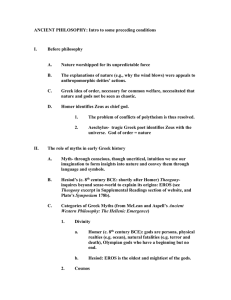

Anatomy of Myth: Interpretation from Presocratics to Church Fathers

advertisement