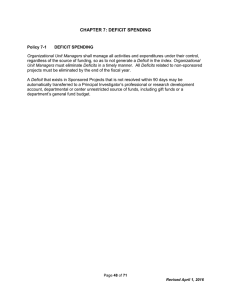

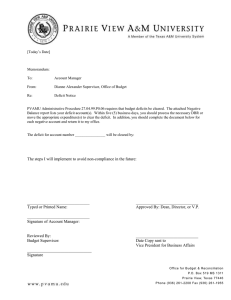

How to Solve the U.S.-Japan Trade Problem Author(s): DOMINICK SALVATORE Source: Challenge , JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1991, Vol. 34, No. 1 (JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1991), pp. 40-46 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40721224 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Challenge This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms DOMINICK SALVATORE How to Solve the US. -Japan Trade Problem In a world of imperfect competition and all sorts of market failures, strategic trade can improve on the free-trade solution and enhance U.S. global industrial competitiveness. The United States now has a trade deficit with practically Japan's all of its major trade partners. While trade need not, of trade pattern The U.S. bilateral merchandise trade deficit with Japan course, be balanced bilaterally with each country, the U.S. increased from about $4 billion in 1972 to a high of trade deficit with Japan has grown so large and persistent, even with its modest decline in recent years, that the nearly United $60 billion in 1987, before falling to nearly $56 States can be said to have a specific trade problembillion with in 1988 and $50 billion in 1989 (Table 1). As a percentage of the U.S. overall total trade deficit, our Japan. Moreover, during the past decade or so, the United States has lost competitiveness with respect to Japan bilateral in one trade deficit with Japan ranged from nearly 30 percent in 1984 to nearly 46 percent in 1981, and it was industry after another. There are now only a few high-tech over 43 percent in 1989. Thus, Japan, singlehandedly, is industries in which the United States retains undisputed now responsible for over 40 percent of our overall trade leadership over Japan. But even in these, Japan is gaining deficit fast and may surpass the United States by the turn of the and this ratio has increased sharply since 1984. An examination of the distribution of the overall U.S. century in the absence of corrective action. Thus, the U.S.Japan trade problem has two interrelated aspects: trade deficit among its major trade partners shows the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with Japan in 1989 to be (1) The bilateral deficit with Japan is a dis$49.8 billion. This was nearly four times larger than our proportionately large part of the overall, or macroecosecond largest trade deficit (with Taiwan), and more than five times larger than our third and the fourth (2) The changing composition of U.S.-Japan trade nomic, trade deficit. largest trade deficits (with Canada and Germany). Inreflects a growing loss of U.S. technological competideed, the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with Japan in 1989 tiveness at the microeconomic level. DOMINICK SALVATORE is Director of the Graduate Program and Professor of Economics at Fordham University, New York. This article is adapted from the author's study conducted for the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. 40 Challenge/January-February 1991 This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Table 1 U.S.-Japan Bilateral Merchandise Table 3 Import Penetration Ratios in Trade and Trade Balance Manufacturing, 1975, 1985 and 1986 (imports as percentage of apparent consumption*) (in billions of U.S. dollars) Imports From: United States Germany Japan Percentage of Exports Imports Trade Balance Total U.S. Trade Year 1972 5.0 1976 10.2 1980 20.8 1981 21.8 1982 21.0 1983 21.9 1984 23.6 9.1 -4.1 43.2 15.5 -5.3 31.0 33.0 -12.2 33.7 39.9 -18.1 45.7 39.9 -18.9 44.4 43.6 -21.7 31.3 60.4 -36.8 29.8 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 72.4 85.5 88.1 93.2 93.5 22.6 26.9 28.2 37.7 43.7 Source: IMF, -49.8 -58.6 -59.9 -55.5 -49.8 33.5 34.5 34.5 40.2 43.3 Direction World 1975 7.0 24.3 1985 12.9 39.5 1986 13.8 37.2 4.9 5.4 4.4 O.E.C.D. 1975 1985 1986 2.9 3.2 2.6 4.9 8.8 9.3 20.5 32.5 30.6 Developing 1975 1985 1986 of 2.1 3.9 4.2 2.6 4.5 4.4 Countries 1.8 2.0 1.8 ♦Apparent consumpti Trade Statistics, Washington, D.C exports. Source: Advisory Committee for Trade Policy Negotiations, Analysis of the US. -Japan Trade Problem, Washington, D.C, February 1989, p. 10. Table 2 U.S. Bilateral Trade Balances (in billions of U.S. dollars) for Japan. The ratio for imports from developing coun- Area Japan -12.2 -49.8 -58.6 -59.9 -55.5 -49.8 E.C.C. 18.9 -22.6 -26.3 -24.3 -12.8 -0.9 Germany -1.3 -12.2 -15.5 -16.3 -13.1 -8.3 France 2.O -3.9 -3.4 -3.3 -2.6 -1.3 U.K. 2.4 -4.3 -4.6 -3.9 -0.3 2.4 Italy 0.8 -5.8 -6.5 -6.2 -5.5 -4.8 Canada -6.6 -22.1 -23.4 -14.1 -12.2 -9.7 Brazil 0.4 -5.0 -3.4 -4.4 -5.7 -3.7 Mexico 2.3 -5.9 -5.2 -5.9 -2.9 -2.4 Taiwan -2.8 -11.2 -14.6 -17.5 -13.0 -13.3 Korea 0.3 -4.7 -7.1 -9.9 -9.9 -6.7 Hong-Kong -2.3 -6.2 -6.3 -6.5 -5.1 -3.4 Singapore 1.0 -0.9 -1.5 -2.3 -2.5 -1.6 Oil Exporting United States, from 20.5 percent to 30.6 percent for Germany, but declined from 2.9 percent to 2.6 percent Country or Countries -40.2 -9.6 -9.3 -13.6 -10.2 -6.6 tries rose from 2.1 percent to 4.2 percent for the United States, from 2.6 percent to 4.4 percent for Germany, but remained unchanged at 1.8 percent for Japan. In the past, Japan' s low import ratios for manufactures has been explained by its relative resource-poor economic base, by its geographical distance from other world markets, and its other economic attributes. More recently, however, Japan's imports of all goods were estimated to be between 25 percent and 45 percent lower than they should be, based on the usual criteria of indus- trial structure, size, and level of economic development. In addition, the prices of traded goods in Japan are estimated to be 86 percent higher on average than in the United States. Without trade barriers, international arbi- Source: IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics, Washington, D.C. tration - the purchasing of goods where they are cheaper and reselling them for a profit where they are more - would have essentially eliminated internawas larger than the sum of all the other expensive ten trade deficits shown in Table 2. tional price differences in the two nations (except for Between 1975 and 1986, the average transportation import penetracosts). international tion of the U.S. market for manufactured Thus, goods from price all comparisons strongly sugcountries rose from 7.0 percent to 13.8 in the high trade barriers that gest percent that Japan has relatively United States. Table 3 shows this penetration effectively rising restrictfrom imports of manufactured goods. Indeed, 1989 Reportwith of the Advisory Committee for 24.3 percent to 37.2 percent for Germany (athe country Trade Policy Negotiations (see For Further Reading) an economic structure similar to Japan's), but itand actually "In summary, in the response to the quesdeclined from 4.9 percent to 4.4 percentconcludes, in Japan. For the tion, manufactured 'Is there anything different about Japan's pattern of same years, the import penetration for especially manufactured trade?' the studies [regoods from the twenty-four member trade, countries of the viewed] suggest the answer is an unqualified yes." (See Organization for Economic Cooperation and Developespecially, Alan Blinder in For Further Reading.) ment (OECD) rose from 4.9 percent to 9.3 percent for the January -February 1991 /Challenge 41 This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Table 4 Changing Composition of U.S. Trade in High-Tech Manufactured Goods with Japan (in billions of U.S. dollars) 1972 0.3 0.5 1976 0.4 1.0 1980 0.9 2.5 1985 1.8 9.9 1986 2.0 11.6 1987 2.6 13.9 -0.2 -0.6 -0.6 -0.8 -1.6 -1.1 -8.1 -5.5 -9.6 -6.2 -11.3 -6.3 1988 -13.1 3.7 16.8 -5.7 -0.4 -0.5 -0.8 -3.8 -4.5 -4.6 -4.1 Machine Tools 1972 0.3 0.3 -0.0 1976 0.5 0.8 -0.3 -0.4 1980 0.9 2.3 -1.4 -1.0 1985 1.0 5.7 -4.7 -3.2 1986 0.9 6.7 -5.8 -3.7 1987 0.9 7.5 -6.6 -3.7 1988 1.5 8.4 -6.9 -3.0 Other -0.3 -0.7 -2.2 -2.7 -2.7 -2.2 Machinery an Exports Imports Trade Balance TB as % of TME TB as % of TE 1972 1976 1980 1985 1986 1987 1988 0.8 0.9 2.3 3.2 3.8 4.3 5.4 1.1 1.7 3.6 7.5 9.1 10.6 12.7 -0.3 -0.8 -1.3 -4.3 -5.3 -6.3 -7.3 -0.9 -1.1 -0.9 -2.9 -3.4 -3.5 -3.2 Total -0.6 -0.7 -0.6 -2.0 -2.5 -2.6 -2.3 Engineering Exports Imports Trade Balance TB as % of TME TB as % of TE 1972 1.4 5.6 -4.2 -12.7 -8.8 1976 2.0 10.7 -8.7 -11.6 -7.9 1980 4.4 24.8 -20.4 -14.6 -9.6 1985 6.4 59.0 -52.6 -35.4 -24.9 1986 7.1 72.0 -64.9 -41.6 -30.2 1987 8.2 74.2 -66.0 -36.8 -27.1 1988 11.4 77.7 -66.3 -28.6 -20.7 TB=trade balance; TME=total Source: GATT, International The U.S. microeconomic trade manu Trade parts and engines. The first three classifications include all the suppliers (as opposed to the users) of high technology and are of particular relevance in evaluating the change in the competitive position of the United States While the size and growth of our overall bilateral trade vis-à-vis Japan during the past two decades. deficit with Japan is certainly a major problem for the problem with Japan United States, it is Japan's trade and industrial practices From Table 4, we see that while our competitive position deteriorated throughout the 1972-1988 period, at the microeconomic or industry level that are potentially that deterioration rose to truly massive proportions from more dangerous to our future well-being. The commodity 1980 to 1985. In five short years, the United States develcomposition of U.S. trade with Japan changed significantly from 1972 to 1988 in: (1) office and telecommuni-oped a very large trade deficit with Japan in all these high-tech sectors both in absolute and relative terms. cations equipment; (2) machine tools; (3) other From 1980 to 1985, our bilateral trade deficit with Japan machinery, such as power generating machinery, and increased from $1.6 billion to $8.1 billion in office and transport equipment like railway vehicles and aircraft; telecommunications equipment, from $ 1 .4 billion to $4.7 and (4) engineering products, which include all of the billion in machine tools, from $1.3 billion to $4.3 billion above categories as well as automobiles and automobile 42 Challenge/January -February 1991 This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms in other machinery and transport equipment, and from $20.4 billion to $52.6 billion for all engineering products combined. Our bilateral trade deficit with Japan increased from 14.6 percent to 35.4 percent of total U.S. manufactured exports to all nations and from 9.6 percent Japan s unique strategies for conquering new industries While mature and high-tech U.S. industry lost compet- to 24.9 percent of all total U.S. exports. itive ground by taking a short-term view of profits, Japan was implementing trade and industrial policies The U.S. short-term view of profit strategy for conquering a new industry is by now clear, that seriously eroded U.S. competitiveness. Japan's This dramatic decline in U.S. competitiveness is our having been successfully applied to a number of industries from steel and automobiles to semiconductors and own fault in some ways. Firms in some U.S. industries, robots. especially automobile and steel, became sluggish after World War II. They enjoyed vast technological superi- imports and foreign investments in the industry, coor- ority after the war, they operated in a large and unified dinates the acquisition of technology abroad, and pro- In the first stage of this strategy, Japan restricts domestic market, and they were sheltered from foreign vides subsidies and tax advantages to master and competition to some extent by two vast oceans. U.S. steel producers failed to adopt new technology quickly, and U.S. automakers failed to improve product quality introduce the new technology in the targeted industry. as rapidly as Japanese producers, and both paid excessive attention to short-run profits rather then long-term growth prospects. Both industries were also hurt by the In the next stage, the government coordinates a massive expansion of industrial capacity, facilitated by large availability and low cost of capital. In the third stage, the industry invades the world market, originally accepting very low profits or even losses while high value of the dollar during most of the 1980s, at the acquiring market share and continuing to improve same time that Japanese producers were reaping the technology and product quality. In the fourth and final stage, foreign countries, facing the prospect of demise benefits of previous strategic governmental support for these same industries (see Gene M. Grossman in For of a major industry, restrict Japanese access to their Further Reading). markets, often with voluntary export restraints, which The decline of U.S. competitiveness in high-tech industries, especially semiconductors, occurred for different reasons. Most U.S. producers in semiconductors were relatively small, sold only computer grant substantial market share and ensure high prices and profits for Japanese firms. By this time, Japan has dismantled its own formal import restrictions in the targeted industry and asserts its belief in free trade. chips, and generally took a short-run view of profits. Furthermore, their technology could easily be reverse- Japan has targeted the computer industry for the 1980s engineered and copied, and they lacked the resources to defend it effectively in protracted and costly legal battles. Lack of resources prevented their expanding at home and precluded their selling or establishing the 1990s. Without adequate American response, his- production facilities abroad, especially in Japan. Often these firms sold or licensed their technology to Japanese firms in order to increase short-term revenues and profits. Consequently, in the long run the U.S. semiconductor firms were unable to compete with their much larger and vertically integrated Jap- anese competitors. The latter took a long-term view. They were able to sustain large and even prolonged losses in their semiconductors line from profits earned in their many other lines of business. The United States thus squandered its leadership position in an industry that only a few years earlier had been the pride of U.S. advanced technology and the envy of the entire world, including Japan. and the commercial aircraft and space industries for tory is likely to repeat itself. While not all targeting efforts of Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) have been successful and not all have operated as intended, MITI was crucial in contributing to Japan's stunning competitiveness and trade successes. The consensus of expert opinion cited in the conclusion of the 1989 Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations holds that MITI used administrative guidance, import restrictions, coordination of investment in plant and equipment, merger and other methods of production consolidation, approval of cartels, postponing of liberalization of direct investment from outside, tax incentives for leading indus- tries, lower interest loans, and other measures. . . . The argument that the financial contribution made by the Japanese government is not a huge sum provides us with little comfort because of the profound impact the organization of research projects could have on the timing of January -February 1991 /Challenge 43 This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms innovation, on patterns of interfirm competition and co- operation, and on industrial structure. . . . (See Bela B alassa and Marcus Noland in For Further Reading.) Several of MTITs strategies and policies have been particularly effective. MITI fosters competition at home by simultaneously promoting several domestic firms in targeted industries and encouraging exports at an early stage. If foreign companies apply for a crucial patent that gives them an important competitive advantage, MITI industrial targeting were as important as domestic shortcomings. Dangers arising from Japan's trade and industrial policies The sharp decline in U.S. competitiveness in high-technology products in relation to Japan seriously endangers the future well-being of the United States. That decline delays awarding the patent until Japanese producers have is intrinsically more dangerous than our large overall a chance to catch up or apply for patents to cover similar trade deficit with the rest of the world and with Japan, technology. It takes six years to register a patent in Japan (as compared with two years in the United States and one serious as those are. Indeed, one could well imagine a situation in which the United States had no bilateral trade year in the United Kingdom) and during this time the deficit with Japan, but where most U.S. imports from foreign firm is very vulnerable to unauthorized copying Japan consisted of leading-edge technological products of its invention by Japanese firms. while our exports consisted mostly of agricultural prod- There is more specific evidence that Japan effec- ucts and raw materials. Since most of the growth in tively restricts entry into its market directly or through productivity and the standard of living depends on the its unique distribution system and buyer preferences. introduction of advanced technology, a continued deteri- For example, during the 1970s and early 1980s U.S. oration in the U.S. competitive position is ominous. It semi-conductors and telecommunications firms held could only foreshadow an accelerating trend of slower growth and decline in our standard of living in relation to less than 10 percent and 3 percent, respectively, of the Japan, and perhaps even in relation to the countries of Japanese market at a time when they dominated the world market and were the undisputed technologicalWestern Europe, as well as to the newly industrializing countries. This rather gloomy scenario cannot be disleaders. Impartial observers readily admit that Japan is informally highly protectionistic. The Office of the U.S.missed out of hand. Another five or ten years of deterio- Trade Representative (1990) lists more than twice as ration in the trade and competitiveness position of the many formal and informal trade barriers against U.S.United States of the same order of magnitude as that exports for Japan than by the entire European Economicwhich occurred from 1980 to 1985, and the United States Community. The United States today supplies only 6could potentially lose its ability to compete effectively in most high-technology products with Japan, and in some percent of the supercomputers bought by Japan's goveven with Western Europe. ernment and publicly financed universities, although The rapid and sharp deterioration of our semiconducwe hold an 80 percent share of the world market. From all of the above, we can safely conclude that:tor industry as a result of Japanese competition has (1) Japan does effectively restrict entry into its mar-ominous implications for the future competitive position ket either directly or through its unique distributionof almost all high-technology industries in the United States. "Downstream industries' ' (industries using comsystem and buyer preferences. (2) Japan does target industries. While there is dis-puter chips) are much larger than the semiconductor agreement on the effectiveness of such policies and how industry itself and produce the bulk of U.S. exports. As much of Japan's stunning competitiveness and tradepointed out by the 1989 MIT study Made In America (p. successes can be attributed to targeting, evidence is 26), ' 'American computer makers now obtain more than mounting that industrial targeting was crucial to Japan ' shalf of their semiconductors from Japan . . . from the same rapid rise to a high-technology leadership position. diversified companies that are their competitors in the (3) The cause of the U.S. competitiveness and tradecomputer market. (See Michael L. Dertouzos in For problems with Japan lies with both the United StatesFurther Reading.) By withholding or delaying making its and Japan. In many high-tech sectors, such as computcomputer chips available to competing U.S. firms, the ers and telecommunications, in which the United States Japanese could also seriously affect the United States was and is the world leader, as well as in some mature lead in computers. The Office of Technology Assessment industries earlier when the United States was more of the U.S. Congress (1989:iii) pointed out another omi- competitive, Japan's restrictive distribution system and nous implication: "Foreign companies have made deep 44 Challenge/January-February 1991 This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms inroads into high-technology markets that had been more or less the exclusive domain of U.S. industry. In addition market-opening measures would cut our global trade deficit during the 1990s in general and bilateral trade when the technology in defense systems comes increas- deficit with Japan (the latter cut by only about $11 billion), they are absolutely essential for reducing the U.S. competitive and trade disadvantage and for estab- ingly from the civilian sector." lishing 4 * a level playing field' ' with respect to Japan. That to causing economic problems, this has fostered dependence on foreign sources for defense equipment at a time still leaves nearly a $40 billion deficit in U.S. trade, even if the appropriate macroeconomic policy coordination Solving U.S. trade and competitiveness problems with Japan and the market-opening trade measures work effectively. Various policies are being or could be used to reduce sharply or eliminate the large U.S. overall and bilateral necessity for the United States to adopt further competitiveness measures. trade deficits, and to overcome the serious U.S. compet- The still large deficit remaining only underscores the A growing number of people in the United States doubt itiveness problem with Japan. These include depreciating that much can be accomplished by multilateral or bilateral the dollar further, cutting the U.S. budget deficit, coordi- market-opening negotiation, the present effort included, nating international policy, and opening up foreign mar- especially when it comes to Japan. They point out that kets, along with other competitiveness measures. too many times in the past, after strenuous and protracted William R. Cline has offered a comprehensive and negotiations, touted success has turned out to be ephem- elaborate plan for reducing the U.S. overall and bilateral eral. It may be, as some hold, that no interest group in trade deficits with Japan (see For Further Reading). His Japan has the power or political will to bring about plan calls for the gradual elimination of the U.S. budget significant change along these lines, even if it wanted to. deficit, the stimulation of domestic demand in Japan and The United States, of course, has itself many trade Germany, and a moderate trade- weighted depreciation of restrictions against Japanese exports. But these were for the dollar. According to his estimates, reducing the U.S. the most part imposed in response to Japanese strategic budget deficit would eliminate one-third of our trade trade practices and only after Japan had gained a signifi- deficit by 1992, while another third would be eliminated cant market share in a major U.S. market. For example, by the combined effect of the expansion of domestic demand in strong currency countries and the trade- Japan has captured 34 percent of the automobile market weighted devaluation of the dollar. Cline feels that any United States has less than 3 percent of the Japanese market stronger policy action would not be feasible. His plan would still leave a U.S. trade deficit of about $50 billion computers despite the greater efficiency of U.S. firms. by 1992, of which $30 billion would be with Japan. Cline's proposal, however, implicitly assumes a degree of international policy coordination among the United through exports and production by transplants, while the in telecommunications and only about 6 percent in super- Pessimism is growing about the ability of the United the different inflation tradeoff in each country. Even if States to solve its overall and bilateral trade problems through multilateral and bilateral market-opening trade negotiations. Advocates of managed trade are increasingly numerous; they include Rudiger Dornbusch and the plan were fully implemented, our trade deficit would Lawrence Summers as well as former Secretaries of States, Japan, and Germany that is unrealistic because of remain large, especially with Japan. More importantly, State Kissinger and Vance. Their strategy holds that the the plan does not address (indeed, it does not even recog- United States would negotiate a planned reduction in nize) the serious U.S. competitiveness and trade problem U.S. trade deficits over the next few years with its most with Japan. Clearly, cuts in the U.S. budget deficit must be supplemented by still other policy tools. significant creditor nations. Dornbusch flatly states, "Japan must increase imports of manufactured goods from the United States at an average rate of at least 15 What about market-opening percent per year, with adjustments for inflation in each country." Further, Japanese access to the U.S. market should be cut with an automatic tariff surcharge. One method of supplementing U.S. budget deficit cuts to Most economists, however, oppose quantitative con- trade measures? reduce our trade deficits is to negotiate forcefully with trols or targets and thus reject managed trade on principle other countries (especially Japan) to open their marketsbecause it replaces the market. General targets would also more widely to U.S. manufactured exports. While these fail to deal adequately with the serious U.S. microeconomic January-February 1991 ¡Challenge 45 This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms competitiveness problem with Japan. With such a policy, these efforts. The United States should consider, however, the United States could conceivably correct its overall trade under what circumstances it should step in and provide deficit by exporting more traditional and agricultural prod- seed money, change tax and antitrust regulations, and ucts, while at the same time relying more and more on grant temporary trade protection in order to promote the es- imports of high-tech products. Furthermore, the composi- tablishment or the survival of aparticularly crucial industry. tion of U.S. exports would be decided by our competitors. It is true that a wrong policy response on the part of the An alternative to managing trade with Japan would be United States could turn out to be worse than no response for the United States to impose a temporary multilateral at all. But a strategic response is needed that would allow import surcharge of, say, 15 percent on manufactured products. While this would not increase United States access to the United States to recapture most or all of the loss, and the Japanese market, it would protect our industries from moves of its own in the future. While it is very difficult to targeted and strategic Japanese competition, and thus help devise and enact such policies and the potential for large keep them competitive on world markets. These import sur- losses and abuses exists, one cannot reject strategic com- charges could also be used as a bargaining tool to pry open petitiveness policies outright simply because the risks of Japanese markets to U.S. high-tech exports. To achieve large potential losses are very great. It may not even be a possibly even initiate some strategic and preventive effectivity and avoid breaking GATT rules, however, such question of choice. The United States may be forced by import surcharges would have to meet two conditions. First, other nations, especially Japan, to respond strategically. they would have to be multilateral rather than imposed only Put bluntly, once the genie is out of the bottle, it is both on Japanese manufactured exports to the United States. theoretically and realistically impossible to put it back in. Otherwise, Japanese firms could shift production abroad In other words, strategic trade has demonstrated that it and avoid the surcharge. Second, they would have to be applied on imports of manufactured consumer goods such can improve on the free trade solution in a world of imperfect competition and all sorts of market failures. as automobiles and office equipment, for which good do- Defenders of free trade therefore can no longer ignore the mestic substitutes are readily available. They could not be beneficial consequences of a strategic response. levied on industrial parts and components such as computer chips that are no longer produced by the United States, because they would then only reduce the international competitiveness position of our own firms using them. The New from M. E. Sharpe, Inc. import surcharge could be phased out as Japan and other countries open their markets and allow more U.S. high-tech exports, and as our bilateral trade deficit with Japan is significantly reduced. The United States, however, cannot blame all of its competitiveness problems on Japan. Indeed, part of the problem is that the United States has been falling behind Japan in such areas as education, the commercialization of new technology, and industrial cooperation. Encour- aging basic research and improving education and job training are generally accepted and noncontroversial pol- icies we must implement to overcome our deteriorating competitiveness. Other policies which involve providing trade protection to an industry in trouble are surrounded by great controversy. One particularly controversial policy is for the government to sponsor and contribute fund- ing for research and development consortia in crucial high-tech fields in order to counter foreign targeting and The Changing Face of Fiscal Federalism Thomas R. Swartz and John E. Peck, editors This volume brings together seven of the nation's most influ- ential economists, political scientists, and sociologists on the subject of U.S. fiscal federalism, its evolution from the past, and prospects for the future. The essays outline the historical and philosophical foundations of our system of governmental finances, from the first revenue sharing ideas of Henry Clay in the 1 820s, through the developing momen- tum of the federal program of revenue sharing during the Kennedy-Johnson administration and Nixon's new federalism. The book examines the radical shift in the U.S. system of fiscal federalism under Ronald Reagan, whose administration ushered in new ideology that required "separation of powers," "devolution of responsibilities to governments that are closer to the people," and "less spending by all levels of government." 224 pp. ISBN 0-87332-664-4 Hardcover $39.95 ISBN 0-87332-665-2 Paper $16.95 meet foreign competition. This kind of policy is common in Japan and Europe and is credited with giving foreign companies an edge over U.S. competitors. This does not mean that the United States should necessarily match ¿TW. E Sharpe inc. 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504 46 Challenge/January-February 1991 This content downloaded from 176.226.134.158 on Wed, 05 Jul 2023 15:49:47 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms