Mirrors as Portals Images of Mirrors on Ancient Maya Ceramics

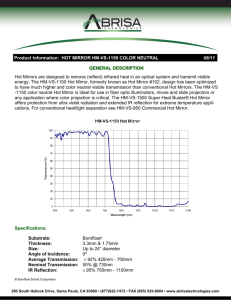

advertisement