Cyberstalking Literature Review: Analysis & Future Research

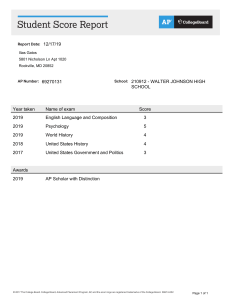

advertisement