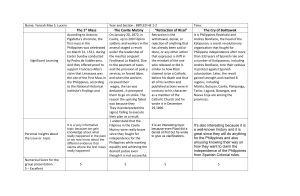

1872 CAVITE MUTINY_Draft Currently Proofreading INTRODUCTION What comes around goes around–just like chain reaction, butterfly effect and ripple effect. A small event such as a ripple in water can turn into a towering tidal wave, when given the right circumstances. This can also be applied to real life as one small event can lead to another, constantly getting bigger and more grandiose until it reaches a climax big enough to change the course of the entire history. The focus of this case study will be akin to a domino effect, diving into the importance of the 1872 Cavite Mutiny and how vital it is to Filipino History. Before all else, one must first look through the different sides of this important piece of history. The first version is from the point of view of the Filipino which was written by Dr. Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo De Tavera, a Filipino scholar and researcher. As stated by the aforementioned, the laborers in Fort San Felipe, or Cavite Arsenal, were dissatisfied by the management of Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo, who was responsible for the abolition of their work privileges. The right to be exempted from a form of tax and forced labor were the rights taken away from the arsenal workers. On January 20, 1872, around 200 laborers took up the weapons in the anticipation that their rebellion would revolutionize their existing position, however they were vanquished. Following the failed mutiny, the GomBurZa fathers were tagged as the masterminds of the Mutiny. The aforementioned was a group of influential Filipino priests who were accused of sedition and treason. They were framed for the purpose of stifling the Filipino priests who wanted more control and responsibility as opposed to being assistants. Captives from the failed mutiny were ordered to speak against the GomBurZa and they were executed through garrote on February 17, 1872. This was a public execution meant to strike fear into anyone who would want to go against the Spaniards and this event was purposely witnessed by the national hero, Jose Rizal. On the other hand, there is the Spaniard point of view written by Jose Montero y Vidal, a Spanish historian who wrote the accounts as a premeditated mutiny to overthrow the Spanish government. Gov. Gen. Rafael Izquierdo utilized these allegations to exaggerate the incident so that he could blame the Native clergy. Many other Filipino attorneys, in addition to the GomBurZa, were forbidden from delivering justice as they were jailed and sentenced to life in prison. These are the two sides of the story regarding the 1872 Cavite Mutiny but where does its importance lie within Filipino history? Everything correlates, in a sense. The GomBurZa would not have been martyred if the unfortunate Cavite Mutiny had not occurred. As a result, Jose Rizal, the Philippines' National Hero, would not have witnessed their execution and would not have written his influential books, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, which later sparked patriotism and prompted the 1896 Philippine Revolution. Despite the massive importance of the Cavite Mutiny there are a few problems that are present within the case, one of which is that the 1872 Cavite mutiny is not a common knowledge or widespread among the citizens. Thus, its significance is easily overlooked. Another complication is that there are two histories to evaluate, both of which are from competing perspectives. These problems can be eliminated through educating the public extensively. In addition to that, a comprehensive summary must be formed that should be presented alongside the original Filipino and Spanish version. These solutions can better help the public understand what was essentially the first domino piece that led to the Philippine Revolution. BODY FILIPINO VERSION This account was written by Dr. Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo De Tavera. He was a Filipino historian and a physician who founded the Federal Party and served on the Philippine Commission. In addition to being a superb scholar, he was a bibliophile and bibliographer. Pardo de Tavera was regarded as a man of extensive knowledge and one of the most varied Filipino writers of his generation (except for Rizal). From medicine to paleography, linguistics, numismatics, maps, history, material romances, education and social concerns. He authored on a variety of disciplines. "The Medicinal Plants of the Philippines," which was published in 33 editions between 1892 and 2016, is one of his most well-known publications. It all started on Cavite Arsenal where the Filipino workers and soldiers were not happy because they were under the iron-fisted rule of Rafael Geronimo Cayetano Izquierdo y Gutiérrez who was a Spanish military officer, politician, and statesman who lived from September 30, 1820 to November 9, 1883. From 4th of April 1871 to 8th of January 1873, he was appointed by King Amadeo of Spain as the Governor-General of the Philippines. In contradiction to his predecessor, he became known for his "Iron Fist" form of governance. From March to April 1862, Izquierdo served as the Governor-General of Puerto Rico. He implemented strict policies which took away the rights of the arsenal workers in Cavite. GovernorGeneral Izquierdo abolished the workers’ privilege of exemption from paying the taxes or annual-tribute which was imposed to show Filipinos’ loyalty to the King of Spain and from rendering the polo y servicio (forced labor) where they could be assigned in any place despite unhealthy and hazardous conditions such as in making of roads and ships. Although there are conditions for this forced labor for the sake of the laborers, it was often violated which resulted in many Filipino workers to die from overworking. Due to the changes dealt by Izquierdo, this triggered the arsenal workers and soldiers to stage an uprising against the Spanish officials in charge of the fort. On the night of January 20, 1872 at the Cavite Arsenal, around 200 Filipino laborers and military personnel led by Sergeant Fernando La Madrid carried out the mutiny. Fernando La Madrid was a mestizo sergeant who prompted the mutiny because Spanish authorities forced his co-soldiers in the Engineering and Artillery Corps to pay personal taxes from which they had subsequently been excused. They were required to pay a monetary payment in addition to doing "polo y servicio," or forced labor, under the terms of the taxes. The signal among these mutineers to start attacking was the firing of rockets from the walls of the city. The Cavite rebels mistook a rocket launch in commemoration of St. Loreto, patron of Sampaloc, for a pre-planned signal for the insurrection coming from the general direction of the city. The Sampaloc festival, typically held in December, had unfortunately been moved to January 20 that year. The mutineers were also expecting reinforcements from Manila but they never came, contributing to their utter defeat. The mutineers had apparently anticipated to be joined by their compatriots from the 7th infantry company, which was tasked to police the Cavite square. They were terrified, however, when they gestured to the 7th infantry troops from the fort's walls and their teammates did not advance to join them. Instead, the firm began to attack them. The insurgents decided to barricade the entrances and await reinforcements from Manila in the morning. This mutiny caught wind quickly allowing the Spanish general to send reinforcements which easily defeated the mutiny. (Niguid, n.d.) The following day, a regiment led by General Felipe Ginoves surrounded the fort until the mutineers submitted, at which point he ordered his men to fire on all those who had surrendered including La Madrid. Within 10 days of the end of the mutiny, the Spanish military held interrogations of captured rebel soldiers and arrested civilians. Izquierdo’s account has details regarding the later interrogation of Bonifacio Octavo, who plays a vital role as a participant observer of the event and was a second Mestizo sergeant of the First Infantry Regiment in Cavite fort, who pledged to the revolt, and repented before the rebellion began. He testified during his interrogation that on the 20th of January 1872, he sailed to Cavite, Viejo then proceeded to sail back and forth, and ending up traveling to Bataan, where he took refuge in the mountains, only to be found and captured in the second week of September, 1872. The Spanish military tried him for 10 days and later confessed that in the month of November or December of 1872, a marine infantry corporal, Pedro Manonson, gave him a document exhorting all local soldiers and estimated forces involved in the insurrection. In October 1871, he met a certain sergeant, Madrid, Vicente Generoso, Francisco Saldua, an unknown artillery corporal, another marine corporate infantry, a previous sergeant, and many more in Manonson's house on Cavite's main street. In the afternoon, Generoso handed the gathering a sheet of paper with a list of estimates of forces primed for a rebellion. According to Octavo, Saldua informed the group that the troops Fathers Burgos, Gomez, Zamora, and Guevara, as well as other leaders, would direct the movement revolt. In Cartagena, Spain, Octavo was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment. He was also condemned to be chained for the entire life. After suffering utter loss, some arsenal workers were captured and asked to speak against the three prominent Filipino priests, Fathers Mariano Gómes de los Ángelesz, José Apolonio Burgos y García, and Jacinto Zamora y del Rosario, later collectively called “Gomburza.” Father José Apolonio Burgos y Garca (February 9, 1837 – February 17, 1872) was born in the Philippines and of Spanish ancestry. He was a parish priest at Manila Cathedral and was close to liberal Governor General de la Torre. He was an outspoken supporter of the clergy's Filipinization. Father Jacinto Zamora y del Rosario (August 14, 1835 to February 17, 1872), was also Spanish, born in the Philippines. He was the parish priest of Marikina and was known to be unfriendly to and would not face any arrogance or authoritative behavior from Spaniards coming from Spain. Father Mariano Gómes de los Ángelesz (August 2, 1799 to February 17, 1972) was a Chinese-Filipino, born in Cavite. He was the most senior of the three of them, serving as Archbishop's Vicar in Cavite. He quietly accepted the death penalty, as if it were his punishment for being pro-Filipinos. These three priests were looking to push for secularization, they were looking for more purpose in the church as opposed to being assistants to Spanish friars. After being pinned as the masterminds of the mutiny the GomBurZa were publicly executed at Bagumbayan by a Garotte, a metal collar used to strangle someone to death. This was to strike fear into anyone who had ideas of going against the Spanish government. Not only them but many of the best known Filipinos were denounced to military authorities, such as, the sons of Spaniards born in the island and men of mixed blood (Spanish and Chinese), as well as the Indians of pure blood or the Philippines Malays, were prosecuted and punished without distinction by the military forces. Joaquin Pardo de Tavera, P. Mendoza, Joaquin Pardo de Tavera, Antonio M. Regidor, Guevarra, Priests Mariano Sevilla, Feliciano Gomez, Ballesteros, Jose Basa, Antonio Lawyers Carillo, Basa, Enriques, Crisanto Reyes, Maximo Paterno, and many more were condemned to life in jail on the Marianas Islands. The Government secured on terrorizing the FIlipinos with its unjust and unnecessary punishment to the people they mention that are part of overthrowing the Spanish Sovereignty in the Philippines despite the fact that there hadn’t any intention to topple the Spanish Government, this lead to the birth of Philippine Nationalist that sparked tremendous feelings of hatred and resentment among Filipinos and question the Spanish Authority and demanded a reform. Dr. Jose Rizal, together with his brother Paciano, witnessed their assassination and decided to write El Filibusterismo, a book in memoriam to the Filipino Martyrs, which triggered the Spanish government and declared him an enemy of the Spaniards. SPANISH VERSION Jose Montero y Vidal wrote it from the perspective of the Spanish. He is a well-known Spanish writer who developed a variety of literary works documenting the different significant events in the Philippines, which is his field of expertise. His interpretation about the Cavite Mutiny, which also includes his first-hand account during the event, is one of his contribution works to the Real Academia de la Historia, a Madrid-based institution that houses a collection of Spanish historical events. By the latter quarter of the 19th century, he had been recognized as one of the greatest specialists, and several of his works are still used as a reference to date. Jose Montero y Vidal saw the Filipinos' Cavite Mutiny as a way to get rid of Spanish settlers as the rulers of the Philippines. However, Vidal had just described the event briefly, he did not really explain the complete details of what truly happened on the night of January 20, 1892. He only emphasized on his account this particular event which is when the attack started after the signal of insurrection was through firing rockets in the sky. On this attack, the Cavite native soldiers along with Sergeant La Madrid have killed the fort commander and hurt his wife leading to their arrests and sentences. Moreover, Gov. Gen. Rafael Izquierdo, the administrator of the country during that time, supports the account of Jose Vidal and says that the revolt was already planned by the local protestant churches, mestizos, and professionals as a rebellion against the Spanish government abuses. (Pugay, 2012) After seeing the reports of this mutiny, Izquierdo saw this as his opportunity to take down the secularization movement that Filipino Priests were fighting for and the targets for this were the GomBurZa fathers who were prolific in their time: Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora. Due to the threat of the Spanish to be suppressed by the native clergy, the judgment was made and they accused the Filipino secular priests of death by public strangulation at Bagumbayan in 1872. Others were also indicted and sentenced to death after the GomBurZa were killed, including significant instigators like Sergeant Lamadrid. Patriots like Joaquin Pardo de Tavera, and Antonio Ma. Regidor, Jose, and Pio Basa, as well as other lawyers and attorneys, have been charged with lifetime imprisonment and have been prohibited from practicing the law by the Audencia. (Koh, n.d) It was considered as one of the most tragic events in Philippine history, and most important lesson for Filipinos to become more nationalistic and committed in their fight for independence and freedom from colonizers. For the Spaniards they thought that the mutiny was a premeditated attack and they also expected one in Manila, they saw this mutiny as an attempt of the Indios/Filipinos to overthrow the Spanish government. After seeing the reports of this mutiny, Izquierdo saw this as his opportunity to take down the secularization movement that Filipino Priests were fighting for and the targets for this was the GomBurZa fathers who were prolific in their time. In addition, Montero y Vidal's account had only focused on the conspiracy of the 1872 Cavite Mutiny, the instigators, rebels, their arrests and sentences. Izquierdo’s Account of the Mutiny is contained within a letter that was sent to the Overseas Minister, written 10 days after the mutiny, after the Spanish government had already held interrogations against the captured mutineers. According to Izquierdo, the mutiny began hours before midnight in Manila, when the skyrockets signaled the mutineers to begin although mistook the fireworks from fiesta of Sampaloc as a signal instead of waiting for the actual signal to be released in Manila by means of cannon shots (contradicting to what he said above regarding the signal being given by skyrockets). The objective was to create fires in Tondo to confuse the authorities so that they could seize Fort Santiago. Cavite's artillery and marines would rise, backed up by 500 men led by the pardoned bandit chief, Casimiro Camerino, who were waiting in Bacoor. By stationing a warship in the tiny stretch of land connecting Bacoor and Cavite, these reinforcements were kept from joining the rebels. The news of the revolt reached Izquierdo via a message delivered by the navy; those who attempted to transmit it by land were slain by Camerino men. He instantly dispatched military soldiers to Cavite. There have been Anonymous Reports delivered to Gen. Gov. Izquierdo about the mutiny's intentions, which revealed that the head of the revolt is the Very Reverend Father Burgos in Manila, and the artillery sergeants and corporals in Cavite. As a result, all three regiments remained loyal to Spain in both Manila and Cavite, and the mutiny was doomed. SUMMARY OF BOTH SIDES Regardless of the many accounts of the tale, the 1872 Cavite Mutiny occurred not because the arsenal employees sought to overthrow the Spanish government and fight for their independence, but rather because the laborers were dissatisfied with how they were treated and their rights were removed from them. The Spaniards, on the other hand, saw it differently and attempted to extinguish all dreams and ambitions for freedom. They also seized this chance to carry out the secularization drive of Filipino priests by making the GomBurZa martyrs. Another important spectacle was how the young Jose Rizal observed the martyrdom, which woke him up and clearly influenced him to write his renowned novels, which were instrumental in propelling the Philippine Revolution. PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED While unraveling this narrative, there are some problems that the researchers have encountered. First, is that the 1872 Cavite Mutiny is a vital historical incident that is not as widespread as compared to other stories within the Philippines. The researchers believe that only those remarkable events after the mutiny were being recognized by the people such as the 1896 Philippine Revolution and 1898 Independence Declaration, despite how important the Mutiny's role is in leading to these monumental events. And it seems true, who would recognize a small mutiny that has approximately two hundred mutineers and was declared failed by the Spaniards in just two days, without knowing that this mutiny will cause the Filipinos’ nationalism to rise. In addition, given that there are two faces of the story, namely the Filipino and Spanish version adds up to the confusion of people regarding what truly the mutineers aim to accomplish. With this, the researchers believe that the Cavite Mutiny event left an unclear impression for many, and its importance is not recognized as compared to others. Another point of contention to consider is the two different sides of the story consisting of the Filipino’s side and the Spanish’s side where one side was a simple mutiny due to the dissatisfaction of workers and the other that saw this mutiny as a attempt to gain freedom which they also used to their advantage to try to get rid of the calls for secularization. RECOMMENDATIONS/SOLUTIONS Having considered the different problems that arise from studying the 1872 Cavite Mutiny, the researchers have come up with a few solutions that can eliminate the difficulties that are currently present within the current narratives of the story. First and foremost is the problem with the obscurity surrounding the 1872 Cavite Mutiny. There are only a handful of videos and sites that cover this event, therefore limiting the resources about the topic which made the history of Cavite Mutiny not widespread to common knowledge. According to Pugay (2012), not everyone was aware that there are various accounts in reference to the same event. Because this incident resulted in another tragic but crucial portion of our history, the execution of GOMBURZA, which was a critical component in the awakening of nationalism among Filipinos, all Filipinos should be informed of both sides of the story. Due to the presented evidence, the researchers propose a solution in which this historical event should be disseminated across a large audience, especially the youth. This significant piece of history could be a vital piece of their growth. In order to reach the young audience, adjusting the basic curriculum. This event could also be informative through other media such as television segments or social media. Research articles can also be a way for the people to know about this historical occurrence. Every Filipino citizen whether youth and workers should be informed about it. Next is the problem with the cluttered manner and speculations made in the story due to the two versions of the 1872 Cavite Mutiny, written by two different people. It is the Filipino version written by Dr. Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo De Tavera and the Spanish Version by José Montero y Vidal. There are bound to be biases, misinterpretation and finding the middle ground between the two is a must. According to Samson (2020), the 1872 Cavite Mutiny is one of the most significant issues and occurrences in Philippine history. Even in today's period, in the digital age, teachers should discuss or teach history. Furthermore, the internet has the ability to deceive us into searching for different types of information, if we allow it to and do not fail to distinguish or weight data from various sources. As for this, the evidence of information that is visible on the internet is what we cannot rely on. This is why the researcher suggest to have a comprehensive and cohesive telling of these accounts without focusing on the different point of views, instead focusing on the main timeline and the significance of this tale since it was supposedly the starting point or the beginning the ultimately led to the Philippine Revolution that gave the Filipino their freedom after centuries under Spanish rule. Focus on dealing with facts in order to understand truthfully the relevant information in the history of Cavite Mutiny. Samson (2020) added that it is important to signify critical thinking. Critical thinking is one of the most important skills we should have in the twenty-first century. It is crucial to develop critical thinking skills on this day since our possibilities of being gullible or credulous are decreasing. In this age of knowledge and uncertainty, the twentieth century demonstrates importance. In conclusion, we should learn more and gather factual evidence about what happened during the Cavite Mutiny. References: Etimología de los nombres de razas de Filipinas. (2021). Worldcat.org. https://www.worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n85217017/ Hisona, H. (2010). The Forced Labor and Tribute of the Filipinos During Spanish Period.EzineArticles. https://ezinearticles.com/?The-Forced-Labor-and-Tribute-ofthe-Filipinos-During-Spanish-Period&id=5620267 Medina, M. (2017). DID YOU KNOW: Lt. Gen. Rafael de Izquierdo. INQUIRER.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/863161/did-you-know-lt-gen-rafael-de-izquierdo Polo y Servicio. (2019). TAGALOG LANG. https://www.tagaloglang.com/polo-yservicio/ Pugay, C. A. P. (2012). The Two Faces of Cavite Mutiny. Retrieved from https://nhcp.gov.ph/the-two-faces-of-the-1872-cavite-mutiny/ Samson, E. (2020). Cavite Mutiny. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346989320_Cavite_mutiny The 1872 cavite mutiny. Filipino Journal. (2016, January 20). Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://filipinojournal.com/the-1872-cavite-mutiny/ Remembering the Gomburza: In anticipation of the 150th anniversary of their martyrdom in 2022. National Historical Commission of the Philippines. (2021, February 16). Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://nhcp.gov.ph/remembering-the-gomburza-in-anticipation-of-the150th-anniversary-of-their-martyrdom-in-2022/ The execution of Gomburza. read.cash. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://read.cash/@rapsantos/the-execution-of-gomburza-2a99ad12 Niguid, N. (n.d.). The Cavite Mutiny. Retrieved from http://www.stuartxchange.com/CaviteMutiny.html Koh, E. (n.d.). The 1872 Cavite Mutiny. Filipino Journal, 26(4). Retrieved from The 1872 Cavite Mutiny - Filipino Journal SCHUMACHER, J. N. (2011). The Cavite Mutiny Toward a Definitive History. Philippine Studies, 59(1), 55–81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42635001