Family Relations - 2022 - Kim - A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of the TYRO Dads Program

advertisement

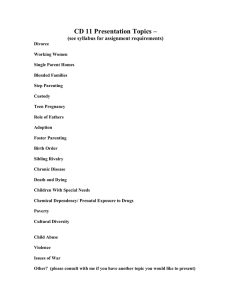

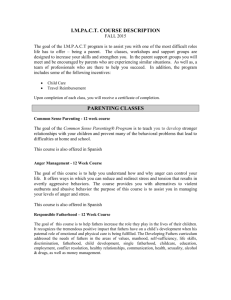

Received: 26 June 2018 Revised: 12 May 2021 Accepted: 16 May 2021 DOI: 10.1111/fare.12641 RESEARCH A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of the TYRO Dads Program Young-Il Kim1 | Sung Joon Jang2 1 College of Social Work, George Fox University, Newberg, Oregon, United States 2 Program on Prosocial Behavior, Institute for Studies of Religion, Baylor University, Waco, Texas, United States Correspondence Young-Il Kim, College of Social Work, George Fox University, 414 N. Meridian St. #6127, Newberg, OR 97132. Email: ykim@georgefox.edu Funding information This study was funded by the Fatherhood Research & Practice Network (FRPN). The FRPN is supported by Grant Number 90PR0006 from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The study was also supported in part by the George Fox University Grant GFU2018-19L04. Abstract Objective: To examine whether fathers who attend TYRO Dads class report greater satisfaction in their relationship with their child and increased engagement in activities with their child than nonparticipants and, if so, whether parenting efficacy, parenting role identity, and coparenting relationship with the child’s mother account for differences in father involvement between the intervention and control groups. Background: Despite the growing number of fatherhood intervention programs, limited experimental research has been conducted to evaluate their effectiveness. Method: A randomized controlled trial was conducted with a sample of 252 fathers randomly assigned to intervention and control groups. Both groups completed a pretest survey and were followed up at the end of intervention (posttest) and 3 months after the intervention (follow-up). Latent growth curve models were used to estimate both intervention and dosage effects. Results: The intervention group fathers reported significant improvement over time in the level of satisfaction of the relationship with their child. This finding may be partly because program participants became more confident in their parenting role, had their parenting role identity enhanced, or felt better about their relationship with their child’s mother. These results were more pronounced among those who attended eight out of 10 sessions. Conclusion: In this study, the TYRO Dads program was an effective intervention helping low-income fathers boost their confidence as a father and enhancing fathers’ perception of their relationship with the child’s mother. Implications: Responsible fatherhood programs should make an intentional effort to incentivize participation to increase attendance and the likelihood of completing the program. © 2022 National Council on Family Relations. Family Relations. 2023;72:271–293. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/fare 271 KEYWORDS coparenting, fatherhood, parenting efficacy, parenting role identity, TYRO Dads A consensus about the importance of fathers’ caregiving role has been growing over the past three decades (LaRossa, 1988; Schoppe-Sullivan & Fagan, 2020). Low-income fathers, however, face significant barriers to meeting the caregiving needs of their children, let alone fulfilling the role of financial provider. Too many low-income fathers may struggle with stable housing (Western & Smith, 2018), live in multiple households with multiple partners and children (Edin & Nelson, 2013; Guzzo, 2014), and have had experiences with the criminal justice system (Adams, 2018), all of which are detrimental to effective parenting. As a result, lowincome fathers tend to lack commitment to both their paternal identity and confidence in their parenting skills. These fathers can also experience difficulty in working together with the mother of the child, which has been identified as one of the strongest barriers to fathers’ involvement in parenting (Carlson et al., 2011). Despite such obstacles, however, many of these fathers desire to support their children financially and emotionally (Randles, 2020). Because of the important consequences for children’s well-being, addressing the needs of low-income fathers is crucial (McLanahan et al., 2013). For this reason, the federal government has funded several community-based fatherhood programs as part of the implementation of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (Berger & Carlson, 2020). In the newest round of grants, Administration for Children and Families (ACF; 2015) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funded 91 organizations in 27 states to provide activities to help low-income fathers strengthen their relationships with their child and the mother of the child. Although myriad fatherhood programs, including those funded by the ACF, have existed since the implementation of the act, a fundamental question has been neglected: Do fathers improve their relationships with their children and the mothers of their children as a consequence of the fatherhood program? Answering this causal question requires an experimental design in which participants are randomly assigned to either an intervention or control group. Previous research, however, was mostly conducted without a control group, or, when a control group was included in research design, assignment to groups was not completed by a random assignment procedure, leaving the true effect of the intervention uncertain (Osborne et al., 2014). Attempts to address these concerns have recently led to several large-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies (Avellar et al., 2018; Hayward et al., 2019; Sarfo, 2018). A recent meta-analysis, which reviewed some of those studies, reported small but statistically significant positive effects for father involvement, parenting, and coparenting (Holmes et al., 2020). For example, one study, which evaluated four fatherhood programs in the Midwest, reported a greater increase in nurturing behavior and involvement in child activities (Avellar et al., 2018). Another study evaluated a Baltimore fatherhood program and found that intervention group fathers showed greater involvement in their children’s lives than those in the control group (Sarfo, 2018). The present study extends the current fatherhood RCT literature in two ways. First, we not only examine intervention effects but also seek to identify the underlying mechanisms responsible for the effects using several mediating factors: parenting efficacy, parenting role identity, and father–mother coparenting relationship quality. To our knowledge, no RCT study has identified mediating mechanisms that explain the difference in parenting outcomes between intervention and control groups. Second, we use a three-wave panel design to track changes in the outcomes of interest over a 4-month period of study. Again, this is the first RCT study in this field showing the trajectory of outcome variables using growth curve modeling. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License FAMILY RELATIONS 272 273 INTERVENTION The TYRO Dads program (TYRO, henceforth) is a 20-hour course delivered in 10 2-hour sessions over a 5-week period. Since 2006, TYRO has been run by The RIDGE Project in Ohio, which was founded by Ron and Catherine Tijerina in 2000, based on their experience with Ron’s own 15-year incarceration. The RIDGE Project implements TYRO primarily with incarcerated fathers, with approximately 85% of program completions occurring in prisons, jails, and community corrections centers in Ohio. Since 2011, TYRO has also been implemented with nonincarcerated fathers—a group we intend to study. TYRO is built on the premise that when a father embraces the importance of his fatherhood role, he is motivated to change and do what is right for his children and family. It is designed also to increase fathers’ self-awareness and expand fathers’ view of what is possible for themselves and their families. These values are constantly reinforced throughout the workshop as every workshop begins by reciting the TYRO Declaration that includes several statements beginning with the words “I AM”: “I AM A TYRO. I AM a father. I AM a man of honor … I do not embarrass my family nor do I cause them pain and suffering … I AM a man of integrity … I AM trustworthy … I AM a leader. I AM a man worth following. I AM A TYRO!” (The RIDGE Project, n.d.). Through these activities, fathers who participate in the program are likely to learn the importance of various roles they ought to play as father (e.g., meeting emotional as well as physical and financial needs), which would enhance their confidence as a father. TYRO also stresses the importance of communication and conflict management skills that should enhance the ability of fathers to work together with the mother of their children as parents. In addition, participating fathers are expected to be resilient when they face difficulties in parenting. TYRO is instructed by facilitators, who are recruited from the community and complete a 16-hour training to learn how to deliver workshops effectively. The facilitators use a detailed instructional manual to present lessons and activities in each workshop. Participating fathers complete a workbook with key points and questions to be answered for each workshop. The workbook has space for notes, workshop exercises, and a list of homework assignments. TYRO culminates with a completion ceremony in which participating fathers are awarded a certificate of completion and a TYRO pin. This ceremony reinforces the father’s new identity as TYRO, “a man of honor and integrity” who embraces his role as father and is committed to doing what is right for his children and family. TYROs are further encouraged to join the TYRO Alumni Community for support, encouragement, and accountability. Fathers who attend a minimum of eight of the 10 classes receive a certificate of completion that ultimately enables them to access Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) funding for certain types of training, such as the Commercial Driver’s License. Those who complete TYRO also receive case management services to connect them to community services (e.g., legal aid, substance abuse counseling) needed to help them overcome challenges to employment and developing healthy and stable family relationships. CURRENT STUDY Intervention Effects The current study mainly evaluates the effectiveness of TYRO in improving the quality of the father’s relationship with his child, and we consider the following variables as our primary outcomes: fathers’ satisfaction in their relationship with their child and the frequency of fathers doing things together with their child or, in short, father–child activities. Attachment theory provides a conceptual basis for our primary outcomes. The theory posits that a father’s 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS sense of closeness to his child and sensitivity to the child’s social and emotional needs increase father–child interactions (Paquette, 2004). To the extent that the program is successful in encouraging fathers to develop strong attachments with their child, fathers who participate in the program are expected to report more satisfaction with their relationship with their child than those in a control group. In addition, participating fathers are expected to do things together with their children more often than their nonparticipating counterparts. Hence, we hypothesize as follows: Hypothesis 1a: Fathers who attend TYRO are more likely to show an increase in their satisfaction with their relationship with the child over time than those who do not. Hypothesis 1b: Fathers who attend TYRO are more likely to show an increase in the frequency of father–child activities over time than those who do not. Drawing on identity theory and family systems theory, we evaluate the effectiveness of TYRO in terms of improvement in three secondary outcomes of the program: parenting efficacy (Freeman et al., 2008), parenting role identity (Rane & McBride, 2000), and the father’s perception of coparenting relationship with the child’s mother (Fagan & Palkovitz, 2011)—all of which are emphasized in the TYRO curriculum. First, according to identity theory, an individual’s self is a hierarchy of identities in terms of status (e.g., father) and role (e.g., provider), and more prominent central identities are more likely to affect the individual’s behaviors than are others (Pasley et al., 2014; Stryker & Serpe, 1994). Therefore, to the extent that the program is effective in helping fathers strengthen their paternal identity, intervention group fathers are expected to report greater increase in parenting efficacy and role identity. To test intervention effects for coparenting relationships, we draw on family systems theory, which emphasizes interdependence of the family’s subsystems (i.e., father–child, mother–child, and father–mother relationships). The theory stresses the significance of the father–mother relationship, especially the coparenting relationship, in improving the father–child relationship (Cox et al., 2001; Stevenson et al., 2014). Thus, we expect that attending TYRO will improve fathers’ perception of coparenting. Taken together, we hypothesize the following: Hypothesis 2. Fathers who attend TYRO are more likely to show an increase in parenting efficacy, parenting role identity, and coparenting relationship with the child’s mother over time than those who do not attend the program. Mediation Effects We examine these secondary outcomes not only because they are important aspects of parenting but also because we believe they help explain why participation in TYRO is likely to increase fathers’ involvement in parenting. Thus, we test whether the secondary outcomes account for differences in the primary outcomes between the intervention and control groups. Hypothesis 3. Fathers who attend TYRO are more likely to show an improvement in parenting efficacy, parenting role identity, and coparenting relationship, which in turn increases satisfaction with their relationship with the child and the frequency of father–child activities, than those who do not attend the program. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License FAMILY RELATIONS 274 275 Dosage Effects In addition to examining program effectiveness by comparing outcomes between the intervention and control groups, we evaluate dosage effects, which is receiving more attention in the fatherhood research field (for a review, see Fagan & Pearson, 2020). We measured dosage levels by attendance and compared outcomes for fathers in the intervention group whether they attended at least eight sessions—the required minimum number of sessions for program completion. We expect the effect of TYRO to be greater among fathers who attend more sessions than those who attend fewer or none. In doing so, we can determine whether the minimum attendance required by RIDGE is a key threshold for reaping the full benefit of the program. METHOD Study Design We used an RCT design to evaluate the effectiveness of TYRO in improving the father–child relationship outcomes among low-income fathers in Ohio. TYRO was offered throughout the year, and the RIDGE allowed us to implement our study to new cohorts of clients at 17 sites across nine cities (Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Lima, Mansfield, Toledo, and Wooster). Some cities had multiple sites (e.g., Cleveland), although others had one (e.g., Canton). A total of six facilitators were involved in this study, and each course was led by a single instructor except at one site in Dayton. The RIDGE headquarters trained facilitators of all sites for data collection and research procedures. The study protocol and instrument were approved by Baylor University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB Reference # 679364) in January 2015, and data were collected between February 2015 and September 2016 at each site at three time points: baseline (pretest), immediately after the intervention (posttest), and 3 months after the intervention (follow-up). Pretest survey Baseline assessment was administered at an orientation meeting, where randomized participating fathers were invited to complete a pretest survey before the first session of the class. All fathers eligible for the study were notified via mail of the time and location of the orientation. Both intervention and control group fathers participated in the baseline assessment after which they were informed about group assignment. Posttest survey Immediate postintervention assessment was administered to intervention group fathers at the end of the last class session. Fathers in the intervention group were reminded of the time and location of posttest survey administration in Class Sessions 8 and 9. Facilitators at each location administered the survey following a predetermined protocol. The control group fathers participated in the posttest survey over the phone by a trained interviewer. Follow-up survey Approximately 3 months after the posttest survey, the interviewer called all fathers in both groups and conducted telephone interview for a follow-up survey. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS FAMILY RELATIONS Sample Size To obtain a sample that would enable us to detect a difference between intervention and control groups, we conducted power analysis that applied a small-to-medium effect size (.30) and expected attrition rate (20%) based on prior research (Cowan et al., 2009; Rienks et al., 2011) for three correlations of outcomes between time points: low (.25), medium (.50), and high correlation (.75). Our analysis revealed that we would need 172 per group (a total of 344) at baseline after adjusting for an attrition rate of 20%. Although our baseline sample (n = 252) was smaller than the target sample size, attrition analysis revealed generally no significant difference in sociodemographic characteristics among fathers who participated in the pretest, posttest, and follow-up surveys with only a few exceptions (see Appendix S1 for the details of attrition analysis). Participants Eligibility criteria for study participants included being a man who was 18 years old or older, a father of at least one biological child under age 19 years, and having a household income at or below 200% of the federal poverty level. The study participants were recruited from a variety of settings, including child support enforcement agencies, job and family services, organizations serving individuals with mental or behavioral health needs, organizations serving individuals with drug or alcohol addiction, probation and parole, courts, reentry coalitions, Head Start, and one-stop employment agencies. At these organizations, flyers and sign-up forms for this study were posted along with TYRO applications. In addition, the TYRO facilitators actively recruited at the locations where the classes were held. Individuals interested in participating in this study sent their completed application and sign-up form to the RIDGE headquarters office. At the initial screening stage, staff at the RIDGE regional offices screened applicants and emailed a list of those eligible for this study to the principal investigator for random assignment of eligible fathers to intervention and control groups before the pretest. Participation Flow Figure 1 shows how the number of participants changed throughout the study period. A total of 525 fathers were recruited and assessed for eligibility, and 469 fathers met the entry criteria and were randomly assigned to intervention (n = 257) and control (n = 212) groups. However, 217 of them (120 in the intervention group and 97 in the control group) did not show up for the baseline assessment, which resulted in 252 completion of the baseline assessment (137 in the intervention group and 115 in the control group). Subsequently, 177 (87 in the intervention group and 90 in the control group) and 140 fathers (81 in the intervention group and 59 in the control group) completed the posttest and 3-month follow-up surveys, respectively. Eventually, a total of 120 fathers (65 in the intervention group and 55 in the control group) completed all three surveys, whereas the remaining 132 fathers participated in one or two surveys: 55 fathers who completed only the pretest, 57 who did only the pretest and immediate posttest, and 20 who did only the pretest and 3-month follow-up posttest (not shown in Figure 1). Randomization The principal investigator (PI) randomly assigned the participants to experimental and control groups at a 1:1 allocation ratio using a computer-generated list of random numbers (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The PI then sent the randomization list to the RIDGE headquarters 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 276 277 Assessed for eligibility (n = 525) Excluded (n = 56) Not meeting inclusion criteria (n = 56) Randomized (n = 469) Allocated to intervention (n = 257) Did not receive allocated intervention (n = 0) Allocated to control (n = 212) Did not receive allocated intervention (n = 0) Baseline Questionnaire returned (n = 137) No show-up (n = 120) Baseline Questionnaire returned (n = 115) No show-up (n = 97) Immediate follow-up (n = 87) Discontinued (n = 50) Immediate follow-up (n = 90) Discontinued (n = 25) 3-month follow-up (n = 81) Discontinued (n = 6) 3-month follow-up (n = 59) Discontinued (n = 31) Analyzed (n = 65) Excluded from analysis due to insufficient data (n = 16) Analyzed (n = 55) Excluded from analysis due to insufficient data (n = 4) FIGURE 1 Flow Diagram office in which a study coordinator prepared group assignment letters to study participants. For those assigned to the control group, a $20 gift card incentive was included in the envelope. The study coordinator then distributed the sealed envelopes to facilitators at research sites. The study participants gave informed consent and completed the baseline survey. After that, the facilitator handed out the sealed envelopes to the participants, and they learned their group assignment. Both the facilitators and the participants were blinded to the randomization. Measurement Satisfaction with one’s relationship with the child We used four items about how happy and satisfied the father was with his relationship with the child, how good the relationship was, and how close the father felt with the child. These items 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS FAMILY RELATIONS were taken from the NRI-Relationship Qualities Version (NRI-RQV; Furman & Buhrmester, 2009). They were all measured based on a 5-point Likert scale, although the content of response options differed among the items (i.e., 1 = not at all happy, 5 = extremely happy; 1 = not satisfied, 5 = extremely satisfied; 1 = not good, 5 = great; 1 = not at all close, 5 = extremely close). All items were loaded on a single factor with high loadings, ranging from .83 to .92 (pretest), from .78 to .89 (posttest), and from .85 to .88 (follow-up). Interitem reliability was excellent across the three waves (α = .92, .92, and .92). We constructed a scale of satisfaction with one’s relationship with the child by averaging the four items. When fathers had more than one biological child, they were asked to report about the youngest one. The frequency of father–child activities To measure fathers’ involvement in activities with their child, we employed multiple developmentally age-appropriate items, which was originally developed by the Fatherhood Research Practice Network (FRPN; Dyer et al., 2018). The items varied depending on the age of child: 19 items (12 months or younger), 26 items (older than 12 months but younger than 12 years old), and 24 items (12 years old or older). Some items were same across the age groups (e.g., How often have you had meals with the child?); other items were specific to each age group (e.g., How often have you changed diapers? [12 months or younger]; How often have you made sure that the child’s teeth were brushed? [older than 12 months but younger than 12 years old]; How often have you played or assisted the child with sports? [12 years old or older]). Each item was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = rarely or never and 5 = almost every day. For each age group, we constructed a scale of father–child activities by averaging the items at pretest, posttest, and follow-up. All factor loadings were higher than .50, and interitem reliability was excellent, ranging from .980 to .984 (the child 12 months old or younger), from .984 to .988 (the child older than 12 months but younger than 12 years old), and from .969 to .978 (the child 12 years old or older). Parenting efficacy To measure parenting efficacy, we used a scale developed by the FRPN. The items on this scale assess father’s perceived sense of control in providing parental care for child, such as “Helping the child when he/she is upset or distressed” and “Understanding what the child wants or needs” (1 = definitely not true, 4 = definitely true). Factor loadings ranged from .62 to .88 (pretest), from .70 to .91 (posttest), and from .84 to .92 (follow-up), and internal reliability was excellent at all surveys (α = .93, .94, .96). A scale of parenting efficacy was constructed by averaging the seven items. Parenting role identity Seven items were used to measure parenting role identity. Fathers were asked how important different parental roles were to them, for example, “being a good financial provider for my child,” “being always available to my child,” and “meeting my child’s physical and emotional needs” (1 = not at all important, 4 = extremely important). A scale of parenting role identity was constructed by averaging the seven items. Factor loadings were moderate to high, ranging from .51 to .80, from .57 to .89, and from .69 to .88, whereas interitem reliability was high to excellent (α = .87, .91, and .92). 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 278 279 Coparenting relationship with the child’s mother We used eight of 11 FRPN-validated Coparenting Relationship Scale items that measure the extent to which parenting partners trust each other and have quality communications between them (Cohen & Weissman, 1984). They tap the construct’s three dimensions—undermining (2 items), alliance (4 items), and gatekeeping (2 items; Dyer et al., 2018), using 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Exploratory factor analysis generated a twofactor solution, with the negative items of undermining and gatekeeping being loaded on one factor and the positive items of alliance on the other across all three surveys, and their loadings were all higher than .40. Because the two-factor solution was likely to be a methodological artifact (i.e., negative and positive items clustered separately) and the items had very high internal reliability at each survey (α = .90, .92, .89), we averaged all eight items to construct a scale of coparenting relationship. Background characteristics Father’s sociodemographic and criminal characteristics were drawn from fathers’ completed application form: age, race and ethnicity, education, income, marital status, household size (i.e., number of people in the household), prior incarceration, parole status, and prior conviction of sex offense. Analysis Plan We used latent growth curve modeling (Bollen & Curran, 2006) to evaluate the effectiveness of TYRO in improving father–child relationships over a 4-month of period. Figure 2 shows our F I G U R E 2 Latent Growth Curve Model of the Intervention Effect of TYRO on Primary (Fathers’ Satisfaction With Their Relationship With Their Child and Frequency of Father–Child Activities) and Secondary Outcome (Parenting Efficacy, Parenting Role Identity, and Coparenting Relationship) With Two Time-Invariant Covariates (Married and Household Size) 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS FAMILY RELATIONS latent growth curve model in which the repeated measures of outcome variables are specified as indicators of the intercept and slope growth factors. For the intercept factor, loadings from the factor to each of the repeated measures are fixed to values of 1.0, indicating that the factor equally affects all repeated measures across the surveys. For the slope factor, on the other hand, loadings are fixed to the values of 0, 1.0, and 4.0 to model a linear function of time, given that the posttest and 3-month follow-up were conducted 1 and 4 months after the pretest, respectively. The endogenous growth factors of intercept and slope were regressed on the key exogenous variable of intervention (0 = control group, 1 = intervention group) and the time-invariant covariates, which were correlated with one another. The model is a “conditional” model because it controls for the two time-invariant covariates in which our attrition analysis revealed the intervention and control group fathers were different: being married (vs. not married, whether never married, divorced, separated, cohabiting, or widowed) and household size. Although not shown in a figure, we analyzed dosage effects by replacing the dummy variable of group membership (0 = control group, 1 = intervention group) with three dummy variables to operationalize dosage: low (one to four sessions), medium (five to seven sessions), and high levels of class attendance (eight to 10 sessions), with no attendance (0 sessions) being the reference category. Control group fathers were coded as having attended 0 sessions. By doing so, we examined whether intervention group fathers who attended at least eight sessions were more likely to reap the benefit of the program than those who attended less than eight sessions as well as the control group fathers. Because most of this study’s measures are ordered categorical variables, the MLR estimator (maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors) of Mplus Version 8 was employed (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Further, Muthén’s (1983) general structural equation model and its full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation, incorporated into Mplus, allowed us to include not only continuous but also dichotomous and ordered polytomous variables in the model. To treat missing data, we applied FIML, which tends to produce unbiased estimates, like multiple imputations (Schafer & Graham, 2002). For data-model fit assessment, we use Hu and Bentler’s (1999) two-index presentation strategy, focusing on three fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). They found that using a cutoff value of .95 for CFI in combination with that of .08 for SRMR “resulted in the least sum of Type I and Type II error rates” (p. 28). The same was found when they replaced CFI with RMSEA using a cutoff value of .06. Thus, two combinational rules were used to evaluate model fit: (CFI ≥ .95 and SRMR ≤ .08) and (SRMR ≤ .08 and RMSEA ≤ .06). For statistical significance, a two-tailed test (α = .05) was conducted with a one-tailed test (α = .05) being applied as well when coefficients are in the hypothesized direction. RESULTS Sample Characteristics Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic and criminal characteristics of the total sample (n = 252) at the pretest, which consists of 115 fathers in the intervention group and 137 in the control group. On average, study participants were in their mid-30s, and more than two thirds of them had previously been incarcerated. A large majority of the participants were non-White, and two thirds or more of fathers were never married. On average, the participants live with two children in their household all or most of the time. The participants typically lived with two people in the same household that had an average annual income of approximately $6000 and had no high school diploma or GED. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 280 TABLE 1 281 Baseline Sociodemographic and Criminal Characteristics of the Fathers (N = 252) Control group n = 115 Experimental group n = 137 Variables M SD M SD p Age 35.09 10.86 34.44 10.61 .637 Ever incarcerated 0.72 0.45 0.68 0.47 .439 On parole 0.23 0.43 0.30 0.46 .310 Ever convicted of sex offense 0.05 0.22 0.05 0.22 .976 Hispanic 0.06 0.24 0.07 0.26 .782 Black 0.71 0.46 0.63 0.48 .209 White 0.24 0.43 0.32 0.47 .165 Other race 0.01 0.10 0.01 0.09 .852 Non-White 0.77 0.42 0.69 0.46 .183 Never married 0.73 0.45 0.66 0.48 .208 Married 0.08 0.27 0.16 0.37 .042 Divorced 0.19 0.40 0.16 0.37 .524 Widowed 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.15 .083 Cohabitation 0.16 0.36 0.12 0.32 .360 Number of people in the household 1.81 1.65 2.05 1.81 .275 Number of children in the household 1.92 1.35 2.06 1.81 .210 Household income ($1000 s) 5.90 15.78 5.93 10.94 .988 Personal income ($1000 s) 2.76 6.86 3.77 8.19 .326 Education 1.91 0.79 1.89 0.82 .844 Baseline comparisons between the intervention and control groups showed no significant difference except in marital status: Control group fathers were less likely to be married (7.8%) than intervention group fathers (16.1%, p = .042). We also found significant difference in the number of people living in the household between the groups when we analyzed for a subsample of fathers who participated in all three surveys (n = 120). Specifically, fathers in the control group reported living with a smaller number of people in their household (1.82) than the intervention group fathers (2.49, p = .01; not shown in the table). On the basis of this finding, we control for these two variables in the subsequent analyses. Program Dosage On average, intervention group fathers attended about half of the sessions (5.31) with a standard deviation of 3.80 sessions. Twenty-three (16.8%) of the 137 fathers in the intervention group did not attend even a single session, and, coincidentally, the same number of fathers (23, 16.8%) had perfect attendance (i.e., 10 sessions). The number of fathers who attended at least one session but less than the average was 36 (26.3%), whereas those who attended five to nine sessions was 55 (40.1%) with 24 (17.5%) of them missing just one session. About four out of 10 (56, 40.9%) intervention group fathers attended at least eight sessions. The average age of high-attending fathers (37.54) was older than that of the rest of the fathers (32.31). Using onetailed test (α = .05), the high attendance group was more likely to cohabit (18%) and had higher education (2.05) compared with the other groups combined (7% and 1.78, respectively). We found no difference, however, in criminal background, race and ethnicity, marital status (other than cohabitation), household size, and income. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS FAMILY RELATIONS Effect Size. Before testing our hypotheses about the effect of intervention on changes in parenting outcomes over time, we examined the effect in terms of Cohen’s (1992) d at the posttest (T2) and follow-up (T3) based on 10 (= 5 parenting outcomes 2 time points) mean comparisons between the intervention and control groups. The effect size was small (i.e., .20 or smaller) and not significant for fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with the child at T2 and T3 (d = .18 and .20, p > .05), frequency of father child activities at T2 and T3 (d = .01 and .02, p > .05), parenting efficacy at T2 (d = .12, p > .05), parenting role identity at T2 and T3 (d = .05 and .16, p > .05), and coparenting relationship at T2 (d = .20, p > .05). On the other hand, a small (.20) to medium (.50), significant effect size was found for parenting efficacy at T3 (d = .34, p < .05) and coparenting relationship at T3 (d = .41, p < .05). H1a and H1b: Improvement in Primary Outcomes in the Intervention Group To examine whether participation in TYRO increased the fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child (Hypothesis 1a) and involvement in activities with their child (Hypothesis 1b) over the 4-month period of evaluation, we estimated the latent growth model for the total sample (N = 252). Table 2 presents estimated intervention effects, whereas Table 3 shows results from the analysis of dosage effect. We found that CFIs were all higher than the cutoff of .95, and SRMRs were smaller than the cutoff of .08. RMSEAs were smaller than .06 with one exception (i.e., intervention effect for fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child), whereas the 90% confidence interval of RMSEA tended to include values larger than the cutoff of .06. In sum, all models were found to have a good fit to data, meeting one of the two joint criteria—that is, CFI ≥ .95 and SRMR ≤ .08. Intervention effects We found no intervention effect on the primary outcomes (see Table 2), as the effect of intervention on the slope factors of satisfaction with their relationship with their child and the frequency of father–child activities were not significant (B = 0.06, B = 0.04, p > .05). Dosage effects When we take dosage levels into account, significant effects were found for fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child (see Table 3). Specifically, the intervention effect for fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child was observed for the high-dosage (B = 0.09, p < .05) but not the low- or medium-dosage groups (B = 0.05 and B = 0.04, p > .05). No significant effect was observed for the frequency of father–child activities (B = 0.02, B = 0.04, B = 0.04, p > .05). In sum, Hypothesis 1a was supported only for dosage effects, and Hypothesis 1b received no support. H2: Improvement in Secondary Outcomes in the Intervention Group Next, we examined the intervention and dosage effects for the secondary outcomes. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 282 .02 SRMR .02 1.00 .00 [.00, .08] 2.86 [4, .581] (0.05) 0.23** (0.25) 0.41 (0.16) (0.01) 0.02 (0.07) 0.06 (0.05) 0.04 Slope .01 1.00 .00 [.00, .07] 1.94 [4, .757] (0.02) 0.05** (0.10) 0.01 (0.09) 0.02 Intercept (0.01) 0.01* (0.05) 0.00 (0.03) 0.06* Slope Parenting efficacy .01 1.00 .00 [.00, .08] 2.55 [4, .635] (0.07) 0.20** (0.09) 0.18** (0.05) 0.02 Intercept (0.07) 0.06 (0.08) 0.05 (0.02) 0.03 Slope Parenting role identity .02 1.00 .00 [.00, .09] 3.29 [4, .510] (0.03) 0.08** (0.16) 0.20 (0.09) 0.05 Intercept (0.01) 0.01 (0.04) 0.04 (0.03) 0.06** Slope Coparenting relationship 283 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Note. Unstandardized parameter estimates are presented with their standard errors in parentheses. CFI = comparative fit index; CI = confidence interval; FFA = frequency of father–child activities; RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation; SRC = satisfaction with one’s relationship with the child; SRMR = standardized root mean squared residual. * p < .05 (one-tailed test). ** p < .05 (two-tailed test). .98 .06 [.00, .13] CFI 7.95 [4, .093] (0.01) (0.04) RMSEA [90% CI] 0.00 0.18** 0.03 (0.06) 0.01 (0.21) χ2 [df, p value] Fit indices Household size Married 0.06 (0.04) 0.01 (0.15) Intervention 0.04 Intercept Intercept Slope FFA SRC Conditional Linear Latent Curve Models of Intervention Effects and Covariates on Parenting Outcomes (N = 252) Exogenous variables TABLE 2 TYRO DADS (0.01) (0.04) .01 CFI SRMR .02 1.00 .00 [.00, .06] 3.69 [6, .719] (0.05) 0.24** (0.24) 0.46* (0.20) 0.11 (0.30) 0.25 (0.24) 0.29 (0.01) 0.02 (0.07) 0.07 (0.06) 0.04 (0.11) 0.04 (0.08) 0.02 Slope .01 1.00 .00 [.00, .04] 2.56 [6, .862] (0.02) 0.05** (0.10) 0.02 (0.10) 0.04 (0.18) 0.14 (0.15) 0.06 Intercept (0.01) 0.01 (0.05) 0.01 (0.03) 0.07** (0.04) 0.04 (0.05) 0.05 Slope Parenting efficacy .02 1.00 .00 [.00, .07] 4.31 [6, .635] (0.01) 0.04** (0.09) 0.19** (0.07) 0.08 (0.09) 0.01 (0.07) 0.01 Intercept (0.01) 0.00 (0.03) 0.02 (0.03) 0.05* (0.04) 0.01 (0.03) 0.02 Slope Parenting role identity .02 .99 .04 [.00, .10] 8.73 [6, .189] (0.03) 0.09** (0.15) 0.24 (0.12) 0.10 (0.16) 0.23 (0.14) 0.22 Intercept (0.01) 0.01 (0.04) 0.04 (0.03) 0.08** (0.04) 0.05 (0.05) 0.10** Slope Coparenting relationship FAMILY RELATIONS 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Note. Unstandardized parameter estimates are presented with their standard errors in parentheses. CFI = comparative fit index; CI = confidence interval; FFA = frequency of father–child activities; RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation; SRC = satisfaction with one’s relationship with the child; SRMR = standardized root mean squared residual. * p < .05 (one-tailed test). ** p < .05 (two-tailed test). .02 [.00, .09] 1.00 RMSEA [90% CI] 6.95 [6, .325] 0.00 (0.06) (0.21) 0.18** 0.03 0.13 0.09** (0.04) 0.24 (0.05) (0.27) (0.19) 0.04 (0.06) 0.11 (0.22) χ2 [df, p value] Fit indices Household size Married 8–10 sessions attended 5–7 sessions attended 0.05 0.24 Intercept Intercept Slope FFA SRC Conditional Linear Latent Curve Models of Dosage Effects and Covariates on Parenting Outcomes (N = 252) 1–4 sessions attended Exogenous variables TABLE 3 284 285 Intervention effects Table 2 shows significant improvement among the intervention group fathers in parenting efficacy (B = 0.06, p < .05) and coparenting relationship with their child’s mother (B = 0.06, p < .05) but not in parenting role identity (B = 0.03, p > .05). Dosage effects Table 3 shows that the high-dosage group reported a significant increase not only in parenting efficacy (B = 0.07, p < .05) and coparenting relationship (B = 0.08, p < .05) but also in parenting role identity (B = 0.05, p < .05). In sum, Hypothesis 2 received partial support for two of the three secondary outcomes from the both intervention and dosage effects models. H3: Improvement in Primary Outcomes Mediated Through Secondary Outcomes Tables 4 through 7 show results from estimating models where the slope factors of secondary outcomes mediate the intervention effect of primary outcomes for the total sample minus 12 cases missing on all exogenous variables (N = 240). In each table, the first three columns indicate the effects of program participation and two control variables on the intercept and slope factors of mediators (coparenting relationship, parenting efficacy, and parenting role identity), whereas the last column shows the effects of the mediators as well as exogenous variables on the intercept and slope factors of fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child (Tables 4 and 6) and the frequency of father–child activities (Tables 5 and 7). T A B L E 4 Conditional Linear Latent Curve Models of the Effects of Intervention on Mediators (Coparenting Relationship, Parenting Efficacy, and Parenting Role Identity) and Fathers’ Satisfaction With Their Relationship with Their Child (N = 240) Exogenous variables Coparenting relationship Intercept Parenting efficacy Slope Parenting role identity SRC Intercept Slope Intercept Slope Intercept Slope Married 0.21 0.04 0.01 0.00 0.18 0.02 0.10 0.02 Household size 0.09** 0.01 0.05** 0.01 0.04** 0.00 0.08** 0.01 Intervention 0.04 0.07** 0.04 0.05 0.02 0.04 0.08 0.07 Coparenting relationship Intercept 0.61** Slope 0.90** Parenting efficacy Intercept 1.07** Slope 0.89** Parenting role identity Intercept Slope 0.27 1.15** Note. χ (55) = 124.36, p < .05; root mean squared error of approximation = .07; comparative fit index = .93; standardized root mean squared residual = .05. SRC = Satisfaction with one’s relationship with the child. The sample size is reduced from 252 to 240 due to 12 missing cases. * p < .05 (one-tailed test). ** p < .05 (two-tailed test). 2 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS T A B L E 5 Conditional Linear Latent Curve Models of the Effects of Intervention on Mediators (Coparenting Relationship, Parenting Efficacy, and Parenting Role Identity) and Frequency of Father–Child Activities (N = 240) Exogenous variables Coparenting relationship Intercept Parenting efficacy Slope Parenting role identity FFA Intercept Slope Intercept Slope Intercept 0.01 0.18 0.02 0.26 Slope Married 0.21 0.03 0.02 0.08 Household size 0.09** 0.01 0.05** 0.01 0.04** 0.00 0.18** 0.03 Intervention 0.05 0.06** 0.04 0.04 0.02 0.04 0.01 0.23** Coparenting relationship Intercept 0.15 Slope 0.89* Parenting efficacy Intercept 1.25** Slope 0.99** Parenting role identity Intercept 0.40 Slope 2.48** Note. χ (55) = 101.69, p < .05; root mean squared error of approximation = .06; comparative fit index = .94; standardized root mean squared residual = .06. FFA = Frequency of father–child activities. The sample size is reduced from 252 to 240 due to 12 missing cases. * p < .05 (one-tailed test). ** p < .05 (two-tailed test). 2 T A B L E 6 Conditional Linear Latent Curve Models of the Effects of Dosage on Mediators (Coparenting Relationship, Parenting Efficacy, and Parenting Role Identity) and Fathers’ Satisfaction With Their Relationship With Their Child (N = 240) Exogenous variables Married Coparenting relationship Intercept 0.26* Parenting efficacy Slope Parenting role identity SRC Intercept Slope Intercept Slope Intercept 0.04 0.03 0.01 0.18 0.02 0.11 Slope 0.01 Household size 0.09** 0.01 0.05** 0.01 0.04** 0.00 0.07** 0.02 1 0.26 0.11** 0.09 0.06 0.01 0.05 0.01 0.09 5–7 sessions attended 0.22 0.05 0.12 0.04 0.01 0.02 0.10 0.06 8+ sessions attended 0.11 0.09** 0.04 0.06* 0.07 0.05* 0.16 0.02 4 sessions attended Coparenting relationship Intercept 0.61** Slope 0.62 Parenting efficacy Intercept 1.13** Slope 1.69** Parenting role identity Intercept Slope 0.21 0.31 Note. χ (63) = 123.38, p < .05; root mean squared error of approximation = .07; comparative fit index = .94; standardized root mean squared residual = .04. SRC = satisfaction with one’s relationship with the child. The sample size is reduced from 252 to 240 due to 12 missing cases. * p < .05 (one-tailed test). ** p < .05 (two-tailed test). 2 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License FAMILY RELATIONS 286 287 T A B L E 7 Conditional Linear Latent Curve Models of the Effects of Dosage on Mediators (Coparenting Relationship, Parenting Efficacy, and Parenting Role Identity) and Frequency of Father–Child Activities (N = 240) Exogenous variables Coparenting relationship Intercept Parenting efficacy Slope Parenting role identity FFA Intercept Slope Intercept Slope Intercept Slope 0.03 0.04 0.01 0.18 0.02 0.30 0.10 0.02 Married 0.26* Household size 0.09** 0.01 0.05** 0.01 0.04** 0.00 0.18** 1 4 sessions attended 0.25 0.12** 0.07 0.06 0.02 0.05* 0.17 0.28** 5 7 sessions attended 0.23 0.05 0.11 0.03 0.02 0.02 0.38 0.16 0.10 0.08** 0.03 0.05 0.06 0.05* 0.02 0.31** ≥8 sessions attended Coparenting relationship Intercept 0.08 Slope 0.92* Parenting efficacy Intercept 1.30** Slope 1.00** Parenting role identity Intercept Slope 0.43 2.28** Note. χ (63) = 112.23, p < .05; root mean squared error of approximation = .06; comparative fit index = .94; standardized root mean squared residual = .06. FFA = frequency of father–child activities. The sample size is reduced from 252 to 240 due to 12 missing cases. * p < .05 (one-tailed test). ** p < .05 (two-tailed test). 2 Intervention effects In Table 4, the last column shows that the growth factors of mediators had positive effects on those of fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child (SRC) with one exception (i.e., the effect of parenting role identity’s intercept factor on SRC’s intercept factor, 0.27). The associations between slope factors of mediator and SRC are of key interest, and we found fathers, whose coparenting relationship, parenting efficacy, and role identity improved, tended to report increasing SRC (0.90, 0.89, and 1.15, respectively). In supplemental analysis, we tested the statistical significance of mediation effects (results available upon request), which confirmed that intervention had significant indirect effect on the slope factor of SRC via the slope factor of coparenting relationship (B = 0.06, p < .05) and parenting role identity (B = 0.04, p < .05) but not parenting efficacy (B = 0.04, p > .05). Table 5 shows that the intervention also had indirect effect on the frequency of father–child activities via one of the three mediators. Specifically, coparenting relationship, positively related to frequency of father–child activities (B = 0.89, p < .05) as well as the intervention (see Table 2), significantly mediated the relationship between the two variables (B = 0.06, p < .05; not shown in the table). Dosage effects Table 6 shows results from estimating the same model with different dosage levels. We see that only one of the slope factors was found to be positively associated with the slope factor of SRC: parenting efficacy (B = 1.69, p < .05). This result supports the significance of indirect effect (B = 0.10, p < .05; not shown), which we found was the only nonsignificant mediator in the intervention effects model. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS FAMILY RELATIONS Table 7 shows the slope factor of frequency of father–child activities was positively related to that of coparenting relationship, parenting efficacy, and parenting role identity (0.92, 1.00, and 2.28, respectively), although the direct effect of two levels of dosage was negative ( 0.28 and 0.31), and the mediation by parenting role identity in the dosage effect model was significant (B = 0.12, p < .05 for both low and high attendance groups; not shown). In sum, Hypothesis 3 received partial support. That is, the intervention, particularly high levels of attendance at TYRO, increased intervention group fathers’ perception of coparenting quality, parenting efficacy, and parenting role identity, which in turn contributed to an increase in those fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child and the frequency of father child activities over time. DISCUSSION The objective of the current study was to conduct a rigorous evaluation of an Ohio-based fatherhood program to determine whether the program achieves its intended goals. We found some evidence that the program is effective in making a positive difference in the lives of lowincome fathers. Before discussing the results of this study, it is necessary to acknowledge the limitations regarding high no-show rates for the baseline survey. As presented in Figure 1, we randomized 469 participants interested in participation, but 53% (217 of 469) of these participants did not show up for the baseline appointment. We believe there are two reasons for this. First, the study population was highly mobile. We sent out a reminder mail that might have been delivered to the wrong address. Or even if it was delivered correctly, they might have had other obligations during the baseline appointment. Future researchers who wish to study similar populations should make every effort to reduce no-show rates, for example, by sending email or text reminders as well as regular mail. Another potential reason for the high no-show rates was because the program completion came with an opportunity to work as a truck driver at a company. This means that being assigned to the control group would result in the loss of that opportunity because those assigned to the control group had to wait until the study was completed. It was very likely that some of those fathers might have dropped out of the study to enroll in a non–study-related TYRO class. We had no control over such dropout to decrease no-show rates. Because those 217 dropouts did not provide baseline data, there may be differences between those dropouts and the fathers who completed baseline assessment, and those differences may have introduced bias into the data. Therefore, the subsequent discussions of the findings should be considered in light of that limitation. One of the important findings of the current study is that TYRO improved fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child if they participated in the program regularly, attending most sessions—at least 80%. Our estimated growth curve models suggested that fathers enhanced their satisfaction with their relationship with their child not only during and immediately after the intervention but also 3 months after the intervention ended. Figure 3, which shows changes in the mean of all outcome variables across the three surveys, illustrates that, compared with the other two groups of fathers, fathers who attended eight or more sessions showed a pattern of increase in satisfaction with their relationship with their child over time. Second, as observed in Figure 3, TYRO helped fathers increase their perception of parenting efficacy over the 4-month period of study. This finding, which was robust to both intervention and dosage effects models, was encouraging because TYRO focuses their curriculum on self-confidence and positive self-image as fathers. For example, two of the lessons, “The Great I Ams” and “Family Crest” emphasize helping fathers develop a sense of empowerment, selfesteem, and a positive vision for their family future. As a recent qualitative study reported, many low-income fathers, who suffer from low self-esteem and instability of their father 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 288 289 Satisfaction with the Relationship with the Child 4.000 Frequency of Father–Child Activities 3.500 3.000 3.800 2.500 3.600 2.000 1.500 3.400 1.000 3.200 .500 .000 3.000 Time 1 Time 2 Time 1 Time 3 Parenting Efficacy Time 2 Time 3 Parenting Role Identity 3.600 3.800 3.500 3.700 3.400 3.600 3.300 3.500 3.200 3.400 3.100 3.000 3.300 Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Coparenting Relationship 3.100 3.000 2.900 2.800 2.700 Control group 2.600 Less than 8 sessions attended 2.500 Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 8 or more sessions attended F I G U R E 3 Group Means of Parenting Outcomes at the Time of Pretest (Time 1), Posttest (Time 2), and FollowUp Survey (Time 3) identity, appreciate the emotional support that they receive from instructors in the fatherhood program (Randles, 2020). Third, fathers’ perception of coparenting quality, along with parenting efficacy, turned out to be strongest change that TYRO brings about to the study participants. This result is important because other previous evaluation studies have not confirmed this finding (Avellar et al., 2018; Sarfo, 2018). We speculate that fathers may have made every effort to improve their relationship with their child’s mother for the sake of becoming a good father, as they were encouraged to do so while taking TYRO. Or possibly, the child’s mother may have observed genuine changes in the father’s character, behavior, and attitude over the study period. As a result, the child’s mother might have become more willing to “open the gate” and cooperate with the father, which could boost their perception of the coparenting relationship (Fagan & Cherson, 2015). Qualitative research may shed light on the process by which fathers perceive their relationship with the child’s mother positively by collecting data from the child’s mother. Fourth, we found evidence that TYRO improved fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child partly because it helped enhance their parenting role identity and perception of coparenting relationship with the child’s mother. The latter finding corroborates previous findings regarding the importance of parental alliance from evaluation research. For example, Rienks et al. (2011), who evaluated a 2-week relationship education program, found an increase in parental alliance to be related to an increase in father involvement at posttest. Because of the relatively short intervention, however, the authors could not address whether the positive effect of parental alliance would last months after the intervention ended. Our study showed the effect of coparenting lasted for 3 months after the intervention. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS FAMILY RELATIONS We also found that TYRO increased the frequency of father–child activities by enhancing the father’s perception of coparenting relationship with the child’s mother, but this positive indirect effect is at odds with the intervention’s negative direct effect on frequency of father–child activities. That is, controlling for the three hypothesized mediators, the intervention was found to decrease the frequency of father–child activities. Although this counterintuitive finding is difficult to explain without additional data, it might have been a methodological artifact due to limited measurement of father–child activities. For example, if we had asked fathers to list their activities with the child or to provide a diary instead of having them respond to our provided list of activities, the results might have been different. Regardless, to the extent that TYRO enhanced secondary outcomes of parenting, particularly the father’s coparenting relationship with the child’s mother, the intervention was found to help fathers increase the frequency of activities with their child. Finally, another noteworthy finding is that fathers who attended eight or more sessions reported an increase in parenting efficacy, which in turn led to improved fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child and, to a lesser extent, higher frequency of father–child activities. For example, a previous study found fathers’ enhanced parenting efficacy reduced barriers to parenting among low-income fathers in rural Midwestern communities, which in turn increased engagement with their children (Freeman et al., 2008). Our study found the same: Increased parenting efficacy among fathers enhanced the father–child relationship in terms of perceived satisfaction with the relationship with the child. This finding suggests that fatherhood programs should be designed to help fathers develop a sense of self-efficacy in parenting because the results of this study suggest that self-confidence has an important impact on the quality of father–child relationship. In addition, program staff should be mindful of the importance of being supportive of participating fathers and addressing their worries about failing to become a “good” father. For the same reason, fatherhood programs need to be designed to help fathers believe the importance of the father’s role in parenting a child, as we found an increase in the perception of role identity to be positively associated with an increase in fathers’ satisfaction with their relationship with their child and the frequency of father–child activities. Limitations Besides the limitations mentioned earlier, our study has other methodological limitations. Although the secondary outcomes were hypothesized to mediate the intervention effect on the primary outcomes, which was the program’s ultimate interest, the causal order between the outcomes could not be empirically established because they were both measured simultaneously. Readers should keep this in mind when interpreting the results. Another limitation is that our findings are based on fathers’ self-reports; thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that fathers’ reports of their perception of their relationship with their child and their child’s mother may not be congruent with how their child and the mother of their child actually feel about their involvement (Hernandez & Coley, 2007). Previous research has found discrepancy between fathers’ and mothers’ reports of father involvement (Fagan et al., 2007), where mothers report more accurately about father involvement (Dyer et al., 2014). In anticipation of this possibility, we planned to survey the mothers of their child, but due to budget constraints, we were unable to do so. Future research needs to examine father involvement from reports of multiple informants, including the mother of the child and the child. Implications for Practice One of the primary implications of the present study is that program dosage is important to the effectiveness of responsible fatherhood programs. Therefore, organizations implementing such 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 290 291 programs need to optimize fathers’ amount of participation in the program, evaluate program outcomes in relation to dosage, and identify the optimal levels of attendance for achieving desired outcomes. Accomplishing this goal would require analysis of not only quantitative but also of qualitative data such as feedback from program facilitators who have direct experience interacting with participating fathers. In the case of TYRO Dads, The RIDGE Project had implemented the program for more than a decade at the time of this study and had previously determined that participating fathers must attend at least eight of 10 sessions to be considered a program completer and to receive a TYRO pin, signifying the adoption of a new identity as a responsible father. Similarly, other fatherhood program providers—especially working for clients at non–halfway-house locations—may want to reach out to those fathers who find it difficult to make it to the workshop. Using aggressive reminder strategies, having face-to-face contact, and providing transportation and onsite childcare could help facilitate attendance. Encouraging class attendance and providing some type of recognition to participants who meet the data-based attendance threshold for program completion is essential for the success of the program. Another implication for practitioners is to offer employment benefits to study participants as they boost enrollment and completion rates in fatherhood classes. Despite modest financial incentives for their participation in three surveys ($20 for pre- and posttests and $50 for followup surveys), more than half of eligible fathers did not show up for the baseline assessment. According to the RIDGE Project staff, these fathers did not want to take the risk of being assigned to the control group. Indeed, they wanted to attend classes right away. Upon completion of eight out of the 10 TYRO classes, fathers were eligible to access WIOA funding for occupational training. This incentive played an important role in enrolling in TYRO. Although many enrolled fathers failed to receive a certificate that led to the WIOA benefit, enrolled fathers attended an average of five out of 10 sessions, which is higher than the dosage rate observed in many fatherhood programs. The possibility of receiving WIOA funding for employment training was a powerful incentive for fathers to participate in TYRO; other fatherhood program providers should consider providing similar incentives to their participants. Finally, fatherhood programs should implement a curriculum to teach how to develop coparenting skills as they play a significant role in facilitating father’s engagement with the child. Although observational research has consistently shown that fathers’ relationship quality with the child’s mother is critical in active involvement in their children’s lives (e.g., Carlson et al., 2008), it is only recently that coparenting relationship has been explored in experimental research (Pruett et al., 2017). Our study contributes to the literature by demonstrating that fathers in the intervention group improved their relationship with the child partly because their relationship with the child’s mother improved. Therefore, programs targeting low-income, nonresidential fathers should integrate coparenting classes and services into their programs for fathers. From a research point of view, it will be interesting to examine the impact of coparenting classes on fatherhood outcomes. At the same time, practitioners will also benefit from such research as they consider how the sequence of programs may affect the outcomes of their clients. R E FE RE NC E S Adams, B. L. (2018). Paternal incarceration and the family: Fifteen years in review. Sociology Compass, 12(3), e12567. Administration for Children and Families. (2015). FY 2015 healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood grantees. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/healthy-marriage-grantees Avellar, S., Covington, R., Moore, Q., Patnaik, A., & Wu, A. (2018). Parents and Children Together: Effects of four responsible fatherhood programs for low-income fathers (OPRE Report No. 2018-50). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Berger, L. M., & Carlson, M. J. (2020). Family policy and complex contemporary families: A decade in review and implications for the next decade of research and policy practice. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 478–507. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS FAMILY RELATIONS Bollen, K. A., & Curran, P. J. (2006). Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. John Wiley & Sons. Carlson, M. J., McLanahan, S. & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2008). Coparenting and nonresident fathers’ involvement with young children after a nonmarital birth. Demography, 45(2), 461–488. Carlson, M. J., Pilkauskas, N. V., McLanahan, S. S., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2011). Couples as partners and parents over children’s early years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(2), 317–334. Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. Cohen, R. S., & Weissman, S. H. (1984). The parenting alliance. In R. S. Cohen, B. J. Cohler & S. H. Weissman (Eds.), Parenthood: A psychodynamic perspective (pp. 33–49). Guilford Press. Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., & Wong, J. J. (2009). Promoting fathers’ engagement with children: Preventive interventions for low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(3), 663–679. Cox, M. J., Paley, B., & Harter, K. (2001). Interparental conflict and parent–child relationships. In J. H. Grinch & F. D. Fincham (Eds.), Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research and applications (pp. 249– 272). Cambridge University Press. Dyer, W. J., Day, R. D., & Harper, J. M. (2014). Father involvement: Identifying and predicting family members’ shared and unique perceptions. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(4), 516–528. Dyer, W. J., Kauffman, R., Fagan, J., Pearson, J., & Cabrera, N. (2018). Measures of father engagement for nonresident fathers. Family Relations, 67(3), 381–398. Edin, K., & Nelson, T. J. (2013). Doing the best I can: Fatherhood in the inner city. University of California Press. Fagan, J., Bernd, E., & Whiteman, V. (2007). Adolescent fathers’ parenting stress, social support, and involvement with infants. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(1), 1–22. Fagan, J., & Cherson, M. (2015). Maternal gatekeeping: The associations among facilitation, encouragement, and lowincome fathers’ engagement with young children. Journal of Family Issues, 38(5), 633–653. Fagan, J., & Palkovitz, R. (2011). Coparenting and relationship quality effects on father engagement: Variations by residence, romance. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(3), 637–653. Fagan, J., & Pearson, J. (2020). Fathers’ dosage in community-based programs for low-income fathers. Family Process, 59(1), 81–93. Freeman, H., Newland, L. A., & Coyl, D. D. (2008). Father beliefs as a mediator between contextual barriers and father involvement. Early Child Development and Care, 178(7–8), 803–819. Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (2009). Methods and measures: The network of relationships inventory: Behavioral systems version. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(5), 470–478. Guzzo, K. B. (2014). New partners, more kids: Multiple-partner fertility in the United States. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 66–86. Hayward, A., McCue. R., Hou, W., McKillop, A., & Lee, S. J. (2019). A randomized controlled trial to examine the impact of cell phone technology on engagement and retention of fathers in a fatherhood program. https://www.frpn. org/asset/frpn-grantee-report-randomized-controlled-trial-examine-the-impact-cell-phone-technology Hernandez, D. C., & Coley, R. L. (2007). Measuring father involvement within low-income families: Who is a reliable and valid reporter? Parenting: Science and Practice, 7(1), 69–97. Holmes, E. K., Egginton, B. M., Hawkins, A. J., Robbins, N. L., & Shafer, K. (2020). Do responsible fatherhood programs work? A comprehensive meta-analytic study. Family Relations, 69(5), 967–982. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. LaRossa, R. (1988). Fatherhood and social change. Family Relations, 37(4), 451–457. McLanahan, S., Tach, L., & Schneider, D. (2013). The causal effects of father absence. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 399–427. Muthén, B. O. (1983). Latent variable structural equation modeling with categorical data. Journal of Econometrics, 22(1983), 43–65. Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. Osborne, C., Austin, J., Dion, M. R., Dyer, J., Fagan, J., Harris, K. E., Hayes, M., Mellgren, L., Pearson, J., & Scott, M. E. (2014). Framing the future of responsible fatherhood evaluation research for the fatherhood research and practice network. Fatherhood Research & Practice Network. Pasley, K., Petren, R. E., & Fish, J. N. (2014). Use of identity theory to inform fathering scholarship. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6(4), 298–318. Paquette, D. (2004). Theorizing the father–child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development, 47(4), 193–219. Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2017). Enhancing father involvement in low-income families: A couples group approach to preventive intervention. Child Development, 88(2), 398–407. Randles, J. (2020). The means to and meaning of “being there” in responsible fatherhood programming with lowincome fathers. Family Relations, 69, 7–20. Rane, T. R., & McBride, B. A. (2000). Identity theory as a guide to understanding fathers’ involvement with their children. Journal of Family Issues, 21(1), 347–366. 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 292 293 Rienks, S. L., Wadsworth, M. E., Markman, H. J., Einhorn, L., & Etter, E. M. (2011). Father involvement in urban low-income fathers: Baseline associations and changes resulting from preventive intervention. Family Relations, 60(2), 191–204. Sarfo, B. (2018). The DAD MAP evaluation: A randomized controlled trial of a culturally tailored parenting and responsible fatherhood program. https://www.frpn.org/asset/frpn-grantee-report-the-dad-map-evaluation-randomizedcontrolled-trial-culturally-tailored Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., & Fagan, J. (2020). The evolution of fathering research in the 21st century: Persistent challenges, new directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 175–197. Stevenson, M. M., Fabricius, W. V., Cookston, J. T., Parke, R. D., Coltrane, S., Braver, S. L., & Saenz, D. S. (2014). Marital problems, maternal gatekeeping attitudes, and father–child relationships in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 50(4), 1208–1218. Stryker, S., & Serpe, R. T. (1994). Identity salience and psychological centrality: Equivalent, overlapping, or complementary concepts? Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(1), 16–35. The RIDGE Project. (n.d.). TYRO declaration. Retrieved from https://theridgeproject.com/tyro-pledge/ Western, B., & Smith, N. (2018). Formerly incarcerated parents and their children. Demography, 55(3), 823–847. SU P PO RT I NG I NF O RM AT IO N Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website. How to cite this article: Kim, Y.-I., & Jang, S. J. (2023). A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of the TYRO Dads Program. Family Relations, 72(1), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12641 17413729, 2023, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fare.12641 by Open University Of Israel, Wiley Online Library on [19/07/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License TYRO DADS