Т. Л. Barabash

A Guide

to

Better

Grammar

(Пособие no грамматике

современного английского

языка)

ИЗДАТЕЛЬСТВО «МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫЕ ОТНОШЕНИЯ»

Москва ‘1975

4И (Англ.)

Б 24

Барабаш Т. А.

Б 24

Пособие по грамматике современного английского

языка (A Guide to Better Grammar). M., Междунар.

отношени я», 1975.

288

Пособие предназначено для лиц, владеющих основами английского языка

и желающих усовершенствовать свои знания. Цель пособия — помочь учащимся

выработать навыки грамматически правильной английской речи.

Б 70104—008 48_75

ф Издательство «Международные отношения», 1975 г.

4И (Англ.)

ОТ

АВТОРА

Данное пособие предназначено для лиц, совершенствующихся в

изучении английского языка на курсах или путем самостоятельной

работы, а также для студентов языковых вузов переводческого про­

филя и гуманитарных факультетов университетов. Оно предполагает

владение элементарной грамматикой и лексикой в объеме первого курса

языкового вуза.

Пособие является в своей основе нормативным. Его цель — позна­

комить изучающих английский язык с системой грамматических пра­

вил современного английского языка, с тем чтобы способствовать

улучшению навыков грамматически правильной устной и письменной

речи.

Исходя из практических целей пособия, автор предлагает такую

трактовку грамматических явлений, которая представляется наиболее

приемлемой для достижения этих целей.

Не претендуя на исчерпывающую полноту описания всей системы

грамматического строя современного английского языка, пособие

охватывает лишь узловые темы, представляющие значительные труд

*

ности для изучающих язык.

В пособии отсутствует ряд тем, имеющихся в большинстве курсов

нормативной грамматики; этот материал рассматривается в совокуп­

ности с другими вопросами. Так, например, в разделе “Parts of Speech’’

подробно освещаются лишь такие части речи^ как существительное,

артикль, прилагательное, наречие, местоимение и глагол. Особенности

употребления других частей речи затрагиваются попутно в соответ­

ствующих главах пособия. Например, особенности употребления чис­

лительных в составе словосочетаний рассматриваются в главах об

артиклях, прилагательных, а также о членах предложения; особеннос­

ти употребления союзов и предлогов — как в разделе о частях речи,

так и в разделе о структуре предложения; роль модальных слов, час­

тиц и междометий — в разных главах обоих разделов. В разделе

“Sentence Structure” нет специальной главы, посвященной порядку

слов, поскольку он рассматривается как неотъемлемый компонент

структуры предложения и занимает значительное место в главах, пос­

вященных главным и второстепенным членам предложения.

В основу трактовки большинства тем легла концепция, наложен­

ная в «Грамматике английского языка» Л. С. Бархударова и

Д. А. Штелинга.

При описании грамматических явлений, их форм и функций автор

стремился представить наиболее современную норму употребления,

предлагаемую в английских и американских учебниках грамматики

последних лет издания, с особым упором на профилактику возможных

ошибок, возникающих вследствие интерференции русского языка.

8

В пособии дается стилистическая оценка грамматических явлений,

с тем чтобы способствовать правильной ориентации в области граммати­

ческой синонимии. Кроме того, там где это необходимо, проводится

сопоставление с русским языком что должно помочь выявлению зако­

номерных грамматических соответствий, используемых при переводе.

Большинство иллюстративных примеров взято из современной

английской и американской литературы, периодики, киносценариев,

а также из словарей, лингафонных курсов и курсов грамматики, из­

данных в Англии и США. Часть примеров заимствована из ранее из­

данных в Советском Союзе учебников грамматики.

Практическая часть пособия (“Exercises”) состоит из упражнений

по каждой из тем. Упражнения разработаны с учетом типизированных

трудностей проходимого материала и предназначены, в частности, для

предотвращения наиболее типичных ошибок русских учащихся.

Основные виды упражнений: анализ формы, функции и значения,

реконструкция, трансформация, перевод с английского языка на рус­

ский и с русского на английский. Характер упражнений определяется

как общими целями пособия, так и спецификой каждой конкретной

темы.

Упражнения составлены на основе современных оригинальных

источников. Упражнения типа '‘Translate into English”, имеющие

целью контроль усвоения грамматического материала, предусматри­

вают употребление лексики, доступной учащимся, на которых рассчи­

тано данное пособие.

К пособию прилагается словарь-индекс грамматических терминов

(на указанных в нем страницах впервые упоминаются или раскрываются

значения соответствующих терминов).

Библиографический список включает только те книги, которые

были использованы при написании данного пособия.

Автор выражает глубокую признательность доктору филологичес­

ких наук, профессору Л. С. Бархударову за ценные критические заме­

чания, которые были учтены при подготовке рукописи пособия к

печати.

CONTENTS

Introduction.............................................................

Part I:

7

Parts of Speech

Nouns

.........................................................................

Articles.............................................................................

Adjectives........................................................................

Adverbs

.........................................................................

Pronouns.........................................................................

Verbs...................................................................-.

Tense and Aspect.......................................

Voice.............................................................

Mood.............................................................

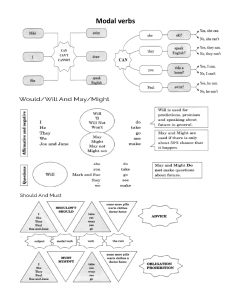

Modal Verbs.......................................................

Verbals.............................................................................

The Infinitive..................................................

The Gerund .................................................

The Participle............................................

13.

21

31.

3?

40

64

69

87

93

105

121

122

130

140

Part II: Sentence Structure

Simple Sentences.......................................................

Principal Partsof the Sentence ...

Secondary Partsof the Sentence ...

Composite Sentences

.............................

Reported Speech.......................................................

150

161

176

192

208

Part III: Exercises

Nouns............................................................

. .

Articles........................................................................

Adjectives and Adverbs

Pronouns...................................................................

Verbs.........................................................................

Tense and Aspect............................ <. . . .

Voice.................................

219

220

226

227

229

230

235

6

Mood

..............................................................................

Modal Verbs .

......................................................

The Infinitive............................................................

The Gerund..................................................................

The Participle

......................................................

Simple Sentences......................................................

Principal Parts of the Sentence..............................

Secondary Parts of the Sentence..............................

Composite Sentences......................................................

Reported Speech

......................................................

24^

244

248

251

256

259

262

268

274

Grammatical Terms (Glossary and Index) . .

Bibliography ..............................

.....

281

288

INTRODUCTION

§ 1. Language is realized through speech, i. e. linguistic

intercourse between two or more people. It is exercised by means

of connected communications, chiefly in the form of sentences.

All words in a sentence are grammatically connected. It

means that they are modified and joined together to express

thoughts and feelings.

The main object of grammar as a science is the grammatical

structure of the language, i. e/ the system of laws governing

the change of grammatical forms of words and the building

of sentences.

The aim of this grammar review is to give up-to-date rules

which must be obeyed if one wants to speak and write the lan­

guage correctly.

§ 2. The main difference between the grammatical structure

of English and that of Russian lies in ways of expressing gram­

matical relations between words in word-groups and sentences.

In Russian these relations are expressed by inflexions: заглавие

книги. In English they are mainly expressed by word-order

and structural words: the title of the book.

The former type of grammatical structure is called synthet­

ical while the latter is called analytical.

Thus Modern English is an analytical language, though it

has some survivals of the synthetical structure. These are ex­

pressed in a number of inflexions.

§ 3. Grammatical forms of words can be changed In differ­

ent ways.

By grammatical forms we understand variants of a word

having the same lexical meaning but differing grammatically:

book — books.

There are the following four ways of changing grammatical

forms of words in English: (1) the use of suffixes; (2) the use

7

of sound change; (3) the use of suppletive forms; (4) the use of

analytical forms.

Suffixes are form-changing elements added to the root of

a word; they arc also called inflexions. These are the following:

-e(s)

the plural of nouns

the possessive of nouns

the third person singular of the Present Indefinite Tense

the Past Indefinite of the Indicative Mood

-(e)d the Subjunctive Mood

participle II

-•ng 1 participle I

gerund

-er, -est the comparative and superlative degrees of adjectives

and adverbs

Sound change is the use of different root sounds in different

grammatical forms of a word. These interchanging sounds can

be either vowels (speak — spoke) or consonants (wife —

wives).

Note that sound change can be combined with the use of inflex

ions (child — children, wolf — wolves).

Suppletive forms are grammatical forms of a word coming

from different roots. These are: be — am — is — was, go —

went, I — me, good — better, bad — worse.

Analytical forms are made up of two components, auxiliary

and notional. An auxiliary expresses no lexical meaning of its

own, but changes grammatically. A notional word is used as an

unchanged element and carries a lexical meaning.

Analytical forms are widely used in forming the tense,

voice and mood of the verb, etc.

I

\ written a letter.

He has J

N • t e that out of the four ways of changing grammatical forms

found in Modern English, only two are productive, namely the use of

suffixes and the use of analytical forms.

i 4. The general meaning of two or more grammatical forms

opposed to each other makes up a grammatical category. Com­

pare: student — students, booh -* books.

8

The forms student and book denote singularity, while the

forms students and books denote plurality. The forms of these

two columns when opposed to each other, have one general mean­

ing, that of number. Thus the oppositions of grammatical

forms expressing the grammatical meaning of number makes

up the grammatical category of number.

The noun has the grammatical categories of number and case.

The verb has the grammatical categories of person, number,

tense, aspect, voice and mood. Adjectives and adverbs express

degrees of comparison. Some pronouns express the categories

of person, number, gender, case and degrees of comparison.

The system of grammatical forms of a word is called a para­

digm.

§ 5. According to their lexical meaning, morphological

characteristics, syntactical functions and types of word-groups

they form all words fall into certain classes called parts of

speech. There are twelve parts of speech in Modern English: (1)

nouns; (2) adjectives; (3) pronouns; (4) numerals; (5) verbs;

(6) adverbs; (7) prepositions; (8) conjunctions; (9) articles;

(10) particles; (11) parenthetical words; (12) interjections.

All parts of speech are subdivided into notional and structur­

al words.

Notional words have a full lexical meaning of their own,

i. e. they denote things, their qualities, actions, states and cir­

cumstances. They can function as independent parts of the sen­

tence, i. e. as subject, predicate, object, attribute or adverbial

modifier.

Structural words have no lexical meaning of their own and

cannot be used as independent parts of the sentence. They are

subdivided into connectors and determiners.

Connectors are used to connect words grammatically or shape

the grammatical forms of a certain part of a sentence. Here be­

long prepositions, conjunctions, modal, auxiliary and linking

verbs.

Determiners are used to specify the meaning of the notional

words they refer to. These are articles, particles and some pro­

nouns.

However, the border-line between structural and notional

words is not quite definite. Sometimes it passes between parts

of speech (nouns and articles), sometimes it is drawn inside a

part of speech (notional and auxiliary verbs). One and the same

word may be used as either notional or structural in different

contexts.

9

§ 6. All words in speech are grammatically connected form­

ing word-groups and sentences.

A word-group is an intermediate link between a word and

a sentence. It is a grammatical unit formed by the combina­

tion of two or more notional words expressing one notion: the

latest news, the foreign policy of the British government.

A word-group, as well as a single word, can function as one

integral part of a sentence.

Northern Ireland is otherwise called Ulster.

A combination consisting of a structural word and a notion­

al word is called a phrase: in surprise — a prepositional phrase;

if necessary — a conjunctive phrase.

Most word-groups, as a rule, have one component which

can be regarded as the head-word.

According to the head-word, word-groups are classified as:

(1) noun word-groups, with a noun as the head-word: the Eng­

lish language, rules of grammar, an interesting book’, (2) adjec­

tive word-groups, with an adjective as the head-word: full

of interest, good at mathematics; (3) verb word-groups, with a

verb as the head-word: to write a letter, writing a letter; (4)

adverb word-groups, with an adverb as the head-word: very soon,

fairly well; (5) pronoun word-groups, with a pronoun as the head­

word: they both, some of you.

■ There are also word-groups without the head-word, in which

both components are equal: brother and sister, either you or me,

King Lear, Ann Brown, etc.

§ 7. When two words are connected syntactically, their

relation may be one either of coordination or subordination.

(1) Coordination means that both words are grammatically

equal: one does not depend on the other. Thus homogeneous parts

of the sentence are connected by coordination.

He rose up and went out. Mr Dick and I soon became the

best of friends.

z Coordination may be expressed by structural words (con­

nectors) and by word-order and intonation (asyndetic coordi­

nation).

Pete and John are good friends. Pete, John and'Dick are

good friends.

10

(2) Subordination means that the words are not equal gram­

matically: one word (adjunct) is subordinated to the other

(head-word).

Subordination may be in the form of agreement, government

and adjoinment.

Agreement is the repetition of the grammatical form of

the head-word in its adjunct-word:

this man — these men

All men are mortal.

Agreement is found: (1) between verb-predicate and subject;

(2) between attribute and head-word (demonstrative pronouns).

Government is the change of the grammatical form of a

word as a result of its association with another word.

I see him. He is John’s father. I am his brother.

Government is found: (1) between verb and object; (2) be­

tween head-noun and attributive adjunct (a noun in the pos­

sessive or possessive pronoun).

Owing to the fact that English nouns have no case inflex­

ions (except the possessive case), the English language employs

prepositions to indicate the relations of objects to the govern­

ing verbs. This is the so-called prepositional government.

I gave it to my friend (to him). I looked at my friend (at

him). I waited for my friend (for him). I rely on my friend

(on him). Tell me about your friend (about him).

Adjoinment is the adjoining position of two words joined

by the common grammatical function and meaning. It is the

most common way of connecting words in the English sentence.

Adjoinment is found: (1) between adverbs and verbs; (2)

between attributes and head-nouns; (3) between articles and

nouns.

A special kind of syntactical relation exists between subject

and predicate; this is the so-called predication. Being equal

in rank they are connected by agreement.

§,8. Linguists often use the terms “language” and “speech”.

What is the difference between these two terms?

*

• See: O. Jespersen. Essentials o/i English Grammar. Allen & Unwin LTD,

1969. Б. С. Хаимович, Б. И. Роговская. A Course In English Grammar.

M., «Высшая школа», 1967, p. 9—10.

Language is the system of paradigmatic relations, i. e. the

structure от various units and classes they form.

Speech is the system of syntagmatic relations, i. e. the com­

binations the same units form in the process of communication.

Language and speech are closely connected, for the life of

language consists in speech.

Sentences used in speech are not always such complete and

well-arranged as prescribed by the rigid rules of grammar.

Therefore the object in teaching living grammar is not only to

give rules but also to find out what is actually said and written

by the speakers of the language.

§ 9. Traditionally grammar is divided into morphology and

syntax.

Morphology includes the parts of speech and their grammat­

ical categories. Its object of study is the ways of changing gram­

matical forms of words.

Syntax includes the sentence and the parts of the sentence.

It studies sentence-building, i. e. ways of connecting words

and word-groups in sentences and, also, types of sentences.

Though morphology and syntax have their own objects of

study, they are closely connected. For the morphological charac­

teristics of a word are realized through its syntactical relations

with other words.

Each language has its own system of form-changing and

sentence-building. In dealing with the grammar of a particular

language it is therefore important to inquire into its peculiar­

ities.

As far as Modern English is concerned, it would be proper

to deviate from the traditional division of its grammar into

morphology and syntax.

As is known, most words in Modern English are very poor

morphologically. Therefore morphological characteristics can­

not be taken into account as the main point of classifying words

into parts of speech. Quite essential to this classification are

syntactical functions of words and types of word-groups they

form.

* For this reason, the present course of English is divided into

“Parts of Speech” and “Sentence-Structure” .*

• We fellow the division suggested by Л. С. Бархударов, Д. А. Штелннг

in the book Грамматика английского языка, Мм «Высшая школа»,

Part I

PARTS OF SPEECH

NOUNS

The noun is a part of speech denoting substances, i. e. things

(table, book), living beings (boy, dog), materials (air, gold) and

abstract notions (beauty, happiness, love, courage, struggle,

peace, progress).

The morphological characteristics of the noun are the follow­

ing:

(1) Countable nouns have the category of number expressing

singularity or plurality: a Student (singular) — students (plu­

ral).

(2) Nouns denoting living beings and some other nouns

have the category of case represented by two forms: the student —

the student's (book).

The main syntactical functions of the noun in the sentence

are those of the subject and the object.

The students passed their exams.

It may also be used as predicative, attribute and adverbial

modifier.

This is our teacher. He is the bods father. He is a teacher

of mathematics. I’ve been studying English for a year.

The noun is associated with the following structural words:

(1) articles: a book, the book; (2) prepositions: in the room, on

the table.

It may be modified by the following notional parts of

speech: (1) adjectives: a funny story, fine weather; (2) pronouns:

my brother, every student, this house; (3) numerals: five pages,

page five, the fifth floor; (4) verbals: the rising sun, the lost

letter, generations to come.

Besides, the noun may be modified by another noun: a

stone wall, a news report, birthday presents.

13

CLASSIFICATION OF NOUNS

Nouns can be classified in different ways.

I. All nouns fall under two groups: countables and uncountables.

Countable nouns denote things or individuals that can be

counted. These nouns have the grammatical category of number.

Uncountable nouns denote objects that cannot be counted.

The uncountable nouns are subdivided into the so-called singularia tantum and pluralia tantum.

II. According to their lexical meaning nouns fall under two

classes: common nouns and proper nouns.

Common nouns are names applied to any individual of a class

of persons or things, collections of similar individuals or things

regarded as a unit, materials or abstract notions. Common nouns

are subdivided into: (1) class nouns, (2) collective nouns, (3)

abstract nouns, (4) material nouns.

(1) Class nouns denote living beings or things belonging to

a class, such as a man, a dog, a book. They are countables.

(2) Collective nouns denote a number of persons or things

collected together to form a single unit. They are subdivided

into:

(a) Nouns that are used in both numbers: family, company,

crowd, nation, party, government, crew, team, committee, jury, etc.

When such a noun is used in the singular it may be followed

by the predicate verb either in the singular or in the plural. The

verb is singular if the collective noun is thought of as a single

unit. The verb is plural if the collective noun is thought of as

a collection of separate individuals.

The committee agrees to the proposal. The committee

are unable to agree.

(b) Nouns that are used only in the singular: linen, furni­

ture, machinery, money, youth,

(c) Nouns that are used^only in the plural: goods, belongings,

clothes, trousers.

(d) Nouns of multitude that are singular in form but plural

in meaning: people, police, cattle, poultry, such nouns are follow­

ed by plural verbs.

Note. The noun people is always plural In the meaning of «лю­

ди», but it has both numbers in the meaning of «народ».

(3) Material nouns denote materials: air, water, iron, *gold,

bread, milk, paper, cotton,.etc. They are uncountables.

14

(4) Abstract nouns denote notions: idea, science, informa­

tion, progress, unity; qualities: beauty, courage, humour, kind­

ness; states: life, death, happiness, peace, excitement, sleep; ac­

tions: work, struggle, conversation, reading, discussion; feelings

and emotions: love, hatred, pleasure, joy, sadness, anger, disap­

pointment. Most of them are uncountables.

Proper nouns are names given to individuals of a class to

distinguish them from other individuals of the same class.

Here belong: (1) personal names: John, Brown-, (2) geograph­

ical names: England, London, the Thames-, (3) the names of

the months and the days of the week; (4) the names of periodi­

cals, ships, hotels, clubs, etc.

NUMBER

Countables have two numbers — the singular and the plural.

In Modern English the singular form of the nouns is a stem

with a zero-inflexion.

The plural is formed by the inflexion -(e)s pronounced as

[zl, [si, [izl.

[zl dogs, days

[si hats, roofs

[iz] classes, roses, benches, bridges, dishes, garages

This is a productive way of forming the plural of nouns in

Modern English. However, certain nouns form the plural in

different ways, which cannot be regarded as productive. These

are survivals of earlier formations. Here belong the following:

(1) Vowel change in the root of a' word: man — men,

woman — women, foot — feet, tooth — teeth, goose — geese,

mouse — mice.

(2) Suffix -en: ox — oxen.

(3) Vowel change + suffix -ren: child — children, brother —

brethren (the latter is archaic and occurs only in high poetry and

religious prose).

(4) Consonant change + suffix -(e)s:

house — houses [s — ziz]

(

bath — baths

mouth — mouths

path — paths

calf — calves

half —halves

knife — knives

|

J [0—dz]

'

|

| [f—vz]

J

But:

truth - truths | (0_0 &]

youth — youths J

J

But:

hoof — hoofs, hooves) rf_fs vzi

scarf — scarfs, scarves/1

’ J

16

leaf —

life —

loaf —

shelf—

thief—

wife —

wolf —

leaves

lives

loaves

shelves

thieves

wives

wolves

Exceptions (no change

sounds):

[f — vz]

chief —

death —

month —

roof

—

in root

chiefs

deaths

months

roofs

(5) Homonymous forms for the singular and the plural:

deer — deer, sheep — sheep, swine — swine.

(6) Some words borrowed from Greek or Latin retain their

original plural forms.

Greek Loan-Words

Singular

basis ['beisis]

crisis ['kraisis]

analysis [a'naelasis]

thesis ['Gi: sis]

criterion [krai'tiarian]

phenomenon [fi'naminan]

„

Plural

bases ['beisi:z]

crises [Zkraisi:z]

analyses [a'naelaskz]

theses i'Gi:si:z)

criteria [krai'tiaria]

phenomena [fi'namina]

Latin Loan-Words

Plural

Singular

datum ['deitam]

data ['deita]

formula ['fa:mjula]

formulae ['fxmjuli:]

media ['mi:dja]

medium I'mkdjam]

memorandum [^ema'raendam]

memoranda [ymema'raenda]

series ['siari:z]

series Lsiari:z]

These forms tend to be used in the language of science. In

fiction and colloquial English the regular English plural form

in -(c)s is generally used.

Thus in some cases two plural forms co-exist: antennae,

antennas; formulae, formulas; memoranda, memorandums.

Uncountables are subdivided into two groups:

(1) Singularia tantum (nouns used only in the singular).

Here belong the following:

(a) Material nouns: air, water, wood, iron, etc.

, (b) Abstract nouns: love, courage, weather, information, etc.

(c) Some collective nouns: linen, furniture, machinery, etc.

(2) Pluralia tantum (nouns used only in the plural). Here

belong:

(a) Names of things consisting of two similar halves:

scales, scissors, spectacles, trousers, shorts.

(b) Some collective nouns: belongings, clothes, contents,

memories, savings, slums, stairs, outskirts.

(c) Some nouns formed from adjectives: goods, sweets, val­

uables.

(d) Some names of diseases: measles, mumps.

Note 1. In some nouns of this group the final *s loses the meaning

of the plural inflexion and the noun is treated as a singular. This Is the

case with the names of sciences and occupations ending in -ics: mathe­

matics, phonetics, physics, politics, tactics, which are generally considered

singular.

Phonetics is the science of spech sounds. But: Your phonetics are

very good, (not the science, but its practical application)

Here also belong such words as barracks, headquarters, works which

are used in the singular.

The headquarters consists of the.battalion commander and certain

members of his sta'ff.

Compare:

Politics is not in my line.— What are your politics?

Tactics Is the art of war. —Your tactics are wrong.

N о t e 2. The groups of singularia tantum and pluralia tantum do

not always coincide in the two languages under study.

(1) Such words as advice, information, knowledge, money, news *be

long to singularia tantum in English while in Russian they can be used

in both numbers (the words деньги being the exception).

No news Is good news. He knew nothing about money except how

to spend It.

(2) The words сани, часы and some others belong to pluralia tantum

in Russian but in English the words sledge and watch can be used in both

numbers: sledge — sledges, watch — watches.

Compound nouns form the plural in different ways.

(1) As a rule, a compound noun forms the plural by adding

-s to the noun-stem: mother-in-law — mothers-in-law, lookeron — lookers-on, passer-by —* passers-by.

(2) In some compounds the final element takes the plural

form: boy-friend — boy-friends, watch-maker — watch-makers.

(3) If there is no noun-stem in the compound, -s is added

to the last element: forget-me-not — forget-me-nots, merry-go-,

roundmerry-go-rounds.

17

(4) In case the second stem of a compound is the stem of a

noun with a non-productive form of the plural, the plural of

this compound is formed accordingly: house-wife — house­

wives, postman — postmen (both forms are pronounced in the

same way).

(5) Compounds having man- and woman- as the first stem

make an exception to the rule: their both stems have the plural

forms:

man-servant — men-servants,

woman-teacher — women-teachers.

CASE

Nouns denoting living beings and some others have the

category of case, represented by two cases: the common case

and the possessive case.

The common case has a zero-inflex ion.

The possessive case is the survival of the Old English geni­

tive case but its meaning and function is different in Modern

English. The possessive case is realized in the so-called possessive

construction (the possessive). The possessive is a combination

of two components tied up by the form-element (suffix) *s.

The first component can be represented by a noun or a noun wordgroup with the junction 's. The second component is a noun:

Mary's room, half a mile's distance.

The suffix ’s is pronounced in the same way as the inflex­

ion -(e)s of the plural.

If the first component is used in the plural -(e)s, we observe

the fusion of ’s-element with the plural suffix -(e)s (with a

simple apostrophe ’ in writing): students' books, a few hours'

sleep.

With other forms of the plural the suffix ’s is pronounced and

spelled as usual: men's clothes, children's games.

With proper names ending in [si or [z] the possessive element

is denoted by ’s in writing and is pronounced as [izl: Marx's

theory, Burns's poems, St. James's Park.

Compounds are treated as one word, with ’s after the second

stem: my mother-in-law's house.

When the first component is expressed by a group of

nouns connected by the conjunction and, the possessive suffix

’s is placed at the end of the noun word-group: John and Pe­

ter's room, but: John's and Peter's rooms.

The possessive construction is used in two cases:

(1) To express possession; in this case the first component

is normally represented by animate objects: Pete's book, Moth­

er's health, the woman's life.

W

The first component can also be expressed by such nouns as

the names of countries and towns or the words sun, moon, ship,

boat: Britain

*s

interests, the city's parks, the sun's fire, the ship's

course.

There is a tendency to use some other nouns denoting inani­

mate objects as the first component of the possessive.

*

Here

belong nouns denoting: (a) dwelling places and environment:

the apartment's five rooms, the garden's blossom, the sky's

blue, the river's bank; (b) certain social units and organizations:

the nation's future, the medical faculty's chair, the research group's

records; (c) social, political and economic phenomena: Big

Business' failures, the socialist economy's advance, the campaign's

success; (d) events in the field of art and sports: his book's suc­

cess, the play's style, the film's merits, the game's popularity,

hockey's fame; (e) vehicles and their details: the rocket's flight,

the liner's passengers, the sound of a car's brakes, the speedome­

ter's needle.

(2) To denote the qualitative characteristics of a thing;

in this case the function of the first component is like that of an

adjective: a children's room (детская комната), d Bachelor's

degree (степень бакалавра).

The possessive of this type is often used to express time and

space relations. The first component is represented by a noun or

a noun group expressing duration or distance: within a week's

time, after a moment's silence, in five minutes' walk, at a five

*

miles

distance.

Here also belong nouns denoting measures of weight and cost.

Macy’s sells a million dollars' worth of goods every day.

Its docks load and unload a few thousand tons' cargoes

every day.

In certain cases a noun in the possessive is not followed by

the second component — this is the so-called absolute posses­

sive.

The absolute possessive is

*used:

(1) When the second component is dropped to avoid unne­

cessary repetition.

“Whose umbrella is it?” “It’s Ann's." 1 parked my car

next to John's. We heard a howl, like a wolf's.

• See P. Christophersen, A. O. Sandved. An Advanced English Grammar.

Ldn., 1969.

19

(2) When this is introduced by the preposition of to denote

“one of many1’ (the so-called partitive possessive).

He is an old friend of my father's, (one of my father’s old

friends)

(3) In constructions with an of-phrase to express emotional

characteristics (such as disapproval, irony, neglect, etc.).

How do you like that silly joke of Jane's? That’s another

big idea of your uncle's.

When the word in the possessive denotes a shop, a plant, etc.

the ’s element loses the meaning of possession and is actually

used as a word-building suffix: at a chemist's (a hairdresser's,

etc.); a strike at Ford's; I’ve bought it at Macy's.

Proper nouns with the possessive element's are used to de­

note the place of residence: a dinner party at Brown's/the

Browns' .

GENDER?

The grammatical category of gender is not found in English

nouns.

In most cases the sex of animate objects is not indicated

grammatically. Most nouns have the same form for masculine

and feminine: parent, child, cousin, cook, singer, dancer, jour­

nalist, etc.

In some cases, however, such indications are expressed by

lexical means, i. e. by:

(1) the meaning of the word: man — woman, boy — girl,

lord — lady, bull — cow, cock — hen;

(2) the word-building suffix -ess: actor — actress, heir —

heiress, prince — princess, waiter — waitress, lion — lioness,

tiger — tigress;

(3) the first stem of a compound noun: boy-friend — girl­

friend, man-servant — woman-servant, he-wolf — she-wolf.

Sometimes inanimate objects are personified and are re-^

ferred to as belonging to the masculine or feminine gender.

Thus the sun is masculine, while (he moon is feminine. Also

feminine are such nouns as: earth, country, ship, boat, car, etc.

It is pleasant to watch the sun in his chariot of gold, and

the moon in her chariot of pearl. Ireland lost many of

her bravest men in the rebellions against England. The

ship struck an iceberg, which tore a huge hole In her bow.

20

ARTICLES

The article

*

is a structural word used as a determiner of

the noun. There are two articles in Modern English: the indef­

inite article a (an) and the def5nite article the.

Both articles have originated from pronouns.

The indefinite article has developed from the Old English

numeral an (one) which later acquired the meaning of an in­

definite pronoun (некий, какой-то, один). The original numeri­

cal meaning of the indefinite article is quite obvious in such

expressions as in a minute, at a time, twice a year, etc.

Owing to its origin from the numeral one the indefinite

article is not used before nouns in the plural. Its use is limited

to countable nouns in the singular.

The definite article has developed from the Old English

demonstrative pronoun that and in some cases it has preserved

this demonstrative meaning in Modern English: nothing

of the (that) kind, under the (those) circumstances.

These two articles are related to other determiners in the

following way: the = this, that, the same; a (an) = some,

any, such.

THE INDEFINITE AND THE DEFINITE

ARTICLES COMPARED

The indefinite article is used before a noun in the singular

to show that the object denoted by the noun is one of a class.

Therefore it may be qualified as a classifying article.

The indefinite article is generally used with countable nouns.

As a rule, it is not used with nouns of abstract or material

meaning.

The noun used with the indefinite article may have a nonrestrictive attribute. Such an attribute describes the person

or thing denoted by the noun by giving additional information

about it. This information only narrows the class to which the

object belongs.

* This book gives only a brief outline of the most essential points of

the topic. For details see: Л. С. Бархударов, Д. А. Штелинг. Грамма­

тика английского языка. М., «Высшая школа>, 1973, р. 47—48.

М. A. Ganshina, N. М. Vasilevskaya. English Grammar. М., Higher

School Publishing House, 1964, p. 46—78.

2b

She was wearing a necklace of red beads (one of such neck­

laces). A young girl of about sixteen wants to see you

(no more information is given to distinguish her from all

other girls). Father gave me a ten-dollar bill (but not a

pound). The President holds office during a term of four

years (but not for life).

The main cases of the use of the indefinite article are these:

(1) With a predicative noun, when the speaker refers the

object to a certain class.

My husband is a sailor.

(2) With nouns in other functions, when the speaker states

that the object denoted by the noun is one of a class (один,

какой-то, некий).

A lady is calling you up, Sir.

(3) When a noun serves as a typical example of a class:

what is said of one representative of a class can be applied to

any representative of the same class; here the article has the

meaning of “every”.

A policeman is always a policeman.

(4) When the indefinite article preserves its original numer­

ical meaning of “one”:

A week or two passed.

The definite article is used before a noun to show that the

object denoted by the noun is marked as a particular object,

distinct from all other objects of the class. That is why the def­

inite article is described as an individualizing article.

When the noun is used with the definite article the con­

text or the situation of speech shows that the mind of the speak­

er is concentrated on that particular object.

Ann is in the garden (= the garden of this house). He

sent for the doctor (= his own doctor). Please pass the

wine (=the wine on the table.). I’ll leave you a message

with the secretary (=the secretary of the office, or my

secretary).

The noun used with the definite article may have a restric­

tive attribute which shows that the meaning of the object is

restricted to such a degree that it can be easily distinguished

from all other objects of the same class.

2?

к

He saw a familiar face in the second row. Are you sure

the man you saw is the prisoner? I can tell you the very

moment I fell in love with her. She knew precisely the

right moment for doing the right thing. He was well-dres­

sed, the best-dressed man in the room.

Here are the three main cases of the use of the definite ar­

ticle:

(1) It may be used to identify a particular object denoted

by the noun. The object is made definite by the context (very

often, though not always, by being mentioned a second time)

or, rather, by the situation.

There is a tree in the garden. The tree is an oak. How

did you like the film? This is the house that Jack built.

In such cases the definite article retains its demonstrative

force, and is used in this meaning more often than the demon­

strative pronouns “this” or “that”.

Let me have the book. Дайте мне (эту) книгу.

(2) When the noun denotes a unique object (the earth, the

sun, the moon, the universe, the sky, the North Pole, etc.).

Kopernick proved that the Earth goes round the Sun. The

Universe is an awfully big place.

(3) When the noun is used in a generic sense, i. e. the object

is taken as the type embodying all the characteristic features

of the class and, for this reason, denoting the whole class.

The verb is a part of speech denoting an action. The tiger

is a big cat-like animal. The book deals with the novel

as a genre of epic literature.

Here also belong nouns in the singular and plural denoting

social groups and nations: the aristocracy, the bourgeoisie, the

proletariat, the workers, the working people, the Americans, etc.

Note that the nouns man and woman in a generic sense are used

without any article.

What an optimistic animal man is. Woman is not inferior of man.

“Why is woman weaker?” “Because man has done her so.” The

dog is man's best friend. There is no account for woman's logic.

THE ABSENCE OF THE ARTICLE

Sometimes no article is found before a countable noun.

Articles can be omitted for the sake of conciseness in head­

lines, telegrams, stage directions, etc. Here we speak of thestylis23

tic omission of articles, and, if inserted, they would not in­

volve a change of meaning.

Man Killed Saving Workmate. 10,000 In Anti-Nazi March.

Strike Over Government Wage Policy, (newspaper head­

lines) Mission accomplished according to plan. Arrived

here today. Letter following, (telegrams) Room crowded

with guests. Lady Windermere (sits on sofa): Puts book

back into desk, (stage directions)

In many cases, however, the absence of the definite or the

indefinite article has a meaning of its own, that of the so-cal­

led zero-form. Here the insertion of the definite or indefinite

article would bring about a change of meaning. Compare the

following sentences:

The book deals with problems of language.— English

is a Germanic language.— The language spoken in Hol­

land is called Dutch.

Thus the absence of the article may have generalizing force,

or in other words, the zero-form is a generalizing one. It shows

that the speaker does not have in view any individual object

(definite or indefinite) belonging to a class of similar objects,

but expresses a more abstract, a more general idea.

Therefore we find the zero-form with nouns used in the most

general sense, i. e., the names of materials (water, air, bread}

or the names of abstract notions (love, progress)

*

they are all

uncountable nouns.

SUMMING UP

When choosing an article one should remember the follow­

ing:

(1) The definite article has individualizing and generic mean­

ings, while the indefinite article has a classifying meaning.

She treated the teacher with the respect a teacher deserves.

The teacher may find it useful as a reference book.

(2) As said above, the indefinite article is not used with ab­

stract and material nouns taken in the most general sense.

Nor can it be used with countable nouns in the plural. In such

cases the zero-form of the article is to be used.

(3) Thus the definite article is opposed to the other two:

the Za И)

\zero

24'

That is the choice between a (an) and zero depends on the

class to which the noun belongs and its meaning in the context

(see Supplementary Notes).

(4) The definite article is also used to refer back to the object,

which has already been mentioned directly, or, at least, hinted

at. Compare the use of articles in the following sentences:

She murmured a name and the name was not Ralph. All

men and women are in a conspiracy to hide a secret, and the

secret that lies in the hearts of all men and women is that

they want to be loved.

(5) The definite and the indefinite articles can also be compar­

ed from a different angle.

While the definite article is used as a means of identifica­

tion, the indefinite article can serve as a means of indicating

the centre of the communication. It means that the noun deter­

mined by the indefinite article introduces the new object to

which the speaker’s attention is attracted at the given moment.

Compare:

The old man (we know what particular man is spoken about)

is crossing the road. — An old man (not a young one) is

crossing the road.

In the former example the mind of the speaker is concentrat­

ed on that old man: the speaker is watching him. In the latter

the speaker is watching the road and his mind registers a new

object on that road, i. e., an old man.

Also compare:

There stood a desk at the window. У окна стоял письмен­

ный стол.— The desk stood at the window. Письменный

стол стоял у окна.

SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES ON THE USE

OF ARTICLES

1. Articles with Material and Abstract Nouns

With nouns of material (water, air, bread, milk, sugar, tea,

iron, gold, cotton, etc), and abstract nouns (love, fear, truth,

time, science, grammar) taken in a general sense, no article is

used.

Time flies. Truth fears no lies. Blood is thicker than .wa­

ter.

29

Here also belong such uncountable nouns as work, weather,

advice, news, information, progress, permission, business, know­

ledge.

Work first, pleasure afterwards. No news is good news.

What delightful weather we are having. He will do well

in business.

The indefinite article may be used with material and ab­

stract nouns when the speaker wants to narrow the meaning of

the noun by denoting a sort of material or a certain amount of it.

Here is a wine you’ve never tasted, I’m sure. He was able

to mix a cocktail and tell a funny story. Seventy franks for

a beer?

When used with abstract nouns the indefinite article nar­

rows the meaning of something abstract in time or space or

gives it the meaning of something peculiar.

It was a wonderful time', the best time in my life. “Tess,”

he said in a preparatory tone after a silence.,. Soon he

saw a light in the distance.

Nouns of material and abstract nouns modified by the indef­

inite article are often used with a non-restrictive attribute. This

attribute narrows the meaning of the notion denoted by the

noun referring it to a certain class.

He is a national pride. There was an air of Importance

about him. I had seldom heard him speak withsuch an

intensity of feeling.

The definite article used with nouns of material and ab­

stract nouns expresses individualization.

She has never properly got over the feeling she used to

have. The wisdom of living is greater than the wisdom of

the book. She sighed for the air, the quiet and the liberty

of the country.

Compare the use of articles with abstract and material nouns

in the following sentences:

He died a soldier’s death in the cause of Democracy. We

must defend the democracy our forefathers have built in

this country. Oh, we are a democracy, all right. (= a

democratic country)

26

They emptied glass after glass of beer. The man said:

“Give me a beer too.” (one pint of beer) The beer they

were drinking tasted bitter.

2. Special Cases

(1) The nouns day, night, morning, evening when used without

an article express the general meaning of “light” or “darkness”.

Day was at hand. Outside it was night.

(2) The nouns breakfast, lunch, dinner, tea, supper, when

used without articles, have a more general meaning, that of

the time of meals or the process of eating.

I had breakfast earlier than usual. What shall we buy for

supper?

(3) No article is used with nouns in prepositional phrases in

the function of adverbial modifiers. Here belong prepositional

phrases with such nouns as school, college, hospital, court, church,

prison, town, market, bed, table; they are mostly used with the

prepositions at, in, into, to, from, after, etc. Nouns used in

these phrases denote activities or states connected with these

places, rather than places themselves.

They had been to school together. He is still in hospital.

What are you going to do after college? He was in prison,

wasn’t he? I would like to see him here as soon as he comes

in from court. I was told that the family were at table.

(4) When used with articles all these nouns retain their

full lexical meaning and are regarded as countables.

It was a warm summer night. The night being frosty, we

trembled from foot to head.

He settled back in his chair expecting a good dinner.

The dinner was very sound.

Hope is a good breakfast but a bad supper.

Maycomb was an old town. She said nothing all the way

to the town.

3. Articles with Proper Names

Proper nam.s are generally used without articles as the pro

*

per name in itself is to identify the person bearing that name.

So there is no need of using any additional means of identifica­

tion. The same is true of the nouns denoting members of a fam­

27

ily or relatives when these nouns are used as proper names:

Mother (Mummy), Father (Daddy), Aunt, Uncle, Nurse, Ba­

by, Child.

Here also belong the names of countries and towns, of months

and days of the week: England, London, January, Sunday.

No article is used with the following word-groups:

(1) A proper name with a preceding noun to denote the kind

of relationship: Sister Carrie, Uncle Tom.

(2) A proper name with a preceding noun to denote the

title, rank or scientific degree: King Lear, Lord Byron, Presi­

dent Roosevelt, Professor Smith, Doctor Alexander, Colonel Pic­

kering, also Mr Brown, Mrs Brown, Miss Brown.

(3) Proper names preceded by such adjectives as old, lit­

tle, young, poor, dear, etc.: Old Jolyon, Little Dorrit, Poor Tom.

(4) Geographical names with preceding adjectives: Northern

Ireland, Latin America, Ancient Rome.

The definite article may be used with proper names in the

following cases:

(1) To individualize a person so that the person in question

might not be cpnfused with someone else bearing the same name.

Michael, Mr Cassil is the Mr Cassil, the yery famous one

who writes the plays. (Here the individualizing force of

the first article is strengthened by the other two.)

(2) To denote a person, a country or a town in a certain

period of their existence.

*re

You

not the Andrew Manson I married. The England

of today is not what is used to be half a century ago.

(3) With the names of families in the plural: the Jacksons,

the Forsytes.

The Indefinite article may be used with proper names in

the following cases:

(1) To denote a person as belonging to the same family and

being its representative.

When a Forsyte was engaged, married or born, all the

Forsytes were present.

(2) To give the proper name the meaning of “some” or “cer­

tain ’ (какой-то, некий).

*

He was lodging by himself in the house of a certain Mrs

Jippings.

28

(3) To present the proper name as the embodiment of the

characteristic features of the type.

If you are a Napoleon, you will play the game of power.

Note. Traditionally, the definite article is used with such geo­

graphical names as these of:

(1) oceans, seas, lakes, rivers, channels, bays and gulfs: the Paci­

fic (ocean), the Mediterranean (sea), the Thames;

(2) archipelagoes: the West Indies, the Canaries;

(3) chains of mountains: the Alps, the Urals;

(4) deserts: the Sahara, the Gobi.

The definite article is used with geographical names expressed

by a word-group where the key element is represented by a common

noun such as sea, ocean, gulf, cape, etc.: the Black Sea, the Persian Gulf,

the Suez Canal, the Cape of Good Hope, the United Kingdom, the United

States, the Soviet Union (but: Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait, Cape Horn).

As an exception, the definite article is also used with the names of

some countries, territories, towns, streets, and squares: the Argentine,

the Congo, the Lebanon, the Netherlands, the Sudan, the Ukraine, the Ruhr,

the Caucasus, the Crimea, the Hague, the Strand, the Mall (but: Trafalgar

Square, Piccadilly Circus, Wall Street and so on).

Besides, the definite article is used with the names of:

(1) ships: the “Fearless", the “Potemkin";

(2) hotels: the “Astoria", the “Metropole";

(3) newspapers and magazines: “The Times", “The Guardian",

the “Life", the “Punch";

(4) organizations and parties: the United Nations Organization, the

Labour Party, the Royal Society;

(5) places modified by proper names: the Tate Gallery, the Lincoln

Centre, the Harvard Business School (but: Oxford University).

4. Articles with Noun Word-Groups

Here are a few more examples showing the use of articles

with nouns modified by different kinds of attributes. The choice

of an article is determined by the meaning of the attribute.

(1) Nouns modified by prepositive attributes

Restrictive

the very man —

the same story —

the only case —

Non-Restrictive

a certain man

a long story

a hard case

Note 1. The definite article is generally used with nouns modi­

fied by the superlative degree of adjectives to stress the unique character

of the thing or person; the indefinite article with nouns preceded by

most + ... has a non-restrlctive meaning emphasizing the intensity of the

quality expressed by the adjective (очень, чрезвычайно).

29

She was a most beautiful young girl; the most beautiful he had ever

seen

Note2. Ordinal numerals are usually associated with the def­

inite article as there may be only one thing (person) in a series denoted

by the numeral first or second, eto.

The indefinite article is used in word-groups with the words first,

second and third when it is not the question of tne order but that of enu­

merating or counting things (еще один, другой).

The first time we met was in April. Then came a second meeting

and a third one, and we met every other day.

(2) Nouns modified, by postpositive attributes

Non-Restrictive

Restrictive

the

the

the

the

the

(Which? Whose?)

message of the President

visit of the delegation

story of their love

majority of the voters

battle at Trafalgar

—

—

—

—

—

(What? What kind?)

a message of greeting

a visit of good will

a story of human interest

a majority of three votes

a battle of historic significance

Note 1. The definite article must be used with the nouns daugh­

ter, son, wiffi, husband. (The question to be asked is whose?).

N о t e 2. No article is used when a noun is followed by a cardinal

numeral (the stress being on the number): Part 1, page 15, number 3,

chapter 5, room 10, October 25; or: Cosmonaut No. 1, Lesson No. 2, etc.

X

5. Articles with Predicative and Appositive Nouns

(1) Predicative nouns

As is known, these are generally used with the indefinite

article. The definite article is used if the predicative noun is

modified by a restrictive attribute.

He is a famous explorer. He is the athlete who won the first

prize.

Note. If a predicative noun, denotes a unique post which can be

occupied by one person at a tinje, no article is used. (Such nouns are

usually used after the verbs be, appoint, elect.)

Mr R. K. Fern was President of Magnum Opus, Inc. He should be

elected Chairman. Who will be appointed Prime Ministerr

30

(2) Appositive nouns

The same rules arc applied to nouns in apposition.

The coach, a man of about fifty, watched them boxing.

This is Tommy, the boy who broke the window.

Note. If a noun in apposition stands for the name of a popular

person, the definite article is used.

Paul Robeson, the great singer and freedom fighter, will be seven­

ty-five tomorrow.

But if the person is not so popular, the indefinite article Is used.

The delegation was led by Miss Linda McDonald, a student from

Glasgow.

No article or, occasionally, the definite article is used when

the appositive noun denotes a unique post.

Mr Peterson, dean (the dean) of the college, is on holiday.

ADJECTIVES

The adjective is a part of speech denoting qualities of sub­

stances: size (big, small), colour (white, black), age (young,

old), material (wooden, iron), psychological state (angry, glad)

etc.

The main syntactical functions of the adjective are those

of an attribute and a predicative.

(This is) a difficult task.

The task is difficult.

1--------- 1

Adjectives in Modern English have no grammatical catego­

ries other than degrees of comparison. However, these are found

only within a group of adjectives which denote qualities vary­

ing in intensity.

Adjectives are closely associated with nouns (when used as

attributes) and linking verbs (when used as predicatives). They

are often modified by adverbs: very good, quite clear, still young,

rather late, too hard, etc.

Note 1. Adjectives with the prefix a-such as alive, asleep,

awake, etc. usually function as predicatives. When used .as attributes

theyfollow their head-nouns, thus preserving predicative character.

Is he awake or asleep? (predicative) He grew alarmed, awake

to the danger of his position, (attribute)

Note 2. The adjectives*111 ajid well are not used attrlbutlvely,

but only as predicatives.

31

My friend is ill again. I’m feeling very well.

Survivals of the old attributive use of ill arc found in some phraseological combinations: ill luck, ill news, ill wind, etc.

The adjective well is homonymous to the adverb well.

All is well that ends well.

CLASSIFICATION OF ADJECTIVES

According to their meaning and grammatical characteristics,

adjectives are divided into qualitative and relative.

Qualitative adjectives denote qualities of size, shape, col­

our, etc., which may vary in degree. Therefore qualitative

adjectives have degrees of comparison.

Qualitative adjectives have corresponding adverbs derived

by means of the suffix -ly (quick — quickly) or homonymous with

the adjective (fast — fast).

Relative adjectives denote qualities of a substance through

its relation to another substance, i. e. to material (wooden},

place (European), time (daily), etc. Their number is limited

in English.

Relative adjectives have no degrees of comparison..

DEGREES OF COMPARISON

There are three degrees of comparison:

(1) Positive: big, useful,

(2) Comparative: bigger, more useful,

(3) Superlative: (the) biggest, (the) most useful.

Adjectives in the superlative degree imply limitation and

therefore are preceded by the definite article.

There are the following ways of forming degrees of com­

parison:

(a) One-syllable adjectives form their comparative and super­

lative by adding -er and -est to the positive form (synthetical

way).

new — newer — newest

bright — brighter — brightest

(b) Adjectives of three or more syllables form their *

xompara

five and superlative by putting more and most before the posi­

tive (analytical way).

difficult — more difficult — most difficult

interesting — more interesting — most interesting

32

(c) Adjectives of two syllables follow one or other of the

above rules.

Those ending in -ful or -re usually take more and most.

careful — more careful — most careful

secure — more secure — most secure

Those ending in -er, -y, or -ly add- er, -est.

clever — cleverer — cleverest

pretty — prettier — prettiest

early — earlier — earliest

(d) Irregular degrees of comparison.

good — better — best

bad — worse — worst

little — less — least

(e) A few adjectives have two forms of comparison: the

second form has a special meaning and is actually a different

word.

far_ (further_ (furthest (of distance and time)

(farther

(farthest (of distance only)

_ (older

(oldest (of people and things)'

(elder (eldest (of people only)

Both further (furthest) and farther (farthest) are used with

the meaning of более (самый) отдаленный, but only further

may be used with the meaning of дальнейший, добавочный:

further information, further details, until further notice; elder

and eldest imply seniority rather than age. They are chiefly

used for comparison within a family: his eldest boy/girl/nephew,

my elder brother/sister; but elder cannot be placed before than>

so older must be used here: He is older than I.

Superlatives can be preceded by the and used as nouns.

Tom is the eldest. The eldest was only seven years old.

Comparatives can be used similarly.

His two sons look the same age. Which is the elder?

But this use of the comparative is considered rather literary.

In informal English a superlative might be used here instead.

Which is the eldest?

(f) In compound adjectives the first elerpent forms degrees

of comparison with -er, -est (if the two elements retain their

separate meaning).

2—501

33

well-known — better-known — best-known

good-looking — better-looking - bc< I-looking

But forms with more and most are more common,

old-fashioned — more old-fashionul — most old-fashioned

far-fetched — more far-fetched - most far-fetched

CONSTRUCTIONS WITH COMPARISONS

*

(a) Comparison of equals is expressed by as ... as — for

positive comparison and not as ... as or not so ... as — for nega­

tive comparison.

An apple is usually as big as an orange. A grape is not

so (as) big as an orange.

(b) Comparison of two unequal persons or things is expres­

sed by the comparative with than.

He is taller than his brother. A mountain is higher than

a hill. A stream is not wider than a river. This route is

two miles longer than that one.

But: This route is twice as long as that one. His 'salary

is several times as big as mine.

Twice (five times, etc.) as big (long, etc.) as ... is used to show

that one exceeds the other several times.

Note the use of pronouns and verbs after than and as:

(1) When than or as Is followed by a third person pronoun, we usu­

ally repeat the verb.

We are taller than they are. I am not as clever as he is.

(2) When than or as is followed by a first or second person pronoun,

it Is usually possible to omit the verb.

1 am not as young as you. He is better-educated than I.

(3) The pronoun, in formal English, remains in the nominative case

as it is still considered to be the subject of the verb, even though the

verb is not expressed.

(4) In Informal English, however, the pronoun is often put In the

objective case.

He is more persistent than me. They are wiser than us.

When the infinitive is used after than, the to of the infinitive can

be omitted.

It is sometimes quicker to walk than take a bus.

• For more details and examples see A. J. Thomson, A. V. Martinet.

A Practical English Grammar. Ldn., 1971, p. 13-45.

34

(c) Comparison of three or more persons or things is expres­

sed by the superlative with the ... of or the ... in (of place).

Tom is the cleverest boy in the class. She is the prettiest of

them all.

(d) Parallel increase is expressed by the + comparative ...

the + comparative.

The bigger the house is the more money it will cost. The

older he grew the wiser he became.

(e) Emphatic constructions.

Adjectives in the comparative and the superlative can be

made more emphatic by adding some adverbs (much, far, by

far, still, even) or adjectives (possible, imaginable). Comparatives

are preceded by much, far, still, even. Superlatives are followed

by possible or imaginable.

much larger, far more difficult

still larger, still more difficult

even larger, even more difficult

by far the largest, by far the most difficult

the largest thing possible, the most difficult task possible

It was the most difficult task imaginable. Surely, it is

by far the most likely explanation.

SUBSTANTIVIZED ADJECTIVES

I

The substantivization of adjectives is a kind of conversion.

Adjectives, when substantivized, lose all or part of the character­

istics of the adjectives and acquire all or part of the character­

istics of the noun. Thus in Modern English adjectives may be

either fully or partially substantivized.

Fully substantivized adjectives have acquired all the char­

acteristics of the noun: they have the plural and the possessive

and are associated with the definite and indefinite articles.

Here belong the following groups of words:

(1) Words denoting classes of persons, such as: a native,

a relative, a savage, a progressive, a conservative, a criminal,

a black, a white, etc.

(2) Words denoting nationalities: a Russian, an American,

a German, an Italian, a Greek, a Czech, etc.

N о t e that the nouns of this group ending in [z] or (si — Chinese,

Japanese, Swiss, Portuguese — nave homonymous forms lor the sin­

gular and plural: a Chinese — many Chinese.

2

35

(3) Words denoting periodicals: daily, weekly, monthly.

Partially substantivized adjectives take only the definite

article, but they do not have any other characteristics of the

noun. Here belong:

(1) Words denoting classes of persons who represent some

feature of human character, condition or state. These adjectives

are used in a generic sense: the good/bad, poor/rich, healthy/

sick, young/old, living/dead, wounded/injured (the poor = poor

people, the dead = dead people).

The poor are usually generous to each other. After the

battle they buried the dead.

These words are used as plural nouns and are followed by a

plural verb. If we wish to denote a single person we must add

a noun.

The old receive pensions. But: An old man usually

receives a pension.

Note that these adjectives refer to a group or class of persons con­

sidered in a generic sense. If we wish to refer to a particular group it is

necessary to add a noun.

The young are usually intolerant, (a general statement) But:

The young men are arguing, (particular young people)

(2) Words denoting nationalities ending in -sh, and -ch:

the English, the French, the Scotch, the Irish, the Welsh, the Dutch,

etc.

Note that a single representative of that nationality will be denot­

ed by.a compound noun: an Englishman, an Englishwoman.

(3) Words denoting abstract notions: the good, the beautiful,

the useful, the contrary, the impossible, the unknown, the opposite,

the inevitable. These words belong to singularia tantum.

I shall prove the contrary. The impossible had happened.

A number of such words are used in prepositional phrases:

In the negative, on the contrary, on the whole, for the better, in

the main, at large, in particular, in short, all of a sudden, etc.

(4) Words denoting things: goods, sweets, valuables,

They belong to pluralia tantum.

36

etc.

ADVERBS

The adverb is a part of speech specifying actions or qualities.

The function of the adverb in the sentence is that of an ad­

verbial modifier. Adverbs can modify verbs (ran quickly), ad­

jectives (very glad) and adverbs (fairly well).

Most adverbs do not change morphologically, but some ad­

verbs have degrees of comparison.

CLASSIFICATION OF ADVERBS

According to their meaning adverbs fall under several groups:

(1) adverbs of time: today, yesterday, tomorrow, now, soon,

after, before, yet, still, already;

(2) adverbs of place: here, there, anywhere, up, down, in,

out, upstairs, outside;

(3) adverbs of direction: forward, backward, away, north,

south, thence, whence;

(4) adverbs of manner: quickly, quietly, kindly, bravely,

strongly, fast, hard, well, together, thus;

(5) adverbs of frequency: once, twice, often, always, frequently, seldom, never, ever;

(6) adverbs of degree: very, fairly, rather, quite, too.

Adverbs of manner are usually formed by adding -ly to the

corresponding adjective: slow — slowly, bad — badly.

Some adverbs of degree are formed in the same way: extreme —

extremely, remarkable — remarkably.

Exceptions:

(a) Adjectives ending in -ly (friendly, lovely, lively, lonely,

likely) have no adverb form. We use a similar adverb or a

word-group instead.

likely (adj.) — probably (adv.)

friendly (adj.) — in a frieridly way (word-group)

(b) The following adverbs have the same form as their ad­

jectives: high, low, near, far, hard, fast, early, late, much, little.

a high mountain (adj.) — The bird flew high, (adv.)

a fast train (adj.) — She drives fast, (adv.)

Steel is hard, (adj.) — He works hard, (adv.)

(c) The adverbs in -ly formed from the same root have dif­

ferent meanings. Thus we find in English pairs of parallel ad­

verbs formed from the same root, one with the suffix -ly, the

37

other without it. As a rule, the derived form has a more abstract

meaning.

high высоко (в прямом смысле) — highly высоко (в

переносном смысле), благосклонно, похвально

deep глубоко (в прямом смысле) — deeply глубоко (в

переносном смысле), весьма, очень

near близко — nearly почти

close близко — closely тщательно, внимательно

late поздно, с опозданием — lately за последнее время,

недавно

t

Не praised her highly. I think highly of her. She is a

highly cultured person.

But: hard много, усердно — hardly едва

He works hard.— He can hardly say a word in English.

There are some adverbs formed from the roots of pronouns,

the so-called pronominal adverbs. They include adverbs of all

kinds and indicate time, place, manner, etc. in a relative way,

similar to that found in pronouns.

Adverbs of time: then, when, wherever;

— place: there, here, where, wherever, somewhere, any­

where, nowhere, everywhere;

— direction: thence, hence, whence, thither, hither,

whither; *

— manner: thus, so, how, why, therefore, wherefore;

— frequency: sometimes, always, ever, never;

— degree: so, somewhat.

Within this group of pronominal adverbs there is found a

group of conjunctive adverbs: when, whenever, how, why, where,

etc. These adverbs may be used as connectors introducing subor­

dinate clauses.

The pronominal adverbs, such as when, where, how, why may

also be used as interrogative adverbs introducing questions.

* These adverbs are archaic and occur only in poetry, high prose, scien­

tific writing (hence) and official documents.

38

DEGREES OF COMPARISON

Some adverbs of manner, degree and frequency have degrees of

comparison.

(a) In most cases they are formed by adding more and most.

quickly — more quickly — most quickly

cleverly — more cleverly — most cleverly

(b) One-syllable adverbs, however,,add -er, -est.

hard — harder — hardest

high — higher — highest

(c) The adverb early forms degrees of comparison in the

same way as one-syllable adjectives.

early — earlier — earliest

(d) Irregular forms:

well — better — best

badly— worse — worst

late — later — last

f _/ farther (farthest (of distance only)

lar

(further (furthest (used of distance, time, and

in an abstract sense)

CONSTRUCTIONS WITH COMPARISONS

Comparisons with adverbs are formed in the same way as

those with adjectives, i. e. we use: as ... as, not so... as, not

as ... as, several times as ... as and the comparative with than.

She dances better than I do (than me). I don’t drive as

(or so) fast as you (do). They arrived earlier than you.

Also: He ran fastest of all.

Most placed before an adverb can mean “very”.

He played most beautifully. She behaved most generously.

SUBSTANTIVIZED ADVERBS

Adverbs may be converted into nouns: these are adverbs of

time and place.

Their noun characteristics are quite obvious when they are

used in prepositional phrases.

I haven’t met her before today. There was no answer from

outside.

89

The substantivization of such adverbs as today, tomorrow,

yesterday, tonight is also obvious from the fact that they can

be used in the possessive and in the functions typical of nouns.

Have you read today's newspaper? Today is my birthday.

PRONOUNS

The pronoun is a part of speech including words with a very

general, or relative meaning. It is used as a substitute of a noun

or an adjective.

Pronouns indicate living beings, things and their qualities

without naming or describing them. It is always clear from the