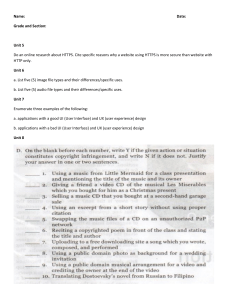

Psychology of Popular Media Interactive Decision-Making in Entertainment Movies: A Mixed-Methods Approach Diana Rieger, Tim Wulf, Claudia Riesmeyer, and Larissa Ruf Online First Publication, May 5, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000402 CITATION Rieger, D., Wulf, T., Riesmeyer, C., & Ruf, L. (2022, May 5). Interactive Decision-Making in Entertainment Movies: A MixedMethods Approach. Psychology of Popular Media. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000402 Psychology of Popular Media © 2022 American Psychological Association ISSN: 2689-6567 https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000402 Interactive Decision-Making in Entertainment Movies: A Mixed-Methods Approach Diana Rieger, Tim Wulf, Claudia Riesmeyer, and Larissa Ruf This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Department of Media and Communication, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich Entertainment researchers often differentiate whether media elicit hedonic or eudaimonic entertainment experiences when investigating mental processes during movie reception. Recent audiovisual entertainment formats provide recipients with an interactive role, for example, deciding between actions and options. This study investigates the impact of interactive decision-making in movies on entertainment experiences. By using a mixed-methods approach, we complemented a laboratory experiment (IV: interactivity of movie stimulus, N = 60) with subsequent reflective interviews to get deeper insights into cognitive and emotional processes when consuming entertainment. The results demonstrated that entertainment experiences were higher in the interactive than in the noninteractive movie condition. Furthermore, this intensified entertainment experience is explained through decision-making processes and mental engagement with the protagonist. We discuss these findings in light of the role of engagement with fictional characters and their implications for entertainment theory and recent entertainment formats. Public Policy Relevance Statement This article seeks to explain how we cognitively apprehend and emotionally process movies that integrate our decisions as viewers, so-called interactive movies. Using the movie Bandersnatch as an example, we show that the audiovisual decision-making process and the main character’s engagement can explain our entertainment experiences in interactive movies. Keywords: interactive entertainment, reflection, engagement, mixed-methods approach, Bandersnatch Just watched #Bandersnatch. Or did I play it? Was it a game? Anyway, my life won’t be the same ever again! (Ratan, 2019) Although such interactive narratives have become more and more popular, there is a lack of empirical evidence on how interactivity in movies shapes cognitive and emotional processes. Furthermore, there is little research on entertainment experiences compared with watching “traditional,” noninteractive movies, especially considering eudaimonic, “meaningful” narratives (see Elson et al., 2014, for meaningful player experiences in digital games). Interactive elements provide opportunities that are unable to be matched when only considering a passive role for recipients. For instance, digital games offer players opportunities to make their own decisions, explore the story world through their own perspectives, and form a unique way of experiencing the game story through interactivity (Elson et al., 2014). Such interactive elements equip the player with autonomy and competence (Oliver et al., 2016; Rieger et al., 2014; Tamborini et al., 2010) and a different connection toward the avatar in the story (Bowman et al., 2016). So, it does not seem surprising that Bandersnatch was considered some kind of game for many viewers (Ratan, 2019, see aforementioned quote), as entertainment can be a motivation to engage with interactive elements (Chung & Yoo, 2008). Furthermore, interactive features—in digital games but also other narratives— pose challenges to users (Bartsch & Hartmann, 2017) that come along with different processing of the narrative, for instance, higher levels of transportation (Green & Jenkins, 2014), more This quote reflects how viewers reacted to Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, the interactive film that Netflix released at the end of 2018 that allowed the viewers to actively participate in deciding how the plot should continue for the main character. The unusual format has thus attracted worldwide attention, as it “has never been done before in the series and film business—at least not on such a large scale” (Neon, 2019). However, Bandersnatch is not an isolated case on Netflix. Other interactive formats are already available on the streaming platform in addition to the spin-off of the Black Mirror series (e.g., the well-known film Puss in Boots for children; Netflix, 2017). Diana Rieger https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2417-0480 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2671-5106 Tim Wulf https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9105-1628 Claudia Riesmeyer Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Diana Rieger, Department of Media and Communication, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Oettingenstr. 67, Munich 80538, Germany. Email: diana.rieger@ifkw.lmu.de 1 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 2 RIEGER, WULF, RIESMEYER, AND RUF positive affect (Parrott et al., 2017), or high levels of curiosity and suspense (Roth & Koenitz, 2019). Vorderer et al. (2001) found that people differ in processing interactive movies depending on their cognitive capacities. Similarly, the appreciation of playing interactive games varied as a function of perspective-taking (Bowman et al., 2016). Studying Bandersnatch, Roth and Koenitz (2019) further found perceived meaningfulness as one of the central predictors for enjoyment. Although Elson et al. (2014) concluded that “the interactivity adds a whole new layer of user experiences affecting both hedonic and eudaimonic gratifications” (p. 524), little research has examined emotional and cognitive processes that differ between interactive and noninteractive viewing modes. To investigate the entertainment experience of interactive, meaningful narratives and mental processes associated with interactivity, we conducted a mixed-methods approach combining an experimental manipulation of interactivity in a movie set and subsequent qualitative reflective interviews (a) to better understand processes happening during reception of entertainment, (b) to compare these processes between an interactive versus a noninteractive version of a movie, and (c) to test how these processes relate to entertainment experiences. Theoretical Background Two-Process Models of Entertainment To get a better understanding of entertainment experiences, researchers often distinguish between hedonic and nonhedonic entertainment experiences. Usually, hedonic experiences arise when a story is funny, puts the user in a good mood, has a happy ending, or features morally good protagonists. Researchers defined enjoyment as the core of entertainment (Vorderer et al., 2004), an experience characterized by relaxation, diversion, fun, and joy (Bosshart & Macconi, 1998). In contrast, there exist several definitions of nonhedonic entertainment experiences: First, they can be elicited when the story speaks to (or satisfies) intrinsic human needs, in particular the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as described in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Self-determination theory assumes that humans can achieve the satisfaction of these needs through media consumption. This was empirically supported for movies (Adachi et al., 2018; Wirth et al., 2012), computer games (Rieger et al., 2014; Tamborini et al., 2010, 2011), Facebook (Reinecke et al., 2014), or digital media, in general (PfaffRüdiger & Riesmeyer, 2016; Schneider et al., 2018). A second approach on nonhedonic entertainment experiences focuses on stories that provide deeper meaning, demonstrate acts of moral beauty, challenge the protagonist, and depict important life values. This nonhedonic entertainment experience is often called eudaimonic (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010; Oliver & Raney, 2011)1. It results in experiences of meaningful portrayals and affective reactions, also defined as appreciation, “the perception of deeper meaning, the feeling of being moved, and the motivation to elaborate on thoughts and feelings inspired by the experience” (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010, p. 76; Vorderer, 2011). Wirth et al. (2012) integrated these two approaches on nonhedonic entertainment (the satisfaction of intrinsic needs and the experience of meaning in life) and provided two general foci of eudaimonic entertainment experiences. On the one hand, individuals evaluate the viewing process via thoughts and feelings that rely on the storyline and characters in the media content. On the other hand, individuals make comparisons and assess their own lives. Media content can trigger such evaluations, but they ultimately relate to viewers’ self and life (Oliver & Raney, 2011). Methodologically, Wirth et al. (2012) provided evidence for these two foci by demonstrating two second-order factors in their Eudaimonic Entertainment Scale: First, relatedness, activation of central life values, and personal growth together display a deeper reflection of the media content, “an intense reaction to emotions elicited by, and values conveyed through, the plot of a movie and the characters depicted” (Wirth et al., 2012, p. 419). Second, purpose in life and autonomy represents life evaluation that led participants “to think about their own lives by comparing the fortunes of the characters in the movie with their own fates” (Wirth et al., 2012, p. 419). This process brings about a certain feeling of autonomy and contentment with one’s life. Neither deeper reflection nor life evaluation differed between a movie with a happy ending and one with a sad ending. That is, both processes are not particularly predominant to mere positive or negative story content per se. Although mainly used in movies, both factors could be applied to digital games or interactive features in narratives in general. We, therefore, question whether interactivity is associated with deeper reflection and life evaluation (Research Question 1). Interactivity and Entertainment Interactivity might shape entertainment experiences. There are many ways to define interactivity, emphasizing interaction and seeing two-way or multiway communication as a prerequisite (Kiousis, 2002). According to Roth and Koenitz (2019), interactive digital narratives are “an emerging expressive form of narrative in the digital medium, implemented as computational system which allows users to participate in the experience, and influence the unfolding of one narrative out of a space many potential narratives” (p. 249). Green and Jenkins (2014, p. 481) coined the term “interactive narrative” as “a story in which the reader has opportunities to decide the direction of the narrative, often at a key plot point.” Nowadays, video games are probably the best-known form of interactive entertainment media. Comparing a simple game (e. g., Pacman) with a gameplay video of the same game led to more distraction from a negative mood and more mood repair (Rieger et al., 2014). In a similar setup, the game condition yielded an increased sense of embodied presence than the gameplay condition (van’t Riet et al., 2018). Interactivity also correlated with increased involvement with the media content and increased enjoyment (Reinecke et al., 2011). Despite these advantages of interactive entertainment, keep in mind that noninteractivity also comes with certain benefits. Humans are motivated and able to have a vivid imagination of stories (Slater et al., 2014): They do not only react to them as if they were real (Busselle & Bilandzic, 2008) but also conclude them for their own life (Murphy et al., 2011). In addition, many studies see 1 Eudaimonic entertainment experiences are often also termed inspirational, meaningful, or self-transcendent. In the current article, we will rely on the term eudaimonic. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. INTERACTIVE DECISION-MAKING IN ENTERTAINMENT MOVIES passive entertainment consumption as beneficial to experience relaxation and unwinding from daily hassles (Reinecke et al., 2011; Rieger et al., 2014, 2017). Studies that compared interactive with noninteractive content are often based on very simple games such as Tetris or Pacman and might be boring to watch, thus not resembling the experience for narrative video games. However, with the evolution and development of video games, the aspirations to create deep narrative worlds became higher (Christy & Fox, 2016), as well as to invest more in ways to use the advantages of interactivity in storytelling. Christy and Fox (2016) highlighted that identification with story characters is a crucial mechanism that generates other user experiences out of narrative content. Cohen (2001) defined identification as the adoption of the perspective of a character and consequently experiencing empathic emotions. Identification is often mentioned together with transportation, defined as focusing on attention, emotion, and imagery in a story (Green & Brock, 2000). Both definitions share an inevitable overlap and are difficult to disentangle. However, Moyer-Gusé (2008) argued that identification goes beyond the involvement with the narrative story world itself. Transportation and identification can increase the enjoyment of a narrative and its appreciation (Slater et al., 2014). Because of their involving nature, interactive narratives may foster identification processes better than noninteractive, traditional narratives. They allow readers or viewers to adopt character goals actively (Green & Jenkins, 2014). Moreover, Green et al. (2004) argued that interactivity should also facilitate transportation, leading to an immersive and enjoyable narrative experience. Hand and Varan (2008) demonstrated that interactive TV programs were more immersive and entertaining than traditional programs. Furthermore, the experienced meaningfulness in interactive narratives was the main predictor for enjoyment (Roth & Koenitz, 2019). Based on these results, we hypothesized that an interactive narrative would result in (a) higher transportation, (b) higher identification, (c) higher enjoyment, and (d) higher appreciation compared with a noninteractive version (Hypothesis 1). Green and Jenkins (2014) found no differences in perceived difficulty between interactive and noninteractive stories. In contrast, the results of an early study on audiovisual narratives by Vorderer et al. (2001) point toward the assumption that people differ in processing interactive movies depending on their cognitive capacities. Whereas those participants with low cognitive capacity enjoyed less interactive versions more, those with higher cognitive capacity enjoyed higher levels of interactivity. This study’s results show that interactive movies can pose more challenges to viewers than noninteractive movies. Hartmann (2013) described the potential role of cognitive and affective challenges in individuals’ entertainment experiences. According to his framework, affective challenges mainly result from the experience of intense negative affect, for example, when the protagonist struggles with stressful situations. Cognitive challenges can arise from media content if it is difficult to process due to (a) high complexity, (b) in opposition to one’s intuitive dispositions, (c) structural or content features, or (d) dissonant information (Bartsch & Hartmann, 2017). All these factors together point toward the idea that interactive narratives can pose more challenges (in terms of structural or content features) to individuals. Relatedly, a simple video game led to higher subjectively reported task load and arousal levels than a noninteractive gameplay video of the same content (Rieger et al., 2015). In their experiment on challenging versus less challenging 3 movies, Bartsch and Hartmann (2017) demonstrated that lower affective and cognitive challenges resulted in more fun (enjoyment). In turn, both affective and cognitive challenges led to higher levels of appreciation. Based on the notion of cognitive and affective challenges during entertainment consumption, this study aims to investigate mental processes in the reception process. Most entertainment research only has a limited understanding of processes happening during the reception of interactive or noninteractive entertainment media because most quantitative research solely relies on post hoc measurement via questionnaires. That is, the depth of mental processes is often not assessed. Hence, we question how interactivity is related to cognitive processes in the reception process (Research Question 2). Method We applied a between-subjects design to address the assumptions (Hypothesis 1) and research questions (IV: interactive vs. noninteractive version of a narrative). We complemented a laboratory experiment with reflective interviews (Mann, 2016; Roulston, 2010). With this design, we apply a convergent parallel mixed method to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research questions (Creswell, 2014). Through this design, we were able to combine quantitative questionnaire results with qualitative analyses to get a deeper insight into the subjective experience in the reception process and integrate findings to reach an overall interpretation. We provide (a) full measures used in the quantitative part of the study (see Appendix A), (b) all interview transcripts of the qualitative interviews (see Appendix B), and (c) full data and syntax of quantitative analyses online via the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/zd5h7/?view_only=996ea5a432aa4b75b510b 48cadc2483a). Participants and Procedure A total of N = 62 participants took part in a laboratory experiment at Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich. Two trials were excluded due to technical issues, leading to a final sample of N = 60 participants (age: M = 22.25, SD = 2.55; 50% female). The sample consisted of mainly student participants (86%). Only participants who did not know Bandersnatch and the idea behind it (=interactivity) took part in the study. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants were welcomed and introduced to the process of the study. Participants signed informed consent and were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions. They were asked to watch an excerpt from Bandersnatch for 30 to 40 min until they reached a specific scene2. In the noninteractive condition, we taped the lower part of the TV with black tape. Participants thus could not see that the movie was originally interactive. In this condition, decisions were made randomly by the movie. The viewing time depended on the duration of decision-making during the reception. Afterward, participants were 2 There are different options how the movie can end. Two scenes were defined beforehand on when to stop the screening. These scenes were chosen because each interactive version runs through one of the scenes after 30 to 40 min of watching allowing for most consistent content between conditions and decisions. 4 RIEGER, WULF, RIESMEYER, AND RUF guided through a reflective interview with the experimenter and asked to fill out a quantitative questionnaire. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. The Plot of the Movie Bandersnatch Black Mirror: Bandersnatch is considered an interactive film, released on December 28, 2018, on the streaming platform Netflix. The film was released by the makers of the British series Black Mirror. Each episode takes viewers into a dystopian world in which the effects of technology and media on society are addressed. Bandersnatch has taken up this idea. The film takes place in London in 1984 and deals with the young programmer Stefan Butler, whose greatest wish is to create an interactive computer game based on the science fiction novel by Jerome F. Davies. The game’s goal is to walk through a labyrinth of corridors and avoid the creature called “Pax.” At individual junctions, decisions shown on the screen by an instruction must be made by the viewer. In the movie, the viewer gets to know different characters that have a meaning in Stefan’s life. They will learn about the complex relationship with his father, the death of his mother, his admiration for the famous game developer Colin, and the therapy sessions with the psychologist Dr. R. Haynes. There are numerous ways in which the movie can end, depending on the viewer’s paths during the decision-making process. For instance, the film begins with initially straightforward decisions about Stefan’s breakfast and ends with moral decisions about life or death. It should be emphasized that this is a very self-referential film. The content— the making of decisions—is also reflected in the type of prescription. Thus, viewers see what they are actively doing. In preparation for the study, we discussed how to achieve internal validity at most. To make the interactive and noninteractive conditions most comparable, we decided to start the movie with every participant at the very beginning. First, this allows the interactive group to familiarize themselves with how decisions are made in simple situations (breakfast). Second, the first decisions had no significant impact on the whole narration. Therefore, the content shown was reasonably similar between conditions (the number of ends could not be achieved). To this point, the interactive version was still relatively in line with the noninteractive version, as the personal decisions impact the experience more over time. Reflective Interviews This method aims at stimulating participants to reflect and articulate thoughts and feelings through a stimulus (Mann, 2016): “Rather than only reporting their experiences descriptively, interviewees, with the support of interviewers, have the opportunity to share the meanings of the reality surrounding them and the events of their own lives, without being interpreted arbitrarily only by the interviewer” (Pessoa et al., 2019, p. 2). One advantage of the method is that a reception process can be traced—for example, when, why, and what decision was made (Crutcher, 1994). In the present study, reflective interviews were used to articulate and justify perceptions of the reception situation and decisions made. In addition, participants in both groups had the opportunity to express their thoughts and feelings. The interviews took place after the reception of the film. The participants were asked to answer three (noninteractive condition) or four open questions (interactive condition). These questions encouraged the subjects to freely and spontaneously articulate their thoughts during the reception. The questions concerned the constructs as mentioned earlier. We asked for cognitive (“What did you think during the film?”) and emotional processes (“What did you feel during the film?”), identification with the main character Stefan (“How do you feel about Stefan?”), and the reflection of decisions (“What did you make your decisions depend on?”). Participation in the interviews was only possible after provided written consent of the participants. The length of the interviews varied between 3 and 7 min, depending on the reflective capacity of participants (Mann, 2016; Roulston, 2010). All interviews were conducted in person, recorded, transcribed verbatim, anonymized3, and then analyzed using a theory-driven approach (Creswell, 2014). Full interview transcripts are available in Appendix B in our online supplemental materials on OSF (https://osf.io/zd5h7/ ?view_only=996ea5a432aa4b75b510b48cadc2483a). To systematically reduce the data’s complexity, we developed a category system derived from theoretical considerations (Gläser & Laudel, 2013). The category system comprised the following categories: identification with and reflection about the main character Stefan and the movie itself, the mention and evaluation of other characters, and the articulated emotions and thoughts during the reception. Based on these main categories, a line-by-line coding of each transcript was conducted to identify similarities and differences between and within groups. Thus, the main categories were changed or supplemented according to empirical information in the transcripts, applying a combined theory-driven and data-driven analysis strategy (Gläser & Laudel, 2013). Two authors of this study read all transcripts several times; marked, abstracted, and coded relevant passages; and discussed them actively to achieve agreement. Measures All measures were collected on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 7 = totally agree).4 For a complete overview of items (German original items and English translations), see Table S1 in Appendix A in the online supplemental materials in our OSF repository (https://osf.io/zd5h7/?view_only=996ea5a432aa4b75b 510b48cadc2483a). Also, complete data and syntax used in all analyses can be found in this repository. Identification and Transportation We measured Identification with 10 items of Cohen’s (2001) Identification Scale (M = 4.04, SD = 1.41, a = .94). Transportation was assessed using the Transportation Short Scale (Appel et al., 2015). This scale consists of six items (e.g., “I could picture myself in the scene of the events described in the narrative,” M = 4.51, SD= 1.35, a = .89). 3 When the interviews are quoted verbatim in the following, this is done as follows: participant serial number (sex, age, experimental or control group), for example, p1 (f, 22, eg). 4 In addition to the measures reported here, we assessed parasocial interaction with the Para-Social Interactions–Process Scale (Schramm & Hartmann, 2008). This scale consists of 12 items (a= .79, M = 4.31, SD = 0.93). For the sake of scarcity and our line of argumentation, we did not include it in our article. Results are available upon request. INTERACTIVE DECISION-MAKING IN ENTERTAINMENT MOVIES This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Deeper Reflection and Life Evaluation In addition, we measured the underlying processes of eudaimonic entertainment using the Wirth et al. (2012) scale. This scale entails two second-order factors: The factor Life Evaluation (M = 3.33, SD = 1.16, a = .86) is formed by the three subfactors (three items each) Purpose in Life (e.g., “I have a good feeling because the film has shown me how content I can be with my own life”), Autonomy (e.g., “I feel good because now that I have seen this film I feel that I am in charge of my own life”), and Competence/ Personal Growth (e.g., “It felt good to expose myself to the theme of the film”). The second factor, Deeper Reflection (M = 2.86, SD = 1.25, a = .88), consists of two subfactors: Activation of Central Values (e.g., “Altogether, I feel good because Stefan acted responsibly”) and Relatedness (e.g., “It felt good to be captivated by the events around Stefan during the film”). Enjoyment, Suspense, and Appreciation We measured Enjoyment, Suspense, and Appreciation with the scales from Oliver and Bartsch (2010). Enjoyment was represented by three items asking for fun while watching the film (M = 4.93, SD = 1.57, a = .94). Likewise, Suspense was measured with three items asking for a suspenseful experience (M = 4.68, SD = 1.33, a = .82). We calculated Appreciation as a mean score of the Lasting Impression and Thought Provocation subscales (Hofer, 2013; M = 3.80, SD = 1.62, a = .94). Results Testing the Hypotheses We performed a multivariate analysis of variance with condition as the independent variable and Identification, Transportation, Life Evaluation, Deeper Reflection, Enjoyment, and Appreciation as the dependent variables to test our assumptions regarding the effects of condition on all outcome variables. We found a significant multivariate effect of condition, F(5, 52) = 21.13, p , .001, Pillai’s V = .74, hp2 = .74. Mean comparisons for all outcomes across all conditions are reported in Table 1. Based on these results, Hypothesis 1 (a, b, c, and d) can be supported. The interactivity intensified the entertainment experiences. For Research Question 1, it can be held that an interactive narrative leads to more reflection and life evaluation than a 5 noninteractive pendant. Furthermore, and concerning Research Question 2, zero-order Pearson correlations among all dependent variables are depicted in Table 2 and discussed in the Discussion section in light of the qualitative results. Sensitivity analyses regarding the hypotheses using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) revealed that our tests of multivariate global effects had 80% power to detect effects with a size of f2 $ .255 for the given sample size, two groups, and six response variables. According to G*Power, this effect size is equivalent to a Pillai’s V value of .20, which lies below our estimated value for Pillai’s V. Reflective Interviews: Interactivity, Deeper Reflection, and Life Evaluation Results of reflective interviews show that interactivity is strongly linked to identifying with the main character Stefan and, therefore, the possibility of actively influencing the course of action. This connection becomes clear concerning feelings toward the characters (who is positive, who is negatively evaluated?) as well as the direction of attention during the reception (what is noticeable, what is not?) and the nature of feelings during reception and projection onto relevant others (who else is mentioned?). An essential advantage of the reflective interviews is the perception of these connections and the free association of viewers’ thoughts. Identifying the leading actor Stefan and the possibility of interactively determining the course of the action was essentially related to his evaluation. Participants in the interactive condition were more open-minded toward Stefan and felt empathy for him and his life. They wanted to influence Stefan’s actions and woke him up precisely because they decided for him and assumed that their decisions would work better for Stefan. “He was a goodhearted person who needed to be helped,” said p56 (f, 23, eg). This identification led in part to finding oneself in Stefan in the interactive condition (“I see much of him in me. I really wanted him to achieve what he felt was right, and I simply took that over from the way he thought,” p58, f, 23, eg), losing the feeling for reality, and immersing entirely in the setting of the movie: “I almost had the feeling that I was to blame for (Stefan’s) death, the feeling was creepy, and made me forget for a short time that I was just watching a movie and that not everything was reality” (p55, f, 24, eg). This result is also clear from the statement of p15 (m, 29, eg), who asks himself, “I am involved, am I?” Table 1 Effects of Condition on All Dependent Variables Condition Variables Interactive M Noninteractive M Identification Transportation Life evaluation Deeper reflection Suspense Enjoyment Appreciation 5.16 5.54 3.82 3.73 5.61 5.83 4.97 2.93 3.47 2.84 1.99 3.76 4.03 2.63 *** p # .001. F test Effect size SE F (df) h2p .16 .16 .19 .16 .18 .24 .20 102.03*** (1, 58) 86.99*** (1, 58) 12.65*** (1, 58) 56.08*** (1, 58) 6.16*** (1, 58) 29.15*** (1, 58) 65.92*** (1, 58) 0.64 0.60 0.18 0.49 0.49 0.34 0.53 6 RIEGER, WULF, RIESMEYER, AND RUF Table 2 Zero-Order Pearson Correlations Among All Variables Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Condition 2. Identification 3. Transportation 4. Life evaluation 5. Deeper reflection 6. Suspense 7. Fun 8. Appreciation — .80*** — .78*** .86*** — .42* .60*** .60*** — .70*** .85*** .77*** .69*** — .70*** .69*** .76*** .58*** .67*** — .58*** .55*** .68*** .50*** .57*** .62*** — .723*** .71*** .75*** .52*** .67*** .73*** .50*** — This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. * p , .05. *** p , .001. The noninteractive condition was much more reserved in their statements. Participants sometimes did not pay attention to Stefan, reacted indifferently toward him, or judged him negatively. Stefan was described as “sick” (p6, f, 22, cg) and “creepy” (p9, m, 18, cg). Participants seemed to lack personal reference, making it difficult to identify with the protagonist. “I don’t really see myself in Stefan,” p59 (m, 19, cg) pointed out. “Stefan and I are two completely different people, and therefore I cannot really identify with him and his actions” (p8, m, 23, cg). A similar pattern can also be seen in the evaluation of the movie: Whereas the experimental group let themselves be captivated by the plot (“That touched me so much, I never thought it would happen,” p18, w, 24, eg), immersed themselves in the plot, and lost track of time (“To be honest, I’m surprised at first that it really was 40 minutes. That seemed to me much shorter. Madness,” p31, m, 23, eg), participants in the noninteractive condition rather talked about the stylistic means of the film. For example, they praised the camera work, the design (“Hollywood-like,” p38, f, 21, cg), or the staging. The interactivity determined how the film was evaluated and which aspects the interview partners articulated through the think-aloud procedure. The fact that interactivity determined what was perceived and articulated also becomes clear when referring to other actors. In the noninteractive condition, viewers talked about the audience and thus themselves, whom the film encourages to think along with it, about Colin, who was seen as Stefan’s role model, and about Stefan’s parents. They related the portrayal of Stefan to themselves, but without losing distance (like participants in the interactive condition), and differentiated themselves from him and his actions. The interactive condition differed here: Stefan was close to them. The father was judged as an unfair character, unlike the control group, who does not understand Stefan and behaves incorrectly toward him. Colin, Stefan’s antagonist, seemed “suspicious” (p35, f, 20, eg) and “unsympathetic” (p39, m, 22, eg). Participants in the interactive condition established a connection to themselves as viewers. Among other things, they felt guilty of the death of a character—a finding that in turn speaks for the influence of involvement in the evaluation of the movie and its plot. Finally, feelings and thoughts during reception were analyzed to understand the influence of interactivity. As before, interactivity led to differences: The noninteractive condition felt itself to be helpless and somewhat at the mercy of the plot of the movie (“The subject matter was too intense for me, something like that must first have an effect on me and then I usually think about it afterward,” p49, m, 23, cg). Even if participants wanted to help Stefan, they could not influence the plot. This helplessness determined the thoughts during the reception. P25 (f, 19, cg) said, “I always had an oppressive feeling because the film didn’t even show anything positive. Constantly it was all about stress, depression, burn-out, and so on. Didn’t really enjoy watching.” The interactive condition also articulated feelings primarily toward Stefan (e.g., pity, compassion, or sympathy) and toward the movie itself, its making, and the interactivity. “The click itself was very emotional. I enjoyed it and was really interested in it. I found it quite good” (p45, m, 28, eg). Above all, participants in the noninteractive condition wanted to understand why Stefan acts the way he does. They posed the question of “free will” (p10, f, 24, cg) and wanted to know who guided Stefan and influenced his actions. Those in the interactive condition, on the other hand, thought about the decisions made for the movie plot and the characters during the reception. They immediately saw the consequences of their decisions and pursued the goal of accompanying him as best they could on his path: The findings clearly show that interactivity is closely linked to deeper reflection and life evaluation (Research Question 1). Discussion This study investigated mental processes during the reception and subsequent entertainment experiences after an interactive or noninteractive narrative. Through a mixed-methods approach, we aimed to map cognitive and emotional processes during the reception and explain hypothesized differences between conditions. The results demonstrate that interactive narratives, compared with noninteractive ones, can increase viewers’ transportation, identification, enjoyment, and appreciation (Hypothesis 1a, b, c, and d). Our results align with previous research that also found interactive versions to facilitate the entertainment experience and various dimensions (Green & Jenkins, 2014; Hand & Varan, 2008). The qualitative results illustrate this connection impressively. They give insights into mental processes related to differences in entertainment experiences between the interactive and the noninteractive condition. Compared with participants in the noninteractive condition, participants in the interactive condition are clearly more involved in the entire reception process and direct their focus more on the main character, for whom they make decisions, than on other aspects (e.g., the visual design of the film). Results assume that interactivity made participants elaborate on how to decide for the protagonist. Participants seemed to identify with him more and reflect on what actions and decisions would be best for him. They feel very close to him, want to choose the best possible way for him, and help him. To achieve these goals, they join in the excitement with the protagonist and reflect on This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. INTERACTIVE DECISION-MAKING IN ENTERTAINMENT MOVIES decisions made and their moral consequences. This result is mirrored in findings of increased agency when watching Bandersnatch (Roth & Koenitz, 2019). In line with our quantitative results, participants of the interactive condition showed a deeper reflection of the narrative’s content and drew parallels to their own lives (How would they decide for themselves if they were in a similar situation?; Research Question 1). Furthermore, the data revealed differences in the focus of attention between both conditions: Whereas in the noninteractive condition, participants reported a stronger focus on the evaluation of the movie as a whole, in the interactive condition, the focus lay more on the protagonist and the decision-making process. The fact that this evaluation could be freely articulated in the reflective interviews is a main advantage of the chosen methodological approach. It becomes clear that the interactive condition enables the viewers to immerse themselves and reflect more deeply so that the boundaries to reality become partially blurred. In light of studies that found interactive narratives to increase donation intentions (Steinemann et al., 2015, 2017), future studies could consider this finding a potential starting point. They could investigate whether interactive choices can then promote other media effects, such as enhancing empathy for certain characters (Bartsch et al., 2018), facilitating recovery (Rieger et al., 2014, 2015), or behaving more morally (Oliver et al., 2012), to name a few. A further look at the correlation table (Table 2) confirms the qualitative findings and indicates that identification with the protagonist Stefan and transportation during the reception correlated with a deeper reflection of the film’s content and the reference to one’s own life. Both were further positively related to suspense, enjoyment, and appreciation. The perception of purpose, personal growth, and autonomy portrayed in a movie and a deeper reflection about relatedness with the protagonist and the activation of central values through a movie stimulus seem to play a role in the entertainment experience, especially in interactive movies. These results shed light on how interactivity fosters such experiences through a stronger bond with the characters. Through the decisions made for the character, there is a more substantial melting of the viewer and character perspective (apparent though a higher rating of deeper reflection). These can intensify enjoyment and, even more so, the appreciation of the entertainment offering. Taken together, the findings of this study can be regarded as a first step to investigate the potential of interactive stories with a multimethodological approach: As suggested in theories about the positive possibility of entertainment fare, for example, within the TEBOTS framework (Temporarily Expanding the Boundaries of the Self; Slater et al., 2014), the recovery and resilience in entertaining media use model (Reinecke & Rieger, 2021), or the notion of selftranscendence (Oliver et al., 2018), specific processes triggered by meaningful entertainment stimulate real-world consequences. Interactivity can play a vital role in this relationship—fostering identification with characters and an active role in the decisionmaking process, thereby “feeling” the decision and reflecting own life decisions. Concerning issues that limit the generalizability of our results, we would like to emphasize that our study consists of a very small sample (N = 60)—in quantitative terms. We chose this sample size mainly to give justice to the mixed-methods approach; the sample size is considerable for a qualitative setting. The qualitative study pursued the goal of theoretical saturation (Boddy, 2016; Saunders 7 et al., 2018), which could be achieved because further participants would not have provided new insights into the reception process. Patterns and similarities between the participants of the interactive and noninteractive conditions became apparent. Moreover, we need to discuss our findings in light of internal and external validity regarding the stimulus we used. Participants in both saw the first approximately 30 up to 40 min of Bandersnatch. At the beginning of the movie, decisions made are not crucial for the narrativity of the story. Although this decision helps to keep the content relatively similar and leads to similar stories in the interactive and noninteractive condition, it also means that more existential questions could overwhelm participants (especially under time pressure). We could not measure such reactions because the later parts of the movie were not shown to participants. Furthermore, this predefined interruption may also cause an interruption of entertainment experiences. Future research might want to assess variables such as continuation desire (SchoenauFog, 2011) to ensure the artificial interruption has no biasing impact on results. Regarding external validity, we need to point out that there are yet no comparable interactive movies released in the years that have passed since the release of Bandersnatch. Our findings are therefore hardly replicable by a lack of opportunistic movies. The results, however, can be taken into account especially when considering interactive features in meaningful entertainment that poses challenges to viewers. Still, we believe that our results might inform researchers and movie developers to improve interactive films’ design further and research the cognitive, emotional, and motivational effects of using them in the future. As the last limitation, our study investigates mental processes taking place during the reception. However, we attempt to access these processes through reflective interviews immediately after reception. In future studies, this design could be complemented with real process-oriented measurements such as psychophysiology to assess emotional and cognitive arousal (Potter & Bolls, 2012), real-time-response measurement (Reinemann et al., 2005), or even concurrent think-aloud to evaluate thoughts and feelings in situ (van den Haak et al., 2003). Conclusion This study provides insights into mental processes during the reception of interactive and noninteractive entertainment media. Participants in the interactive condition made decisions on the movie’s plot, whereas those in the noninteractive condition watched passively. In interactive narratives, viewers reflected the story deeper because they had sympathy and identified with movie characters. This way, as our results demonstrate, interactive narratives can intensify entertainment experiences. References Adachi, P. J. C., Ryan, R. M., Frye, J., McClurg, D., & Rigby, C. S. (2018). I can’t wait for the next episode!” Investigating the motivational pull of television dramas through the lens of self-determination theory. Motivation Science, 4(1), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000063 Appel, M., Gnambs, T., Richter, T., & Green, M. C. (2015). The Transportation Scale–Short Form (TS–SF). Media Psychology, 18(2), 243–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.987400 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 8 RIEGER, WULF, RIESMEYER, AND RUF Bartsch, A., & Hartmann, T. (2017). The role of cognitive and affective challenge in entertainment experience. Communication Research, 44(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214565921 Bartsch, A., Oliver, M. B., Nitsch, C., & Scherr, S. (2018). Inspired by the Paralympics: Effects of empathy on audience interest in para-sports and on the destigmatization of persons with disabilities. Communication Research, 45(4), 525–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215626984 Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research, 19(4), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053 Bosshart, L., & Macconi, I. (1998). Defining “entertainment”. Communication Research Trends, 18(3), 3–6. Bowman, N. D., Oliver, M. B., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B., Woolley, J., & Chung, M. Y. (2016). In control or in their shoes? How character attachment differentially influences video game enjoyment and appreciation. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, 8(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10 .1386/jgvw.8.1.83_1 Busselle, R., & Bilandzic, H. (2008). Fictionality and perceived realism in experiencing stories: A model of narrative comprehension and engagement. Communication Theory, 18(2), 255–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1468-2885.2008.00322.x Chung, D. S., & Yoo, C. Y. (2008). Audience motivations for using interactive features: Distinguishing use of different types of interactivity on an online newspaper. Mass Communication and Society, 11(4), 375–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430701791048 Christy, K. R., & Fox, J. (2016). Transportability and presence as predictors of avatar identification within narrative video games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(4), 283–287. https://doi.org/ 10.1089/cyber.2015.0474 Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with mass characters. Mass Communication and Society, 4(3), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01 Creswell, J. (2014). Research design (4th ed.). Sage. Crutcher, R. J. (1994). Telling what we know: The use of verbal report methodologies in psychological research. Psychological Science, 5(5), 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00619.x Elson, M., Breuer, J., Ivory, J. D., & Quandt, T. (2014). More than stories with buttons: Narrative, mechanics, and context as determinants of player experience in digital games. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 521–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12096 Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 Gläser, J., & Laudel, G. (2013). Life with and without coding: Two methods for early-stage data analysis in qualitative research aiming at causal explanations. Forum Qualitative Social Research, 14(2), Article 1886. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-14.2.1886 Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701 Green, M. C., Brock, T. C., & Kaufman, G. F. (2004). Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds. Communication Theory, 14(4), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885 .2004.tb00317.x Green, M. C., & Jenkins, K. M. (2014). Interactive narratives: Processes and outcomes in user-directed stories. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 479–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12093 Hand, S., & Varan, D. (2008). Interactive narratives: Exploring the links between empathy, interactivity, and structure. In M. Tscheligi, M. Obrist, & A. Lugmayr (Eds.), Changing television environments (pp. 11–19). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-69478-6_2 Hartmann, T. (2013). Media entertainment as a result of recreation and psychological growth. In E. Scharrer & A. Valdivia (eds.), Media effects/media psychology, Vol. 5. The international encyclopedia of media studies (pp. 170–188). Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10 .1002/9781444361506 Hofer, M. (2013). Appreciation and enjoyment of meaningful entertainment. The role of mortality salience and search for meaning in life. Journal of Media Psychology, 25(3), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1027/ 1864-1105/a000089 Kiousis, S. (2002). Interactivity: A concept explication. New Media and Society, 4(3), 355–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144480200400303 Mann, S. (2016). The research interview. Reflective practice and reflexivity in research processes. Palgrave. Moyer-Gusé, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18(3), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468 -2885.2008.00328.x Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., Moran, M. B., & Patnoe-Woodley, P. (2011). Involved, transported, or emotional? Exploring the determinants of change in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in entertainment-education. Journal of Communication, 61(3), 407–431. https://doi.org/10 .1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01554.x Neon. (2019). “Black Mirror—Bandersnatch”: Netflix lässt User über Schicksal von Filmfigur entscheiden—alle sind total überfordert [“Black Mirror—Bandersnatch”. Netflix lets users decide the fate of film characters - everyone is totally overwhelmed]. https://www.stern.de/neon/ feierabend/film-streaming/black-mirror-bandersnatch-interaktiver-netflixfilm-ueberfordert-zuschauer-8513416.html Netflix. (2017). Interaktive Geschichten auf Netflix: Der Zuschauer bestimmt, wie es weitergeht [Interactive stories on Netflix: The viewer decides what happens next]. https://media.netflix.com/de/company-blog/ interactive-storytelling-on-netflix-choose-what-happens-next Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2010). Appreciation as audience response. Exploring entertainment gratifications beyond hedonism. Human Communication Research, 36(1), 53–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958 .2009.01368.x Oliver, M. B., Bowman, N. D., Woolley, J. K., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B. I., & Chung, M. Y. (2016). Video games as meaningful entertainment experiences. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(4), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000066 Oliver, M. B., Hartmann, T., & Woolley, J. K. (2012). Elevation in response to entertainment portrayals of moral virtue. Human Communication Research, 38(3), 360–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958 .2012.01427.x Oliver, M. B., Raney, A. A., Slater, M. D., Appel, M., Hartmann, T., Bartsch, A., Schneider, F. M., Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Krämer, N., Mares, M.-L., Vorderer, P., Rieger, D., Dale, K. R., & Das, E. (2018). Self-transcendent media experiences: Taking meaningful media to a higher level. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 380–389. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/joc/jqx020 Oliver, M. B., & Raney, A. A. (2011). Entertainment as pleasurable and meaningful: Identifying hedonic and eudaimonic motivations for entertainment consumption. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 984–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01585.x Parrott, S., Carpentier, F. R. D., & Northup, C. T. (2017). A test of interactive narrative as a tool against prejudice. Howard Journal of Communications, 28(4), 374–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2017.1300965 Pessoa, A. S. G., Harper, E., Santos, I. S., & Gracino, M. C. D. S. (2019). Using reflexive interviewing to foster deep understanding of research participants’ perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918825026 Pfaff-Rüdiger, S., & Riesmeyer, C. (2016). Moved into action. Media literacy as social process. Journal of Children and Media, 10(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2015.1127838 Potter, R. F., & Bolls, P. (2012). Psychophysiological measurement and meaning: Cognitive and emotional processing of media. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203181027 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. INTERACTIVE DECISION-MAKING IN ENTERTAINMENT MOVIES Ratan, P. (2019). Just watched #Bandersnatch. Or did I play it? Was it a game? Anyway, my life won't be the same ever again! https://twitter .com/cule_uncool/status/1135272590795202560 Reinecke, L., Vorderer, P., & Knop, K. (2014). Entertainment 2.0? The role of intrinsic and extrinsic need satisfaction for the enjoyment of Facebook use. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 417–438. https://doi .org/10.1111/jcom.12099 Reinecke, L., Klatt, J., & Krämer, N. C. (2011). Entertaining media use and the satisfaction of recovery needs: Recovery outcomes associated with the use of interactive and non-interactive entertaining media. Media Psychology, 14(2), 192–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2011.573466 Reinecke, L., & Rieger, D. (2021). Media entertainment as a self-regulatory resource: The recovery and resilience in entertaining media use (R2EM) Model. In P. Vorderer & C. Klimmt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of entertainment theory (pp. 755–780). Oxford University Press. Reinemann, C., Maier, J., Faas, T., & Maurer, M. (2005). Reliabilität und Validität von RTR-Messungen [Reliability and validity of real-timeresponse measurements]. Publizistik, 50(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10 .1007/s11616-005-0118-4 Rieger, D., Reinecke, L., Frischlich, L., & Bente, G. (2014). Media entertainment and well-being-linking hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experience to media-induced recovery and vitality. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 456–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12097 Rieger, D., Frischlich, L., Wulf, T., Bente, G., & Kneer, J. (2015). Eating ghosts: The underlying mechanisms of mood repair via interactive and non-interactive media. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 4(2), 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000018 Rieger, D., Reinecke, L., & Bente, G. (2017). Media-induced recovery: The effects of positive versus negative media stimuli on recovery experience, cognitive performance, and energetic arousal. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000075 Rieger, D., Wulf, T., Kneer, J., Frischlich, L., & Bente, G. (2014). The winner takes it all: The effect of in-game success and need satisfaction on mood repair and enjoyment. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.037 Roth, C., & Koenitz, H. (2019, June). Bandersnatch, yea or nay? Reception and user experience of an interactive digital narrative video. In TVX’19, Proceedings of the 2019 ACM international conference on interactive experiences for TV and online video (pp. 247–254). ACM Digital Library. https://doi.org/10.1145/3317697.3325124 Roulston, K. (2010). Reflective interviewing: A guide to theory and practice. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288009 Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003066X.55.1.68 Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 52(4), 1893–1907. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 Schneider, S., Nebel, S., Beege, M., & Rey, G. D. (2018). The autonomyenhancing effects of choice on cognitive load, motivation and learning with digital media. Learning and Instruction, 58, 161–172. https://doi .org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.06.006 9 Schoenau-Fog, H. (2011, November). Hooked!–evaluating engagement as continuation desire in interactive narratives. International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling (pp. 219–230). Springer. Schramm, H., & Hartmann, T. (2008). The PSI-Process Scales. A new measure to assess the intensity and breadth of parasocial processes. Communications, 33(4), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMM.2008.025 Slater, M. D., Johnson, B. K., Cohen, J., Comello, M. L. G., & Ewoldsen, D. R. (2014). Temporarily expanding the boundaries of the self: Motivations for entering the story world and implications for narrative effects. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/ jcom.12100 Steinemann, S. T., Mekler, E. D., & Opwis, K. (2015, October). Increasing donating behavior through a game for change: The role of interactivity and appreciation. Proceedings of the 2015 annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play (pp. 319–329). ACM Digital Library. Steinemann, S. T., Iten, G. H., Opwis, K., Forde, S. F., Frasseck, L., & Mekler, E. D. (2017). Interactive narratives affecting social change. A closer look at the relationship between interactivity and prosocial behavior. Journal of Media Psychology, 29(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1027/ 1864-1105/a000211 Tamborini, R., Bowman, N. D., Eden, A., Grizzard, M., & Organ, A. (2010). Defining media enjoyment as the satisfaction of intrinsic needs. Journal of Communication, 60(4), 758–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1460-2466.2010.01513.x Tamborini, R., Grizzard, M., Bowman, N. D., Reinecke, L., Lewis, R. J., & Eden, A. (2011). Media enjoyment as need satisfaction. The contribution of hedonic and non-hedonic needs. Journal of Communication, 61(6), 1025–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01593.x van den Haak, M., de Jong, M. D. T., & Schellens, P. J. (2003). Retrospective vs. concurrent think-aloud protocols: Testing the usability of an online library catalogue. Behaviour & Information Technology, 22(5), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/0044929031000 van’t Riet, J., Meeuwes, A. C., van der Voorden, L., & Jansz, J. (2018). Investigating the effects of a persuasive digital game on immersion, identification, and willingness to help. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 40(4), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2018.1459301 Vorderer, P. (2011). What’s next? Remarks on the current vitalization of entertainment theory. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 23(1), 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000034 Vorderer, P., Knobloch, S., & Schramm, H. (2001). Does entertainment suffer from interactivity? The impact of watching an interactive TV movie on viewers’ experience of entertainment. Media Psychology, 3(4), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0304_03 Vorderer, P., Klimmt, C., & Ritterfeld, U. (2004). Enjoyment: At the heart of media entertainment. Communication Theory, 14(4), 388–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00321.x Wirth, W., Hofer, M., & Schramm, H. (2012). Beyond pleasure: Exploring the eudaimonic entertainment experience. Human Communication Research, 38(4), 406–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01434.x Received June 5, 2021 Revision received February 11, 2022 Accepted February 23, 2022 n