Stability of a Unipolar World: US Power & International Relations

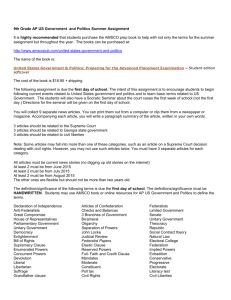

advertisement