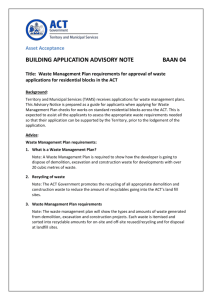

19734 Certificate IV CPC40110 Certificate IV in Building and Construction (Building) CPCCBC4002A Additional Resource 1 Copyright © State of New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013 Published by TAFE NSW Open Training and Education Network (OTEN) 51 Wentworth Rd Strathfield NSW 2135 Copyright of this material is reserved to the Crown in the right of the State of New South Wales. Reproduction or transmittal in whole, or in part, other than in accordance with provisions of the Copyright Act, is prohibited without the written authority of TAFE NSW Open Training and Education Network (OTEN). Disclaimer In compiling the information contained in and accessed through this resource, OTEN has used its best endeavours to ensure that the information is correct and current at the time of publication but takes no responsibility for any error, omission or defect therein. To the extent permitted by law, the Department of Education and Communities (DEC) and OTEN, its employees, agents and consultants exclude all liability for any loss or damage (including indirect, special or consequential loss or damage) arising from the use of, or reliance on the information contained herein, whether caused or not by any negligent act or omission. If any law prohibits the exclusion of such liability, DEC and OTEN limit their liability to the extent permitted by law, for the resupply of the information Third party sites This resource may contain links to third party websites and resources. Neither DEC nor OTEN is responsible for the condition or content of these sites or resources as they are not under the control of DEC or OTEN. This material has been cleared for use by TAFE NSW Open Training and Education Network (OTEN) for its enrolled students. Use by another organisation for any other purpose will need to be cleared and managed locally. Contents _Toc358903201 Disclaimer 5 Introduction 7 Demolition Work 8 Unrestricted demolition 8 Restricted demolition 8 Demolition work not requiring a licence 9 Demolition licences 9 Who is eligible to obtain a licence? 9 Public liability insurance details 10 What does appropriate qualifications mean? 10 Permits 10 Notifications 10 Demolition work 11 Excavation 12 To Support or Not to 12 Other Safety Aspects 14 Manual tasks 16 Methods for Manual Tasks 17 Mechanical Aids 19 Safe and Responsible Manual Handling 19 UV Exposure 20 UV Index and the SunSmart UV Alert 21 The different types of skin cancer? 21 Other damaging effects of the sun 22 Some common misconceptions about the sun 22 Noise Too much noise Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 23 25 3 Control measures 25 Summary 27 Extremes of Temperature Hot work and workplaces 28 Cold places 30 Compressed Air 32 Confined spaces 33 What are confined spaces? 33 What are the risks? 34 Fire extinguishers 35 Causes of fire 36 Poor housekeeping and storage 36 Human negligence 36 Improper use of equipment 37 Fire safety procedures 38 Fire extinguishers 38 Extinguishers 39 HAZCHEM procedures Material Safety Data sheets 4 28 43 44 Electrical/lighting 52 Bibliography 53 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Disclaimer Every effort has been made to provide correct information in this learning resource. However, the contents must not be relied upon to ensure compliance with health and safety legislation. To ensure you meet your compliance obligations under health and safety legislation you must be aware of the current health and safety Acts, Regulations, Codes of Practice and Guidelines currently operating in your State or Territory. Relevant and current documents can be found on the Regulator’s web page in your State or Territory as listed below: Australian Capital Territory: www.worksafety.act.gov.au/healthsafety New South Wales: www.workcover.nsw.gov.au Northern Territory: www.worksafe.nt.gov.au/home.aspx Queensland: www.deir.qld.gov.au/workplace/ South Australia: www.safework.sa.gov.au/ Tasmania: www.worksafe.tas.gov.au/home Victoria: www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/ Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 5 6 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Introduction When builders think of site safety they invariable focus on the potentially serious situations which can cause accidents with immediate implications. However, there are many more hazards on building sites and many with less serious consequences or which can produce long term effects like disease or chronic injury. The effects on health of say, bonded or friable asbestos have been known for many years, yet builders are still prepared to allow and direct workers to undertake dangerous demolition tasks because the effects on health are not immediate. • • • How many builders know how long you can safely operate certain power tools in a working day without adequate ear protection? What should we do before we send workers into a confined space? Should we allow an employee to be exposed to UV rays without adequate clothing for protection? These are all valid WHS issues which must be addressed by builders. Too often they are overlooked on site, particularly where there is not a safety management plan in use. To ensure you fulfil your obligation to your employees and provide a safe workplace, you need to become aware of what can cause harm and them take steps to ensure no one is at risk. For a start, you could ask yourself the following questions: • • • • Do you talk to your employees about safety and encourage them to work safely? Do you regularly inspect your sites to identify safety problems? Do you provide training in safety to your employees? Are you vigilant in maintaining plant and equipment used on your sites? The list is long which highlights the need to give safety some serious thought and to establish procedures to properly manage the issues. The topics covered in this unit will go some way towards providing you with a list of the on site hazards you will need to address as a builder. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 7 Demolition Work The WHS Act 2011 and WHS Regulation 2011 do not provide for the licencing of demolition work. Existing demolition arrangements will continue until demolition licensing under the National Occupational Licensing System commences, most likely in 2013 Under these transitional arrangements, demolition licence holders have an obligation to ensure that demolition work is performed in a manner that reduces the risk to the health of both demolition workers and the public. Demolition work must also only be carried out after Workcover has been notified. Unrestricted demolition Unrestricted demolition is a greater risk to health and, consequently, requires more stringent regulatory controls. It involves demolition of all types of buildings and structures including demolition: • • • • • • • • of structures greater than 15 metres in height of chemical installations – this includes any installation, equipment or vessel that contained dangerous goods or hazardous substances that have not been cleaned to an inert state of pre-tensioned or post-tensioned structures involving the use of tower cranes on site involving the use of mobile cranes with a rating capacity of more than 100 tonnes involving floor propping involving the use of explosives. Restricted demolition Restricted demolition includes the demolition of buildings or structures up to 15 metres in height and the mechanical demolition of buildings and structures above four metres in height and below 15 metres in height. Restricted demolition does not allow the use of tower cranes, mobile cranes with a rating capacity of more than 100 tonnes, or demolition involving chemical installations, pre-tensioned or post-tensioned structures, floor propping or the use of explosives. 8 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Demolition work not requiring a licence A licence is not required for the demolition by hand of any building or structure up to 10 metres in height or for the mechanical demolition of a building or structure less than four metres in height. Mechanical demolition refers to the direct use of mechanically-powered plant, such as excavators, bulldozers or cranes. Demolition licences There are two types of licences: • • DE1: Unrestricted Demolition Licence DE2: Restricted Demolition Licence Unrestricted demolition licence holders are also authorised to perform restricted demolition work so there is no need to obtain a restricted demolition licence if you already hold an unrestricted demolition licence. Who is eligible to obtain a licence? Applicants proposing to become licence holders must: • • • • • • • • be 18 years or above be a fit and proper person to hold a licence have appropriate demolition qualifications ensure that all employees have training in the work they are to carry out (restricted or unrestricted demolition) ensure that a nominated supervisor is on site at all times when licensed work is being carried out nominate an individual engaged in the management of the organisation with the appropriate qualifications in relation to demolition work (this person is called the management supervisor), and provide an ABN if they have one. What does fit and proper mean? To obtain, renew, maintain or hold a licence, an individual or corporation must fulfil the regulatory requirement of being ‘fit and proper’ under the OHS Regulation. The following matters will be considered in WorkCover’s assessment as to whether a person is fit and proper: • whether the person has been convicted of an offence under NSW occupational health and safety or other legislation administered by WorkCover Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 9 • • • • whether there is a record that the person has made a statement or provided information in connection with a WorkCover licence, permit or notification, knowing that the statement or information was false or misleading whether the person has failed to comply with the conditions of a conditional asbestos or demolition licence whether the person has been issued a significant number of notices pertaining to unsafe systems of work by a WorkCover inspector whether the person has had an asbestos or demolition licence cancelled or suspended by WorkCover. The period of assessment for ‘fit and proper’ will be two calendar years preceding the date of the licence application received by WorkCover. Public liability insurance details Demolition licence holders are required to have public liability insurance to cover the type of demolition work performed. What does appropriate qualifications mean? Appropriate qualifications generally refers to nominated supervisors and includes: • • • successful completion of WorkCover recognised courses in demolition work appropriate experience in demolition work the ability to demonstrate safe work Permits Before starting work, a site-specific permit approving the demolition of a building, or part of a building, that is more than four metres in height, or demolition involving pulling with ropes or chains or similar, must be obtained. A permit is also required if you intend to use explosives in demolition work. Notifications WorkCover must be notified before undertaking any demolition work where a licence is required. 10 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Demolition work Under the WHS Regulation 2011, demolition work is considered to be demolition or dismantling of a structure, or part of a structure that is loadbearing or otherwise related to the physical integrity of the structure, but does not include: (a) the dismantling of formwork, falsework, or other structures designed or used to provide support, access or containment during construction work, or (b) the removal of power, light or telecommunication poles. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 11 Excavation The recent collapse of a panel shop wall when the foundations were undermined during excavation reminds us of two lessons. The first is the dangers involved with excavation. The second is that if you don’t feel that an area is safe to work in, it probably isn’t. It was only luck that the wall collapsed early on a Saturday morning and there was no-one killed. The wall hit a gantry, which shifted and brought down power lines, leaving live wires hanging and the gantry itself was live for a time. With excavation work, water is nearly always present, either as a free liquid or as moisture within the soil itself. Soil itself varies in its nature. Some soils, like fine sand, flow comparatively freely, others, like stiff clay, are more cohesive. No soil, with or without moisture, can be relied on to support its own weight. It is for this reason that without support the sides of an excavation are likely to collapse over time. A cubic metre of soil weighs at least 1.35 tonnes. A fall of even a small amount can possibly kill a person. Excavation work, for these reasons alone, should never be treated casually. When earth or rock is removed, the newly excavated sides almost always need some form of temporary support or battering back. Assessment of possible causes of collapse and means of protection must take place long before digging starts. It is particularly useful to use the expertise of your excavator and also the geotechnical engineer To Support or Not to Adequate support depends on the type of soils the nature of the excavation, and whether ground water is present. It is difficult to know the best method to proceed with any excavation unless the soil condition is understood. The following points are important to remember in relation to the soil conditions and support that may be required during excavation: Stiff clays are cohesive and may stand vertically unsupported for a while. Wet sand will need substantial timbering or sheeting immediately. Cohesive soils can be deceptive and more accidents occur in these ‘better’ grounds through lack of proper support work than in all other types put together. 12 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Where trenches up to 4.5m deep are concerned, a general survey of the soil before excavation by trained competent personnel is needed to provide information for the selection of the most suitable support systems. Where larger excavations are concerned, or where usual support methods are not suitable, earth pressures should be considered, any support work should designed by an engineer with soils experience. Excavated sides in soft to firm clay will only remain unsupported to a shallow depth. Close sheeting or timbering is needed. Stiff Clay Stiff clay, stiff sandy or “gravely” clay will stand unsupported after excavation but for how long? This is an important question. The stability of the newly excavated face can deteriorate rapidly and the face of an excavation can collapse without warning. Often when a trench is excavated, soil at the sides can swell inwards due to pressure of the surrounding soil, causing cracks and the formation of unstable lumps that can break away, this often occurs more often during wet weather. Rock Rock would seem to be one of the most stable materials. In fact, all rock masses are separated into blocks by bedding planes. Bedding planes are lines of weakness within the rock: A bedding plane can sometimes contain water between them, or thin layers of clay which can act as a lubricant and on which sliding can take place when disturbance occurs. Where rocks are cut steeply the triangular mass of rock on the side towards the top is particularly unstable and has a high risk of sliding into the excavation. Timbering or sheeting with struts or anchor bolts is needed to hold such masses in place. In all rock excavations, loose and unstable material should always be removed. Small (but heavy) fragments may be held in place with adjacent fragments these can easily become dislodged. All such fragments should be removed. Any overhanging masses of rock should always be removed or pulled down. Water Water can get into excavations from rainfall or snow, as the after effects of frost, or because the excavation itself is below the ground water table. Water should always be considered a danger and continually monitored. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 13 Other Safety Aspects Access Safe access for getting into and out of any excavation must be provided at all times. In all cases ladders must be the correct type, length and designed for the use that they are being used. Ladders should be near the top to prevent slipping sideways. There must be handholds of 300mm-rail height at the upper level. Sufficient ladders to permit quick and easy escape in an emergency must be provided. One ladder every 15m is an industry average, the actual number should be assessed depending on the number of workers using the excavation. With extensive excavations, temporary access roads with edges that are signposted and marked clearly. Walkways should be provided in safely accessible areas when needed for access across excavations. Where falls of more than 1.8m into as excavation occur such walkways must be fitted with toe boards and guardrails and have a minimum clear width of 600mm. Specification requirements covering gangways across excavations should be checked. Barriers Where edges of excavations may cause a fall, it is wise to erect barriers, even near shallow trenches. They must be of sound construction and a minimum of 1m back from the edge of the trench. Maintenance All excavating work requires careful watching, even when support work has been installed, constant checking of safety equipment is critical. Small movements of earth are usually the only sign of weakening in cohesive soils, which can cause collapse. Such small movements can easily pass unnoticed but they are the signs that something needs to be done quickly or to get out. The working face must be inspected before every shift or at the minimum each day. Thorough examinations must be carried out once a week and be inspected immediately after any falls of earth. In dry conditions frequent watering of haul roads and working areas near the excavation may be required to reduce dust. During bad weather, spoil heaps need careful watching, they tend to slump and loose boulders or masonry and may fall back into a nearby excavation. 14 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Heavy vehicles should not be allowed near the edge of any excavations unless the support work has been specifically designed to permit it. It is wise to insist on the use of safety helmets and boots, not only during the actual excavation of hard material like rock, but also whenever workers are in positions where lumps of earth and other material can slide down or fall on them. Ventilation Excavations must be kept free from toxic or explosive gases. It must be remembered that excavations, being below ground, will naturally fill with all gases heavier than air. These gases may be natural, like methane and sulphur dioxide, or they may arise from nearby internal combustion engines (carbon monoxide), leakage from liquefied petroleum, gas equipment, leakage from underground storage or nearby oil piping, or sewer gases. Internal combustion engines must not be used in excavations with restricted ventilation when there are workers in the excavation. One of more commonly used and effective methods of prevention is to use special ventilation equipment to blow adequate clean air into the excavation and extract dirty air. Safety assessments and Safe Work Method Statements must always be carried out before work starts and as a continuing exercise throughout the period of the work. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 15 Manual tasks Manual tasks (previous known as manual handling) is the process where workers are required to move, lift, push, pull, carry, hold or force items including part of the work process by themselves or in groups. Work activities involving manual tasks are responsible for the largest amount of work based injury and long term injury or health problems, up to 100,000 cases of occupational back disorders are recorded every year. In 1990 Worksafe Australia produced the national standard for Manual handling and at the same time released the National Code of Practice for Manual Handling. That Code of Practice has now been replaced with the introduction of the Code of Practice for Hazardous Manual Tasks. The new Code provides practical guidance to persons conducting a business or undertaking on how to manage the risk of musculoskeletal disorders arising from hazardous manual tasks in the workplace. It applies to all types of work and all workplaces where manual tasks are carried out. A musculoskeletal disorder (MSD), as defined in the WHS Regulation 2011, means an injury to, or a disease of, the musculoskeletal system, whether occurring suddenly or over time. It does not include an injury caused by crushing, entrapment (such as fractures and dislocations) or cutting resulting from the mechanical operation of plant. MSD may include conditions such as: • • • • • • sprains and strains of muscles, ligaments and tendons back injuries, including damage to the muscles, tendons, ligaments, spinal discs, nerves, joints and bones joint and bone injuries or degeneration, including injuries to the shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip, knee, ankle, hands and feet nerve injuries or compression (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome) muscular and vascular disorders as a result of hand MSDs occur in two ways: • • 16 gradual wear and tear to joints, ligaments, muscles and inter-vertebral discs caused by repeated or continuous use of the same body parts, including static positions. sudden damage caused by strenuous activity, or unexpected movements, such as when loads being handled move or change position suddenly. Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 A hazardous manual task as defined by WHS Regulation 2011 means a task that requires a person to lift, lower, push, pull, carry or otherwise move, hold or restrain any person, animal or thing involving one or more of the following: • • • • • • repetitive or sustained force high or sudden force repetitive movement sustained or awkward posture exposure to vibration A complete guide on the characteristics of hazardous manual tasks and PCBU’s responsibilities to control associated risks is provided in the Code of Practice Hazardous Manual Tasks. www.workcover.nsw.gov.au Methods for Manual Tasks Lifting Correct lilting methods require you to bend you, knees, not your back. Never twist your body when lifting, carrying or moving a load. Protect your hands and feet with suitable PPE. Size up the load. Consider the shape and size of the load, and the weight. If the load appears too heavy get assistance. Position the feet. Face the Intended direction of travel. Place your feat comfortably span, one foot forward of the other and as close as possible to the object to be lifted. Obtain a proper hold. Get a safe, secure grip, diagonally opposite the object, with the whole length of the fingers and part of the palms or your hands. Maintain bent knee, Straight back. The knees should be bent before the hands are lowered to lift or set down a load. Keep the upper part of your body erect and as straight as possible. Keep tire head erect, chin in. Keep the head erect and chin in to help keep the back straight Take a deep breath and begin to raise the Load by straightening your legs Complete the lift with your back held straight. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 17 Keep your arms in. Keep your arms close to the body and your elbows and knees slightly bent. Hold the load in close to your body. Maintain flexible control over the load with your arm and leg muscles. Lowering Setting down the load is the reverse of lifting. It is just as essential to keep the back straight and bend the knees while lowering the Load as when lifting it. Dual lifting When more than one person is required to lift and carry a loud, the correct lifting methods must be practised, and coordinated team lifting techniques should he applied. Coordinating team, lifting One person only should give the orders and signals, and this person should he able to see what is happening. The movements of the team members should be performed simultaneously (all lift together). All persons Involved in the lift should be able to see or hear the one giving the orders. To enable load sharing. Lifting partners should be of similar height and build, or lifters should be graded by height along the load. Persons should be adequately trained in team lifting and preferably have been trained together. Pushing and pulling Tasks requiring the pushing or pulling of loads are more effectively carried out if the force is applied at or around waist level. When setting the load in motion, jerky actions should be avoided. Apply the force gradually to avoid overexertion and damage to the body 18 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Mechanical Aids Mechanical aids help to reduce the amount of manual handling and the effort used for lifting and carrying tasks that occur in the work environment. The following list identifies a number of ways or items that can be used to reduce the manual handling that occurs in the construction industry. • • • • • • • Crowbars and Levers Rollers Wheelbarrows Hand Trucks, trolleys and wheelsets Cranes and hoistsjacks and lifting tackle Forklift and pallet jacks Lifting Grips Safe and Responsible Manual Handling There are a number of checks that can be carried out prior to lifting or moving an item to ensure that the manual handling that is about to be undertaken is being done in a safe manner. The following is a list of things that can be checked during a manual handling exercise: • • • • • • • • • Walk in an upright position. Do no carry a heavy load under one arm. Before moving a load check the route to be travelled. Remove trip obstacles and confirm locations of overhead obstacles. Check the location that the object is to go to so as to ensure there is space. If supports are to be used to help carry the load check that they are sufficient. Hazardous materials should be handled with the appropriate care. When changing direction during a lift ensure that the feet are used and the whole body turns as one. Avoid manual handling in tight cramped spaces. When carrying individual items ensure the body is evenly balanced by splitting the loads between each arm. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 19 UV Exposure Australian has the highest rate of skin cancer in the world. One in two people living in Australia will develop skin cancer during their lifetime. Australia's skin cancer rates are high because Australia experiences some of the highest levels of UV radiation in the world. Even on cool or cloudy days, UV radiation can be strong enough to damage skin. UV radiation is electromagnetic energy. UV radiation is of concern to workers in the construction industry due to the amount of work and length of time spent outdoors. The most common source of UV radiation is the sun, but there are other sources in the workplace including lasers, welding flashes and high intensity lighting. Here we will focus on UV radiation from the sun. Some of the control measures include: • • • • • • • • • 20 change the job so that much of the work is carried out indoors or in a location away from direct sunlight, work in shade using natural or existing shade from trees, surrounding buildings or structures, install awnings, canopies/sails, tents or umbrellas to protect workers, rotate workers, change work times to avoid exposure to sunlight during the hottest times of the day, use appropriate PPE: Slip on some sun-protective work clothing. Cover as much skin as possible. Long pants and work shirts with a collar and long sleeves are best. Choose lightweight, lightly coloured material with a UPF 50+ rating. Choose loose fitting clothing to keep cool in the heat. Slap on a hat. A hat should shade your face, ears and neck. A broad brimmed styled hat should have at least a 7.5 cm brim. A bucket style hat should have a deep crown, angled brim of 6 cm and sit low on the head. Legionnaire style hats should have a flap that covers the neck and joins to the sides of the front peak. If wearing a hardhat or helmet use a brim attachment or use a legionnaire cover. Slop on SPF30+ sunscreen. No sunscreen provides complete protection so never rely on sunscreen alone. Choose sunscreen that is broad spectrum and water resistant. Apply sunscreen generously to clean, dry skin 20 minutes before you go outdoors. Protect your lips with a SPF 30+ lip balm. Always check and follow the use by date on sunscreen. Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 • Slide on some sunglasses. Be aware that your eyes can also be damaged by the sun's UV radiation. Wear close fitting, wrap around style sunglasses. When buying new sunglasses, check the swing tag to ensure they meet the Australian Standard (AS 1067:2003 - category 2, 3 or 4) and are safe for driving. Look for an EPF (eye protection factor) of 10. Safety glasses that meet AS/NZS 1337 still provide sun protection. Polarised lenses reduce glare and make it easier to see on sunny days. Remember to use these steps together for the best protection. UV Index and the SunSmart UV Alert UV radiation levels vary in strength across Australia on any given day. The UV Index is a rating system for the amount of UV radiation present in sunlight. The higher the number, the stronger the levels of UV radiation and the less time it takes for skin damage to occur. When the UV Index is at 3 and above, the level of UV radiation in sunlight is strong enough to damage the skin. The Bureau of Meteorology issues the SunSmart UV Alert whenever the UV Index is forecast to reach 3 and above. The SunSmart UV Alert appears on the weather page of all Australian daily newspapers and is available on the Bureau of Meteorology website. Go to www.bom.gov.au and do a search for "UV Alert". The time period displayed in the SunSmart UV Alert tells you when to use sun protection while working outdoors. And remember, extra care should be taken between 10.00 am to 3.00 pm when UV Index levels reach their peak. The different types of skin cancer? The three main types of skin cancer are: • • • basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and melanoma. BCCs and SCCs are the most common skin cancers and melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer. Outdoor workers are more likely to develop the common skin cancers on sunexposed areas such as the head, neck, ears, lips, shoulders, legs and arms. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 21 Other damaging effects of the sun In addition to skin cancer, prolonged and repeated sun exposure can result in the following: • • • • • • • skin damage sunburn (permanent damage can occur after 2 hours) keratoses or sunspots premature ageing wrinkles skin pigmentation and discolouration lip cancer Eye injuries and diseases • • • • inflammation and irritation cataracts - cloudiness of the eye lens pterygium (tur-rig-ium) an overgrowth of the white conjunctiva onto the cornea cancer of the eye and of the skin surrounding the eyes. Some common misconceptions about the sun Windburn There is no such thing as windburn. The wind may dry the skin but cannot burn it. What is described as windburn is actually sunburn. High levels of UV radiation only occur on hot days Heat or high temperatures are not related to levels of UV radiation. Temperature relates to the amount of infrared radiation (not UV radiation) present in sunlight. We cannot feel or see UV radiation, so don't incorrectly use temperature as a guide to when sun protection is needed. 22 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Noise Not all sound is noise — noise is sound that people do not like. Noise can be annoying and it can interfere with your ability to work by causing stress and disturbing your concentration. Noise can cause accidents by interfering with communication and warning signals. Noise can cause chronic health problems. Noise can also cause you to lose your hearing. Hearing loss from exposure to noise in the workplace is one of the most common of all industrial diseases. Workers can be exposed to high noise levels in workplaces as varied as construction industries, foundries and textile industries. Short-term exposure to excessive (too much) noise can cause temporary hearing loss, lasting from a few seconds to a few days. Exposure to noise over a long period of time can cause permanent hearing loss. Hearing loss that occurs over time is not always easy to recognize and unfortunately, most workers do not realize they are going deaf until their hearing is permanently damaged. Industrial noise exposure can be controlled — often for minimal costs and without technical difficulty. The goal in controlling industrial noise is to eliminate or reduce the noise at the source producing it. Noise is a significant occupational health and safety issue in the construction industry. Noise on and near construction sites is usually associated with: • • • vehicles and traffic, machinery and heavy equipment hand and explosive powered tools. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 23 If noise is too loud it can permanently damage our hearing. The danger largely depends on the level of noise and how long you are exposed to it. The damage is generally gradual and goes unnoticed for some time. Some examples of approximate noise levels (dB): • • • • • • 24 normal conversation 60 heavy traffic 80–90 riveting hammer 90–100 heavy-duty wood saw 95–105 angle grinder 100–105 router 105 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Too much noise So how much noise is too much in the workplace? How long can workers be exposed to loud noise? A workplace is described as unsafe and at risk to health, if people are exposed to noise levels exceeding an eight hour noise equivalent of 85 dB(A) or peak at more than 140dB(C). The following table goes some way to answering these questions although the level of noise on a building site is not always known. dBA Allowable length of exposure 85 8 hours 88 4 hours 91 2 hours 94 1 hour 97 30 minutes 100 15 minutes 103 7 minutes 106 4 minutes 110 1 minute For example, a worker using an angle grinder could be exposed to a noise level of 110dB and therefore could only have unprotected exposure of 1 minute. Control measures Some control measures include: • • • • • • • • purchase new tools which operate quieter minor design changes to plant regular plant maintenance isolate or enclose the noisy parts of the plant use sound absorption devices/substances (e.g. sound proof booths, noise barriers or partitions) reduce metal to metal impact or suppress vibrating surfaces use of safety signs to alert people to noisy areas use of PPE such as ear plugs or muffs adequate training and information. Clause 49 of the OHS Regulation states that an employer must ensure that appropriate risk control measures are taken when noise levels: • • exceed an eight hour noise level equivalent of 85 dB(A); or peak at more than 140 dB( C). Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 25 Employers are required to determine whether noise levels in the workplace exceed the exposure limits specified in the Regulation and, if noise levels do exceed these limits, implement noise management systems to eliminate the noise hazard or reduce exposure to acceptable levels. If noise cannot be eliminated the employer must take the following measures (in the order specified) to minimise the risk to the lowest level reasonably practical: • • • • • substitute the hazard isolate the hazard from the person minimise the hazard using engineering means minimise the hazard using administrative means use personal protective equipment. A combination of the above measures may be necessary to minimise the risk to the lowest possible level if a single measure is not sufficient for that purpose. Generally speaking, adequate noise management can be achieved by implementing some of the following: • • • treating the noise at its source, or its transmission path (e.g. substituting with a quieter machine, isolating by way of sound barriers or distance, engineering by use of sound dampeners on the equipment); administrative noise control measures (e.g. training and education, job rotation, job redesign or rosters designed so that as few employees as possible are exposed to noisy operations at any one time and for reduced durations); personal hearing protectors (e.g. ear muffs, ear plugs) In practice the most effective strategy may be provided by a combination of controls. Just remember the following points when you are experiencing noise in your vicinity. Occupational hearing loss is one of the most common of all industrial diseases. Not all sound is noise — noise is unwanted or unpleasant sound. Noise can cause stress and interfere with concentration. It can cause chronic health problems and it can also cause accidents by interfering with communication and warning signals. Short-term exposure to excessive noise can cause temporary hearing loss. Exposure to noise over a longer period of time can cause permanent hearing loss. 26 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Summary Temporary or permanent hearing loss from occupational noise exposure is one of the most common of all industrial diseases. Occupational noise exposure can cause a number of chronic health problems in addition to hearing loss. However, noise can be controlled by a variety of methods, the most effective of which is controlling noise at the source; the least acceptable method is relying on ear protection. Where there is a risk to health and safety from exposure to noise due regard must be given to the Code of Practice: managing noise and preventing hearing loss at work. (WorkCover NSW web page - www.workcover.nsw.gov.au) Below is a checklist that can be used as a guide for assessing noise exposure in a work environment. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 27 Extremes of Temperature Hot work and workplaces In Australia hot work and hot workplaces are common, especially in summer. They are any set of conditions which create heat stress in employees. The heat can be from hot work processes, hot climatic conditions, heavy work in moderately hot conditions and work where occlusive clothing must be worn. Factors which contribute to heat stress are those which produce heat and/or affect the body’s ability to disperse excess heat and maintain normal body temperature. They include: • • • • • Work rate: the heavier the work, the greater the amount of metabolic heat which has to be dissipated Air temperature: the higher the air temperature, the harder it is for the body to dissipate heat and maintain body temperature Humidity: the higher the humidity the lower the sweat evaporation rate. Since the body’s main mechanism for dispersing heat is through evaporation of sweat, this reduces the body’s ability to cool itself Air flow: the higher the rate of air flow (or wind speed) the greater the area of evaporation of sweat from the skin Clothing: Occlusive clothing (very heavy clothing or impervious full body suits such as are worn for protection in very hazardous conditions) reduces heat dispersion by trapping the heat within the clothing. With no airflow against the skin to evaporate sweat, heat dispersion is prevented. To remain healthy, the human body must maintain its temperature within a narrow range centred around 37 degrees Celsius. Death can occur if the body temperature falls much below 27 degrees Celsius or rises much above 42 degrees Celsius. Ill health due to heat stress The health effects of heat stress include: • • • 28 Mild heat illness: those affected fell weak, dizzy or generally unwell Heat syncope (fainting): this occurs when employees stand still in one place in heat. Blood tends to pool in the legs and the person then faints. Heat exhaustion: heat exhaustion causes collapse of the affected person due to dehydration, salt loss and/or an overloaded cardiovascular system. Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 • • • • Heat stroke: is a very serious condition since death or permanent injury from brain damage can result. Signs of heat stroke include: irritability, confusion and disorientation, incoherent speech, convulsions, loss of consciousness, body temperature exceeding 42 degrees Celsius and cardiac arrest. Salt deficiency: symptoms include lethargy, weakness, and muscular cramps Prickly heat: this is a widespread red rash which feels itchy. Psychological effects: overexposure to heat and the resulting dehydration can trigger psychological effects. These include irritability, decreased efficiency and decreased mental function. Personal risk factors There are a number of personal risk factors which affect the susceptibility of employees to heat stress which all employees and supervisors should be aware of. These include: • • • • • • • Age Health status Weight Fitness Diet Medication Pregnancy Factors to protect workers from heat-induced injuries Acclimatisation: allow workers to adapt to the hot conditions. The body will usually adapt in about one week. Workers should commence work at a reduced rate and increase their load over the next week. Drinking cool non-alcoholic drinks at frequent intervals: it is most important that workers take frequent cool drinks to avoid dehydration. Attend medical checkups: employees who work continuously in hot environments should have a regular medical examination to assess their fitness for hot work. Take regular rest breaks: regular rest breaks allow the body a chance to cool down by temporarily reducing metabolic heat output and by moving to a cooler part of the workplace. Wearing appropriate clothing: choice of clothing makes a big difference to the body’s ability to dissipate heat through evaporation and heat transfer. Report any symptoms of ill health immediately: employees feeling any of the symptoms associated with mild heat stress should inform their supervisor immediately. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 29 Information and training Since the consequences of heat-induced illness can be so severe as to cause death, it is particularly important that employees and their supervisors be trained in the different types of heat-induced illnesses and their symptoms and the ways in which they can be managed in the workplace. Cold places Cold workplaces are not as significant an issue in Australia, with our relatively warm climate, as they are in other parts of the world. However they are still an issue for outdoor workers in some parts of the country and in some industries. Cold workplaces are difficult to define since there is more than one factor involved in the amount of chill experienced. The three main factors affecting heat loss from the body leading to cold injuries are: • • • Temperature Wind (air) speed Moisture The lower the temperature and the greater the wind speed, the greater the risk is. If employees are wet, especially if they are immersed in water, loss of heat is accelerated dramatically. The risk of whole body chilling (hypothermia) does not generally occur above 10 degrees Celsius. However, in very cold winds, it can occur in temperatures as high as 18 degrees Celsius. Localised effects such as frostbite require temperatures below freezing point. Cold workplaces in Australia will generally be associated with the following: • • • • • Outdoor workers in winter Refrigerated warehouses Alpine regions Frozen food industry Divers and fisherman Ill health due to cold Hypothermia: this is a generalised cooling of the whole body due to exposure to intense cold as the body is unable to compensate for heat loss. Symptoms include the feeling of cold and pain. When the body temperature drops to about 27 degrees Celsius, coma sets in and death can follow soon after. Victims should be treated immediately by warming. Frostbite: is a localised effect which occurs when tissue of the extremities (hands, feet, face, ears) actually freeze. Frostbite can be superficial, affecting the skin, or it can be deep, affecting muscle, nerves, tendons and blood vessels. Frostbite injuries can take many months to heal. Chilblains: these are painful, inflamed swellings or sores which can occur on the hands or feet from exposure to cold. 30 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Frostnip: skin on the extremities or face (fingers, toes, ears and nose) can turn white, particularly when exposed to cold winds Aggravation of existing medical conditions: some medical conditions are aggravated by very cold conditions including bronchitis, asthma and blood circulation issues. Safety: in cold working conditions, safety can be compromised because cold can severely affect the sense of touch and manual dexterity. Personal factors affecting those working in cold conditions are generally the same for those working in hot environments. Management of workers in cold conditions should include, rest breaks with warm drinks and the wearing of adequate clothing. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 31 Compressed Air Many site operations, tools and equipment used compressed air for power or for cleaning down. Compressed air can also injure or kill. The majority of fatalities associated with the wrong uses of compressed air are attributed to sky-larking and horseplay, however many people have been seriously injured and some killed by inappropriate use. Air under pressure can be just as dangerous as high pressure steam and when released suddenly can cause serious injury. It can maim, tear or embed material into the skin and bones of the human body. Air played around the face can blow out an eye, or if directed at an ear, it may puncture an ear drum and cause deafness. A person who has been painting or covered with dirt or soot can have poisonous particles blasted into the body where they immediately combine with the blood. Even air without impurities is dangerous when forced into the bloodstream through a cut or pores in the skin. Clothing is little protection against compressed air. Workers using compressed air should regularly be reminded of the following points: • • • • • • • • • • Do not play practical jokes with compressed air – it can be fatal Never use compressed air to clean clothing, hair or the body Never point the hose at anyone and always ensure other workers are not in the line of the air flow. Always ensure hoses and tools are good working order Do not leave air on when not in use. Always wear personal protection equipment such as glasses and face shields. Air hoses should be securely held to prevent whipping. Compressed air contains contaminants which make it unsuitable for respiratory purposes. Tools used in conjunction with compressed air can injure or kill if used inappropriately. Regularly check air compressors for faults and ensure all guards are securely in place. Compressed air deserves to be treated carefully and must be a consideration in any risk assessment at the workplace. 32 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Confined spaces What are confined spaces? Confined spaces are spaces that have limited or restricted means of entry and exit, and may contain harmful atmospheres or stored substances that pose a risk to employees working in them. A ‘confined space”, according to the WHS Regulation 2011, means an enclosed or partially enclosed space that: (a) is not designed or intended primarily to be occupied by a person, and (b) is, or is designed or intended to be, at normal atmospheric pressure while any person is in the space, and (c) is or is likely to be a risk to health and safety from: (i) an atmosphere that does not have a safe oxygen level, or (ii) contaminants, including airborne gases, vapours and dusts, that may cause injury from fire or explosion, or (iii) harmful concentrations of any airborne contaminants, or (iv) engulfment, but does not include a mine shaft or the workings of a mine. Examples of confined spaces include: • • • • • • • • • • storage tanks, tank cars, process vessels, boilers, pressure vessels, silos and other tank- like compartments, open-topped spaces such as pits or degreasers, pipes, sewers, shafts, ducts and similar structures, shipboard spaces entered through a small hatchway or access point, cargo tanks, cellular double bottom tanks, duct keels, ballast and oil tanks and void spaces (but not including dry cargo holds), vats, tanks and silos, pipes and ducts, ovens, chimneys and flues, sub floors and roof spaces, underground sewers or wells, and shafts, trenches, tunnels and pits. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 33 What are the risks? Working a confined spaces car’ be extremely dangerous. Some of the risks include: • • • • • Loss of consciousness, injury or death due :o contaminants in the air. Fire or explosion from the ignition of flammable contaminants. Suffocation caused by a lack of oxygen. Enhanced combustibility and spontaneous combustion. Suffocation or crushing after being engulfed by loose materials stored in the space, such as sand, grain, fertiliser, coal or woodchips. It is not uncommon for incidents involving confined spaces to often result in multiple fatalities other workers, unaware of the risks, often enter a space to rescue a victim but are then also overcome by toxic vapours or gases. Persons must not enter or work in or on a confined space unless authorised by an entry permit issued by Management. All work must comply with the WHS Regulation 2011 (Chapter 4, Part 4.3 Division 3 - Confined Spaces). * Please Note: ‘safe oxygen level’ means a minimum oxygen content in air of 19.5% by volume under normal atmospheric pressure and a maximum oxygen content in air of 23.5% by volume under normal atmospheric pressure. WorkCover legislation requires fully trained operators to enter a confined space and at no times is an unlicensed person to enter a confined space. Where a PCBU requires work to be carried out in a confined space due regard must be given to the Code of Practice: Confined spaces (WorkCover NSW web page - www.workcover.nsw.gov.au) 34 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Fire extinguishers The following deals with procedures which can be implemented to ensure the requirements of OH&S legislation in regard to fire safety are met on residential building sites. Potential causes of fire on a site and the likely danger spots will be identified. We will distinguish between the different classes of fire, and then describe the appropriate types of fire extinguishers to be used in each case. To conclude the chapter we will deal with standard HAZCHEM procedures required by law. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 35 Causes of fire There are a number of potential causes of fire on a construction site. They are human negligence, poor housekeeping and storage and improper use of materials and equipment. Management needs to incorporate fire planning and control particularly through the training of personnel to avoid fires being caused. Poor housekeeping and storage Housekeeping refers to keeping materials and equipment on site, in order. A lack of good housekeeping can result in combustible materials being left to accumulate on a project creating a fire hazard. Rubbish on a building site should be cleared away daily. Dangerous activities such as welding and grinding, that could ignite material, should occur away from highly flammable material Human negligence Human negligence and carelessness can result in non-extinguished cigarettes being thrown into the combustible material. For the most part smoking is not allowed on building sites except in designated smoking areas where ash trays are provided for the extinguishment of cigarettes. Butane cigarette lighters could be a source of ignition so owners should be aware of where they leave them. Some work practices on building sites require the use of toxic or poisonous and flammable substances. For instance, floor-covering installers and painters use some adhesives, sealers and cleaning agents that are toxic and or flammable. Handling and storage of these substances must be in accordance with Australian Standard AS 2508. Generally all flammable liquids should be stored correctly away from any sources of ignition. Rags soaked with oil, paint or solvent are potentially dangerous. They should be put in a metal container fitted with automatic lids, and emptied at the end of each shift. Sawdust should never be used to catch oil drippings because of the flammable nature of both. Corrosive chemicals should be stored in a container appropriate for that particular chemical and not stored in traffic areas or near electrical equipment because they could strip electrical wire. 36 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Improper use of equipment Equipment, materials and plant should be inspected regularly for safety purposes, and procedures for safe use should be followed. Equipment and plant should be inspected regularly for signs of wear and potential danger Qualified personnel should maintain electrical equipment and check for overloading of electrical circuits and wiring. Dangerous situations such as perished rubber hoses on gas bottles and electrical malfunctions in motors or generators should be identified. Electrical leads should be inspected and tagged on a regular basis. Electrical equipment should be turned off and unplugged when not in use. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 37 Fire safety procedures The size of the building site will influence the types of fire safety procedures that are put into place on a building site. The head contractor is responsible for setting up fire safety procedures on a building site. These are likely to be part of a coordinated approach to site safety. They may be part of a hazard assessment and risk control program. A regular safety audit conducted by the site supervisor should monitor all equipment, plant and materials on site for suitability of storage and safe conditions. As well personnel should be monitored in their use of equipment to ensure safe procedures are being adhered to. Fire extinguishers All sites should have the appropriate fire extinguishers readily available. The appropriate fire extinguisher is determined by the type of fire. There are six classes of fire and five general types of fire extinguisher. We will now look at each in turn. Class A fires These are fires involving solid materials, normally made up of carbon compounds. They are usually fires involving wood, paper, plastics and fibre. Class B fires These are fires involving liquids or liquefiable solids. Examples of liquids that are combustible include: petrol, oil, acetone, ethanol, paraffin and paints. The following are examples of liquefiable solids and include plastics such as polystyrene, polypropylene and polyethylene. The above class of fire may be further divided into two groups based on the appropriate extinguishing agents. The two sub-categories are: the flammable liquids and liquefiable solids that are miscible i.e. they mix with water, and the flammable liquids and liquefiable solids that are immiscible they won’t mix with water. Class C fires These are fires where the fuel element is a gas or liquefied gases, such as methane, propane and butane. Class D fires These are fires where the fuel is a metal, such as magnesium, sodium, potassium, zinc dust, iron filings, aluminium dust and titanium dust. 38 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Electrical fires Although there is no class specifically for electrical fires, since electricity itself does not burn, they are sometimes referred to as ‘Class E’ fires. In reality they can be classified as A, B or D, but because they may involve all three types, they are often considered separately. Class F fires These are fires where the fuel is in the form of cooking oils or fats. Extinguishers There are a number of different extinguishers available with different extinguishing agents inside them that are used to fight the different types of fires discussed above. Water-based extinguishers Water-based extinguishers should only be used on Class A type fires; that is fires involving the burning of solid materials such as wood, paper or fibre. If water is applied to Class B fires (flammable liquids), it simply spreads the problem. The water does not mix with the fuel, which floats on top of the water and continues to burn. It also has little effect on burning gases. Warning! Adding water to burning metals, or electrical fires, can be particularly hazardous, leading to possible explosions. This type of extinguisher should not be used on electrical fires as it may cause electrocution. Insert RSS 1 - figure 2.1 Fire Science B Figure 4.1. A diagram of a water-based extinguisher. Foam extinguishers The foam type of extinguisher should be used on Class B fires. Where soluble alcohols such as methanol and ethanol are involved, the alcohol-based foam is used. Foam extinguishers are ineffective against flammable gases and should not be used on burning metals as they also make the fire worse. Foam is not effective on flammable liquids escaping under pressure as this may cause the foam blanket to break up. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 39 Warning! This type of extinguisher should not be used on electrical fires as it may cause electrocution. Carbon dioxide extinguishers Because carbon dioxide acts as a smothering agent, it can be used on any type of fire except for those that supply their own oxygen and for burning metal fires. If carbon dioxide extinguishers are used on burning metal fires, there is the possibility that the metal might cause the carbon dioxide to dissociate, releasing the oxygen and thus the metal burns more quickly using the liberated oxygen. There are some other disadvantages of using carbon dioxide as an extinguishing agent. The extinguishment has a relatively short range. The discharge horn becomes very cold due to the low temperature of the fluid expanding to a gas. Carbon dioxide can be affected by wind or draught and it can also cause people to faint through lack of oxygen in confined spaces. If used on Class A fires, water should be used as a follow up to prevent reignition. If used on electrical fires, the equipment should be disconnected as soon as possible to prevent re-ignition. The attached link shows the correct way to use a Carbon dioxide extinguisher: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W_jgJzb8IxM Warning! Class C fires (flammable gas) should not be extinguished unless the source of the gas can be turned off! When the fire is extinguished and the gas continues to escape there is potential for explosion. Insert RSS 3 figure 2.3 Fire Science B Figure 4.3. A diagram of a carbon dioxide extinguisher. Dry chemical extinguishers Dry chemical powders are most effective against flammable liquids. They can be used on all types of fires except for burning metals. Special dry chemicals have been developed especially for burning metals. Dry chemicals extinguish fires by free radical quenching. As such they provide little cooling so it is necessary to follow up with water or foam. As with carbon dioxide types, if used on electrical fires, the equipment should be disconnected as soon as possible to prevent re-ignition. Dry chemical residue should also be removed as soon as possible after the fire has been put out. Insert RSS 4figure 2.4 Fire Science B Figure 4.4. A diagram of a dry chemical extinguisher. 40 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Dry chemicals and metal fires Special powders have been developed for metal fires. These extinguish by the physical process of starvation or the limitation of fuel. Either a crust is formed over the burning surface of the fuel, or the powder melts and runs as a flux over the surface. One powder known as the ternary eutectic chloride group was researched, perfected and developed, by the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority. The name ternary eutectic indicates that three salts are used in this Class D powder, and that the melting point, lower than any of the individual melting points, is the lowest that can be obtained with these three salts. The mixture comprises potassium, barium and sodium chlorides, but there is a more effective (though more expensive) mixture containing lithium chloride instead of sodium chloride. Extinguishers suitable for use on combustible metals are orange. See the following Link for more information about Dry Chemical/ powder extinguishers http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wahXwItLRY Warning! The barium chloride is poisonous, so care must be taken when handling this powder. Types of fires for wet chemical extinguishers Wet chemical extinguishers are ideal for fires involving cooking oils and fats as they were initially developed especially for this purpose. They may also be used for fires involving ordinary solid materials such as wood, paper and plastics. Warning! This type of extinguisher should not be used on electrical fires as it may cause electrocution. Halon extinguishers Halon extinguishers may still be used from time to time, where a special exemption permit has been granted. The agent leaves no residue and is at least twice as effective on Class B fires as carbon dioxide when compared on a weight for agent basis. It also has about twice the range. Usually a boost of nitrogen is added to ensure proper operation of the pressurised contents of the cylinder. Halon agents are also less affected by wind and air currents than carbon dioxide. Their main disadvantage is that they create environmental problems by depleting the ozone layer in the upper atmosphere and it is for this reason that they have been banned. Insert RSS 5 - figure 2.5 Fire Science B Figure 4.5. A diagram of a halon extinguisher. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 41 Activity 1 Contact your local fire service and determine where personnel may be trained in the use of fire extinguishers. Also you can look at some of the videos on the OTEN Maritime Youtube page or on the link below whilst this is not training it does give some pointers that you may find useful and could use in the event that you may need to fight a fire with an extinguisher. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oM-yjvraxf8 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3G0a-MLneRs Activity 2 Read through the Fire Extinguisher Chart so that you are able to understand the various types of extinguishers and on what types of fires they should be used. 42 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 HAZCHEM procedures The amount of toxic or flammable substances used on residential building sites is generally small and they are usually on site for a very short time. Therefore the strict regulations governing manufacturing industries are difficult to enforce on a building site. HAZCHEM is the sign that indicates hazardous chemicals are present on a site. When hazardous chemicals are present warning notices must be displayed such as the ones shown in the figures below. These have instructions about emergency procedures regarding spills, leaks, fire and first aid. Types of Hazchem signs It is important that all building workers learn to recognise and understand the warning notices, such as those shown in Figure 4.7, and safety signs that may be used on site. Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 43 Figure 4.7. Some major hazard symbols. Material Safety Data sheets Any chemicals delivered to a building site will come with a Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS). This will provide all the relevant safety information on the chemical substance. Much of the information contained in an MSDS is provided by the supplier/manufacturer of the particular chemical. All chemicals should be supplied with an MSDS. This will at least show a list of ingredients and safety information. The type of information you would expect to find in an MSDS would include health hazard information, precautions for use, first aid procedures, safe handling procedures and physical/chemical properties The pages that follow are examples of MSDS that have been searched for on the internet. The MSDS also contain an action guide that helps to work with the emergency services in responding to a hazardous material incident. Below is an example of a HAZMAT action Guide (HAG) on one of the MSDS that shows part of the way to deal with a HAZMAT incident. On larger building sites there is often many different hazardous materials that require MSDS to be kept on file and easily accessible. When there are multiple MSDS kept on file an MSD register should be kept to ensure that they can be easily found when required and also to ensure that the MSDS do not go out of date. You will find an example MSDS on the next page. 44 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 45 46 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 Additional Learning Resource 1; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 47 48 Additional Learning Resource 1 ; CPCCBC4002A © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, Dec 2013 OHS FORM 10: HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE REGISTER AND RISK ASSESSMENT Product name Application Product labelled? (Yes/No) P0049672 Section 3 - Learning Resource; CPCOHS2001A Ed2 © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, June 2013 MSDS date of issue no older than five years? (Yes/No) Risk rating (1–6) Controls to be implemented Note: Incorporate these controls into the SWMS 49 The minimum standard for MSDS’s is the National Occupational Health and Safety Commission (NOHSC or Worksafe Australia). The standard is often talked about as the Worksafe Guidance Note on MSDSs. This guidance note gives a standard format for an MSDS, with four major section headings: • IDENTIFICATION • HEALTH HAZARD INFORMATION • PRECAUTIONS FOR USE • SAFE HANDLING INFORMATION In keeping a register of MSDS all MSDS’s should be checked to ensure they conform to Worksafe Australia guidelines before adding them to a catalogue or register. How to ensure an MSDS does conform to standards? • • • • 50 When there are blanks under headings The Guidance Note says: "All sections of the MSDS should be completed...If no information is available on some properties or if available information indicates there is no hazard, then this should be clearly stated, as blank sections tend to confuse or be misleading." When the format (the headings and the order of the heading) is not the same as the Guidance Note The Guidance Note says: “Use the MSDS Checklist to tell you some of the headings that should be there, and what order they should be in.” When the MSDS says "Confidential" or "Confidential – not to be copied". The Guidance Note says: "Employees should have ready access to material safety sheets and this Guidance Note, and receive instruction on their content, with particular emphasis on Items which are most relevant to their workplace." When the MSDS uses terms you don’t understand including abbreviations which don’t make sense. All MSDS’s should contain information that is written in plain English and be understandable to all P0049672 Section 3 - Learning Resource; CPCOHS2001A Ed2 © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, June 2013 • • When the MSDS is an overseas MSDS referring to overseas addresses, regulations and standards. According to the Guidance Note from Worksafe the MSDS...must be relevant to Australian conditions. A MSDS that does not reference Australian conditions or is not in English should be rejected and a conforming MSDS should be requested. When the MSDS is more than 5 years old. MSDSs should be reviewed at least every 5 years. Look for the heading Date of issue of the MSDS. If the date is older than 5 years an updated MSDS should be requested. P0049672 Section 3 - Learning Resource; CPCOHS2001A Ed2 © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, June 2013 51 Electrical/lighting On any building site one of the biggest hazards that is always present is Electricity. There are clear guidelines on how to manage electricity within a building site environment. Below is an outline of some of the issues. CF MEU 1999 Electricity Kills it is crucial that all electrical equipment be tested and tagged in accordance with legislation. WorkCover requires all electrical equipment on a building site to be tested and Tagged monthly including testing of all safety switches and temporary distribution boards on a building site. In order to comply with the above a qualified electrician will be able to ensure your site complies. This is not something you can do yourself you must use a licensed individual. 52 P0049672 Section 3 - Learning Resource; CPCOHS2001A Ed2 © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, June 2013 Bibliography Is it Safe? CFMEU national Safety Manual 2nd edition. Basic Building & Construction skills edition 3 Carpentry & other general construction trade. TAFE NSW south western Sydney Institute. Pearson Longman 2005. Hazard Identification & Risk assessment Manual for small builders, Workcover NSW Standard Publishing house 1996. Safe Working at Heights Guide 2004. Workcover and NSW construction industry Reference group. Workcover publications catalogue 1321. Safety Handbook Edition 1, Building Trades group of Unions, 2008 http://www.workcover.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Publications/OH S/Risk%20Management/fact_dermatitis_4103.pdf P0049672 Section 3 - Learning Resource; CPCOHS2001A Ed2 © New South Wales, Department of Education and Communities 2013, Version 1, June 2013 53