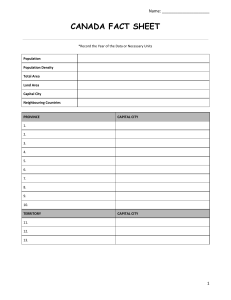

Word count: 9119 Department of History School of Social Sciences Ateneo De Manila University Loyola Height, Quezon City The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment: The Public Education System of the Moro Province, 1903-1913 by Albert Rafael E. Umali III IV-AB History An Undergraduate Thesis submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Bachelor of Art in History Quezon City April 2023 Word count: 9119 Table of Contents List of Maps 1 Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 I. Aim, Topic, & Research Question/s 3 Research Topic 3 Research Question/s 5 II. Historiographic Essay 5 Scholarly works on the history of Education in the Philippines 5 Works of Influential figures on the creation Public Education System of the Philippine Islands 7 Scholarly works on the Moro Province 9 Scholarly Work on other forms of Education in the Moro Province 9 III. Significance and Contribution 10 IV. Method and Approach 10 V. Scope and Limitation 11 VI. Sources and Repositories 12 VII. Proposed Thesis Structure 13 VIII. Milestones and timeline of First and Second Semesters 14 CHAPTER 1 15 The Educational Landscape: Education in Mindanao prior to the Moro Province 15 The emergence of the “Pandita” / Madrasah education system 15 Spanish Era / the Jesuits missionaries 17 The arrival of The Americans – Education during the Military Occupation 18 CHAPTER 2 21 The “Designers of Knowledge”: The Educational Philosophies of the Governors of the Moro Province 21 The “Designers” of Knowledge 22 General Leonard Wood: The First Governor of the Moro Province 22 Tasker H. Bliss: the Second Governor of the Moro Province 24 General. John J. Pershing: The Last Governor 25 CHAPTER 3 28 The Educational Diversity: Religious schools and the Emergence of Secular Public schools 28 The Pandita schools and the Emergence of a Secular public school 29 Parochial Schools and the Emergence of a Secular public school 31 CONCLUSION 32 Bibliography 34 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 1 List of Maps Map Map 1. The Moro Province 1903-1913 Map 2. Jesuit Missionary Stations in Mindanao 1900-1929 3 16 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 2 Acknowledgements The completion of this research would not have been possible, if not for the constant encouragement and constructive criticisms of my dear colleagues, Bea Alejandro, Lia Castro, Caitlin Enriquez, Charlie Soriano, Nicolo Del Rosario, Keith Macapagal, Kiko Tallada, Bea Magbanua, and Raine Rivas. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude towards the staff of the American Historical Collection of the Rizal Library, especially to Sir. Bhal Rabe, who helped me in finding relevant primary sources that I was able to use in strengthening my research. I would not have been able to survive my four years as a history major at the Ateneo De Manila University without the aid and kindness of Ms. Kristine A. Sendin the History Department Secretary, that has always been ready to provide assistance and guidance. My sincerest appreciation extends as well to Dr. Patricia Dacudao, my thesis adviser who inspired me to pursue my research topic through her Mindanao Studies subject that opened my eyes to the rich and unexplored history of Mindanao and for her unyielding support that allowed me to improve and polish my senior thesis. Lastly, my sincerest gratitude and thanks to my family who have always believed in and encouraged me to not only pursue my research topic but as well as my passion for history and so I dedicate to them all of my hard work. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 3 Introduction I. Aim, Topic, & Research Question/s Research Topic During the early years of the American occupation of the Philippine Islands, the American government along with the Philippine Commission formally initiated the establishment of a public school system in the country in 1901. Subsequently, in 1902, the United States Congress passed the “Philippine Bill” - that established and recognized the necessity of establishing different forms of government for the Pagan, Christian, and Muslim population of the Philippine Islands (P.I.)1. In line with this, The American colonial government saw the need to establish a separate governing body for the Muslim Filipinos in the southern part of the P.I. - The Moro Province (M.P.). With the passing of the Philippine Commission of Act No. 787 - “An act Providing for the Organization and Government of the Moro Province ” - The Moro Province was formally inaugurated on July 15, 1903. The newly formed Moro Province consists of five districts - Sulu, Cotabato, Davao, Lanao, and Zamboanga where the Capital city was located (refer to Map 1). In line with Act No. 787 - the implementation of public education in the Moro Province became separate from that of the Bureau of Education and will be directly supervised by the Superintendent and the governor of the Moro Province. According to Gen. Leonard Wood the first Governor of the province - “In constrast to previous policy, the Moro Province sought to build its own school buildings and conduct its own school system independent of municipal influence or control”2. 1 United States Congress, and Philippine Commission. An Act providing for the Organization and Government of the Moro Province, 787 § (1903). https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/28/37265. 2 Peter Gordon Gowing, Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 4 Aim of the Research This study aims to trace the expansion and development of the public education system implemented in the Moro Province through the actions and decisions of its leaders. Through this examination, the study aims to uncover the factors that impeded and aided the education of Muslim-Filipino and Christian-Filipino residents of the Moro Province. In line with this, the study aims to study the educational philosophies and views of significant figures in the Moro Province and how these affected the creation and implementation of Public Education in the region. In addition, this study will also discuss how the presence of other forms of educational institutions in the region affected the establishment of the public school system. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 5 Research Question/s What were the different educational policies that influenced and guided the expansion and development of the public education system in the Moro Province, 1903-1913? Sub-Question 1: Did the views on Education of the Educational Superintendents, Directors, and Governors of the Moro Province influence the development of the Educational system in the Province? Sub-Question 2: What were the challenges in establishing a public education system for the Moro population of the Moro Province? Sub-Question 3: Did the presence of Pandita and Parochial schools in the province, affect the establishment and development of the public education system? II. Historiographic Essay This section of the paper is intended to introduce each of the chosen pieces of literature and provide general ideas and perspectives about them. In addition, this section is to provide the relevance and connection of each of the works with the aim of the research. Scholarly works on the history of Education in the Philippines There have been many scholars who have tackled the educational history of the country. Works such as The Philippine History: Political, social, Economic by Eurfronio M. Alip (1958), In A Century of Education in the Philippines 1861-1961 by Dalmacio Martin (1980), and The Philippines Past and Present by Dean C. Worcester (1914), provides an overview of the Education of Filipinos under American Colonization. All three scholarly works gave information on the different kinds of schools established during the American period and the aims behind them ((i.e., Agricultural schools, Philippine Nautical Schools, Normal schools, etc.). In spite of their similar subject matter, the scholarly works presented have some differences, Dalmacio Martin’s work mentions the changes in curriculum over the The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 6 two-decade period3. In addition, both Alip and Martins’s work contained a separate section dedicated to the education received by Non-Christian Filipinos such as the Muslims of Mindanao. Following these scholarly works is the journal article written by Prof. Renato Constantino (1970), entitled The Miseducation of the Filipino, in this article he stated that, “Education is a vital weapon of a people striving for economic emancipation, political independence and cultural renaissance”4. Furthermore, he tackles briefly the beginnings and goals of American education and how these affected the education of Filipinos5. In 1901 the American Civil Government in the Philippines, passed the educational Act of 1901, or Act no. 74 giving way for the establishment of the Department of Public Instruction6. However, it must be noted that the Reports of the Department of Public Instruction contain mostly educational data concerning Christian Filipinos, and only allotted a section devoted to the education of Non-Christians especially the Muslims of Mindanao. This is due to the fact that at the time the Educational reports of the Moro Province is separated from that of the rest7. Moreover, the annual report of the General Superintendent of Education in 1908, contains information on the progress of public instruction in the Philippine Islands. In addition to this, is a report on the difficulties or the problems American educators faced in establishing public schools in the Moro Province. One example that was stated is, “The presence in the Moro Province of different peoples antagonistic to one another in religion and culture makes the school problem there very difficult”8. Furthermore, the report of 1907 also stated a notable difference between the instruction of Christian Filipinos and the Muslim Filipinos, “...some differences have been developed, notably the teaching of reading and writing of Moros in their native dialects, written, as these dialects regularly are, in the Arabic character”9. 3 Martin, Dalmacio, ed. “Chapter IV: Philippine-American Educational Partnership, 1898-1935.” In A Century of Education in the Philippines 1861-1961, 165–97. Manila: Philippine Historical Association, 1980. 4 Constantino, Renato. “The Miseducation of the Filipino.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 1, no. 1 (1970). chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://nonlinearhistorynut.files.wordpress.com/2010/02/miseducatio n-of-a-filipino.pdf. 5 Constantino, The Miseducation of the Filipino, 1. 6 Estioko, Leonardo R. History of Education: A Filipino Perspective, 187-197. LOGOS Publications, Inc., 1994. 7 Department of Public Instruction, Bureau of Education. “Annual Report of the General Superintendent of Education [1904].” Annual, 1904. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. 8 Department of Public Instruction, Bureau of Education. “Annual Report of the Director of Education [1908].” Annual, July 1, 1907. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. 9 Department of Public Instruction, Bureau of Education, Annual Report of the Director of Education [1908] The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 7 The following are scholarly works describing the educational history mainly of the Christian provinces but also dedicated a section on Non- Christian Filipinos (i.e., the Muslim Filipinos in the Moro Province). Both, A History of the Education in the Philippines 1565-1930 by Encarnacion Alzona and History of Education: A Filipino Perspective by Leonardo R. Estioko provided a survey of the education received by Christian Filipinos and Non- Christian Filipinos like Muslim Filipinos. Wherein, both literature outlines the organization of the public school system. Estioko’s book provided information on the structure of the school system and a partial list of tertiary-level institutions established during this era.10 Furthermore, Alzona's book dedicated a section on Non-Christian Filipinos, describing the progress and problems faced in implementing the educational policies. One such problem that was mentioned was attracting or convincing Muslim parents to send their daughters to schools11. Part Three of the Social Engineering in the Philippines: The Aims and Execution of American Educational Policy, 1900-1913 by Glenn A. May, provides a detailed history of the Educational system in the Philippines during the early years of the American Colonization through following the administrations of three General Superintendent / Directors of the Bureau of - Fred Atkinson, David Barrows, and Frank R. White and the Governor General of the Philippine Islands - William Cameron Forbes. The book expounded on the different reforms and educational policies enacted in each term12. Works of Influential figures on the creation Public Education System of the Philippine Islands Dean C. Worcester (1914) a U.S. official who served as secretary of the Interior for the U.S. Insular Government in the Philippines from 1901-1913, wrote a book entitled The Philippines Past and Present - in this book Worcester traced Philippine History from the Spanish era to the early years of the American colonization. His book, in addition, expanded on the educational system being implemented in the Philippine Islands (P.I.) - he states how “American teachers were quick to see these vagrant arts could be organized and 10 Estioko, Leonardo R. History of Education: A Filipino Perspective, 187-197. LOGOS Publications, Inc., 1994. Alzona, Encarnacion. A History of the Education in the Philippines 1565-1930. 1st ed. Manila: University of the Philippines, 1932. 12 May, Glenn Antony. Social Engineering in the Philippines: The Aims, Execution, and Impact of American Colonial Policy, 1900-1913, 1980. 11 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 8 commercialize.” - that resulted in courses such as pillow lace-making, Irish crochet, hat weaving, and many more to be introduced in the primary and also intermediate schools throughout the country13. Following Worcester is a book by the first General Superintendent of the Public Schools system in the Philippines - Fred W. Atkinson (1905). In this book entitled, The Philippine Islands - Atkinson similarly to Worcester wrote about the history of the Philippine Islands up to the arrival of the Americans. Included in his book is a section about education wherein, he detailed the story of the educational development in the country. In this section, he detailed the history of Philippine education from the Spanish era to the early American period. He stated the shortcomings of the Spanish in establishing an effective educational system in the country - “The system lacked completeness and sufficiency, and although it is true that at the time of the coming of the Americans, some 2150 public primary schools were in operation, a knowledge of the character of the work carried on in them detracts seriously from the importance with which such a statement as this might otherwise be received”14. Furthermore, Atkinson stated that it is through the intervention of the American government that led to the “...enlivened interest in educational matters”15. Barrows (1914) expanded on the status of the development of Public education in the P.I. - Barrows stated that through the continuing efforts of the American Insular government in the Islands - Filipinos have recognized and sought further education - high schools. “The high schools are the real intellectual and social centers for each province and have commanded the fullest enthusiasm of the Filipinos, who have made sacrifices to gain them”16. In addition to this, Barrows explained the main features of the public school system - focus on industrial work and athletics. Industrial courses have been injected into every stage of education from primary to high school. The book of Dr. Najeeb M. Saleeby entitled the “Language of Education” - argues and defends the idea that the use of the English Language as the sole medium of instruction can impede the students learning. Dr. Saleeby states that “Elementary education should improve the intelligence of the pupil and prepare him for a productive and progressive life” 13 Worcester, Dean C. The Philippines Past and Present. Vol. 2. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. 14 Atkinson, Fred Washington. The Philippine Islands, by Fred W. Atkinson., 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/abf2839.0001.001. 15 Atkinson, 381. 16 Barrows, David Prescott. A Decade of American Government in the Philippines, 1903-1913, by David P. Barrows ..., 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ahz9396.0001.001. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 9 and to accomplish that the language of instruction should remain to be his own native tongue. Moreover, Dr. Saleeby expounds on the advantages of using the native tongue in effectively forming and shaping the pupils’ habits and character17. Scholarly works on the Moro Province The materials presented below are government documents and scholarly works that pertain to the establishment and various development of the Moro Province. Scholarly works that depict the education of Muslim Filipinos. The Muslim Filipinos: Their History, Society, and Contemporary Problems by Antonio Isidro, Chapter 3 - Civilizational Imperatives: Building Colonial Classrooms.”, In the Civilizational Imperatives: Americans, Moros, and The Colonial World by Oliver Charbonneau (2021) and Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920 by Peter Gowing (1983), provide extensive information on the perception and reaction of Muslim Filipinos to the Colonial public educational system. In addition, both books provide a glimpse of the development of public education in the region. All of the works depicted the American Educational campaign as a failed attempt to pacify the Muslims of the south. Peter Gowing’s Mandate in Moroland - provides a detailed description of the administration of the three governors of the Moro Province. In addition to this, the Mandate in Moroland gives a detailed history of the Moro Province and how various key players in the colonial government influenced the education of the Muslim Filipinos18. Scholarly Work on other forms of Education in the Moro Province There has been a cursory historical study on the educational landscape in Mindanao before the arrival of both the Spanish and the Americans. In the Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries by Jonathan Victor Baldoza (2022), he explores the history of the Panditas as both an influential individual within the Muslim-Filipino community that performs various rituals and also conducts classes on Islamic history and traditions19. Following Baldoza is the View of Issues on Islamic Education in the Philippines by Marlon Gulen, Razaleigh Kawangit, and Zulkefi Aini (2017), they tackled the current issue of Islamic education in the Philippines and how Islamic education contributes greatly to the 17 Saleeby, Najeeb M. “Elementary Education Should Be Given in the Mother Tongue,” March 9, 1925. Peter Gordon Gowing, Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920. 19 Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. “The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries.” Archipel. Études Interdisciplinaires Sur Le Monde Insulindien, no. 103 (August 30, 2022): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2969. 18 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 10 development of the relationship between Muslims and Christian20. In order to investigate this, the authors delve into the history of Islamic education in the country21. III. Significance and Contribution This research aims to fill the historical gap within the present historical literature on the public education system implemented and developed in the Moro land. After reading and analyzing, the existing related literature, the researcher found that the majority of the secondary sources on the history of Philippine education, have yet to fully tackle the nuances of the public school system implemented during the American period for the education of Muslim Filipinos in the southern region of the Philippines. There has been a cursory study on this topic such as Peter Gowing’s Mandate in the Moroland, however, his book only touched upon the various achievements of the three governors of the Moro Province. In line with this, the researcher aims to contribute to the body of literature on Philippine Education under the American era by tracing the development of the public school system in the Moro Province through the perspective of the Governors and other policymakers of the province. Through re-examining how the Public school system was introduced in the Moro Province the researcher hopes to uncover the possible influences of the educational philosophies of the key policymakers in the region on the development and expansion of the public school system in the Moro Province. Furthermore, the researcher hopes through tackling the challenges and successes of implementing the public school system in the Moro province, may provide some perspective to aid in finding solutions to the current problems facing public education such as the decreasing quality of education22. IV. Method and Approach This research will utilize archival research methods in collecting and analyzing the acquired primary data on the educational development within the Moro Province. Archival research is defined as a historical research method that “employed historical materials to 20 Guleng, Marlon Pontino, Razaleigh Muhamat@Kawangit, and Zulkefli Aini. “Issues on Islamic Education in the Philippines: Isu-Isu Pendidikan Islam Di Filipina.” Al-Irsyad: Journal of Islamic and Contemporary Issues 2, no. 1 (June 20, 2017): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.53840/alirsyad.v2i1.22. 21 Guleng 22 Childhope Philippines Foundation, Inc. “Education Issues in the Philippines: The Ongoing Struggle,” August 25, 2021. https://childhope.org.ph/education-issues-in-the-philippines/. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 11 study the emergence of distinctive institutional arrangements”23. In line with this, the thesis will employ two archival research goals, first is Studying Structural embeddedness - which looks into certain individuals, organizations, and institutions that have been embedded within “relational networks” that influence the development and ideas of a given geographical area through the dominant ideology24. And lastly, is Studying Meaning Structures - wherein the research goal is to examine the “shared understanding, professional ideologies, cognitive frames or sets of collective meanings” that influence how relevant actors or institutions view and interpret the world around them25. In line with this, a Top-Down approach will be utilized in this research, to examine and review the pertinent government documents that tackle the educational development of the Moro Province. With this methodology, the researcher will trace the development of the public school system in the Moro Province through the examination and analysis of the annual reports and articles written by the various governors and Superintendents of Schools in the province. V. Scope and Limitation This study will focus on tracing the development of the educational system implemented in the Moro Province. The time frame of the study will be from 1903-1913, the ten-year period wherein Mindanao was under the jurisdiction of the Moro Province. In terms of the scope of the educational factors, the research will take into account the educational philosophies and views of the key policymakers in the Moro Province and the corresponding memorandums, bulletins, and directives accessed through the reports of the Governor General of the Moro Province, and the reports of the Superintendent of the regions. In addition to this, the study will mainly focus on the Christian residents and the Muslims of the Moro province. It will not tackle the development of public education in the other parts of the Philippine Islands nor the other non-Christian tribes in the island of Mindanao or within the Moro Province. 23 Mohr, John, and Marc Ventresca. “Archival Research Methods,” 805–28, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405164061.ch35. 24 Ibid 25 Ibid The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 12 VI. Sources and Repositories The primary sources used by the researcher in conducting this research were mainly accessed and reviewed at the Ateneo De Manila University. All of the primary sources - e.g., the annual reports of the Bureau of Education - Department of Public Instruction, the annual reports of the governor of the Moro Province, the report of the 1st Philippine Commission, the survey report of the education of the Philippines by the Board of Educational Survey, and the book of Dean C. Worcester entitled, “The Philippines Past and Present”, were all found and accessed in the American Historical Collection. The American Historical Collection (AHC) is a repository of historical materials such as books, photographs, and government documents about the American period in the Philippines. In line with this, the researcher would like to acknowledge the aid given by Sir. Bhal Rabe and the staff of the AHC in finding the primary sources used in this research. In regards to the secondary sources, the researcher was able to access them mainly through the Ateneo De Manila University - Rizal Library. Sources such as A Century of Education in the Philippines 1861-1961, The Muslim Filipinos: A Book of Readings, History of Education in the Philippines, and History of Education: A Filipino Perspective, were all found in the Filipiniana section. In addition, there were also secondary sources used by the researcher from the American Historical Collection - e.g., A History of the Education in the Philippines 1565-1930, The Muslim Filipinos: Their History, Society, and Contemporary Problems, Philippine History: Political, Social, Economic, and The Muslim Filipinos: Their History, Society, and Contemporary Problems. In addition to this, the researcher was also able to acquire secondary and primary sources in online repositories such as the University of Michigan Library’s Southeast Asian Collection - e.g., The Philippines past and Present, The Philippine Islands, and A decade of American government in the Philippines, 1903-1913. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 13 VII. Proposed Thesis Structure This thesis intends to be a cursory survey of the development of the establishment of the public school system in the Moro Province, and the landscape of education in the province during its 10-year period of semi-autonomous statehood. Our story begins, with chapter 1, where the study will illustrate the educational landscape prior to the arrival of the Americans and the establishment of the Moro Province. Chapter 1 will look into the various educational systems or forms of it that have existed in the region, from the pre-colonial pandita schools, The Spanish period’s parochial / Catholic missionary school run by Jesuit missionary priests, and the early American period, with the embryonic public education during its military occupation. After which, Chapter 2 and Chapter 3, will look into the experiences and reports of the Governors & Superintendent of schools of the Moro province in establishing a secular public school in the Moro Province. Chapter 2 specifically will look into the perception of the education of the governors of the Moro Province and how these educational philosophies have shaped their actions and decisions in establishing the public school system in the M.P. Chapter 3, the last chapter of this thesis, will discuss how the American governors of the Moro Province, reconciled with the presence of non-secular schools in the region such as the long-standing, Pandita schools of the Muslim-Filipinos and the Parochial Schools of the Christian-Filipinos. And lastly, the conclusion will summarize the main points of the thesis and provide future recommendations and the limitations of the study. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 14 VIII. Milestones and timeline of First and Second Semesters Proposed Schedule of Thesis Writing Albert Rafael E. Umali III, 4 AB History The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment: The Public Educational System of the Moro Province Academic Requirements Timeline Research Proposal Submission date: November 11, 2022, Word count: Oral Presentation Submission date: November 17, 2022, Full Senior Thesis Draft Submission date: December 9, 2022, Word count (max): Proposed Thesis Chapters Timeline Chapter 1: The Educational Landscape: Education in Mindanao prior to the Moro Province deadline: February 7, 2023, Word count: 1663 Chapter 2: The “Designers of knowledge”: The Educational Philosophies of the Education Superintendents and directors. deadline: February 28, 2023, Word count: 2093 Chapter 3:The Educational Diversity: Religious schools and the Emergence of Secular Public schools deadline: March 23, 2023, Word count: 1,295 Introduction deadline: March 31, 2023, Word count: 3346 Conclusion deadline: March 31, 2023, Word count: 500 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 15 CHAPTER 1 The Educational Landscape: Education in Mindanao prior to the Moro Province This Chapter will trace the educational landscape of Muslim Filipinos in the southern Philippines prior to the creation of the Moro Province. Detailing the varied educational systems encountered and experienced by the Muslim Filipinos from the Pandita Schools, Catholic Missionary schools, and early American public schools and exploring the different educational aims and perspectives on education of each system. In addition, the chapter explores how educational systems can be utilized as a tool for preservation, conversion, or suppression. With this in mind, Chapter 1 will be answering the following research questions: (1) What was the educational landscape of Mindanao prior to the formation of the Moro Province? (2) What were the educational aims of the different educational systems in each era? And lastly, (3) How did the Muslim Filipinos react to the different educational systems they encountered? The emergence of the “Pandita” / Madrasah education system Prior to the arrival of western colonial powers such as Spain and the United States, the inhabitants of Mindanao were already exposed to an Islamic education system brought by Arab missionaries during the late 13th to early 14th century along with the Islamic faith26. This Islamic education system was known as Madrasah/Madrassa system or prior to the colonial era as “Pandita”27. The term pandita was derived from a Sanskrit word that means “Learned teacher” and “Master”28. The Pandita or Madrasah system would resemble a tutorial system wherein Panditas or “gurus” would conduct classes in mosques or at the homes of the Panditas or influential individuals in the community such as the Datu29. As a result of this, the Panditas were regarded in high esteem by the community, even described by a British 26 Lantong, Abdul M. “The Islamic Epistemology and Its Implications for Education of Muslims in the Philippines,” 67–71. Atlantis Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2991/icigr-17.2018.16. 27 Samid, Amina H. “Islamic Education and the Development of Madrasah Schools in the Philippines.” International Journal of Political Studies 8 (August 2022): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.25272/icps.1139650. 28 Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. “The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries.” Archipel. Études Interdisciplinaires Sur Le Monde Insulindien, no. 103 (August 30, 2022): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2969. 29 Lantong, Abdul M. “The Islamic Epistemology and Its Implications for Education of Muslims in the Philippines,” 67–71. Atlantis Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2991/icigr-17.2018.16. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 16 observer as “…almost the chief in his district – not in the warlike sense, like the Datto; but his words has great influence.”30. This system can be categorized as religious in nature, wherein the gurus would teach students passages from the Qur’an, furthermore, the Panditas also taught them the Arabic writing system and basic arithmetic31. Moreover, education during this period was limited to “vocational training and fewer academics by their parents and in houses of tribal tutors”32. The prevailing educational aims in both Muslim and non-Muslim communities are focused on “survival, conformity, and enculturation”33. In line with this, the teaching methods utilized by Islamic gurus, were “show-and-tell, observation, trial and error, and imitation”34. In addition to this, the Panditas were described to be “travelling ‘teachers’” that spread and preserve the Islamic faith35. The Madrasah education was credited to aid in the preservation of the Islamic faith in the Southern Philippines despite the numerous attempts of colonizers like Spain to dismantle the faith36. Though there are no substantial evidences that could provide the scale the scope of this Pandita education system. Nevertheless, The pandita school was able to achieve this by focusing on the integration of the Islamic faith and traditions into the Filipino Muslim youth through education. 30 Foreman, John. The Philippine Islands: A Political, Geographical, Ethnogrpahical, Social and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago. Third. Filipiniana Book Guild, 1906. 31 Ibid 32 Kulidtod, Zainal Dimaukom. “ISLAMIC EDUCATIONAL POLICIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: ITS EVOLUTION AND CURRENT PROBLEMS.” International Research-Based Education Journal 1, no. 1 (May 29, 2017). https://doi.org/10.17977/um043v1i1p%p. 33 Ibid 34 Ibid 35 Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. “The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries.” Archipel. Études Interdisciplinaires Sur Le Monde Insulindien, no. 103 (August 30, 2022): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2969. 36 Solaiman, Saddam Mangodato. “Implementation of Arabic Language and Islamic Values Education (ALIVE) in Marawi City, Philippines: Unveiling the Perceptions of ALIVE Teachers.” Education Journal 6, no. 1 (February 10, 2017): 38. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.edu.20170601.15. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 17 Spanish Era / the Jesuits missionaries Along with the arrival of the Spaniards saw a new educational system in the form of Catholic Missionary Schools37. The Spaniards were able to establish this new Christian education throughout the Islands of Luzon and Visayas however failing to penetrate the heart of Mindanao. Since the arrival of Spain one of its main objectives was not only to spread the Catholic faith through its missionary Schools but also to subdue and convert the Muslims of Mindanao. However, despite their numerous military campaigns it would take them several decades to establish a military foothold in Mindanao. A few years after Spain and the Sulu sultanate signed a peace treaty in 1851 a royal decree was issued to create a politico-military government in the region. The establishment of Catholic missionary schools in the southern Philippines received significant support from Spanish religious orders, in particular, the Jesuit order played a key part in this endeavor. The Jesuits established stations through out mindanao (refer to Map 2), the first mission was stationed in Tamontaka at the center of “Muslim territory”38. In the compiled Jesuit letters, that was translated and annotated by Fr. Jose S. Arcilla S.J., it was recorded how the Jesuits did not only seek to convert the natives but as well as educate them. 37 Alzona, Encarnacion. 1932. A History of the Education in the Philippines 1565-1930. 1st ed. Manila: University of the Philippines. 38 Arcilla, Jose S. 1978. “The Return of the Jesuits to Mindanao.” Philippine Studies 26 (1/2): 16–34. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 18 In a letter written by Fr. Jose Ignacio to the Mission Superior in 1875, he detailed the regular activities of the libertos in the agricultural institute they have established. “After the noon meal, recreation until 1:30 o’clock, and rest or free time until 2:00 o’clock. From 2:00 to 3:00, reading, writing, and catechetical instructions, immediately followed by work. At sundown, rest or recreation, and around 6:30 o’clock, the Rosary, followed by a few hymns, catechism, practice of Spanish and Moro until 7:45 o'clock. After supper, they recite the prayers, and go to bed”39. This particular letter shows, that the Jesuit missionaries did not only teach the children Spanish but as well as continuing to educate them in their native languages. In the latter part of the letter Fr. Ignacio explains the logic behind this, “…to develop here a Moro-Spanish population who speak some Spanish, are trustworthy…”40. In addition to teaching the children that they have been ransomed out of slavery from Muslim communities, the Jesuits would conduct classes in the tianggi or markets. These catechism classes would be composed of Muslim Filipinos and other non-Christian Filipinos such as the Tirurays41. However, in spite of this, the Spaniards were unable to fully establish and spread their Catholic missionary schools in Mindanao. According to Spanish records, enrollment rates in colonial schools in Mindanao such as in Cotabato and Zamboanga reached about 5 percent of the Muslim youth42. The Jesuit missionaries continued to conduct missionaries and operate missionary schools until the arrival of the Americans. The Jesuits played a key role in supporting the Americans in conquering Mindanao. The arrival of The Americans – Education during the Military Occupation Following the defeat of Spain in the Battle of Manila and the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1899. Even though Mindanao was never fully colonized by the Spanish, Spain transferred the authority of the entire Philippine Islands, including Mindanao, to the United 39 Guerrico, Jose Ignacio. Letter to Mission Superior. “Jesuit Missionary Letters from Mindanao: Jose Ignacio Guerrico to the Mission Superior,” 1875. Rizal Library - Ateneo De Manila University. 40 Ibid 41 Ibid. P. 69 42 Milligan, Jeffrey Ayala. Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 19 States. 43. In 1899 President McKinley express the basic policy of his administration towards the annexation of the Philippine Islands in a message to the United States Congress: “The Philippines are not ours to exploit, but to develop, to civilize, to educate, to train in the science of self-government. This is the part we must follow or be recreant to a might trust committed to us”44. When the Americans first interacted with Muslim Filipinos in 1899, they relied heavily on the guidance of Jesuit Missionaries on how to negotiate and interact with the Muslim Filipinos. The works of the Jesuit missionaries that describe the “characteristics” of the Muslim Filipinos also influenced the perception of American military officers on the character of Muslim Filipinos. The works of Rev. Fr. Pio Pi. S.J. in particular was highly regarded by the American Military government. In a report by Gen. George W. Davis, he included an essay written by Fr. Pi that describes the Muslim Filipinos of Mindanao in the most unflattering light with descriptions such as, “Among the Moros there scarcely exists one who is not a ladron (robber)”45. American Garrisons were sent to strategic locations throughout Mindanao such as Zamboanga and Cotabato. In that same year, Brigadier-General John C. Bates was stationed in Mindanao in order to negotiate with local Datus to establish friendly relations with the Muslim Filipinos – this treaty would be known as the “Bates Treaty”46. However, despite the establishment of the Bates Treaty, the American Military was unable to determine a concrete policy or guide with regard to the treatment of the Muslim Filipinos and other Non-Christian Filipinos in Mindanao47. In April of 1900, President McKinley in a speech provided instruction on the treatment of the Muslim Filipinos and other non-Christians that the American military should adopt a similar policy when treating the North American Indians48. The Mindanao Island, along with the Sulu Archipelago and Palawan was placed under the jurisdiction and supervision of the Military District of Mindanao Jolo in 1899. After a few 43 Gowing, Peter G. Mandate in Moroloand: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920. New Day Publishers, 1983. 44 Harrison, Francis Burton. The Corner-Stone of Philippine Independence: A Narrative of Seven Years. New York: The Century Co., 1922. 45 Ibid, footnote 19 46 Forbes, W. Cameron. The Philippine Islands I. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1928. 47 Ibid, footnote 19 48 Forbes, W. Cameron. The Philippine Islands I. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1928. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 20 years on March 20, 1900, the District was changed into the Military Department of Mindanao and Jolo. Under the Military Department of Mindanao and Jolo, a new educational system was introduced to the inhabitants of Mindanao. A public education founded on a western and secularized system of education49. The teachers that were recruited to teach were a mix of civilians and military personnel, both Filipinos and Americans50. In a report of the War Department, Captain Cloman stationed in Bongao stated that there is a great need for blackboards and chalks for the education of Muslim Filipinos. Furthermore, the Americans viewed the education system they encountered in Mindanao needed to be overhauled and education would need to go back to the basics 51 . In establishing this new form of the education system, the Americans faced challenges from both Christians and Muslims alike, the Americans utilized the “Carrot-and-stick” to solve the dilemma52. Soon as the Philippine Commission was formed and started to take over the governing of the country, the Military officers slowly turned over their duties to the civilian teachers. In spite of this, the governing of the Moroland in the coming years from 1903-1913 would remain in the hands of seasoned American Military generals that have diverse and conflicting educational aims. The Muslim Filipinos of Southern Philippines, have encountered different systems of education. Educational systems have different aims and methods. The Madrasah/Pandita System displayed how education can be an effective tool and weapon to preserve one’s customs and traditions. The Spaniards however, unsuccessful in expanding their Catholic Missionary Schools in Mindanao, showed how education can be a way to persuade and convert an individual. The introduction of a secularized education in the form of public education under the American military occupation would pose a challenge to the long-standing pandita schools that have safeguarded the Islamic youth from conversion. 49 Gowing, Peter G. “Chapter 3: Shaping an American Moro Policy _ Health and Education.” In Mandate in Moroloand: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920, 63–65. New Day Publishers, 1983. 50 Ibid 51 Ibid 52 Charbonneau, Oliver. “Chapter 3 - Civilizational Imperatives: Building Colonial Classrooms.” In Civilizational Imperatives: Americans, Moros, and The Colonial World, 73–93. Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2021. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 21 CHAPTER 2 The “Designers of Knowledge”: The Educational Philosophies of the Governors of the Moro Province The creation of a military government for the Muslim Filipino population of the Southern Philippines was strongly encouraged and supported by Major General George W. Davis of the 7th brigade that was stationed in Mindanao. In a report in 1902, Gen. Davis stated in his recommendations to Governor Taft, that a military government must be in place to properly govern the Muslim Filipinos53. Additionally, Gen. Davis stated in his report to the United States War Department that the American policy of non-interference as stated in the Bates Agreement in 1899 towards the Muslim Filipinos allowed for the Sultan to have excessive “sovereign power” and he hopes that through the creation of the Moro Province (M.P.), the Sultan’s power can be regulated54. The Moro Province was established on June 01, 1903, when the Philippine Commission and the United States Congress passed Act No. 787, or An Act providing for the organization and Government of the Moro Province55. Within this law, the boundaries and purpose of the creation of the province were laid out. The Moro province was divided into five districts, namely, Sulu, Lanao, Cottabato, Davao, and Zamboanga, with the last as its capital56. The provincial government will be composed of “a governor, attorney, secretary, treasurer, superintendent of schools and an engineer”57. The public school system introduced by the Americans was divided into Primary, Intermediate, secondary, and tertiary schools. Along with this, the American school system also offered technical schools such as Normal, Industrial, Agricultural, and Farming Schools58. On the other hand, due to the establishment of the Moro Province in the fall of 1903, the schools of Southern Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago have been administered 53 Davis, George. “Annual Report of Major General W. Davis 1903.” Annual. Manila: War Department, October 1, 1902. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. 54 Davis, George. “General Davis’s Report on Moro Affairs.” Manila: War Department, October 24, 1901. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. 55 United States Congress, and Philippine Commission. Act No. 787 - AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE ORGANIZATION AND GOVERNMENT OF THE MORO PROVINCE. - Supreme Court E-Library, Pub. L. No. Act No. 787 (1903). https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/28/37265. 56 Ibid 57 58 Ibid The Board of Educational Survey. “A Survey of the Educational System of the Philippine Islands (1925).” Survey, 1925. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 22 separately from the Bureau of Education59. In line with this, the Moro province aimed to create its own educational system free from municipal oversight or influence under the direct supervision of the governor of the Moro Province (M.P.) and the Superintendent of Schools60. Despite this the Moro Province shared the same Primary School curriculum with the rest of the country, focusing on the three Rs - mainly reading, writing, and arithmetic61. The “Designers” of Knowledge General Leonard Wood: The First Governor of the Moro Province General Leonard Wood, was a trained physician graduating from Harvard Medical School, he rose to prominence after multiple successful military campaigns, wherein he was awarded the Medal of Honor and was credited for the modernization of the education, sanitation, and other civil services of Cuba when he was appointed its Military Governor in 189962. After his governorship of Cuba, he met with President Theodore Roosevelt who at the time was having difficulties assigning a governor for the newly formed Moro Province in the Southern Philippines. Gen. Wood then volunteered to take the post of governor, which President Roosevelt gladly accepted. President Roosevelt, gave Gen. Wood absolute control of the province and said to him in the effect of - “Your authority is absolute, The Military forces necessary to back up your decisions are under your direct orders. We want results. The blame or credit for the results you obtain will all be yours”63. As governor of the Moro Province, as prescribed by Act No. 787, which established the Province, the role of the Governor of the Moro Province is to maintain peace and order in the province and subsequently, see to the advancement of education, health, and infrastructure for the interest of the public64. In line with his mandate, Gov. Wood gave particular attention to the development of public instruction. When he assumed the 59 Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. Gowing, Peter G. “Chapter Eight: John J. Pershing: The End of the Moro Province, 1909-1913.” In Mandate in Moroloand: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920, 212–18. New Day Publishers, 1983. 61 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1905], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1905.001. 62 Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Leonard Wood | United States General | Britannica.” Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leonard-Wood. 63 Wood, Eric Fisher. “Chapter XIII: Governor of the Moro Province.” In Leonard Wood: Conservator of Americanism, 216–36. New York: George H. Doran Company, 1920. 64 United States Congress, and Philippine Commission. Act No. 787 - AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE ORGANIZATION AND GOVERNMENT OF THE MORO PROVINCE. - Supreme Court E-Library, Pub. L. No. Act No. 787 (1903). https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/28/37265. 60 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 23 governorship of the province, in 1903 the state of public education was still at its embryonic stage, wherein except for the secondary school in Zamboanga, the rest of the schools in the Moro Province were only primary schools65. However, through the course of his term with the aid of the Superintendent of Schools - Dr. Najeeb Mitry Saleeby, public education saw new developments with the opening of secondary schools, a trade school, and a normal school66. When Gov. Wood first arrived in the Moro Province, both the Christian-Filipinos and Muslim-Filipino students preferred to attend Parochial and Pandita schools respectively67, however, after the establishment of new school buildings, slowly, the enrollment rates of Christian-Filipinos and Muslim-Filipino students in public schools began to increase with 570 Muslim-Filipino students and 79 Bagobos and Christian-Filipinos by School year 1905-190668. Along with the increase in enrollment was the hiring of more teachers to meet the needs of the growing student population. By July 1906, the M.P. hired 22 American Teachers and 67 native teachers wherein 56 are Christian Filipinos and 11 are Muslim-Filipinos69. The majority of the Christian-Filipino teachers were from the Christian regions of the country, while the Muslim-Filipino teachers were trained in the Normal School in Zamboanga70. Gov. Wood from his reports emphasized the importance of English as the language of instruction and sought to enforce it. In addition, to this Gov. Wood also stated that the preservation of the native languages would only prove to be a hindrance in establishing a cohesive society, especially in conducting official business in the future71. Moreover, Gov. Wood expressed the need for proper and strict discipline of students, stating that corporal punishment can be and should be utilized to maintain order and compel obedience among students to facilitate effective learning. Adding that teachers would not be punished if they chose to employ such methods72. Gov. Wood's governorship of the Moro Province also saw the passing of Act No. 167 which ordered the compulsory attendance of all children who are eligible to attend school73. In the same report, he expressed that an education that is focused on developing the 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1905], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1905.001. Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1906], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1906.001. Ibid Ibid Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1906], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1906.001. Ibid The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 24 agricultural and industrial skills of the students of the M.P. is of the utmost importance. He also stressed the significance of prioritizing education that would strengthen and advance a positive view of the government. Gov. Wood viewed education as means to civilize the population of the M.P. through promulgating modern ideas to the youth, especially to the Muslim-Filipinos and other non-Christian Filipinos that in his words “having no conception of them [modern ideas] at all”74. He stated that these ideas are not solely that of Americans but of any modern civilized society75. Furthermore, he stated that the Moro Province was established and was governed separately from the rest of the country due to a “peculiar condition” - which was the presence of the Muslim Filipinos, he then explained that the kind of education and the system of instruction must be flexible in order for Muslim-Filipinos to learn that “Civilization is physically stronger than barbarism”76. Tasker H. Bliss: the Second Governor of the Moro Province Gen. Tasker Howard Bliss was a U.S. military commander who was promoted to Brigadier general after serving as chief of staff for General James H. Wilson in Puerto Rico77. After the departure of General Leonard Wood, Gen. Bliss assumed the position of Governor of the Moro Province. During his governorship, he continued the Educational policy of his predecessor that focuses on the instruction of agricultural and industrial skills78. In his 1907, report Gen. Bliss stated that there is a great need for the encouragement of Muslim-Filipino students due to the low enrollment rates. According to the report of assistant superintendent Charles R. Cameron, the enrollment for the school year 1906-1907 was as follows, “4,414 Christian Filipinos, 793 Moros, 165 Pagans, and 22 Americans”79. However, in spite of this, 58 schools were active - with 55 primary schools, 2 industrial schools, and a provincial school located in Zamboanga80. Industrial education was prioritized, at the primary level - the courses include, stick laying, slat-plaiting, block-building, and mat weaving. These courses are designed to train students for their future 74 Ibid Ibid 76 Ibid 77 Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Tasker Howard Bliss | United States Military Leader | Britannica,” January 11, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tasker-Howard-Bliss. 78 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1907], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1907.001. 79 Ibid 80 Ibid 75 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 25 occupations. Gen. Bliss agreed with the recommendation of the superintendent of schools that the education of the students must be aligned not with that of the American or European way of life but rather with the realities of their native land which in his words are largely “primitive conditions”81. Gen. Bliss during his term recognizes that despite the low enrollment rates of Muslim-Filipino students in the public school system, the majority of these students are being educated in Pandita Schools - in which students are taught courses that only tackle the Islamic faith. He recommended that in order to supplement their studies, there is a need to procure books written in their native language that contains “ arithmetic, geography, government, sanitation, and matter of general information…”82. By doing so, these books can as well as bridge the learning gap of those students that cannot be reached by the public school system. In an article published in the Mindanao Herald in 1909, Gen. Bliss shared his view on the education of children. He explained that despite the apprehension of Americans on the use of despotism, a form of mild despotism is needed to properly educate students. He added, that children are “Habits of order”, and that there is no need for any physical or mental pressure for them to be obedient to their parents or teachers83. General. John J. Pershing: The Last Governor General John Joseph Pershing was a graduate of West Point the United States Military Academy. Prior to being appointed as Governor of the Moro Province, in 1899, Gen. Pershing was stationed in Mindanao to conduct several military campaigns against the Muslim Filipinos. After serving in Japan during the Russo-Japanese war he was promoted to Brigadier General and soon after he returned to the Philippines to replace Gen. Bliss as the Governor of the M.P.84. During his term as governor, Gen. Pershing focused on utilizing public schools as a way to promulgate knowledge concerning the matter of proper sanitation. Along with this, he also focused on the incorporation of military drills to instill discipline among students85. 81 Ibid Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1909], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1909.001. 83 Bliss, Tasker H. “The Government of the Moro Province and Its Problems.” The Mindanao Herald Publishing Company. February 3, 1909. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. 82 84 Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “John J. (Black Jack) Pershing | Biography, Facts, & Nickname | Britannica,” January 22, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-J-Pershing. 85 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1910], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1910.001. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 26 However, despite this, Gen. Pershing still followed the views of his predecessors that the focus of education should still be on the development of industrial and agricultural skills as these will significantly contribute to the improvement of the province86. He further added that “No greater blessing can come to native children than a knowledge of how to perform some kind of profitable labor and do it to the best advantage”87. For the School year 1909-1910, the attendance rate for the M.P. was considerably lower compared to the previous academic year due to the spread of cholera and military upheaval in the province such as the mutiny in Davao and skirmishes with the Jikiri a band of outlaws88. Gen. Pershing, following in the footsteps of his predecessor Gen. Bliss, continued to support the operation of Pandita schools as a way to supplement the government’s public school system. However, he stated in his report that the books that are being used in these schools are regularly checked to ensure their accuracy89. In line with this, he reported that seven new Pandita schools were opened near the shores of Lake Lanao. Gen. Pershing also mentioned in his report that three schools were opened in the Sulu Archipelago, to which the superintendent of School Charles R. Cameron shared his great excitement -“The three schools opened among the Sulu Moros mark the era of peace which a strong government imposed upon that sometime turbulent archipelago”90. Gen. Pershing in his memoir, mentions that the emphasis on industrial and agricultural education was rooted in their view that it is the most effective avenue for native children to have employment opportunities. He further added that this kind of education is more suitable than that of higher learning because it provided the most optimal way for students in the future to better serve the community and improve one’s economic and social status91. The thread that connects the three governors of the Moro Province was their experience in the Military. This unique factor, can be seen to influence their views and policies on education. An example of this is their view that education is a way to instill discipline and a means to solidify the relationship between the natives and government is 86 Ibid Ibid 88 Ibid 89 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1911], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1911.001. 90 Ibid 91 Pershing, John J. My Life before the World War, 1860-1917: A Memoir General of the Armies John J. Pershing. Edited by John T. Greenwood. University Press of Kentucky, 2013. 87 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 27 another view shared by all of the governors with Gen. Wood's support for the use of corporal punishment, Gen. Bliss’ use of mild-despotism, and Gen. Pershing’s incorporation of military drills in the public school. In addition, despite the initial mandate of the Moro Province to establish an education system separate from that of the rest of the country, the educational policies of these three governors mirrors that of the national educational policies of the directors of the Bureau of Education which puts importance on the industrial and agricultural education of the natives. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 28 CHAPTER 3 The Educational Diversity: Religious schools and the Emergence of Secular Public schools The Pandita educational system, as discussed in Chapter 1, is an educational system that has been part of the Muslim community in the Southern Philippines since its introduction by Arab missionaries during the 13th or 14th-century 92. Moreover, the Pandita is first and foremost an influential individual in the Filipino-Muslim Community, touted as the defender of the faith93. During the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, Jesuit missionaries in Mindanao regarded Panditas as hostile94. As the Philippine Islands changed hands from the Spanish to the Americans, the new colonizers heavily relied on the Jesuit accounts to understand the Panditas and the Filipino-Muslim community. The biased perception of the Panditas as “barbaric and uncivilized” was widely accepted by many Americans95. However, Dr. Najeeb Saleeby, an American scholar who studied the Filipino-Muslims of Mindanao and Sulu and would become the 1st Superintendent of the School of the Moro Province, deviated from this biased view of Panditas - describing them as “the scholar who can read and write and perform the functions of a priest”96. Prior to the arrival of the Americans in the late 19th century, the Pandita education system was limited to the instruction of the Islamic faith, culture, and literature97. Furthermore, unlike the public school system established by the Americans, the Pandita system was not institutionalized rather, it was conducted only through a tutoring system, without a permanent building or educational materials98. In the same manner, the parochial schools, established by Jesuit missionaries in the region, were limited to the catechismal and agricultural education99. In addition, these parochial schools are located in the coastal areas of Mindanao due to their inability to penetrate the inner lands of Mindanao100. 92 Samid, Amina H. “Islamic Education and the Development of Madrasah Schools in the Philippines.” International Journal of Political Studies 8 (August 2022): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.25272/icps.1139650. 93 Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. “The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries.” Archipel. Études Interdisciplinaires Sur Le Monde Insulindien, no. 103 (August 30, 2022): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2969. 94 Ibid 95 Ibid 96 Saleeby, Najeeb M. “Studies in Moro History, Law and Religion (Full Text).” STUDIES IN MORO HISTORY, LAW AND RELIGION (blog), September 12, 2015. https://morohistorylawandreligion.wordpress.com/studies-in-moro-history-law-and-religion-full-text/. 97 Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. “The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries.” Archipel. Études Interdisciplinaires Sur Le Monde Insulindien, no. 103 (August 30, 2022): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2969. 98 Ibid 99 Ibid 100 Moro Province. Governor. Annual Report. Zamboanga, 1908. http://archive.org/details/aaf7627.1908.001.umich.edu. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 29 The Pandita schools and the Emergence of a Secular public school As previously mentioned, the Pandita educational system has been one of the earliest educational system in Mindanao. It has been considered by some scholars as an important tool against the spread of Christianity and Spain in the region. Even with the establishment of a secularized public school by the American military government during the 10-year period of the Moro Province, the Pandita Schools remained the primary educational institution in Mindanao for Muslim Filipinos. During the early years of the Moro Province, under the governorship of Gen. Wood, he noted in his 1904 report that the Muslim population’s devotion to their faith and the Pandita system posed great challenges in convincing them to enroll in public schools101. Under the leadership of Gen. Bliss and with the aid of the Superintendent of Schools, the Pandita system was institutionalized, with new Pandita schools being established102. The Pandita schools, which were taught by panditas and Muslim educators, were still under the jurisdiction of the Governor and the Superintendent of Schools for the province. Because the traditional curriculum of Pandita schools was limited to the instruction of Arabic and Islamic literature and culture, Governor Bliss insisted on creating and procuring necessary educational supplies to supplement the education of young Muslim Filipinos. This included materials such as paper, blackboards, and most importantly, textbooks, containing subjects like arithmetic, geography, and sanitation, among others. In his 1909 report, Governor Bliss stated that it was the duty of the provincial government to ensure the educational development of students in the region, even if they were not enrolled in the public school system103. He further emphasized that supplying educational materials to these schools would provide opportunities for Filipino-Muslim parents to provide adequate education to their children104. He then requested that these educational materials, more importantly, the textbooks be created as soon as possible, in order to not hamper the educational development of the students. In addition to this, Governor Bliss stated that the aid given would only take a meager cost to the provincial government, and would bolster a positive perception of the Muslim Filipinos towards the government105. Gen. Bliss, however, lamented that these efforts 101 Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 1904. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1904], 1904. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1904.001. 103 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1909], 1909. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1909.001. 104 Ibid 105 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1909], 1909. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1909.001. 102 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 30 in improving the curriculum of the Pandita schools are not an attempt to make the Pandita schools the staple educational institution in the region and neglect the establishment and development of public schools, but rather an important entryway for Muslim Filipinos to accept the establishment of regular schools106. As the governorship of the Moro province changed hands from Gen. Bliss to Gen. Pershing in 1909, the latter continued the policies of his predecessor concerning the Pandita schools. General Pershing agreed with his predecessor that aiding these schools would be a praiseworthy effort to improve relations between the government and the Muslim-Filipino population107. During his term, he reported that in all of the districts within the province, there were both public and pandita schools. However, he emphasized that the pandita schools, though catering solely to the education of Muslim Filipinos, are still within the purview of Sir Charles R. Cameron, the Superintendent of Schools. Furthermore, he stated that the educational materials used in these pandita schools are regularly inspected to ensure that they are in line with the province’s educational standards108. In addition to this, the Supt. of schools Charles Cameron praised the Pandita schools in his published article in the February 3, 1909 issue of the Mindanao Herald. He wrote that “The Pandita schools, as they been dominated, are praiseworthy, not only for the really valuable training which they give the otherwise abandoned children, but also for the good will towards the government which they are instrumental in creating among the Moro population”, further echoing the sentiments of the governors of the Moro Province109. He further added that he supports the teaching of native languages in these schools. Also, note the positive shift in the government’s attitude towards this practice. He added that he believes that the study of native language should be supported so long as it would not hamper the effectiveness of the public school system and would promote further education110. 106 Ibid Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1911], 1911. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1911.001. 108 Ibid 109 The Mindanao Herald. The Mindanao Herald. [Vol. 6, No. 11], 1909. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aqw1509.0006.011. 110 Ibid 107 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 31 Parochial Schools and the Emergence of a Secular public school Prior to the arrival of the Americans, Jesuit missionaries have set up parochial schools in the coastal areas of Mindanao, after the Americans arrived in the Island and the subsequent departure of the Spanish Jesuit missionaries the development of Parochial schools became stagnant111. However, as reported by Governor Wood in his 1904 report during the early years of the Moro province, there was a resurgence of Parochial schools and he attributed this to the return of the Jesuit missionaries in the Province112. Similarly to how the Muslim Filipinos regarded their Pandita schools, Gov. Wood reported that the Christian population of the M.P., “...is devotedly attached to their own parochial schools”113. During the term of Gov. Wood, when Act No. 167 was passed which provides for the compulsory attendance of children in the province, a key exemption to this rule are students who were already enrolled in the Parochial schools114. Under Gov. Bliss, he reported that due to the compulsory school law, there was an increase in attendance at parochial schools115. In line with this, in the following year school year 1907-1908, he reported that due to parents transferring their children to parochial schools five public schools were closed down due to low enrollment rates116. In spite of this, Gov. Bliss was secured that as long as the educational standard in parochial schools was within the standards of the public schools, the educational development of the Christian Filipinos would not be impeded117. The reports of the Governor and the Superintendent of Schools of the Moro Province show that, despite the presence of Pandita and Parochial schools in the province, the American military government was determined to establish and develop a secularized public educational system. It must be noted that the reports of the Governor nor that of the Superintendent of Schools of the Moro Province was not able to convey the extent of the growth of these two educational institutions, but nevertheless emphasized the influence they hold in their respective communities. The actions and decisions of these three governors in aiding not only the parochial schools but also the Pandita schools demonstrate that, despite their initial perception of Panditas as uncivilized, they prioritized the educational development of the children of the Moro Province. 111 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1904], 1904. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1904.001. Ibid 113 Ibid 114 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1906], 1906. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1906.001. 115 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1907], 1907. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1907.001. 116 Moro Province. Governor. Annual Report. Zamboanga, 1908. http://archive.org/details/aaf7627.1908.001.umich.edu. 117 Ibid 112 The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 32 CONCLUSION Mindanao's educational landscape underwent profound changes from the first accounts of the Panditas in the 13th or 14th century to the continuing progress of the secularized public school system by the end of the Moro Province in 1913. Throughout the educational history of Mindanao, education has been utilized as a tool for the preservation of culture and tradition, to convert and to subdue, to pacify, and to provide educational development. The Panditas or the “traveling teachers” have sought to preserve and defend the Islamic faith through the education of their children of arab and Muslim pieces of literature and traditions. This form of education had been the dominant source of knowledge for Muslim-Filipino children for centuries. With the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Pandita system played a significant role in defending their faith and their territory from the incursions of both the Spanish crown and the Catholic church. Through the Jesuit missionaries, the Spaniards were able to establish parochial / Christian missionary schools in the coastal areas of Mindanao where the majority of the Christian Filipinos and Spaniards set up residences. With the arrival of the Americans in the early 20th century, and established military control over the region. It is during this period, that an embryonic public school system was started with the aid of Military instructors. With the establishment of the Moro Province, in June of 1903, the Public school system was influenced by the various governors of the region. Under Gen. Wood’s term, public instruction was focused on the industrial skills of its students and expediting the use of English as the language of instruction. In contrast, Gen. Bliss, despite having a similar view on the importance of industrial education for the future of both Muslim and Christian Filipinos, Gen. Bliss also saw the potential of utilizing native languages as an effective entryway to secularize education. During the term of the last governor of the Moro Province Gen. John Pershing, in addition to continuing the industrial-focused education of his predecessors, Pershing also emphasized the significance of improving agricultural education. All three governors of the Moro Province recognize the level of influence and prestige that both Pandita schools for the Muslim Filipino Community and the Parochial Schools for The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 33 the Christian Filipino Community possess in their respective communities. In line with this, most notably, Gen. Bliss stated that supporting and improving Pandita schools by providing textbooks and other educational materials will not only benefit the Muslim-Filipino community by providing quality education to their children but also serve to improve the image of the provincial government. In addition, Gen. Bliss also stated that the provincial government is amenable to the closure of public schools in favor of parochial schools so long as they can provide a similar level of education. The historical survey of the development of public education during the Moro Province through the lens of the governors of the Moro Province illustrates how proper education was viewed by these “designers of knowledge” and conveys their perception of how education must be delivered and consumed. This study, concludes that the Governors of the Moro Province saw education as means of achieving upward mobility in terms of one’s socioeconomic status. This is in line with their focus on industrial and agricultural education and their positive view on the improvement of both Pandita and Parochial Schools. Much more remains to be tackled and researched, to completely understand the full extent of the effects of the emergence of a secularized public school system in the Moro Province and in the years that followed. Such as tackling the views of Muslim students, their parents, and the community on the establishment of the public school system. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 34 Bibliography INTRODUCTION Primary Sources Government documents Langhorne, Capt. George. Annual Report. [1904], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1904.001. Langhorne, Capt. Geo. “Second Annual Report of the Governor of the Moro Province: For Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1905.” Zamboanga, Mindanao, P.I., September 1905. American Historical Collection. Rizal Library - Ateneo De Manila University. Wood, Maj. Gen. Leonard. Annual Report. [1906], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1906.001. Bliss, Tasker H. Annual Report. [1907], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1907.001. Bliss, Tasker H. Annual Report. [1908], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1908.001. Bliss, Tasker H. Annual Report. [1909], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1909.001. Pershing, John J. “Annual Report of Brigadier General John J. Pershing, U.S. Army, Governor of the Moro Province, for the Year Ending August 31, 1910.” Annual. Zamboanga, Mindanao, P.I., 1910. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. Pershing, John J. “Annual Report of Brigadier General John J. Pershing, U.S. Army, Governor of the Moro Province, for the Year Ending June 30, 1911.” Annual. Zamboanga, Mindanao, P.I., 1911. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. Pershing, John J. “Annual Report of Brigadier General John J. Pershing, U.S. Army, Governor of the Moro Province, for the the Year Ending June 30, 1912.” Annual. Zamboanga, Mindanao, P.I., 1912. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. Pershing, John J. Annual Report. [1913], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.0001.001. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 35 Taft, William Howard, Dean C. Worcester, Luke E. Wright, Henry C. Ide, and Bernard Moses. “Report of the United States Philippine Commission (1900).” Annual, November 30, 1900. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. The Board of Educational Survey. “A Survey of the Educational System of the Philippine Islands (1925).” Survey, 1925. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila Rizal Library. Saleeby, Najeeb M. “Elementary Education Should Be Given in the Mother Tongue,” March 9, 1925. Worcester, Dean C. The Philippines Past and Present. Vol. 2. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. Barrows, David Prescott. A Decade of American Government in the Philippines, 1903-1913, by David P. Barrows ..., 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ahz9396.0001.001. Atkinson, Fred Washington. The Philippine Islands, by Fred W. Atkinson., 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/abf2839.0001.001. Theobald, H.C. The Filipino Teacher’s Manual. New York and Manila: World Book Company, 1907. United States Congress, and Philippine Commission. An Act providing for the Organization and Government of the Moro Province, 787 § (1903). https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/28/37265. Secondary Sources Alip, Eufronio M. Philippine History: Political, Social, Economic. Seventh. ALIP & SONS, INC., 1958. Alzona, Encarnacion. A History of the Education in the Philippines 1565-1930. 1st ed. Manila: University of the Philippines, 1932. Charbonneau, Oliver. “Chapter 3 - Civilizational Imperatives: Building Colonial Classrooms.” In Civilizational Imperatives: Americans, Moros, and The Colonial World, 73–93. Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2021. Estioko, Leonardo R. History of Education: A Filipino Perspective, 187-197. LOGOS Publications, Inc., 1994. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 36 Isidro, Antonio. “Education of the Muslims.” In The Muslim Filipinos: Their History, Society, and Contemporary Problems, 272–73. 531 Padre Faura, Ermita, Manila, Philippines: Solidaridad Publishing House, 1974. Martin, Dalmacio, ed. “Chapter IV: Philippine-American Educational Partnership, 1898-1935.” In A Century of Education in the Philippines 1861-1961, 165–97. Manila: Philippine Historical Association, 1980. May, Glenn Antony. Social Engineering in the Philippines: The Aims, Execution, and Impact of American Colonial Policy, 1900-1913, 1980. Peter Gordon Gowing, Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920. Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. New York: New York : Knopf, 1993. Constantino, Renato. “The Miseducation of the Filipino.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 1, no. 1 (1970). chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://nonlinearhistorynut.fil es.wordpress.com/2010/02/miseducation-of-a-filipino.pdf. Other Sources: Childhope Philippines Foundation, Inc. “Education Issues in the Philippines: The Ongoing Struggle,” August 25, 2021. https://childhope.org.ph/education-issues-in-the-philippines/. Mohr, John, and Marc Ventresca. “Archival Research Methods,” 805–28, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405164061.ch35. CHAPTER 1 Alzona, Encarnacion. 1932. A History of the Education in the Philippines 1565-1930. 1st ed. Manila: University of the Philippines. Arcilla, Jose S. 1978. “The Return of the Jesuits to Mindanao.” Philippine Studies 26 (1/2): 16–34. Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. “The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries.” Archipel. Études Interdisciplinaires Sur Le Monde Insulindien, no. 103 (August 30, 2022): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2969. Charbonneau, Oliver. “Chapter 3 - Civilizational Imperatives: Building Colonial Classrooms.” In Civilizational Imperatives: Americans, Moros, and The Colonial World, 73–93. Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2021. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 37 Forbes, W. Cameron. The Philippine Islands I. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1928. Foreman, John. The Philippine Islands: A Political, Geographical, Ethnogrpahical, Social and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago. Third. Filipiniana Book Guild, 1906. Gowing, Peter G. Mandate in Moroloand: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920. New Day Publishers, 1983. Guerrico, Jose Ignacio. Letter to Mission Superior. “Jesuit Missionary Letters from Mindanao: Jose Ignacio Guerrico to the Mission Superior,” 1875. Rizal Library - Ateneo De Manila University. Harrison, Francis Burton. The Corner-Stone of Philippine Independence: A Narrative of Seven Years. New York: The Century Co., 1922. Kulidtod, Zainal Dimaukom. “ISLAMIC EDUCATIONAL POLICIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: ITS EVOLUTION AND CURRENT PROBLEMS.” International Research-Based Education Journal 1, no. 1 (May 29, 2017). https://doi.org/10.17977/um043v1i1p%p. Lantong, Abdul M. “The Islamic Epistemology and Its Implications for Education of Muslims in the Philippines,” 67–71. Atlantis Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2991/icigr-17.2018.16. Milligan, Jeffrey Ayala. Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. Samid, Amina H. “Islamic Education and the Development of Madrasah Schools in the Philippines.” International Journal of Political Studies 8 (August 2022): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.25272/icps.1139650. Solaiman, Saddam Mangodato. “Implementation of Arabic Language and Islamic Values Education (ALIVE) in Marawi City, Philippines: Unveiling the Perceptions of ALIVE Teachers.” Education Journal 6, no. 1 (February 10, 2017): 38. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.edu.20170601.15. CHAPTER 2: Primary Sources: Bliss, Tasker H. “The Government of the Moro Province and Its Problems.” The Mindanao Herald Publishing Company. February 3, 1909. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 38 Davis, George. “Annual Report of Major General W. Davis 1903.” Annual. Manila: War Department, October 1, 1902. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila Rizal Library. Davis, George. “General Davis’s Report on Moro Affairs.” Manila: War Department, October 24, 1901. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. Febiger, Commander Lea. “Report Commanding Officer, Cotabato.” Zamboanga, Mindanao, P.I., June 4, 1902. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila Rizal Library. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1905], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1905.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1906], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1906.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1907], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1907.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1909], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1909.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1910], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1910.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1911], 2005. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1911.001. Pershing, John J. My Life before the World War, 1860-1917: A Memoir General of the Armies John J. Pershing. Edited by John T. Greenwood. University Press of Kentucky, 2013. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 39 The Board of Educational Survey. “A Survey of the Educational System of the Philippine Islands (1925).” Survey, 1925. American Historical Collection. Ateneo De Manila - Rizal Library. United States Congress, and Philippine Commission. Act No. 787 - AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE ORGANIZATION AND GOVERNMENT OF THE MORO PROVINCE. - Supreme Court E-Library, Pub. L. No. Act No. 787 (1903). https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/28/37265. Secondary Sources: Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Leonard Wood | United States General | Britannica.” Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leonard-Wood. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Tasker Howard Bliss | United States Military Leader | Britannica,” January 11, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tasker-Howard-Bliss. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “John J. (Black Jack) Pershing | Biography, Facts, & Nickname | Britannica,” January 22, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-J-Pershing. Gowing, Peter G. “Chapter Eight: John J. Pershing: The End of the Moro Province, 1909-1913.” In Mandate in Moroloand: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos 1899-1920, 212–18. New Day Publishers, 1983. Wood, Eric Fisher. “Chapter XIII: Governor of the Moro Province.” In Leonard Wood: Conservator of Americanism, 216–36. New York: George H. Doran Company, 1920. CHAPTER 3: Primary Sources: Education, Philippines Bureau of. Annual Report. [1904], 1904. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acs9512.1904.001. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 40 Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [Vol. 1, No. 1], 1903. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.0001.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1904], 1904. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1904.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1905], 1905. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1905.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1906], 1906. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1906.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1907], 1907. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1907.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1909], 1909. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1909.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1910], 1910. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1910.001. Governor, Moro Province. Annual Report. [1911], 1911. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aaf7627.1911.001. Moro Province. Governor. Annual Report. Zamboanga, 1908. http://archive.org/details/aaf7627.1908.001.umich.edu. Saleeby, Najeeb M. “Studies in Moro History, Law and Religion (Full Text).” STUDIES IN MORO HISTORY, LAW AND RELIGION (blog), September 12, 2015. https://morohistorylawandreligion.wordpress.com/studies-in-moro-history-law-andreligion-full-text/. The Mindanao Herald. The Mindanao Herald. [Vol. 6, No. 11], 1909. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/aqw1509.0006.011. Secondary Sources: Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. “The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th - Early 20th Centuries.” Archipel. Études Interdisciplinaires Sur Le Monde Insulindien, no. 103 (August 30, 2022): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2969. The Bumpy Road towards Enlightenment 41 Guleng, Marlon Pontino, Razaleigh Muhamat@Kawangit, and Zulkefli Aini. “Issues on Islamic Education in the Philippines: Isu-Isu Pendidikan Islam Di Filipina.” Al-Irsyad: Journal of Islamic and Contemporary Issues 2, no. 1 (June 20, 2017): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.53840/alirsyad.v2i1.22. Samid, Amina H. “Islamic Education and the Development of Madrasah Schools in the Philippines.” International Journal of Political Studies 8 (August 2022): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.25272/icps.1139650.