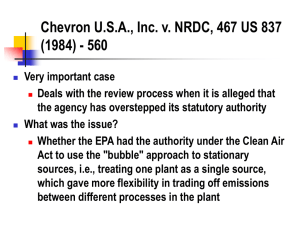

Administrative Law: Agency Definition & Rulemaking vs. Adjudication

advertisement