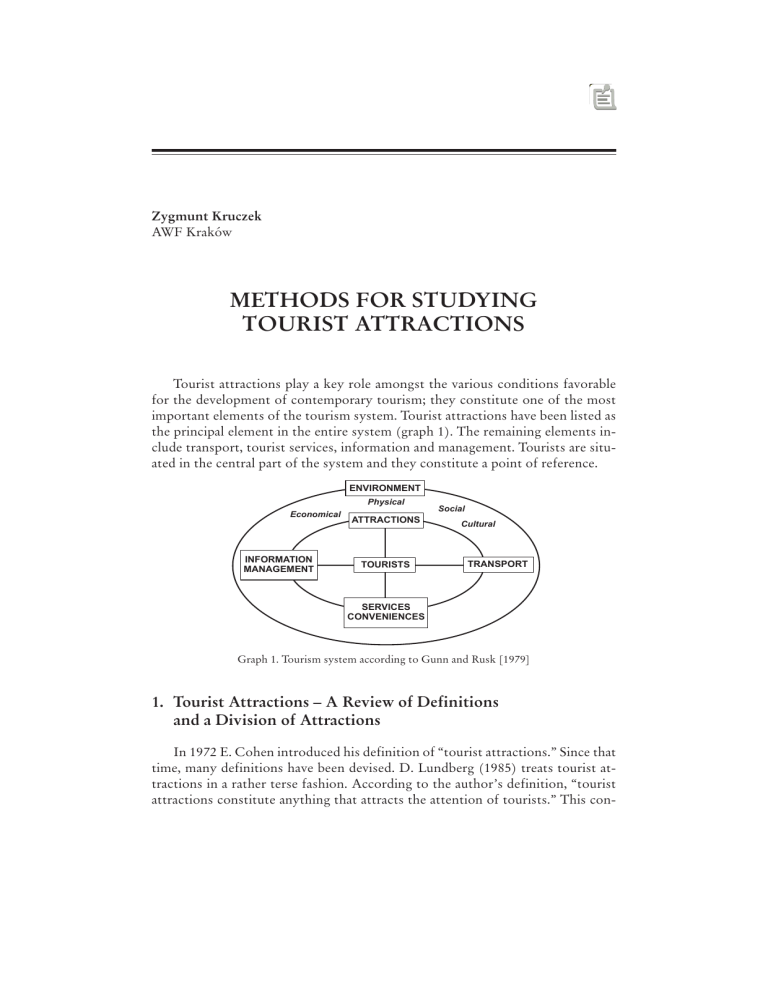

Zygmunt Kruczek AWF Kraków METHODS FOR STUDYING TOURIST ATTRACTIONS Tourist attractions play a key role amongst the various conditions favorable for the development of contemporary tourism; they constitute one of the most important elements of the tourism system. Tourist attractions have been listed as the principal element in the entire system (graph 1). The remaining elements include transport, tourist services, information and management. Tourists are situated in the central part of the system and they constitute a point of reference. ENVIRONMENT Physical Economical INFORMATION MANAGEMENT ATTRACTIONS TOURISTS Social Cultural TRANSPORT SERVICES CONVENIENCES Graph 1. Tourism system according to Gunn and Rusk [1979] 1. Tourist Attractions – A Review of Definitions and a Division of Attractions In 1972 E. Cohen introduced his definition of “tourist attractions.” Since that time, many definitions have been devised. D. Lundberg (1985) treats tourist attractions in a rather terse fashion. According to the author’s definition, “tourist attractions constitute anything that attracts the attention of tourists.” This con- Zygmunt Kruczek 34 cise definition of tourist attraction resembles the Polish definition of “sightseeing value.” B. Goodall uses a descriptive definition of tourist attractions, saying they are “characteristic, often unique sights such as the natural environment, historical landmarks, or festivals and sport events”. Obviously, the definition of “tourist attractions” is vast and includes other important elements, such as the level of prices, local residents’ attitude toward tourism and tourists, and the entire technical infrastructure including tourist facilities (Podemski 2004). Similarly, A. Lew describes tourist attractions by claiming that “they comprise all elements which persuade tourists to leave home.” The above–mentioned elements include the landscape, interesting forms of transport, accommodation, restaurants as well as conditions favorable for practicing various forms of activities, and related experiences. D. McCannell’s systems approach (2002) contributes a great deal to the discussion about the essence of tourist attractions. According to the author, a tourist attraction can be expressed as a relation between tourist, sight and marker. The last element pertains to the information about a certain place. This empirical relation is presented in the scheme below: Tourist –> sight Marker –> ATTRACTION An object (sight) acquires the character of an attraction after a marker is added. Markers have diversified ways of assembling information, such as guides, information plates, slides, reports etc. The promotion of an object could be perceived as the marker’s role. We should keep in mind that factors like promotion and advertisement are constantly generating new attractions. The marker plays an essential role; we would be unable to distinguish famous landmarks if they were not marked. Paraphrasing this statement, a layman would not be able to tell whether a rock was brought back from the moon or if it was just an ordinary rock from Earth. J. Swarbrooke (1995) proposed that we distinguish four groups of attractions: – Natural tourist attractions, – Man–made objects created for purposes other than attracting tourists; in time they become attractions in themselves, – Sights constructed from the beginning as attractions, – Cultural events, sport events, religious events, festivals, the Olympic Games etc. J. Swarbrooke also devised a more simplified classification. He distinguished between basic attractions (the main reason why we make a journey and spend most of our time there) and secondary attractions, which are treated as attrac- Methods for studying tourist attractions 35 tions encountered on the way. Attractions can be also classified in terms of the proprietor, range and number of visitors, location, size, the potential client and his expectations. 2. Review of Tourist Attraction Studies Until the 1990s the definition of tourist attractions did not appear in Polish scientific literature. So far, only a few studies have been written on this subject; mostly they deal with the essence and quality of tourist attractions. As for tourism research, many disciplines are concerned with tourist attractions. They are studied by representatives of the social sciences i.e. psychologists and sociologists, as well as by representatives of economics and spatial studies. The methods in tourist attraction research involve various types of evaluations. These include ranking lists, distribution and evaluation analyses (performed by geographers), marketing studies (including surveys of the tourist attraction market), and behavioral research (the reception of an attraction, analyses of what people experience when visiting an attraction). Scientists have also attempted to assess the quality of tourist attractions, perceiving them as the nucleus of a tourist product. Studies on tourist attractions employ different scales, such as the Likert Scale, the Scottish Attraction Questionnaire etc. In Poland, M. Nowacki has most frequently studied the problem of tourist attractions (2000, 2002, 2003). Among other scientists interested in this subject we should mention Z. Kruczek (2202), K. Podemski (2004) and K. Kozuchowski (2005), as well as a research group from the Warsaw Tourism Institute (M. Byszewska, L. Kulesza 2004). 2.1 The Evaluation of an Attraction’s Reception (Behavioral Methods) Semantic Differentiation Test This method is frequently used in marketing studies. It is used to construct semantic profiles and can be applied if we wish to obtain the consumers’/tourists’ opinion concerning the features of the product. This method selecting from opposite pairs to describe the product’s characteristics. The pairs are as follows: pretty – ugly, comfortable – uncomfortable, clean – dirty, safe – dangerous, attractive – unattractive, cheap – expensive, distant – close etc. Respondents are asked to rate the product on a scale according to their responses. The scale is made up of evenly distributed numbers (followed by negative and positive signs), which correspond to the perception of the product (either bad or good). This method can also be applied to determine tourists’ feelings toward a tourist product, or even a region, city or facility. Zygmunt Kruczek 36 It is also possible to construct a semantic profile based on the assessment of various features of a tourist product. These features include standard and size of accommodation, diversity of recreational infrastructure, quality of service staff, local residents’ attitudes toward tourists etc. In this way we are able to obtain information regarding tourists’ feelings (e.g. different nationalities) or information pertaining to the standard of service offered, as viewed by tourists and experts. This procedure enables us to evaluate the product’s image and mark out the course for improving its development (Z. Kruczek, B. Walas 2004). Graph 2. Semantic profile Studies on Satisfaction The experts recommend taking surveys of visitors’ satisfaction and conducting detailed analyses of their expectations and sensations. Norwegian scientists conducted research on tourist experiences using the “instrumental perspective” (J. Vitterso, M. Vorkinn, O. Vistand, J. Vaagland 2000). In these studies satisfaction was perceived as the result of comparing something we anticipate and something we experience in reality. Satisfaction is regarded as a cognitive process that leads to a specific emotional state. This emotional state may be the effect of a product’s interaction, as well as interaction through an experience. However, we will encounter problems when measuring the level of satisfaction. For instance, it is difficult to eliminate negative emotions, which consequently affect the evaluation process of a specific attraction. To solve this problem various dissonance strategies have been employed. They enable us to decrease the negative differences between expectations and the final result. According to J. Festinger’s dissonance theory (introduced in 1972), there exist two contrary cognitive elements, which create discomfort and consequently motivate people to restore a certain state of harmony. Methods for studying tourist attractions 37 If we assume that satisfaction is the result of a cognitive process (despite possible dissonances), we still have to determine what the basis for comparison is. There are four possible answers. The tourist evaluates a given attraction according to the ideal standard (how could it be), to a comparative standard (how should it be), a minimal standard (how it has to be), and according to one’s own expectations (how will it be). Satisfaction studies should employ various models depending on the phase of the journey: processes prior to the journey; arrival to destination; and after the journey. Many authors concur that the flow theory proposed by Csinkszentmihaly is quite useful in identifying tourist and recreational sensations. The term “sensations” relates to the entire spectrum of subjective experiences observed by tourist e.g. evaluation, preferences, humor, and emotions. The flow theory was elaborated and applied for the first time in Norway with a sample of six national tourist attractions (e.g. exhibitions, museums and the writer’s home). 2.2. Marketing Studies on Attractions ASEB/SWOT Analysis The ASEB/SWOT analysis method proposed by R.C. Prentice (1995) represents a developed version of the traditional SWOT analysis and constitutes a crucial element in the strategic business planning process and Manning and Haas requirement system. The above–mentioned method was elaborated in order to stimulate the development and promotion of managed tourist attractions such as museums. This method is designed to facilitate the management of client–friendly department. It focuses on the needs, motives and sensations of the visitors. Subsequently, this leads to a situation in which a tourist claims he is satisfied and desires to visit this destination again. Prentice postulated that the classical SWOT analysis should be supplemented with an extra dimension – levels of hierarchy requirements. Such an expanded analysis aims at highlighting the needs of a person visiting a museum. The thesis of behavioral sciences introduced by Manning & Hass states that “people undertake certain actions in order to satisfy their needs and accomplish certain goals” (1986, p. 232). Subsequently, this theory was supplemented by distinguishing four hierarchic expectation levels in terms of leisure activity: level one – form of the activity; level two – the place where this activity is carried out; level three – experiences and sensations resulting from the activity and associated with its environs; level four – benefits from that activity. The significance of the listed levels is presented below (R. C. Prentice 1995): – Level one is identified with the requirements that apply during a visit to a museum. This includes the various forms of activities offered at the muse- Zygmunt Kruczek 38 – – – um, specific motives which persuade someone to visit the museum, and the feeling of satisfaction which can be experienced by participating in this type of activity, Level two signifies the context in which a given activity takes place (environmental, social and organizational). It also deals with visitors’ expectations toward the place of the activity itself, Level three is associated with experiences, in other words, what the tourist feels when he participates in a certain activity in a certain place. This includes thoughts, sensations, feelings, reactions etc., Level four is associated with various social or psychological benefits that result from participating in a given activity. 2.3. Selected Study Techniques The Scottish Questionnaire for Evaluating an Attraction These studies employ “participating observation.” The results of the observation are registered as coded grades on a special evaluation form. The Scottish Tourist Board introduced a form for evaluating tourist attractions, which comprises six principle elements pertaining to the attraction: admission, entrance, topic presentation, catering, stores, and restrooms. The above–mentioned elements are evaluated according to an 11–grade scale (from 0 to 10). For each principal element the average values have been calculated. The average grade calculated for the six principal elements constitutes the ultimate grade value (named AT). In the final phase of the evaluation each attraction was assigned a specific category. Authors employed a four–level scale: 0 – unacceptable quality (no stars); 1 – acceptable quality with numerous remarks (*); 2 – acceptable quality with minor remarks (**); 3 – excellent quality, no remarks (***). M. Nowacki (2002) employed this method to analyze and evaluate 23 tourist attractions in the central– western region of Poland. In order to increase the credibility of the grades obtained, the author decided to evaluate each attraction by utilizing a few independent groups. The final result was the average of all the grades. SERVQUAL questionnaire in studies conducted by M. Nowacki In 1990 A. Parasuraman devised a scale for measuring service quality. The author assumed that satisfaction in service quality can be defined “as the difference between a client’s expectations for this quality and its perception.” Consumers’ expectations are conditioned by oral information, personal needs, past experiences and trade information. The authors of this scale managed to identify several discrepancies encountered in the relation chain between the consumer and the service Methods for studying tourist attractions 39 personnel. Such scales were applied to evaluate the quality of hotel services, travel agencies or regions. M. Nowacki (2002) has adjusted the aforementioned scale for his studies. The studies were carried out in the palace and park complex in Rogalin (Western Poland). A group of 102 respondents was selected. Nowacki used both methods: the Serqual method and the Scottish questionnaire. 2.4. Methods for Studying the Quality of Tourist Attractions Nowacki’s Sensation Grades for the Reception of an Attraction The studies on the sensations associated with tourist attractions employ the “Recreation Opportunity Spectrum” (ROS). This spectrum features a series of mutually determined and recurrent events, i.e. a certain activity performed in certain conditions during which a person experiences certain sensations and subsequently obtains certain benefits. The authors list the following sensations: delight of nature, escaping physical stress, learning, sharing common values, and creativity. Some authors also include “unique atmosphere” among the benefits. Many authors emphasize the usefulness of the flow theory (introduced by Csinkszentmihaly) in identifying tourist and recreational sensations. According to Csinkszentmihaly, the main feature of a successful experience is that it represents a goal in itself. This experience is usually accompanied by profound satisfaction and a sense of excitement. The “flow” phenomenon relates to the optimal state of internal experiences, which are characterized by the following qualities: focusing on a current task, comprehensive involvement of one’s consciousness and the ability to use one’s skills, losing one’s self–consciousness and losing the sense of time passing, and most importantly, the prevalence of autothelic experiences. In his research M. Nowacki (2003) selected the phenomenological approach as the preliminary method. It should be noted that phenomenology does not have traditional research techniques. Phenomenological study is aimed at discovering the structure of the phenomenon. In order to accomplish this task we must study a person who is experiencing this particular phenomenon. The phenomenological approach seeks the significance of events and not their causes. The studies conducted by M. Nowacki had a qualitative character and were aimed at the preliminary reconnaissance of sensations experienced when visiting a particular tourist attraction. The studies employed an interview method, which was conducted by sophomore students majoring in tourism and recreation at the Academy of Physical Education in Poznan. The aforementioned method was carried out according to a structural plan. The respondents were asked two questions: what tourist attraction they have recently visited, and if they could describe their sensations during this visit. In the final part of the interview respondents were asked whether their sensations had been authentic. 40 Zygmunt Kruczek This analysis enabled the distinguishing of 11 sensation groups when visiting a tourist attraction. Here is the list of these sensations: educational, esthetic, romantic and emotional, retrospective, relaxing, social interactions, fun, active recreation, introspection, contemplation, and escape. In addition we should mention sensations associated with shopping, collecting souvenirs and penetrating the terrain. 2.5. Methods for Evaluating the Value of Tourist Attractions Tourism organizers require highly acclaimed attractions in order to create valuable tourist offers. Tour operators as well as other tourism organizers can select from a number of lists prepared by various organizations. The most recognized rankings are those that have been prepared by international organizations (e.g. UNESCO) and federal organizations (e.g. the List of Historical Monuments). Other rankings have been introduced by the media, press and acclaimed persons (e.g. a list of world’s wonders: the seven ancient wonders, and the wonders of science and technology). At present there is a fashion for creating top–100 rankings, listing the most interesting places in the world, the most attractive cities, buildings, natural landmarks etc. Such lists are very important in terms of promoting the destinations where these attractions can be found. They also act as a sort of guide for contemporary tourists; they are inclined to visit places that are highly recommended by acclaimed persons. Below is a list of rankings used most frequently in the tourist industry: Featured Rankings UNESCO World Heritage List This is the most prestigious and recognized list in the world. Tourists acknowledge places mentioned on this list as attractions simply because they have been listed here. In this case cultural and natural values are not taken into account. The list was created in 1978 and currently is comprised of 812 objects in 137 countries (including 628 cultural, 160 natural and 24 mixed). Being registered on the UNESCO list has a tremendous promotional impact; usually the number of tourists increases because people wish to visit recently registered places. The List of Poland’s Historical Monuments The most precious and interesting landmarks from the past were registered on the “List of Historical Monuments.” The President of the Republic of Poland signed this list in 1995. Subsequently, the list has been supplemented three times (2000, 2002, 2005), and currently features 27 monuments. This list partially cor- Methods for studying tourist attractions 41 responds with the UNESCO list. The latter list currently features 12 sites on Polish territory. It is valuable to be registered on this list because it generates promotion for the local proprietors of tourist facilities. The UNESCO Biosphere Reserves List In 1970 UNESCO created a global net of biosphere reserves, which are comprised of the most valuable regions from an educational and scientific point of view. In Poland, seven national parks were registered on that list: Babiogórski, Białowieski, Bieszczadzki, Karkonoski, Kampinoski, Słowiński, and Tatra. The list also mentions Luknajno Lake Reserve and the Western Polesie Region. Large Sightseeing Centers in Poland Sightseeing centers are large cities (or groups of cities closely related both functionally and spatially), which are the subject of high tourist interest due to the large number of sightseeing opportunities as well as the character of urban atmosphere, demonstrated in the high standard of shopping and entertainment services. In Poland there are 10 large sightseeing centers, which are divided into four groups, based on their similarities as tourist areas. The proposed centers spurred the introduction of new criteria. For example, the Ministry of Labor requires that a local guide be hired in several large cities. Ranking the Frequency of Visits to Tourist Attractions The criterion for the attraction’s significance can be expressed as the tourists’ impact measured in the number of people who visit a given attraction. Renowned sites are visited by millions of tourists every year. In Vienna 8 million tourists visit the Schonbrunn Castle (4 million the park, 1.8 million the castle, and 2 million the zoo) and 9 million tourists every year visit the Cologne Cathedral (estimates, entrance tickets excluded). In Poland 900,000 people visit the Wieliczka Salt Mine annually and over a million people tour the Wawel Castle Exhibition. The Tatra Mountain National Park is visited by nearly three million people. Over six million tourists visit the Louvre Museum (the most visited museum in the world). The Great Smoky Mountains and Eurodisneyland (located near Paris) are both visited by nearly 10 million people. Conclusions The current tourist attraction analysis methods are based either on social sciences methodological workshops (behavioral methods) or associated with marketing methods. In my opinion, it is possible to combine both approaches into an integrated study procedure. 42 Zygmunt Kruczek Studies on tourist attractions possess not only a theoretical aspect but also a practical aspect (i.e. the market). The absence of an objective and up–to–date evaluation hinders maintenance of a high standard of services. Consequently, the absence of comprehensive promotion and updated information on services leads to misunderstandings and lowers the visitors’ satisfaction. Lack of interest and the boredom that accompanies sightseeing is the result of the existing discrepancies between clients’ expectations and the services offered during a sightseeing tour. These drawbacks are primarily caused by the lack of consciousness, knowledge and managerial policies in the management of the attractions, and adequate studies and analyses. References Alejziak W., Winiarski R. 2003. Perspektywy rozwoju nauk o turystyce [Perspectives of Tourism Sciences Development]. [in:] R. Winiarski (red.); Nauki o turystyce. Studia i Monografie AWF 7, wyd. 2, Kraków, Cohen E. 1972. Towards a Sociology of International Tourism. “Social Research”, 39:164–182. Byszewska-Dawidek M., Kulesza I. 2004. Krajowy rynek atrakcji turystycznych [Domestic Market of Tourist Attractions]. Instytut Turystyki, Warszawa (typescript). Festinger J. 1972. An Introduction to the Theory of Dissonance. [in:] Classic Contributions to Social Psychology. Readings with Commentary, E. P. Hollander and R. G. Hunt, eds., Oxford University Press., London, pp. 209– 219. Goodall B. 1990. The Dynamics of Tourism Place Marketing. [in:] G. Ashworth i B. Goodall (red): Marketing Tourism Places, Routledge, London. Gunn S., Rusk C.A. 1979. Tourism Planning, Crane, Russak and O., New York, Hughes K. 1991. Tourist Satisfaction: a Guided “Cultural” Tour in North Queensland. Australian Psychologist 26:166–171 Kożuchowski K. 2005. Walory przyrodnicze w turystyce i rekreacji [Natural Values in Tourism and Recreation]. Wydawnictwo Kurpisz, Poznań. Kruczek Z. 2002. Atrakcje turystyczne. Metody oceny ich odbioru – interpretacja [Tourist Attractions. Evaluation and Reception Methods – An Interpretation]. Folia Turistica 13; pp. 37 – 61. Kruczek Z. 2005. Polska. Geografia atrakcji turystycznych [Poland. The Geography of Tourist Attractions]. Proksenia, Kraków. Kruczek Z., Walas B. 2004. Promocja i informacja turystyczna [Tourist Promotion and Information]. Proksenia, Kraków. Methods for studying tourist attractions 43 Leiper N. 1990. Tourist Attraction Systems. Annals of Tourism Research, 17: 367– 384. Lew A. 1987. A Framework of Tourist Attraction Research. Annals of Tourism Research, 14 (4): 533–575. Lundberg D. 1985. The Tourist Business. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York. Manning R.E. 1986. Studies in Outdoor Recreation. A Review and Synthesis of the Social Science Literature in Outdoor Recreation, Cornvallis, Oregon, Oregon State University Press. Macbeth J. 1982. Studies of Flow: Activity vs. Life Style in Sailing. [in:] Proceedings of the VII Commonwealth and International Conference, 9 Socio– Historical Perspectives. Brisbane. McCannel D. 2002. Turysta. Nowa teoria klasy próżniaczej [The Tourist. A New Theory on an Idle Class]. Wyd. Literackie Muza S.A. Warszawa. Nowacki M. 2002. Ocena jakości produktu atrakcji turystycznej z wykorzystaniem metody Serqual [Evaluation of the Quality of Tourist Attraction Products Employing the Serqual Method]. Turyzm, 12/1 Nowacki M. 1999. Atrakcje turystyczne, dziedzictwo i jego interpretacja – jako produkt turystyczny [Tourist Attractions, Heritage and its Interpretation – as a Tourist Product], Problemy Turystyki, t. XXII, 2: 5–12. Nowacki M. 2000. Rola interpretacji dziedzictwa w zarządzania atrakcjami turystycznymi [The Role of Heritage Interpretation in Tourist Attraction Management]. Problemy Turystyki, t. XXIII, 3–4: 35–47. Nowacki M. 2003. Wrażenia osób zwiedzających atrakcje turystyczne [Sensations of People Visiting Tourist Attractions], Folia Turistica 14, M. Nowacki. 2000. Analiza potencjału atrakcji krajoznawczych na przykładzie Muzeum Narodowego w Szreniawie [Analysis of the potential of sightseeing attractions. Example from the Szreniawa National Museum] . [in:] Przemysł Turystyczny. Politechnika Koszalińska. Parasuraman A., Zeithaml V., Berry L. 1990. Delivering Quality Service, Free Press, New York. Podemski K. 2004. Socjologia podróży [The Sociology of Travel]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań 2004 Prentice R.C. 1994. Perceptual Deterrents to Visiting Museums and Other Heritage Attractions. Museum Management and Curatorship, 13: 264– 279. Prentice R. C. 1995. Evaluating the Experiences and Benefits Gained by Tourists Visiting. A Socio– Industrial Heritage Museum: An Application of ASEB Grid Analysis to Blists Hill Open Air Museum. The Ironbridge Gorge Museum, United Kingdom. Museum Management and Curatorship , 14 (4): 229– 251. Prentice R. C. 1996. Tourism as Experience. Tourists as Consumers. Insight and Enlightenment. Edinburgh QMC. 44 Zygmunt Kruczek Richards B. 2004. Marketing atrakcji turystycznych [The Marketing of Tourist Attractions]. Pearson Longan. Polska Organizacja Turczyna, Warszawa. Pytlarz E. 1999. Przyszłość przeszłości – analiza atrakcyjności wystaw typu Jorvik Viking Center w Polsce [The Future of the Past – The Analysis of Exhibitions Presented by the Jorvik Viking Center in Poland, [in:] Marketing turystyki. AVSI oraz Instytut Turystyki w Krakowie. Ritchie J. R., Sins M. 1978. Culture as Determinant of the Attractiveness. Annals of Tourism Research, April – June. Swarbrooke J. 1995. The Development and Management of Visitors Attractions, Butterworth–Heinemann, Oxford. Van Raaij W.F. 1986. Expectations, Actual Experience, and Satisfaction. A Reply. Annals of Tourism Research 14:141–142. Visitor Attractions Inspection Scheme. 1995. Criteria and Application Form. Edinburgh Scottish Tourist Board. Vitterso J., Vorkinn M., Vistad O.I., Vaagland J. 2000. Tourist Experiences and Attractions, Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 27, 2: 432–450. Wall G. 1977. Tourism attractions: line, point, area. Annals of Tourism Research 24 (1):.240–243 Williams D.R. 1989. Great Expectations and the Limits to Satisfaction: A Review of Recreation and Consumer Satisfaction Research. [in:] A.E. Watson (ed.): Outdoor Recreation Benchmark 1988. Proceeding of the National Outdoor Recreation Forum, January, pp.422–438 (Tampa, FL). Wiza A. 2004. Atrakcje turystyczne w kontekście współczesnej turystyki [Tourist Attractions in the Light of Contemporary Tourism]. [in:] S. Bosiacki, J. Grell (red.): Gospodarka turystyczna w XXI w. Szanse i bariery rozwoju w warunkach integracji międzynarodowej. [red. ]. AWF, Poznań, 195 – 198.