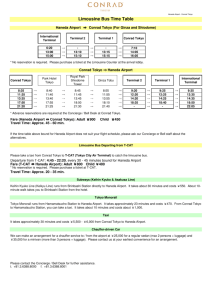

SENECA COLLEGE TOKYO INTL. HANEDA Historical Analysis John Campbell 11/10/2016 Professor Wafaei Introduction Tokyo’s airport system has expanded rapidly since the 1960s caused by deregulation and the expanding middle class in Japan. This has impacted the aviation market significantly and large investments have been made to support the growing traffic. This paper will analyze the growth of Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport since its founding and how it has adapted to rapid changes in the Japanese economy and deregulation. Background Information Tokyo International Airport (Haneda), also known as Haneda Airport (HND), was founded in 1931 on a small piece of land located at the south end of the airport’s modern position. It was the main operating base of Japan’s former flag carrier, Japan Air Transport, and handled daily domestic and international flights to Japan, Korea, and Manchuria (North East China). Following World War II, Haneda was occupied by the US Army for several years and operated as a regional base for the United States Navy during the Korean War. Haneda was handed back to the Japanese government in 1958 which allowed the airport to begin large expansions to accommodate the jet age. After some terminal and runway expansions in the 1960s, the Japanese government commenced work to open a second airport (Narita) for international flights. After Narita airport began operations in 1978, Haneda entered its “Domestic era”. Throughout this phase, pressure to expand for international traffic subsided, however, Haneda officials foresaw extra domestic traffic from deregulation which motivated the construction of a three new 9,800ft runways in 1988, 1998 2 and 2000, and the construction of a new terminal building “Big Bird” in 1993. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of these expansions. Figure 1: Tokyo International Airport (Haneda) expansion timeline (1971-2007). (Watabe, 2012) Domestic airline traffic in Japan has gone through a long history of growth and maturity since its beginnings in the 1960s. Three airlines were founded then, and after the government liberalized route entry and frequency regulations in 1985, multiple others began entering the market. (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) The Japanese government continued to deregulate the aviation industry by introducing a zone airfare system in 1995 which aimed to accelerate reduced airfares and foster the diversification of discount airlines. This fuelled the introduction of two new airlines in 1998. The final step of deregulation in 2000 eliminated supply and demand regulations and prior approval of airfares. Once these final deregulatory laws were passed, the market was considered “fully competitive” and resulted in more rapid increases in annual market demand. 3 (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) Emphasis was placed on airport expansion during these times as their capacity (supply) was lagging behind market demand. Tokyo International Airport (Haneda) had special priority as it was and still is today, the busiest and most valuable hub airport in Japanese territory. In 2015, Haneda International Airport processed 75,254,942 passengers. (Statista, 2015) In perspective, Japan’s second busiest airport in 2015 was Tokyo International Airport (Narita) which processed 34,751,221 passengers (less than half of Haneda). Haneda airport has experienced consistent growth since its founding in the 1960s and recently, annual passenger traffic progressions of 2-3% growth are normal (Figure 1). However, in 2010 a new international Figure 2: Tokyo International Airport (Haneda) passenger growth 2000-2015. (Statista, 2015) terminal was opened and has since accelerated growth as Haneda attempts to break into the market. Figure 1 demonstrates that Haneda has grown from 62.58 million passengers 2011 to 75.32 million 4 in 2015 which indicates 4% growth on average. Prior to the introduction of the international terminal, growth was much shallower (2-3%). Since 1978, Haneda’s sister airport, Narita, dominated the international market because the government strictly separated domestic and international traffic in 1978 illustrated in Figure 2. due to the jet age causing a rapid increase in Figure 3: Domestic and international traffic data; Narita vs. Haneda. (Japan Airport Terminal Co., Ltd, 2016) demand, and Haneda’s inability to manage the extra traffic. Haneda’s domestic era ended in June 2007 when the government began allowing international arrivals during Narita’s closed hours. This caused international demand to slowly increase and prompted the construction of a dedicated international terminal and fourth runway (Figure 4) which was opened in 2010. This construction project alone increased Haneda’s operational capacity from 285,000 aircraft movements to 407,000. Since then, Haneda has begun 5 to slowly steal the international market from Narita because of its preferable geographic location relative to downtown Tokyo. Haneda’s location is 60 km closer to downtown than Narita which Figure 4: Site construction of Haneda's international terminal and fourth runway. (Watabe, 2012) is attractive to business travellers and those visiting for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo. Currently, future expansions are being planned to account for the extra slots required to accommodate the 2020 Tokyo Olympic games. This includes a new railway line to Tokyo’s downtown train station, and large terminal expansions. In a document prepared by Japan’s Airport Terminal Co., they outlined a vision for Haneda to be the top airport in the world by 2020 in preparation for the Olympic Games: 6 “Positioned as we are in the airline industry, and with the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games coming up, airport facilities in the Tokyo metropolitan region are being enhanced, a new annual target of 40 million foreign visitors has been set for the year 2020, and the demand for airport facilities and services is expected to continue rising.” (Japan Airport Terminal Co., Ltd, 2016) In order to accommodate the increase in demand, the Tokyo Airport Terminal Co. has created a three level strategy plan to execute their goal of becoming the top airport in the world. They include; “expand business domains that leverage strengths and diversify earnings”, “pursue ‘vision’ for Haneda airport”, and “redevelop earnings base and establish competitive position”. The vision provided for Haneda’s 2016-2020 outlook is illustrated in Figure 5. It is clear that Figure 5: Tokyo International Airport (Haneda) 2016-2020 vision. (Watabe, 2012) Haneda airport officials have adopted a business value model and will focus on branding the airport as a global ‘benchmark’ over the next four years. To execute Haneda’s vision, the investment plan is allocating $1 billion spread across 4 years. Within this investment, $500 million (USD) will be used for “security level enhancement, universal design for Tokyo Olympics”, $350 million to “the expansion of business domains that leverage strengths and earnings diversification”, $100 million for “redevelop[ing] earnings base and establish[ing] competitive position”, and $50 million for the “realignment and enhancement of organization, human capital and governance.” (Japan Airport 7 Terminal Co., Ltd, 2016) With all expenses considered over the next four years, Haneda’s 2018 projections include an operating revenue of $2.38 billion and a consolidated operating profit of $140 million which maintains their profit ratio goals of 5 percent. Deregulation in the Airline Market Airport capacity expansion in Japan paralleled regulatory reform by the government in order to accommodate the increasing demand. In general, airport construction and expansion with respect to deregulation was completed at the end of the 20 th century because no significant reform laws have been passed since then. Growth today is mainly due to the effect of globalization, increasing regional population, and the tourism industry. In order to analyze how deregulation effected Tokyo’s Haneda airport, a historical perspective must be used for the period between 1960 to 2000. In this period, the government implemented two major regulatory reforms. They include; the promotion of double/triple tracking of domestic aviation, and the regulatory reform of domestic airfares. (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) Double/Triple Tracking: In the 1980s the airline industry was undergoing rapid change to adapt to the ever growing demand in the aviation industry. The government recognized the instability of the aviation market and decided to regulate the number of airlines capable of operating on one route based on annual passengers. This became known as “double/triple tracking”. This framework was laid out in 1985 by Japan’s Ministry of Transport whereby “double tracking” and “triple 8 tracking” were routes operated by two or three airlines respectively. The Ministry of Transport was then responsible for setting the number of annual passengers required to allow double or triple tracking. Originally, 700 thousand passengers were required for double tracking, and one million for triple tracking. This regulatory policy was introduced mainly to foster balanced development in the aviation market, however, over time it became evident that the double/triple tracking constraints were limiting growth and competition. Thus, in 1997 the policy was removed allowing any number of airlines to fly a route regardless of passenger volume. The result was an increase in total available seats from 53% to 80% for the period between 1985 and 1999. (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) Regulatory Reform of Domestic Airfare: The regulation of domestic airfares was introduced to limit the increase of airfares that did not have proper reasoning for the increase. Thus, airlines were required to apply for airfare increases during times of higher than normal inflation or increased fuel costs. The Civil Aviation Bureau was responsible for this policy, and only allowed airfare increases up to a level which balanced “income to aggregate cost under efficient operation”. (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) Before long, this was deemed market demand limiting and in 1996, a “zone airfare” system was adopted which allowed airlines to set airfares up to 25% under the standard cost of routings. This system allowed airlines to promote flexible airfares, seasonal fare sales, and flight-to-flight pricing schemes, which has ultimately expanded the airline market in Japan. 9 Economic Impact of Deregulation It has been examined in multiple economic studies that the deregulatory policies enacted between 1980-2000 have had a positive effect on the Japanese airline industry. Through use of econometric analysis, the demand relative to the introduction of deregulation was calculable and has been illustrated in graphs. A secondary result has been an overall reduction in airfare prices. In a study conducted by the Japanese Civil Aviation Bureau, they concluded the reason for the economic improvements are due to: - Improvement of the income level per capita due to macroeconomic growth - Travel cost drop due to market economies of scale caused by deregulation (MLIT, 1998) This economic growth is demonstrated in Figure 6 which illustrates the change in demand based on thousand passenger km between 1985-2000. Figure 6: Japan's passenger demand and average airfare curve. (MLIT, 2002) 10 The effect of the deregulatory policies at Haneda airport was difficult to analyze directly as there are many variables that must be included. In a Japanese government analysis, they studied the economic growth based on “user-benefit” by attempting to separate each policy and compare it to the number of expansion slots at Haneda. User-benefit was defined as the economic growth due to a certain policy or expansion enacted. What was found is each policy had its own level of effect on the economy and number of slots at Haneda. They concluded that the deregulatory policies were tied closely to the expansion of the airport. The data generated is Table 1: User benefit of Japanese degregulation at Haneda airport (billion yen/year). (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) shown in Table 1. It can be observed in the data that slot growth at Haneda grew equally with the demand generated by each policy introduced. It is especially clear when the introduction of zone flexible fares occurred in 1995 where the extra 100 billion yen ($1 billion US) in demand, caused a 50 billion yen ($5 billion US) increase at Haneda the following year. Overall, the study confirmed that the user-benefit of deregulation between 1985 to 1999 was 440 billion yen ($4.4 billion US) per year on average. Of the yearly average user-benefit, it was suggested that 30% of 11 the it was due to Japan’s economic market growth, and 60% was a direct result of deregulation. (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) A graphical representation of this data is on Figure 7. Figure 7: Graphical representation of user benefit caused by deregulation in Japan. ( (Yamaguchi, et al., 2007) Conclusion Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport has been undergoing significant develop over the last eighty years. Multiple terminal expansions, runway additions and extensions, public transport upgrades, and policy changes, have molded the airport into its modern form today. Over the last 40 years, Haneda airport has been naturally responsive to deregulatory policies and has also been directly competing with its neighbour airport Narita. Historically, Narita has dealt with solely international traffic, however, since the international terminal expansion and runway 12 addition in 2010, it has slowly begun stealing the international market as it becomes the focal airport in preparation for the 2020 Olympics. Haneda’s plan to prepare for the future increases in demand was described to be both financially and globally aggressive as they take aim to be the top airport in the world. 13 Works Cited Japan Airport Terminal Co., Ltd. (2016). Medium-Term Business Plan. To Be a World Best Airport. Tokyo, Kanto, Japan. MLIT. (1998). Developing New Transportation Policies . Tokyo, Kanto, Japan. Watabe, T. (2012). Development History of the Tokyo International Airport. Tokyo, Japan. Yamaguchi, K., Ohashi, T., Ueda, T., Takuma, F., Hidaka, T., & Tsuchiya, K. (2007). Economic Impact Anlysis of Deregulation and Airport Expansion in Japanese Domestic Aviation Market. Tokyo, Chiyodaku, Japan. 14