Relational Leadership & Employee Creativity in Hospitality

advertisement

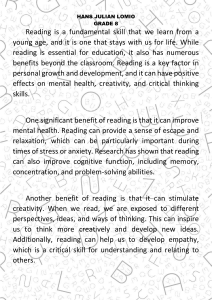

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363946602 Relational leadership and employee creativity: the role of knowledge-sharing behaviour and leader–follower dyadic tenure Article in Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights · September 2022 DOI: 10.1108/JHTI-06-2022-0218 CITATION READS 1 39 3 authors, including: Abraham Ansong Ethel Esi Ennin University of Cape Coast University of Cape Coast 46 PUBLICATIONS 550 CITATIONS 1 PUBLICATION 1 CITATION SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Call for Book Chapter-Corporate Governance models and Application in Developing Countries View project All content following this page was uploaded by Ethel Esi Ennin on 23 February 2023. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2514-9792.htm Relational leadership and employee creativity: the role of knowledge-sharing behaviour and leader–follower dyadic tenure Abraham Ansong Department of Management, School of Business, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana Ethel Esi Ennin Relational leadership and employee creativity Received 3 June 2022 Revised 3 July 2022 10 August 2022 13 September 2022 Accepted 14 September 2022 Centre for Continuing Education, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana, and Moses Ahomka Yeboah Department of Entrepreneurship and Agric-Business, Cape Coast Technical University, Cape Coast, Ghana Abstract Purpose – The study investigated the effects of relational leadership on hotel employees’ creativity, using knowledge-sharing behaviour and leader–follower dyadic tenure as intervening variables. Design/methodology/approach – A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from 355 employees of authorized hotels from the conurbation of Cape Coast and Elmina in Ghana. To evaluate the study’s research hypotheses, the authors used WarpPLS and PLS-SEM. Findings – The findings demonstrated that while knowledge-sharing behaviour did not directly affect employee creativity, it did have a significant mediating effect on the link between relational leadership and the creativity of employees. The study also revealed that the ability of relational leaders to drive knowledgesharing behaviour was not contingent on leader–follower dyadic tenure. Practical implications – The results of this study have practical relevance for human resource practitioners in the hospitality industry. Given that relational leadership has a positive relationship with employee creativity, the authors recommend that hotel supervisors relate well with employees by sharing valuable information and respecting their opinions in decision-making. Originality/value – Studies on the role of relational leadership and employee creativity are scanty. This study develops a model to explain how relational leadership could influence employee creativity by incorporating knowledge-sharing behaviour and leader–follower dyadic tenure. Keywords Relational leadership, Employee creativity, Knowledge-sharing behaviour, Leader–follower dyadic tenure, Hotels, Ghana Paper type Research paper Introduction The hospitality industry consists of clients that are increasingly searching for better services that meet and/or exceed their expectations (Ampong et al., 2021; Bani-Melhem et al., 2018; Vakira et al., 2022). Hence, the industry seeks a workforce that has a strong capacity for creativity to help meet these ever-increasing demands (Javed et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019; Nasifoglu Elidemir et al., 2020). Researchers in hotel management have highlighted the need for employees to be creative so as to effectively carry out both regular job demands and other specialized customer service (Lan et al., 2022). At the organizational level, it has been found that employee creativity has a strong impact on an organization’s competitive advantage and growth (Khalid and Zubair, 2014; Zhou and Hoever, 2014). Employee creativity also fuels organizational innovation (Tu et al., 2019; Zhou and Hoever, 2014) which can heighten an organization’s ability to adapt and remain relevant (Gerstein and Friedman, 2017; Zhou and Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights © Emerald Publishing Limited 2514-9792 DOI 10.1108/JHTI-06-2022-0218 JHTI Hoever, 2014). At the individual level, creative employees are known to be more comfortable embracing the unknown (Hensley, 2020). They have also demonstrated higher levels of resilience when seeking ways of handling uncertainty (Venckut_e et al., 2020). Employee creativity is an intellectual process of generating fresh and practically useful ideas (Zhou et al., 2022). Creative ideas are the foundation of all innovation, as Amabile and Pratt (2016) pointed out. A person or team needs to have a strong concept and the ability to develop it beyond its initial state in order to successfully implement new initiatives, new product debuts or new services. The hotel industry needs the creativity of its frontline employees, who are usually in close contact with guests and thus tend to know their needs and wants, to develop new products and services. Th suggestions of frontline workers assist change in current work procedures in areas such as administration, information flow, service range and back-office innovation (Danvour et al., 2021). Their recommendations help to modernize present working practices in administration, information flows, service scope and back-office innovation, among other areas. Some scholars claim that frontline workers often have a greater understanding of the need for workplace improvements than top management (Carmeli and Spreitzer, 2009). Zona and Adrian (2020) advanced that factors such as self-encouragement and encouragement from the environment promote the realization of individual creativity. Leaders are instrumental at creating a workplace environment that fosters employee creativity. Although leadership styles, in the hotel sector, have been recognized as significant influencers of employee creativity (Bhutto et al., 2021; Hassi, 2019; Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2021), there is a paucity of evidence on how relational leadership style affects employee creativity. Also, Elkhwesky et al. (2022) bemoaned the neglect of relevant intervening variables by researchers in investigating the nexus between leadership styles and employee behaviour following their critical review of empirical studies on leadership styles in contemporary hospitality. According to Breevaart and de Vries (2021), relational leadership focuses on the overall welfare of followers by connecting with them, listening to their input, demonstrating trust and confidence in them and praising their accomplishments. Unlike other forms of leadership styles, relational leaders provide encouragement to employees in risky and challenging tasks, recognize their efforts and ensure the availability of resources necessary to engender creativity (De Jong and Den Hartog, 2007). Kim et al. (2021) posited that although a leader’s knowledge-sharing behaviour plays a critical role in promoting employee creativity, it has not received the required attention from scholars. Hence, this study seeks to answer two main questions, including (1) does relational leadership positively influence employee creativity? and (2) If yes, do knowledge-sharing behaviour and leader–follower dyadic tenure play any intervening role in the hospitality and tourism industry of Ghana? Ghana is proud of its heritage tourist industry, which is largely a result of the 400-year-old transatlantic slave trade (Boateng et al., 2018; Dillette, 2021; Yankholmes and McKercher, 2015). More so, it is a destination for business travellers, backpackers and volunteer tourism alike (Adu-Ampong, 2018; Bargeman et al., 2018; Dayour et al., 2016; Mensah et al., 2017; Yankholmes, 2018). The 2020 Tourism Report by the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture reported on some of the most visited places in Ghana. This includes the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park, Manhyia Palace, Kintampo Waterfalls, Komfo Anokye Sword, Lake Bosomtwi, Mole National Park, Kumasi Zoo, Shai Hills Reserve, Nzulezo, Boabeng-Fiema Monkey Sanctuary and Zenga Crocodile Pond. Furthermore, the report also ranked Kakum National Park to be 1st among the top ten most visited attractions/sites in Ghana from 2016 to 2020. This is followed by the Cape Coast Castle as the 2nd, and Elmina Castle is ranked 5th. These three tourist sites are located in Cape Coast and Elmina. The study adds to the body of knowledge and current practice in the hospitality and tourist sectors. First, it combines research in the hospitality sector on relational leadership and knowledge management. Second, using knowledge-sharing behaviour and leader–follower dyadic tenure as intervening variables, it studies relational leadership and employee innovation in the hospitality sector. Finally, the study offers practical recommendations for hoteliers that embrace relational leadership and thus stimulate a discussion on how hoteliers and managers can work better with employees to achieve desired organizational outcomes in the context of social exchange theory. Literature review Theoretical review The social exchange theory, proposed by Blau (1964), advanced that social exchanges necessitate undefined obligations. When a person demonstrates kindness towards another person, he/she feels pretty sure that he/she will get a response in an undefined time, place and style in the future (Wayne et al., 1997). The basic idea behind the principle of reciprocity is that obligations of repayment are based on the value attributed to the benefit received (Gouldner, 1960). Alternatively said, the degree to which one feels obligated to return will depend on how valuable the exchange with the other party is seen to be. There is a suggestion that some elements, including the degree of the recipient’s exigency and the parties’ status during the period of the exchange, may have an impact on the exchange’s worth and the subsequent sense of obligation (Gouldner, 1960). Thus, we reasoned that leaders who build positive relationships with employees, through knowledge-sharing behaviour, will engender greater felt obligation on the part of employees to be creative because knowledge is a cherished resource employees use in building their competencies at work (Liu et al., 2010). Leaders’ knowledge-sharing behaviour has been acknowledged as being among some of the important determinants of hotel efficiency and improvement given the influence it has on employee creativity (Al Hawamdeh, 2022). Consequently, using the principles of social exchange theory, this study investigates the association among relational leadership, knowledgesharing behaviour, leader–follower tenure and employee creativity. Hypotheses development Relational leadership and employee creativity Relational leadership improves employee creativity because it embraces inclusiveness (Amabile and Pratt, 2016; Baafi et al., 2021; Javed et al., 2017). From the viewpoint of social exchange theory, leaders that promote inclusiveness have a tendency to enhance employee creativity by being accessible and available to assist employees. Actions such as creating opportunities for professional and personal growth and encouraging risk-taking behaviour among employees are known attributes of relational leaders (Hollander, 2012). They also promote employees’ creativeness by making organizational resources available to their subordinates (Hollander, 2012). In addition, the emotional bonds that develop between relational leaders and their employees promote creativity since employees feel pressured to assist their leaders to become successful by creatively solving organizational challenges efficiently (Blau, 1964; Northouse, 2019). However, Ferch and Mitchell (2001) indicate the need to encourage intentional forgiveness in organizations that practice relational leadership style to ensure its effectiveness. The authors argue that this is necessary due to the likely manifestations of personality clashes, ideological differences and dysfunctional communication between the leader and his followers. These downsides to relational leadership could lead to low employee creativity and productivity. Empirical evidence, based on studies employing attributes of relational leadership, suggests relational leadership could have positive impact on employee creativity. For instance, Hassi (2019) found that empowering leadership improves climate for creativity which then positively affects management innovation among employees of 127 hotels in Morocco. Again, Bhutto et al. (2021) analysed data from 302 workers in the tourist and hospitality industry and found that there is a link between green inclusive leadership and green creativity. Hence, we propose that: Relational leadership and employee creativity JHTI H1. Relational leadership has a significant positive relationship with employee creativity. Relational leadership and knowledge-sharing behaviour Relational leadership that empowers employees has been viewed as a crucial prerequisite for promoting knowledge-sharing behaviour (Bavik et al., 2018; Jada et al., 2019). Relational leadership fosters knowledge-sharing due to its tendency to empower employees (Jada et al., 2019). Relational leaders are known to be supportive and this includes allowing for autonomous thought among staff and providing constructive criticism (Amundsen and Martinsen, 2014). Specifically, such leaders encourage subordinates by sharing information through business official documents, the media, telling stories about organizational successes and failures as well as discussing their personal work experiences with subordinates. Using the social exchange theory as a foundation, it is reasonable to posit that relational leaders create a favourable climate for active learning, thereby stimulating personal initiatives (Kim and Beehr, 2018). Also, relational leaders in their quest to treat their followers well are more likely to adhere to moral principles, which could evoke favourable emotions and ease mental tension, resulting in the feeling of positive commitment and knowledge-sharing among workers (Lindebaum et al., 2017). By promoting high-quality workplace relationships, relational leaders establish a friendly communication atmosphere that encourages knowledge-sharing (Bonner et al., 2016). Thus, we anticipate that relational leaders are more likely to encourage knowledge-sharing behaviour in an organization. Hence, we predict that: H2. Relational leadership has a significant positive relationship with knowledge-sharing behaviour. Knowledge-sharing behaviour and employee creativity Knowledge-sharing is described as the process through which individuals exchange information and work together to develop new ideas (Lan et al., 2022). In the context of a hotel, knowledge refers to information necessary for rendering excellent customer service by complying with specified operational procedures (Yang and Wan, 2004). Knowledge is a resource that can be employed by organizations to improve the capabilities and skills of their employees (Liu et al., 2010). Liao et al. (2018) advanced that whenever knowledge is donated and received, employees gain novel ideas about crafting their jobs in a more meaningful way. Also, knowledge-sharing behaviour stimulates creativity because employees receive valuable insights from their supervisors, which boosts confidence and enhances their creative performance in the workplace. The positive impact of knowledge-sharing on employee creativity has been demonstrated in a number of earlier research (Akhavan et al., 2015; Kim and Lee, 2013; Nieves and Diaz-Meneses, 2018; Nham et al., 2020; Phung et al., 2017). Thuan (2020) used a paper-based survey among information technology businesses in Southern Vietnam to examine the effects of supervisor knowledge-sharing behaviour on subordinate innovation. Because employees profited from their supervisors’ expertise, information, experience and ideas, the study demonstrated that knowledge-sharing behaviours had a beneficial impact on employee creativity. In Vietnam, Phung et al. (2017) investigated the relationship between knowledge-sharing and creative work practices. According to the findings, the organization was able to encourage employee creativity because of the supervisors and employees’ willingness to share their knowledge. Again, the association between knowledge-sharing activities and innovation capability was examined by Nham et al. (2020). The results demonstrated that knowledge-sharing activities were crucial for enhancing personal creativity. Finally, with the help of 257 employees from 22 high-tech businesses in Iran, Akhavan et al. (2015) conducted study on the knowledge-sharing determinants, behaviours and innovative work behaviours and came to the conclusion that these behaviours increased employee creativity. Therefore, this study anticipates that: H3. Knowledge-sharing behaviour has a significant positive relationship with employee creativity. Mediating role of knowledge-sharing behaviour on the nexus between relational leadership and employee creativity Although empirical literature in the hospitality industry has demonstrated that relational dimensions of leadership stimulate employee creativity (Bhutto et al., 2021; Hassi, 2019), the role of knowledge-sharing behaviour in the association between relational leadership and employee creativity has not been given much attention. Leaders are important agents for employee creativity because they are responsible for effective knowledge management (Mota Veiga et al., 2022; Shukla et al., 2022). Relational leaders could possess better knowledge management capabilities and as such they could spur innovative behaviours among employees leading to the provision of newer and better services to clients. Based on the reciprocity argument supported by the central tenets of social exchange theory and our earlier justifications as well as the research evidence for hypotheses 2 and 3, it is reasonable to assume that relational leadership can affect knowledge-sharing behaviour, which may then favourably affect employee creativity (Blau, 1964; Gouldner, 1960; Wayne et al., 1997). We propose that the knowledge-sharing behaviour plays a major intermediary role in transmitting the effects of relational leadership on employee creativity. Hence, we hypothesize that: H4. The positive link between relational leadership and employee creativity is mediated by knowledge-sharing behaviour. Moderating role of leader–follower dyadic tenure on the nexus between relational leadership and knowledge-sharing behaviour Although there are conceptual and empirical reasons to expect that relational leaders could facilitate knowledge-sharing behaviour, relational leadership, by nature, provides employees with a lot of flexibility. Nevertheless, leader–follower dyadic tenure can actively encourage knowledge-sharing behaviour by increasing the frequency at which leaders and followers interact. Such interactions provide opportunities for employees to learn from managers and also offer suggestions to enhance the operational efficiency of organizations. Several studies have opined that an employee’s time spent with a leader might be an important determinant of the amount and quality of information the leader may be willing to share due to trust (Gnankob et al., 2022; Lewicki and Bunker, 1996). Over time, trust develops, mostly as a result of the parties’ history of productive interactions. (Jian and Dalisay, 2017). As a result, we anticipate that leader–follower tenure and relational leadership will interact to affect knowledge-sharing behaviour. Hence, we propose that: H5. Leader-follower dyadic tenure strengthens the association between relational leadership and knowledge-sharing behaviour. Conceptual framework This study developed an integrated framework to illustrate the hypothesized relationships (see Figure 1): Relational leadership has direct relationships with employee creativity (H1) and knowledge-sharing behaviour (H2), respectively; knowledge-sharing behaviour has a direct relationship with employee creativity (H3); and also mediates the relationship between relational leadership and employee creativity (H4), respectively. Finally, leader–follower dyadic tenure moderates the connection between relational leadership and knowledgesharing behaviour (H5). Relational leadership and employee creativity JHTI Leaders-follower Hotel grade dyadic tenure H4 Knowledge-sharing Relational leadership behaviour 4 Employee H3 creativity H2 H1 Self-efficacy Figure 1. Conceptual model Source(s): Researchers’ construction Research methods Sample size, sampling procedure and data collection procedure This study was based on a positivist paradigm. It used a cross-sectional survey design to gather data from the respondents. Quantitative approaches to research make it possible for the social environment, like the present study, to be represented as variables with numerical values so that their relationships can be statistically analysed (Creswell, 2014). The study was conducted among 62 licenced hotels within the Cape Coast-Elmina conurbation, Ghana. Geographically, Cape Coast and Elmina were chosen because they are geographically adjacent in terms of settlement and development. Also, they hold and receive the greatest number of attractions and tourist arrivals due to their diversity of attractions, which include historical, ecological and cultural attractions (Dayour, 2014). The Ghana Tourism Authority (GTA) categorizes hotels as 1-Star, 2-Star, 3-Star, Budget and Guest House. The nonmanagerial/non-supervisory staff population was also identified as, 102 office staff, 133 kitchen, restaurant and bar staff, 22 sales, marketing and accounts staff, 157 housekeeping staff and 151 engineering, security and support staff. From a heterogeneous population of 565 non-managerial/non-supervisory staff, 400 were randomly sampled, using a stratified sampling technique. The modified formula by Adam (2020) states that 316 is the minimal sample size needed for a population of 565. A 27% upward adjustment was made to this minimal sample size to account for potential non-responses. 355 out of the 400 respondents answered (i.e., 88.75% response rate) the questionnaire, which meets the minimum required sample size. Data were gathered based on a survey carried out from 1st December 2021 to 31st January 2022. Table 1 indicates the complete demographic information of the respondents. Instrument development Multiple indicators were used to measure the primary variables (relational leadership, knowledge-sharing behaviour, employee creativity and self-efficacy) in our research model. Socio-demographic characteristics Gender Age Missing Highest level of education Missing Marital status Hotel-grade Department Male Female Less than 20 21–30 31–40 41–50 51–60 Total System Primary JHS SHS Vocational/technical Tertiary Middle school Total System Single Married Divorced Widow/widower 3-star 2-star 1-star Budget Guest house Front Office Kitchen/Restaurant/Bar Engineering/Security/Support Sales/Marketing/Account Housekeeping Frequency (n 5 355) Percent (%) 193 162 10 171 143 28 2 354 1 10 26 136 99 79 3 353 2 217 128 7 3 89 96 84 70 16 74 102 80 22 77 54.4 45.6 2.8 48.2 40.3 7.9 0.6 99.7 0.3 2.8 7.3 38.3 27.9 22.3 0.8 99.4 0.6 61.1 36.1 2.0 0.8 25.1 27.0 23.7 19.7 4.5 20.8 28.7 22.5 6.2 21.7 To improve content validity, every indicator variable employed in the current study was sourced from existing literature (Straub et al., 2004). The final questionnaire was given to experienced professionals in the hospitality industry and some experts in the study area to cross-check for consistency, relevance, clarity and ambiguity. This was done in order to determine the validity of the instrument based on the research objectives. The items were then reworded to reflect the context of the study. To make the questionnaire understandable and user-friendly, their suggestions were integrated. Measurement instrument Twenty-five questions from the RLQ scale created by Carifio (2010) were utilized to estimate relational leadership. This scale had five sub-scales, namely; inclusiveness, empowering, caring, ethical and vision. Each of the dimensions of RLQ consisted of 5 items. The questions put forth by Lee (2001) about knowledge-sharing behaviours were modified to meet the survey items based on the views of Van Den Hooff and De Ridder (2004) and De Vries et al. (2006). The total number of items in this scale was 14. The eight items utilised to calculate employee creativity were also derived from Bass and Avolio (1995). Likewise, the New General Self-Efficacy (NGSE) Scale with eight items derived from Chen et al. (2001) was adapted to measure self-efficacy. They were calculated with a seven-point Likert scale where 1 represents the least level of agreement and 7 represents the highest level of agreement. Participants indicated how many months/years they had worked with their boss or Relational leadership and employee creativity Table 1. Non-managerial/nonsupervisory staff demographic of Cape Coast-Elmina conurbation hotels JHTI supervisor to calculate leader–follower dyadic tenure and the hotel grades were obtained from Ghana Tourism Authority. We controlled for self-efficacy and hotel rating. High self-efficacy, according to Bandura (1986), influences motivation and the capacity to engage in particular behaviours, making it a crucial condition for personal creativity. Abuelhassan and AlGassim (2022) postulated that employees who perceive themselves to be competent are more capable of meeting diverse job demands because they also tend to be very creative. Empirical research shows that individuals with high levels of self-efficacy frequently provide novel concepts and solutions (De Jesus et al., 2013). Also, we reasoned that employees in higher star rating hotels could be more creative than those in lower star rating hotels because highly graded hotels are more likely to have organizational resources to support their creativity. Data analysis Before the data gathered were analysed, it was essential to determine its suitability. Hence, using WarnPLS Version 7.0 of partial least squares structural equation modelling (SEM), we examined the validity and reliability of the items used in the study (Chin, 1998; Kock, 2017; Moqbel et al., 2013). Three things were tested for: convergent validity, reliability and discriminant validity. Table 2 provides the CFA, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability and average variance extracted data. The interpretation of the mediation results is based on the postulation of Hayes (2013). The author argued that it was still possible to have a significant mediation effect if only one of the paths are significant because the mediation effect is the product of the a-path and b-path. Therefore, even if one of the direct paths is insignificant, the indirect path may still be significant. Results Reliability, validity and common method variance analyses Measures of reliability included Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. All the composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were above the 0.7 cut-off point suggested by Hair et al. (2017). The average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF), which is 1946, and the variance inflation factors (VIFs), all of which are less than 3, show that collinearity is not a concern in the models under examination (Kock, 2011). The results demonstrate that the instruments had sufficient convergent validity and reliability because the items, respectively, had strong and significant loadings on the constructs (Hair et al., 2010). Common method variance The likelihood of variance in the measurement model was determined by evaluating common method bias through Harman’s one-factor test (Baron and Tang, 2009). Only 17.3% of the data variation was explained by the first unrotated factor. As a result, no single component emerged, and the primary factor did not fully explain the variance (less than 50%). Therefore, it appears unlikely that the results are impacted by common technique variance in light of these findings. Results and hypothesis testing The results of the structural paths, represented in Figure 2, demonstrate that there was a positive and significant association between relational leadership and employee creativity (5 0.12, p 0.10), supporting hypothesis 1. Relational leadership and knowledge-sharing behaviour had a positive and significant association (r 5 0.37, p 0.05.) Therefore, H2 is supported. The results show that knowledge-sharing behaviour did not influence employee creativity (β 5 0.03, p > 0.10). Thus, H3 is not supported. Furthermore, the inclusion of Construct Items Relational Leadership α 5 0.96; CR 5 0.97; AVE 5 0.54 Creates opportunities for professional and personal growth 0.75 Encourages risk-taking amongst staff Engages in well-mannered, polite, civil discourse that respects differences and values equity and involvement Readily maintains attitudes that respect differences and values equity and involvement Recognizes and engages all internal and external stakeholders in building coalitions Builds the professional capabilities of others and promotes selfleadership Encourages others by sharing information bringing people into the group process and promoting individual and group learning Shares important tasks with others Acknowledges the abilities and skills of others Shows appreciation for the contribution of others Steps out of his/her frame of reference into that of others Shows sensitivity to the needs and feelings of employees Establishes relationships built on values, caring and support Promotes individual development and responds to the needs of others Nurtures growth and remains connected to staff, through interpersonal relationships Influences others by mutual liking and respect Conforms to the established standards of administrative practice Actively practices “leading with integrity” Considers opposing viewpoints and the values and the values of others in decision-making Encourages a shared process of leadership through the creation of opportunity and responsibility for others Provides inspiring and strategic goals Inspirational, able to motivate by articulating effectively the Importance of what staff are doing Has vision; often brings ideas about possibilities for the future Articulates natural mental ability that is associated with the experience Often exhibit unique behaviour that symbolizes deeply held beliefs My immediate manager or supervisor often shares: 0.67 0.65 Knowledge-sharing Behaviour α 5 0.93; CR 5 0.94; AVE 5 0.53 Business official documents, proposals or reports with me Business manuals, models and methodologies with me Stories of success and failure with me Business knowledge obtained from newspapers, magazines, television or the internet with me Know-how work experiences with me Knowledge obtained from instruction or training with me Problem-solving knowledge with me I often ask my immediate manager or supervisor: To share business official documents, proposals or reports, when necessary To share business manuals, models and methodologies, when necessary Loadings Relational leadership and employee creativity 0.76 0.75 0.73 0.69 0.73 0.74 0.68 0.76 0.75 0.73 0.78 0.75 0.74 0.81 0.79 0.70 0.74 0.72 0.76 0.73 0.68 0.75 0.68 0.65 0.71 0.66 0.69 0.71 0.55 0.76 0.78 (continued ) Table 2. Reliability and convergent validity factor analysis of constructs JHTI Construct Employee Creativity α 5 0.91; CR 5 0.93 AVE 5 0.61 Self-Efficacy α 5 0.93; CR 5 0.95 AVE 5 0.68 Hotel Grade α 5 1.00; CR 5 1.00; Table 2. AVE 5 1.00 Leader-Follower Dyadic Tenure α 5 1.00; CR 5 1.00; AVE 5 1.00 Items To share stories of success or failure, when necessary To share business knowledge obtained from newspapers, magazines, television or the Internet, when necessary To share know-how from work experiences, when necessary To share knowledge gained from instruction or training when necessary To share problem-solving knowledge I am a creative problem-solver I use my creative abilities when faced with challenges I take risks with my ideas I am comfortable with others critiquing my ideas I always think of new ways to do things It is easy for me to think of many ideas when looking for an answer to a question I tend to do things that are unusual for most people I always stand out in a crowd I do not avoid difficult tasks I am a very determined person Once I set my mind to a task almost nothing can stop me I have a lot of self-confidence I am at my best when I am challenged I believe that it is shameful to give up something I started Things always seem worth the effort I do not find it difficult to take risks Which of these Ghana Tourist Board classifications does your Hotel belong to currently? For how long have you worked with your immediate supervisor? Loadings 0.82 0.77 0.82 0.79 0.72 0.79 0.83 0.79 0.79 0.83 0.78 0.75 0.70 0.83 0.85 0.85 0.85 0.82 0.80 0.79 0.82 1.00 1.00 knowledge-sharing behaviour as a mediation variable between the relationship between relational leadership and employee creativity showed a positive and significant effect (β 5 0.37, p < 0.05). This supports H4. Finally, leader–follower dyadic tenure did not have a moderating effect on the nexus between relational leadership and knowledge-sharing behaviour (β 5 0.06, p > 0.10). This does not support H5 (See Table 3). Discussion and conclusions Conclusions Despite frantic efforts and investments, organizations are struggling with how to improve employees’ creativity, particularly, organizations in the hospitality industry. Therefore, this study examined the direct and indirect effects of relational leadership on employee creativity among hospitality organizations in Ghana. This study adds to the body of evidence supporting earlier research on how leader knowledge-sharing behaviour affects employee creativity at work. We found that relational leadership has a positive effect on knowledgesharing behaviour and employee creativity. Further, knowledge-sharing behaviour mediated the relationship between relational leadership and employee creativity, although knowledgesharing behaviour did not have a significant effect on employee creativity. Finally, this study showed that leader–follower tenure does not play any vital role on the relationship between relational leadership and employee creativity. ES (F)8i LFDT (F)1i KSB (F)14i 2 R = 0.15 β = –0.06 (P = 0.13) β = 0.37 (P < 0.01) β = 0.76 (P < 0.01) β = –0.03 (P = 0.32) EC (F)8i β = 0.12 2 R = 0.71 (P = 0.01) RL (F)25i β = 0.02 (P = 0.35) HG (F)1i Structural path Relational leadership and employee creativity Beta(R) Total effect Std. deviation p-value Decision Control variables Self-efficacy → EC Hotel-grade → EC 0.76 0.021 0.65 0.003 0.048 0.053 0.001** 0.348 Direct effects RL → EC RL →KSB KSB → EC 0.12 0.37 0.025 0.07 0.144 0.01 0.052 0.050 0.053 0.012* 0.001** 0.318 H1 5 supported H2 5 supported H3 5 Not supported Moderating effect RL 3 LDT 3 KSB 0.06 0.011 0.053 0.13 H4 5 Not supported Mediating effect RL → LDT → EC 0.37 0.000 0.054 0.001** Note(s): *Significance at 0.10, **significance at 0.05, ***significance at 0.01 Figure 2. Path diagram showing path coefficients and variance H5 5 supported Theoretical implications This study contributes to the literature in several ways. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to contribute to social exchange theory by demonstrating the connections among relational leadership, leader–follower dyadic tenure, knowledge-sharing behaviour and employee creativity in the hospitality industry. Another unique contribution of our study to the extant literature on the effects of leadership styles on employee behaviour in the hospitality industry is our findings addressing the intervening role of follower–leader dyadic tenure. Prior related investigations have been limited to knowledge-sharing behaviour (Al Hawamdeh, 2022), service climate (Ling et al., 2016) and unit identification (Liden et al., 2014), failing to address the thorny question of whether leader–follower dyadic tenure influences employee creative behaviour. Our results showed that leader–follower dyadic tenure does not strengthen the Table 3. Summary of results JHTI relationship between relational leadership and knowledge-sharing behaviour. This is because the hospitality industry in Ghana is characterized by high labour turnover rate because the sector is labour-intensive, pays low salaries and provides minimal opportunities for career advancement (Amissah et al., 2016). Again, De Gilder (2003) argued that some leaders are simply more powerful, more resourceful and better positioned. This allows such leaders to provide highquality exchanges with their followers, including insightful information or knowledge irrespective of the leader–member follower dyadic tenure. In the same way, followers who may have initially recognized the advantages of their leaders’ relationships may eventually become less reliant on the leader since they may have established an informal network that serves as alternate sources of information (Liden et al., 1997). Third, our study emphasized that positive leadership styles do not only advance knowledge management literature but they are also important channels for promoting employee creative behaviours (Ansong et al., 2022). Our findings support the view that high-quality interaction between leaders and followers in the hospitality industry promotes employee creativity as they feel indebted and seek diverse means to ensure the sustenance of their organizations (Akgunduz et al., 2022). Fundamentally, relational leadership has been conceptualised as a social context that is full of integrated and interwoven interactions, carried out by the sharing of information (Wiig, 1999). Relational leaders respect employees’ opinions in decision-making and share valued resources which could promote employee creativity (Mo et al., 2019). This study enriches and advances previous studies on job embeddedness and dedication (Akgunduz et al., 2022), work engagement (Al Hawamdeh, 2022; Vakira et al., 2022) and civic virtue behaviour (Khan et al., 2020). Finally, this study revealed the mediating role of knowledge-sharing behaviour on the link between relational leadership and employee creativity, thus indicating how relational leadership behaviours transfers to employees’ creative behaviour. The results demonstrated that knowledge-sharing behaviour mediates the link between relational leadership and employee creativity. Le and Lei (2019) asserted that leaders who develop appropriate climate for knowledge-sharing behaviour, in turn, enhance creativity. The inclusive nature of relational leadership develops the strengths and talents of followers to creatively contribute to organizational goals (Komives et al., 2009). Practical implications This study examined the need for hotel managers to adopt relational leadership style to enhance knowledge-sharing behaviour and employee creativity from the lens of social exchange theory (Blau, 1964). We proffer the following suggestions for hotel supervisors to implement based on the findings of the study. First, hotel supervisors should adopt relational leadership behaviours. They must delegate and empower employees to act freely. For instance, employees could be given the opportunity to serve guests without necessarily waiting for the approval of their superiors. Employees with new ideas with regard to new products or services should be given the necessary support to execute these ideas. Beyond the usual first day of the week meetings held to assign roles and responsibilities, managers should also develop a ritual of holding weekly informal discussions with employees during break periods to share personal and other work-related experiences. Supervisors should promote inclusiveness and collaboration by assigning group assignments and rewards. This could enhance workplace friendship and knowledge-sharing and create a synergetic environment necessary for employee creativity. Occasionally, supervisors may allow the family of employees to visit them at the workplace to appreciate the nature of their work. Hotel managers should address the needs of their employees by providing family-supportive facilities and professional growth opportunities and improving working conditions. Finally, we recommend that hotels should employ persons with good human relations as supervisors. They should also invest in regular professional training programmes to enhance the human relation skills of supervisors. Furthermore, hotels should designate only supervisors with good human relations for training and knowledge-sharing assignments since the act of stimulating employee creativity goes beyond the mere provision of information. Employee creativity requires the warmth and care of persons that supply such information and knowledge. With regard to knowledge-sharing, managers should be prepared to share their personal experiences and information with employees. This could encourage employees to freely express their views and suggest ways for improving products, services and work procedures. Employees that suggest good ideas should be recognized and rewarded publicly. Limitations and future research First, the study employed a cross-sectional design. This design cannot be used to establish causal relationships among the variables. Future research might use a longitudinal design to draw causal inferences from the model. Second, while this study looked at a potential mediator in the connection between relational leadership and employee creativity, it neglected to take into account other crucial factors such as organizational practices, cultures, knowledge acquisition and knowledge integration. Given that these factors have the potential to play an intervening role in the relationship between relational leadership and employee creativity, future research can build on this study by taking them into account. Third, since data were collected only from employees in the hospitality industry at the Cape Coast-Elmina conurbation of Ghana, the findings may not apply to other sectors and geographical locations. Hence, it will be fruitful for future researchers to consider other sectors and geographical locations to validate our findings. Finally, the study also runs the risk of common method bias because it is based on self-reported data. However, we did not find a common method variance to be a significant issue in this study, according to our tests. The correctness of the data and the conclusions were supported by the study’s use of several assessments such as Cronbach alphas, composite reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity. To improve the research design, future studies may include objective measures for employee creativity. References Abuelhassan, A.E. and AlGassim, A. (2022), “How organizational justice in the hospitality industry influences proactive customer service performance through general self-efficacy”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 34 No. 7, pp. 2579-2596. Adam, A.M. (2020), “Sample size determination in survey research”, Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 90-97. Adu-Ampong, E. (2018), “Tourism and national economic development planning in Ghana, 1964-2014”, International Development Planning Review, Vol. 40 No. 1, pp. 75-95. Akgunduz, Y., Turksoy, S.S. and Nisari, M.A. (2022), “How leader–member exchange affects job embeddedness and job dedication through employee advocacy”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. Akhavan, P., Hosseini, S.M., Abbasi, M. and Manteghi, M. (2015), “Knowledge-sharing determinants, behaviours, and innovative work behaviours: an integrated theoretical view and empirical examination”, Aslib Journal of Information Management, Vol. 6 No. 5, pp. 562-591. Al Hawamdeh, N. (2022), “The influence of humble leadership on employees’ work engagement: the mediating role of leader knowledge-sharing behaviour”, VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. Amabile, T.M. and Pratt, M.G. (2016), “The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: making progress, making meaning”, Research in Organizational Behaviour, Vol. 36, pp. 157-183. Relational leadership and employee creativity JHTI Amissah, E.F., Gamor, E., Deri, M.N. and Amissah, A. (2016), “Factors influencing employee job satisfaction in Ghana’s hotel industry”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 166-183. Ampong, G.O.A., Abubakari, A., Mohammed, M., Appaw-Agbola, E.T., Addae, J.A. and Ofori, K.S. (2021), “Exploring customer loyalty following service recovery: a replication study in the Ghanaian hotel industry”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. 4 No. 5, pp. 639-657. Amundsen, S. and Martinsen, Ø.L. (2014), “Empowering leadership: construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale”, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 487-511. Ansong, A., Agyeiwaa, A.A. and Gnankob, R.I. (2022), “Responsible leadership, job satisfaction and duty orientation: lessons from the manufacturing sector in Ghana”, European Business Review, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. Baafi, F., Ansong, A., Dogbey, K.E. and Owusu, N.O. (2021), “Leadership and innovative work behaviour within Ghanaian metropolitan assemblies: mediating role of resource supply”, International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 34 No. 7, pp. 765-784. Bandura, A. (1986), Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory, PrenticeHall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Bani-Melhem, S., Zeffane, R. and Albaity, M. (2018), “Determinants of employees’ innovative behaviour”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 30 No. 3, pp. 1601-1602. Bargeman, B., Richards, G. and Govers, E. (2018), “Volunteer tourism impacts in Ghana: a practice approach”, Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 21 No. 13, pp. 1486-1501. Baron, R.A. and Tang, J. (2009), “Entrepreneurs’ social skills and new venture performance: mediating mechanisms and cultural generality”, Journal of Management, Vol. 35 No. 2, pp. 282-306. Bass, B.M. and Avolio, B.J. (1995), MLQ: Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, 2nd ed., Mind Garden, Redwood City, CA. Bavik, Y.L., Tang, P.M., Shao, R. and Lam, L.W. (2018), “Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: exploring dual-mediation paths”, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 322-332. Bhutto, T.A., Farooq, R., Talwar, S., Awan, U. and Dhir, A. (2021), “Green inclusive leadership and green creativity in the tourism and hospitality sector: serial mediation of green psychological climate and work engagement”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 29 No. 10, pp. 1716-1737. Blau, P.M. (1964), “Justice in social exchange”, Sociological Iinquiry, Vol. 34 No. 2, pp. 193-206. Boateng, H., Okoe, A.F. and Hinson, R.E. (2018), “Dark tourism: exploring tourist’s experience at the Cape Coast Castle, Ghana”, Tourism Management Perspectives, No. 27, pp. 104-110. Bonner, J.M., Greenbaum, R.L. and Mayer, D.M. (2016), “My boss is morally disengaged: the role of ethical leadership in explaining the interactive effect of supervisor and employee moral disengagement on employee behaviours”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 137 No. 4, pp. 731-742. Breevaart, K. and de Vries, R.E. (2021), “Followers’ HEXACO personality traits and preference for charismatic, relationship-oriented, and task-oriented leadership”, Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 36 No. 2, p. 256. Carifio, J. (2010), “Development and validation of a measure of relational leadership: implications for leadership theory and policies”, Current Research in Psychology, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 16-28. Carmeli, A. and Spreitzer, G.M. (2009), “Trust, connectivity, and thriving: implications for innovative behaviour at work”, The Journal of Creative Behaviour, Vol. 43 No. 3, pp. 169-191. Chen, G., Gully, S.M. and Eden, D. (2001), “Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale”, Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 4 No. 1, p. 79. Chin, W.W. (1998), “The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling”, Modern Methods for Business Research, Vol. 295 No. 2, pp. 295-336. Creswell, J.W. (2014), A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research, SAGE publications, London. Danvour, F., Adongo, C.A., Amuquando, F.E. and Adam, I. (2021), “Managin the COVID-19 crisis: coping and post-recovery strategies for hospitality and tourism businesses in Ghana”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 373-392. Dayour, F. (2014), “Are backpackers a homogeneous segment? A study of backpackers’ motivations in the Cape Coast-Elmina conurbation, Ghana”, Tourismos, Vol. 9 No. 2, p. 108. Dayour, F., Adongo, C.A. and Taale, F. (2016), “Determinants of backpackers’ expenditure”, Tourism Management Perspectives, No. 17, pp. 36-43. De Gilder, D. (2003), “Commitment, trust and work behaviour: the case of contingent workers”, Personnel Review, Vol. 32 No. 5, pp. 588-604. De Jong, J.P. and Den Hartog, D.N. (2007), “How leaders influence employees’ innovative behaviour”, European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 41-64. De Jesus, S.N., Rus, C.L., Lens, W. and Imaginario, S. (2013), “Intrinsic motivation and creativity related to product: a meta-analysis of the studies published between 1990-2010”, Creativity Research Journal, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 80-84. De Vries, R.E., Van den Hooff, B. and De Ridder, J.A. (2006), “Explaining knowledge sharing: the role of team communication styles, job satisfaction, and performance beliefs”, Communication Research, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 115-135. Dillette, A. (2021), “Roots tourism: a second wave of double consciousness for African Americans”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 29 Nos 2-3, pp. 412-427. Elkhwesky, Z., Salem, I.E., Ramkissoon, H. and Casta~ neda-Garcıa, J.-A. (2022), “A systematic and critical review of leadership styles in contemporary hospitality: a roadmap and a call for future research”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 34 No. 5, pp. 1925-1958. Ferch, S.R. and Mitchell, M.M. (2001), “Intentional forgiveness in relational leadership: a technique for enhancing effective leadership”, Journal of Leadership Studies, Vol. 7 No. 4, pp. 70-83. Gerstein, M. and Friedman, H.H. (2017), “A new corporate ethics and leadership paradigm for the age of creativity”, Journal of Accounting, Ethics and Public Policy, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 179-180. Gnankob, R.I., Ansong, A. and Issau, K. (2022), “Servant leadership and organizational citizenship behaviour: the role of public service motivation and length of time spent with the leader”, International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 35 No. 2, pp. 236-253. Gouldner, A.W. (1960), “The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 161-167. Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Balin, B.J. and Anderson, R.E. (2010), Multivariate and Data Analysis, International Editions, Maxwell Macmillan, New York. Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M. and Thiele, K.O. (2017), “Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modelling methods”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 45 No. 5, pp. 616-632. Hassi, A. (2019), “Empowering leadership and management innovation in the hospitality industry context: the mediating role of climate for creativity”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 1785-1800. Hayes, A.F. (2013), Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, Guilford Press, New York, NY. Hensley, N. (2020), “Educating for sustainable development: cultivating creativity through mindfulness”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 243, 118542. Hollander, E. (2012), Inclusive Leadership: The Essential Leader-Follower Relationship, Routledge, New York. Relational leadership and employee creativity JHTI Jada, U.R., Mukhopadhyay, S. and Titiyal, R. (2019), “Empowering leadership and innovative work behaviour: a moderated mediation examination”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 915-930. Javed, B., Naqvi, S.M.M.R., Khan, A.K., Arjoon, S. and Tayyeb, H.H. (2017), “Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behaviour: the role of psychological safety–corrigendum”, Journal of Management and Organization, Vol. 23 No. 3, p. 472. Jian, G. and Dalisay, F. (2017), “Conversation at work: the effects of leader-member conversational quality”, Communication Research, Vol. 44 No. 2, pp. 177-197. Khalid, S. and Zubair, A. (2014), “Emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, and creativity among employees of advertising agencies”, Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 203-221. Khan, N.A., Khan, A.N., Soomro, M.A. and Khan, S.K. (2020), “Transformational leadership and civic virtue behaviour: valuing act of thriving and emotional exhaustion in the hotel industry”, Asia Pacific Management Review, Vol. 25 No. 4, pp. 216-225. Kim, M. and Beehr, T.A. (2018), “Can empowering leaders affect subordinates’ well-being and careers because they encourage subordinates’ job crafting behaviours?”, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 184-196. Kim, T.T. and Lee, G. (2013), “Hospitality employee knowledge-sharing behaviours in the relationship between goal orientations and service innovative behaviour”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 34 No. 1, pp. 324-337. Kim, M.S., Phillips, J.M., Park, W.W. and Gully, S.M. (2021), “When leader-member exchange leads to knowledge sharing: the roles of general self-efficacy, team leader modeling, and LMX differentiation”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 1-28. Kock, N. (2011), “Using WarpPLS in e-collaboration studies: mediating effects, control and second order variables, and algorithm choices”, International Journal of E-Collaboration (IJeC), Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 1-13. Kock, N. (2017), “Common method bias: a full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM”, Partial Least Squares Path Modeling, Springer, Cham, pp. 245-257. Komives, S.R., Lucas, N. and McMahon, T.R. (2009), Exploring Leadership: For College Students Who Want to Make a Difference, John Wiley & Sons, San Francisco, p. 368. Lan, J., Wong, C.-S. and Wong, I.A. (2022), “The role of knowledge sharing in hotel newcomer socialization: a formal intervention program”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 34 No. 6, pp. 2250-2271. Le, P.B. and Lei, H. (2019), “Determinants of innovation capability: the roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing and perceived organizational support”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 527-547. Lee, J.N. (2001), “The impact of knowledge sharing, organizational capability and partnership quality on IS outsourcing success”, Information and Management, Vol. 38 No. 5, pp. 323-335. Lee, C., Hallak, R. and Sardeshmukh, S.R. (2019), “Creativity and innovation in the restaurant sector: supply-side processes and barriers to implementation”, Tourism Management Perspectives, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 54-55. Lewicki, R.J. and Bunker, B.B. (1996), “Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships”, Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, Vol. 114 No. 1, p. 139. Liao, S.H., Chen, C.C. and Hu, D.C. (2018), “The role of knowledge sharing and LMX to enhance employee creativity in theme park work team: a case study of Taiwan”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 30 No. 5, pp. 2343-2359. Liden, R.C., Sparrowe, R.T. and Wayne, S.J. (1997), “Leader-member exchange theory: the past and potential for the future”, Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, No. 15, pp. 47-120. Liden, R.C., Wayne, S.J., Liao, C. and Meuser, J.D. (2014), “Servant leadership and serving culture: influence on individual and unit performance”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 57 No. 5, pp. 1434-1452. Lindebaum, D., Geddes, D. and Gabriel, Y. (2017), “Moral emotions and ethics in organizations: introduction to the special issue”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 141 No. 4, pp. 645-656. Ling, Q., Lin, M. and Wu, X. (2016), “The trickle-down effect of servant leadership on frontline employee service behaviours and performance: a multilevel study of Chinese hotels”, Tourism Management, Vol. 52, pp. 341-368. Liu, X., Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., Dai, O. and Lu, J. (2010), “Human mobility and international knowledge spillovers: evidence from high-tech small and medium enterprises in an emerging market”, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 340-355. Mensah, E.A., Agyeiwaah, E. and Dimache, A.O. (2017), “Will their absence make a difference? The role of local volunteer NGOs in home-stay intermediation in Ghana’s Garden City”, International Journal of Tourism Cities, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 69-86. Mo, S., Ling, C.D. and Xie, X.Y. (2019), “The curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and team creativity: the moderating role of team fault lines”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 154 No. 1, pp. 229-242. Moqbel, M., Nevo, S. and Kock, N. (2013), “Organizational members’ use of social networking sites and job performance: an exploratory study”, Information Technology and People, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 240-264. Mota Veiga, P., Fernandes, C. and Ambrosio, F. (2022), “Knowledge spillover, knowledge management and innovation of the Portuguese hotel industry in times of crisis”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. Nasifoglu Elidemir, S., Ozturen, A. and Bayighomog, S.W. (2020), “Innovative behaviours, employee creativity, and sustainable competitive advantage: a moderated mediation”, Sustainability, Vol. 12 No. 8, p. 3295. Nham, T.P., Nguyen, T.M., Tran, N.H. and Nguyen, H.A. (2020), “Knowledge sharing and innovation capability at both individual and organizational levels: an empirical study from Vietnam’s telecommunication companies”, Management and Marketing, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 275-301. Nieves, J. and Diaz-Meneses, G. (2018), “Knowledge sources and innovation in the hotel industry”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 30 No. 6, pp. 2537-2561. Northouse, P.G. (2019), Leadership: Theory and Practice, 8th ed., SAGE Publications, Los Angeles. Phung, V.D., Hawryszkiewycz, I., Chandran, D. and Ha, B.M. (2017), “Knowledge sharing and innovative work behaviour: a case study from Vietnam”, ACIS 2017 Proceedings, p. 91. Shukla, B., Sufi, T., Joshi, M. and Sujatha, R. (2022), “Leadership challenges for Indian hospitality industry during COVID-19 pandemic”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. aheadof-print No. ahead-of-print. Straub, D., Boudreau, M.C. and Gefen, D. (2004), “Validation guidelines for IS positivist research”, Communications of the Association for Information Systems, Vol. 13 No. 1, p. 24. Thuan, L.C. (2020), “The role of supervisor knowledge-sharing behaviour in stimulating subordinate creativity”, VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, Vol. 50 No. 4, pp. 597-613. Tu, M., Cheng, Z. and Liu, W. (2019), “Spotlight on the effect of workplace ostracism on creativity: a social cognitive perspective”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 10 No. 1, p. 1215. Vakira, E., Shereni, N.C., Ncube, C.M. and Ndlovu, N. (2022), “The effect of inclusive leadership on employee engagement, mediated by psychological safety in the hospitality industry”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. Relational leadership and employee creativity JHTI Van Den Hooff, B. and De Ridder, J.A. (2004), “Knowledge sharing in context: the influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 8 No. 6, pp. 117-130. Venckut_e, M., Mulvik, I.B., Lucas, B. and Kampylis, P. (2020), “Creativity–a transversal skill for lifelong learning. An overview of existing concepts and practices”, JRC Working Papers, (JRC122016). Wang, C.J., Tsai, H.T. and Tsai, M.T. (2014), “Linking transformational leadership and employee creativity in the hospitality industry: the influences of creative role identity, creative selfefficacy, and job complexity”, Tourism Management, Vol. 40, pp. 79-89. Wang, X., Wen, X., Pa$samehmetog!lu, A. and Guchait, P. (2021), “Hospitality employee’s mindfulness and its impact on creativity and customer satisfaction: the moderating role of organizational error tolerance”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 94, pp. 1-11. Wayne, S.J., Shore, L.M. and Liden, R.C. (1997), “Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: a social exchange perspective”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40 No. 1, pp. 82-111. Wiig, K.M. (1999), “Introducing knowledge management into the enterprise”, Knowledge Management Handbook, CRC Press, New York, pp. 3.1-3.41. Yang, J.T. and Wan, C.S. (2004), “Advancing organizational effectiveness and knowledge management implementation”, Tourism Management, Vol. 25 No. 5, pp. 593-601. Yankholmes, A. (2018), “Tourism as an exercise in three-dimensional power: evidence from Ghana”, Tourism Management Perspectives, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 1-12. Yankholmes, A. and McKercher, B. (2015), “Understanding visitors to slavery heritage sites in Ghana”, Tourism Management, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 22-32. Zhou, J. and Hoever, I.J. (2014), “Research on workplace creativity: a review and redirection”, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, Vol. 1 No. 1, p. 334. Zhou, J., Oldham, G.R., Chuang, A. and Hsu, R.S. (2022), “Enhancing employee creativity: effects of choice, rewards and personality”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 107 No. 3, pp. 503-513. Zona, M.A. and Adrian, A. (2020), “Innovation and employee creativity in hospitality industry in west Sumatra”, 4th Padang International Conference on Education, Economics, Business and Accounting (PICEEBA-2 2019), Atlantis Press, pp. 767-773. Further reading Amabile, T.M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, L. and Herron, M. (1996), “Assessing the work environment for creativity”, The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 4 No. 39, pp. 154-184. Chiang, C.F. and Chen, J.A. (2021), “How empowering leadership and a cooperative climate influence employees’ voice behaviour and knowledge sharing in the hotel industry”, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 476-495. Choi, S.B., Tran, T.B.H. and Park, B.I. (2015), “Inclusive leadership and work engagement: mediating roles of affective organizational commitment and creativity”, Social Behaviour and Personality: An International Journal, Vol. 43 No. 6, pp. 931-943. Hansen, M.T., Mors, M.L. and Løv as, B. (2005), “Knowledge sharing in organizations: multiple networks, multiple phases”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 48 No. 5, pp. 776-793. Hollander, E.P. (2014), “Leader-follower relations and the dynamics of inclusion and idiosyncrasy credit”, Conceptions of Leadership, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp. 201-221. Jung, D.I. (2001), “Transformational and transactional leadership and their effects on creativity in groups”, Creativity Research Journal, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 185-195. Regan, H.B. and Brooks, G.H. (1995), Out of Women’s Experience: Creating Relational Leadership, Corwin Press, CA. Corresponding author Abraham Ansong can be contacted at: aansong@ucc.edu.gh For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com View publication stats Relational leadership and employee creativity