. The reasons seem to imply that some respondents feel that their community members have been alienated from management of the forest reserves. This mindset is likely to hinder their commitment to efforts of collaborative management. Forty per cent (69) respondents of the 174 who admitted to the participation of their communities in forest management indicated fire control, plantation development, and boundary clearing as the main activities in which community members are involved. A chi-square test of independence used to determine relationship between the districts gave a p-value of 0.035, implying that there are significant differences in the opinions of respondents regarding what management activities community members are involved in. The difference in responses could be attributed to lack of interest of some community members in forest management activities as a general effect of their INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT & WORLD ECOLOGY alienation. Table 4 shows that the management activities communities are involved in. Views from the forestry staff The household responses were confirmed by the district forestry staff who revealed that currently the major collaborative management project involving community members in the study area is the NFPDP. The forestry staff revealed that in both MTPS and the NFPDP, community participation has always been confined to plantation establishment, external boundary cleaning and planting, and voluntary fire control. It was found that there was no participatory planning and negotiations with community members prior to the starting of the plantation activities. Community members were simply recruited as labourers by DAs, since the major aim of the programme was to create jobs for communities. The district managers revealed that even though the FSD is the main implementing body for the government, they were not part of the planning and designing of the NFPDP programme as they got informed about its start through circulars from the national head office. According to the managers, similar complaints were made by the district chief executives (DCEs) which led to apathy on the part of some DAs. As a result, some DAs did not see it as their responsibility to negotiate for land from the traditional leaders. District managers had to take up the task of negotiation for lands which made their work difficult. Clearly these results infer that the process of involving communities in forest management activities was top– down. Stakeholder involvement did not follow the initial participatory processes that characterize collaborative management. Collaborative management involves all partners’ right from planning, through to implementation and continuous review and improvement of the planned activities (Petheram et al. 2004). The prevailing method of involving communities can be equated to the conformist and contributions approach to community participation where decision-making is top–down (Fraser 2005). The result partly confirms Ahenkan and Boon’s (2010) observation that Ghana’s forest policy is only theoretical with attitude of forest officers being the same as the implementation of previous policies. However, the blame cannot be put totally on the forestry officers because from their responses, FC, the highest body responsible for regulating activities in the sector did not create the room for proper co-ordination and collaborative process to take place. These results show that even in the sight of the current policy, forest administration in the Northern Region of Ghana is still top–down. Views from assembly members on nature of participation For the assembly members’ sub-sample, 18 out 21 assembly members interviewed disclosed they only 251 share information and educate community members about fire control since their role as assembly members is to help in the development of their communities. They advise community members against illegal cutting of trees and the prevention of bush fires. The remaining six assembly members (Gushiegu, Kpatugri, Juanayili, Pusuga, Saamini and Zogbele) indicated that they are usually called upon during the plantation programmes to help in organizing community members. When asked about the role of the DA in the management of the forest reserves, 18 assembly members either did not have any idea on how their DA is involved or said their DAs are not directly involved in the management of forest reserves. Views from traditional leaders Although the role of traditional leaders in forests management according to FC (2007) is to seek genuine interests of citizens to promote improved standards of living and to offer leadership to achieve set goals of society, the interviews with the chiefs showed divergent views on the participation of their community members in forest activities. Thirteen out of the 23 chiefs indicated that their communities do not participate in the management of forest reserves, while the remaining 10 answered in the affirmative. The common reason given by the 13 chiefs who answered in the negative is that their community members are not involved because they are not workers of FSD. The responses of the chiefs confirm the views of the majority of household respondents that community members are not involved in management of forest reserves. This is because even the 10 chiefs who admitted to the participation of their communities said so, in reference to boundary clearing, fire control and plantation programmes, implying that they are not involved in the decision-making process. This kind of participation is similar to tokenism or passive participation (Arnstein 1969; Pretty 1995). Second, the divergent views from the chiefs affirm the views from the district forest managers that there were no proper stakeholder meetings prior to the commencement of the plantation programme in the study area. This is probably the reason for the thinking of some chiefs that one needed to be a staff of FSD to be concerned about the forest resources. That inadequate participation does not lead to success is pointed out clearly by Petheram et al. (2004). According to authors, success in collaborative management is linked to the processes of pre-negotiation and meetings among stakeholders. Views from women leaders ‘Magazia’ (s) is the name given to community women leaders in the study area. As the name suggests they 252 R. HUSSEINI ET AL. are the mouth-piece of women and prevail over matters concerning women in development. Among the principles of CFM is the involvement of all interest groups in all decision-making processes (Scott 2000b). Participation of women in forest management is thus an issue of concern since they are the primary users of non-timber forest products such as firewood, vegetables, and fruits from the reserves. Out of the 23 magazias interviewed, only the Gusheigu magazia admitted to her involvement in the management of forest reserves. She disclosed her role as reporting illegal activities to the forest guards. The other 22 magazias admitted that they had no involvement in forest management activities. However, most of them indicated that they sometimes help in fire control (voluntary), preparation of food for their husbands during tree planting, and advice women against cutting fresh-wood for fuel–wood. Some said that they were not involved because by their tradition, women are not supposed to be involved in forest activities. As women leaders, they all disclosed that their role is to seek for the welfare of women in their communities which is mainly centred on naming and wedding ceremonies, funeral rites and organizing for credit and loan facilities for women. The following are expressions of the magazia of Kpatile community: I play the role of a spoke’s person for the women and organize them for general issues. I’m not involved in the management of the FR because I have never been invited by the FSD. This finding confirms the over silence on the needs of women and their representation in forest management committees as observed in the case studies reviewed on CFM. This is a clear case of social exclusion where individuals or groups are wholly or partially excluded from participation in the society within which they live (Rawal 2008). It is probably as a result of the culture of the people which is further aggravated by lack of institutional structures on the part of government for promoting social inclusion. As revealed by the UNDP report on human development (2007), the customary preference for male leadership and control of resources have placed men ahead of women in most Ghanaian societies. These gender differences have become a major source of exclusion for women especially in some parts of the Northern Ghana. This is evident by their lack of visibility in the public domain though they may not be excluded in economic activities in general. Thus, confirming the alienation of women in forest activities. Similar responses were obtained from the focus group discussions. It was also found that out of the 174 household heads who admitted to the participation of their communities in forest activities, 82.8% (144) revealed that communities only participate at the implementation of activities especially during the plantation development programmes. The common reasons given by the 144 (82.8%) respondents are that they are not invited for any management activity apart from boundary cleaning and plantation work. Using the ladder of participation, the participation of fringe communities could be described as tokenistic or participation for material incentives (Arnstein 1969; Pretty 1995). The pattern of involving communities is still top–down and is likely to thwart the outcomes of any collaborative management efforts in the area. Furthermore, the perceptions of household heads about the roles performed by their community members were studied in relation to Pretty’s (1995) participation model to determine their level of participation. Figure 3 indicates the frequency and percentage of household heads, and the corresponding roles they perceived describe best the type and level of their community’s participation and control over the collaborative process. Figure 3 shows that majority 120 (69%) of the 174 household heads who admitted to the participation of their community members in forest activities, described their participation as passive because they are always told what to do mainly at the implementation level. Relating these findings to the various levels of participation described by Arnstein (1969), Johnston (1982) and Pretty 1995) shows that fringe communities’ level of participation in the management of forest reserves range from non-participation to tokenism (Figure 3). Based on this result, it suffices to say that the approach to management of forest reserves in the region is top–down disguised in the face of collaborative forest management. Communities collaborate in resource management for two main objectives: benefit-sharing or powersharing depending on the role played or the position of community members (Wily 2002). The study found that of the 370 respondents, 203 (54.9%) of them indicated there is no collaboration between their community and the FSD. Twenty-seven per cent (100) respondents disclosed that their collaboration is for access to resources only. Similarly, with the exception of Langbinsi assemblyman and Saamini women’s leader, all the chiefs, assembly members and magazias revealed that there is no formal collaboration between their communities and the FSD. The assembly members disclosed that they only serve as contact persons and middle men between the FSD and farmers during plantation programmes and when there is dispute between the staff of FSD and community members. The Langbinsi assemblyman made it known that although he is aware of the need for collaboration between him and the FSD, there is currently no such agreement. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT & WORLD ECOLOGY Typology Roles of community Frequency/ Level of Level of members in the NFPP Percentage participation power & Self mobilization Taking initiative 0 (0) Interactive Joint analysis of problems 253 control High independent of FSD High level 0 (0) participation and implementation of action plans between community and FSD Functional Forming groups to meet 0 (0) predetermined goal of Mid- level FSD Participation for material incentive Participation consultation Participation Community provides labour in return for cash & land for farming participation 48 (27.6) Tokenism by FSD consult community and listen to their views on predefined projects 0 (0) in Community answer questions from FSD without the opportunity to influence proceedings of the project 6 (3.4) information giving Passive participation Community being told what to do or has happened by the FSD 120 (69) Non LOW participation NON Figure 3. Typologies and levels of community participation in the management of forest reserves. Source: Pretty (1995), Johnston (1982) and Arnstein (1969). The Saamini ‘magazia’ disclosed her collaboration with FSD as a caretaker for planting materials during tree planting activities. The district forest managers, however, maintained that FSD’s collaboration with communities is for ‘management and benefit sharing’. They argued that although there is no formal agreement, there is collaboration because by providing labour community members get employment benefits and help in managing the reserves. Comparing the survey result to Wily’s (2002) paradigms of CFM puts the communities under the broad category of collaboration for benefit sharing where the community is either a beneficiary, user, or rule follower. By Wily’s distinctions, the results imply that the objective for management by FSD is to gain communities cooperation by allowing them some restricted access to the resource in exchange for labour wages and not to delegate power to them. To be sustainable, communities have to collaborate as actors, or managers or rule makers (power sharing) (Wily 2002). More so, over 98% (363) of respondents admitted that their communities do not have any forest committees (CFCs). This was confirmed by the district forest managers who attributed the absence of CFCs to the lack of timber resources in the Northern Region of Ghana which serve as a disincentive for the people at the top management to spend resources in constituting CFCs. These results confirm the reports by Amanor (2003), Petheram et al. (2004), Carter and Gronow (2005), and Odera (2009) that Ghana’s collaborative management is merely consultation and provision of labour with some level of benefit sharing without ownership and responsibility. Community participation is not fully satisfied by just receiving people’s contributions in the form of kind or cash. Participation must contain elements of initiative and decision, emanating from the community itself and when community contributions do not comprise such bottom–up elements, the concept changes from participation to recruitment Nasikum (1990). This lack of participation, according to Kumar (2002), does not instil a sense of ownership in the people. Conclusion and recommendations Following a critical review of the findings, the study is concluded as follows: 254 R. HUSSEINI ET AL. Participation of forest fringe communities in the management of forest reserves ranges from passive to tokenism, meaning that fringe communities have no control over access to resources and management. This situation is an incentive for unsustainable resource management and poverty. Communities will resist exclusion by resulting to illegal ways to meet their needs. Communities collaborating informally as labour providers imply that they have no rights to decisionmaking processes; cannot take initiatives to manage forest resources; and are denied the opportunity to develop their ability to evolve initiatives to improve their livelihoods and sustain forest resources for the future. The absence of CFCs means that there are no local structures for collaborating with communities, thereby helping FSD to maintain their status quo. The FC should institute sub-CFM units at the district level to serve as liaison between FSD and communities for the synthesis and advancement of FDS’s development agenda and interests of local communities. The collaborative forest management unit (CFMU) of FC should help the FSD in the region to constitute CFCs to serve as local structures for collaborative management. Since plantation development is currently the only project involving communities, it should be sustained by a formal agreement between communities, Das, and FSD on the modality of involving communities and sharing of benefits. Geolocation Recommendations To ensure effective community participation in the management of forest reserves in the Northern Region, we recommend the following concept: FSD should initiate a formal collaborative agreement with all the user groups: chiefs, assembly persons, farmers, herbalist, women groups, hunters, cattle herders, charcoal, and firewood producers, through an organized participatory assessment of viability and needs for CFM in planning and implementation of management decisions. Northern Region is located between latitude 8 30′ and 10 30′ N and lies completely in the savannah belt. It has Togo and La Cote D’Ivoire to the East and West, respectively, as its international neighbours. To the south, the region shares boundaries with Brong Ahafo and the Volta Regions, and to the north it shares borders with the Upper East and Upper West regions. The provisional results of 2010 population and housing census gave the regional population as 2,468,557 at a growth rate of 2.9. Figure 4 shows the regional map with the forest districts and political boundaries. Figure 4. Political and forest districts in the Northern Region of Ghana. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT & WORLD ECOLOGY Disclosure statement No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. References Ahenkan A, Boon E. 2010. Assessing the impact of forest policies and strategies on promoting the development of non-timber forest products in Ghana. Kamla-Raj 2010 J Biodiversity. 1:85–102. Amanor KS. 2003. Natural and cultural assets and participatory forest management in West Africa. In: Conference paper series No. 8. International conference on natural assets; Jan 8–11; Tagaytay. Political Economy Research Institute and Center for Science and the Environment. p. 35. Arnstein SR. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann. 35:216–224. Asare A. 2013. Head, collaborative forest management unit. Research Management Support Centre, FC. Kumasi. Personal communication. 2012 Mar 3. Blench RM. 2006. Dagbani plant names. Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom. Preliminary circulation draft. Boakye KA, Baffoe KA 2010. Trends in forest ownership, forest resource tenure and institutional arrangements: case study from Ghana; p. 23. Retrieved on 10/10/2011 www.fao.org/forestry/12505.01d Buchanan JM, Tullock G. 1962. The calculus of consent. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. Carter J, Gronow J. 2005. Recent experience in collaborative management. A Review Paper. Published by Center for International Forestry Research; p. 57. Dartey SA 2014. 100 Years of forestry in Ghana. First national forestry conference. Kumasi: CSIR- Forestry research institute of Ghana. September 16–18. Djagbletey ED. 2010. Personal Communication on situational report on forest reserves. Tamale: Northern Regional Forest Manager. Donaldson T, Preston L. 1995. The stakeholder theory of the modern corporation: concepts, evidence and implications. Acad Manag Rev. 20:65–91. Eyben R, Ladbury S. 1995. Popular participation in aidassisted projects: Why more theory than practice. In: Nelson N, Wright S, editors. Power and participatory development. London: Intermediate Technology; p. 192–200. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2011. World deforestation decreases, but remains alarming in many countries. Global forest resources assessment 2010.FAO Media Centre. Rome [updated 2010 Mar 25; cited 2011 Jan 21]. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 1995 Jan 17–27. Report of the International Expert Consultation on NonWood Forest Products. Yogyakarta: Hosted by the Ministry of Forestry, Government of Indonesia. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2001. State of the world’s forests 2001. Rome: FAO of the United Nations; p. 181. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2004. Enhancing cooperation and promoting regional agreements on forests in Africa. African forestry and wildlife commission. Fourteenth session. 18–21 Feb. Accra, Ghana. Forestry Commission of Ghana. 1994. Forest and Wildlife Policy, Accra: Forestry Commission; pp. 1–7. 255 Forestry Commission of Ghana. 2003. Ghana forestry commission at a glance: Forest services division (FSD) – background of forestry in Ghana; pp. 1–26 Forestry Commission of Ghana. 2007. Forestry sector programmes: Savannah resources management project. Fraser H. 2005 July. Four different approaches to community participation. Community Dev J. 40:286–300. Ghana Forestry Department (FD). 1962. Annual report. Accra. Ghana Statistical Services. 2000. Extract from the report of the 2000 population and housing census. Northern Region, Tamale. Jhingan ML. 1997. Macroeconomic theory. 4th ed. Delhi: Vrinda. Johnston M. 1982. The labyrinth of community participation: Indonesia’s experience. Community Dev J. 7:3. Kalame FB, Nkem J, Idinoba M, Kanninen M. 2009. Matching national forest policies and management practices for climate change adaptation in Burkina Faso and Ghana: mitigation and adaptation strategies for global change. Volume 14. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Amsterdam: Springer. Kendie SB, Martens P, editors. 2008. Governance and sustainable development – an overview. In Governance and sustainable development. Cape Coast: Marcel Hughes Publicity Group. CDS UCC; p. 1–15. Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 30:607–610. Kumar S. 2002. Methods for community participation: a complete guide for practitioners. London: ITDG Publishers. Marfo E. 2010. Chainsaw milling in Ghana: context, drivers and impacts. Wageningen, the Netherlands: Tropenbos International; p. 2. Nasikum. 1990. Percikan pemikiran FISIPOL UGM tentang Pembangunan. Yogyakarta: FISIFOL UGM. Nsenkyire EO. 1999. Forestry Department’s strategies for sustainable Savannah woodland management; p. 11. Odera JA. 2009. Changing forest management paradigm in Africa: a case for community based forest management systems. Research programme of sustainable use of dry land biodiversity (RPSUD). Discov Innov. 21:35. Onencan WK. 2002. Protectionism, natural resource conservation policy and patterns of household poverty: a case study of Lendu forest and surrounding communities in Nebbi District. In: Working paper series of Network of Ugandan Researchers and Research Users No. 29. Kampala: NURRU publications. Ostrom E. 1990. Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Petheram J, Stephen P, Gilmour D. 2004. Collaborative forest management: a review. Australian Forestry. 67:137–146. Pretty JN. 1995. Regenerating agriculture: policies and practice for sustainability and self reliance. Washington: National Academy Press. Rawal N. 2008. Social inclusion and exclusion: a review. Dhaulagiri J Sociol Anthropol. 2:161–180. Scott J. 2000a. Rational choice theory. In: Browning G, Halcli A, Webster F, editors. From understanding contemporary society: theories of the present. London: Sage; p. 13. Scott P. 2000b. Collaborative forest management – the process. A paper at the National Workshop on Community Forestry. Kampala, Uganda. 256 R. HUSSEINI ET AL. Statistical Service of Ghana. 2011. Northern Region. Tamale. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2007. The Ghana Human Development Report: towards a more inclusive society. Walter CJ, Holling CS. 1990. Large-scale management experiments and learning by doing. Ecology. 71:2060–2068. [cited 2011 July 10]. Available from: www.mass.gov.envir/ forest/pdf/whatare_forestreserves.pdf Wily LA. 2002. Participatory forest management in the United Republic of Tanzania. Presentation at the second International workshop on participatory forestry Africa, 18–22 Feb. Arusha, Tanzania.