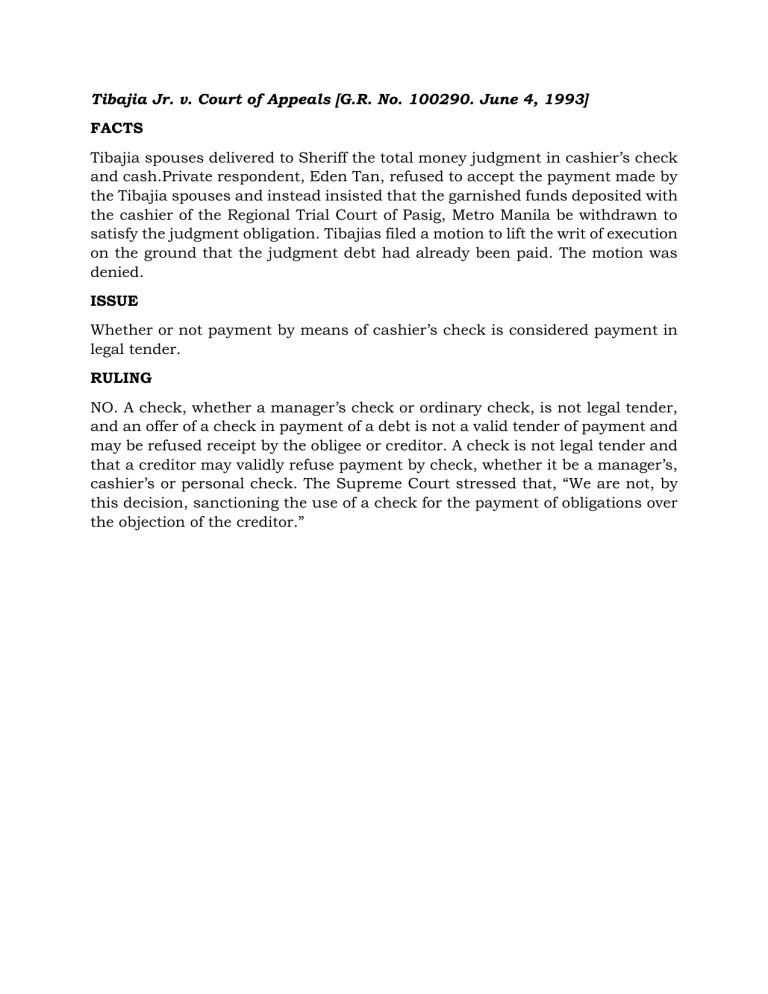

Tibajia Jr. v. Court of Appeals [G.R. No. 100290. June 4, 1993] FACTS Tibajia spouses delivered to Sheriff the total money judgment in cashier’s check and cash.Private respondent, Eden Tan, refused to accept the payment made by the Tibajia spouses and instead insisted that the garnished funds deposited with the cashier of the Regional Trial Court of Pasig, Metro Manila be withdrawn to satisfy the judgment obligation. Tibajias filed a motion to lift the writ of execution on the ground that the judgment debt had already been paid. The motion was denied. ISSUE Whether or not payment by means of cashier’s check is considered payment in legal tender. RULING NO. A check, whether a manager’s check or ordinary check, is not legal tender, and an offer of a check in payment of a debt is not a valid tender of payment and may be refused receipt by the obligee or creditor. A check is not legal tender and that a creditor may validly refuse payment by check, whether it be a manager’s, cashier’s or personal check. The Supreme Court stressed that, “We are not, by this decision, sanctioning the use of a check for the payment of obligations over the objection of the creditor.” Philippine Airlines v. Court of Appeals [G.R. No. L-49188. January 30, 1990] FACTS Amelia Tan was found to have been wronged by Philippine Air Lines (PAL). She filed her complaint in 1967. After ten (10) years of protracted litigation in the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeals, Ms. Tan won her case. Almost twenty-two (22) years later, Ms. Tan has not seen a centavo of what the courts have solemnly declared as rightfully hers. Through absolutely no fault of her own, Ms. Tan has been deprived of what, technically, she should have been paid from the start, before 1967, without need of her going to court to enforce her rights. And all because PAL did not issue the checks intended for her, in her name. Petitioner PAL filed a petition for review on certiorari the decision of Court of Appeals dismissing the petition for certiorari against the order of the Court of First Instance (CFI) which issued an alias writ of execution against them. Petitioner alleged that the payment in check had already been effected to the absconding sheriff, satisfying the judgment. ISSUE Whether or not payment by check to the sheriff extinguished the judgment debt. RULING NO. The payment made by the petitioner to the absconding sheriff was not in cash or legal tender but in checks. The checks were not payable to Amelia Tan or Able Printing Press but to the absconding sheriff.In the absence of an agreement, either express or implied, payment means the discharge of a debt or obligation in money and unless the parties so agree, a debtor has no rights, except at his own peril, to substitute something in lieu of cash as medium of payment of his debt. Strictly speaking, the acceptance by the sheriff of the petitioner’s checks, in the case at bar, does not, per se, operate as a discharge of the judgment debt. The check as a negotiable instrument is only a substitute for money and not money, the delivery of such an instrument does not, by itself, operate as payment. A check, whether a manager’s check or ordinary cheek, is not legal tender, and an offer of a check in payment of a debt is not a valid tender of payment and may be refused receipt by the obligee or creditor. Mere delivery of checks does not discharge the obligation under a judgment. The obligation is not extinguished and remains suspended until the payment by commercial document is actually realized (Art. 1249, Civil Code, par. 3). Caltex Inc. v. Court of Appeals [G.R. No. 97753. August 10, 1992] FACTS On various dates, Security Bank and Trust Company (SBTC), through its Sucat Branch issued 280 certificates of time deposit (CTD) in favor of one Angel dela Cruz who later lost them. Date of Maturity FEB. 23, 1984 FEB 22, 1982, 19____ This is to Certify that B E A R E R has deposited in this Bank the sum of PESOS: FOUR THOUSAND ONLY, SECURITY BANK SUCAT OFFICE P4,000& 00 CTS Pesos, Philippine Currency, repayable to said depositor 731 days. after date, upon presentation and surrender of this certificate, with interest at the rate of 16% per cent per annum. (Sgd. Illegible) Caltex (Phils.) Inc. went to the SBTC Sucat branch and presented for verification the CTDs declared lost by Angel dela Cruz alleging that the same were delivered to herein plaintiff “as security for purchases made with Caltex Philippines, Inc.” by said depositor. SBTC rejected Caltex’s demand and claim. Caltex sued SBTC but case was dismissed rationalizing that CTD’s are non-negotiable instruments. ISSUE Whether or not Certificate of Time Deposit (CTD) is a negotiable instrument. RULING YES. The CTDs in question undoubtedly meet the requirements of the law for negotiability under Section 1 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. The accepted rule is that the negotiability or non-negotiability of an instrument is determined from the writing, that is, from the face of the instrument itself. In the construction of a bill or note, the intention of the parties is to control, if it can be legally ascertained. Here, if it was really the intention of respondent bank to pay the amount to Angel de la Cruz only, it could have with facility so expressed that fact in clear and categorical terms in the documents, instead of having the word “BEARER” stamped on the space provided for the name of the depositor in each CTD. While the writing may be read in the light of surrounding circumstances in order to more perfectly understand the intent and meaning of the parties, yet as they have constituted the writing to be the only outward and visible expression of their meaning, no other words are to be added to it or substituted in its stead. Metropolitan Bank and Trust Co. v. Court of Appeals [G.R. No. 88866. February 18, 1991] FACTS Various treasury warrants drawn by the Philippine Fish Marketing Authority were subsequently indorsed by Golden Savings. Petitioner allowed Golden Savings to withdraw thrice from uncleared treasury warrants as the former was exasperated over persistent inquiries of the latter after one week. Warrants were later dishonored by the Bureau of Treasury. ISSUE (a) Whether or not treasury warrants are negotiable instruments. (b) Whether or not petitioner’s negligence would bar them for recovery. RULING (a) NO. The indication of fund as the source of the payment to be made on the treasury warrants makes the order or promise to pay “not unconditional” and the warrants themselves non-negotiable. Metrobank cannot contend that by indorsing the warrants in general, Golden Savings assumed that they were “genuine and in all respects what they purport to be,” in accordance with Section 66 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. The simple reason is that this law is not applicable to the non-negotiable treasury warrants. (b) YES. Metrobank was indeed negligent in giving Golden Savings the impression that the treasury warrants had been cleared and that, consequently, it was safe to allow Gomez to withdraw the proceeds thereof from his account with it. Without such assurance, Golden Savings would not have allowed the withdrawals; with such assurance, there was no reason not to allow the withdrawal. However, withdrawals released after the notice of the dishonor may be debited as it will result to unjust enrichment. Ang Tek Lian v. Court of Appeals [G.R. No. L-2516. September 25, 1950] FACTS Petitioner drew a check payable to the order of “cash” knowing that he had no funds. He delivered it in exchange of money. Petitioner was found guilty of estafa, but petitioner argued that the check had not been indorsed by him, hence, he should not be held guilty thereof. ISSUE Whether or not indorsement is necessary to negotiate a check payable to the order of “cash”. RULING NO. Indorsement is no longer necessary. Under the Negotiable Instruments Law (Sec. 9 [d]), a check drawn payable to the order of “cash” is a check payable to bearer, and the bank may pay it to the person presenting it for payment without the drawer’s indorsement. Being a bearer instrument, negotiation may be done by mere delivery of the instrument. PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK (PNB) vs. RODRIGUEZ G.R. No. 170325 September 26, 2008 FACTS: Respondents-Spouses Rodriguez maintained savings and demand/checking accounts with petitioner. In line with their informal lending business, they had a discounting arrangement with PEMSLA, an association of PNB employees, which regularly granted loans to its members. Spouses Rodriguez would rediscount the postdated checks issued to members whenever the association was short of funds, and would replace the postdated checks with their own checks issued in the name of the members. PNB later on found out that some PEMSLA officers took out loans in the names of other members, without their knowledge or consent by forging the indorsement of the named payees in the checks. PNB then closed the current account of PEMSLA. The checks deposited to PEMSLA however, were debited from the Rodriguez account. Thus, spouses Rodriguez incurred losses. The spouses Rodriguez filed a civil complaint for damages against PEMSLA and PNB. They sought to recover the value of their checks that were deposited to the PEMSLA savings account amounting to P2,345,804.00. The spouses contended that PNB paid the wrong payees, hence, it should bear the loss. The RTC rendered judgment in favor of spouses Rodriguez, and ruled that PNB is liable to return the value of the checks. On appeal, the CA affirmed the RTC Decicion.. ISSUE: Whether the subject checks are payable to order or to bearer and who bears the loss. RULING: A check is “a bill of exchange drawn on a bank payable on demand.” It is either an order or a bearer instrument. As a rule, when the payee is fictitious or not intended to be the true recipient of the proceeds, the check is considered as a bearer instrument. Under Section 30 of the NIL, an order instrument requires an indorsement from the payee or holder before it may be validly negotiated. A bearer instrument, on the other hand, does not require an indorsement to be validly negotiated. It is negotiable by mere delivery. Under Section 9(c) of the NIL, a check payable to a specified payee may nevertheless be considered as a bearer instrument if it is payable to the order of a fictitious or non-existing person, and such fact is known to the person making it so payable. Thus, checks issued to “Prinsipe Abante” or “Si Malakas at si Maganda,” who are well-known characters in Philippine mythology, are bearer instruments because the named payees are fictitious and non-existent. For the fictitious-payee rule to be available as a defense, PNB must show that the makers did not intend for the named payees to be part of the transaction involving the checks. At most, the bank’s thesis shows that the payees did not have knowledge of the existence of the checks. This lack of knowledge on the part of the payees, however, was not tantamount to a lack of intention on the part of respondents-spouses that the payees would not receive the checks’ proceeds. Considering that respondents-spouses were transacting with PEMSLA and not the individual payees, it is understandable that they relied on the information given by the officers of PEMSLA that the payees would be receiving the checks. Verily, the subject checks are presumed order instruments. This is because, as found by both lower courts, PNB failed to present sufficient evidence to defeat the claim of respondents that the named payees were the intended recipients of the checks’ proceeds. The bank failed to satisfy a requisite condition of a fictitious-payee situation – that the maker of the check intended for the payee to have no interest in the transaction. Because of a failure to show that the payees were “fictitious” in its broader sense, the fictitious-payee rule does not apply. Thus, the checks are to be deemed payable to order. Consequently, the drawee bank bears the loss. PNB vs. Manila Oil Refining and By Products Company G.R. No. L-18103, June 8, 1922 FACTS: The manager and the treasurer of the defendant executed and delivered to the complainant Philippine National Bank a written instrument with a judgment note on demand, PNB brought an action and filed a motion confessing judgment. ISSUE: Whether or not a judgment note or a provision in a promissory note whereby in case the same is not paid at maturity, the maker authorizes any attorney to and confess judgment thereon for the principal amount with interest, costs and attorney’s fees, and waives all errors, rights to inquisition, and appeal, and all property exemptions. Will it affect the negotiable character of the instrument? RULING: No, a judgment note will not affect the negotiable character of the instrument. However, judgment note is not valid and effective. Warrants of attorney to confess judgment are void as against public policy because they enlarge the field for fraud, under these instruments the promissor bargains away his right a day in court, and the effect of instrument is to strike down the right of appeal accorded by statute. REPUBLIC PLANTERS BANK v. CA, GR No. 93073, 1992-12-21 Facts: This is an appeal by way of a Petition for Review on Certiorari from the decision* of the Court of Appeals in CA G.R. CV No. 07302, entitled "Republic Planters Bank, Plaintiff-Appellee vs. Pinch Manufacturing Corporation... which affirmed the decision** in Civil Case No. 82-5448 except that it completely absolved Fermin Canlas from liability under the promissory notes... and reduced the award for damages and attorney's fees. From the above decision only defendant Fermin Canlas appealed to the then Intermediate Appellate Court His contention was that inasmuch as he signed the promissory notes in his capacity as officer of the defunct Worldwide Garment Manufacturing,... Inc., he should not be held personally liable for such authorized corporate acts that he performed. It is now the contention of the petitioner Republic Planters Bank that having unconditionally signed the nine (9) promissory notes with Shozo Yamaguchi, jointly and severally,... defendant Fermin Canlas is solidarily liable with Shozo Yamaguchi on each of the nine notes. Defendant Yamaguchi and private respondent Fermin Canlas were President/Chief Operating Officer and Treasurer respectively, of Worldwide Garment Manufacturing, Inc. defendant Shozo Yamaguchi and private respondent Fermin Canlas were authorized to apply for credit facilities with the petitioner Republic Planters Bank in the forms of export advances and letters of credit/trust receipts accommodations. Petitioner bank issued nine promissory... notes In the promissory notes... the name Worldwide Garment Manufacturing, Inc. was apparently rubber stamped above the signatures of defendant and private respondent. Worldwide Garment Manufacturing, Inc. voted to change its corporate name to Pinch Manufacturing Corporation. petitioner bank filed a complaint for the recovery of sums of money covered among others, by the nine promissory notes with interest thereon, plus attorney's fees and penalty charges. Only private respondent Fermin Canlas filed an Amended Answer wherein he denied having issued the promissory notes in question since according to him, he was... not an officer of Pinch Manufacturing Corporation, but instead of Worldwide Garment Manufacturing, Inc., and that when he issued said promissory notes in behalf of Worldwide Garment Manufacturing, Inc., the same were in blank, the typewritten entries not appearing... therein prior to the time he affixed his signature. Issues: whether private respondent Fermin Canlas is solidarily liable with the other defendants, namely Pinch Manufacturing Corporation and Shozo Yamaguchi, on the nine promissory notes. Ruling: We find merit in this appeal. We hold that private respondent Fermin Canlas is solidarily liable on each of the promissory notes bearing his signature... t The promissory notes are negotiable instruments and must be governed by the Negotiable Instruments Law Under the Negotiable Instruments Law, persons who write their names on the face of promissory notes are makers and are liable as such. By signing the notes, the maker promises to pay to the order of the payee or any... holder[4] according to the tenor thereof.[5] Based on the above provisions of law, there is no denying that private respondent Fermin Canlas is one of the co-makers of the promissory... notes. As such, he cannot escape liability arising therefrom. Where an instrument containing the words "I promise to pay" is signed by two or more persons, they are deemed to be jointly and severally liable thereon. The fact that the singular pronoun is used indicates that the promise is individual as to each other; meaning that each of the co-signers is... deemed to have made an independent singular promise to pay the notes in full. In the case at bar, the solidary liability of private respondent Fermin Canlas is made clearer and certain, without reason for ambiguity, by the presence of the phrase "joint and several" as describing the unconditional promise to pay to the order of Republic Planters Bank. By making a joint and several promise to pay to the order of Republic Planters Bank, private respondent Fermin Canlas assumed the solidary liability of a debtor and the payee may choose to enforce the notes against him alone or jointly with Yamaguchi... and Pinch Manufacturing Corporation as solidary debtors. As to whether the interpolation of the phrase "and (in) his personal capacity" below the signatures of the makers in the notes will affect the liability of the makers... it is immaterial and... will not affect the liability of private respondent Fermin Canlas as a joint and several debtor of the notes. the respondent Court made a grave error in holding that an amendment in a corporation's Articles of Incorporation effecting a change of corporate name, in this case from Worldwide Garment Manufacturing, Inc. to Pinch Manufacturing Corporation, extinguished the... personality of the original corporation. A change in the corporate name does not make a new corporation, and whether effected by special act or under a general law, has no effect on the identity of the corporation, or on its property, rights, or liabilities Under the Negotiable Instruments Law, the liability of a person signing as an... agent is specifically provided for as follows: Sec. 20. Liability of a person signing as agent and so forth. Where the instrument contains or a person adds to his signature words indicating that he signs for or on behalf of a principal, or in a representative capacity, he is not liable on the instrument if... he was duly authorized; but the mere addition of words describing him as an agent, or as filling a representative character, without disclosing his principal, does not exempt him from personal liability. Where the agent signs his name but nowhere in the instrument has he disclosed the fact that he is acting in a representative capacity or the name of the third party for whom he might have acted as agent, the agent is personally liable to the holder of the instrument and... cannot be permitted to prove that he was merely acting as agent of another and parol or extrinsic evidence is not admissible to avoid the agent's personal liability. On the private respondent's contention that the promissory notes were delivered to him in blank for his signature, we rule otherwise. Such printed notes are incomplete because there are blank spaces to be filled up on material particulars An incomplete instrument which has been delivered to the borrower for his signature is governed by Section 14 of the Negotiable Instruments Law which provides, in so far as... relevant to this case, thus: Sec. 14. Blanks; when may be filled. -- Where the instrument is wanting in any material particular, the person in possession thereof has a prima facie authority to complete it by filling up the blanks therein. x x x x In order, however, that any such... instrument when completed may be enforced against any person who became a party thereto prior to its completion, it must be filled up strictly in accordance with the authority given and within a reasonable time. x x x x. We chose to believe the... bank's testimony that the notes were filled up before they were given to private respondent Fermin Canlas and defendant Shozo Yamaguchi for their signatures as joint and several promissors. For signing the notes above their typewritten names, they bound themselves as... unconditional makers. When the notes were given to private respondent Fermin Canlas for his signature, the notes were complete in the sense that the spaces for the material particular... had been filled up by the bank as per agreement. the private respondent Fermin Canlas is hereby held jointly and solidarily liable with defendants for the amounts found by the Court a quo. SPS. EDUARDO B. EVANGELISTA AND EPIFANIA C. EVANGELISTA v. MERCATOR FINANCE CORP., GR No. 148864, 2003-08-21 Facts: Petitioners, Spouses Evangelista... filed a complaint[1] for annulment of titles against respondents, Mercator Finance Corporation... and the Register of Deeds of Bulacan Petitioners claimed being the registered owners of... five (5) parcels of land[2] contained in the Real Estate Mortgage[3] executed by them and Embassy Farms, Inc. They alleged that they executed the Real Estate Mortgage in favor of Mercator Financing Corporation ("Mercator") only as officers of Embassy Farms. They did not receive the proceeds of the loan evidenced by a promissory note, as all of it went to Embassy Farms. Thus, they contended that the mortgage was without any consideration as to them since they did not personally obtain... any loan or credit accommodations. Mercator... contended that... plaintiffs executed a Mortgage in favor of defendant Mercator Finance Corporation `for and in consideration of certain loans, and/or other forms... of credit accommodations obtained from the Mortgagee (defendant Mercator Finance Corporation)... and to secure the payment of the same and those others that the MORTGAGEE may extend to the MORTGAGOR (plaintiffs)... then petitioners are jointly and severally liable with Embassy Farms. Due to their failure to pay the obligation, the... foreclosure and subsequent sale of the mortgaged properties are valid. Respondents Salazar and Lamecs asserted that they are innocent purchasers for value and in good faith,... The RTC granted the motion for summary judgment and dismissed the complaint. It held:... hat the liability of the signatories thereto are solidary in view of the phrase "jointly and severally."... petitioners went up to the Court of Appeals, but again were unsuccessful. The appellate court held: The appellants' insistence that the loans secured by the mortgage they executed were not personally theirs but those of Embassy Farms, Inc. is clearly selfserving and misplaced. The fact that they signed the subject promissory notes in the(ir) personal capacities... and as officers of the said debtor corporation is manifest on the very face of the said documents of indebtedness Issues: Whether or not the Real Estate Mortgage executed by the plaintiffs in favor of defendant Mercator Finance Corp. is null and void Whether or not the extra-judicial foreclosure proceedings undertaken on subject parcels of land to satisfy the indebtedness of Embassy Farms, Inc. is (sic) null and void; Whether or not the sale made by defendant Mercator Finance Corp. in favor of Lydia Salazar and that executed by the latter in favor of defendant Lamecs Realty and Development Corp. are null and void; Ruling: we affirm. Petitioners do not deny that they obtained a loan from Mercator. They merely claim that they got the loan as officers of Embassy Farms without intending to personally bind themselves or their property. However, a simple perusal of the promissory note and the continuing suretyship agreement shows otherwise. These documentary evidence prove that petitioners are solidary obligors with Embassy Farms. The promissory note[22] states: For value received, I/We jointly and severally promise to pay to the order of MERCATOR FINANCE CORPORATION The note was signed at the bottom by petitioners Eduardo B. Evangelista and Epifania C. Evangelista, and Embassy Farms, Inc. with the signature of Eduardo B. Evangelista below it. The Continuing Suretyship Agreement[23] also proves the solidary obligation of petitioners Courts can interpret a contract only if there is doubt in its letter.[25] But, an examination of the promissory note shows no such ambiguity. Besides, assuming arguendo that there is an ambiguity, Section 17 of the Negotiable Instruments Law states,... viz: SECTION 17. Construction where instrument is ambiguous. - Where the language of the instrument is ambiguous or there are omissions therein, the following rules of construction apply: (g) Where an instrument containing the word "I promise to pay" is signed by two or more persons, they are deemed to be jointly and severally liable thereon. Even if petitioners intended to sign the note merely as officers of Embassy Farms, still this does not erase the fact that they subsequently... executed a continuing suretyship agreement. A surety is one who is solidarily liable with the principal. Having executed the suretyship agreement, there can be no dispute on the personal liability of petitioners. Lastly, the parol evidence rule does not apply in this case. where the parties admitted the existence of the loans and the mortgage deeds and the fact of default on the due... repayments but raised the contention that they were misled by respondent bank to believe that the loans were long-term accommodations, then the parties could not be allowed to introduce evidence of conditions allegedly agreed upon by them other than those stipulated in the loan... documents because when they reduced their agreement in writing, it is presumed that they have made the writing the only repository and memorial of truth, and whatever is not found in the writing must be understood to have been waived and abandoned. IN VIEW WHEREOF, the petition is dismissed.