Health Economics - 2015 - Guo - The Causal Effects of Home Care Use on Institutional Long‐Term Care Utilization and

advertisement

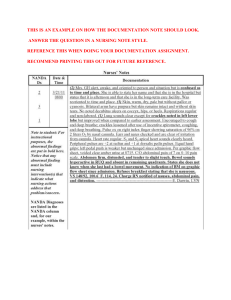

HEALTH ECONOMICS Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/hec.3155 THE CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE USE ON INSTITUTIONAL LONG-TERM CARE UTILIZATION AND EXPENDITURES JING GUOa,*, R. TAMARA KONETZKAb and WILLARD G. MANNINGc a b American Institutes for Research, Washington, DC, USA Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA c Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA ABSTRACT Limited evidence exists on whether expanding home care saves money overall or how much institutional long-term care can be reduced. This paper estimates the causal effect of Medicaid-financed home care services on the costs and utilization of institutional long-term care using Medicaid claims data. A unique instrumental variable was applied to address the potential bias caused by omitted variables or reverse effect of institutional care use. We find that the use of Medicaid-financed home care services significantly reduced but only partially offset utilization and Medicaid expenditures on nursing facility services. A $1000 increase in Medicaid home care expenditures avoided 2.75 days in nursing facilities and reduced annual Medicaid nursing facility costs by $351 among people over age 65 when selection bias is addressed. Failure to address selection biases would misestimate the substitution and offset effects. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Received 11 February 2014; Revised 23 August 2014; Accepted 22 December 2014 KEY WORDS: home care; institutional long-term care; instrumental variable 1. INTRODUCTION Developing and expanding home and community-based care (HCBS) alternatives to institutional long-term care (LTC) have been a priority for many state Medicaid programs in the USA and many OECD countries for at least the last two decades. This policy objective is a response to the fact that people generally prefer receiving LTC in their homes or communities rather than in nursing facilities or other institutional settings. This preference was written into law in the USA when the US Supreme Court, in what is known as the Olmstead decision, ruled that Medicaid must pay for HCBS for a Medicaid beneficiary so long as the cost of such care is not more than the cost of institutional care. However, adding to pressures to shift LTC services from institutional settings to HCBS is the fact that many nursing homes in Europe and the USA are aging. Renovating them to bring them up to building codes or replacing them will cost substantial amounts of money and as such often requires funds outside of budgets for operating expenses (Gerace, 2012). Many policy makers believe that providing home care can help control LTC costs by enabling people to live in less expensive settings than nursing homes. Most states in the USA have been shifting the delivery of Medicaidfunded LTC services from institutional care to community-based care in hopes of improving individuals’ satisfaction with care and controlling costs. Summary statistics illustrate this shift: In 2010, approximately 3.2 million people in the USA were receiving HCBS that were financed by Medicaid (Ng et al., 2014). As of fiscal year 2012, 34% of all Medicaid spending was for LTC services and half (49.5%) of that was for HCBS (Eiken et al., 2014). In 1998, LTC services accounted for 40% of all Medicaid spending and only 25% of that was for HCBS. Since then, HCBS as a share of Medicaid LTC spending has grown steadily because of annual increases in HCBS spending and declines in spending for institutional care (Eiken et al., 2014; Figure 1). *Correspondence to: Jing Guo, American Institutes for Research, Washington, DC, USA. E-mail: jguo@air.org Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE ON INSTITUTIONAL LTC 5 Source: KCMU and Urban Institute analysis of HCFA/CMS-64 data. “Growth in Medicaid Longterm Care Services Expenditures, FFY 1990-2009”, Kaiser Slides, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed July 2012, http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?ch=476. Reprinted by permission of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Figure 1. Growth in Medicaid long-term care service expenditures, federal fiscal year 1990–2009 However, policies promoting home care have been made on the basis of little rigorous evidence. There is a dearth of causal research about whether expanding home care saves money and provides cost-effective care at the individual level, especially for disabled adults and frail elderly individuals. Although many previous studies have been motivated by the question of whether home care can be a cost-effective substitute for institutional medical care, they offer limited evidence on the causal effect of home care use on the probability and costs of institutionalization. Existing studies suffer from many potential biases. A simple covariate adjustment model with endogenous predictors may result in biased inferences because of omitted variables, selection based on unobservables, measurement error, or reverse causality. An unbiased analysis of such an effect of publicly financed home care use on institutional care use that addresses selection bias in the choice to receive home care at individual level has not been achieved. Several key studies have explored the effects of Medicaid home care policy implementation on nursing home use at the state level (Muramatsu et al., 2007; Kaye et al., 2009). However, the analysis was either prone to omitted-variables bias from unobserved attributes correlated with state policy generosity or subject to ecological fallacies. In addition, given the lack of individual-level data, the connection between individual-level use of home care and individual-level institutional LTC use cannot be inferred. Although not directly relevant to public payers, a related body of work examines the causal linkage between unpaid informal care use and institutional LTC entry. Similar to the case of paid home care, potential selection and endogeneity problems complicate estimation of the true relationship between informal care and institutional care. Some studies that do not account for endogeneity find that the receipt of informal care complements or has no effect on institutional care (Newman et al., 1990; Jette et al., 1995; Spillman and Pezzin, 2000). Studies that find a substitution effect estimate institutional care cost savings too small to offset the costs associated with the noninstitutional health care (Kemper et al., 1986; Kemper, 1988). However, a number of studies have attempted to address the key endogeneity issues to assess the true causal effect of informal care use on the risk of using institutional care. Bivariate probit methods (Lo Sasso and Johnson, 2002), availability of children (Van Houtven and Norton, 2004, 2008), and family structure characteristics (Charles and Sevak, 2005) have been utilized to partially address endogeneity in the choice of receiving informal care, and these studies found some substitution between informal home care and institutional care use. It is not clear whether these findings apply to the effect of paid home care, a service with a more direct and tighter connection to current public policy, and they are not relevant to the direct cost implications of substitution among types of publicly financed LTC. In addition, unbiased estimates of the size of the effects of Medicaid-financed home care on institutional LTC and costs are needed. Following the vast majority of previous studies (Jette et al., 1995; Lo Sasso Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 6 J. GUO ET AL. and Johnson, 2002; Van Houtven and Norton, 2004, 2008; Charles and Sevak, 2005; Muramatsu et al., 2007), we also separate the elderly from the nonelderly disabled recipients in this paper. To our knowledge, this is the first study to address selection and endogeneity issues in estimating the causal effects of individual-level Medicaid expenditures for home care on institutional LTC utilization and costs. We use a unique longitudinal data set and a randomized assignment that encouraged receipt of Medicaid-financed home care but is not related to institutional care entry per se. This permits the use of an instrumental variable (IV) to eliminate potential endogeneity bias. A set of baseline disease history and health status attributes was included to further reduce omitted-variables bias and to enhance the overall precision of the results. We find that increased Medicaid home care expenditures significantly reduce use and costs of nursing facility services, but such offsets are not complete. These findings are robust to a number of checks. Not addressing endogeneity issues would misestimate the substitution and offset effects. The remainder of this paper starts with our empirical approach in Section 2 that characterizes methodological solutions relevant to examining the causal effect of receiving home care on institutional care use. Section 3 presents the empirical results with a series of sensitivity analyses and robustness checks. Section 4 discusses the policy implications of our findings. 2. METHODS 2.1. Goals of the empirical analysis We might expect home care to serve as a substitute for nursing home care primarily because, when LTC services are needed, help with functional and cognitive impairment in the home may delay or eliminate the need for the same type of care in a nursing home. On the other hand, while perhaps less likely, nursing home care might serve as a complement to home care if the increased attention through home care leads to recognition of substantial unmet needs that may require the higher level of care available in a nursing home. In addition, the quality of home care versus institutional care may affect the nature of the relationships. The goal of this study is to estimate the extent to which the substitution effect expected by policy makers emerges empirically as a causal effect. 2.2. Empirical strategy 2.2.1. Endogeneity and instrumental variable approach. Because expenditures for home care and the use of institutional care may be endogenous, there are at least two sources of bias that need to be considered when estimating the causal effect of Medicaid home care expenditure on institutional care use and costs. First, use of home care and use of institutional care are each likely to be correlated with unobserved factors, such as the availability and quality of informal care, home environment, and negative health characteristics. As a result, the potential for omitted-variable bias exists and needs to be addressed. Second, because the risk of needing institutional LTC may influence a person’s decision to obtain HCBS (reverse causality) and use of home care may lead to use of institutional LTC, simultaneity bias is another possibility that needs to be addressed. Failure to address these sources of bias could lead to inconsistent estimates. Depending on the nature of the omitted variables, the inconsistency from simple covariate adjustment could go in either direction. To obtain consistent estimates, we take advantage of an existing randomized assignment that encouraged receipt of Medicaid-financed home care but is not related to institutional care entry per se. We use this assignment mechanism to instrument for the endogenous Medicaid home care expenditures, with other covariates controlled for. This randomized assignment status is drawn from Medicaid claims data for adult enrollees of the Cash and Counseling Demonstration and Evaluation (CCDE) program.1 We are not evaluating that same experiment but rather using the randomization in that experiment as an IV for our own research question. However, we provide some details about the original Cash and Counseling experiment so that readers may assess the validity of the instrument. 1 The CCDE Medicaid claims data are publicly available on the Web at http://198.87.1.39/ccda/. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE ON INSTITUTIONAL LTC 7 Table I. Key features of CCDE intervention Control (agency-based Medicaid) Home care provider Counseling service Medicaid-certified agency N.A. N.A. Treatment (consumer directed) Medicaid-certified agency Family, friends, or trusted persons (allowance) Help patients manage home care and supervise allowance CCDE was designed to assess whether a more flexible consumer-directed manner of receiving Medicaid home care services could improve the outcomes of beneficiaries and their caregivers without increasing Medicaid costs per recipient for such services (Dale and Brown, 2007a). Rather than randomizing all Medicaid recipients, the demonstration enrolled those eligible Medicaid beneficiaries with previous home care use who volunteered for the Cash and Counseling program and consented to randomization (Doty et al., 2007). Arkansas, New Jersey, and Florida participated in a three-state demonstration. Enrollment occurred from December 1998 to July 2002 with up to 24 months of follow-up. After completing a baseline interview, half of the demonstration enrollees were randomly assigned to the treatment group, whose members were eligible to receive counseling services that help them manage their home care needs and a monthly allowance, which they could use to hire workers and to purchase care-related goods and services under supervision. The other half of the enrollees were assigned to the control group, whose members had to obtain their Medicaid home care services through the traditional agency-based model. The key components of the CCDE intervention are listed in Table I. Although expanding the amount of home care services used by the treatment group was not a primary goal of the intervention, this is what happened. Cash and Counseling expanded the supply of home care workers because treatment group participants were allowed to hire family and friends. This, combined with participantdirected care, led to greater satisfaction with home care and thus greater use than that observed in the control group. Brown et al. (2007) reported that, on average, the treatment group received more paid care than the control group, and Medicaid home care costs were significantly higher for the treatment group than for the control group, both overall and among recipients. The main analysis of this study limits the sample to adults who were age 65 or older and enrolled in Medicaid full time during the first year postrandomization of the CCDE study period.2 2.2.2. Measurement. The dependent variables of interest over the first year of the CCDE study period are an individual’s utilization of and Medicaid expenditures for institutional LTC, specifically nursing facility services provided by Medicaid-certified nursing homes. For each person in the data set, the number of days per year in nursing facilities is captured from Medicaid claims data. To calculate Medicaid expenditures for institutional care for anyone with days of institutional care, we use annual Medicaid expenditures on nursing facilities directly drawn from the Medicaid claims data.3 Because of the considerable percentage (91%) of dual eligible consumers in this sample and the different coverage between Medicaid and Medicare (Dale and Brown, 2007b), the Medicaid cost measurement does not reflect the total cost of institutional care but rather provides evidence on cost from a state Medicaid perspective. The distributions of the dependent variables are presented in Table II. The key explanatory variable is the total cost for Medicaid home care services in the first year of the CCDE study period. Medicaid home care services include non-medical services provided to assist with activities of daily living (such as bathing, dressing, light housework, medication management, meal preparation, and transportation). Medicaid also pays for case management, caregiver respite, and devices and appliances that 2 Tests on baseline variables comparing the treatment arms suggest that this sample exclusion does not appear to introduce statistically significant selection bias to the randomized study at a 10% significant level based on observed variables. Pre-randomization attributes (94%) were not significantly different across the two groups at a 5% significant level (Table III). 3 As discussed in the limitations in Section 3.3.3, there are caveats associated with this measure of nursing home expenditures. However, because costs come directly from the Medicaid claims data and constitute an important outcome in this context, we present our research design and results on Medicaid expenditures followed by a discussion of the caveats. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 8 J. GUO ET AL. Table II. Descriptive statistics (mean and SD) of dependent variables (N = 2810) Dependent variables Any nursing facility days Nursing facility days Nursing facility days if >0 Any Medicaid nursing facility costs Medicaid nursing facility costs Medicaid nursing facility costs if >0 Mean SD 14.02% 12.39 88.37 8.43% $962.95 $11,417.22 0.35 47.61 97.33 0.28 4522.78 11117.95 help an individual live at home—but we are not including expenditures for these services in our estimate of Medicaid home care costs. ‘Costs’ and ‘expenditures’ in this context are just the total payments made by the Medicaid program to reimburse medical providers for treating the beneficiary during the first year of the CCDE study period. These total payments best approximate the cost to the state’s budget, and costs are the best way to proxy for the intensity of Medicaid-financed home care treatment. We include covariates for the participant’s demographic and socioeconomic status, including gender, race, ethnicity, baseline age, a fixed effect for state of residence, potential informal care resources at baseline, and a set of health status and health spending measures.4 Contemporaneous Medicaid costs for counseling and hospice were also included in the regressions. Descriptive statistics of the independent variables are listed in Table III. 2.2.3. Modeling health expenditure and utilization. Because relatively few people among the sample participants did use institutional care, the distributions of the outcome variables have a large mass at zero5 (Table II). Thus, we use a two-part model (2PM) to estimate the impact of using home care on institutional LTC use and spending. The first part of the 2PM estimates the risk of any institutional care use or the probability of positive Medicaid institutional LTC expenditures using a logit model, while the second part estimates the institutional care days or the amount of such Medicaid costs conditional on having any use. In the second part, expenditures and utilization among those with any institutional care were extremely right skewed. To take this issue into account in the second part and avoid the potential bias problems in retransformation, generalized linear models (McCullagh and Nelder, 1989) are used and specified with log link and the gamma family of distributions based on a series of model specification tests. When conducting IV analysis, we used a two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) technique, the preferred approach when using nonlinear models (Terza et al., 2008). The first-stage 2SRI residual is based on all analysis observations and is included in both parts of the model. The 95% confidence intervals of the marginal effects from recombined models are obtained via 1000 nonparametric bootstrap replicates on the whole analysis sample using the percentile method (Efron, 1987). 2.2.4. Validity of the instrumental variable. There are three requirements for a valid instrument (Bound et al., 1995; Staiger and Stock, 1997). First, the instrument, the CCDE random assignment status, must affect the endogenous independent variable, Medicaid home care expenditures. Our instrument should satisfy this condition because CCDE increased home care use among people in the treatment group relative to those in the control group (although being assigned to the treatment group was by design not intended to affect the amount spent on home care, it did because some people in the control group could not find a care provider or did not want a provider from an agency). Thus, the CCDE random assignment process appears to affect the independent variable. Second, the instrument should be a strong predictor of the endogenous independent variable after controlling for all other exogenous variables. The first-stage IV power tests presented in Table IV6 suggest that the instrument is still highly predictive of endogenous Medicaid home care expenditures after controlling for all other exogenous covariates. 4 Because all the individuals in this sample were eligible for Medicaid, which is a health care program for disabled people and families with low incomes and resources, all participants were of low income, and the limitation of missing income is minimal, given the randomized design. Skewness >1.25, kurtosis >3.37. 6 Although some of the endogeneity tests are not statistically significant, this is likely because of lack of power, and the sizable differences in the magnitudes of the coefficients are practically meaningful. 5 Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 9 CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE ON INSTITUTIONAL LTC Table III. Descriptive statistics of independent variables (analysis sample, N = 2810) Independent variable First year Medicaid home care costs Control variable set 1: other health care costs First year counseling costs First year hospice costs Control variable set 2: baseline status (%) Gender Female Age Age 80+ State Arkansas Florida New Jersey Race and ethnicity White Black Other races Hispanic Potential informal care resources Married Live alone Unpaid help: personal care Unpaid help: transport Unpaid help: routine healthcare Unpaid help: house/community Health status and disease history Poor health (self-report) Skeletal Skin high cost Renal related_medium Renal related_high Cancer Cardiovascular Central nervous system Diabetes type 1 Diabetes type 2 Gastrointestinal Hematological Infectious Metabolic Psychiatric Pulmonary Control (N = 1402) Treatment (N = 1408) p-value 7432.38 (7527.99) 9089.54 (7192.86) Wald test 0.00*** 0.12 (4.61) 38.30 (933.85) 2536.61 (4701.80) 72.70 (1454.76) 0.00*** 0.46 Pearson test 79.53 81.61 0.15 46.65 43.82 0.27 43.51 26.68 29.81 42.54 27.70 29.76 0.83 59.34 29.32 6.28 22.68 62.36 31.32 6.32 22.02 0.61 17.86 66.46 68.41 54.69 64.00 82.44 17.84 68.54 66.41 53.95 63.30 80.68 0.37 0.54 0.26 0.69 0.70 0.23 40.14 20.14 8.42 28.67 4.63 13.60 37.38 5.42 18.26 20.47 6.13 7.56 7.63 8.77 2.07 10.13 42.70 18.04 9.16 27.20 4.62 13.64 38.85 3.98 19.39 20.31 7.81 7.88 7.67 7.39 1.78 11.79 0.38 0.16 0.49 0.38 0.98 0.99 0.42 0.07* 0.44 0.92 0.08* 0.75 0.97 0.18 0.57 0.16 0.45 The comparisons between the two treatment arms are calculated based on simple two-sample t-tests without corrections for multiple comparisons. In the control group, only one person had used counseling services with related cost of $172.5 during the first year of randomization. ***Significance levels of 1%, **5%, and *10%, respectively. Finally, a valid instrument also must satisfy the exclusion restriction. In our case, this means that the instrument of randomly assigned CCDE intervention must be uncorrelated with institutional care use and costs other than through Medicaid home care costs, conditional on other observed or omitted characteristics. Although the exclusion restriction cannot technically be tested with a single instrument, the use of a successful randomization greatly reduces the likelihood of correlation between the instrument and the error term in this model. Thus, the use of the CCDE as an instrument for home care use plausibly minimizes the risk of unmeasured selection into treatment based on health status or social support. Although the CCDE intervention of the treatment group only provided services to promote home care use and did not address institutional care services, several potential pathways to the outcome other than home care use Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 10 J. GUO ET AL. Table IV. Specification tests for the instrumental variable (N = 2810) Strength of the instruments Dependent variable Main model Nursing facility days Medicaid nursing facility $ Sensitivity analysis—heterogeneity treatment Nursing facility days Medicaid nursing facility $ Hausman exogeneity test—regression form Statistics (χ 21 ) p-value Statistics (χ 22 ) p-value 97.25*** 97.25*** 0.00 0.00 1.2 1.17 0.19 0.36 86.74*** 86.74*** 0.00 0.00 7.41 2.77 0.04 0.11 ***Significance level of 1%. Table V. Simple two-sample t-tests for Medicaid-type services on analysis sample (N = 2810) Medicaid-type service Home care Nursing facility services Inpatient Transportation Home health services Prescription drugs Durable medical equipment Treatment group Control group t-test $9090 $760 $741 $221 $236 $2777 $191 $7432 $1167 $837 $247 $226 $2870 $210 *** *** ***Significance level of 1%. need to be discussed in order to evaluate the exclusion restriction further. First, the exclusion restriction would be violated if the counseling services received by treatment group participants directly affected the receipt of institutional care other than through the home care effect. However, the dollar amount of used counseling services is controlled in every model and is found to have no statistically significant effect7 on institutional LTC use and costs, indicating that using counseling services is unlikely to be driving the findings in this paper. It is also possible that other types of health care utilization may have increased for the treatment group and affected institutional care use simultaneously. However, the data in Table V do not suggest that enrolling in the treatment group is significantly associated with use of hospice, prescription drugs, home health services, or purchase of durable medical equipment. Thus, the instrument appears to be robust to major potential threats to the exclusion restriction and to satisfy the standard strength and validity requirements. Although as with all IV analyses, we cannot definitively rule out all other pathways that might threaten the validity of the instrument,8 we believe that any remaining bias is likely to be minor. 3. RESULTS The main analyses are conducted under the assumption that the causal effects of paid home care on the utilization and Medicaid costs of nursing facility services are contemporaneous, that is, occurring within the same year without regard to timing. Home care may precede and eliminate the need for institutionalization, or the availability of home care may shorten an institutional stay that precedes the home care.9 Thus, we draw on both p-values >0.33. Another possibility is that enrolling in the treatment group affects institutional care use through a potential household income effect because only treatment group participants could hire family members as home care workers, which might lead to a higher household income level. However, the risk of violating the exclusion restriction through this potential household income effect should be minimal for this population because they were all on Medicaid and were not paying for nursing home services during the study period. We further test for this possibility by taking advantage of a variable indicating whether family members were hired and find that hiring relatives is not significantly associated with institutional care use. 9 During the baseline year of CCDE (12 months after enrollment but before randomization/treatment), 284 out of 2810 elders in the analysis sample used nursing home services. On average, the users (N = 284) stayed in a nursing home for 39.63 days with SD of 48.19 before randomization. 7 8 Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 11 CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE ON INSTITUTIONAL LTC Table VI. First-part logit model marginal effects of $1000 Medicaid home care increase per year (N = 2810) Non-IV model P-hat Nursing facility days Medicaid nursing facility costs 13.5% 8.1% Coefficient IV model ME 0.088 (0.014)*** 0.127 (0.019)*** 1.0%*** 0.9%*** Coefficient ME 0.137 (0.046)** 0.167 (0.058)*** 1.5%** 1.2%*** % of sample mean 11.1% 14.8% ***Significance levels of 1% and **5%. Table VII. Combined two-part model marginal effects of $1000 Medicaid home care increase per year (N = 2810) Non-IV model ME Nursing facility days Medicaid nursing facility costs 2.33*** $269.63** IV model 95% CI [ 3.79, [ $637.01, 0.85] $27.32] ME 2.75*** $351.31** 95% CI [ 4.10, [ $782.43, 0.71] $63.10] % of sample mean 22.2% 36.5% ***Significance levels of 1% and **5%. scenarios to assess whether in total the receipt of home care affects the utilization and costs of institutional LTC. The results are presented in Tables VI and VII. 3.1. Nursing facility days Results from the first-part model indicate that Medicaid home care expenditures had a strong negative effect on the likelihood of using nursing facility services. The coefficient within the IV model was markedly larger than the one obtained from a non-IV multivariate model that did not explicitly address endogeneity. An 8.9% average chance of using nursing facility services is predicted by this logit model. According to the IV estimation, a $1000 increase in Medicaid home care expenditures for the average individual in our sample significantly reduces the probability of nursing home use by 1.5 percentage points, which is 11% of the sample mean. The combined two-part IV model suggests that Medicaid spending on home care was associated with a significant reduction in annual days living in nursing facilities. A $1000 increase in Medicaid home care expenditures per year lowers nursing facility stays by 2.75 days across the full sample when endogeneity is addressed, which is 22% of the sample mean and statistically significant. 3.2. Medicaid nursing facility costs Similarly, increased Medicaid-funded home care significantly reduced the likelihood of generating any Medicaid nursing facility costs. The coefficient from the IV model is almost twice the non-IV model result, indicating that the IV correction was meaningful. According to the IV logit model, a $1000 increase of Medicaid home care expenditures reduces this probability by 1.2%, which is 15% relative to the sample mean. The combined 2PM suggests that a $1000 increase per year in Medicaid home care expenditures per beneficiary significantly lowers annual Medicaid nursing facility expenditures by $351.31 across the full sample when endogeneity is addressed, which is 36.5% relative to the sample mean. 3.3. Sensitivity analyses We conduct a series of robustness checks. These include the estimate of the home care effect on long stays (>60 days) for nursing facility services to eliminate potential rehabilitative care under Medicare, a model on the participants who showed nursing facility use but did not generate Medicaid costs associated with their Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 12 J. GUO ET AL. institutional care10 to check whether the studied effect is different for this population compared with the whole sample, a subsample analysis on the treatment group enrollees who did not use counseling services, in order to check whether the previous findings might be driven by counseling services11, and analyses to test the robustness of 2SRI results using control function approaches12 (Heckman and Robb, 1985; Newey et al., 1999; Garrido et al., 2012). These sensitivity analyses provide qualitatively similar answers but occasionally significant differences. We focus on two of these robustness checks in detail in the succeeding texts. 3.3.1. Heterogeneity in treatment. Because enrollees in the treatment group of the CCDE were allowed to hire their family members or friends to provide home care services, the home care costs in the Medicaid claims data were generated by two types of home care: traditional agency-based home care and non-agency-based care provided by family or friends. In contrast, by policy and study design, participants in the control group were limited to agency-based services. Thus, expenditures on home care in the data may incorporate some heterogeneity in the actual care provided to people in the treatment group. That is, the home care use might come from two different types of services. Although this ‘heterogeneous treatment’ issue arises in almost all randomized social experiments and does not affect the validity of the instrument, it could affect policy implications about what types of home care should be encouraged to reduce institutional care use. In order to assess sensitivity of the results to heterogeneous types of paid home care, we repeated the analysis controlling for a home care type variable drawn from the program’s 9-month survey data13 asking whether enrollees had only unrelated paid caregivers. The results presented in Table VIII strongly supported the findings in the main analysis, even when accounting for heterogeneous treatment. Thus, heterogeneity of the treatment does not appear to be a significant problem in interpreting the results. 3.3.2. Effect of home care on subsequent institutional care admissions. The results presented previously assume that the effect of home care on institutional care use and costs was contemporaneous; that is, receipt of more hours of home care or more hours of intensive care during the year results in lower use of institutional care that year. Because home care use might delay institutional care entry, we test the robustness of our analysis under an alternative assumption that the risk of nursing facility entry was affected by past paid home care. The explanatory variable in this model is the monthly average Medicaid home care cost before the first nursing facility entry. Cox proportional hazard modeling with IV was conducted to estimate the causal effect. This approach allows the use of the original CCDE 2-year sample (N = 3184). This survival analysis treats death,14 Medicaid disenrollment, and end of CCDE program as random right-censoring events. The first stage is estimated on log-transformed monthly Medicaid home care expenditures before the first nursing facility use based on a martingale residual test (Fleming and Harrington, 1991). Table IX shows the estimates of the main model and the estimates on nursing facility entry during the first year for the 12-month Medicaid enrollment sample. Then, the survival analysis is extended to 1 and 2 years. With the IV model, a 100% increase in previous monthly Medicaid home care expenditures significantly reduced the risk of future nursing home entry by 14.4% during the first year among the full-time Medicaid enrollment population, which could be estimated as 1.78-day delay in this sample. Without controlling for potential endogeneity bias in the non-IV model, this substitution effect is much smaller and not statistically significant. Thus, the survival model suggests that under the alternative assumption about the timing of the home 10 Because of potential coverage by other payers such as Medicare or potential data errors The particular counseling services mentioned in this paper were designed for CCDE and offered to the treatment group (Doty et al., 2007; Table III), although Medicaid programs in different states might have other forms of fiscal/counseling services that could be received by both control and treatment groups. 12 One of the control function approaches significantly rejected 2SRI, although the directions of the estimated marginal effects are still the same and the magnitudes have not been largely changed. Further studies on proper measurement of residuals or deviances are needed. 13 Because this question was only asked in the 9-month survey, all the costs and utilization variables in this sensitivity analysis were accumulated to the first 9 months after Cash and Counseling experiment randomization. 14 The death rate of this sample is 12.8% during the 24-month study period and 6.8% during the first year after CCDE randomization. 11 Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 13 CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE ON INSTITUTIONAL LTC Table VIII. Sensitivity analysis for heterogeneity treatment (N = 2810) Non-IV model IV model ME First-part logit model Nursing facility days Medicaid nursing facility costs Combined two-part model Nursing facility days Medicaid nursing facility costs ME 1.00%*** 1.00%*** % of sample mean 1.10%** 1.10%*** 2.71*** 273.71** 2.83*** 329.07** 18.10 18.50 26.40 35.80 ***Significance levels of 1% and **5%. Table IX. Effect of home care on subsequent institutional long-term care admissions Non-IV model IV model Nursing facility use Hazard ratio Hazard ratio First year full-time Medicaid (N = 2810) No. of nursing facility entry = 394 First year full sample (N = 3184) No. of nursing facility entry = 515 2-year full sample (N = 3184) No. of nursing facility entry = 830 101.80% 85.60% 102.50% 96.00% 93.70%*** 91.90% ***Significance level of 1%. care causal effect, increased Medicaid home care expenditures still significantly reduce subsequent use of nursing facility services, but these offsets are limited as well. 3.3.3. Limitations. One standard issue in interpreting the IV estimates is that not every observation’s behavior is affected by the instrument. In this study, not every treatment group participant used more Medicaid-financed home care services, even if they were allowed and encouraged to do so by the CCDE intervention discussed previously. Therefore, the IV approach in this paper only provides an estimate for a specific group of people whose behavior can be changed by the instrument—the CCDE intervention. The fact that the IV estimate is a local average treatment effect sometimes may limit generalizability (Imbens and Angrist, 1994). However, in this case, it seems reasonable to think that the group that the estimate is based on is one appropriate group for policy. In addition, although the study sample is a group of Medicaid enrollees with home care needs, the needs are largely because of mild to moderate physically impairment, and only 3% of the participants had psychiatric disorders (Table III). So, the results may not apply to people with severe cognitive impairment or people who need a high level of skilled care available in a nursing home. Finally, although we did not have the power to estimate state-specific effects, the treatment effect that we estimate may vary from state to state because of variation in existing state coverage of HCBS, Medicaid rates, and regulatory constraints on supply. To support decision making by policy makers through evidence-based research, the generalization of efficacy studies from a controlled experiment to more real-world conditions is essential yet challenging. The study sample of this research is drawn from a randomized experiment with voluntary participation in three states under Medicaid coverage over a limited time period. The findings should be reasonably generalizable to the extent that the participants are representative of Medicaid adult beneficiaries who would enroll in an ongoing program and have home care needs.15 However, the size of the substitution effect might be different 15 In order to identify to what extent the external validity is threatened in this study, we compare this analysis sample with the national population of users of HCBS in 2005 on several selected characteristics reported by Konetzka et al. (2012) in Table X. In general, the observed distributions are very similar between the two samples, and the generalizability concerns based on socioeconomic status should not be severe. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 14 J. GUO ET AL. Table X. Selected characteristics of Cash and Counseling Demonstration enrollees Selected characteristics Demographics Age (mean years) Female (%) Race or ethnicity White Black or Hispanic Other race Race unknown 2005 HCBS population CCDE population 78.52 74.41% 78.13 80.53% 54.58% 27.96% 9.72% 7.74% 58.01% 30.24% 6.37% 5.38% if we looked at a longer period (Kaye et al., 2009). In addition, this study is limited to those who were poor and covered by Medicaid to begin with, not those who became poor enough to be eligible to Medicaid given their use of LTC. 4. DISCUSSION We find that, on average, greater home care use among those already eligible for Medicaid home care appears to reduce the likelihood of a nursing home stay and to reduce the number of days in a nursing home among those who do enter a nursing home. Although the results of our analyses consistently suggest that Medicaidfunded home care helps to reduce nursing home use, we find that the cost offsets to Medicaid of expanding home care to those receiving it are only partial. Although the data allow us to precisely identify total days of institutional care and the costs of Medicaid-paid home care services used by people, the lack of data on any payments for institutional care by Medicare and other payers is likely to undervalue the total cost offsets. To obtain a sense of the potential magnitude of the underestimate, the results on institutional care utilization could be used to proxy the total cost offsets. If we use the 2005 national daily average nursing home rate of $203 (The MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2005) and apply that to our estimated reduction in nursing facility use of 2.75 days per year, the total cost saving on nursing home services is about $558 per year for a $1000 increase in Medicaid home care expenditures. The estimated cost savings on institutional care for greater Medicaid home care spending are potentially consistent with previous findings that used different approaches to estimate cost offsets. Muramatsu et al. (2007) suggested that doubling state-level Medicaid HCBS expenditures would reduce the risk of future nursing home entry by 35% among childless seniors, but no significant effect was found among seniors with living children. Van Houtven and Norton (2008) found that a 10% increase in informal care hours provided by children reduced annual Medicare skilled nursing expenditures by $25 among single elderly. Dale and Brown (2006)’s study based on an Arkansas sample in a 3-year study period suggested that a reduction in nursing facility use induced by consumer-directed home care did not fully offset the higher home care costs of new home care users, but for the group that was already getting home care at the time that they enrolled in CCDE, the decrease in nursing home costs more than offsets the higher cost of the HCBS. Although we test a different research question in our study— the extent to which additional home care spending was offset by reduced institutional spending, not whether Cash and Counseling led to reductions in institutional spending—our results are generally consistent. Given the current policy trend of expanding Medicaid home care services, there is a serious need to understand how we might best allocate public funds across home care and nursing home care to meet the growing LTC needs of an aging population. To fully answer this question requires evidence about both outcomes and costs. Our findings suggest a complex scenario that expanding Medicaid-financed home care services might be a potential cost-effective but not cost-saving approach to delivering LTC because it does significantly substitute for nursing home services, yet the offset is only partial. This suggests that further evidence on the benefits provided by home care would be helpful in gauging the cost-effectiveness of further investments in home care. Costs and benefits to caregivers are another missing piece. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE ON INSTITUTIONAL LTC 15 Extrapolating our results to the utilization and cost trade-offs that would result from future expansions of HCBS depends on the form and extent of expansion. Because our estimates are based on additional home care costs among already eligible individuals, they are likely most applicable to the cases in which states expand Medicaid funding for existing home care programs, perhaps increasing supply through programs that allow the hiring of family and friends, without changing eligibility. However, states may expand HCBS through a variety of mechanisms. If expansion takes the form of loosening eligibility requirements such that a greater number of people are served, then the ‘marginal’ person receiving home care is likely to be healthier and less likely to need nursing home care. This is consistent with a potential ‘woodwork effect’ in which individuals who would not have received home care under prior policies are drawn into the program because of more attractive benefits and eligibility criteria. In this case, our estimates of the reduction in nursing home use and costs resulting from more home care are likely to be too high. On the other hand, HCBS expansions that target sicker individuals more likely to use nursing homes may see a greater substitution than our estimates imply, such as the initial findings from Money Follows the Person demonstration (Bohl et al., 2014). Finding a way to appropriately target the correct individuals—those who will benefit most from home care relative to other sites of care—is a key policy challenge faced by state Medicaid programs, one that our estimates cannot solve. With the aging of the population in the USA and in Europe, the demand for LTC is likely to grow in coming decades. Even beyond appropriate targeting of home care, the broader policy challenge is how to allocate scarce LTC resources to best meet this demand, a demand that is also characterized by considerable uncertainty in terms of the future prevalence, care needs, and technological innovation associated with specific diseases. The desirability of expanding HCBS is often taken as self-evident and probably is to some degree, but the appropriate balance between spending on HCBS and on institutional care is unknown and involves multiple trade-offs. Expanding current spending on HCBS may be beneficial, but even if well targeted toward those who can best substitute home care for nursing home care, very little is known about the non-financial benefits of HCBS, and they are likely to be heterogeneous. Recent studies (Wolff et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2014, 2015) suggest that LTC preferences depend significantly on the degree of impairment. We might also assume that the benefits of HCBS depend significantly on the home environment and informal supports. In addition, if funding for HCBS is diverted from funding for nursing homes, a setting that the most vulnerable of LTC recipients will likely still need, the quality of nursing home care may be affected. This trade-off between funding of institutional care and HCBS is further complicated by the aging capital stock of the nursing home industry; investing in upgrading of the nursing home stock may require considerable resources that would hamper funding for HCBS in the short run and perpetuate the incentive to fill nursing home beds in the long run. Although a comprehensive, rigorous analysis formally taking all these factors into account is unlikely to be feasible, these potential trade-offs should be considered by policy makers when deciding whether, and how, to expand HCBS. Within the context of these broader policy challenges, this paper contributes to the literature in that we produce causal estimates of the substitution between home care and institutional LTC use and costs. Using a unique IV from a randomized experiment, our findings are not likely to be biased by endogeneity issues, which flawed previous studies. In deciding when and how the LTC needs of an aging population may best be met, it is difficult to assess essential trade-offs without causal evidence. The policy debate would benefit from future research that rigorously explores the heterogeneity of this substitution effect and of the non-financial benefits of HCBS so that the trade-offs involved in investing in one type of care or another can be more fully evaluated. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec 16 J. GUO ET AL. REFERENCES Bohl A, Schurrer J, Lim W, Irvin CV. 2014. The changing medical and long-term care expenditures of people who transition from institutional care to home-and community-based services. http://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-programinformation/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/downloads/mfp-field-reports-2015.pdf Bound J, Jaeger D, Baker R. 1995. Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association 90: 443–450. Brown R, Carlson B, Dale S, Foster L et al. 2007. Cash and counseling: improving the lives of Medicaid beneficiaries who need personal care or home- and community-based services (No. 5583). Mathematica Policy Research Inc. Report. Charles K, Sevak P. 2005. Can family caregiving substitute for nursing home care? Journal of Health Economics 24: 1174–1190. Dale S, Brown R. 2006. Reducing nursing home use through consumer-directed care. Medical Care 44: 760–767. Dale S, Brown R. 2007a. How does cash and counseling affect costs? Health Services Research 42: 488–509. Dale S, Brown R. 2007b. The research design and methodological issues for the Cash and Counseling evaluation. Health Services Research 42: 414–445. Doty P, Mahoney K, Simon-Rusinowitz L. 2007. Designing the Cash and Counseling Demonstration and Evaluation. Health Services Research 42: 378–396. Efron B. 1987. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association 82: 171–185. Eiken S, Sredl K, Gold L, Kasten J, Burwell B, Saucier P. 2014. Medicaid expenditures for long-term services and supports in FFY 2012. http://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/ downloads/ltss-expenditures-2012.pdf Fleming T, Harrington D. 1991. Counting Processes and Survival Analysis. Wiley: New York. Garrido M, Deb P, Burgess J, Penrod J. 2012. Choosing models for health care cost analyses: issues of nonlinearity and endogeneity. Health Services Research 47: 2377–2397. Gerace A. 2012. Reposition or wrecking ball: combatting obsolescence in aged nursing home stock. Senior Housing News, http://seniorhousingnews.com/2012/10/24/reposition-or-wrecking-ball-combatting-obsolescence-in-aged-nursinghome-stock/ Guo J, Konetzka RT, Dale W. 2014. Using time trade-off methods to assess preferences over health care delivery options: a feasibility study. Value in Health 17: 302–305. Guo J, Konetzka RT, Magett E, Dale W. 2015. Quantifying long term care preferences. Medical Decision Making 35: 106–113. Heckman J, Robb Jr. R. 1985. Alternative methods for evaluating the impact of interventions: an overview. Journal of Econometrics 30: 239–267. Imbens G, Angrist J. 1994. Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica 62: 467–475. Jette AM, Tennstedt R, Crawford S. 1995. How does formal and informal community care affect nursing home use? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 50: S4–S12. Kaye H, LaPlante M, Harrington C. 2009. Do noninstitutional long-term care services reduce Medicaid spending? Health Affairs 28: 262–272. Kemper P, Applebaum R, Harrigan M. 1986. Community care demonstrations: what have we learned? Health Care Financing Review 8: 87–100. Kemper P. 1988. The evaluation of the National Long Term Care Demonstration. 10. Overview of the findings, Health Services Research 23: 161–174. Konetzka RT, Karon S, Potter D. 2012. Users of Medicaid home and community-based services are especially vulnerable to costly avoidable hospital admissions. Health Affairs 31: 1167–1175. Lo Sasso A, Johnson R. 2002. Does informal care from adult children reduce nursing home admissions for the elderly? Inquiry 39: 279–297. McCullagh P, Nelder J. 1989. Generalized Linear Models (2nd edn), Chapman and Hall: London. Muramatsu N, Yin H, Campbell R, Hoyer R, Jacob M, Ross C. 2007. Risk of nursing home admission among older Americans: does states’ spending on home- and community-based services matter? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 62: S169–S178. Newey W, Powell J, Vella F. 1999. Nonparametric estimation of triangular simultaneous equations models. Econometrica 67: 565–603. Newman SJ, Struyk R, Wright P, Rice M. 1990. Overwhelming odds: caregiving and the risk of institutionalization. Journal of Gerontology 45: S173–S183. Ng T, Harrington C, Musumeci M, Reaves EL. 2014. Medicaid home and community-based services programs: 2010 data update. Menlo Park (CA): The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Available from: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation. files.wordpress.com/2014/03/7720-07-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-programs_2010-data-update1.pdf Spillman BC, Pezzin LE. 2000. Potential and active family caregivers: changing networks and the ‘sandwich generation’. Milbank Quarterly 78: 347–374. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec CAUSAL EFFECTS OF HOME CARE ON INSTITUTIONAL LTC 17 Staiger D, Stock J. 1997. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 65: 557–586. Terza J, Basu A, Rathouz P. 2008. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. Journal of Health Economics 27: 531. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2012. Growth in Medicaid long-term care services expenditures, FFY 1990–2009. Kaiser Slides, http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?ch=476 The MetLife Mature Market Institute. 2005. The MetLife Market Survey of Nursing Home and Home Care Costs. Westport, CT. Van Houtven C, Norton E. 2004. Informal care and health care use of older adults. Journal of Health Economics 23: 1159–1180. Van Houtven C, Norton E. 2008. Informal care and Medicare expenditures: testing for heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Health Economics 27: 134–156. Wolff JL, Kasper JD, Shore AD. 2008. Long-term care preferences among older adults: a moving target? Journal of Aging & Social Policy 20: 182–200. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Health Econ. 24(Suppl. 1): 4–17 (2015) DOI: 10.1002/hec