Collective & Transgenerational Trauma in Conflict Transformation

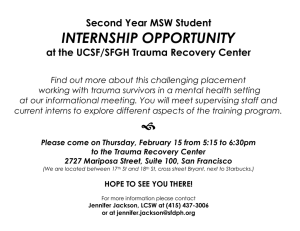

advertisement