Economic Principles: Decision Making, Markets, and Elasticity

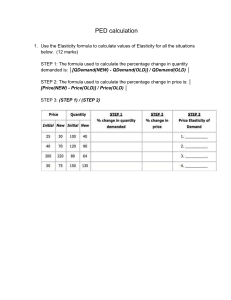

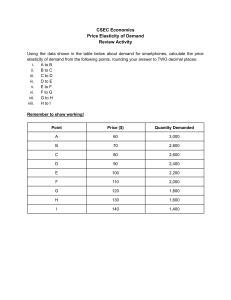

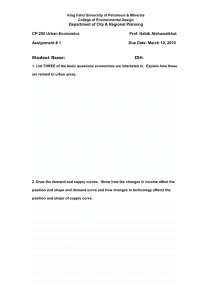

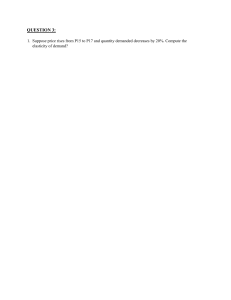

advertisement

The fundamental lessons about individual decision making are that people face trade-offs among alternative goals, that the cost of any action is measured in terms of forgone opportunities, that rational people make decisions by comparing marginal costs and marginal benefits, and that people change their behavior in response to the incentives they face. The fundamental lessons about interactions among people are that trade and interdependence can be mutually beneficial, that markets are usually a good way of coordinating economic activity among people, and that the government can potentially improve market outcomes by remedying a market failure or by promoting greater economic equality. The fundamental lessons about the economy as a whole are that productivity is the ultimate source of living standards, that growth in the quantity of money is the ultimate source of inflation, and that society faces a short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment. There are two ways to compare the ability of two people to produce a good. The person who can produce the good with the smaller quantity of inputs is said to have an absolute advantage in producing the good. The person who has the smaller opportunity cost of producing the good is said to have a comparative advantage. The gains from trade are based on comparative advantage, not absolute advantage. Decisions are made by households and firms. Households and firms interact in the markets for goods and services where households are buyers and firms are sellers and in the markets for the factors of production where firms are buyers and households are sellers. The demand curve shows how the quantity of a good demanded depends on the price. According to the law of demand, as the price of a good falls, the quantity demanded rises. Therefore, the demand curve slopes downward. In addition to price, other determinants of how much consumers want to buy include income, the prices of substitutes and complements, tastes and preference, future expectations, and the number of buyers. If one of these factors changes, the demand curve shifts. The supply curve shows how the quantity of a good supplied depends on the price. According to the law of supply, as the price of a good rises, the quantity supplied rises. Therefore, the supply curve slopes upward. In addition to price, other determinants of how much producers want to sell include input prices, technology, expectations, and the number of sellers. If one of these factors changes, the supply curve shifts. The intersection of the supply and demand curves determines the market equilibrium. At the equilibrium price, the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. The behavior of buyers and sellers naturally drives markets toward their equilibrium. When the market price is above the equilibrium price, there is a surplus of the good, which causes the market price to fall. When the market price is below the equilibrium price, there is a shortage, which causes the market price to rise. Elasticity is a measure of how much buyers and sellers respond to changes in market conditions. The price elasticity of demand measures how much the quantity demanded responds to changes in the price. Demand tends to be more elastic if close substitutes are available, if the good is a luxury rather than a necessity, if the market is narrowly defined, or if buyers have substantial time to react to a price change. The price elasticity of supply measures how much the quantity supplied responds to changes in the price. This elasticity often depends on the time horizon under consideration. In most markets, supply is more elastic in the long run than in the short run. The income elasticity of demand measures how much the quantity demanded responds to changes in consumers’ income. The cross-price elasticity of demand measures how much the quantity demanded of one good responds to changes in the price of another good. Inelastic demand means a change in the price of a good, will not have a significant effect on the quantity demanded. The Determinants of Price Elasticity: The price elasticity of demand depends on: the extent to which close substitutes are available. whether the good is a necessity or a luxury how broadly or narrowly the good is defined. the time horizon: elasticity is higher in the long run than the short run. The Determinants of Supply Elasticity • The more easily sellers can change the quantity they produce, the greater the price elasticity of supply. • For many goods, price elasticity of supply is greater in the long run than in the short run, because firms can build new factories, or new firms may be able to enter the market. Rule of thumb: The flatter the curve, the bigger the elasticity. The steeper the curve, the smaller the elasticity.