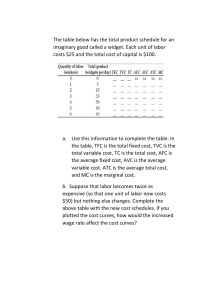

ECOM4000 Economics Topic 4 Production, Revenue and Costs 1 ECOM4000 Economics Topic 4 Production, Revenue and Costs Photo by Renee Fisher on Unsplash 1 Document Classification:Public Kaplan Business School (KBS), Australia 1 1. The Firm and Economic Profit • • • • • A firm: an economic entity that hires and organises the factors of production The goal of a firm is to make and maximise economic profit Economic profit = total revenue - total economic cost, which includes explicit + opportunity cost Economic profit is less than accounting profit because economic profit includes opportunity cost Economic profit can be negative even if accounting profit is positive When we consider production and costs: short run and the long run 2. The Product Schedule • A product schedule describes the relationship between output and the quantity of a variable input employed, usually labour: • Total product (TP) is total output produced • Average product (AP) is the average output produced AP = TP / L • Marginal product (MP) is the change in total output produced MP = ∆TP / ∆L • The principle of diminishing returns says that output will begin to increase at a decreasing rate as more and more variable inputs are used in production A short run product schedule assuming the only variable factor is labour • As the quantity of labour employed increases: • TP increases, but at a decreasing rate. • AP and MP increases initially but then eventually decreases. • TP curve is a graph of TP against labour; shows how TP changes as the quantity of labour employed in the production process increases. Typical shape: increasing at a decreasing rate. • AP curve is a graph of AP against labour; shows how AP changes as quantity of labour employed in the production process increases. Typical shape: at first increasing but then decreasing. • MP curve is a graph of MP against labour; shows how MP changes as the quantity of labour employed in the production process increases. Typical shape: at first increasing but then decreasing. (Note: coordinates of the MP curve are plotted at the midpoints of labour input) MP curve intersects the AP curve at its maximum point • When MP is above AP, AP increases; each additional unit of labour employed in production produces more and more output, pulling the AP up. • When MP is below AP, AP decreases; each additional unit of labour employed in production produces less output, dragging AP down. • When MP = AP, AP is at its maximum. The reason for this is the principle of diminishing returns. The principle of diminishing returns • The principle of diminishing returns says that as one input in production increases, while holding all other inputs constant, at some point output will begin to increase at a decreasing rate - point of diminishing returns. • The principle of diminishing returns explains the shape of all three product curves: TP, AP and MP. • If we consider just one variable input, labour, then as a firm employs more and more labour to be used with a given quantity of fixed inputs, then the MP of labour will eventually diminish. • Diminishing returns arise because employing additional labour means each worker has less access to the other (fixed) factors of production, like capital and work space. 3. The Revenue Schedule • A revenue schedule describes how revenue changes as total product changes: • Total revenue (TR) is the cash flow earned from the sale of a firm’s G&S over a given period of time. The degree to which TR changes as price changes depends on DD curve for the G&S we are talking about. TR = P x Q • Average revenue (AR) is the average revenue per unit of output sold over a given period of time. AR = TR / Q = P • Marginal revenue (MR) is the change in TR per unit of output produced over a given period of time. MR = ∆TR / ∆Q The short run revenue schedule shows how revenue changes as output changes • As the price decreases: • TR at first increases, but then decreases, because of the price elasticity of demand varying over the DD curve, and the relationship it has with TR. • AR consistently decreases and is a straight line, because DD curve iis a straight line. • MR decreases. MR is, at first, positive, meaning TR increases as output increases, but then it becomes negative, meaning TR decreases as output increases. • TR curve is a graph of TR against output, and shows how TR changes as quantity of output increases. Typical shape: an upside down U-shape, reflecting the changing PED over DD curve. • AR curve is a graph of AR against output, and shows how AR changes as quantity of output increases. Same shape as DD curve, since AR = P. • MR curve is a graph of MR against output, and shows how MR changes as quantity of output increases. Typical shape: at first positive before becoming negative. This is because of the principle of diminishing returns. If a firm faces a downward sloping DD curve; MR curve is always below DD curve • The chart on the slide shows how the MR curve is consistently below the DD curve at all levels of output. (If a firm faces a horizontal DD curve - perfect competition, then the MR curve = DD curve) • This all has important implications for market structure that we will start in the next topic. 4. The Cost Schedule • A cost schedule describes the relationship between output and the costs of production • Economies of scale refers to the situation where average total cost falls in the long run • To increase output in the short run, a firm must increase the factors of production it employs. In the short run, the firm can only increase variable factors of production and we will assume that a firm adjusts the amount of labour employed. If the firm employs more labour, then obviously the cost of production increases. But remember, in addition to the cost of the variable input labour, the firm must also pay for the cost of fixed inputs as well. • Three concepts that describe the relationship between output and the cost of production. • Total cost (TC) is the total cost of production over a given period of time. TC = TFC + TVC • Average cost (AC) is the average cost of production over a given period of time. AFC = TFC / Q ; AVC = TVC / Q ; ATC = TC / Q = AFC + AVQ • Marginal cost (MC) is the change in the total cost of production, over a given period of time. MC = ∆TC / ∆Q The short run cost schedule assuming the only variable factor is labour • The table on the slide reports the cost schedules for TC, AC and MC for various output levels. We are assuming that the cost of labour is $50 per worker. • TC curve is a graph of TC against total product • TVC is the cost of all variable resources used in production. VCs do change with output – this is why the TVC curve increases. • TFC is the cost of all fixed resources used in production. FCs do not change with output – this is why the TFC curve is horizontal. • TC is the cost of all resources used in production, both variable and fixed. TC curve = TVC + TFC curves. So the vertical distance between the TC and TVC curves is equal to TFC. • AC curve is a graph of AC against total product • AVC is TVC per unit of output. Typical shape: at first decreasing but then increasing. This is because of diminishing returns. • AFC is total FC per unit of output. FC do not change with output, the AFC curve declines. • ATC is TC per unit of output. Typical shape: at first decreasing but then increasing, because of diminishing returns. The vertical distance/difference between ATC and AVC is AFC. • MC curve is a graph of MC against total product • MC is the increase in TC that results from a one unit increase in total product. The MC curve shown on the slide has a typical shape. • There is an important relationship between the MC and MP curves: • Over the output range with increasing MP, MC decreases. • Over the output range with decreasing MP, MC increases. MC curve intersects the ATC and AVC curves at their minimum points • MC curve intersects the AVC and ATC curves at their minimum points. This can be seen in the chart shown on the slide. • The key relationships between AVC and ATC, and MC are: • When MC is below AVC and ATC, AVC and ATC decrease. When MC is below AVC and ATC, each additional unit of output produced, on average, costs less and less, pulling the AVC and ATC down. • When MC is above AVC and ATC, AVC and ATC increase. When MC is above AVC and ATC, each additional unit of output produced, on average, costs more and more, pulling the AVC and ATC up. • When MC curve intersects the AVC and ATC curves, AVC and ATC are at their minimums. • The reason for this is the principle of diminishing returns. These relationships are the “cost version” of the relationship we have already seen between the MP and AP curves. When the marginal product curve is rising, the marginal cost curve is falling • The principle of diminishing returns implies there is a relationship between MP and MC: • When MP is rising, MC is falling and • When MP is falling, MC is rising. • And because of this, the MC curve is a “mirror image” of the MP curve. • The principle of diminishing returns also implies there is a relationship between AP and AVC: • When AP is rising, AVC is falling and • When AP is falling, AVC is rising. • And because of this, the AVC curve is a “mirror image” of the AP curve. • These relationships assume that labor is the only variable factor of production, and that its price (wages) is constant. Two factors can move the cost curves • The location of a firm’s cost curves depend on two factors: • Technology. An improvement in technology shifts the ATC curve down, reflecting the greater efficiency possible in production with the improved technology. • Prices of factors of production. An increase in the price of a factor of production increases production costs and shifts the cost curves up. But the specific effect depends on whether the factor of production is variable or fixed: • An increase in a fixed cost shifts the AFC and ATC curves up, but it does not affect the AVC and MC curves. • An increase in a variable cost shifts the AVC, ATC and MC curves up, but it does not affect the AFC curve. The long run average cost curve maps out the minimum points of all possible short run ATC curves • In the short run, ATC depends on both variable and fixed factors of production. • In the long run, however, all inputs to production are variable and there are no fixed factors. • The long run average cost (LAC) curve is the cost curve for a firm in the long run, assuming all factors are variable. LAC shows the relationship between the lowest attainable average total cost and output in the long run. To maximise profit in the long run, a producer chooses the plant size that minimizes LAC - optimal plant size. The LAC curve is derived by mapping out the minimum points of all possible short run ATC curves. • As an example, the chart on the slide shows four possible short run ATC curves, each one corresponding to a different plant size. ATC1 corresponds to plant size 1, ATC2 corresponds to plant size 2, and so on. The LAC curve maps out the minimum points of each of these four short run ATC curves. The LAC curve shown is pretty lumpy, but when every possible plant size is considered (and not just four), then the LAC curve becomes a smooth line. Economies of scale can be increasing, constant or decreasing • Economies of scale: LAC decreases as output increases - it becomes cheaper, on average, to produce more output. • A firm will experience economies of scale whenever its LAC curve is downward sloping: Chart A • Constant economies of scale: LAC remains constant as output increases - cost of production is constant, on average, as the firm produces more output. • A firm will experience constant economies of scale whenever its LAC curve is horizontal: Chart B • Diseconomies of scale: LAC increases as output increases - it becomes more expensive, on average, to produce more output. • A firm will experience diseconomies of scale whenever its LAC curve is upward sloping: Chart C. 5. Market Failure and Government Intervention • Market failure occurs when a market fails to provide an outcome that maximises the welfare of society • Allocative efficiency occurs when: • All resources are put to their most efficient use • Markets are in equilibrium and • The economy is on its PPF. • So market failure occurs if the market does not achieve allocative efficiency. When markets fail, the government usually steps in to help satisfy society’s wants. • Market failure can occur because of: • Externalities. If an economic transaction has some (any) effect on another third party that is not involved in that transaction, then an externality is generated. Externalities impose social costs and social benefits on the production and consumption of G&S. • Public goods. If a consumer cannot be stopped from consuming a G&S, or forced to pay for the consumption of a G&S, then that G&S is said to be a public good. Public goods expose a market to the free rider problem and are usually provided by a government. • Factor immobility. If factors of production (especially labour and capital) cannot easily move from the production of one G&S to another, then we have factor immobility. This can lead to market failure because economic resources are prevented from being applied to their most efficient use in production. • Imperfect information. When parties to a transaction have unequal information about that transaction then the market has imperfect (or asymmetric) information. This is a problem because the party with the greater information, usually the seller, can take advantage of the other party, usually the buyer. Recall the old saying “buyer beware”. • Monopoly. As we will see in a later topic, a monopoly describes the situation where one firm supplies the entire market. A monopolist can exploit this situation and make what are called monopoly profits. • An externality refers to an (external) effect on an unrelated third party that occurs when an economic transaction is undertaken. By definition, the externality is not included in the economic cost of the transaction, and therefore the transaction is mispriced. Because the market price is incorrect, externalities contribute to market failure and are therefore a serious problem. • The externality to the unrelated third party can be negative (a cost) or positive (a benefit). • A negative externality refers to the situation where the consumption or production of a good or service provides a cost to the third party. • A positive externality refers to the situation where the consumption or production of a good or service provides a benefit to the third party. While this sounds like a good thing, it still means the market price is incorrect because it does not include this benefit. • Examples of negative externalities include: Pollution (air and water) and litter; Obesity and other health issues; Traffic congestion • Examples of positive externalities include: Education; Insurance; Investment in local infrastructure • Public goods have the following characteristics: • Non-excludability meaning everyone can consume the goods whether they pay or not. • Non-rivalry in consumption meaning consumption by one person doesn’t reduce consumption for others. • Because of all of this, there is no incentive for a market participant to supply the G&S to the market since the supplier cannot benefit from the supply (meaning make an appropriate profit). Free rider problem: consumers consume G&S, but then not pay the fair price for this consumption. • Because there is no (private) market incentive to supply these goods or services, public goods are provided by the government. There are both advantages and disadvantages to this. • Advantages include increased employment, finite resources such as water and energy can be • guaranteed and controlled and an essential service can be provided to an entire economy. • Disadvantages include higher costs are imposed on the government, which means higher taxes, possible inefficiency; public organisations are often inefficient due to diseconomies of scale and bureaucracy and political interference may also reduce the efficiency of operations. • Examples of public G&S include law enforcement and other essential services, street lighting and roads, the defence force, public parks and other spaces and public television and radio. • Governments may intervene in the market because of market failure. Typically, the government intervention attempts to overcome the failure of the market to achieve allocative efficiency. The type of government intervention depends on the source of the market failure, but actions taken by government may include: • Taxation and subsidies. Taxes increase the cost of production and subsidies lower the cost of production; can influence market incentives. • Public ownership or provision. This includes public goods or other G&S where it is not considered socially desirable or economically feasible for the private ownership of production. • Regulation. The government can simply force market participants to change behaviour by imposing regulations. This can include limiting the production or consumption of certain G&S which are deemed to cause the market failure. • Transfer payments. Payments to the unemployed, welfare recipients and others can address income inequality by redistributing income from those that might be considered rich to those that might be considered poor. Recall from earlier in the subject that the rich own factors of production and the poor do not. • Property rights. A property right confers the right to use or enjoy certain property, the right to prevent others from producing or consuming the property, and the right to sell or give the property away. The government grants property rights to protect both tangible and intangible assets. The absence of property rights is another potential cause of market failure.