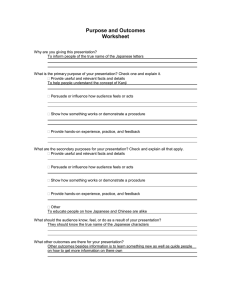

A Year to Learn Japanese Table of Contents 3. Foreword 4. Start Here: One Page of TL;DR 6. Introduction 7. How long does it take to learn Japanese? Why learn Japanese? 8. About this document, about me 9. How to use this document 10. Some closing words 11. Stages of Language Acquisition 12. Stage One: Building a Foundation 13. Phonetics 23. Kana 26. Kanji 39. Grammar 50. Vocabulary 65: Stage Two: Immersion 67: Input 91: Output 104: Interviews 105: Idahosa Ness on Pronunciation 111: Matt vs Japan on Pitch Accent, Kanji and The Journey 123: Brain Rak on Making a Career Out of Japanese 131: Appendix 132: On Learning: Further reading to help you learn more efficiently 138: On Meditation 140: My learning schedule 142: On using the MIA Japanese Addon to generate pitch accent info [step-by-step screenshots] 156: Anecdotes & Reflections (WIP) 159: Administrative Stuff 159: Links (aka cool stuff I want to include at some point) 162: Changelog 164: To-Do List 165: Thanks 166: A Request for Feedback ** Please go to view > show document outline. The document will be much easier to navigate. Page 1 Page 2 Foreword Hey there! I’m u/SuikaCider and, two odd years ago, I responded to a post by a guy who said he had a year to learn Japanese. This was actually my first post to Reddit and, unsure what to expect, I wrote a much longer reply than was necessary. Wordy as it was, the post was quite well received. I’ve since gotten several dozen messages from people seeking clarifications or asking questions that were beyond the scope of my original post. I’ve kept track of these (here), and it eventually became so chaotic that I decided to organize it. That in mind, I’ve got a couple goals with this document. ● ● ● ● I’d like to replace the old sticky with one that’s easier to follow I’d like to include reflections on learning, both about language and in general I’d like to expand the scope of the original post to include questions I’ve since gotten I’d like to reach out to people who learn languages for reasons beside reading, hopefully making this document relevant to a wider audience. Page 3 Quickstart Guide / TL;DR In its current form, this document is more a collection of landing pages for different topics in language learning than a timeline. Please skip around to suit your own needs and interests. A lot of learning is just stumbling into something important and recognizing it as such. Check out how this professional drummer listens to a song for the first time - he’s constantly noticing stuff, making connections and practical observations. Experienced learners have a good idea of what they’re looking for and where to find it; you’ve got to figure it out as you go. My goal is to help you with that. This entire document boils down to a few relatively straightforward steps. Below is a plan based on the resources I personally used, for brevity, but I offer alternatives to everything listed here in the relevant section of the document. I’ve also tried to explain who each resource would be good for. 1. A few guiding bits of food for thought a. My 4 key bits of advice: Zipf's Law, The 50% Rule, How to Learn, Music School b. Language isn’t math: You don’t magically become fluent after memorizing enough words or grammar points. Real content isn’t a sterile vacuum like a flashcard; you’ll encounter sentences you don’t understand despite knowing every word. c. If consistency isn’t your strong point, learn about habit triggers and build a trigger-action plan to ensure you work time for Japanese into your daily life. d. If you’ve already got a routine but want to optimize it, see the appendix on learning 2. First, get a feel for the lay of the land. We’re aiming to make the foreign more familiar. a. Consider investing in pronunciation: Everything you will ever do in Japanese rests on the pedestal that is pronunciation. That being said, building a pedestal is an investment. If you don’t care about sounding foreign, it might not be worth it for you. That’s OK. b. Cover the kana: Japanese has three "alphabets". First learn the kana (hiragana and katakana) on Read the Kanji's website. You'll commit them to memory by engaging with Japanese over time, so treat this only as a crash course. Being efficient > being busy. 3. Next, establish a foundation. We’ll take six months* to gather resources for Stage Two. a. The 50% Rule: Pick a regular time (whether daily, weekly or monthly) to sit down with actual Japanese content—an anime, a book, something on YouTube. Anything. Just check in. Eventually, you’ll find you can sort of work through it. Boom! Nope Threshold cleared. This is an insurance policy that guarantees you don’t spend too much time on step 3. b. Skim through grammar: Start working through Genki I, Genki II and their workbooks. If you do one grammar point per day, it’ll take about 6 months to finish both textbooks. Page 4 c. Get acquainted with Kanji. I used Heisig’s Remembering the Kanji with a structured-repetition system called Anki, but there are many viable approaches. Start with 5 per day, then gradually increase that number until you find your sweet spot. d. Build a core vocabulary base: I used this anki deck, then later focused on reading. Today, I’d have used this deck, instead. Ten new cards per day is plenty. As a rule of thumb, expect that in a month, for every one “new” daily card you’re learning, you’ll also be doing 10 “review” cards. 10 new cards per day means 100 review cards per day. As for how many words you need, please refer to this article’s discussion section (p24). Then, this blog post demonstrates what 80%, 95% and 98% comprehension feels like. 4. Next, build a house on that foundation. Learning becomes more personalized (Stage Two). a. Consume content: Japanese isn’t one thing, it’s a holistic compilation of many interrelated skills. You’re infinitely closer to being competent in any one of those skills than mastering all of them. If you want to read, start reading. Want to watch anime? Do that. Want to have conversations? Have them (II). By spending time engaging with real content, you’ll develop the unique skills you need to better do the things you enjoy. b. Refine your knowledge: Immersion is almost like magic. Sheerly by engaging with the language on a regular basis, you’ll expand your Japanese world and give it color. However, the knowledge you gain will often be a bit fuzzy. Grammar/reading comprehension workbooks will help to iron those kinks out, ultimately enabling you to immerse more efficiently. Progress is a cycle of expansion and refinement (II). 5. Finally, upgrade to a mansion if you need and want the space. If you don’t… don’t. a. An intermediate learner can do most things with preparation; an advanced learner can do most things at the drop of a hat. Do you need souped up Japanese? Probably not. Very few people need to be as proficient as a native speakers, and even native speakers have limitations. Chances are, the amount of Japanese you need in order to do what you want is significantly less than anything resembling “advanced”, let alone “bilingual”. This document is about setting ambitious goals, then later trimming to fit your needs. * The most useful piece of advice I was ever given is that quantity, eventually, becomes quality. With time and trials you’ll gradually figure out things that work for you, fix problems and address weaknesses. With each failure you’ll reinforce the floor of your knowledge, and bit by bit, it’ll become strong enough to stand on. However you get through Step 3, it boils down to “find a source of grammar/vocab/kanji and stick with them 1. Some people like to get kanji out of the way first because they love the characters or are intimidated by them. That’s great! Being confident with kanji makes Japanese easier. Divide and conquer! 2. Some people like to do vocab, grammar and kanji at once, a bit each day. That’s great, too! Generally speaking, knowledge is more easily converted into memory when consumed in frequent , small doses. 3. Some people don’t actually study that much, and that’s great, too. There are a lot of valuable things to spend your life on, and an important part of this is learning how Japanese fits into your big picture. The only “right” answer is the approach you’re able to stick with. Your progress in 5 years will dwarf whatever you can accomplish this year, so make virtues out of consistency and sustainability. Page 5 Introduction The post I originally responded to was by a user in /r/LanguageLearning who explained that they had one year to prepare and wanted to learn as much as possible before going to Japan. Similarly, many people want to know how long it will take to learn Japanese and, based on their unique circumstances, whether or not they can do it within a certain period of time. I want to briefly touch on both of these questions before getting started. How long does it take to learn Japanese? This question is difficult to answer, but a few organizations have tried to do so. There is a discouraging (yet understandable) lack of congruence in the numbers they’ve put forward. ● ● ● ● The JLPT themselves estimated that it will take about 900 hours to pass the N1 The US Government estimates it will take ~2,200 in-class hours (II) (not including homework) A 2010-2015 study of students studying Japanese full time, in Japan, estimates that it will take 3,000-4,800 hours for students without a background in kanji to pass the N1. I failed the N1 by a few points in Jan’21. I hadn’t touched Japanese for over a year at that point, and the JLPT test format sort of threw me off (take a practice test first!), but the fact of the matter is that 5,000+ hours (liberal guess) wasn’t enough time for me to pass the N1. Whatever you might take from these numbers, they leave a few important questions unanswered: ● ● ● ● ● What does an hour of studying entail in the first place? Are all of these hours equal in nature? Are some more “valuable” than others? Do they have to be hours of study? What about hours conversing? Reading? Of anime? How should you block out those hours? One long session? Many small ones? In boxes? How proficient must you be to say that you have “learned” Japanese, anyway? The only answer I can possibly give you is that learning Japanese takes a lot of time, and depending on your particular goals, it might take more or less time. Reaching conversational proficiency takes comparatively little time, for example. If you’ve never thought about how much Japanese you actually need/want, here’s a survey asking people of different proficiencies what they do and don’t feel confident doing. Respondents are people who barely passed a given JLPT level, so this is a decent representation of what each additional JLPT level of proficiency should realistically enable you to do. The most important takeaway is that you don’t have to be bilingual to express yourself. Although it would be cool to be perfectly fluent in Japanese, you can probably achieve your goals with far less. Page 6 Anthony Lauder on measuring time spent studying Anthony Lauder, author of the Fluent Czech blog, suggests that we focus on minutes, not years. His suggestion comes from a quote by the pianist Michel Petrucciani: Every hour I am at the piano feels like a minute. Every minute I am away from the piano feels like an hour. Forming the crux of his video, Anthony ultimately suggests that the secret to learning a language is to absolutely love it: [To study in such a way that] Studying isn’t a chore, merely a task to get out of the way so that you can reach that fluency you lust for—no. Lust fizzles. But if you love the language, if you love the language learning process—those hours, those months, and those years—they’ll fly by, and it’ll feel like minutes. And that’s the way to fluency; to fall in love with the process… and then to do what you love, for hours and hours a day, for years and years, but for it to feel like minutes. This idea of “loving” the language has been an integral part of my personal learning philosophy. I believed that the only thing I could be confident of was that learning Japanese was going to take a lot of time, so I wanted to be sure that I would enjoy myself. As Lydia Machova, a polyglot who interviewed lots of other polyglots, says: We aren’t geniuses… the one thing we all have in common is that we [find] ways to enjoy the language learning process… all of us use different methods, but we make sure it’s something we personally enjoy. If you come out of this post with anything, I hope you come out of it with a furrowed brow, curious about how you can connect Japanese to the things that are important to you. Why learn Japanese? I personally love reading, so I made a job of finding something that I wanted to read in Japanese—something that wasn’t available in English and that I wasn’t yet good enough at Japanese to understand. It turned out to be a collection of short stories by 結城昌治 (Yuuki Shouji), a guy who doesn’t even have an English Wikipedia page. I believe that everybody will learn a language to as proficient a level as they need to—no better, no worse—and that, frankly, most people have no need to learn a language. That in mind, I think that step one for every single learner is discovering (or creating) a reason to learn Japanese that is concrete enough to let you to personally justify the time you’re going to spend on it. Your first job is figuring out why you are going to learn Japanese. Page 7 About this document, about me About Me: Should you listen to me? I’ve gone from zero to (at least) functional in four languages: Spanish, Japanese, Russian and Mandarin. Spanish aside, I’ve also done that over a ~5 year period of time (as of ~ Oct 2019). Looking at so many languages over such a short time frame means that I’m far from perfect in any of them. ● ● ● ● ● I have lived in Russia, Japan and Taiwan; these languages have been parts of my daily life. I love reading. I care much more about literature than conversation/movies. I like writing. I’ve written for FluentU, LingQ, and random stuff on Reddit. I have tutored adults and done test prep; I’ve seen the results of many learning styles. I am not a linguist, professor, interpreter or translator and have zero certifications In short, no. I don’t think that I am qualified to teach you Japanese. I don’t plan on doing so. About This Document: What am I doing here? While I don’t feel comfortable giving you lessons on Japanese grammar or a history of the kanji, that doesn’t bother me too much. There are knowledgeable and passionate people who have already made (many) resources doing so, and I do feel comfortable pointing you towards that content. After four languages, more than anything, I feel comfortable talking about the big picture behind what learning a language entails. I’ve learned formally and informally, with and without immersion, as a broke student and as an adult working 60 hours/week, via English and via my target language. My goal here is to guide you to a point where you can begin focusing on immersion, learning by doing the things you enjoy doing. In my personal opinion, that’s where the intermediate level begins. I’ll talk about what you need to do to get there—or, at least, how I go about doing so. Think of this as being a kind of interactive syllabus, or maybe a map. I’ll tell you generally where you need to go, present many resources and help you plan your route so that you can go more efficiently. Ultimately, though, a map is just a piece of paper. You’ve got to do the learning by yourself. In a nutshell This entire document can be summed up in a few bullet points. It is: ● A reflection on my journey through Japanese, loosely organized into a timeline ● An organized compilation of resources that I used or bookmarked at some point ● A lot of discussion on everything to do with learning Japanese, plus further reading As an aside, I don’t have anything to sell you, either. The feedback I get from y’all is helping me learn to express myself more clearly. Hopefully I can apply those lessons to writing fiction someday. Page 8 How to use this document There are many different types of people, and all of these people conceptualize, approach, deal with and reflect on the problems they encounter in different ways. I’d like to ensure that everyone can make use of this document in the way that best suits them, but I don’t know you, your level in Japanese or your background in linguistics. That makes my job very difficult. My attempt to work around this is to trust that you know yourself, and if presented with the right resources, are capable of choosing what best suits your own style, interests and needs. Consider each chapter to be a landing page: I’ll provide the basic context you need to make intelligent decisions, then present you with nails (challenges) and a few different hammers (tools). So long as you get enough nails in more or less the right place, the shelf you’re building will stick to the wall. The basic structure of each chapter: ❖ Opening Words Motivational words, my general thoughts on the topic and my goals for the chapter ❖ Overview What I absolutely expect you to do is highlighted orange. What I recommend, but can accept that not everyone cares about, is highlighted purple. All of this will be elaborated on. You don’t need to follow the links if you read the chapter. ❖ Expansion An expansion on the above: how to do it, why I’m suggesting that you do it, further reading and some essay-type sections covering the most important insights that I’ve had. My hope is that organizing the document like this will allow different types of learners to derive value from my document. Some people might just want help getting their feet under them, others might just want food for thought about a specific topic, some learners might want to have their hand completely held. I’m game for all of that. Hopefully there can be something here for everyone. I’d like to emphasize that this document is more a series of landing pages than anything. In each chapter I’ll provide some infrastructure and rules of thumb, but I haven’t strung things together enough to be able to call it a step-by-step guide. That’s a goal for the next version of this document. For the time being, if you’d like to see more chronological reflections on peoples’ journeys through Japanese, please refer to the list I’m compiling in the appendix. Note: if you see forward slashes (ie, //1.33b: Popular Kanji Resources), this means that I am currently editing this section. Content before the slashes should be nicely put together, content after it may be somewhat haphazard. You can always send me a private message on Reddit if you’re confused. Page 9 Some closing words I began my original post by stating that one year was an obnoxious timeline, and I will do the same here. I have never taught anybody Japanese. I have no idea if this is feasible, let alone reasonable. Please do not take this as something tried, tested, or foolproof. It’s what did and didn’t work for me. What I can say is that I only spoke English until I was 20, but now at age 25 am comfortable reading, watching dramas, and chatting in Japanese. I don’t have a special knack for languages—I studied Spanish for six years before Japanese, but only reached an ~A2 level—so I’m sure that you can find your way through Japanese, too. A lot of learning a language is learning how you (you) learn. Here’s a zoomed-out timeline of my personal journey through Japanese: Year One: I spent a year at a university in Japan; 4 days of Japanese per week. Year Two: I returned to the US; no Japanese coursework available, so I slowly revised kanji. Year Three: I returned to Japan; didn’t like my classes, focused on reading/immersion. Year Four: I moved to Russia for work; lots of reading, joined JP/RU exchange club. Year Five: I moved to Taiwan for work; read in Japanese, but began focusing on Mandarin. Year 6/7: The occasional book/podcast aside, most of my time goes to Mandarin. I wrote my original post figuring that if you were to study more consistently and without so many breaks, you could probably even accomplish in one year what took me three. Notice that there are three further years after those first three years of study, though. I included them to emphasize this: You will not become fluent in one year. I am not fluent after six. I still have a long way to go. I can do everything I want in Japanese, but that’s not the end game. Working in Japan in Japanese also entails confidently doing lots of stuff I don’t care about doing, and that’s still far from bilingual! What I can say is: You will make significant progress this year. At the least, it’ll be a cool experience. One final time, here are my goals for you this year: - Develop all of the foundational skills you’ll need to take learning into your own hands Make headway into one “stage two” skill that matters to you (reading, listening or speaking) From there, have a plan in mind to develop other skills and eventually become well-rounded That’s all great, but it definitely stops far short of any notion you might have of “fluency”. As you continue learning, I think you’ll find that nobody has all of the answers. My biggest goal is to see you become independent, capable of finding the answers you need in Japanese by yourself. Page 10 Stages of Language Acquisition There are a number of conceptual stages of language acquisition, several theories attempting to explain how we progress through those stages (II) and many tests that attempt to assess which stage we’re currently at. In Japanese, that test is the JLPT. People have devoted their entire lives to researching how we learn languages, and I think that serious learners will benefit from becoming familiar with those major schools of thought. Having said that, as an independent learner, three particular transition points stick out to me. Given that this document is my own reflection, I’ll base it around the four stages those points suggest. ● ● ● ● Stage One: You don’t yet know enough to learn independently and you understand so little Japanese that any sort of activity, be it input (reading/etc) or output (speaking/etc) is unbearable. This stage is defined by active study and memorization. Everything we do will be for the purpose of tipping the scales to allow you to meaningfully engage with Japanese. ○ The ‘Nope’ Threshold: This is the transition between stage one and two. This is the point in time where you subjectively feel that immersion is now tolerable. Not easy, not natural, not even efficient, but tolerable. You can stomach it without ‘noping’ out. Stage Two: You’re now capable of taking the reins and engaging with content that you find meaningful. Doing so will present you with all sorts of problems, and in overcoming them, you’ll develop the unique skills you need to engage with Japanese in the way that is most enjoyable and meaningful to you. This is the most exciting stage of learning anything, IMO. ○ The Epiphany Moment: This is the transition between stage two and three. It has been different in each language for me, but something will prompt you to reflect on your past ability and you’ll realize that Japanese isn’t so difficult for you anymore. Stage Three: You’ve worked out enough kinks that immersion has become a thoroughly enjoyable process. Learning is basically a byproduct of doing the things you enjoy, and you’ve likely got an ever-growing backlog of stuff you want to read/watch/listen to/etc. ○ The Hurt-Ego Moment: This is the transition between stage three and four. After tons of successful immersion, you run into a major wall:. Maybe you performed poorly or just couldn’t get through some book. It spurs you to change things up a bit. Stage Two+: You begin refining an old skill or start at stage two in a new one. There are many hurt-ego moments and many stage-two+’s that ultimately lead towards mastery. My first conversation, first time recording myself, first time getting feedback on my Japanese writing, first time taking a JLPT prep test, first time reading a book not by Murakami Haruki, first time watching Japanese comedy, first times translating and interpreting… tons of stuff. On Moving Through Stages Some learners might feel comfortable moving on at a point where others would still feel uncomfortable. It just comes down to patience (how willing are you to look up things you don’t understand?) and tolerance for ambiguity (how bothered are you by not understanding?). Page 11 Stage One: Building A Foundation There are a lot of different ways that we can use language, and depending on what you want to do with Japanese, you’ll need to develop different skills. All of these skills exist on a spectrum. Stephen King, Angelina Jolie and Dave Chappelle are all native English speakers, all renowned in their respective fields, and all making use of different skills to do what they do. You aren’t simply “good” or “bad” at language, you’re better or worse at specific things in that language. I think that you’ll develop the skills that you personally need to better do what is important to you as a natural byproduct of simply doing those things, whether it’s reading or conversing. My first priority is bringing you to a point where you can begin doing those things, whatever they are. 1. Chapter One and Two: The kana and their sounds This knowledge will be necessary to use practically any Japanese learning resource a. Pronunciation: Learn about the sounds that exist in Japanese i. Phonemes: Some sounds are the same as in English, some aren’t. At the least, become aware of these new sounds so you can listen for them. ii. Prosody: This is about how sound connects: rhythm, intonation patterns, etc. Japanese prosody works quite differently than English prosody does. b. Kana: Learn the two syllabries that Japanese uses to represent those sounds. 2. Chapters 3-5: Build a vocab/grammar base so you can begin immersing a. Kanji: There are 2,136 “daily-use” kanji; some occur more often than others (II). i. Learn how the kanji are constructed and used ii. Learn to recognize (and, optionally, write) most of these daily-use kanji b. Vocab: You need remarkably few words to begin conversing, more to do other things i. We’ll begin working through the ~2,000 words that occur most frequently in Japan’s main newspaper. You’ll also get a feel for how kanji and kana interact. ii. Language isn’t math. I’ll talk about why just learning words won’t cut it. c. Grammar: Grammar is how you describe the relationship between words. i. We’ll work through Genki I, II and the associated workbooks. There’s much more, but you’ll see the grammar in these books come up everywhere. ii. Grammar isn’t something you cover once and then master. I’ll talk about why. The 50% Rule: How you know when to move on My stages are less concrete steps and more a suggestion of what to prioritize and when. Moving onto step two entails significantly decreasing the time you spend actively studying and investing that time into whatever feeds your soul. If you aren’t engaging with Japanese content already, I encourage you to regularly "check in” with something. I’ll give more explicit instructions later. For now, this is a litmus test. For a while, all Japanese content will seem like a brick wall. Or Greek. One day you’ll say wait a minute, I think I could do that— boom, you’ve cleared The Nope Threshold. But to come to that realization, you have to periodically try to do something (anything) in Japanese. Page 12 1.10 Pronunciation How English sounds to non-English Speakers: Step one is learning to recognize Japanese sounds Page 13 1.11 Opening Words I’m going to begin by saying that, while pronunciation is important to me, it might not be to you. That’s okay. Here’s a speech by Jay Rubin. He’s the translator of Murakami Haruki, a professor at Harvard… and his pronunciation isn’t that good. Pronunciation, obviously, isn’t everything. Anyhow: ● ● ● The sh sound in Japanese し (/ɕ/ ) and English she (/ʃ/) are not the same, but people will understand you just fine even if you always pronounce し as /ʃ/. You’ll just sound foreign. Pitch accent is a thing, and it is a big thing—but unlike Mandarin or Vietnamese, people will be able to understand even if you frequently make mistakes. You’ll just sound foreign. This more or less goes for every other point I bring up in the pronunciation section. Having said that, there are a few reasons why I like to start with pronunciation: 1. I think that an important first milestone is just getting your foot in the door, and sound is accessible. Despite being a foreign language, Japanese shares many sounds with English. 2. Over the next 6-8 months you’ll be memorizing about two thousand simple words. Developing an ear for pronunciation now will help you to soak up more while doing that. 3. Our ears often deceive us (II), and foreign accents are often a result of imposing pronunciation knowledge from our first language onto our second. Knowing where Japanese and English pronunciation differs from the get-go lets you avoid headaches later. 4. It’s fascinating, frankly, and it’s everywhere. Learn the basics of phonetics and prosody and you’ll find yourself noticing cool stuff when you listen to anything in any language. Finally, I’ve got a few basic goals in this section. I based the progression on Antimoon’s post why pronunciation is important (II) and The Mimic Method, so consider checking them out, too. Basics is for people who otherwise will skip pronunciation. Please, give me one hour. Prosody/Phonetics introduces key knowledge that will help you to pick stuff up as you go Practice consists of resources and exercises for learners who want to learn by doing When we speak with a foreign accent, what we do is we take patterns that we know from our native languages… and then apply them to English. We don’t do it consciously, that’s just what organically comes to us. But if the patterns of our native tongues are different than those of English, the result is that the… message... isn’t going to be clear. Although you know how to construct the sentence, the words are accurate and you don’t make any grammar mistakes… but if you don’t distinguish the right words, if you don’t stress the right words and put emphasis on the words that are stressed, you become unclear. [Pronunciation is about] recognizing your speech patterns and listening to how native speakers speak, which helps you to understand how [a language] should be spoken. ~ Hadar Shemesh on Melody, Stress and Rhythm in American intonation Page 14 1.12 Overview (This is the chapter condensed into one page. If you read the chapter, you’ll eventually cover all of this.) As I explain in the grammar section, I think that there are several steps involved in learning anything and that they tend to happen over time, rather than all at once. While very few achieve a native-sounding accent, an accent that’s easy to understand is within reach for anyone. The information here is the densest part of the entire document. It will take time to sink in. Basics — to be done alongside the kana section. If you do nothing else, please skim this. 1. Get started with an easy overview of Japanese sounds in relation to English. I, II and III. 2. Do not dipthongize or reduce your vowels. You probably do this without noticing. 3. A few more no- or low-effort steps you can take to sound better: I and II 4. Please read this post on why pronunciation is important Prosody — this stuff is complex; work on it over time. pick one idea at a time, then make a point to listen for it in EN/JP. 1. Figure out what prosody is. You’ll want to know about stress, rhythm and melody; connected speech and phrasing; intonation and pitch. 2. Once you’ve got your head around that, listen for (below) when you consume Japanese: a. Pitch Accent: In 10 minutes, in written form, with visuals, compared with English b. Rhythm: the basic rules and in comparison with English c. Connected Speech: It’s all over English (II). It’s not a thing in Japanese. Don’t do it. You should be saying ka-n-ji, 3 beats. Not kan-ji, 2 beats. Phonetics — also important, but I think you’ll get more bang for your buck with prosody. Do this afterwards. 3. Learn how to read the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). It is a blueprint for making any sound, telling you: Where it’s made, how it’s made, if it’s voiced, and more. [Anki deck EN|JP] 4. Compare and contrast the sounds that exist in Japanese and in English — like this. 5. Vowels are more flexible (complicated) than consonants. Learn how they’re described, learn how to read a vowel quadrilateral, then compare the vowels of Japanese and English. Practice — further reading/practice that I feel is useful enough to warrant giving space to in this TL;DR 1. Understanding something, nailing it in practice and using it spontaneously are different things. Here are reasons teachers fail to teach pronunciation, with solutions. (ie: I and II ). a. Here’s how I approach listening to stuff (see bottom) and practicing new sounds. 2. Record yourself and listen to yourself speak. I wish I began doing this six years ago. 3. Genki updated their dialogues to include pitch accent, and they’re free: Genki I and Genki II. 4. Consider following Dogen’s course on Pitch Accent; otherwise, learn how nouns and verbs/adjectives work, then slowly memorize pitch accent conjugation patterns (don’t do the entire deck; it’s just for getting a big picture of how the patterns work). a. Some anki decks include pitch accent; you can also make your own (I and II) 5. For lecture type content, see Virtual Linguistics University or Fluent Forever’s app (review). 6. I like “shadowing”, but not everyone approves of it. I see it as a discovery process that helps me identify weak areas to practice, so first and foremost, figure out what you’re listening for. 7. The free Speechling app lets you get free feedback on your pronunciation, ~once per day. Page 15 1.13 Pronunciation Homework 1.13a Basics You might not care about developing a natural accent, and I’m not about to try convincing you one way or the other. As a rule, I’m going to do my best to simply provide an overview of what options exist, point you to relevant information about each, then let you make your own decisions. That being said, even if you don’t care about pronunciation at all, I’ll ask you to spend 30 minutes working through the below videos. They provide an overview of which sounds you’ll find easy and difficult as a native English speaker, and I think that awareness is important. 1. Watch Fluent Forever’s video on Japanese writing systems + pitch accent (10m) 2. Watch Fluent Forever’s video on Japanese consonants (12m) 3. Watch Fluent Forever’s video on Japanese vowels (8m) 4. Japanese words are composed of kana (hiragana or katakana). Every single kana gets a single metronome beat of equal length. かんじ is pronounced ka-n-ji, not kan-ji. English tends to chunk sounds together (what are you → wha’cha). Japanese doesn’t chunk. 5. English has a pretty complex vowel system; the letter a can be pronounced in 7? different ways. Japanese vowels don’t do that. あ is あ is あ, no matter where it is in a word. I don’t expect you to memorize all of that right now. It’s dense stuff and will take time to sink in. After you’ve had a bit of time to process all of that information: If you’d like to go just a tiny bit further with pronunciation, slowly work through these posts: ● If that was a bit too complicated, here’s a more simply-worded recap of the above videos ● If you’re a native EN speaker, you’re probably pronouncing vowels incorrectly in Japanese. ● Even if you don’t worry too much about pronunciation, pay a bit of attention to these things. Here’s a video on how pronunciation fits into your Japanese development… to summarize: ● ● ● Unlike when reading, you have to parse words by yourself when listening. If you haven’t had the time to internalize how Japanese sounds work, it’ll be difficult to correctly parse the language, muddying your perception of what was actually said Even if you master Japanese pronunciation, you still might not be able to make sense of what you’re hearing. The video discusses this at ~17m and I elaborated it on a post about assessing why you don’t understand what you’re hearing. Finally, please read these posts: why pronunciation is important and what accent reduction entails Page 16 1.13b Prosody When most beginning learners think of pronunciation, they’re thinking of phonetics, the individual sounds in a language. Having said that, there is another dimension of pronunciation that’s referred to as prosody, concerning stuff that happens “above” the level of individual sounds. An example of a phonetics problem is someone saying d because they can’t say th An example of a prosody problem would be saying comPAny instead of COMpany. First, watch this video to get a quick overview of what prosody is. Next, get familiar with how prosody works in English. Start thinking about what sort of patterns exist in your English speech: Stress, Rhythm & Melody | Connected Speech & Phrasing | Intonation & Pitch (dude) After you’ve gotten a feel for this stuff in English, start listening for it in Japanese. You don’t have to dissect people’s speech, just pay attention from time to time and see what patterns you notice. If you can’t hear [a sound], Hadar says, you won’t be able to make it. Right now, just focus on “hearing” it. If you didn’t in the last section… read this post on what accent reduction entails. It’s much more (and less) than you probably think. Rhythm: The low-hanging fruit of Japanese prosody The below two points can be treated as rules of thumb and applied universally. They’re very low-effort steps you can take to improve your pronunciation in Japanese with zero studying. ● ● Japanese rhythm is consistent: each mora gets an equal beat. To-o-kyo-o, not to-kyo Japanese speech is not connected: each mora is distinct. Ka-n-ji, not kan-ji. Pitch Accent (as opposed to English’s stress accent) Pitch accent isn’t as complex as it sounds. We’ve got the same sort of deal in English, but we use stress instead of pitch. In other words, you’re already familiar with the concept of an “accent.” We’ve just got to figure out how it works in English and then contrast that with what happens in Japanese. ● ● ● Stress has a special meaning in linguistics. Read the first paragraph of this wiki. ○ Here’s a comical video about stress accent vs pitch accent (and a short comment) ○ Here’s a video talking about intonation vs pitch accent English employs a stress accent to help differentiate words. In the word university, the syllable ver is pronounced slightly louder and longer than the others. (Try it.) Japanese has a pitch accent instead of a stress accent. Rather than “attacking” a syllable to accent it, it uses musical pitch. Think piano keys, not drum beats. In ta-be-ru (to eat), the pattern is Low-High-Low. Try this out on a virtual piano: Press any white key, then the white key 2 to its right, then your original white key. It’s specifically this pattern, not HLL or LHH. Page 17 That basic definition in mind, here’s a crash course on how pitch accent works in Japanese 1. Dogen on Japanese Pitch-Accent in 10 minutes 2. This wonderfully visual overview from Kanshudo (I particularly recommend this) 3. This crash course in pitch accent (~55min) from Campanas de Japanese 4. Matt from Refold on “the challenge and intrigue of pitch accent” (~2.5k words) 5. Wikipedia on pitch-accent languages (see “Characteristics of Pitch-Accent Languages”) There are four pitch patterns, and you can see each of these patterns covered in more detail here: - Japaneasy - Mora and Pitch Accent (7m) Overview Yas - Intro to Pitch Accent: Heiban vs Odaka patterns (17m) Yas - Pitch Accent II: Atamadaka and Nakadaka pitch accent (7m) Two categories: Heiban (heiban) and Kifuku (odaka, atamadaka, nakadaka) Unfortunately, it still gets a bit more complicated: - Verbs and adjectives conjugate in Japanese, and you need to figure out how pitch changes with conjugation. Thankfully, you only really need to learn two sets of patterns. A very detailed overview of pitch accent conjugation patterns (thanks k3zi) Pitch exists not only at the word level, but also at the sentence level (II) (in more detail). Sentence ending particles, such as 'よ' and 'ね', are also affected by pitch As in English, intonation changes depending on emotions Practicing Pitch Accent As somebody who primarily studies Japanese because I like reading, this is as far as I’ve personally gone with prosody. I understand how it works and am slowly picking stuff up over time, but frankly speaking, that’s probably not going to be enough. Eventually I’ll have to put time in with Anki. If this is important for you, and you’d like to get it right the first time, here are some resources: - Waseda University has a free MOOC that introduces the basics of pitch accent - Dogen has a Patreon video series (US$10/mo) designed to be an accessible intro to pitch accent for beginners. It’s very thorough (~80? videos); you can work through it in a month. - MIA made an Anki version of the NHK Ojad Pitch Accent Dictionary. While I wouldn’t complete it, you can use it to (a) learn each of the 4 pitch-accent patterns in isolation and (b) visually compare the pitch accent pattern of most verb/adjective conjugations. Your goal here should be discovery, not memorization; find patterns you can look for elsewhere. - Migaku made a pair of addons (I + II) that color-code words in Anki to show pitch accent. In my personal opinion, it’s easier to associate a word with bluessness than heiban-pattern. - Some decks (N5 / N4 vocab) include this functionality out of the box. - Here’s a pitch accent resources dump from the WaniKani forums. There’s a lot of useful stuff. Beginners might be most interested in this pitch accent companion for Genki I + II. Page 18 - The Mimic Method has a few free courses on rhythm and intonation Kotu.io includes a minimal pair test you can use to check whether or not you are correctly hearing pitch accent. Accessing the test requires a free account, but doesn’t require an email. 1.13c Phonetics In this stage we’re going to explore and compare how sound works in English and Japanese. There’s a lot of technical information to work through, so I’m going to break it into several smaller bits. Here’s my last request that you read this post on what accent reduction entails. It’s wonderful. Language, and how we represent language At an objective level language is absolutely nothing beyond a set of conventions for communicating through sounds, and we also have means of representing those sounds on paper (aka, orthography). Unfortunately, it’s not quite so straightforward. Language learners quickly run into a few problems: ● Our paper-conventions don't always line up with our spoken-conventions. English has 44 phonemes despite having only 26 letters, and the letter “a” is associated with seven sounds. ● Different languages don’t always follow the same conventions. Compare the sound of pinyin c (as in cǎoméi, strawberry) to its English counterparts in cat or dance. ● Just in case you were starting to wonder: why is English spelling so weird? The International Phonetic Alphabet Out of a need for consistency, Linguists created something called the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). The IPA is a standardized and universal alphabet: /a/ refers to one thing and one thing only, whether it’s in English or French or Klingon. That means that there’s no more funny business like gh representing one sound in through, another in tough, and still another in taught. While it’s called an alphabet, I think it’s easier to think of the IPA as being a set of blueprints. Every single letter in the IPA has a three part name, and each one of those parts gives you important information about how the sound is made. Here’s a crash course in how it works. Consonants and the IPA Let’s get started by learning about what those three parts are for consonants: 1. Place of Articulation (II): the only real difference between P and K is that P is made purely with your lips, K is made with your tongue/soft palate 2. Manner of Articulation (II): the only real difference between P and F is how much air is blocked. With P air stops and “explodes” out, with F air is restricted but still flows out continuously 3. Voicing (II): The only real difference between P and B is that B involves your vocal chords Page 19 So, let’s take that “P” sound that I kept bringing up. It’s called a voiceless bilabial stop, meaning that it’s a sound made using both your lips (bilablial) in which you let air build up and then explode out (plosive), all without letting your vocal cords vibrate (voiceless). If you know the IPA, you get all this sort of information about every single sound, rather than just “it’s kind of similar to [English word]”. Also: Where the air we use to make sounds comes from and how we manipulate that air (II) Vowels and the IPA Vowels are also described in three parts, but not the same ones. While consonants involve certain parts of your mouth touching, vowels don’t involve any touching. This allows for a greater “margin of error” to make a given vowel. The English and Japanese /a/ are made in slightly different places. 1. Basic Segments of Speech: Vowels I (II): 30 minutes, but the best overview I’ve found so far. 2. Height, Backness and Roundedness (II): Very slowly say a few random vowels; you should notice that your lips are making different shapes, your tongue is moving around and your nose sometimes gets involved. Also, a ~10 minute expansion on these concepts. 3. How to Read a Vowel Quadrilateral (in more detail): While consonant charts are pretty straightforward, vowel charts are more visual. Here’s how to make sense of them. Now we’ve covered almost everything you need to know about consonants and vowels. Take a break, and then come back in a few days to read through Tofugu’s post on Japanese pronunciation. It covers the same information as the above two sections in layman-friendly language. Using the IPA to learn unknown sounds Now that you’ve gained the ability to look at sound more objectively, we can put this knowledge to use to both discover what are going to be trouble sounds and also how to correctly make them. 1. Contrast the full list of sounds that exist in both English and Japanese. a. I suggest printing out a chart of English consonants and then using a different color to fill in the Japanese consonants, making the differences easier to see. b. I’d do the same for the chart of English vowels and Japanese vowels. 2. Use your knowledge of IPA to figure out unknown sounds. a. For example, Japanese has this sound: /ɸ/, a voiceless bilabial fricative. English doesn’t have that sound, but that doesn’t mean it’s foreign. Our /f/ is a voiceless labiodental fricative. We thus know that these two sounds are identical, only differing in place of articulation. We’ve also got /p/, a voiceless bilabial plosive. All of /ɸ/’s “parts” are familiar to you, you’re just not used to putting them in this order. 3. Reference Glossika Phonetics’ YouTube channel for breakdowns of each sound. You’ll need to understand IPA terminology to make sense of these videos, but they’re helpful. 4. If you wish, use free tools like audacity to more accurately compare your pronunciation to that of a native. The closer your frequencies are, the better. Idahosa’s Input (also see his interview later on in the document) Page 20 Our end goal is being able to mimic the mouth movements of a Japanese person, and the IPA is a means to that end. It tells you how to move and use your mouth. As you’re learning about this stuff, make sure you’re connecting it to what’s physically going on inside your mouth. Note: This could be covered in much more detail. I’m still learning myself. Might extend later. For example, EN/JP vowels use different tongue positions and different acoustic resonance. General rules of thumb provided by this IPA comparison In short, the soundscape of English and Japanese differs in a few specific ways. 1. English has some sounds that Japanese doesn’t. Don’t make these sounds. a. like the r in green, /ɹ̠ /, or the l in gleen, /ɫ/ 2. Japanese has some sounds that English doesn’t. Learn these sounds. a. /h/ becomes /ç/ when preceding /i/ or /j/, and /ɸ/ before /u/ 3. Some sounds will be affected by interference from English. Clarify these sounds. a. The sh sound in she, /ʃ/ , is not the same sh sound used in Japanese し, /ɕ/ 4. Some sounds are so similar that they’re considered to be the “same” sound, even from an IPA perspective, but they’re actually “ornamented” slightly differently. a. Diacritic markers provide even more nuanced information about sounds. b. English T/D sounds are apical, meaning they’re made with the tip of your tongue. Japanese T/D sounds are laminal, meaning they’re made with the blade of your tongue instead. See the Japanese phonology wiki for more info. c. This chart provides a visual representation of the parts of your mouth. Then, here’s an interactive IPA chart and other goodies from the IPA association. This knowledge helps you to be certain that you’re associating the right sounds with the kana. Other stuff you might be interested in 1. So far as I know, Fluent Forever is currently the only language-learning app available that puts an emphasis on IPA. It was originally a series of pronunciation trainers that got turned into an app. A more thorough review of what I think about the app is available here. 2. Speechling is a flashcard app for pronunciation training: record yourself reading a flashcard, it’s sent to a (real) coach and they’ll give you simple feedback. If you sound clear, you’ll get a thumbs up. If not, they’ll state which part sounds off and send a recording back to you. The feedback isn’t detailed, but it can be nice to get clarification that people do understand you. 3. We referred to Artifexian’s videos for an introduction to the IPA; he has more content. If you’d like to look at these concepts in more detail, here’s a playlist of virtual lectures. 4. Here is a playlist of videos that goes into much further detail about English (can be useful to get a grounding in English) and another on phonetics, phonology and transcription 5. Microlectures, covering a variety of topics in under two minutes: phonetics | phonology 6. Here’s a 3 minute crash-course in how we manipulate our breath to create different sounds. Page 21 7. I’m interested in a topic called vocal resonance. Basically, there are a number of places where vibration occurs when we speak or sing. The unique distribution of where vibration is occuring gives your voice a recognizable “color”. With practice, you can learn to recognize where resonance is occurring and how to direct it. I don’t know enough about it to feel comfortable saying anything yet, but I do think it’s worth exploring. Maybe more later. 1.14 Closing thoughts A lot of people think that studying pronunciation is for the purpose of sounding like a native, but you don’t have either a good accent or a bad one. It’s a spectrum. - Unintelligible: Your pronunciation mistakes prevent you from being understood - Tedious: You’re intelligible, but deciphering your speech is a high-effort chore - Understandable: You’re intelligible, but the listener has to pay attention to understand - Easily-understandable: While obviously foreign, your pronunciation is quite clear - Pleasant: You make small mistakes that give you a “cool” accent, which people like - Native: You would be mistaken for a native speaker over the telephone Unlike Mandarin or French, most people will have an understandable accent in Japanese off the bat. I think that achieving an easily-understandable accent is within reach for anyone, but that not many will want to put in the work necessary to develop a native accent. At least, I don’t, personally. I recognize that this was a pretty dense section, but if you consider the fact that you’re about to commit to learning ● 92 kana (46 hiragana/katakana) ● Over 2,000 kanji ● Several thousand words I think it’s worth taking a small pit stop to get your head around ● The 30 odd sounds/phonemes that exist in Japanese, many of which are shared with English ● The 3 ways that individual sounds are conceptualized ● The 4 main aspects of prosody (aka suprasegmental elements) I heard a recording of myself speaking for the first time recently; it was interesting, and sort of discouraging. I will do it regularly from now on. I recommend you try it, too. Recording will give you feedback on what you’re actually doing vs what you think you’re doing. Pronunciation is physical, so really get to know your mouth! Knowing how to do =/= being able to do =/= consistently doing. As Matt from Refold says: [The root of a good accent] is being able to actually hear what [a given sound] is supposed to sound like—and once you have that down, learning how to actually produce [that sound] and get your tongue moving in the right way is not so difficult. Whenever you’re listening to your target language, you’re hearing it through the filter of your native language. All the sounds are going to [seem] a little closer to your native language, and this is why Page 22 people end up with strong foreign accents... You’ll never be able to surpass your own level of perception; you’re never going to be able to pronounce things more accurately than you’re able to hear… if you’re concerned with improving your pronunciation, what you really have to do is hone your listening skills, and get better at hearing the different sounds in a language. Page 23 1.20 Kana & Memory A Mnemonic and its Journey, from Dr. Moku The Hiragana and their Origins Page 24 1.21 Opening Words (If you’re just finishing the pronunciation, you’re a trooper. The other sections are much less dense. Don’t worry.) Now that we’ve learned about the sounds that exist in Japanese and how they’re made, we can take the next step of learning how they’re represented. Then we can start mixing them to make words. To be clear, Japanese juggles three writing systems plus the roman alphabet, oftentimes within a single sentence. We’ll cover the kana here—the hiragana and katakana—while the kanji will get an entire section to itself. Managing so many writing systems might seem daunting, but as each one has relatively clear use-cases that are very rule-of-thumb-able, you’ll probably be pleasantly surprised by how quickly the mud clears and you get a feel for when to use each one. That in mind, our major goal for this section is actually to learn about two key aspects of memory: 1. Recognition: The ability to see あ, recognize it, and know how what it sounds like 2. Recall: The ability to think of the sound [ä] and pull あ out of the hat of your memory 1.22 Overview During this section we’ll cover the 46 hiragana and 46 katakana. These are sort of like our alphabet (technically they’re called a syllabary) in that they’re direct representations of specific sounds. There are 46 symbols in each system, so you’ll be learning 92 symbols in total. While that might seem like a lot compared to English’s 26 letters, the silver lining is that Japanese is a phonetic language: everything™ is spelled exactly like it sounds. No funny business like use being pronounced one way as a verb (juːz) and one way as a noun (juːs), or the general chaos of English pronunciation. We’ll also take a quick overview of how our memory works, as any program or app you might use is based around the same few principles. Plus, it will make forgetting stuff much less stressful. Recognition - Make a free account over at Read the Kanji and work through the hiragana and katakana - Don’t learn them like the back of your hand; treat this as a crash course. The kana are everywhere, so you’ll get further practice by doing literally anything with Japanese. Recall - Experiment: Download the app Drops, complete the kana course in 5 minutes/day - Recalling information takes more mental effort than recognizing information. It takes less time to learn that で=de than to learn that de=で. This distinction is critical to learning anything, and if you can get a feel for how it works now, you’ll reap the benefits forever. Page 25 1.23 Kana Homework 1.23a Recognition While I typically won’t tell you that you must do something, the kana are one of the few exceptions to that rule. The reason is simple: they pop up everywhere. Whether you plan on following my advice or end up using a different resource, you can’t get very far into Japanese without kana. Look a word up in the dictionary? Kana! Open your textbook? Kana! Glance at the subtitles? Kana! The good news is that, precisely because they show up everywhere, you don’t need to put a lot of effort into this. For now, just get loosely familiar with the kana and then move on with your studies. So long as you build a “container” right now, so to speak, you’ll fill it up with knowledge as you go. So, anyhow, this section is pretty straightforward: 1. Make a free account over at Read the Kanji 2. Work through the hiragana 3. Work through the katakana Read the Kanji’s system gradually introduces you to new kana as you master old ones and also keeps track of how often you get each one right or wrong, showing you less of what you’ve got down and more of what you don’t. It’s very efficient, and you could probably work through all of the kana in a few hours. Try it at some point: sit down and see how many you can work through in an hour. - If you prefer reading, check out Tofugu’s Hiragana Guide. If you prefer watching, check out JapaneseAmmo’s hands-on walkthrough. If you haven’t laughed or cringed today, check out this music video. If you’re not taking this too seriously and just want a break, here’s sambon juku. Here are some cool charts, if you’re a more visual person, by: Coto Academy | u/Danilinky | u/heimsins_konungr | Tofugu Hiragana / Katakana If you’ve got spare mental bandwidth available, I’d also like you to pay attention to how Read The Kanji grades you to determine which kana you should review and when. The major difference between this website and the popular flashcard program Anki (to be discussed later) is a concept called spaced repetition: Anki keeps track of your right/wrong answers to ensure you spend more time on what you don’t yet know than what you’ve already got down, and scheduling periodic reviews (even years into the future) to make sure that information stays down. Anki does this automatically, greatly simplifying the process of committing information to memory. Page 26 1.23b Recall If you’re here, you may have already made an unsettling discovery: the fact that you can see が and get ga does not necessarily mean that you can think ga and recall the hiragana が from memory. First, you’re not dumb, and this doesn’t mean you’ve done anything wrong. In fact, it’s an unavoidable aspect of memory. Understanding something upon sight requires significantly less effort than producing the same information on your own. For this reason, you will passively understand more Japanese than you can actively produce. Below is an experiment you can try. Hours, Days, Cramming and Efficiency In this experiment, we’re going to demonstrate the power of the serial-position effect: 1. 2. 3. 4. Download the app Drops (free on iOS/Android) Select “Japanese” from the list of languages offered Start plugging away at their introductory units on the hiragana and katakana. Generally speaking, pay attention to how you feel. Is it a smooth process? Complicated? etc You’ll notice that free accounts are limited to five minutes of use per day, and this is the experiment. While it will take you more days to learn the kana this way, chances are it will also end up taking you less overall hours than if you were to sit down and repeatedly write out each kana by hand until it was seared into your memory. I personally use a pair of terms to differentiate these notions of time: - Horizontal Time: How many sittings you spend to learn something Vertical Time: How many hours you spend in a single sitting Some things are easier to learn “passively” over a longer period of horizontal time, and some things are better to sit down and hammer out over an intensive session or two. A big part of learning efficiently is figuring out when you should take one approach over the other. For me, this comes down to two factors: - - Complexity: Korean has two systems of numbers. That meant a lot of small and similar-looking parts, and I was constantly confusing/forgetting them. Taking an evening to sit down and put all the ducks in a row saved me a lot of mental bandwidth. Relevance: If memorizing something will let me do something concrete that I can’t currently do, then I’m happy to cram it. For example, when I moved to Taiwan, I learned numbers/food words so I could more easily navigate the night markets. Learning that stuff on day one let me get immediate practice/value that I’d otherwise have missed out on. See Appendix - On Learning—particularly item #3, H. Ebbinghaus—and how memory works (II) Page 27 1.30 Kanji Way back when, only Chinese characters existed: Man’yōgana Many characters could be used to represent any given Japanese sound. This was a pain for all involved, so the kana were derived from specific characters. Page 28 1.31 Opening Words Kanji are a very big hurdle to overcome for Japanese learners, and due to the herculean nature of the task, several approaches to learning them have come about. Many people end up trying more than one in their attempt to get through the odyssey of squiggles. Eventually learners settle on method X, and because they’ve also tried method Y and Z, they can offer convincing examples about why and how X is superior. The issue is that other people have also come to the same conclusion in favor of method Y and/or method Z. These conflicting opinions can complicate things for beginners who are trying to figure out their own route for the characters. What I hope you take from this is that you can succeed with method X, Y and Z. They all work fine. To that end, I’ve got a few specific goals in this section: 1. Explain how kanji “work” — their construction, purpose and general usage 2. Cover a few of the most popular kanji-learning resources and “who” they’re for 3. Provide a bit of optional infrastructure to help you avoid burnout I’m also going to try and convince you that kanji are something you’ll continue engaging with and learning about for a long time, even if you manage to zoom through them in three months. This basically comes down to the fact that you’re going to forget stuff, that forgetting is an essential part of remembering, and a fancy concept called the Zones of Proximal Development. You don’t have to read this last section on memory, but if you’re feeling a bit overwhelmed about how huge of a task the kanji seem to be, I think it will help to give you a bit of confidence. Page 29 1.32 Overview For three types of learners: ● If you already have an idea of what you want to do, feel free to jump to that section. I’ll give you some practical advice and a push into the marathon. ● If you have no idea what the kanji are, are curious about how they work or just generally want to see the tools available to you, skim the purple-highlighted sections before going to the orange one. ● If you’re feeling disheartened or anxious, please see this section’s appendix. I’ll talk a bit more about how our memory works and how you can use that to your advantage, plus my own journey through the kanji and what ultimately did/didn’t work for me over a few years of experimentation. Anyway: How Kanji Work—figuring out why the squiggles are arranged that way - How kanji are constructed, sound and are written - The basic principles that underscore practically all approaches to learning kanji Popular Kanji Resources—systematic approaches to making sense of the squiggles - Determine whether you’d like a structured or hands-off approach to learning the kanji - Pick one of several (not necessarily recommended) resources to work through Avoiding Burnout—making the most out of whatever resource you choose - Abecedarius - Abecedarius Appendix—my personal kanji journey, plus some hot-button issues worth thinking about - Sudoku and the Incremental Nature of Learning (zones of proximal development) - Abecedarius - Abecedarius Page 30 1.33 Kanji Homework 1.33a: Making Sense of the Squiggles Please work through the following links: - How Kanji are Built: The six different types of kanji you’ll encounter (II). - How Kanji Sound: The On’yomi vs The Kun’yomi and Phonetic Components in Kanji - How Kanji are Written: The Basic Rules of Stroke Order (p7) Pretty much any resource you might use to learn the kanji is based on the below principles, so it’s in your best interests to be familiar with what’s going on in your memory. Please work through the links below, too. You don’t have to work through all of them in one sitting; just, generally, explore. 1. Break the characters down into more tangible chunks. Read the introduction to RTK (~11 pgs) Source: kanjidamage 2. See Link Go! - Take the arbitrary chunks and string them together with a vivid story Source: Nelson Dellis, 4x memory champion. Really, watch the SLG! Video. 3. Employ spaced repetition (what it is/how to apply it) to ensure you remember the kanji. If you’re interested in learning more about memory, here are two deeper dives: spaced repetition (26min) and active recall (20min). Page 31 1.33b: Three Routes Through the Kanji I’m going to offer three approaches to learning the kanji: one gives you complete freedom, one holds your hand, and the other is a compromise. People have succeeded with all of them, so choose the one that makes the most sense for you. Two things I’d like you to keep in mind: 1. There are a lot of kanji, but they are not equally useful. Consider these two analyses of the frequency with which kanji appear in a selection of books (one + two). There are some 3,000 kanji in RTK, but there are less than 1,800 unique kanji in Harry Potter #1 and ~1,750 in Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood (plus some for names). Looking at the data for HP#1, of those 1,800 unique kanji, less than 80 appear over 100 times. Over 800 characters appear less than 10 times, and ~250 appear only once in the entire book. Simply put, some characters offer more bang for your learning-buck than others. On the other hand, 歴 is very common, while 麻 isn't. But if you know 麻, it’s easier to remember 歴. So do you skip 麻, since you you’ll very rarely use it—or do you learn it, since it's a component of a very common character? What I want to say: If you straight-up memorize all 3,000 kanji in RTK, you’ll learn a bunch of kanji you might never see again. If you don’t go through RTK, you’ll find yourself encountering new characters for a long time. Pick your poison. 2. I first did RTK six years ago, and I no longer remember most of the stories I painstakingly constructed and memorized. When I see 相談, I don’t see “inter” and “discussion,” I just see soudan. It’s totally automatic, in the same way that when I see discussion, I don’t see the individual letters nor do I see dis- (latin for “apart”) or quatere (latin for “shake”). Sometimes I don’t even “read” the kanji, I just run my eyes over the page and the meaning wells up on its own. So, are all those stories useless because I’ve forgotten them? Or did my kanji knowledge only become so automatic because the stories gave me a handhold to pull myself up with? I don’t know, so I can’t tell you what to do. Decide for yourself, then refine your process as you go along. Most importantly, whatever you choose, you’ll be investing at least a few hundred hours into this. Most likely more. That in mind, please set aside a couple hours to skim through the different approaches available and consider the pluses and minuses of each before making your decision. There seem to be three general approaches people take to learning the kanji: - Hands Off: Learn the bare minimum necessary to jump into Japanese content Hands On: Learn an overkill amount of information about the kanji now and coast later Middle Path: An attempt to minimize the negatives of the above approaches Page 32 The Hands-Off Approach: Sink or swim You get the infrastructure necessary to learn the kanji, and that’s it. Learn the remaining kanji as they come up while immersing. This approach has minimal overhead and ensures you dont waste time learning anything not relevant to your unique needs, but your jeans will need many patches. 1. Go through all of the links in 1.33a. You’re building your own lifeboat with this approach. 2. Learn about the radicals (bushu), the small lego blocks that all kanji are made of. Pick one: a. Here’s a deck of all the official radicals, as Japanese people know them b. Here’s a deck with a mix of radicals and radical-like components (DIY) 3. Here is an anki deck containing the ~450 most common kanji, many of which double as radical-like components that are combined to create more complex kanji Once you finish memorizing the ~700 anki cards in these two decks, you’re on your own. Make your own Anki cards in order to learn the unknown kanji you come across while immersing. You’ll end up with a very lean deck that has been customized to suit your specific learning needs and interests. A few tools you might find useful: 1. The Kanji Koohii Website (backup) is an index of all the kanji in RTK, each with community-sourced mnemonics and a list of vocabulary that each kanji appears in. 2. The Kanji Grid addon for Anki crawls your Anki cards in order to generate a heatmap of all the kanji you have encountered, how well you know them, and which you still need to learn. // I would look into Migaku’s kanji addon for Anki The Middle Path: Swim, but bring a life vest This is a more fleshed out version of the hands-off approach… or a leaner version of the hands-on approach. You’ll learn the 1,000 most frequently used kanji, which is enough to cover 90% of written Japanese. This deck includes 250 additional cards for radicals, so it’s an all-in-one resource. The Hands-On Approach: Nevermind swimming, give me a boat You start an already-established system that will take you through two- to three-thousand kanji, simply opening your application of choice each day and learning whatever it tells you to learn. This approach requires the least planning from you, but is not tailored to your needs/interests at all. Here are a few different courses through the kanji; pick one. Page 33 1. All in One RTK/KKLC + Vocabulary Anki deck My personal choice - it provides kanji in a variety of fonts, shows how they break down into their constituent radicals, provides sample vocabulary words for each kanji, and more. First learn to recognize the kanji, later enable the “production” mode if you want to learn to write them from memory. I like this deck because it offers as much or little detail as you wish. This deck is a combination of Remembering the Kanji (sample available here) and the Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course (don’t think it’s available in book-format anymore?) a. RTK treats kanji as being lego-like constructions: mix different legos in different ways to get different kanji. In each chapter he gives you new “blocks” and shows you what kanji you can build with those blocks. Many systems employ the same strategy. What’s controversial is that Heisig feels that learning the kanji is such a monumental task that it requires your full attention: he suggests learning what ~3,000 kanji mean, and how to write them, before you begin doing anything in Japanese. Before even learning how to pronounce them. No vocabulary or anything, just kanji and an associated English keyword. Many people agree; many people disagree. b. The Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course is popular among people who don’t like RTK/Heisig. A couple core differences between the KKLC and RTK is that the KKLC system rejects Heisig’s claim that it isn’t helpful to learn readings/vocab alongside kanji and that it’s important for learners to make their own mnemonics. All of this information is provided for you as you learn each kanji. Each kanji in the KKLC is introduced like this: sample page KKLC 2. WaniKani WaniKani is a paid resource that heavily curates your path through the kanji. You have to follow their program, but they’ve organized everything for you, so all you have to do is log in every day and do what they tell you. You’ll learn ~2,000 kanji and ~6,000 vocab using those kanji in a year if you learn optimally; most people need closer to two years. Here’s a useful (IMO) reflection by someone who finished WaniKani: 368 Days of WK 3. // Not sure where to put this yet, but if you like the idea of RTK (breaking down kanji into smaller chunks) but don’t like the idea of learning 3,000 kanji before you do anything else with Japanese, you’d probably be interested in this sort of approach from Brit Vs Japan. 4. Other options (alphabetical order): Page 34 a. Kanji Damage is another take on RTK. He ignores a lot of kanji that he feels aren’t worth the time to learn (ie, characters like 桐 for “paulownia”, a type of tree). He aims to introduce only the kanji you’re practically going to need. Often crude/NSFW. His website includes several explanatory pages, so go check out what he has to say. b. NihongoShark has been in the community for ages and this is his take on the most optimized way to learn kanji. It’s a condensed version of RTK (2,200 vs 3,000 kanji), trimmed down to include only what you need to know for the JLPT. He talks about what he recommends you to do and why he organized the deck like this in his post on learning the kanji—if you like his style, he offers a whole guided system. c. Read the Kanji, the resource we used earlier to learn the kana, is actually a kanji resource. It breaks the kanji up by JLPT level and allows you to cram; unlike the kana, each kanji comes with an example sentence. There is/was a pretty active community that comments on each sentence/kanji, too. This system doesn’t break down the kanji for you, though. If you’ve been following this guide then you should already have an opinion about Read the Kanji. If you like it and don’t mind breaking the kanji down yourself, feel free. Closing Thoughts Whatever approach you choose, remember that all of these approaches are merely training wheels. You’re not ready for the Tour de France just because you took off your training wheels. At this point you can more or less stay upright on your bike, so now you’re looking at an indeterminate amount of seat-time ahead of you. The more you read, and the more vocabulary you learn, the easier Kanji will become. Eventually reading the kanji will become as natural as reading the alphabet. More than that, you’ll become able to make educated guesses about how unknown words are pronounced and even what they might mean. Your first foray into written Japanese content will likely be miserable, but it will also be exciting, and it will get easier as you go. At the end of the day, this isn't rocket science. Seven astronauts aren't going to die because you made a calculation error. You just have to stumble your way through enough of the basics to get into real Japanese content (which probably is less Japanese than you expect, and why I recommend people to apply Drawabox's 50% rule). Once you're spending regular time in Japanese, many (not all) of these holes will fill themselves. Pick something, be consistent, and get to that point. Page 35 At the end of the day, even if one way or the other is more efficient, it isn’t that big of a deal. We live for a long time, and most people don’t have a reason to speed-run Japanese. Maybe you need to play with the kanji for six months or a year or three. All you really have to do is hang in there until enough pennies are stacked up that you come out with a dollar and get your foot in the door with a book or TV show or manga that kicks off your Japanese-content-consumption journey. //1.33c: Some Infrastructure to Avoid Burnout If you’ve chosen to use another deck, you should be following their system for the rest of this section. I encourage you to do so. If not, this is how I would re-approach the deck that I used. Learning to recognize // will heavily work this in v2, I know it’s a mess, sorry. 1. First, take 10 minutes to review what kanji are and how their stroke order works. 2. Figure out how Anki works (less detail/more detail). I use these addons/modifiers, too. 3. Go download this deck that follows Heisig’s RTK. 4. In Anki, go to browser > search by card type > “card:Recall” > suspend all of the recall cards. This isn’t about being thorough, it’s about achieving a minimum marketable product. I do this to get into content asap, and then spread out the process of learning to write the kanji. 5. Set “new” to 5 per day. Do 5 cards every day and you’ll finish in about 2 years (see below). 6. Download the associated radicals deck (what radicals are for [text]). For now, suspend all of the cards in the deck. Unsuspend them as they come up in the kanji you’re learning. (This step is optional, especially if you’re using the physical RTK book) 7. The deck I’ve suggested includes a lot of information about each kanji, including vocab words that include it. If there aren’t any vocab words, or none of them seem useful to you, search the kanji in a dictionary and pick a few vocab words that you think are better. ( You don’t have to try to memorize any of that stuff; just have them there so that you see them when you do your reviews. I think that step one is just knowing what exists. ) 8. *** I think most people will be comfortable doing more than 5 kanji per day. I don’t expect you to stick with 5, I’d just like you to gradually up the amount you do each day in order to find your sweet spot, wherever that is for you. This will help you to avoid burnout and doesn’t cost you very much time. If you start at 5 per day and up it by 3 daily cards at two week intervals, gradually working up to 20 cards per day, you only lose a month compared to if you had started from 20 daily cards right away. I think that’s a reasonable tradeoff. Week · Pace W2 W4 W6 W8 W10 Day 150 D182 @20/day 280 560 840 1,120 1400 3,000 --- @5/day 70 --- --- --- --- --- --- @8/day --- 182 --- --- --- --- --- Page 36 @11/day --- --- 336 --- --- --- --- @14/day --- --- --- 532 --- --- --- @17/day --- --- --- --- 770 --- --- @20/day --- --- --- --- --- 2370 3,000 Learning to write (how I approach this) 9. I take a bit of an unconventional approach to learning to write kanji and I discuss this in the section Kanji: Discussion. I made a comment discussing how I do so, and we’ll begin that at around the six month mark. Again, feel free to take a different approach. 10. We’ll begin making the monolingual transition at around the 9 month mark. If you choose to keep following my advice, at that point you’ll start writing down words and their Japanese definition down as you stumble across stuff while reading. This enables you to gradually commit characters to memory while working through stuff that’s important to you; nothing arbitrary or mind-numbing. Page 37 1.34 Appendix Kanji: What I actually did Unless we’re talking about stubbornness and inefficiency, I don’t think I’m particularly special. In this section I’ll walk you through my relationship with kanji. Hopefully it’ll give you some ideas about what to expect, help you discard a few bad ideas and, ultimately, save you some time. Here are the TL;DR points: ● You can get through all of RTK in a few months if you really want to. I did. ● It took only six months of no-Japanese for me to forget most of RTK, afterwards. ● You’re better off sticking to and finishing one resource than bouncing around. ● Learning all 3,007 kanji from RTK is not necessary. Getting through the JLPT kanji is enough to get started reading; realistically, you don’t even need all of the JLPT kanji (cough 麿/朕) ● Flashcards are excellent in the beginning but come with diminishing returns. Know where your line is and don’t feel bad about moving on from Anki once you reach it. ● You don’t need to know nearly as many kanji as you might think to begin reading ● Reading comes with many wonderful benefits—kanji practice included. ● I’m now reading my second book in Mandarin but haven’t intentionally studied any hanzi. I knew enough kanji that I have been able to learn the hanzi I didn’t know via exposure. There is a point where you can begin focusing on organic learning, moving mostly away from Anki, reserving it only for the things you think are particularly important. August 2014: Clueless I first arrived to Japan in August 2014 and was immediately put off by kanji—umm, maybe I’ll just learn to speak Japanese? Isn’t 46 hiragana and katakana enough? More than anything, they just seemed incredibly redundant to me. Writing out the word for to go in hiragana takes three strokes: いく. Writing it out in kanji takes seven: 行く. Why double the necessary amount of strokes? I did my best to ignore kanji at first: I learned the ones I needed for class and nothing else. To prepare for kanji tests I’d open the back of my genki book and write out each kanji with its readings (no vocab included) fifteen times. Needless to say, I very quickly learned to hate kanji. December 2014: Introduced to RTK Page 38 One day I was sitting in the library, preparing for my final test, when a much more advanced friend (six? seven? Semesters ahead of me) walked by to ask how it was going. I took the opportunity to voice my Kanji woes; his jaw went slack and his heart dropped so far that I heard it bounce off the floor. Dude, he said. Please tell me you’re joking. Are you really doing that? I wasn’t joking. My friend introduced me to RTK and suggested that I do 10 kanji per day. He spent the next week walking me through the method, insisted that I had to follow Heisig’s instructions to the letter and let me borrow his Amazon JP account to purchase the book. I wasn’t completely sold but decided that anything would be better than what I had been doing; I’d begin after finals. January 2015: Cue hundreds of hours of RTK I’m slightly embarrassed to say that RTK was one of the most thrilling rides I’ve ever taken. I had originally intended to stick to 10 per day, as my friend had suggested, but ended up doing 15 in my first session (finishing chapter one). Within a week I was doing 50 per day, within two I was spending nearly five hours on kanji per day (winter vacation). Not speaking much Japanese, my newfound recognition of kanji meant independence. I could make sense of signs around me, generally understand what I was eating, follow news headlines in Japanese as they came up on TV. I had followed Heisig’s instructions nearly to the letter: 3,000 hand-made flashcards (see page 43/45). I even gathered 9 shoeboxes and made a physical spaced repetition system to determine what cards I should be reviewing and when. I reviewed only keyword to kanji, and although Heisig said not to, I liked kanji so much that I wrote each kanji from memory with every review. I handwrote ~1,000 kanji (not necessarily unique ones) each day for three months. April 2015: Conquered RTK (or so I thought) If I felt free before, I felt like Superman now. I recognized practically every kanji I saw, and if I happened to see a new one, I could memorize it in less than a second. One day I went to the hospital with a friend who nearly broke her ankle dancing; I understood what was written on the intake forms at the hospital, she didn’t. She was a full time student at our university and was doing her coursework fully in Japanese; I was thinking about taking the N5. RTK was wild, man. This all got to my head (if you can’t tell) and I actually dropped out of my Japanese class. I worked through Genki II by myself, continued practicing kanji, then went home in July. July-Dec 2015: No Japanese I returned to my home university and we had no Japanese courses. I intended to study by myself but with a full-time job, 21 credit hours of class and ~60 page thesis to write, didn’t get around to it. I had zero contact with Japanese in any form during this time. Jan 2016: Started WaniKani Page 39 The study abroad advisor sent me an email saying that a few Japanese students would come to study at our university and it’d be great if I could help out. Part of that included writing welcome letters in Japanese to include in their goodie bags. To my surprise, half a year was all it had taken to forget the kanji. Given that all I knew about them in the first place was what they looked like and an English definition, admittedly, there hadn’t really been much to forget. I decided to follow WaniKani because I wanted to try a more guided approach to the kanji, and WK also taught two or three vocab words alongside every one. July 2016: Stopped WaniKani I left the US for Japan again and volunteered during the summer; no reliable internet access meant no WK. I’d gone much slower, due to WK’s pacing, and learned vocab words for ~600 kanji over the course of the spring semester. I didn’t re-learn to write, but I felt good about WK. Oct 2016: Graded Readers The semester began at my 2nd Japanese university, I took a placement test and the results confused my teachers. My score on the vocab test suggested that I go into class level 5 of 7; N3, preparing for N2. My reading/listening/grammar/vocab scores suggested I go into level 2 or 3, N5/N4 courses. It turned out that while I had forgotten how to write characters from memory, I still recognized many characters. I recalled the meaning to enough of these characters that I tested above my level. I ended up being placed in level 4, was directed to a stack of White Rabbit graded readers and told to read as much as I could. Hopefully my confidence with kanji could support my other skills. Naturally a reader, I really liked this approach. I read all of the White Rabbit graded readers (N5 through N2) in addition to both of the Read Real Japanese books: Essays and Fiction Feb 2017: The First Book I spread out the graded readers so that I’d finish them by the end of the semester. Upon finishing I began reading Black Fairy Tale by Otsuichi, keeping track of the new words I felt were important enough to write down. By the end of the book I had over 500. Slow and painstaking, but satisfying. (Already linked, but I kept track of everything I read and wrote a post about it). From this point on, I have basically just read books. September 2017: Re-learning to write the kanji I went to Russia to teach English for a year after graduating, spending ~3 hours a day in a train. Having already done RTK once and having done ⅓ of WaniKani, I proceeded to spend ~250 hours over the course of another year working through RTK again. I don’t think it was very useful. May 2018: Onto Mandarin Page 40 I moved to Taiwan, began studying Mandarin and basically left Japanese behind. I still read in Japanese and listen to a Japanese podcast on the way to work, but not much else. I don’t feel I’ve significantly improved from this point: I’m more comfortable with what I have, but not “better.” Dec 2019: In Reflection I spent nearly 1,000 hours on kanji over my first 5 years and that was complete overkill. I have to read a lot of scribbled Mandarin for my current job, so it hasn’t been a total waste, but I think I’d be further along with Japanese if I’d spent 700 of those hours doing literally anything else. Kanji: Discussion Many arguments over how to best learn kanji seem to boil down to a few points: 1. Should you, or should you not, learn to write kanji by hand? If so, how? 2. Should you, or should you not, learn readings as you go? If so, how? 3. Should you focus on kanji, or focus on learning vocab alongside the kanji? 4. Should you learn kanji at once, before other studies, or as you go? I’d like to share my opinion on these points so that you can better understand why I suggest approaching the characters as I have. Spending some time to figure out where you personally stand on each one will help you choose a kanji resource that better aligns with your values. On Learning to Handwrite Kanji Learn to write the kanji, but spread the burden of doing so out over time. Over a long time. Knowing how to write kanji has been incredibly useful for me and I regret zero seconds of the time I spent learning to do so. To be honest, I enjoyed it. That being said, if I had to do it again, I don’t think I’d put so much effort into learning to write them right away. Here’s why: 1. The method that most ardently promotes learning to write the kanji by hand (ie, the one I followed) was first published in 1977. Smart phones didn’t exist then. There was no convenient way to look up a kanji you were shaky on or didn’t recognize, and if you didn’t recognize a kanji, how could you look up an unknown word using that kanji? The answer is slowly. Getting all the characters down pat before really beginning to engage with Japanese would have saved you some massive headaches in 1977. It’s 2020 now. We have cellphones. 2. There’s a phenomenon called Character Amnesia, first documented in Japan in the 80’s, in which native speakers have been becoming increasingly less able to handwrite characters. There’s even an idiom for it in Mandarin: 提筆忘字 (loosely speaking: lift pen, forget character). I’ve personally lived in both Japan and Taiwan and assure you that you could very easily get around without knowing how to write characters from memory—there are very few real-world situations where you couldn’t just quickly look them up on your phone. Page 41 The can of worms I’m hesitating to open here is that, in our ever digitizing world, the ability to handwrite characters just might be less relevant and important than it was at the time the guy who wrote that book wrote it, as much as I love him and his book. I think it’s more practical to reach a point where you can recognize them quickly and then spread out the burden of learning to write them over time. On Learning Readings with the Kanji Learn readings via vocab, not via kanji. Whether you learn kanji first and vocab later or learn both at the same time is up to you. Just make sure you aren’t attaching arbitrary readings to isolated kanji. The Japanese system of kanji pronunciation is incredibly convoluted. Almost all kanji have more than one reading and many kanji have several. 生 has like 12 readings, for example, and just look at 日曜日 (nichiyoubi). The same kanji (日), within the same word, gets read in two different ways. On top of that, it still has 3 other ways that it could be pronounced. Even if you were to have memorized all of these readings, you wouldn’t know which one to use when. This mayhem is partly due to the fact that Japanese people didn’t invent kanji—they took them from China and imposed them upon the Japanese language. This lead to a few issues: ● In addition to whatever [Chinese] word the character originally belonged to, Japanese often also had its own equivalent word. Both got kept. This led to the necessity of having two reading systems, one [Chinese] and one Japanese, the On’Yomi and Kun’Yomi. As a rule of thumb: If you see kanji and hiragana together, you’ll use kun’yomi. If you see multiple kanji stuck together, you’ll use on’yomi... But: ● While Japanese borrowed kanji from [Chinese], Chinese isn’t a language. It’s an entire language family: there are tons of Chinese languages. Mandarin is currently deemed to be the standard one, but this wasn’t always the case. Japanese had been borrowing kanji from China and tacking them onto Japanese words over a long period of time, and this led to borrowing readings from multiple different Chinese languages. There are actually multiple different categories of on’yomi. Here’s a much more eloquently put explanation about that: how Japan overloaded Chinese characters (6min) by NativLang, a linguist on YouTube. ● See sljfaq, imabi (part II) and Tofugu and Wikipedia for more on the history of Kanji On Learning Kanji and Vocab Make your own decision about this. It doesn’t really matter in the end. Page 42 There are two main stances on this issue that tend to go back and forth: 1. We need to take in a lot of new information—the sounds of Japanese, the kana they’re associated with, Japanese words, and the kanji associated with those words. That’s too much to do at once. We should simplify the process by dividing and conquering. 2. We’re trying to learn Japanese, not fancy symbols for English words. It’s inefficient to learn a kanji without a vocab word to go alongside it. Furthermore, it’s practically useless to learn a kanji that you may never, ever use (there are a lot of kanji for specific types of trees and stuff like that). We should ensure that all of our learning is practical. I think both of these positions have valid points that can be demonstrated by literally just looking at random words. Here’s one that means clear/obvious: 明白 (めいはく). 1. If you were to follow approach #1 (the RTK approach), you’d see this and think “bright + white”, but that doesn’t really help you to understand what this means. It makes some sense after you see the translation, but you’ll be thrown off until you look it up. This sort of thing happens quite often. Several of RTK’s keywords don’t end up being super practical beyond making mnemonics. There’s a lot left to do after finishing RTK, to put it mildly. 2. If you were to follow approach #2 (most other approaches) and make a point of learning vocab alongside each kanji, this word would probably look like a great candidate! Being able to say that something is clear or obvious is important. But there are more common ways to express this in Japanese, like はっきり or 当たり前. Unfortunately, you won’t know that until you start engaging with Japanese. While this approach does help you learn the readings, it isn’t foolproof, either. You’re still left with a lot to do after the fact. In a nutshell: ● ● ● Approach #1 will get you through the kanji faster but leave you with a lot of backtracking. Approach #2 will take more time but also take you further along the kanji journey. Whichever approach you use, you’re going to have to spend a lot of time consolidating a dictionary when you begin reading. The endgame of both methods is, essentially, a different starting point for your ability to engage with written Japanese in any meaningful capacity. To be honest, I think the most important criteria in determining your ideal method is (a) patience and (b) tolerance for ambiguity. ● ● If you don’t mind having to (constantly) check a dictionary when you begin reading, RTK will allow you to get into Japanese content more quickly than approach #2. If you want to have a smoother transition into native materials—you know, so you can enjoy them—any of the other approaches I’ve shared will better prepare you to do so. Page 43 You know yourself. As Steve Kaufman says, pick your own solution. On when to learn the kanji RTK suggests working through all of the kanji before you do anything else in Japanese; lots of people think that is a ridiculous suggestion. I agree. Sort of. ● ● Approaching Japanese without having to worry about the kanji will give you a huge leg up with your learning. It makes literally everything easier, I dare say incomparably so. A lot of kanji, even the “everyday use” characters, don’t really show up all that often. If you get through 3,000 kanji before you crack open your first textbook, you’ll be sitting on a ton of very advanced kanji that you won’t see for years, if ever. You’ll forget them and just end up having to re-learn them again later on, effectively wasting your time both now and later. TL;DR After spending way too much time trying way too many approaches, my opinion is that kanji should be approached as part of a routine, worked through in small doses every day, and that you’re better off sticking to your method than jumping ship a few times. So choose your method wisely. The only exception I would make is to say that particularly dedicated learners (those willing to put several hours a day into this over the course of a few months) might find it worthwhile to power through a core base of the most common kanji. After getting through this base, I would still tone things down and focus on sustainability and consistency. Language is a marathon, not a sprint. Finishing any of these kanji methods brings you to a position that I think is comparable to that of an English speaker beginning to learn a romance language, just much more watered down. ● You’re still at zero, in that you don’t understand the language, but now you’re at an optimistic zero. Japanese looks familiar to you, whereas before it was squiggly lines. In other words, after hundreds of hours of kanji, you approach a French learner’s day zero. Sort of. ○ Just as an English speaker could guess the meaning of organización or fenomenal, you can occasionally recognize words on sight, like 消火器 (fire/put out/utensil=fire extinguisher) or 赤血球 (red/blood/ball=red blood cell) ○ Just like an English speaker’s pattern recognition occasionally leads them astray, as with embarazada meaning pregnant, not embarrassed, you’ll also see words like 大 家 (big + house) and come up with something that doesn’t mean landlord. ○ More often than not, you’ll have to look up words even if the kanji make sense. Page 44 The silver lining is that Japanese front-loads the vocabulary burden whereas English back-loads it. After 5 years I rarely see a kanji I don’t know, a fact that makes remembering new vocab very easy. I can’t say the same for English, even though it’s my native language. Grammar Source: u/yep_fate_eos on r/LanguageLearning Page 45 Grammar Discussion: What’s a forest and why are we spending so much time here? Before we begin talking about Japanese grammar, I want to take a page to think about learning grammar in general. It never goes away, so let’s avoid making trouble that isn’t necessary. On consuming information in general There’s a really cool book called How to Read a Book that offers a few obvious, but important, ideas. (Great summary from Ali Abdaal) ● ● ● ● Catching a ball is as much an [active] activity as pitching or hitting it [is]. → Whenever you consume new information, you should be trying to categorize it, figuring out how it relates to what you already know. Reading/studying is an active activity. The art of catching is the skill of catching every kind of pitch — fastballs and curves, changeups and knucklers. → Not all materials are equally relevant/important to us at a given time. Understand what you want to get out of a material and approach it accordingly. Writers vary, just as pitchers do. Some writers have excellent “control”; they know exactly what they want to convey, and they convey it precisely and accurately. [Others don’t].→ No resource or tutor is perfect; you’re going to need to put in a bit of effort meeting them halfway. Reading is a complex activity, just as writing is. It consists of a large number of separate acts, all of which must be performed in a good reading. The person who can perform more of them is better able to read. → Sound familiar? Kolb’s stages of development. It’s everywhere. On the necessity of “multiple passes” Anyhow, what I really want to say is that you should expect to have to approach the same grammar points multiple times and from a variety of angles before they really sink in. Consider this: ...Like a cubist painting (II), whose various elements are related simply by contiguity, novels like Ulysses or The Sound and the Fury can be understood only when they are perceived 'all at once,' for the various elements unfold not chronologically but in a fashion that seems at first to be almost random. It is often said that you cannot read such novels for the first time unless you have already read them. In other words, you must have their facts and their stories in your head (as you would when looking at a painting) before you can understand them as their narratives unfold. ~ Essentials of the Theory of Fiction by Michael J. Hoffman & Patrick D. Murphy I think that the same thing can be said about learning grammar: You can't learn a bit of grammar for the first time unless you already know it. As I said in the beginning of this document, I think that the mustard seed anecdote is a great way to think about learning. If you’ve never seen a grammar point before, its basic function is going to be more important to you than its nuance. As you get a better Page 46 grasp on that grammar point and many others, it becomes easier to appreciate the fine details. I think that this process looks something like this: 1. There is a building and it appears to have four floors. I have located the front door. On the first pass we are just seeing what exists; what is and isn't possible. You aren’t worrying about committing it to memory, let alone mastering it. All we’re concerned about is becoming very loosely aware of the corral that we’ve got to run around in. 2. If I get hungry, there’s a ramen shop located on floor two. “Give me a ramen, please.” Over the course of the next few passes we begin accumulating key structures and “go-to” patterns that we can repurpose for ourselves. We aren’t very concerned about all the little details yet; we’re just picking up some conversational connectors and key structures that enable us to communicate. Speech is possible at this stage, but stilted and formulaic. Hungry? Ramen, floor two. Thirsty? Cafe, floor three. Bathroom? Floor one. Bed? Floor four. 3. What kind of ramen? Shio, tonkotsu, shoyu, miso…. Maybe a tsukemen? Sky’s the limit. Eventually you’ll reach a point where you have a means to express whatever’s on your mind, however choppy or roundabout it might be. From there, you’ll become interested in variations of these common structures for nuance and also begin splicing together multiple simple sentences into one more complex sentence. It helps to know how and when to do so. I think this is a process that will come naturally after getting lots of input. At first you’ll be content knowing that ~が早いか and ~や否や both mean “almost immediately upon/after ~”, which is true, but eventually you’ll find yourself curious as to why the hell there are two structures for seemingly the same thing. Does the JLPT exist just to torment poor learners? Boom, suddenly grammar resources have become useful and you’ve joined the dark side. 4. Pescatarians can’t eat ramen because the broth is pork based, even if there’s no meat chunks. People don’t like grammar because there are a lot of seemingly dumb rules to be memorized: why do intransitive verbs take が, not を? Well, knowing a bit about transitivity, direct objects and agents helps make sense of that, but alone doesn’t teach you Japanese. Just like with the above step, I think there’s also a point in which you’ll begin seeing value in learning about not only Japanese linguistics/grammar but also grammar/linguistic concepts in general. It can be really useful to have an outside frame of reference on Japanese. What’s important is that you see a need to do this. We’ve got Google, so there is zero point in having knowledge just for the sake of it. If you don’t see a point in doing so, don’t learn it right now. As you work through Genki, and as you get further along down the road, remember which “pass” you’re on and think about what sort of info seems valuable. What does will change over time. You don’t need to learn every little thing at once. It’s great to know that one use of を is to mark the accusative case, but it’s probably more useful to know that you tack it onto the food you want to eat. Page 47 Grammar Homework I’m one of those weird people who loves grammar. To me, grammar is a means of self-expression… and interesting. Grammar is the stuff that allows you to show other people what’s going on in your head. It’s what allows you to talk and communicate—and as you can see, I clearly like to talk. A lot. Having said that, I’ll also be the first to admit that it’s easy to waste time going down a rabbit hole. Furthermore, no matter how well you prepare, your first conversations are going to be sort of rough. Everybody has heard of that guy who passed the N1 but can’t hold a conversation. I don’t want you to be that guy. To speak well, you need to speak—but before you can speak, you need to have some sort of grounding in the language. It doesn’t have to be an incredibly firm grounding, but you’ve got to have something to stand on. Mustard seeds and stuff. Level I and II: Grammar-centered, consumption hopeful I believe that languages should be lived, so the “mandatory” section of this guide contains only the bare minimum that I think you’ll need to stumble through native content. I don’t mean to say that you’ll now be able to understand that content (you probably won’t), but rather that you’ll have learned enough to figure out why you don’t understand. If you can figure out why you don’t understand something, you can Google around to resolve your issue. In other words, you’ll have become self-sufficient. So long as you continue enjoying yourself in Japanese, whether or not you’re seriously studying, you’ll improve. That’s a cool place to be, and it’s closer than you think. These stages are all about finding your shoes. Once you do so, you can run away if you want. Level III, IV, V and VI : Consumption-centered, routine grammar refinements Now, I think that input and grammar have a sort of cyclical relationship. You learn grammar so you can consume stuff, you consume stuff and get a feel for lots of grammar points by osmosis. Eventually it becomes useful to backtrack through the fuzz and feeling to check a grammar resource; you’ll figure out some nuance and it’s a super cool aha! moment. Then you go back to input with more precision, depth and ease of understanding than you had before. And so forth. What’s important to me is that, at this stage, the grammar resources are no longer a meaty daily task—they’re a quick warmup that you check in with. At this point most of your time should be going into input and immersion; the resources I talk about in level IV-VI are part of a process of gradually honing your comprehension. You can only cram so much into your head at once, so for the sake of efficiency and sanity, I think this should be stretched out over a longer period of time. Those stages are about revision, routine and exploration. They’ll become increasingly personal. // conjugation-practice program Page 48 Level I: There’s a forest. It’s leaves are, to the best of my understandably shaky knowledge, green. Or maybe they’re blue. Japanese is considered to be one of the most difficult languages for English speakers to learn, and after five years and four languages, I think this difficulty comes down to familiarity—or rather, an utter lack of familiarity. (Don’t be discouraged by this—I actually had a much less painful experience with Japanese than Spanish because I had more motivation and better resources. Difficulty is very subjective.) While I’ve personally enjoyed it more, Japanese has taken much more work than Spanish. This is because there are tons of parallels that you can immediately draw upon when you learn a language that’s close to your native one. Consider the following sentences: 1. I want to go to the sea today because the weather is nice. 2. Quiero ir al mar hoy porque el tiempo es estupendo. 3. 今日は天気がいいから、海に行きたいです。 The English and Spanish sentences line up nearly perfectly, and this is a huge advantage. The English and Japanese lines, on the other hand, don’t match at all. ● ● ● It’s easy to draw parallels between English and Spanish content when you’re consuming, from structures to vocab, enabling you to learn a ton of stuff sheerly by osmosis. See it, recognize it, start using it. Very little conscious effort is required. If you aren’t sure how to express something in Spanish when speaking, you can nearly always just translate word-for-word from English. Even if it isn’t the most natural sentence, it will almost definitely be intelligible. That doesn’t work in Japanese. You aren’t really beginning from zero when you’re learning a language that’s close to your native one. You’ve got similar looking legos and they’re more or less in the right place already. When you learn Japanese, you’ve got to cast all your linguistic legos, print them, then re-draw the blueprints for whatever it is that you want to build. That in mind, I’d like you to spend an hour or so taking a survey of Japanese as a whole before we get into grammar. I want you to understand the major differences between Japanese and English and, generally, to understand what you’re getting into. I think that understanding this will help you to avoid frustration when you get stuck and also to better diagnose problems you run into later on. P.S. I also speak Spanish. I’ve talked at a bit more length on my experience learning to read in Spanish vs Japanese in another comment. If you’re curious about the role that positive language transfer plays in learning, or just aren’t sold on it, please also see that comment. Page 49 Please work through the following before moving onto level II: 1. 80/20 Japanese: Check out the graphics comparing English and Japanese word order. You can read the whole thing if you want, but if not, ctrl+f and read the following sections Defining Different Roles, Defining roles in English, and Defining roles in Japanese. 2. Imabi: Notice how all bubbles in the above graphic are all around the central “English” bubble but mostly left of the central “Japanese” bubble? Read the sections on Left-Branching, Basic Word Order, Omission, and Agglutination. 3. Smile Nihongo: Imabi is great, but it can be dense. Read this much more accessible article on sentence order that comes with nice visuals. If you’re sick of reading, you can watch this (sort of corny) video instead. 4. Japanese Professor: You’ve now covered some of the major things you’ll need to get your head around. Now that you’re familiar with them, read this article that nicely sums everything up. 5. JapanesePod 101: If you’re feeling adventurous, skim through some of these sentence structure comparisons. You don’t need to really understand everything that’s going on - just look at the romanizations and compare where parts of the sentence are. I want you to begin like this because, as you’re learning, some things aren’t going to be clear. In other cases the examples in your textbook will be clear, but you won’t feel like they’re thorough enough: Yeah, ok I get that it works like X, but does this structure also work like Y and Z ? — questions for which there won’t be a clarification. You’ll have to seek clarification on your own. There are going to be times where you feel dumb because seemingly simple stuff doesn’t stick (I got hung up for more than an hour on the fourth lesson in Genki, a lesson that basically teaches you how to use ‘s (apostrophe s / possessive case) in Japanese). You aren’t dumb. This isn’t only you; it’s everyone. It’s okay to feel frustrated. Japanese is hard. It’s a very logical language, but unfortunately, it wasn’t built on the sort of logic you’re used to working with. You’ll have to figure out all this stuff from zero, and from time to time, that’s going to make you feel like a baby. But it’ll get easier as you go. When you’re ready, move onto Level II. It’s time to begin with Japanese grammar. Page 50 Level II: Starting to see the forest for the trees (at least, they look like trees) You might have caught onto this by now, but I’m big on starting small and building a routine. If you improve 1% each day for a year, you’ll end up 37% better off than you are right now. As James Clear, the author of Atomic Habits says, success is the product of daily habits, not once-in-a-lifetime transformations. You’ll finish Genki (or whatever textbook you use) eventually, and if we can physically carve a space out for it in your life, we can then fill that space back in with whatever it is you decide to do after Genki. And so forth. Eventually you’ll put together a well-tailored routine such that, so long as you wake up, you’ll be improving in Japanese. I get that this is exciting and you want to dive into Japanese, but take a breather for a second. There are only 137 sections in all of Genki I and Genki II. Do one per weekday and you’ll be done in about 6 months. That’s what most Japanese university courses accomplish in 3-4 semesters. Humor me and take six months to get through Genki. Doing so gives us the time to get through the first pass of kanji and almost all the way through the 2,000 most frequently occurring vocab words. That gives you all you need to start stumbling through native content—not too shabby, right? 1. Purchase your textbooks. I assume you’ll be using the following: Genki I: Textbook / Workbook | Genki II: Textbook / Workbook If you’re not in a position to buy the books, try out these free resources: Tae Kim | Sakubi | Imabi | Irodori | Yomimono | Beginning Japanese | TYJ | Marugoto → I don’t expect you to take notes, but if you want to, here’s how I do it. 2. Work through one single section per day. To be clear, I mean that I want you to do numbers today, time tomorrow and telephone numbers the day after that. Etc. It might help to watch the content being presented or check out different explanations ( I / II / III / etc) 3. Complete workbook sections on a one week delay. To be clear, I mean to say that you won’t touch the workbook for week one. After week one, you’ll begin completing the workbook sections one week after you’ve completed the corresponding textbook section. I want you to do this to take advantage of the forgetting curve and serial-position effect that is discussed in the appendix section on learning. Waiting a week will force you to struggle a bit recalling the information which will help you to build stronger memories. Page 51 4. Take Saturday and Sunday off. Put the time you would have spent on Genki doing anything else related to Japanese. Explore YouTube or something. Building a backlist of content to immerse in now will make your life easier when we start focusing on input. Level III: I swear to the melon-pan sama that there were trees here... If you’re reading this now, you’ve likely just finished Genki II. Congrats! I also have a sneaking suspicion that if you were to look at that Genki syllabus again, you’d probably feel slightly disheartened by how much of it you don’t feel confident about. Maybe you’re shaky on a few sentence constructions, or maybe the concept of transitive/intransitive verbs went straight over your head. That’s okay. I forgot, too. That’s why we have Level III. This is the place where we figure out where the gaps are and fill them in. This looks like a lot of stuff, and it will take ~5 months, but it should not be time consuming. It should only take 10-20 minutes to finish each day’s tasks, so it’s easy to squeeze in somewhere. 1. Read this post on habit triggers by James Clear and Trigger-Action Plans by Less Wrong. One of my big goals is that, by the time you’ve worked through this book, Japanese will have come to have a tangible and undeniable place in your everyday life. I think that the easiest way to do this is to piggy-back Japanese onto unavoidable parts of your schedule. Figure out a place you can reliably shoehorn Japanese into your day. 2. Pick up Shin Kanzen Master’s N4 Grammar review book. This book is broken into 58 topical two-page units that you’ll progress through at a pace of one per day. The left page has grammatical explanations/sample sentences, the right page has practice questions. There is a review test every 5 units—skip these for now, start working through them once you finish the book. Again, this delay is to milk the forgetting curve for all its worth. 3. Once you finish, pick up Shin Kanzen Master’s N4 Reading Comprehension book. My personal opinion is that this is the book all of your studies have been leading up to. This book will test if you’re actually comfortable enough with the Genki grammar to make sense of Japanese text—again, do one per day. 4. Once you finish, try taking a JLPT N4 mock test. See how you do. I personally never bothered with the JLPT, and don’t necessarily expect you to, but hey, milestones are cool. You’ve now got a pretty solid foundation—enough that you can start working through stuff independently. Give Input - Level I a shot. If it’s too difficult, or you’re just a person who likes structure / doesn’t mind textbooks, come back for Grammar - Level IV. Page 52 P.S. - I think that you’ll get the N5 content down just by working through Genki and beginning to consume content, but if you don’t feel prepared for N4, start with Tankobon’s N5/N4 prep book to make sure you’ve got all your bases covered and then ease into the SKM N4 books afterwards. Level IV: Golly gee, there are bushes amongst the trees! Do not begin this section until you’ve spent a bit of time in the input section. You might be surprised what you can pick up by immersion, so spend a bit of time inadvertently floating around and see what turns up before coming back to this more structured and intentional learning. You can probably pick up a lot of this stuff for free by doing so, so why work harder than you need to? I personally stopped almost all structured learning after Genki II and began reading stuff. I began working through JLPT prep books after reading Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, my second book by Murakami Haruki, and discovered that I had become familiar with all of the grammar in Shinkanzen Master’s N3/N2 books and about half of what was in the N1 book just by reading and looking up stuff as a I went over the course of a dozen books or so. But… If you really like the structure, here are a few textbooks options: Post Genki II, the more conventional route: 1. An Integrated Approach to Intermediate Japanese, popularly dubbed as “Genki III” 2. After Genki III, start working through Tobira: Gateway to Advanced Japanese The books I personally used after Genki II (curriculum at my Japanese University) 1. J Bridge to Intermediate Japanese 2. Chuukyuu wo Manabou 56 3. Chuukyuu wo Manabou 83 (can’t find link?) (Again, I didn’t really follow textbooks after Genki, so I’m not sure what to recommend. I’ll continue to update this as people PM me their recommendations). Do the same as you did with Genki; work through one grammar point per day, be consistent. Page 53 Level V: Having emerged from a wall of bushes, I found even more trees This is like Level III, but for levels N3/N2/N1. A few things: ● ● ● ● Referring back to the “Multiple Passes” concept from the discussion, I think this type of stuff is most efficient for finding and filling in gaps. I worked through the below resources after encountering them in textbooks/the wild and after I already had an idea of how they were used. This stage is about consolidating knowledge and comparing similar grammar. Referring back to the “forgetting curve” from Day 0, this is not content you should binge or cram. You’ll learn most efficiently if you do a bit, consistently, each day. Referring back to “action triggers” from Level 3, I think it’s easiest to be consistent with these studies if you tie them into another thing you do each day. I personally treat them as a warmup; it takes me ~10 minutes per day to do, and I do it first thing after getting to work. It took me about a year to work through a grammar workbook/reading comprehension workbook for N3, N2 and N1. I’ve started again, from N5, because I still find stuff to learn. So, continuing where you left off with N4: 1. I made a comment detailing workbooks I’ve used from several different brands. If you don’t already have a series, click through it and pick the one that looks best to you. 2. Start with an N3 grammar workbook 3. Move onto an N3 reading comprehension book upon finishing 4. Repeat steps 2 and 3 for N2/N1 5. If you feel like you did really poorly, or are running into all sorts of new information, work through another book for your JLPT level from a different brand before going up a level. If you plan on using Shin Kanzen Master for grammar, I’d like to say: 1. I think these books are better used for reference than review. They give a lot of information, and it’s good information, but it’s also organized by topic. You’ll see several grammar points that mean the same thing, just with a slightly different nuance. This is excellent for comparison, but I don’t think it’s a very good first-resource. Unless you’ve already got a strong grasp on the grammar points, I don’t think it’s very conducive to reviewing. Page 54 2. Because it’s so thorough, I’ve got a special routine that I use specifically for the SKM grammar books. You don’t have to follow it if you don’t want to, but please skim through it so you can see what’s going through my head and why I approach them this way. I’d like to get an imgur gallery up that includes the covers of books, their table of contents, a sample practice test and answer key. That being said, all of my books are Mandarin versions, not English ones. If you happen to have copies of any of the books I mention in that comment, please let me know. Then, these are my two favorite workbooks (N5/N4 /N3+) but there isn’t an English version. Level VI: You might not believe this, but trees have roots At this point, if you aren’t yet sick of grammar, I think it would be beneficial to learn more about theoretical linguistics and how grammar works in general. This sort of general knowledge can often help give some sense of meaning to what might otherwise seem like arbitrary rules and distinctions. If you’re interested in learning languages other than Japanese, this sort of knowledge will also help you to take what you learn here and apply it to your new language. For example, consider the following sentence: 葉っぱが落ちている はっぱがおちている Depending on the context, this single sentence may have two meanings: 1. Leaves are falling 2. Leaves are (sitting on the ground) This has to do with something called verbal aspect (in more detail). You probably know that there are different parts of speech (ie, nouns and verbs) and you might have heard of some complicated terminology like modal verbs or verb participles. That’s just scratching the surface, though! There’s actually a ton of different ways to discuss verbs (and all of the other parts of speech). In this case, a difference exists because there are two “different” 落ちる’s at play, so to speak. 1. One 落ちる is functioning as a dynamic verb of achievement. In this case, ~ている indicates that the action is still in progress. Leaves are falling. 2. The other 落ちる is functioning as a static verb. In this case, ~ている indicates that there has been a change of state (not fallen>fallen) that is persistent. Page 55 I recommend you pick a topic you’re interested in and, at a point in time where doing so seems useful to you, find a relevant Wikipedia entry. Read it, then start working through the listed references and Googling around. Vocabulary You’ve stuck with me for over 50 pages, I’m shocked. Word, man. (terrible pun absolutely intended). I’ve pushed vocabulary off for another week for two main reasons: ● ● This is enough time to get through the first chapter of Genki, so you can now start playing a little bit with the words you learn. Vocab is more fun when you can use it. I believe the factor which will most affect your success in this early stage is how consistently you stick to your learning schedule, whatever it is. I don’t want to overload you. Page 56 Vocabulary Homework This section is going to be a bit funky. On one hand, there’s not a lot to say about vocabulary: Keep adding pennies to the stack and eventually you’ll have a dollar. Three dollars or so buys you a freshly baked melon pan. Melon pan is good. On the other hand, there is a lot to say about communication and how we use all of that vocabulary. Language isn’t math; learning lots of grammar points and vocab words isn’t enough to sound natural. As Matt vs Japan says (in that video): Human language is highly specific in entirely unpredictable ways. One aspect of this is that different languages express the same ideas in entirely different ways. [ie, English speakers “play” the piano -- Japanese speakers “pluck” the piano]... different languages also regularly express different ideas in the first place. A corollary concept to this is that native speakers tend to express common ideas via arbitrary, set phrases. There’s no real rhyme or reason to this; they’re just arbitrary set phrases, except native speakers almost always express these ideas in the same way with the exact same words in the same order every time. It’s not a creative process, it’s just set in stone. If your strategy when speaking a foreign language is to essentially think in your native language and then use grammar rules & vocabulary to translate those thoughts into the target language -- best case scenario, you’ll be understood but sound a bit weird. Worse case, you won’t be understood at all. That in mind, I’ve got two main goals in this section: ● ● Talk about how you can acquire the Japanese words you’ll need to do… well, anything Talk about some of the problems that you’ll run into with this “math” approach Page 57 ● Talk about why the input section is important: it’s where you figure out what a Japanese person would say in a given scenario or in response to a given stimulus, rather than just using Japanese words to express English ideas (that will likely come off as unnatural). First, please read this article. It is one of the most useful things I’ve read about language learning. // This part of the document was one of the first I wrote. I didn’t intend for it to be shared publicly at the time, it was just a place where I kept my thoughts in a nutshell and compiled important links to save me time when I had to write about the topic. I realize that it’s rough. While I’m satisfied with the essays in the discussion, in V2 the first section will receive a significant overhaul that will hopefully make it both more scannable and more actionable. For the time being, please bear with me -- and as always, feel free to send a message if it’s clear as mud and you’re stuck. Level I: Intentional Learning & The Construction of a Vocabulary Core I believe that the best way to build a strong vocabulary is to immerse a lot, particularly by reading or listening to books. Writing is an intentional and prepared presentation of language that gives authors all the time they need to use what they feel are exactly the right words in exactly the right fashion; we just don’t drop words like assiduous or perennial in everyday speech. As someone who reads above all for pleasure, I also believe that it’s a major headache to force your way through content that’s above your level, and at this stage of the game, pretty much everything is above your level. That in mind, we’ll first learn just enough vocab to make reading become tolerable. That’s where Anki comes in. Basic Anki 1. Download Anki and figure out how it works (less detail/more detail) 2. Download the Core2k deck and import it into your Anki. Unfortunately, this deck doesn’t line up well with RTK; you’ll run into many new kanji. Learn the word now, the kanji later. (Alternative: JLPT Tango N5 + JLPT Tango N4 have color-coded pitch accent) 3. Adjust Anki to have the deck give you 11 new cards per day; you’ll finish in 182 days To get more out of your time on Anki / if you’re interested in pitch accent 4. Download the MIA Japanese addon 5. Following Matt’s instructions, you’ve got a few things to do: → Use the active fields feature to inject MIA Japanese’s javascript into the Core 2k deck, or → Convert the Core 2k note type to the MIA Japanese note type // will update later. For the time being, please refer to the step-by- step guide that I’ve included in the appendix. There are screenshots of what I do at each step. → Mass generate furigana and pitch accent for each card. This will add furigana to all of The kanji and also color-code each word to show what its pitch accent pattern is. If you like MIA or Anki, you might also be interested in MIA’s addon morphman (II) 6. I personally like low-key anki, also from MIA Page 58 7. If you’re at a higher level, you can use Nayr’s Core 5000 instead of the Core 2000. The sentences in this deck are slightly longer and use more advanced grammar. From Matt: Human brains are hardwired for color. If every time you see the word がくせい (student) it’s blue, you’ll unconsciously associate it with blueness. Blue means heiban in my system, and if you know that, then you’ve just memorized this word’s pitch accent. You’ll memorize some accents “for free” over time. Level II: Natural Acquisition & The Construction of Lexical Associations While there’s a lifetime worth of words and concepts to learn in Japanese, or any language, there is only a finite amount of language contained within any given piece of Japanese media. The average adult native speaker of English might know up to 40,000 words or so, but there are less than 6,200 unique words in the first book of Harry Potter. That’s a pretty massive difference, and good for us. It means that you are much closer to being able to consume a given piece of content in Japanese than you are to mastering Japanese. You can give yourself an easier time by doing two things: ● ● Going out of your way to find shorter content. Less total words = less unique words. Focusing on vanilla/slice-of-life content that doesn’t call for many unique/technical words. Given how few words you need to consume something like NHK Easy News or Harry Potter compared to how many words a Japanese person would actually know, I think this makes a good transition point. I intentionally learn/cram words until I reach a point in which consuming some sort of content is possible. After that point, I begin focusing on input and learning more organically. That’s a cool point to reach and, ultimately, is where I’m hoping to take you. Here’s how: 1. The sentences in your Core 2000 cards are where we start. Never mind 6,200 words for Harry Potter, your first reading tasks will start from 5 or 6 words in length (Anki sentences). 2. You’ll eventually (quite soon!) be able to move on to actual Japanese. Here’s a few options: NHK Easy News | Matcha | Watanoc | Satori Reader | LingQ’s Mini Stories | Other NHK 3. When you’re feeling confident with the above content, start reading for real. Here’s a blog post where I discuss all the books I read from graded content to Murakami Haruki. The “right” time to move on will differ from person to person because it depends on: Page 59 1. How well you tolerate ambiguity, as not everything will make sense right away 2. How patient you are, as due to this ambiguity, you’ll be Googling lots of stuff I don’t think there’s really a right or wrong time; everybody is different. I do think that most people wait longer than necessary to begin immersing, but that’s part of learning how to learn. You can make your progress more tangible by mining sentences to use with Anki (part II). If you don’t, you’ll forget most words you look up and thus have to look them up again later. That being said, you can only look the same word up so many times; eventually, it sticks. I’m happy repeatedly looking up words because I enjoy reading much, much more than grinding on Anki. You do you. Level III: Cramming & Important but Low-Frequency Vocabulary While I don’t personally enjoy using Anki, learning a language involves lots of memorization. I personally chose to take potentially a less efficient but (for me) more enjoyable approach to vocab: I read. A lot. In the beginning, reading was less about the story and more about exposing myself to new vocab and grammar/sentence structures. That being said, I still make regular use of Anki. There’s some stuff that just must be memorized, and for that stuff, nothing beats Anki. If you’re interested in how your usage of Anki might change over time, here’s how I personally use it today: 1. Pitch Accent I didn’t learn about pitch accent until I was comfortable reading Murakami. I didn’t feel like the opportunity cost of learning accents was worth it for a long time, so I didn’t. I instead spent time learning about how it worked, figuring I’d pick it up over time if I understood it. A couple months ago, I discovered MIA’s addon, MIA Japanese. Personally speaking, it’s been a game changer. I used a random deck of Japanese sentences, ran them through MIA Japanese’s addon to color code the words by their accent, and I’m slowly memorizing the pitches of common words. It’s pretty quick going, as I already know all the words/grammar. 2. Specific/technical vocab I spent two years in Japan during university, and during my second year, I took a psychology gen-ed that was conducted in Japanese. I used Anki to memorize lots of specific vocabulary words for different parts of the brain; stuff that was important for class but I didn’t feel I could expect to learn via conversations or reading stuff for fun. Anki is great for cramming technical vocab that you might need, for whatever reason. Page 60 3. Sentences mined from stuff I’m reading As I mentioned earlier, I make quite a few notes in books while reading. If I stumble into unknown words, a useful sentence structure or just a beautiful line, it gets tagged with a number and noted in the margin. I find that a fair bit of this gets committed to memory over the course of the book, but if I really want to remember something, it goes into Anki. In other words, I think that Anki is sort of like an insurance policy. You’d probably be fine without it, and the stuff that you do forget probably won’t really get in your way… but just to be sure, when it comes to the things you’re particularly concerned about, there’s Anki. Vocabulary Discussion The three levels I’ve proposed for this vocabulary section are rooted in the way I feel about a number of important issues related to language and our memory. I’d like to walk through a number of them so that it’ll be easier to find out where we do and don’t agree with each other. Many of these topics are interrelated, so it might be better to think of these as being section headers for one cohesive idea (the homework levels I laid out), rather than a random list of topics. We’ll talk about the following things: 1. Learning vs Acquisition: The “stages” of language acquisition 2. The “Nope” Threshold: How many words you need to learn 3. Beyond Anki: Why even native speakers must take literature classes 4. Circumlocutions: The superpower you get from monolingual dictionaries 5. The Arcane: Memory palaces and “obscure” memorization techniques Mortimer J. Adler on vocabulary and communication: If the author uses a word in one meaning, and the reader reads it in another, words have passed between them, but they have not come to terms. Where there is unresolved ambiguity in communication, there is no communication, or at best it must be incomplete. (ch10) // 5 things a 4x memory champion learned while memorizing 2,000 words in 90 days // Page 61 Learning vs Acquisition: The “stages” of language acquisition The way that you interact with Japanese, including how you approach vocabulary/grammar/etc, will change over time. I think that there are, loosely speaking, three stages: intentional learning, organic acquisition and then fine-tuning. Different knowledge is important at each stage. The levels I proposed in the homework section were inspired by a video from Steven Kaufman, a polyglot with decades of experience, in which he discusses three stages of language acquisition, his response to a presentation by the linguist Stephen Krashen. Here’s what they mean, to me: 1. Stage One, Intentional Learning A particularly determined learner could jump right into a text, with zero background knowledge, if they really wanted to. They’d spend significantly more time with their noses in a dictionary or grammar resource than in the text itself, as little to nothing on the page would make sense to them, but they could do it. It just wouldn’t be a very fun experience. While anything we consume in the language is just “noise” at this point, as Steve puts it, it is far from being random noise. I’ve suggested you start with Anki because I believe that spending some time to intentionally pre-learn the most frequently occuring of these noises will save you enough dictionary-time to make the “nope” threshold more reachable. Where the threshold falls, exactly, will differ from person to person. Wherever it is, though: - Before this point, reading is such a burden that we “nope” out of any sort of immersion - After this point, while still a burden, reading/immersion will have become tolerable 2. Stage Two, Organic Acquisition There are countless words that we could need to know, but unless you’ve got the know-how to parse all of the material you want to consume, it’s difficult to know when you’ll need them. That in mind, I believe we should only intentionally learn what we can confidently expect we’ll need to know, no matter what we consume. Anki helps us to do this. In other words, Anki is not a silver bullet. Some knowledge, like collocative meaning or pragmatics, can only be obtained by immersing in the language. Anki can teach you only Page 62 what you know you don’t know, but you’ll more often be inhibited by the things that you don’t know you don’t know, which we’ll discuss in the sections on comprehension + anki. 3. Stage Three, Fine Tuning: While Anki isn’t perfect, it’s excellent at what it does: helping you to remember the stuff you make a conscious decision to remember. Some things occur so rarely (particular names or especially striking lines) that we won’t remember them unless we choose to do so. See also: Learning vs Acquisition | Stephen Krashen on Language Acquisition | The Role of SRS The “Nope” Threshold: How many words do you need to learn? The first set of 1,000 words offers you over 250x more “coverage” than the 10th set of 1,000 words does. That in mind, you probably want to approach your first and tenth set of 1,000 words differently. You’ve likely heard that 1,000 most frequently occurring words make up ~79% of a given text, or something like that. While the exact words that first thousand is comprised of and how far they'll take you differs a bit from text to text—Netflix subtitles, economic newspaper articles and YA fantasy books are not made equally—there’s a definite pattern to be observed here. It looks something like this: ● The first 1,000 words yields ~78% coverage of vocabulary in a given text ● The second 1,000 words yields ~86% coverage ● The third 1,000 words yields ~90% coverage ● The fourth 1,000 words yields ~92% coverage ● From 5,000, each additional 1,000 words yields less than 1% additional coverage ● From 10,000, each additional 1,000 words yields mere tenths of percent additional coveragehttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/234651421_Unknown_Vocabulary_De nsity_and_Reading_Comprehension We get a few coverage points from proper nouns that aren’t on these lists, so we actually only need ~5,000 words to hit 95% coverage. A language like French has 27% lexical similarity with English, further reducing the amount of words you need to learn. Japanese, unfortunately, has close to none. In other words, if French learners begin their studies at “square zero”, Japanese learners start at “square [negative number]”. In other words, it isn’t just you. Anyhow, on coverage vs comprehension: ● At 80% vocabulary coverage, zero of 66 students could pass a reading comprehension test ● At 90-95% coverage, students begin passing the test, but most still fail. ● A 98% coverage... [seems necessary for dictionary-less comprehension of a fiction text] Page 63 This is somewhat oversimplified, so go ahead and read actual papers (like this one) if you’re really interested in this sort of thing, but I’m basically trying to demonstrate four things: 1. Here’s what 80% comprehension feels like. I’m confident you want more than this. 2. The first few thousand words give you that ~80% text-coverage, but 3. If you want to consume any sort of real content, you’ll definitely need more than that (p24 discussion) 4. 95% coverage means 1 in 20 words is unknown. The average length of a sentence in Harry Potter 1 is 12 words, so you’ll encounter an unknown word every other sentence. Ultimately, no matter how many words you memorize, you’ll still run into trouble when you begin reading. That being said, there is a threshold of words at which you’ll be running into little enough trouble as to find your immersion tolerable. I refer to this as the “nope” threshold. I believe that we should intentionally learn vocabulary until this point, and then focus on organic acquisition after reaching it. As we keep immersing, tolerable will eventually become more and more enjoyable. Beyond Anki: Why native speakers must take literature classes According to the Brown Corpus, the word “the” accounts for 7% of English text. If you were to delete all words except “the”, however, you would understand not 7% of the message being conveyed but 0%. Vocabulary coverage does not equal comprehension, so at some point, you must go beyond Anki. Does knowing 6,000 most common Japanese words mean understanding Japanese? I don’t think so. For one, from where did this frequency list come from? The language of an economic newspaper article, Harry Potter and everyday speech is not the same. In other words, the 2,000 words you learn might not necessarily be the ones that you need to understand what you're trying to read. More often than not, you'll find yourself reading Mad Libs: enough vocab to understand the structure of what's being discussed, not enough to understand what is being discussed. Again with the power law distribution, long-tail words are disproportionately valuable for comprehension. Continuing on, you only need to learn 135 words to familiarize yourself with 50% of modern English text (modern being 1961). That being said, being able to identify 50% of the words used in a text doesn’t enable you to distil 50% of that text’s meaning. This holds true as we increase our word counts, too. After all, quipped a Japanese professor, Japanese people can all read, so why in the hell must Japanese students take Japanese literature classes at university? His answer, in so many words, is that comprehension is a multi-dimensional thing. We engage with language on many levels, big and small, and the level of isolated, individual words (ie, anki) is only one such level. Reading, says this professor, is carefully examining the surface of something (a text), and from what you see, trying to discern what lies underneath it; to understand what lies at its core. Let’s take a brief overview of some of these levels, again referencing Van Doren & Adler’s book: ● Basic orthography: Can you connect the correct sounds to the correct kana? Page 64 ● ● ● ● ● ● Individual words: Can you follow a string of phonemes or kana well enough to recognize a Japanese word as being Japanese? Know its translation? Understand a simple sentence? Kanji: Can you recognize a kanji when you see it? Can you associate a kanji with the phonetic and semantic information tied to it? Do you know what words a kanji is associated with? Between words: Words don’t exist in a vacuum, so you can’t really know a word without also knowing all the words connected to it. You don’t know densha just by knowing train (cool resources: JP / EN); you also need to know that trains run, rather than sliding or rolling. Around words: Words exist in vast inter-related families. For example, vehicle + train have a relationship of hypernym + hyponym; train and plane have a paradigmatic relationship. Grammar: Grammar is what tells you how words are related to each other, or in other words, the sigmatic relationships between words. Like words, there are also relationships between grammar points: when you hear if, do you not expect to later hear then? Sentences: If you understand the words being used in a sentence and the grammar that’s connecting them, you can think on the level of phrases, clauses and sentences. Can you keep track of the flow of sentences, putting this one in context of the last one? At this point, you’ve established a “surface level understanding” of Japanese; given familiarity with the words and grammar, you can understand what is being said. That being said, when dealing with longer texts, you might not understand why it was said. Up until this point, we’ve been reading at an elementary level: we are merely concerned with what is sitting on the surface, what the author is literally saying. (see p7; ch2 “the levels of reading”). You may find that you get vocab right in Anki, but can’t use it in a real conversation. It’s a spectrum. After this point we get into analytical reading. It takes a much higher level of understanding to succinctly explain the function of a paragraph or the point of an entire book than it does to follow a command or make sense of an isolated sentence. ● ● ● Paragraphs: Sentences work together to build stuff. Can you follow their flow well enough to understand the purpose of a given paragraph? Why did the author include it? Essays or chapters: Paragraphs come together to establish the spokes of an argument or to progress the plot.Why did the editor think this one was so important they didn’t cut it? Texts: People don’t write books for no reason. Can you explain, in one sentence, the point of this book? What was the author most trying to say? Like words, books don’t exist in isolation, either. We can keep going with this: synoptical reading. ● ● Authors: What makes a Murakami book a Murakami? What tropes do we find in his stories? What do his main characters have in common? We can talk about a lot of stuff. Genres: What makes a romance a romance? How does this particular book conform or subvert the expectations we have of a [genre] of novel? Page 65 ● ● ● Periods: What makes a 1971 horror story like The Exorcist different from an earlier one, like H.P. Lovecraft’s 1928 The Dunwich Horror or the 2014 Bird Box? How are they similar? Cultures: Although they both involve scary creatures in a dark house, what separates a US film like Lights Out or The Exorcist from a Japanese one like The Grudge or The Ring? Movements: Authors of the same zeitgeist will share many influences; how does a modern novel differ from a postmodern novel? Anybody with a basic understanding of the language can explain a sentence by using a single sentence (in our case, that’s what we’re doing in Anki) but not everybody can paraphrase a paragraph into a sentence. Fewer still can explain the function of a chapter in a sentence, and very few readers can explain an entire book in a sentence. It’s very easy to read without understanding, hence even Japanese people need to take Japanese literature classes—and, ultimately, while you’ll eventually need to move beyond Anki if you want to reach any real level of proficiency. Circumlocution: The superpower you get from monolingual dictionaries Circumlocutions are phrases that circle around a specific word without directly using it; definitions in a dictionary, for example, are circumlocutory. A dictionary uses words you do know to explain words you don’t know. If you can do the same thing, you gain significant freedom in communication. A problem that comes with learning vocabulary is that not all words are created equal. ● ● ● The word not is an incredibly valuable word: it basically doubles the amount of ideas you can express. If you know not and cold, you can express the idea of hot, too. The word giraffe is not a very valuable word. Whereas the word not is generative and continues creating value as your vocabulary grows, a giraffe is just a giraffe. Many words are sort of useful because they can be used for metaphors. Take the word coffee, for example. If you don’t know the word inspiration, you could describe something as being coffee for my life and the person you’re talking to would get the idea. It gives you energy. Placing words in these sorts of mental hierarchies is an integral part of deciding which vocabulary to learn. Ideally, the words you’re learning at any given time are ones that (a) unlock the most degrees of freedom or (b) solve a concrete problem you’re trying to deal with. ● ● Another valuable word is want. If you know want and not, you can automatically express four ideas with any verb you learn. Modal verbs are great to know, too. The word penicillin is pretty specific, but it’s very important to me, personally. My life literally depends on my doctor knowing that I am allergic to it. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to know how useful a word is before you look it up. Say you come across the word (海馬)状隆起 in Japanese, for example. If you’ve gotten through the kanji section already, you’ll see it and think “sea… horse… status quo… humps… rouse…,” then lament that you’ve wasted your time* when you plug it into a dictionary and see that it means hippocampus. Page 66 Hippocampus is, unfortunately, not a very useful word. I learned it three years ago when I took a psychology gen ed in Japan and I haven’t used it since; it’s a giraffe. If you looked this word up on a Japanese-English dictionary, you’ll have just lost three seconds of your life. You are almost certainly going to forget this word before you get the opportunity to use it, if you ever do. The Benefits of a Monolingual Dictionary That being said, your time wouldn’t have been wasted if you’d used a Japanese-Japanese dictionary instead. The fact that you’re probably not going to drop 海馬状隆起 in a conversation anytime soon doesn’t change, but you make up for this loss by getting exposed to a variety of important structures and vocabulary that you well could use in your next conversation. See Weblio's definition of hippocampus: 大脳の古皮質に属する部位で、欲求・本能・自律神経などのはたらきとその制御を行う。 Located in the cerebral paleocortex, [it] facilitates the working and regulation of our desires, instincts and the autonomic nervous system. Something like that brings you more value than the one word translation that is hippocampus ● ● ● ● ● ● It’s reading practice that’s got a much lower bar for entry than novels or blog articles A ten word definition offers much more clarity than a one word translation. If you translated the word 制御 from above then you’d see that it translates to control… but what sort of control? Is it positive or negative? Is it control as in regulate, direct, manage, oversee, restrain, guide, dominate, rule over, govern, influence, handle, manipulate, or suppress? You get a lot of juicy information about word associations that a translation lacks Consuming a lot of definitions helps you to master the structures that Japanese employs to explain things. You can repurpose them for your own purposes in a conversation. By nature, a dictionary explains complicated words with more basic ones. While hippocampus is probably useless to you, words like desire, such as or [location] aren’t. Less tangibly speaking, the ability to make sense of complicated Japanese by using simpler Japanese means you’re becoming independent: that’s a cool feeling. Some reservations While I think that everybody should strive to make the monolingual transition as soon as possible, as Matt vs Japan calls it, I don’t think it’s practical to do right away or in all scenarios. ● ● Some foundational knowledge is necessary. If you don’t know the words located, control, instinct or desire, you’ll also have to look up those words. You can quickly find yourself clicking through a dozen words and grammar points if you start too easily. Some words (particularly nouns) just don’t lend themselves to definition. Take the word pine, for example: any of a genus (Pinus of the family Pinaceae, the pine family) of coniferous Page 67 evergreen trees that have slender elongated needles and include some valuable timber trees and ornamentals. That’s a mouthful in English, nevermind my bothering in Japanese. Steps to transition, even at a low level 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Look up the translation of your word in question Look up the same word in a monolingual dictionary See if you can make sense of the definition, knowing what it’s describing If not, look up translations of unknown words in the monolingual definition If you’re still confused, Google around to figure out the grammar that is confusing you Eventually, start skipping step one. Read the definition, then check if your guess was right. When you’re comfortable with that, start using a monolingual dictionary for step 4. Ultimately, circumlocutions are the difference between being silent and saying uhh.. That thing that hockey players wear on their heads when you don’t know the word helmet. Big improvement! On memorizing stuff // I need to heavily revamp this. For now, start with this video by a 4x memory champion // Memorizing anything basically entails linking something you wish to remember to something that’s firmly rooted in your memory and easily accessible. Several approaches to doing that which are more creative than a flashcard. While they’re not for everyone, you might as well give them a shot. A caveat I want to preface this section with something that’s going to come off as being very contradictory: I make zero effort to intentionally remember the vast majority of all vocabulary I come across. As the guy behind Drawabox explains from 17:47-18:50 of his video on drawing lines: 1. There is one particular angle where you can most easily draw excellent lines—for right handed people, it extends from left to right and away from your body at a 45° angle 2. Many other lines exist: vertical lines and ones that go instead from right to left 3. Ideally, you’d be able to confidently draw great lines from every possible angle, but 4. It’s not worth taking the time to learn to make all of these lines right now: a. There are bigger fish to fry, especially considering that you could just rotate your paper. Developing other skills will allow you to progress faster. b. You will gradually get better at making many different lines over time just by drawing. It’s a waste of time to grind out those skills right now, out of the context of a piece of art, because you’ll pick them up for free along the way. My experience learning languages has been absolutely parallel: 1. For whatever reason, some words stick with zero effort. 2. Tens of thousands of words exist Page 68 3. The more words you know off the top of your head, the less time you spend in a dictionary while immersing and the more precisely you can express yourself in speech/writing 4. It’s not really worth taking the time to memorize all, or even most, of them right now a. Of all the things that might possibly show up in your next conversation, surgical operation or buddhist temple probably won’t. But they’re included in the Core 2k. b. You will gradually memorize a ton of words over time, just by engaging with Japanese, so I want you to spend more time in Japanese than in flash cards. I say the vast majority and not all for two reasons: 1. Some words are incredibly useful and could realistically come up in your next conversation. 2. Some words are just cool, beautiful or feel unique to you. The only time I’ve ever used 花吹 雪 (hanafubuki; sakura blossoms fluttering in the wind as if they were flakes of snow) is when somebody asked me what my favorite word was… but I went out and learned it anyway because I think it’s beautiful and would be disappointed if I forgot it and never saw it again. I’d like you to keep this in mind as you work through the Core 2k. As I expanded on in a comment, so far as I’m concerned, the point of this is not learning the 2,000 most frequently occuring words in the Asahi Shimbun. Going back to the above entry Beyond Anki, there are multiple levels in which you can engage with a Japanese text. ● ● ● To understand a single word, you’ve got to connect characters to sounds a concept or English translation To understand a single sentence, you’ve just got to know the words in the sentence and what sort of grammatical relationships exist between them. There are difficult sentences, but the amount of problems you need to overcome are very limited. To understand a chapter, you’ve got to keep track of many sentences and how they relate to one another. We’re no longer dealing with sentences in isolation, we’re dealing with this sentence on top of those sentences. The same sentence could mean many things, depending on what precedes it. We’re dealing with much more complex stuff now! For me, the Core 2k is the simplest reading practice you can obtain with Japanese. Once you’re comfortable parsing the five or six word sentences contained in the Core 2k, you can start working on parsing the longer sentences in resources like Match Easy JP, NHK easy news, Satori Reader or Tadoku. While reading through content in resources like these you’ll be exposed to all of these words, and if you don’t know them, you’ll have to look them up. Eventually you’ll get sick of looking it up and your brain sort of goes alright, alright, I’ll remember the damned thing. I want you to learn, not to suffer. To that end, I want you to save your energy memorizing the truly important stuff you need to know now or figuring out the stuff that’s stumping you. No sense wasting your energy on stuff you’ll naturally acquire for free along the way. Page 69 But anyhow, for the stuff you deem it worthy to memorize: Pictures: we don’t always need a translation As anyone who has tried using a monolingual dictionary has found out, some types of words lend themselves to definition more easily than others. Red: of a colour at the end of the spectrum next to orange and opposite violet Pinecone: the conical or rounded woody fruit of a pine tree, with scales which open to release the seeds. These definitions aren’t incredibly helpful if you don’t already have the technical knowledge necessary to understand light’s refraction or a big enough vocabulary to know words like conical or scale. In contrast, they’re things you’d recognize immediately if you saw them, even if you didn’t have an English word for them. A big part of Fluent-Forever’s first steps involve connecting forweign words to concrete images -akai to a red background, not the word red. Here’s how Gabriel goes about doing so. Memory Palaces: we might as well take advantage of evolution I can’t remember what I had for breakfast yesterday or which words I underlined in Kafka on the Shore an hour and a half ago, but I can close my eyes and walk the halls of my elementary school or a childhood friend’s house with surprising ease. Humans have a pretty incredible memory for spatial layout. People exploit this fact to memorize all sorts of information. In a nutshell, it works like this: 1. Pick your palace—it can be anything spatial. The street layout of your childhood town, your school building or office, your grandma’s house. Just pick some place. 2. Turn the things you’d like to remember into a vivid image. Nelson Dellis, a 4x USA memory champion, describes this process as “see - link - go” 3. Place your images at various physical points in your “palace” 4. When you close your eyes and “walk” your memory palace, arriving at that physical point will trigger your memory, bringing up your image and reminding you of the vocab word. I think this is particularly useful for remembering certain traits about words, like which verbs are transitive and which are intransitive. Create a symbol for transitivity (say, a swiss army knife) and one for intransitivity (say, a pink rabbit) and work it into your see-link-go image. If you’d like to learn more, or give it a shot, check out: ● Fluent in 3 Month’s step-by-step walkthrough ● Nelson Dellis’s book, Remember It! ● Joshua Foer’s book, Moonwalking with Einstein Page 70 GoldList Method Stage Two: Immersion [Just a placeholder for now] Page 71 Page 72 Input Immersing is important; so is thinking about the content you’re immersing in. Page 73 Opening Words First, congratulations. This is a huge milestone, and personally speaking, it's the reason I study languages. This is where Japanese becomes part of you, rather than just something you’re studying; a means to explore your interests and relax, rather than flashcards and textbook problems. It’s also a very ambiguous stage that’s difficult to give any tangible advice about, or really even talk about. As someone who loves reading, I’m personally partial to Stephen Krashen’s Input Hypothesis (in brief)—you might have encountered terms like comprehensible input or i+1 before. Even if not, you’ve likely seen immersion touted as some sort of silver bullet, but it isn’t quite that simple. Dr. Krashen’s work has garnered quite a bit of criticism (more layman friendly; auto-downloads .pdf). While I’m not a linguist and won’t weigh in on these arguments, I think it is important to point out that nobody is saying that input isn’t important. Here are a few random points, paraphrased: ● ● Perhaps not all input needs to be comprehensible. Sometimes incomprehensible input is useful. When we get negative feedback (realizing we don’t understand something), we’re encouraged to learn. In other words, you’re more likely to fill a hole if you know it exists. “Input is the only causative factor driving second language acquisition” is a very strong statement. Even if input is paramount, there are likely other things that contribute, too. I think it’s safe to say that you must consume tons of content. In my personal opinion, though: ● ● ● I feel more comfortable speaking Russian than Japanese, but I got practically no input in Russian and I’ve read ~20,000 pages in Japanese. To learn to speak, you must speak. I think low-pressure feedback that nudges you in the right direction is important. See this post that links to 11 journal articles and TL;DR’s six major linguistic theories on immersion. I think that study is important, as refining your knowledge lets you immerse more efficiently Anyhow, a few general comments that I think are relevant to many people: ● ● ● ● ● ● If you’re comfortable not quite understanding everything and (likely) spending a lot of time in a dictionary or grammar reference, you can start immersing quite early. If not, you can always wait. Learn a bit more first. You’ve got your whole life ahead of you. If you’re not sure if you’re ready, find a few things you’d like to consume and check in once or twice a week. Eventually they will seem doable. At that point, go for it! If you’re nervous, read Tofugu’s article on The First Page Syndrome. Things get easier. Quantity eventually becomes quality. Once you find something you like, do a lot of it. It will be slow going at first, but soon you’ll find yourself drowning in stuff you’d like to consume. YouTube keeps recommending videos that suit your tastes, you find an author or director whose work you want to explore, you randomly stumble into stuff that looks interesting. This is a matter of inertia, and you’ve got to get the ball rolling. Page 74 Start Here Given that Japanese is a skill, it’s not difficult to point out basic fundamentals and say whatever you’re aiming to do, you’ll need to know X, Y and Z. Here’s how you can do that. Now that you’ve got those fundamentals down, however, I can’t confidently say what you (you) need to work on. What you do and don’t need from here on out depends heavily on what you plan to do with Japanese. That in mind, I’ll first introduce a few rules of thumb you can apply to guide yourself. Next, I’ll outline what I did in order to provide examples. This is a framework; make it work for you. Principles—whatever it is that you want to do, I think these things will make your life easier. 1. There are many ways to read a book. Know what you want out of a piece of content before starting and approach it accordingly. ie, extensive reading vs intensive reading. 2. Each author has their own quirks. It’ll be easier to read 10 books by one author you’ve gotten familiar with than 10 books by 10 authors, each of whom you must also get to know. 3. Learn to work with Smart Howard and Dumb Howard (~5:30-6:30). We’re both of these people at different times, and you should understand how to work with each of them. 4. Some work is more taxing than others, and we’re each at our best during a certain part of the day. Figure out when your most productive time is, then apply the 90-90-1 rule. 5. Something that’s hard now will be easier later; go through it then. For now, focus on engaging with content that you can make consistent and significant progress through. Reading—whether you start with reading or listening is up to you. I like reading, so I start with it. 1. Mandatory: Work through stage 1, 2 and 3. This content will benefit everyone. 2. Follow your interests; the order of the remaining stages isn’t necessarily fixed. 3. Consider learning about: Overlearning (II, III); Sentence Mining; The Monolingual Transition Listening—whether you start with reading or listening is up to you. I like reading, so I start with it. 1. Mandatory: Read through the “listening homework” home post where I outline different listening problems; no matter what you’re consuming, you’ll be dealing with this stuff. 2. Follow your interests; I don’t expect you to work through all the levels. I’ve just generally organized the content in terms of categories I feel become progressively more difficult. Output—I’ll talk about this more in the output section, but here’s what I want you to keep in mind for now.. 1. Like most things in language, input and output are not isolated skills. Here’s how I see it: a. Input is like strength training. It expands the boundaries of what you could do. b. Output is like doing yoga. It concerns what you can actually do, and how smoothly. c. In other words, input is your skill ceiling and output is your skill floor. 2. What you can comprehend is always higher than what you can produce. Capitalize on this. a. When outputting, you’ll stumble into stuff that you can’t do / can’t do smoothly. b. When inputting, watch for these “trouble” areas. Before long you’re bound to find a structure, word, fixed phrase, etc, to solve your problem and communicate that idea. Page 75 3. I’ve spoken from day one (RU) and after ~8 years (SP). Both work. See the Output section. Reading Homework As I’ve learned more about writing, the way I look at reading has changed, too. During my junior year of university I received a D+ on an essay I wrote. The professor was kind enough to walk me through the essay, giving me suggestions about how I could have approached it differently for a better grade. It turned out that biology teachers put values on different things than literature professors do. I had a similar experience the first time I wrote a news article, which was supposed to be flat and objective, did product copywriting, which seemed verbose and soulless to me, and submitted the first chapter of a novel I began writing for feedback. Lots of learning curves. In other words: Not all writing is the same. Different types of content are put together differently and pursue different goals. This is really important to understand as a writer, but it’s also important to understand as a reader. Different sorts of content should be approached differently. My goal here is to help you pick content suitable for your level and think about how to approach it. This isn’t a fixed order, it’s just how I did it. I was afraid of length, but not difficulty, so I worked through progressively harder short stories until I felt more confident. You don’t have to do that. You might skip around, skip an entire level, read 20 books in one level compared to my handful. I think that stage 1, 2, and 3 are logical for everyone, but beyond that, this is about you and your interests. If you’re finding it difficult to be the judge, here are a few rules of thumb to apply: ● ● ● If I’m really struggling with a book, I put it down. My experience is that in the time it takes me to struggle through one book, I can enjoy two or three easier ones… and during that time, improve enough to read the thing I originally wanted to read. If I’m really enjoying an author, I stick with them for a while. I read almost everything by the author Otsuichi, a YA horror author, even though I found him to be quite easy. Getting familiar with an author’s style lets you focus on the language issues you struggle with. If I’m changing mediums, I expect to have a more difficult time. Because not all writing is the same, I know I’ll be dealing with different challenges. Reading manga is not the same as reading a novel, a newspaper article, threads on a message board, content in a business email, etc. Each of these formats has their own lingo, structure and learning curve. Page 76 Stage 0: Getting set up I’m going to be up front with you, and this is not an attempt at empty encouragement: These first few steps are some of the hardest ones you will take in Japanese. The obvious fact that you’re still learning Japanese aside, there’s a lot of infrastructure that you’ve got to get in place: - Finding a dictionary you like Until you get better at kanji, looking up words by drawing them is a real hassle Figuring out how to use a Japanese dictionary Figuring out how to deal with stuff you can’t find in a dictionary (Google: [thing] 意味) Figuring out what to do when you don’t understand despite knowing all the vocab/grammar Finding authors you like, finding stuff that’s near your level… or Finding content that’s available in Japanese in the first place (I use Bookwalker) While these things aren’t necessarily difficult, they are very much a hassle and take time. Then, here are a few other things you might want to check out before getting started: ● ● ● u/Shade0000 made a nice post with several resources useful for reading u/Kymus made a post aimed at beginning readers with links to some reading clubs I personally make brief notes about stuff that I think is important while reading. This helps me to minimize interruptions while reading and also minimize stuff that I put into Anki. ● Sentence Mining: By now, you know how you feel about Anki. If you like it, you can get more out of your reading by keeping track of useful sentences that you stumble into. ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ Antimoon: It started with two Polish guys 20+ years ago. See what they have to say. AJATT: Took the concept and ran with it. Khatzumoto on why it’s useful, how to set up flashcards, where to get sentences and what to focus on learning first. Fluent Forever: put it on a spectrum where you start with individual sounds, work through simple noun:image cards and eventually get to sentences. Here’s Gabriel’s thoughts on Japanese specifically and here’s a review/overview of how it works. Refold: Expanded on many of these concepts. Here’s a step-by-step guide from them about how to work it into your routine. Migaku: Created several apps that streamline the process of sentence mining: Migaku Dictionary Addon and Migaku Japanese addon. Animecards has further refined the process, bringing together several tools specifically for making cards from anime Page 77 Stage 1: The Core 2k The vocabulary practice we’ve been doing with the Core 2k doubles as the simplest form of reading practice we can get: while a book or chapter might be too much for now, anyone can get through a single sentence. We’ll build a very basic foundation here, then extend into content that gets gradually longer and gradually more difficult. For the time being, just focus on reading through each sentence. This is reading practice. A lot of the words will work themselves out even if you don’t make a conscious attempt to memorize them. ● ● ● This is about discovery. If you see a new structure, Google around to learn how it works. Feel free to take steps to memorize something that you feel is useful and/or cool You’ll find that you consistently get certain words wrong, for whatever reason. For me, it was 抱く vs 抱える’s pronunciation. Give trouble words a bit more attention: Link and Go. In my opinion, the most important part of this stage is just getting more comfortable seeing Japanese so that you feel more confident when you pick up a page of Japanese text. It can be sort of daunting to pick up a page of unfamiliar squiggles, but it gets easier over time. Stage 2: Graded Readers Eventually you’ll have covered enough fundamental vocab and grammar that reading is a pretty smooth experience where learning happens organically. For example, I recently stumbled into ひい ては while listening to an audiobook. Upon Googling it I found that it’s a JLPT grammar point, so I read a quick explanation of how it works. Now I’ve got a basic idea of what function it serves, and as I continue to see it come up in content I consume, I’ll continue to refine my current understanding. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of vocab and grammar to work through, and that can get pretty overwhelming. For this reason, graded readers are excellent: they’re intentionally written with the needs and capabilities of a certain level of learner in mind. If you pick up an N3-level graded reader, you can be confident that virtually every vocab word and grammar point contained in the book will have been covered by the N3 level. This ensures that your reading practice is as efficient as possible, letting you focus on reinforcing your understanding of the stuff that you’ve just learned about. - Quick tip: Reverso Contexto is an excellent tool to help parse stuff you don’t understand Research on ‘overlearning’ (II) suggests that there is value in continuing to practice even after you understand how something works. Your brain continues to become more efficient at performing a given task, requiring less and less energy to perform it, even after you’ve reached a point where you feel comfortable with it. In other words, you can benefit from extensive reading even if you don’t feel that you’re learning something “new”! Page 78 Here are several resources you can use to get started with. Work through as many or few as you need, and once you feel like your feet are under you and you’re ready for a challenge, move onto the next section. During this stage, you’ll be doing extensive reading (tadoku). Free online stuff ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ~1,800 pages of graded readers (#2, #3)—From N5 to N2 over 5 incremental levels Choco-Choco—A few simple foreign fairy tales written in Japanese Dr. Dru—Simple humorous stories aimed at absolute beginners Ehon—Picture books aimed at children up to 6 years old (sortable by age group) Honbun—Many small essays/posts/confessions organized by JLPT level Hukumusume—Lots of stories aimed at elementary Japanese kids Kano Blog—Short, bilingual blog articles about Japanese culture Gakken (Manga)—Articles about science topics aimed at school kids GakuGram— [pending review] LingQ mini stories—60 stories written in progressively more difficult Japanese Mainichi—Japanese news written for different age groups, ie 6+ or 15+ Matcha—online magazine written in simple Japanese Nihongo Tokuhon—a few (homemade?) low-level graded readers NHK easy news—news articles that have been re-written in simple Japanese Teacher’s Stories—bilingual essays in simple Japanese and English w/ vocab lists Wakari Rekishi—World history, written in “middle school” level language Wasabi—a few simple Japanese fairy tales written in Japanese Watanoc—online magazine with graded articles (I've linked to the N5 section) WithNews + TBS News—(more difficult, but not sure where else to put these) Yahoo! Kids—Many educational articles for JP kids, organized by grade Apps/books - - - 10min readers—graded from "year one" to "year six", topical books that each contain an article/story that the publishers think a Japanese kid of that age should be able to get through in 10 minutes Japanese io—similar to LingQ/Manabi Reader but only available online LingQ and Manabi Reader—apps that let you upload your own materials, or see those prepared by others, which get supplemented by a pop-up dictionary and SRS system. Manabi Reader is free but requires a subscription for SRS/stats; LingQ is $12.99/mo. Minna no Nihongo Graded Readers—One for N5/N4, one for N3 Satori Reader—Several series (horror, romance, everyday life, textbook dialogue, etc) that are written by an in-house Japanese author and professionally voice acted. You can click on each word in the text for a pop up dictionary/grammar explanation. $9/mo; $89/yr.. Page 79 - White Rabbit—Graded readers spanning N5~N2 over several levels. I read the physical books and liked them, but I don’t normally recommend them because of how expensive they are. The app seems to be the same material, just digital and much cheaper. Stage 3: Read Real Japanese: Essays and Fiction + Soseki Project Reflecting on every resource I’ve ever used in six years of studying Japanese, this is what I think I’d deem as being the most useful. All hyperbole aside, they’re worth their weight in gold. Both books follow a similar format: - Right-hand page is a genuine piece of Japanese content from a famous author. The only modification made is that furigana is included for each word’s first occurrence. Left-hand page is a sentence-by-sentence gloss in English. Just enough information to help you work out trouble sentences, not enough to make sense without reading the Japanese. The back-half of the book is a running grammar-dictionary for each story. Every grammar point that wouldn’t be covered in Genki I (ish) gets brought up and explained: what it does, why it’s used here, the nuance it carries over [similar grammar point covered earlier]. In other words, these books are a pair of training wheels. They’ll introduce you to the most important concepts you’ll need to figure out in order to make sense of Japanese writing. In many stages, the book simply says: This is [Y grammar point], and it’s the same as [X grammar point]. The difference is that [X] is used in speech and [Y] is used in writing. As a heads up, this is real Japanese. It’s a step-up in difficulty from the graded-readers you were working through earlier, and you’ll feel it. If you’re coming from the last level, I expect you’re going to get stuck here. Unlike in the last section, this is probably going to be intensive reading for you. Go slowly, make notes of stuff you learn, come back to the grammar explanations from time to time. You might particularly like one of the authors you like—in that case, read more of them, rather than the stuff that I’ve listed! I personally really enjoyed the short story from Otsuichi, so I read several of his books. I’ve included a few in stage 6, 7 and 10. The Soseki Project is similar, but not quite as thorough in terms of explanations (it’s made for free by one person), and aims to “make the works of Natsume Soseki more accessible to learners of Japanese. All of the texts are narrated; many words (and some tricky phrases) can be moused over for a loose translation. I The content in Soseki Project is more difficult, but if you don’t want to pay for the above resource (or even if you do!), I recommend spending some time with this website. Page 80 Stage 4: Manga As I said in the beginning of this section, each different style of writing comes with its own conventions. Each one is easier in some ways and more difficult in other ways. When I think of Manga, here is the key benefit and the key pain-point that sticks out to me: - - Manga includes pictures, meaning the author can use pictures to set scenes and show the action rather than relying on words and exposition. This serves to greatly reduce the grammar/vocab barrier needed to tell a story. For this reason, manga/web comics have a significantly lower barrier of entry for reading than that of novels/essays/etc. Manga is mostly dialogue, which can be good and bad. On the one hand, there is a lot of slang/casual grammar structures/character tropes that you might not be familiar with. On the other hand, depending on the genre of manga you’re reading, you can be more confident that you’ll run into stuff you could actually use in a conversation. That in mind, here are a few things to get you started (please help me update this list!): - A Beginner’s Guide to Manga and Types of Manga A comment listing several free/partially-free and legal online options A spreadsheet with several manga (and other) recs, organized by difficulty (original) Crystal Hunters(reddit link)—if you know 87 words, you can get through this manga Matcha Manga—a free manga series discussing common mistakes learners make N5/N4 Manga Recommendations Pixiv Comics—Amateur? Manga online. Newest/oldest chapters of each manga are free. 五等分の花嫁—Recommended by someone who just passed the N3 We’ve officially left behind the “learner materials” and moved onto “real” Japanese. Understandably, the difficulty of a given manga can vary considerably. You should know the difference between intensive reading and extensive reading (tadoku) by now, so as you approach each new manga, take a few minutes to skim the language and decide which style of reading to employ. (I didn’t actually read manga when I began Japanese, but I read quite a few webcomics in Mandarin. I think that experience was valuable, especially in the visual context it gave me to understand how certain exclamations ‘feel’. If I could go back in time, I’d read a few manga in Japanese, too) Stage 5: Aoi Tori + Tsubasa Bunko // I wasn’t quite sure where to put this, so I’m sticking it here for now Aoi Tori Bunko (II) is a publisher that puts out books aimed at an elementary audience. Here’s a quick introduction. They’re real books, aimed at Japanese people, but intentionally written with simpler language. Additionally, all of the text is in a larger font and includes furigana. Page 81 There’s also Tsubasa Bunko (II) - here’s a quick introduction. This publisher seems to primarily put out adaptations of anime/light novels and popular YA translated content, with the goal of making them more accessible to a younger audience. The language used will be identical to the “normal” book, but all of the text is in a larger font and includes furigana. If you want to move beyond manga but aren’t quite ready for “real” books, I would start here. - They’re quite cheap, at around 600-700JPY/$5-6 USD per title. - Bookwalker’s mobile app is also great for learners – simply long-press or double tap a word to bring up a dictionary definition. (Thanks u/UnreliableTL) Stage 6: Easier Short Stories Look at you! At this point you’ll start working through pages of pure and genuine Japanese. That might be a little daunting—or at least, I thought it was. For that reason, I began reading on a Kindle. A Kindle gives you a boost that will let you begin reading Japanese books before you’d be able to read a paper one. The ability to just click on a word for a definition makes learning to read in Japanese much less of a hassle. Matt vs Japan has a great video on the topic; also see Rikaichan. I personally would start with these books. They’re very plot heavy (meaning there isn’t a lot of description or subtlety; it’s all about what’s happening), so you can focus on getting through the stories. - - Zoo 1 and Zoo 2 by Otsuichi Very short horror stories aimed at a YA audience (so they aren’t that scary). I wasn’t a horror buff before I got into Japanese, but I really fell in love with the genre: scary is scary, no matter the difficulty of the language used. The books are simple, but still enjoyable (Liked these? Otsuichi has written sev eral books. Check them out!) Kino's Journey (several volumes) by Keiichi Shigusawa (anime) Tons of little stories following the gender-ambiguous Kino as they travel through foreign countries with a sentient motorcycle. Kino stays in each country for only three days, and each time they discover something unique that leads to some philosophical brooding. Stage 7: Slightly Longer Short Stories By this point in time you’re hopefully beginning to feel a bit more comfortable in Japanese. While you might not quite be ready for it, I encourage you to begin thinking about the monolingual transition. Japanese definitions tend to be clearer than one word English approximants, and it’s also a cool feeling to make sense of Japanese you don’t know by using Japanese that you do know. I personally use daijirin, but there are several, including the free online Goo Dictionary. Then, just because you’re using a J-J dictionary doesn’t mean that you’ve got to use it all the time. Try the Japanese dictionary, and if it doesn’t make sense, refer to an E-J dictionary. For example: Page 82 ● ● ● Nouns don’t lend themselves well to description (here’s apple from Merriam Webster, for example: the fleshy, usually rounded red, yellow, or green edible pome fruit of a usually cultivated tree (genus Malus) of the rose family. This is a mouthful even in English.) Sometimes you’ll find a kind of abstract word with a confusing definition In rare cases, the J-J definition won’t be all that helpful (ie, the definition of しつよう in my dictionary is “in a しつこい way”, which doesn’t help you if you don’t know しつこい!) These are similar in difficulty to the stories in the previous section, but more lengthy. - - 失はれる物語 by Otsuichi I would call these stories more bizarre than scary; if you enjoyed Zoo, definitely check this out. The story of a girl who suddenly begins receiving calls on a pretend-telephone, a boy who can absorb or transfer the injuries of others and a mysterious talking plant. キッチン by Banana Yoshimoto Banana comments that her writing concerns “the way terrible experiences shape our life”, and this story involves a girl who moves in with a florist and his transgender mother upon the death of the girl’s grandmother. It’s a touching story of sorrow, love and confusion. Stage 8: Normal short stories This is another step up in difficulty, similar to the one you dealt with when we went from graded readers to short stories. If you’re having trouble with the content, I would personally recommend giving pre-reading sessions a shot: - Run your eyes over the lines of the text without trying to understand anything Make note of unfamiliar vocabulary and grammar points Take some time to look these things up and add them to Anki/etc Read each short story after getting familiar with its key vocab/grammar points Three suggestions for you this time: - - - 女のいない男たち by Murakami Haruki A series of seven unrelated stories all involving men who have either lost an important woman in their life or didn’t have one in the first place. Each one is an adventure, but the first few pages of story #3 are especially difficult. Consider reading #3 last. 死神の精度 by Kōtarō Isaka A compilation of short stories following the day-to-day life of a shinigami tasked with the dead-end job of making sure ethereal spreadsheets line up. In each story he pays a new person a visit and goes about determining whose time has and hasn’t come yet. Short stories and excerpts on Kokokoza Quite a bit of reading content aimed at Japanese MS/HS students. There is a variety of content available for many subjects and from many authors; comprehension questions / discussion questions are often included, too, to help guide your reading. Page 83 Stage 9: Meiji-era Short Stories The stories in this section are all very short, but the language is a significant step up from the stories you’ve read so far. You will struggle and might need to take multiple stabs at these. Having said that, I would like you to give these books a shot for two reasons: - - In the next section the difficulty goes way down, but the stories are about 10x longer than anything I’ve suggested so far, Kitchen aside. I want you to get used to beating your head against these stories so that the next ones feel like a breeze and you can focus on the length. These are some of the most revered authors in Japanese; the story by Natsume Sosheki was described by a professor of modern Japanese literature at my university as being “one of the diamonds of Japan’s literature”. They’re really special, and I hope you enjoy them. So, anyhow, here are four pieces of genuine literature to take a shot at: - - - - 待つ by Dazai Osamu You’ve probably heard of 人間失格 / “No Longer Human”; this is a sort by the same author that’s only a few pages long. A person is sitting at a train station and waiting for someone… but who? Dazai’s writing style is special, and this is personally where I fell in love with him. 高瀬舟 by Mori Ōgai A police escort is taking a prisoner down the Takase river to Osaka during the Edo period. He feels unnerved because this prisoner is quite unlike the others; the story climaxes with the prisoner explaining his crime. The story’s twist is the most shocking one I’ve ever read. 羅生門 by Ryuunosuke Akutagawa A servant, recently discharged, is taking shelter from the rain under an abandoned arch in Kyoto. He’s struggling between two choices: to steal or to starve. He makes to spend the night in a tower with the dead and something happens that leads him to make his choice. 夢十夜 by Natsume Sōseki Ten short stories, each one involving ten different dreams that span from the “age of the gods” to the Meiji era. All of the stories are quite surreal and quite bizarre, each one beginning with the phrase こんな夢を見た: this is what I saw in my dream. Stage 10: Short novels While the language of these books isn’t as difficult as that of the previous ones, that doesn’t mean they’re easy reads. Whereas 待つ by Dazai Osamu was four? pages long, the shortest book in this section is 352. Length adds just as much challenge to a text as difficulty does, in my opinion. My favorite series of books growing up was Pendragon; each book is around 400 pages long and I got through them in a single day. When I read in English, I often feel as if I don’t notice the words on the page. They disappear, and I see the book playing out as if it were plugged into my occipital lobe. Page 84 Needless to say, that didn’t happen with Japanese for a long time. It took me nearly three months to get through that 352 page book, dragging out the pacing way longer than I was used to. Having to look up so many words/grammar points, I also struggled to get into the book and enjoy it. Anyhow, what I want to say is that although these books are easy, they present their own challenges. - - - 暗黒童話 by Otsuichi The book begins with a blind girl being befriended by a talking crow; it pecks out peoples’ eyeballs and presents them to the girl. When she puts them in, she sees glimpses of their life. Most of the story comes from the PoV of a girl named Nami who lost an eye in a freak accident, but gets set up with a transplant… and soon starts seeing unsettling things. (Liked these? Otsuichi has written sev eral books. Check them out!) コンビニ人間 by Sayaka Murata A girl who doesn’t “fit” into society finds her place working in a convenient store, a place where there are explicit rules to govern how all interactions should take place. Despite being an easy read, it’s very powerful and offers an interesting take on social norms and the way we perceive who “we” are. Not necessarily exciting, but thought provoking. (Liked this book? Murata has written several books. Check them out!) ペンギン・ハイウェイ by Tomihiko Morimi I haven’t read this book, either, so I’ll refer you to its wikipedia/goodreads. Again, this book is another common first-read by people getting into Japanese books. Stage 11: Novels w/ Anime The difficulty of these books isn’t that much higher than those of the last section, but they are quite a bit longer. By the end of this section you’ll have gotten through a 1,000 page book in Japanese. You might want to watch the anime before reading the book to help you connect dots while reading. - - - Another by Yukito Ayatsuji (anime) A student transfers to a small inaka town from Tokyo and quickly finds that something strange is going on: everyone, including the teachers, seem to be ignoring the existence of one girl. He begins to befriend her, and shortly afterwards, people begin dying in accidents. 新世界より by Yusuke Kishi (anime) In 2013, a small percentage of humanity gain psychic powers and wreak havoc on the world. Eventually a group takes power and genetically modifies psychics so they’re unable to harm other humans. Toss a subservient group of monster-rats into the mix that are seen as being less than human and you’ve got an interesting story that gives lots of foot for thought. Overlord by Maruyama Kugane (anime) The servers of a super-realistic VR video game shut down, and a person who was logged into the game at the time finds himself literally stuck in the game. He goes looking for answers and to see if there is anyone else—chaos and adventure ensues, 14 novels worth. Page 85 Stage 12: Easier-to-read novels Congrats, you’re at the point where you’re ready to read “real” books in Japanese. I’ll suggest two easier books to get you started, but all of the books by both authors are very readable, so feel free to explore the rest of their works if you feel so inclined. You’ll improve a lot along the way. - - - ノルウェイの森 by Murakami Haruki A very straightforward read and one of Japan’s most famous modern author’s most famous books, Norwegian Wood is a story of love, loss and growing up. While not as surreal as Murami’s other works, it does include a love triangle (square?), two suicides and a student revolution. 重力ピエロ by Kōtarō Isaka Haru and Izumi are two brothers; one cleans graffiti off the streets and another is a detective(?) who gets word that the graffiti precludes acts of arson. Getting to the bottom of the mystery is a violent and emotional roller coaster that makes you think a lot about what “family” means. u/Ripace posted 30 books that they read before taking the N2: Part I and Part II Stage 13: Start Exploring At this point you have enough of a foundation that you should be able to work through most things relatively comfortably. It might not necessarily be a walk in the park, but you’ll have reached a point where you often understand what you see, and if not, have the tools to figure it out (in Japanese). From this point on I suggest that you start exploring your interests and reading widely. Explore new genres, read the wikis of your favorite authors and read the authors that they say influenced them. Maybe you look into pop-science novels, economics books or even poetry. There’s a world of stuff. If you’re feeling lost, here’s a useful post talking about how to find stuff to read in Japanese. Just in case you don’t know what you want to read, here’s a few copy/pastes from another post (II) 3652 by Isaka Kotaro If you chose to read his novels/short stories, you might like peeking into the author’s head via some of the essays he has published about how he sees the world. This is a selection of diary-like reflections written over the course of a decade. If you like these, it seems relatively common for JP authors (I / II). チーズはどこへ消えた? by Spencer Johnson This is a translation from English, but it really took off in Japan. It’s a quirky story about two mice on the perpetual hunt for their cheese, used as a means to put forward a few archetypal perspectives about how we see the world and what that means for how we approach goals. 夏の花 by Tamiki Hara Page 86 To me, one of the most powerful qualities of literature is that it grants us the ability to see the world from someone else’s perspective as they wish we would see it, free from our own biases. In Japan, an entire trove of atomic bomb literature exists; as a US citizen, it’s incredibly sobering to read. 夢をかなえるゾウ by Mizuno Keiya My favorite kind of self help-help book… if you could call it that. It’s kind of a novel. One day a salaryman failing to live up to his own expectations buys some cheap gimmick. It turns out the gimmick summons Ganesh, an Indian deity who for whatever reason speaks heavy kansai-ben. The elephant follows him around giving him everyday suggestions to change his life. It’s great. Really. Listening Homework I’ve learned two particularly important lessons about listening comprehension: 1. Listening is a holistic skill. There are multiple reasons you might not understand something. 2. Skills are interrelated. Getting better at reading also improved my listening comprehension. I discussed this in depth in a post on listening comprehension, and I don’t want to plagiarize myself, but the gist of the post is this: practice does not make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect. I’m sure there are more, but I discuss six reasons you might not understand what you hear: 1. Pronunciation Issues (II): Because you don’t sufficiently understand how Japanese phonemes can mutate and/or how the sounds of spoken Japanese get mapped to written Japanese, your ears provide less reliable information than your eyes (reading) do. 2. Knowledge Issues: Even if you had a pair of perfect ears, you still wouldn't understand everything you heard. You’ve also got to know the word in the first place, the nearby words providing context and the grammatical relationship between all those words. 3. Register Issues (II): Japanese sounds “shift” in fairly predictable ways to become more formal or casual, and until you learn these patterns, you’ll be thrown for a loop when you hear them. There are also common sound shifts that occur in different accents. 4. Processing Issues: Sometimes the issue isn’t that you don’t understand something, just that you can’t process it quickly enough or that you can’t retain all of what you heard. If you can take multiple listens, all of these issues will work themselves out without further aid. 5. Matching Issues: Japanese is a high-context culture (II) and omits parenthetical information; this leads to situations where you understand what’s being said, but you aren’t sure who or what it’s referring to, causing ambiguity. Or you don’t pick up on a key piece of information. 6. Focus Issues: Disappointingly often, I find that I don’t understand something because I’ve been spacing off. Experiment with listening at different times/places or while walking. I also meditate (II / III), and I like it, but I figure you’ve already got your own opinion about it. Page 87 Listening comprehension isn’t a multiple choice test where you’re simply right or wrong. Each of the above issues contributes a bit of blurriness, and if there is too much blurriness, you won’t be able to make out what you’re hearing. (another post with 13 reasons you might have missed something) I personally believe that quantity eventually becomes quality, that a lot of issues will work themselves out with enough time spent listening to stuff, but that’s a longer term solution. If you want to do something beyond simply waiting patiently, diagnose the reason that you don’t understand whatever it is you’re listening to and respond accordingly. No amount of pronunciation training will help if the real issue is that you don’t know what key vocabulary words mean, or that you’re spacing out for a few seconds here and there. Gabriel Wyrner from Fluent Forever goes into a deep-dive on the listening comprehension here. Highlighted items (in below lists) are personal recommendations from me. Stage 0: Reading As odd as it might sound, I feel that reading more was just as important to developing my listening comprehension as actually conversing and listening to content was. - - - - Vocabulary: The most obvious one, a bigger vocabulary helps us to make sense of stuff. When we don’t understand something we tend to go huh? and in the half-second it takes to do that, we also miss the next 3 words that we would have understood if we hadn’t blanked. Associative meaning: I also discussed this in the vocabulary section, but there is much more information associated with any word than merely its translation. As you read more you’ll start picking up on associative meanings that will help you make inferences and connect the dots even when you don’t quite understand everything. Sentence structure: Just like words, grammar points do not exist in isolation. Certain structures tend to go with other structures (ie, if I say “if I could have,” are you surprised to then see “I would have.” ?) With practice, you’ll get a better idea of what structures might come up later in a sentence based on what you hear in the beginning of it. This helps to automate things a bit, letting you direct more focus to whatever you’re struggling with. Overlearning: Not only does your knowledge increase as you consume more content, your brain literally gets more efficient at performing that task/processing that content. I can’t say that it’s a requirement—I’ve only read a single book in Russian, but I feel comfortable conversing in Russian and enjoy watching TV shows/YouTube videos or listening to podcasts all the same. The difference is that I spent a couple thousand hours conversing in Russian to reach that point, a number I’m very far from in Japanese. I guess I mostly just want to underscore the value of reading, and I also think that it’s easier to diagnose the root of your misunderstanding (and thus fix it) while reading than listening. Page 88 Stage 1: The Core 2k I won’t repeat myself here because what I have to say is basically the same as in the reading section. The sentences in the core 2k are isolated (meaning you don’t have to keep track of or process any prior information to understand them, as you would with a novel or TV show), contain only basic grammar and the most common vocabulary words, on top of well articulated and clear audio. From time to time, close your eyes while you do Anki and see if you can understand via audio alone. Stage 2: Random listening and discovery Each level of proficiency comes with its own boons and hurdles, and a particularly annoying hurdle of the beginning stage is that there isn’t all that much you can understand. I personally address this simply by adjusting my expectations and the value I’m expecting to get out of a piece of content: - Discovery, not comprehension: I know that I’m not going to be able to follow whatever it is I’m watching without subtitles. Trying to do so leads to frustration. Instead, I choose to adopt a discovery mindset: I pay attention for useful phrases in the English subtitles and then make a point to listen out for that in the audio. This is a more positive experience. I’m definitely not going to understand the movie, but I can pick out conversational connectors (II) like to tell the truth or that being said that will be useful to me right now. - Mimicking Pronunciation: The fact that you don’t really understand anything puts you in a sort of unique sandbox. Explore it. Review some of the ideas we talked about in the pronunciation/prosody section and just listen for stuff. A big part of our foreign accent is applying patterns from our native language onto Japanese when we shouldn’t be doing so… so this is an opportunity for you to get up front and personal with your preheld notions. Maybe you pay special attention to how someone’s voice changes when they get angry, or perhaps you listen out for K sounds. Are they similar to English? Does something sound off? - The 50% Rule: Less important than that you don’t understand right now is that you will understand someday. The issue is that it’s difficult to know when, exactly, without regularly testing yourself. Just checking in with content from time to time ensures that you don’t end up waiting longer than you actually need to in order to begin your immersion. So, when you feel like it, just explore. Focus on the cool little tidbits you can explore because they add up, and celebrate the stuff that you do understand here and there. Most importantly, keep track of the stuff that you like. One of the biggest advantages you can give your future intermediate self is a treasure trove of content that you’re excited to consume. Page 89 Stage 3: Learning about Japanese… in Japanese You can artificially limit the amount of words you need to know by focusing on content that’s within a very specific area. The more you know what to expect, the easier it will be to follow what you hear. //Immersely looks promising, but I haven’t tried it out yet. 500 YT channels that include hand-made subtitles. - Nihongo no Mori Japanese grammar points get introduced in simple Japanese, with lots of terribly/wonderfully scripted actions to help drive the grammar’s meaning and usage home. Particularly great for someone who knows a bit of Japanese but is struggling to break into audio Japanese content. (However, the playlist I’ve linked to assumes you know nothing). - Ako Japanese //need to review still… Long form videos (~30m) videos about N5-N3 vocab/grammar - Arai Channel for Japanese Study // need to review still… basic (n4/n3) grammar explained in slow, simple Japanese with explanations on a whiteboard and a lot of body language - Benjiro’s Beginner Japanese In each episode Benjiro skypes with someone in Japanese and, on the right side of the screen, he writes down key phrases/vocab you might want to learn. - Comprehensible Japanese Brief presentations entirely in Japanese; they’re aimed at beginners, so the language is simple, and the creator makes clever use of visuals/drawings to provide context clues. If you’re a beginner and nervous about breaking into Japanese content, start here. - Easy-Japanese Audio Books (Shino Sensei) Short stories adapted for the N5/N4 level are read aloud; Japanese text (with furigana) presented in the video alongside translations of key words. Toggleable English subtitles. - Game Gengo A guy picks JLPT grammar points out of Japanese video games – he shows the scene where the grammar point comes up in the game, then breaks down the sentence and explains the grammar points. If you like this, also see GameGrammar. - Learn Japanese Pod Several hosts discuss a variety of scenarios in a “no textbooks allowed” approach. After Page 90 talking in Japanese they break down key sentence structures and present key vocab. - Learn Japanese with Manga Naoto creates a lot of cool content, but I especially like this one that I linked to. He plays through video games, and on the left side of the screen he has taken the time to organize a running grammar/vocab dictionary of the games dialogue so you can learn while watching him play. - Let’s Talk in Japanese A podcast where a Japanese teacher speaks in… Japanese… about a variety of topics. What I think makes this particularly special is that, as a teacher, Tomo is well versed in the JLPT and releases “graded” episodes, from N5 to N1. Episodes are quite short (5-20min) and, in the few that I have listened to, Tomo speaks in very clear and well-articulated Japanese. - Japanese Immersion with Asami A pretty cool example of the natural method in action. In each episode Asami brings a simple story (with pictures) and then builds a story with the student by asking a series of simple questions that build on each other. - JLPT Stories A variety of topical podcasts organized by JLPT level - Minori Japanese // need to review still… simple Japanese grammar (N5/N4) explained (in JP?) - Moshimo Yusuke A guy walks around Japan aiming to show off what Japanese people see in their everyday life. There aren’t a ton of uploaded videos, but his content is quite long and always has bilingual subtitles available. - Onomappu A guy talking about Japanese culture and onomatopoeia in simple Japanese. He’s very upbeat and the videos aren’t dense watches. He speaks very clearly, and most of the videos have handmade captions available in EN/JP/CN. This is a great “first channel”, in my opinion. - Sambon Juku Aimed at low-intermediate learners, Sambon Juku creates a lot of cool videos discussing commonly misused Japanese and/or small expressions you can work into your own speech. He tends to discuss a variety of things in each video, has very clear pronunciation and most of his videos feature simultaneous E/J subs. Page 91 - Seemile Korean | Lingua Club Spanish | Kensuke Uchida Russian There’s a wide variety of content in Japanese teaching the basics of other languages. As only basic grammar/vocab is being taught, you can probably follow quite a bit of it, especially if you know some of the other language! Search for[Japanese name of language] + 基本 or 101. - Wakaru Nihongo Graded “podcasts” for listening comprehension. Each script is read twice, once slowly with key words highlighted on the screen and once at regular pace without subtitles. Each episode closes with a few comprehension questions. - Quite a few more suggestions in this thread, a list of 500+ JP YouTube channels and a thread sharing several podcasts that include transcripts. Stage 4: Slices of Life, Podcasts and Let’s Plays Slice of Life—presentations of everyday life—is a surprisingly popular genre in Japanese. It’s literally just a collection of scenes ( “slices” ) taken from everyday life. This quality makes content of this genre very accessible compared to other types of content. - Shirokuma Cafe An anime about a lazy polar bear who, facing the ire of his mother, goes out in search of a part time job. The anime is chock full of dry humor and centers around the day-to-day adventures of him and the other animals that frequent the cafe. It’s not for everyone… but it’s genuine Japanese, and I found it accessible just after finishing Genki II. - Animal Crossing Let’s Plays As the title suggests, a girl talks while playing Animal Crossing. She does a pretty good job of narrating what she is doing, so this is especially good for covering everyday objects/vocab. - Hikakin Plays Minecraft Hikakin speaks quite quickly and there aren’t subtitles, but everything he says follows what he’s doing in game, so it’s not too bad to follow. There are hundreds of episodes. (I’ve chosen not to list them because I think they’re more difficult, but more gaming channels here) - Japanese Quest A japanese teacher plays video games in Japanese and breaks down the game’s language while playing. He puts keywords at the bottom of the screen. - Learn Japanese with Noriko A daily podcast put out by a Japanese teacher. Each episode is ~7 minutes long, and every day she talks about a random everyday topic. Japanese alcohol, Zoom meetings, lessons from the Tobira textbook. I recommend this as a first “real” podcast. Page 92 - Let’s Learn Japanese from Smalltalk Two Japanese girls studying abroad in the UK have conversations about their experience and contrast life there with the UK. They’ve got a good grasp of what words are difficult and either explain them or translate them. Very accessible, yet engaging, podcast. - Nihongo con Teppei Two podcasts: one for beginners, one for intermediates. Beginner podcast is a bunch of simple questions/answers with a lot of repetition. Intermediate podcast is Teppei talking about a random topic - from chopsticks to space ships. Teppei does a wonderful job of explaining concepts in simple Japanese, and as a language learner himself (EN/SP), he is quite self-aware about which words his audience might not understand. I wish this podcast was around when I began learning. - Sakura Tips A daily podcast by a Japanese girl who speaks very slowly and clearly. Each episode has both Japanese and English transcripts available. She talks about travel, food and Japanese culture. - 4989 American Life A Japanese woman living in the US created a podcast where she talks about her life abroad. It’s not necessarily aimed at learners, but she speaks very clearly and has been writing a transcription of each episode on her blog, so you can simultaneously read and listen! (transcriptions are available starting from episode 89). - //Lots of threads on podcasts, particularly in this thread //Thread about self-help channels on YT Stage 5: Conversations I’ll discuss this in more detail in the following section. Before we get there, though, I’d like to comment that I like to think of conversations as “interactive input” rather than “output”. - During conversations you get the opportunity to get used to a variety of styles of Japanese speech and voice types with a safety net: if you don’t understand something, you can ask! Each conversation is a team-effort in which you work together to communicate about a given topic, so the difficulty level of a conversation will adjust to your level. - A major bonus of conversations is that they very naturally point out the stuff you don’t know, can’t express as comfortably as you’d like to, or maybe that you know but had sort of forgotten about. Once you find something you struggle with, you thus are primed to notice that thing while consuming content. Structures that you could have used to express the idea you failed to express suddenly stick out, enabling you to get a bit more out of your input. Page 93 Stage 6: Vlogs and YouTube Speakers As I suggested earlier and in the last section, you can help make up for your current lack of Japanese by taking steps to ensure that you’re engaging with a restricted amount of Japanese. There is much less unique Japanese in a given video than in Japanese as a whole language. That in mind, you can make things much easier on yourself by following a single person extensively, rather than a wide variety of content. In time you’ll get used to the quirks of that person’s speech and get comfortable with their accent/pace, enabling you to focus less on parsing the speech and more on understanding what’s actually being said. Going from “40 year old office salary man” to “21 year old college girl” is a major adjustment; it’s easier to stay within one persona, at least for now. I’m going to do my best to provide a wide variety of figures. Pick one and keep up with them. - Osha Taigu A Buddhist monk who takes viewer questions / struggles and offers his perspective on them, covering everything from serious topics like happiness and death to lighter ones like lighter ones such making friends or dealing with motivation struggles. He speaks very clearly and quite slowly, and several videos have subtitles. The video I’ve linked to is a practical guide to everyday happiness and literally changed my life. - Aoi’s Channel Aoi posts videos about fashion, makeup and travel. Her videos are shot from the shoulders up so that it looks like you're skyping with her when in full-screen (but mostly shows off her makeup). She is a dynamic speaker and there are no subtitles, but most of the time she is discussing what she’s doing, so you can follow along even without catching everything. - Bell’s Bungaku Bell is a very friendly vlogger who creates videos aimed at people who like to read. Most of her videos are reflections/reviews on stuff she reads or book recommendations, but there’s also a bit of variety/travel content thrown in as well. She speaks very clearly and (I believe) all of her videos have Japanese subtitles. - DN-Ütube A workout progress / lifestyle blog. Though Yosshi’s more recent videos are more traditional and refined, his earlier videos are largely composites of his daily life: working out, walking around Tokyo and partying. He speaks in a pretty rough/masculine way in some older videos, but his recent ones are much more neutral/professional sounding. - Kazu The opposite of Renehiko, Kazu is a Japanese guy documenting his experience living and working in Shanghai. His videos are very active and feature moving shots that he narrates over. This is the most pronounced “lifestyle” blog of everything I’ve listed—you’re literally Page 94 tagging along for his daily life—but the subtitles are in Mandarin and his speech might be a bit hard to understand, though as he’s narrating, you can probably follow along anyway. - LingQ Japanese Podcast ~20 minute podcasts with two Japanese people (host + guest) discuss a variety of topics. The speech is very natural and not “toned down” for learners, but each episode comes with hand-made English and Japanese subtitles, making them good for study. - The Real Japanese Podcast //Have not listened much yet //A Japanese teacher talks about various topics; each podcast includes a JLPT level, so you can gauge the approximate difficulty - Renehiko A german dude living in Japan who (used to) post vlog videos discussing his everyday life in Japan as a foreigner. He’s not a native speaker, there are no subtitles and he speaks quite quickly, but I think that his content is especially relevant for foreigners thinking about living abroad or considering staying in Japan longer term. - Russian Sato Part cooking, part food and part discussion, these videos are about a small girl who consumes large amounts of food (mukbang). She isn’t speaking for the entirety of the video, but most (all?) of her content has subtitles and you’ll learn a ton about food. Plus get hungry. - Tenjou Inue A Japanese guy living (studying) in the US who posts slightly longer form video essays/discussions/reflections on more serious topics: racism, social differences, cultural differences, stuff like that. There are no subtitles but his speech is quite clear. - Yoshihito Kamogashira From McDonald’s Manger to Motivational Speaker, Yoshihito is a very energetic speaker who travels around Japan talking about happiness, motivation, business and generally how to interact with people. Click-baity titles and not the clearest speaker, but he is very enthusiastic and likeable. - Yukiniru A girl who posts a pretty wide variety of content that sometimes consists of her travels, sometimes consists of her personal life and sometimes consists of her dates/going out with friends. Her speech isn’t as clear as Bell’s and there typically aren’t subtitles, but her videos cover a much wider variety of content and give you more chances to get to know her. Page 95 - Yusuke Okawa A designer/photographer who produces very professionally looking blog videos where he talks about his life, photography and also gives users pointers. I think that his speech is much more natural than some of the other guys (he’s not a motivational speaker or a manly man), but there are no subtitles and a lot of the emphasis is on the cinematography. - Several dozen channels listed in this Reddit thread Stage 7: Anime and Educational Content I’m putting this here because, generally speaking, I find anime to be easier to follow than dramas. It could go anywhere—there are some very easy to understand anime (like Shirokuma Cafe above) and then there is also stuff that I can still hardly follow, even with subtitles (like Gintama). I don’t personally watch much anime, but there are tons of recommendation threads, so Google around. As for “educational” channels that I will recommend, I’ve put them here because they cover slightly denser content than the above vlogs and I think are nice preparation for some of the more complex language you’ll hear in audiobooks, discussions and dramas. - Abataro A guy reads non-fiction books and talks about their key points. Tends to focus on business/tech. His speech is relatively clear, but he covers complex content and there is very little in the way of presentation/visuals, so you really have to listen. - Algometry Mini true-crime documentaries (~15 minutes), covering cases from both inside and outside of Japan. Most episodes seem to have English translations available. - Brightside Japan Kind of a pop-science channel; lots of videos about a variety of topics - Gakushiki Salon A guy reads non-fiction books and makes presentations about their key points. Tends to focus on self-improvement, learning and communication; recently he has been branching out into non-book content. Speaks quickly but notes are on screen. - Nakata “University” An enthusiastic dude in a suit and serious whiteboard organizational skills presents lectures on a wide variety of content, covering everything from philosophy to physics to history. He speaks quickly and the content is difficult, but he also regularly asks questions to see if you’re following and follows the notes he has written on the whiteboard very well. Page 96 - NHK for School, try-it and Khan AcademyJP Lots of video lecture content aimed to supplement school children’s (MS/HS) learning and/or break down more complicated topics in a variety of subjects. - Karawaka Rabo A slightly more serious but lower-budget science channel than Brightside Japan. - Saratame San A guy reads non-fiction books and makes presentations about their key points. Tends to focus on self-improvement, pop-psych and history books. The videos are “speed drawn”, so while their aren’t subtitles, you don’t have to rely completely on your ears. - Threads: The first anime you watched without subtitles Stage 8: Dramas and Comedy I haven’t watched a ton of dramas so I’ll only list a few, but if you’re struggling to find stuff you like, I’d recommend following specific actors. Find one thing you like, watch the rest of their stuff. Dialogue in dramas tends to be more difficult than in animes but it’s more realistic, and you can use it to sample the Japanese in different environments: a construction lot vs office vs high school, etc. - DELE In a sort of morbid insurance program, people sign up with a company who offers to ensure that their digital footprint and communications will be totally erased upon their death. The drama follows the ‘new guy’ who is tasked with verifying the death of clients and taking steps to erase their data… but just happens to often get personally involved and take steps to try to do what he feels is the right thing, even if it’s against company policy. - Hana Kimi A girl goes undercover and abroad to transfer to an all-boys highschool in a different country, all in order to get closer to her idol, a track star at the new school. There’s tons of ridiculous trouble that occurs, but it’s quite touching at the same time, concerning a bunch of kids learning to deal with life, their situation and people different from them. - Gomen ne, seishun! A Buddhist boy’s high school and a Catholic Girl’s high school are facing a merger. The drama follows one “test class” who gets merged early and tasked with working together to throw the school’s culture festival… plus some romance and an interwoven backstory where we find that something that happened in the male teacher’s high school days is related to the current situation. It’s over the top but I really enjoyed it. Page 97 - Mr. Hiraagi’s Homeroom Students get called to their homeroom one day, on the top floor and corner of the school, and the teacher announces that he is taking them hostage. He has rigged the school with bombs and threatens to kill students at regular intervals unless his demands are met. There’s a huge twist that I think is predictable if you’re paying attention, but it’s fun. - Shinigami Kun The story follows a shinigami tasked with balancing the ethereal spreadsheets. In each episode he appears to a new person and tells them that they’ll die in three days; some believe him, some don’t. It was fascinating watching the shinigami trying to grapple with the value of life and how different people approach their imminent death. I’m personally a huge fan of Konte/Manzai, a very Japanese style of situational humor that features two people, one more serious and one kind of ridiculous, often in a different role or position that skews their outlook on the situation and leads to a variety of humorous miscommunications. As there are so many different skits, I’ll just link to a particular one that I enjoy. - Baikingu A guy walks into a ramen shop and causes lots of problems. - Tokyo 03 A friend finally explodes after an “accumulation” of small annoyances over time - Anjasshu One guy thinks he’s walking into an interview; the boss thinks he’s dealing with a shoplifter Stage 9: Audiobooks and Native Podcasts Audiobook.jp has a limited (but quickly growing) amount of audiobooks available, and unlike Amazon/Audible, they can be purchased without a Japanese credit card/billing address. I’ll leave you to your own devices, but if you haven’t listened to an audiobook before, I recommend starting with a few easier reads (even if you’re otherwise comfortable reading). - 世界から猫が消えたなら by Genki Kawamura A man dying of terminal cancer is approached by the devil with a deal: he’s gotten permission from God to extend this man’s life by one day per each thing he removes from the world. The touching story details the man’s perspective on how the world changes with each thing removed, and how he deals with the fact that he’ s dying. - 君の膵臓をたべたい by Sumino Yoru (Currently listening to this book, but it’s a pretty easy listen). A high school boy befriends a classmate only to find out she is dying due to issues with her pancreas. The story begins Page 98 with her death, then involves him reflecting on the progression of their friendship and her outlook on dying. If you like this author, the site has several of her books. Stage 10: Multi-Person Discussions While conversations are pretty straightforward because the people you’re talking to will adjust their level to suit you, and vlogs aren’t too hard to follow because one person is talking without being interrupted, even many advanced learners struggle when they find themselves in a situation where they’re stuck in the midst of a discussion with many native speakers at once. - Democracy Times Not-quite-as-long-form (30-45m) videos discussing complex and pressing issues, but typically is a conversation between two people. If you’re struggling with Sakura TV, try this channel first. - Sakura TV Long-form (often multi-hour) discussions on serious issues facing the world and Japan featuring a few regular hosts and some invited experts. Complex topics, a variety of speech styles, no subtitles. You’ve just got to follow the discussion as it bounces around. //bonus (threads I’m saving for later but haven’t gone through yet) ● Any good or entertaining JP youtubers? Output Page 99 brb looking for some picture to represent this section Opening Words While everybody seems to agree that input is important, the mileage varies with output. ● ● Benny Lewis advocates for speaking from day one, and he has documented his experience traveling all over the world to learn as much of various languages as possible in 90 days Dogen seems to advocate for speaking early… but not in a conversational sense. He suggests that learners focus exclusively on pronunciation at first, and an integral part of finding issues with your pronunciation is listening to recordings of yourself speaking. Page 100 ● ● Matt vs Japan thinks that early output is not necessary, and might even be harmful, as a conversation entails expressing ideas you haven’t learned yet, and you may develop bad habits. He thinks that output comes naturally after consuming lots of comprehensible input. Steve Kaufman says that “to speak well, you must speak,” but he doesn’t think you should speak from day one. He consumes lots of input (audio input in particular) until he feels like he has a solid foundation, then begins speaking after a few months/a year when ready (II). All of these learners have seen incredible success, so I think that Luca Lampariello makes a reasonable point when he comments that there are pros and cons to both schools of thought. Personally speaking, I’ve experimented with both extremes. For what it’s worth, I agree with Luca. - Spanish: Studied in MS/HS for 5 years. Listened to a lot of Spanish music. Waited ~ 7 years to have a conversation. At 7 years, I began reading. At ~9 years, I began texting regularly. Japanese: Lived in Japan for 2 years but mostly just read. Didn’t regularly speak till ~year 5. Russian: Had a Russian girlfriend/friend circle; began speaking from day one. I have only read one simple book in Russian and didn’t use a textbook. I learned purely via talking. Mandarin: I took a 1 month crash course in phonetics and then begin teaching, in Mandarin, in a bilingual school. ~2 hours of presentation per day, plus ~30 min conversation per day. I’m not a linguist, but it seems safe to conclude that you can have success with either approach. In my opinion, the “best” answer is going to vary from person to person, depending on their situation. Anecdotally speaking, here are the takeaways from my experiences listed out above: - - Russian is the language that I’ve spoken the most and feel the most comfortable speaking. I often feel disappointed about my ability to speak Japanese, even though it’s the language I can express myself in most precisely. Because I’ve gotten so much input, it’s very clear to me just how foreign and ineloquent my speech is, compared to the things that I’ve read. I get the most praise about Spanish, the language I have the most natural accent in. Taking a month to 80/20 Mandarin pronunciation is one of the best language learning choices I’ve ever made. It significantly smoothed out the early phases of my learning. After tons of conversations, you gain a sense of confidence that people will understand the words that come out of your mouth, which makes the overall experience more comfortable. Start Here I’m not a linguist and have no idea what the literature says, so take this with a grain of salt. Reflecting on where I’m at in my languages, and on the progress of children and adults that I’ve worked with, this is how I think about the “spectrum” of conversational ability. Principles — knowing what to say (idea), knowing how to say it (grammar) and doing so eloquently are different skills 1. On learning to improvise in jazz: why you should play lots of music BADLY Page 101 2. Classical musicians get tons of input but still struggle to improvise (speak). Why is that? (II) Mouthwork — a purely physical process where you get used to stringing together all the Japanese mouth shapes 1. Start with individual kana; go slowly and get comfortable with those shapes a. Goof around. What does it feel like to use more/less air? Very slowly, start with eeee and move it backwards till it becomes ahhhh. What sounds are in the middle? What does it feel like to make a vowel a bit more forwards or a bit more open? 2. Get recordings of individual words. Move onto sentences (ie, in Anki) when you’re ready. 3. Learn a few tongue twisters. If you can do these, everyday speech will be a breeze. Scripting — if you’re really anxious to begin talking, we’ll work to reduce performance anxiety here 1. Write a self introduction in English, have it translated and get a recording. Memorize it. 2. Next, do the same with short content that interests you. I like to memorize music so I can sing along. The only point of this is further practice stringing Japanese sounds together. Early Conversations — our only goal here is to become comfortable with the notion of expressing ideas in Japanese 1. Find a or book an iTalki tutor (II). 2. Stumble. Your only goal is to get through the conversation. Treat this as a game. 3. Keep track of the ideas you don’t know how to express; figure them out as you go. 4. Make a point to practice conjugations, simple sentence structures, etc. 5. Before long, you’ll plateau: there just isn’t much new ground to cover in a daily conversation. Conversations — now that we’ve acclimated to Japanese a bit, we begin working towards more natural speech 1. It’s no longer enough to just talk. Make like a guinea pig and observe your feedback closely. 2. Output mobilizes input. Find stuff you can’t express well, look for answers in your input. 3. Ask your tutors to summarize your ideas; pay attention to how they re-word your speech. 4. The advantage you get from working with a tutor is the ability to ask questions. If you don’t know how to say something, ask! Today I asked mine: how would you say “defines” in what I think really defines the modernistic worldview is… ~と見なす? ~を定義する? ~を認識する? Post-Conversational Fluency — basically, start thinking about how you need to use language in a given situation 1. Get specific. “Google Image - I’m Feeling Lucky”. Describe the img as concisely as possible. 2. Get thematic. Watch a discussion on a specific topic, note key phrases, then try to discuss it. 3. Seek models. The first time I wrote a financial report, I mostly copied an existing template. Over time I got accustomed to the terminology/phrasing/register of that sort of content. Mouthwork You can think of this as being both the “applied pronunciation” section or as being the “conversation preparation” section. For now, this is a purely physical practice that we’re doing for the purpose of getting to know your mouth and how to manipulate it. We just happen to be using Japanese words. Page 102 If that seems odd, click through this 3 minute progress video of a guy learning to dance. At first he’s shuffling around uncomfortably in his living room, but things change as the video goes on. He learns how to control different parts of his body, what it feels like to move in and out of certain positions, how to balance in a variety of positions, he gets stronger, he eventually remembers that we can still see his shoulders even if he’s doing something that primarily involves his legs. Soon he’s dancing. A similar progression is going to happen inside your mouth. It’s unfortunately quite difficult to see what’s happening in your speech organ and mouth, so you’ll have to rely on how things feel and how they sound. At first you’re going to be forcing the square pegs of English mouth shapes onto the round shapes that are (intended) Japanese sounds; it’ll be a chaotic and blurry menagerie of sound. Before long you’ll start to figure out which physical movements yield which sounds, giving you a bit of control. You’ll grow accustomed to which sounds tend to get strung together in Japanese and it’ll start to feel more smooth. You’ll begin respecting the consistent division of each mora/syllable and differentiating long vs short vowels and things will begin to feel more uniform. Like the dancing guy. Anyhow, let’s learn to dance. Mouthwork: A process of exploring your mouth and speech organ This will take one minute per day, so turn it into a trigger-action plan. Associate it with the same event every day; maybe when you get in the shower or are trying to convince yourself to get out of bed in the morning. It doesn’t matter when, so long as it’s easy to be consistent with. I’ll give you a few prompts to start with, but before long you’ll be making your own. It can be any movement between two sounds or any variation you could think about adding to a sound. Only do one per day; this should be easy enough that you stick with it, and spacing the actions out lets you take advantage of the serial position effect. 1. Vowels a. Say ahhh, as if the doctor has just asked you to do so. Take a moment to notice where your tongue is, the shape of your lips, whatever comes to mind. b. Say ohhh, and take a moment to orient yourself again. c. Very slowly, go back and forth between the two sounds a few times. Pay attention to the movement of your tongue. Pause at the end of each movement. d. In a manner that makes sense to you, make a mental note about where your tongue is for ohhh versus ahhh. e. Do this for all the vowels. Start with ones you know, in order to orient yourself, and then start making stuff up. What does it sound like if you put your tongue in the spot halfway between ohhh and ahhh, for example? f. As time goes on, you’ll build a sort of mental map of your mouth that provides you with a general idea about what sounds come from where. Page 103 2. Consonants a. Say “buh”, the sound someone makes when they’re stuttering and say b-b-b-b-b-but! b. Say thhhh, the sound at the beginning of the. c. Again, take a moment to appreciate what happens with each sound. Which part(s) of your mouth are involved in the sound? What parts of your mouth does your tongue touch? Does the airflow get interrupted, or is it continuous? d. Once you’ve decided what’s happening with buh and thh, swap them. Keep your mouth in the same position as it was for thh, but make a movement like the one you do when you say buh (the build up and exploding feeling). What happens? e. Pick random pairs of consonants and continue on. f. As time goes on, you’ll build a repository of tons of cool information. Which part of your tongue touches which part of your mouth to make each consonant, how changing the flow of air affects the sound, that sort of thing. 3. Voicing: what your vocal chords are and what causes them to activate a. Take your thumb and forefinger and place them on either side of your adam’s apple b. Pick a random word. If you’re indecisive, go with dream. c. Say it out loud, in your normal voice. Pay attention to your adam’s apple. d. Say it in a whisper. It should feel very different. It’s impossible to miss. e. Say it aloud again. Notice where you feel stuff happening. f. Say it in a whisper again. Notice where stuff suddenly isn’t happening. g. Pick random sounds in random words and pay attention to your adam’s apple. If it's vibrating, what do you need to do to stop that vibrating? If it isn’t vibrating, what do you need to cause it? 4. Aspiration: how much breath is released with a consonant a. Hold a hand in front of your mouth, as if you were sniffing your fingers b. In a normal voice, say the word kite. A few times fast, a few times slow, you do you. Pay attention to what happens around the k sound. In particular, pay attention to how much air is exhaled into your fingers. c. In a normal voice, say the word sky. Again, pay attention to the k sound and how much air hits your fingers. d. Focus on the k sound now. Say k as it is in kite, follow up with the k as it is in sky. How do they feel different? What is happening in your throat? e. Take the word kite. Try to learn to control how much air is released on that k - what do you need to do in order to cause more or less air to come out? f. Experiment with other words and consonants. That should get you started; random ideas should come to you as you skm the pronunciation section. If not, check out this playlist of short videos. Remember, one idea at a time. Page 104 You’ll sometimes end up stumped. Take the sounds that confuse you and make mouthwork sessions out of them. It’s okay if you don’t find the answer, just explore and see what you learn along the way. Anki: a convenient place to apply the stuff you learn about pronunciation As you learn your way around your mouth, start applying this to anki. How do you get from an English u sound to the Japanese u sound? Etc. Don’t take it too seriously, just play around. Certain sounds will stick out to you; try to replicate them, and see what you learn along the way. 1. Periodically work through content in the pronunciation chapter. a. You might do it intensively, in which you go down the rabbit hole and try to make sense of all these fancy English words that seem too complicated for their own good b. You might do it extensively, in which you skim through a resource, pick out a single new idea that sounds interesting, and just stew on it for awhile before moving on. c. Both are useful and do different things. Follow your mood. 2. Apply this stuff when you’re doing Anki. a. Say you just learned that English speakers tend to dipthongize their vowels, so you decide to focus on not letting a little u sound slip into the end of the vowel when you say something that starts with an o sound. b. It’s okay if you get literally everything else wrong. We’ll be sticking at this for awhile, so for the time being, just worry about your one thing, whatever it is. Every time a relevant sound comes up in Anki, give it a bit of extra attention and figure it out. c. Over time, you’ll gradually incorporate more of your pronunciation knowledge into your active speech. As you get to know your mouth better, it’ll get easier. Scripting In the start here section of the pronunciation, I included the following in a bullet point: Page 105 Understanding something, nailing it in practice and using it spontaneously are different things. Here are reasons teachers fail to teach pronunciation, with solutions. ( I and II ). I think the “reasons” video is really important, as you’re probably going to be your own teacher, so I’m going to summarize Hadar’s “5 P’s” of pronunciation here. The video goes into more detail. - - Perception: Before you can learn to make a sound, you must learn to recognize it. Pronunciation: Exactly what must physically happen inside your mouth to make a sound. Most students will first need to learn how their speech organ works and what it feels like to manipulate it. You may round your lips even if you know you shouldn’t because you haven’t had the opportunity to differentiate what rounded vs unrounded lips feels like (mouthwork!). Predict: Knowing what your student is likely to do, based on their native language, you can provide them with pre-emptive pointers about what to focus on. Performance: Observe the performance of your students; give precise, concrete feedback. For example, your lips are rounded; relax them when you make this sound in Japanese. Practice: Practice makes better. Partly because of muscle memory, partly because the more you practice, the more you’ll understand what your mouth is doing, giving you information about what gradual adjustments you can make to work towards the correct sound. As you can see, there is more to this than simply learning about pronunciation. 1. In the pronunciation chapter we compared the sounds in English and Japanese, learned how they differ and did some minimal pair training to learn to perceive Japanese’s sounds. 2. In the phonetics section we learned how linguists describe what happens with our speech organs when we speak; in mouthwork we grounded that knowledge in experience. 3. Many articles I linked gave pointers about common mistakes that English speakers make, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you know how to avoid making those mistakes. In this section we’re going to work on the final two P’s. - You’ll be recording yourself. Compare your performance to the original one, listen for where they don’t line up. Try to use your pronunciation knowledge to make guesses as to why. Presumably you already know what you need to do, and in the section on mouthwork you hopefully figured out how to make many of these sounds in isolation. Now we’re going to work on making it more automatic, for you to get so comfortable with the rhythm and feel of Japanese that you make many of the right choices on the fly without thinking much. The Control Variable: a measuring stick to glance at from time to time 1. Pick a single brief recording of something in Japanese. It can be anything. Your favorite line from an anime, a verse from a song, some vlogger ordering coffee, whatever floats your boat. 2. Record yourself repeating this phrase. It’ll probably suck. That’s okay. It’s why we’re here. Page 106 3. 4. 5. 6. Listen to yourself and then that person. Pick out a spot or two where they differ. Forget about it for a few days or a week. I’m not picky. Repeat steps 2, 3 and 4 indefinitely. Not forever, but give it a while. As a note, this shouldn’t take long. Listen to the native recording, record yourself, compare, go on with your life. It’ll take a bit of effort to memorize at first, but after that, this should just be a few minutes of your life once or twice a week when you’ve got nothing better to do. Now, I assume that you’re putting in your one minute of mouthwork each day, so each time you re-do this recording, you’ll have accrued a little bit more knowledge about how your mouth works. Apply that knowledge; each time you record, you’ll make a few sounds a bit better. The Prepared Conversation: rehearsing your half of the conversation beforehand Assume you’re about to meet someone for the first time; what sort of things are going to come up? You can probably name several things, and that means we can do a bit of preparation beforehand. You’ll get better at improvising and chatting on the fly as you go, but for now, preparing the main chunks of a simple conversation will help to smooth the first few conversations along. This comes from The Mimic Method, a website that aims to help people learn languages “by ear.” 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Write out your self-introduction in English Have it translated (language exchange partner, iTalki tutor) Ask the translator to also record themselves reading your script in a natural voice Practice along with the recording until you can do it in real time Once you’ve got it memorized, focus on prosody and tricky sounds This seems fake and artificial, and it is. I don’t personally think that makes it useless, though. - You’ll have to give this spiel all the time, perhaps each conversation. It’s full of simple grammar points and words that are important to you You’ll pick up lots of useful conversational connectors you can recycle elsewhere It’ll get you over a major hurdle: dealing with the unrealistic and inaccurate delusions your anxiety feeds you about how scary or embarrassing it is to converse in Japanese Forcing yourself to pay so much attention to a piece of Japanese speech will let you notice stuff you might otherwise have missed. Hopefully they'll roll over into your normal speech. Speaking, in any capacity, involves stringing a lot of Japanese sounds together. You don’t need to be speaking spontaneously to train your mouth to make the right movements. Early Conversations I’ve written separate posts on getting the most out of an iTalki lesson and what I think the needs of different-leveled students are, as a tutor. To be blunt, though, there just isn’t a whole lot of art to Page 107 these first conversations. Every single one will be full of “I want to express [idea], but I don’t know how.” So you ask your tutor, they tell you, and ten seconds later you find yourself stuck again. There are, however, a few notable pieces of good news: 1. 2. 3. 4. No matter what you do or don’t do, you can’t help but learn something each lesson You’ll likely see tangible, notable improvement from lesson to lesson You don’t need an expensive, experienced tutor; just a patient person You’re in for a series of massive, frequent dopamine spikes For the moment, you’re blind, on crutches and there are holes (ideas you don’t know how to express) everywhere. It’s not practical to fill them all in right now, so just do your best to remember where they are. Furthermore, since we’re not concerned with filling them in, you don’t need a super strong partner; just somebody patient who is willing to help you out when you stumble. As you go on, you’ll get more familiar with the layout of the land: - You’ll have laid a board across certain holes, enabling you to tightrope-walk over them Some holes are too big to traverse, so you’ll have learned to maneuver around them Some holes are small enough that they’re easier to fill in than constantly trip over You have three responsibilities: - For now, just get through the conversation—this is how you learn to navigate the field Bring something new into every lesson; this is the board you’re going to cover a hole with Be patient; you need to get off the crutches before we can learn to run and dance and stuff Incorrect, unnatural, banal and inert As far as I can tell, there seem to be two main reasons that people shy away from output: - It can be a nerve-wracking and stressful experience They’re worried about making, or internalizing, mistakes I hope that the sections on mouthwork and scripting will help those who struggle with nerves, but I’d like to make an appeal to those who feel a need to wait just a little bit longer, to get just a bit better, before they begin speaking Japanese. I’m not going to challenge you or anything, I’d just like to share how I personally look at the learning process. A lot of learners seem to put grinding on a pedestal: if I learn 3,000 kanji, I can read! If I learn these 200 jlpt grammar points, I’ll be fluent! If I learn these 2,000 key words, I can have conversations! Page 108 The problem is that gaining proficiency isn’t such a linear process. The gap between learning and producing generally correct and coherent language is big, but the gap between coherent language and admirable, excellent language is incomparably bigger. Even then, there is a gap still between beautiful and moving. The journey doesn’t end at fluency; on the contrary, that’s where it begins. For example, I’m a native English speaker who writes for a living—mostly news releases and press articles. Despite the fact that I’m a native speaker, though, everything I write gets revised by at least two people. The fact that my writing is intelligible, mostly natural and has few if any outright errors doesn’t mean that it is engaging, concise or effectively doing the job it was supposed to do. The fact that my writing is coherent doesn’t make it something people want to read, let alone memorable. Here is draft 1 and draft 2 to the first chapter of a novel I’d like to write. If you skim through the highlights and comments, practically none of the comments I got are talking about grammar. I’m getting feedback about voice, framing, how characters interact, etc. This is correct and native English, but it’s also bad writing. There is more to telling a story than language mastery. Needless to say, there is a macroscian gap between myself and successful authors like Stephne King or JK Rowling. Furthermore, the fact that they’re successful doesn’t necessarily mean they’re good writers. Don’t get me wrong: I, obviously, can not write like they do. But what carries these authors is not their prose in and of itself. JK Rowling is a master worldbuilder and Stephen King has an uncanny grasp on the human psyche that lets him build characters we can sympathize with. Just as there is a huge gap between myself and these authors, I feel it is fair to say that there is a similarly notable gap between their prose (the physical writing they produce) and the likes of someone like F. Scott Fitzgerald, someone renowned for the lyricism with which he writes. Just skim the most quoted lines from the Harry Potter series, The Great Gatsby, and a story that I wrote. - Practically every single sentence in Gatsby is a moving line of poetry Most lines from Harry Potter do the job, but they aren’t particularly notable Nevermind the story itself, many of my own sentences fall short of being even passable Writing is my damn job, but I still stumble all over the page. I think that’s a point worth noting. Correct doesn’t mean natural, natural doesn’t mean elegant, elegant doesn’t mean deep. My point is that I think it’s a waste of time to fret about crossing all your T’s and dotting all your I’s because what matters is what you can do with those letters: You don’t succeed with language alone. JK Rowling has enraptured the world with her fantasy, despite the fact that her writing could be There is certainly a minimum proficiency-floor necessary to communicate, but past a certain point, your ability to connect with people seems to be more important than your mastery of the language. I don’t think it’s possible to get that ability from a textbook or proficiency test. Page 109 Conversations This section and the last one have quite similar titles. I’ll change them if something better comes to mind, but I’m more concerned with the problems you’re dealing with in each section, rather than any temporal notion of how long “early” lasts. Previously, we dealt with linguistic problems and emotional problems. - Maybe you were self-conscious about your accent Maybe you were afraid the tutor wouldn’t understand your “terrible” Japanese Maybe you were afraid you couldn’t keep up with your tutor’s Japanese Maybe you were worried about not having the words/grammar to express yourself Maybe you felt nervous about the thought of communicating in not-English (Anything that doesn’t explicitly concern Japanese as a language goes here) Like many unwarranted assumptions, these sort of self-damaging thoughts often won’t stand the test of reality. An important outcome of our first few conversations is simply having the opportunity to wade through whatever unfounded assumptions you’ve come to harbor about Japanese and your ability to use it. In the last section I commented that you’d likely see notable improvement from conversation to conversation, and this is why. That’s not because your Japanese is rapidly improving, but rather because you’ve dropped a lot of baggage that had been weighing you down. In addition to these more emotional issues, you probably solved a few practical problems, too: - You mastered a few go-to conversational connectors to help string your thoughts together, buy you more time to think, direct the conversation, and so forth You’ve mastered a few power phrases like what does ___ mean? Or please say that again. You’ve gotten better at using circumlocutions to talk around words you don’t know Through trial and error, you’ve gotten a much more tangible idea of which grammar points in your disposal will and won’t help you express the thoughts you frequently express You’ve gotten much quicker at any sort of conjugation Generally speaking, you worry less and less about getting through the conversation. You develop a sort of confidence that you will understand and also be understood. Eventually, your “first few” conversations will come to an end and you’ll move onto the “conversation” stage. Exactly how many conversations the “early” stage consists of will differ from person to person, but you’re there when speaking Japanese becomes a mundane thing. If you want a litmus test, a good indicator you’ve reached this point is when, at the end of your tutoring session, you go wait a minute, I got literally nothing out of that. It was a waste of money. Page 110 Now that we’re reliably and comfortably getting through conversations, we can start turning a critical eye to the process in order to ensure that we are actually benefiting from them. Outcomes over Output In a sentence: what did you actually get out of that conversation? How is your Japanese better for it? In 2010, Public Relations professionals met in Barcelona, Spain to discuss a set of guidelines for measuring the effectiveness of PR efforts. The result was the Barcelona Principles, the second of which encourages PR agencies to care more about outcomes than output. In other words, more important than how many press releases or ads that get put out is what they accomplish. As your ability to speak improves, I’d like you to start thinking about outcomes, too. Eventually, and most likely sooner than you think, you’ll reach a point where small talk just doesn’t help you—you can do it in your sleep, don’t struggle and don’t really benefit from it. Next it’ll be introducing yourself, the routine things that come up in your day, your interests, etc. Once you’ve learned the ropes and have the motions down to a T, going through the motions ceases to help you. Here are a few things I do to get the most out of my exchanges and iTalki sessions: Preparation Asking good questions is hard, and it quickly gets more difficult as you improve and most information moves from “I have no idea what this means,” to “it’s kinda fuzzy.” That in mind, unless you’re a very early beginner or don’t mind throwing lots of money at this, you should be spending significantly more time preparing for a tutoring session than you actually spend in it. - - - If you’re a beginner, I think you should be working through textbook content together. I think using grammar ourselves helps to master it, but more important than that, this artificially limits the scope of your conversation, greatly lowering the skill floor. If you’re an intermediate learner, which I’m defining as being able to work through content you enjoy, you’re probably stumbling into all sorts of confusing stuff on your own. Keep track of these questions so you can talk about them with your tutor, and if you’d like a challenge, try to explain the plot/what the story was about/etc to your tutor. If you’re an advanced learner, you’ve covered a lot of ground and can talk about a lot of things. You might, however, struggle to explain things precisely or concisely. The most useful exercise I’ve found is to pick random topics and give yourself a time limit, or research a specific topic beforehand and explain your stance on it within a specific time limit. If you go over time, ask your tutor to help you explain those thoughts more efficiently. Priming Whether you’re consuming content or working through a textbook, you’re surely stumbling into stuff that you think would be nice to remember. I personally find that making a point to use Page 111 grammar/vocab in a conversation helps me to remember them, so throughout the week I flesh out a list of questions I want to ask/stuff I want to work into my next conversation. I personally use the Sat/Sun section of my planner for this, and I just skim through it before a lesson begins. Flagging If priming is a list generated from input, then flagging is a list generated from output. No matter how proficient you are, you’ll struggle to express certain things: keep track of these things. So long as you’re being mindful, output is an excellent means to give your input direction. The idea is that you encounter ideas you struggle to express via output, then keep an eye out for vocabulary and grammatical structures that you could have used to express them while immersing. Having this sort of direction helps to make useful structures stick out. - - - If you’re new to conversing in Japanese, you’ll inevitably stumble into a disconcerting amount of ideas that you don’t even begin knowing how to express. In my early conversations, I probably spent more time sitting tongue-tied than talking. If you’re relatively comfortable chatting, you’ll still find many ideas that you’re capable of expressing, but not quite as concisely or naturally as you’d like—or maybe it’s a sensitive topic and you can’t quite convey the nuance you want. Even after you’re completely comfortable with Japanese itself, you’ll find you struggle with domain-specific knowledge within Japanese. The problem isn’t Japanese, but the specific (and arbitrary) language that has been accepted as standard for delivering a eulogy or discussing financial forecasts or whatever it is in Japanese. Just because your Japanese is grammatically correct or natural in a colloquial sense doesn’t mean it sounds professional or educated. Even native speakers must spend time figuring this out. Closing Words Just to be clear, this isn’t about input or output, but input and output. Just as there are (likely) many kanji you can recognize on sight but not write out from memory, the fact that you’re capable of comprehending an idea expressed in Japanese doesn’t mean you’re capable of expressing it yourself. In my experience, it can be difficult to pick out things you can and can’t express until you’re put in a situation where you have to do so. This in mind, I believe that output is an excellent means to give your input a bit more direction and structure. Upon discovering that you can’t quite express an idea as well as you’d like, you can then approach your input with a bit more purpose. The result is that, by the time you find yourself in another situation where you have to express that idea again, you’ll have had the time to pick up a few tools to do the job that you might have overlooked otherwise. Page 112 Interviews Before we get into the conversations, I’d like to briefly explain how I went into these interviews and then quote a paragraph from a book on writing to elaborate on why I wanted to do it like this. Simply put, I had two goals going into every one of these conversations: ● ● Be able to present something concrete and useful to learners; replicable approaches and tangible insights that might not otherwise be apparent to a beginner. In some small way, give each creator a platform in which they can share with learners a bit of the sense of wonder they find in their areas of specialization. That in mind, I’ve intentionally strayed away from pointed and/or negative questions. My goal here is to gather insights that can help you, and I believe that each creator here has something to offer. As Ronald D. Tobias says in 20 Master Plots: And How to Build Them: If you use your characters to say what you want them to say, you’re writing propaganda. If your characters say what they want to say, you’re writing fiction. I’m not interested in serving language learning propaganda to you. There’s plenty of that out there. How, then, do you avoid writing propaganda? First start with your attitude. If you have a score to settle or a point to make, or if you’re intent on making the world see things your way, go write an essay. If you’re interested in telling a story, a story that grabs us and fascinates us, a story that captures the paradoxes of living in this upside-down world, write fiction… You can always tell propaganda because the writer has a cause. The writer is on a soapbox lecturing, telling us who is good and who is bad and what is right and what is wrong. Lord knows we get lectured to enough in the real world; we don’t read or go to the movies so someone else can lecture to us some more. Isaac Bashevis Singer claimed characters had their own lives and their own logic, and that the writer had to act accordingly. You manipulate characters in the sense that you make them conform to the basic requirements of your plot. You don’t let them run roughshod over you. In a sense, you build a corral for your characters to run around in. The fence keeps them Page 113 confined to the limitations of the plot. But where they run inside the corral is a function of each character’s freedom to be what or who he wants within the confines of the plot itself. - Tobias, Ronald B.. 20 Master Plots (p. 51-52). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. The plot we’re dealing with here is your own learning, and the “corral” I’ve placed each creator in is that they must work towards benefitting your learning; helping you to do what they specialize in. Idahosa Ness on Pronunciation Idahosa believes that phonetics is the foundation upon which language learning rests; he encourages people to learn languages by ear, tuning into its array of elemental sounds. I find Idahosa to be very personable and good at approaching the stuff he discusses in a manner that’s relevant to his audience. I think that the study of pronunciation gets a bad rap amongst language learners, so I approached him in the hopes of making it more tangible and real: ● ● ● ● Why people should care about pronunciation in the first place, anyway What the process of going from zero to speaking a foreign language looks like, to him What is a simple way that people can practice their pronunciation for free What are the most common pronunciation mistakes an English speaker will make? What is listening, actually? Something that I think a lot of people miss is that audio input is actually a combination of two things: objective sounds that can be measured, yeah, but also our subjective perception of those sounds. I can perfectly understand and replicate English sounds because of the mirror neuron effect: as a kid I heard the people around me making certain sounds with their mouths, I mirrored those sounds and after a few years I became able to perfectly mimic my peers. This basic set of sounds formed the foundation upon which everything else I ever did in English rested upon. You might say that we’re “in tune” with English. We’ve got the tuning knob set to 100.8 or wherever it is and all the waves are coming in nice and clear, which then enables us to correctly make out what people on the radio are saying. When we can make out what they’re saying we can then process it, engage with it, and respond to it. Being in-tune with English is essential for us to function in an English speaking society. That being said, it also creates some problems for people that later on try to learn a different language. Each language has its own “radio station” of objective sounds, so to speak. When we hear a foreign language for the first time it’s just static on the radio. Working on pronunciation is just a process of messing with the tuning dial to find clearer channels, gradually reducing the static until we’ve found the right station. Once you’ve got that, it’s not a problem to bounce between 96.4 French and 100.8 English, or whatever your languages are. Page 114 An Exercise: How can complete beginners begin thinking about pronunciation? There are lots of fancy tools like the international phonetic alphabet that help us describe sounds more accurately, but all of that stuff is ultimately just a means to an end. The end goal is just to be able to move your mouth in a way that accurately mirrors a Japanese person’s mouth. The first step to that goal is simply noticing when discrepancies exist between the sounds coming out of your mouth and a Japanese person’s mouth when you’re talking. So here’s what we do: Here’s how you can start learning the phonemes that exist in Japanese: 1. Get ahold of some brief recordings of Japanese speech; a few seconds at max. (Sui: you might take the MP3s from the Core2k on Anki, look up random words on Forvo or take audio clips from Japanese YouTube vloggers) 2. Record yourself trying to mimic whatever you just listened to 3. Download a free program like Audacity that lets you slow the tracks down, layer them on top of eachother and listen to both at once (tutorial). 4. Listen for discrepancies. For now we aren’t worried about why these discrepancies exist and we’re also not worried about how to fix them. Write out what you were saying, listen along and then just mark whenever something sounds funny to you. (Sui: If you’ve ever played music, Idahosa is basically talking about consonance and dissonance. Where do your sounds match natural Japanese, where don’t they?) If you can, it’d be great to grab a Japanese person to help you with this. Again, they don’t have to know why you sound funny; we’re not worried about the why for now. Just have them listen along and mark your speech up—you sound like a gaijin here, here and here. 5. As you go on, try to observe patterns of discrepancy that exist between your speech and Japanese people’s speech and make a short list of them. You’re going to get a lot of them right, because Japanese and English phonemes have a good amount Page 115 of overlap, but you’ll also notice some stuff that doesn’t quite feel right. 6. Once you’ve got your list, start paying attention for those discrepancies. Be active about it; mimic what you hear, and don’t just do the same thing. Change the shape of your lips, move your tongue around a bit. Experiment and look for stuff that lessens the discrepancy between your speech and a Japanese person’s speech. General Pronunciation Training A bit of knowledge becomes helpful at this level. You could approach all this stuff in so much more depth, so you don’t have to step here, but to put it very simply: ● ● Consonants and vowels are articulated in specific ways. (Sui: those “specific ways” he’s referring to are place of Articulation, manner of Articulation, and voicing. You can also describe vowels in terms of height, backness and rounding.) Syllables are arranged melodically: (Sui: see below sections two and three). Depending on how much you know about pronunciation, spending a bit of time learning about how this stuff works might be beneficial. Anyhow, at this stage, you’ve got a couple main goals: 1. Learn to correctly say all of the syllable combinations that exist in Japanese (Sui: the “combination of sounds” is referred to as “phonotactics”... super cool! In Japanese, this basically amounts to learning the kana. Idahosa is technically referring to what’s referred to as morae and contonation… a mora is basically a kana, but not always. Sometimes putting two kana together will yield one mora, as with きょ - kyo.) This involves a lot of just playing around, too. Just talking about vowels—whether your tongue is up or down, forward or back, whether your lips are rounded… all this stuff affects the sound that comes out of your mouth. Move your tongue around and see what effect it has on your sound. What’s the difference between a vowel that’s more forward and one that’s more back? What happens when you make a small, tight circle with your lips? 2. Isolate its intonation patterns; for now, just practice by humming along with speech. (Sui: this means learning the basic pitch accent patterns; what patterns are, and are not, possible in Japanese? && there’s an activity/example on page 3 of the first link). 3. Pay attention to the rhythm of Japanese speech: make some nonsense sounds to the beat. Shall I com- pare thee to a sum- mer day? ti TA ti- TA ti TA ti TA ti TA Does rhythm work the same in English and Japanese? English has stressed syllables and unstressed syllables; does Japanese? English dices up sounds and makes liaisons; does Page 116 Japanese? Japanese speech is pretty fast, so you’re probably not going to be able to mimic at full speed right away. Take some time to learn about how sound is made and, armed with that knowledge, start mimicking it. You’ll gradually “tune in” to Japanese the more you actively listen. As you begin hearing more clearly and noticing more patterns, try to replicate them in your own speech. Building Lines and Stacks You need vocabulary words to speak a language, but it’s important to remember that words are not isolated little specks of language. What’s more important is the lines and the stacks that these vocabulary words are parts of. (Sui: he’s talking about the paradigm and syntagm here). I don’t think that there’s a really good tool focusing on this specific stage of language acquisition, so I’m currently in the process of putting together an application called Stax. The app is designed to help you learn to freestyle rap and is based around organizing stacks (actors, actions, objects and settings) in different ways to create unique lines, which you then put to a beat. You’re basically getting practice making sentences that focus on these elements. For example, I don’t speak Japanese, but I have picked up a few random words from the interactions I’ve had with Japanese media. I know a word for I, ware, a word for rice, gohan, and a word for eat, taberu. Now I’ve got a basic line: ware, gohan (wo) taberu! This line is made of three different “stacks” -- actors, action and object - and as I learn more words, I can swap different ones in and out with other words that are in that stack’s “word cloud”— all the words the relevant words I’ve been exposed to that are within my grasp of Japanese. That cloud will gradually grow as I encounter more words that I’ve got a real-world need for. It isn’t the mere presence of these words that matter, it’s the connection between them that matters. I’m not using the words ware… gohan… taberu… I’m using the line that I’ve drawn between those words. Language learning is a process of accumulating more and more lines that bend in ever more abstract ways. After all, we don’t just want to memorize words; we want to integrate them into our lives. We do that by having meaningful experiences with these words, and creation is one type of meaningful experience. The more you mimic and create, the more resourceful you become. It isn’t enough to just know the word for rice, you’ve got to be confident and resourceful enough to use it at the drop of a hat in a real conversation. You’re building that confidence and resourcefulness during this stage of pronunciation practice—both putting in the mouth work you need to be comfortable making Japanese sounds and the mental work you need to be comfortable building Japanese lines. Page 117 This is a skill that needs to be practiced, even in our native languages. Scripting A script is, fundamentally, a prepared conversation. During this stage you’ll be identifying and practicing scripts. You might: ● ● Take a clip of a native speaker speaking Write a self-introduction or a paragraph in your native language, send it to a native speaker to have it translated into your target language. Ask them to record themself reading it in a natural fashion and send it back to you. Once you’ve got your script, approach it in the same way you did the activity from earlier. 1. If you’re here, you should understand Japanese at a syllabic level. You know the sounds that exists in Japanese and you can make them mostly accurately. 2. Practice stringing all of the syllables together to make the words of your script, the words to make phrases, the phrases to make sentences, and the sentences to make your paragraph. Each new level builds on the previous one. 3. Keep practicing until you can match native speed. You’ll need to put in some significant mouth-work to feel comfortable doing this. 4. After you’ve got the words down, spend effort to also match the rhythm and intonation of the native speaker. 5. Keep tweaking stuff until your recording sounds as close as possible to the original. Now bring that script into a conversation. ● ● ● Focusing on making use of the words in your script and further committing them to memory Look for opportunities to build your “stacks” and expand your “word cloud” As you accumulate “lines”, play around with them. You can recycle lines and stacks to express a lot of new and novel ideas. Eventually you’ll accumulate enough words and lines to communicate, and with that comes the confidence necessary for spontaneous conversation. From this point on, you should always be on the lookout for new lines. Page 118 Idahosa walked one of his team members through this process, which you can watch on YouTube (the bit about scripts is Episode 4). Reflecting on the experience in Episode 9, Mike comments: It was really helpful to go back and review the things I was saying on my calls with a tutor or whoever I was talking to. It helped because I could see exactly what I was doing and the bad habits I had in the middle of a conversation—stuff I didn’t necessarily notice in the moment. After viewing that I could go back and figure out how to say something better or more naturally. Closing Thoughts The 80/20 of pronunciation mistakes that native English speakers will make in Japanese ● ● ● Pay attention to the length of your [mora]. They vary in English, they don’t in Japanese. Pay attention to your tongue and lips; the positions of EN/JP vowels aren’t quite the same. Unlike in EN, there isn’t movement within JP vowels (Sui: Idahosa is talking about diphthongs, which he talks about in this post on accent reduction. Articulate each vowel!). And a few closing thoughts to leave you with: ● Learning is complex. Be it language or any new skill, it’s super complex at first. At first you’ve got to use the logical/analytical part of your brain to put all the pieces together manually at first, but with good practice and repetition, all that eventually gets pushed into the back of your brain, your intuition, and becomes automated. We started by talking about hearing phonemes. At this point you might not even know what a phoneme is and it takes a lot of conscious effort to sort all the sounds out, but over time, it becomes automated. Once that’s automatic your brain space will be freed up to focus on other stuff: rhythm, intonation, etc. Once that’s all automatic you don’t have to worry about how you’re saying something and can focus purely on what you’re saying: building vocabulary, using more complex grammar, etc. It all builds on itself. ● Believe that it’s possible—understand that pronunciation is movement. To fix your pronunciation is to change your movement patterns. Know that as a human being, you have the capacity to change the movement patterns of your mouth, just as you can do so for running form or any athletic form. If you believe, pay attention, put in the smart effort… You are capable of changing your habits. ● Don’t just rely on your ears—stare at peoples’ mouths and try to mimic the way their mouth is moving. The act of bringing your conscious attention to that space will make a huge difference. Page 119 ● Turn on a variety TV show or something where you can actually see peoples’ mouths moving and put it on mute. Try to match their mouth movements, head gestures, etc. Facial expressions, physical gestures, and how you carry yourself are all parts of communicating in another language, too. Matt vs Japan on Pitch Accent, Kanji and The Journey Matt has a very advanced level of Japanese and leverages his experience to create content that helps learners get started and deal with hurdles they encounter. Founder of Refold.la, he encourages learners to spend as much time in their target language as possible and believes that output abilities are eventually acquired as a natural result of comprehending large amounts. Immersion, he says, is the most important part of the process. I was excited about how willing Matt was to elaborate on his thinking and found that he is very good at coming up with metaphors to make the complex ideas he’s presenting more tangible. We ended up covering much more content than I expected, but our discussion centered around: ● ● ● ● Pitch Accent—what it is and how to approach it Kanji—insights he’s obtained by observing the progress of over 100 learners Anki—what it’s for and how you use it will change over time The “Journey”—some thoughts on planning your own learning On Learning Pitch Accent Note: If you haven’t worked through the earlier section on prosody yet, or you’re just here for the interview and aren’t following the document, please spend 20 minutes getting an overview of pitch accent before continuing. This will be easier to follow if you’ve got a loose idea of what’s going on. - Japanese Pitch-Accent in 10 minutes (II) The Challenge and Intrigue of Pitch Accent (~2.5k words) Before we get started, do you have any general comments to make about pitch accent? I’d like to begin by saying a few things: - - I like to separate pitch accent from pronunciation. I know people who have excellent pronunciation but make many mistakes with pitch accent, and I also know people who have pitch accent down but get a lot of the sounds of Japanese wrong. People can reach a very high level of Japanese without picking up on pitch accent, especially if there isn’t a similar feature in their native language. It takes intentional effort to figure out. Page 120 - Even if you completely ignore pitch accent, it doesn’t really become an impediment to communication. You can almost always rely on context to make sense of what you hear. This doesn’t mean pitch accent isn’t important. The fact that you’re able to be understood doesn’t mean that your Japanese sounds good to a native speaker. (English examples). Perhaps most importantly: I think there’s a lot of people who brush off pitch-accent because they can’t perceive it and don’t realize how significant it is. What would you tell someone on the fence about the value of pitch accent? Even if you completely ignore pitch-accent, you’ll still be understood. Sometimes messing up pitch-accent does interfere with communication, but most of the time a pitch-accent mistake will just cause you to sound foreign—as if you were constantly stressing the wrong syllables in English. In my case, I’m a perfectionist. Pitch-accent is important to me. Having said that, if you really don’t care about how you sound… I can see that maybe studying pitch accent isn’t worth your time. That being said, I think if you just learn the very basics of pitch accent (the rules, the difference between pitch accent and intonation, the general rules to how it works), enough to become aware that there are these 4 patterns and they roughly sound like this… that enables you to listen for it. Knowing the basics is the difference between having and not having a framework. It’s much harder to learn if you don’t have a general idea of what you’re looking for. If you don’t get this framework, you might find that you genuinely can’t hear the difference between correct and incorrect accents. While it will take a long time to master pitch-accent, you can learn those basics in 30 minutes. If someone is struggling to hear the differences between each pattern, what should they do? I actually just recently worked with someone who was having exactly this issue, and in his case, it was a straightforward fix that anybody can do on their own at home. 1. 2. 3. 4. Learn about the four basic patterns (ie, go through those links above) Take a piece of paper Split it into 4 different quadrants Assign each pattern to a different quadrant (ie, top left=heiban, top right=atamadaka, bottom left=nakadaka, bottom right=odaka). 5. Figure out how to use a Japanese-Japanese dictionary and find a word’s pitch accent (in incredible depth, in ~3 minutes, via the MIA Dictionary App) 6. Look up common words you know until you find 10 words for each pattern 7. Place those words into their respective quadrants on your piece of paper Page 121 8. For now, don’t even worry about how pitch-accent works for verb/adj conjugations or any rules like for compound nouns. That’s too much to learn all at once, but if you build a good foundation, it will start to come together over time. 9. When you’re immersing and you hear one of your 40 words come up, rewind a few seconds, listen again, and really focus on the pitch pattern. What does the pattern feel like to you? 10. It’s natural if you can’t hear pitch at first; it’s a skill you need to develop. You need to give your brain a system of feedback: if you’re playing marco polo, but the other person never says polo, you could progress super far… in the wrong direction. Unwittingly. This is a process of hearing an odaka word, like hana, and being like hey, that’s odaka! And eventually, after hearing a lot of odaka words in many contexts, it eventually sinks in. Before that point, though, you’ve got to get through the difficult process of reconciling [what you think pitch-accent is, based on your interpretations of someone else’s explanation] and [what pitch-accent actually is]. 11. Once you get better at Japanese, try to read the back of the NHK accent dictionary or the shinemikai accent dictionary. There’s a solid explanation… it’s just in Japanese. So, to put that in really general terms: - First just learn what the patterns are - Next, learn to hear each pattern - Next, learn the patterns of common vocabulary words - Eventually you’ll start picking up on rules/exceptions and how conjugations work - Way down the road you’ll get into really particular rules This progression should play out alongside the rest of your studies. There’s no reason to think that you’ve got to learn all this right now. ● ● For beginner/intermediate learners, it’s enough to just know the patterns of isolated words and be able to listen for them. Once you get more advanced, and you’ve got more of a foundation in Japanese, you can start worrying more about conjugations and stuff. It’ll be easier to get your head around then because you’ll (a) have developed a more accurate sense of intuition about how Japanese sounds and (b) be able to use Japanese resources, which have more detail than English ones. That’s a lot of memorization… can we Anki our way through pitch-accent? I think that it’s really important to hear a lot of natural Japanese. There’s only so much detail you can fit into a single anki card, and there’s a lot of subtle stuff that you might not perceive (and thus not be able to put on an anki card in the first place). That aside, anki is a great tool for memorizing the basic pitch accent patterns that are associated with each individual vocabulary word. So, for people who use Anki, we made an addon that color codes pitch accents (and other stuff). Page 122 Assigning each pitch-accent a color is an idea that we took from the Mandarin community, actually. Humans have really good visual memories; if the word nihongo is blue every time you see it, you’ll unconsciously and naturally build a connection between the word nihongo and blue. Now, if blue means heiban to you, it just becomes second nature to pronounce nihongo in the right way. What’s the most important insight you’ve personally had into pitch accent? When you first learn about the patterns, you hear that the drop is the most important thing. That makes sense—each pitch pattern is literally defined by an accent drop (or lack thereof). The thing is, that’s not really what Japanese people listen for. Each pattern has its own unique feel to it, and your brain has to learn to identify these archetypal patterns/”feelings”. - Heiban has a sort of eerie, flat ring to it. Atamdaka has a big release of energy right at the beginning Odaka has a sense of building up to a peak, then suddenly dropping If you were to take a random word, plug a recording of it being spoken into Audacity and then look at the sound waves of that recording, there are times where it might not be clear from that information what the pitch-accent is… but the features of those “feelings” are still there. Getting better at hearing pitch-accent is sort of a process of internalizing these patterns. Say that I’ve got the basics down and I speak some Japanese. How can I start taking my knowledge of pitch accent a bit further? Start figuring out the major patterns that govern how pitch accent interacts with conjugations in order to cut down on the amount of memorization you have to do. There’s a really good explanation on the back of the NHK accent dictionary or Shinmeikai dictionary, but again, those are in Japanese. In a nutshell, - Verbs and adjectives are the only things that conjugate in Japanese So far as pitch-accent is concerned, there are only two types of verbs/adjectives We made an anki deck to help you memorize patterns associated with each conjugation of both kifuku and heiban verbs/adjectives On Learning Kanji What have you learned from observing the progress of people following MIA? Page 123 After working with many students, I’ve come to believe that there isn’t any single “right way” to get through the kanji. There are lots of different learners out there, there are lots of individual differences. The same thing might work really well for one person, but another would really struggle with it. It just depends on who you are, your upbringing and how you do things. For example, I used to recommend that people completed the original Rembering The Kanji book (RTK)—learning to write two or three thousand characters from memory—before doing anything at all in Japanese. Now, that’s possible, and it works. People who get all the way through it tend to find that, although they might have approached it differently if they could go back, it did give them most of what they wanted. They got through it and don’t really have issues with kanji anymore. As I’ve done consultations and worked with more learners, however, I find that it’s something that a lot of people really struggle with. They find it really tedious, boring, and generally difficult to get through. It’s an awful experience for a lot of people. Anyhow, what I want to say is that it’s not really a “one size fits all” thing. I do think there are certain principles that apply to everyone, but how you make use of those principles might differ. Kanji: All at once, or spread out over a longer period of time? I think it depends a lot on your goals. I like to break kanji up into two stages: ● ● Learning how to read (recognize the kanji when you see them) Learning how to write (by hand, from memory) In modern Japan, if you can read and you can speak, you can automatically type in Japanese. You just write out the hiragana and then choose the right kanji when it pops up, meaning you can work on a computer or text without being able to handwrite any kanji at all. They’re separate skills. So the real question for learners to ask themselves is: is it important to learn to handwrite kanji? I used to say yes… but now I think that, for most people, the answer is no. Even Japanese people have fewer and fewer opportunities to write things by hand because so much is done digitally in today’s world. The result is that people are forgetting to write characters by hand, and while people from the older generations might think that’s a bad thing because youth are getting worse at this skill… it’s happening because there isn’t a need for it. Now, there are certain situations where you do have to write things out by hand. You might have to fill out paperwork or something… but in those cases, you can just look the characters up on your phone and then copy them out—even natives do that. So, practically speaking? Being able to write out kanji from memory isn’t really that important. Page 124 But, some people might still want to learn to write the characters. I’m not going to say don’t do it. Some people might be interested in calligraphy, enjoy writing, or think it’s a valuable skill. And that’s perfectly fine. What it means for learners is just that it’s necessary to make a decision: If you eventually do want to learn to write things out by hand, you’ve got two options: ● ● First learn to read/recognize the kanji, then learn Japanese, then learn to write the kanji Learn to read and write all the kanji before you begin learning Japanese. Option two is possible, but it’s hard. If you don’t know Japanese, you’re not going to have any connection to these characters. Just reflecting on how RTK works—it’s demanding on your brain to connect the strokes of a kanji to what are sometimes arbitrary English keywords—wait, was this the kanji for angry? Mad? Furious?—At that point it’s not even an issue with the kanji itself, it’s a matter of keeping track of similar and arbitrary keywords… that aren’t even Japanese. I recommend that learners do the bare minimum so that kanji won’t be an obstacle for them as they continue their journey through Japanese, and then later on, after they’ve got a good foundation, to go back and learn to write the characters. Learning to recognize the characters is pretty easy, and learning to write the characters once you know Japanese is pretty easy because you’ll have seen them so many times in tons of different situations. The end result is the same, it’s just much less painful of a process when spread out. Past a certain threshold, can you learn characters on the fly as you go? Well, let’s start by qualifying the word learn. - A lot of people think that you either know a kanji or you don’t, in a very black|white way. I think it’s more like a spectrum: how deep is your knowledge of a given character? ○ On one end, you can sort of recognize it. When you see it, it looks familiar. ○ On the other, you know all the readings, meanings, can write it out by hand, etc. How much “kanji infrastructure” do you feel you need before you can start learning words? You can move on at a pretty low point along the spectrum—just being able to distinguish this character from that one, to recognize it as this character and not that one, is enough. If you reach that point, you can move right on to learning words. And given the nature of kanji, as a natural result of learning vocabulary, you eventually will naturally get a hang of the individual kanji readings, too, despite never having made an intentional effort to actually memorize kanji readings. Page 125 For example, say that you learn the words 明確 (meikaku), 説明 (setsumei) and 明治 (meiji). Now you’re reading and you see 発明... how do you think that 明 is going to be pronounced? Mei! Now, we never put 明 - mei on a flashcard, but your brain is a pattern recognition machine. So long as you give it stuff to work with, it can connect a lot of dots by itself. As you continue to grow your vocabulary, you’ll eventually develop an intuitive understanding of kanji readings. I think learners should do the minimum amount of pure kanji study necessary to jump into actual Japanese content. I’ve whittled it down to 1,000 kanji that cover 90% of all written Japanese. - Learn the character well enough to recognize that you’ve seen it before - Ideally, you’ll also be able to recall one of its meanings in a rough sense - We’re not worried about the readings, only the meaning of the kanji - The most important thing is reaching a point where, when you see a new kanji, it isn’t just a random blob of lines. It’s got a certain distinct form that you can recognize. Once you finish those 1,000 kanji, you can start focusing on words: - - - - You still don’t know readings, you’ve only got a rough idea of the meaning of the characters you know and there are many characters you don’t know… but you’re at a point where if you want to learn a word, you can isolate and memorize the characters in it. You start memorizing the meaning of full words without worrying about the readings of individual kanji. As long as you can read every word, you'll be able to read Japanese. But, after a while, you will find that you’ve naturally picked up many individual readings, too. After you see enough words, you start picking up this information automatically. And as you learn more words, you cultivate an ability to make logical guesses about how a given kanji in an unknown word will sound. Eventually you do reach a point where you can just list off readings, and you can pull them out of a hat. You never really memorized that, though, it’s just something that you learned naturally through experience in Japanese. Rather than memorizing all that information out of context, you did it in a way that plays to the strengths of your brain. Instead of just memorizing random information, you’re problem solving: You’re trying to read real Japanese, and your brain will step up and do what it needs to solve that problem. On The Role of Anki What’s the role of Anki for a beginner vs intermediate vs advanced student? At the beginning, when you’ve got no foundation, it’s very hard to learn anything at all from immersion alone. So in the beginning you’re using the SRS to help you get this structure, to build a base of basic grammar structures and one or two thousand common words. What might be surprising to someone new to language learning is just memorizing a word doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be able to recognize it when you stumble across it. I go into this more in my Page 126 video why you still can't understand your target language, but it basically boils down to this: Knowing a word—having conscious knowledge of its existence—is not the same as having the skill that is being able to pick it out of native speech and intuitively understand it, or of being able to pull it out of our brain on the spot to express a certain idea or emotion. Learning the words in an SRS is a good start, but it won’t take you to the point people think of when they think of “fluency”. Again, there’s a spectrum of knowledge for words : - At first, we simply memorize a word. We’re aware that it exists. - As we continue to listen to a language, we begin hearing it, but it often goes over our heads - Eventually we can pick it out consistently, but might not understand why it’s being used - After enough exposure you’ll reach a point where you can understand it effortlessly and know exactly what it’s doing whenever you hear it used - Way down the road, you become able to confidently use it yourself I mean, take the word okoru, to get mad. If you look up a translation of it and know that it means to get angry, that gives you a pretty good sense of what it means. You’re much better off than someone who didn’t know the word at all. Having said that, it’s still pretty vague compared to a Japanese person’s understanding of the word: the stuff that does and doesn’t count as okoru’ing. It’s kind of like carving a statue out of a marble slab. When you learn a new word, you get a new slab of marble. Just being aware that it exists means that you’ll be more likely to notice it while immersing. From there, every single time you see it used, you chip a little bit away to reveal the unique statue lying underneath the marble’s surface. But that takes time, and you only get that understanding of the word by seeing it used in tons of different contexts. So, if we bring this back to the levels you mentioned above: - A beginner has such a small foundation in Japanese that they’ve got nowhere to put these slabs of marble and thus need something like Anki to help them get started. - An intermediate learner is someone who has reached a point where they’re familiar enough with Japanese that they can start picking stuff up themselves by immersing. - An advanced learner picks stuff up just by naturally engaging with the language. They’ve got such a strong foundation in place that new information fits right in, effortlessly. So, past the beginner level, should you keep using Anki? That depends on your personality, really. - Some people really like Anki. It gives you a sense of security—so long as you make a card, you can be almost certain you’ll never forget that word. It gives you statistics so you can track your learning and also is a consistent thing to work into your daily life. Page 127 - Other people hate the SRS. It seems really regimented, it feels artificial and its opportunity cost is time that could be spent engaging with and immersing in actual Japanese content. I think that the intermediate stage is where you’ll really see people starting to split off and go their own way. Some people will be relying on SRS tools less and less, investing all their time into content, and others will keep up with their SRS regimen. Whether or not you keep up with Anki, I think it’s important to bring up the diminishing returns involved in using one. - The first 1,000 words you learn is huge in terms of bang for your buck. You go from 0% vocabulary coverage to 80% coverage. As you learn more words, the relative value of each word in terms of the % coverage it offers you becomes exponentially smaller Someone at an advanced level needs to deal with such a massive amount of words that it just isn’t practical to rely on an SRS to learn new words. The amount of words you need to know to approach a native level increases exponentially, but with Anki, you progress linearly. So I think that SRS is incredibly valuable during the early stages of language learning, but as you become more proficient, it begins making more sense to move towards immersion. Does that mean that advanced learners have no reason to use Anki? No, not necessarily. Even at an advanced level, you can still get value out of an SRS. - Maybe you keep track of super rare words Maybe you use it to learn the names of prefectures, names, foods, etc Maybe you use it for technical vocabulary that occurs very frequently in the content you enjoy consuming, but less frequently in daily life Generally speaking, SRS is helpful for filling in weaknesses The SRS is a lot like one of those machines in the gym for targeting specific muscles. You might have some body builder who’s like oh, this one little tiny muscle in my back isn’t big enough! And so he goes to the special machine which targets that one specific muscle. That’s an SRS. But for most people, who are content with being healthy, those machines aren’t necessary. In other words, if you just want to be a pretty good tennis player, you can just play a lot of tennis and you’ll naturally build the muscles you need. If you want to play competitively you’ll need to go further than that, but for most people, you can learn by doing. Page 128 Of course, we come into Japanese way below the level of “being able to run around and swing a tennis racket”, so to speak. So it’s not quite that simple when it comes to learning a language. Imagine that you just woke up from a coma and you’d been bedridden for like ten years. You’d have lost almost all of your muscles, so you couldn’t just get out of bed and go play tennis. You’d have to start off with physical therapy at first: very artificial, very controlled. As you progress you’d begin transitioning to part therapy and part daily life. Eventually you could focus on playing tennis. You don’t need to do that. You could be like a baby and just jump into the wild, but I don’t think that’s very efficient and it would probably be frustrating. We use an SRS and rely on it heavily at first to build a foundation, then we gradually wean off of it once we get to a point where we can start growing from real life. But maybe keep it up if you like the habit or want to be Roger Federer. On The Journey The ‘path to mastery’ is not a linear line A lot of people think that progress is linear so they don’t really plan their journey, thinking that they’ll just start walking now and decide when to stop walking later on. The issue with this sort of thinking is that the ‘path to mastery’ is not a linear line; there are a multitude of lines. If your goal is to reach a level of mastery, your first year will look very different than someone who just wants to reach a basic level of conversational fluency. I think that there’s a certain threshold of knowledge and your route depends on whether you see yourself landing above or below it: do you want to be able to consume media without subtitles/translations comfortably and have conversations without feeling handicapped? - If yes, the approach you take should reflect that from the beginning. It needs to be much more thorough, something more than just memorizing random phrases. If not, a thorough approach might not be necessary. You don’t really need kanji or a high level of comprehension if you’re just going to go to Japan as a tourist. How can somebody without a background in linguistics or experience learning another language know what level of proficiency they need to reach before getting started, though? I would recommend trying to have conversations with people who have learned a language to a high level; or at least look around on YouTube. I made a video a few years ago where I reflected on literally everything I did from zero to that point, for example. So watch that and ask yourself: - What stuff would you be excited to do? Willing to do? What stuff seems like a bit of a stretch, or even a waste of time? What is important to me, what goals do I have, how much time am I willing to put in? Page 129 I think that part of this problem stems from the fact that people think fluency is like a switch where before a certain point you suck and after it you’re perfect. The issue is that proficiency is a spectrum, and different people place “fluency” at different points along that spectrum. Furthermore, if you look at native speakers, even though they’re all “fluent”, some are much better writers or speakers than others. Personally, I think about fluency in terms of a 6-Point Model. A few things to think about: - - Not a lot of people are really talking about the realities of language learning, because most language learning tools that people come into contact with are just marketing fronts for a product, and their goal is to make money. Your actual learning comes second. When looking for someone or something to follow, be wary of The Fluency Illusion. The fact that you can’t perceive mistakes being made doesn’t mean they’re not being made. It’s difficult to know what’s possible before you know what exists, and that’s always going to be a problem: you can’t know what it feels like to be [X-degree fluent in Japanese] until you’ve reached that level of fluency. Concluding Thoughts Is there anything you’d like to bring up before we finish talking? Recurrent mistakes to avoid, important habits to build, that sort of thing? - - - I think it’s important to get in the habit of immersing in Japanese as much as possible. Whatever you’d like to consume after you’re fluent? Start doing that right now. That is easy for some people, difficult for others. It really comes down to your tolerance of ambiguity. Eventually you’ve got to make the leap of faith, jump into the ocean and learn to swim. No matter how much you study, you won’t ever become 100% prepared for real Japanese content. If you’re waiting until you’re ready to start immersing, you’ll be waiting forever. We put a lot of importance on understanding in the west. You’ve got to understand A to move onto B and C etc. And as an adult, we’re used to understanding everything and often on a pretty deep level. That leads to people thinking that they can’t read manga because they won’t understand all the words or grammar... but learning doesn’t have to be like that. I think children can learn so quickly, in part, because they aren’t afraid of not understanding. They still enjoy the movie even if they didn’t catch everything. Cultivate that sort of childlike mindset and gett better at being okay with not understanding: focus on and celebrate what you do understand, even if it’s only a word here and there. If someone ignores everything in this interview but one thing, what should it be? Page 130 Spend just a bit of time each day or week—the key word is each, it should be a regular thing— trying to tackle a piece of content in real Japanese. All that stuff that you’d be watching or reading if you spoke perfect Japanese? Start trying to do that stuff right now. At worst, this is just a reality check, reminding you what real Japanese is like. At most, it’ll change everything: one day, you’ll realize that you are ready for real content. Doing this ensures that you don’t waste time by waiting too long to begin immersing. (sound familiar? This is basically the 50% rule that I mentioned on page two, line one. It’s important!) Nelson Dellis on Memory and Language Learning [will integrate into kanji/vocab sections in v2] Page 131 Brian Rak on Making a Living with Japanese Brian Rak combined a passion for Japanese with his professional skills as a software developer to create content for people learning Japanese. Here’s a quick self-introduction from him: Brian Rak has been sharing his passion for the Japanese language since 1997, when he started writing short breakdowns of tricky grammar points online. The positive response he received from readers encouraged him to create larger and more ambitious learning resources, including Human Japanese, Human Japanese Intermediate, and Satori Reader, the latter of which consumes his full attention today as developer, editor, and annotator. Drawing inspiration from ray-of-sunlight voices like that of Jay Rubin, Brian's goal has always been to present the nuts-and-bolts of Japanese in a warm, down-to-earth, and humorous way. He sincerely hopes that Human Japanese and Satori Reader will play useful roles as guides on your continuing journey. Now, this interview is a bit unique. Whereas previous ones focused on providing actionable advice for specific issues, this one tells the story of somebody who fell in love with Japanese and made a career out of it. At first I wasn’t sure how it would fit into the document: everybody has different dreams and skills, so I doubt many readers will be able to follow in Brian’s particular footsteps. Having said that, we ended up talking for 90 minutes instead of the original 30 I’d planned. I’m pleased with how this turned out because I think it highlights the hurdles and practical considerations that go into making a career out of a language, but maintains an encouraging tone. While I don’t know what your future looks like, I do think these things are worth thinking about. Note: I asked Brian a few open ended questions and just let him go, so unlike other interviews, I can’t signal as well what information is where. To remedy that, I’ve opted to highlight some things. - Orange Background: Tips for getting off your feet as a business Page 132 - Green Background: Stuff that particularly stuck out to me and I want to highlight Key Takeaways: Knowing Japanese is great, but it's even better to know Japanese plus something else. In my case, that's Japanese + software development. If I didn't have the software experience, there's no way I would have been able to build Human Japanese and Satori Reader. It's important to have another tool in your belt besides just pure language ability. - Trade Offs: It isn't the most lucrative route to take, and you’ve got to figure it out as you go. Luck: There’s a right place and a right time. Watch out for it, and be ready when it comes. Patience: Brian released his first course in 1999. It didn’t become his full job until 2009. Toilsome: Being an entrepreneur means wearing many hats; some you like, many you don’t. Consistency: It’s essential to push the ball forwards every day, even if you can’t do much. Teamwork: You can’t do it all by yourself, so learn to work in a team. Brian’s Background So, I guess the natural starting point is to ask how you got into Japanese, yourself. I had been fascinated with foreign languages, and Japanese in particular, since I was a child, but didn’t begin studying it until high school. When I did begin studying formally, though, I really fell in love with the whole process. By the mid-point of my second year studying Japanese in high school, I’d already made the decision to be an exchange student for my senior year, which made me even more energized to study. I wanted to be ready to make the most of my time in Japan. When I arrived, of course, I discovered just how little I knew. At the same time, it was also amazing to see the things that I did know constantly popping up all around me. To see this stuff that I’d been experiencing in a textbook suddenly come to life. I also began to appreciate just how insightful the explanations from my high school teacher back home had been. I often found them ringing in my ears as I navigated the language. He really influenced me, and it was about that time that I began thinking that maybe I wanted to teach Japanese, too. And now you make a living off of Japanese. What all happened in the meantime? When I returned home I started a blog on Geocities and began writing about Japanese. I hadn’t expected much, but then people began writing to me and commenting that, because of what I’d written, they understood something for the first time. That was a really encouraging feeling, and I decided that I wanted Japanese to play some role in my life. Maybe I really would become a professor. There wasn’t any money involved back then, though. It was purely for the love of doing it. Page 133 Anyhow, I went on to college, decided to study Japanese and also started experimenting with Human Japanese, my first major project. Money began getting tight partway through my third year, so I decided to take my first leap of faith: a semester off. I basically holed up in my bedroom for nine months and put together the first version of Human Japanese. During this time I also re-discovered how much I enjoy programming, and I decided I wanted to do more of it. So that’s how I came to my two major passions, in a nutshell. Japanese and programming. What is this “Human Japanese”, exactly? Like I said, it was my first big project with Japanese and programming. I’d originally intended it to be a textbook in the style of Gone Fishin’ by Jay Rubin, which is a collection of grammar essays. They’re interesting, funny, witty… I’d literally be laughing out loud while reading his grammar explanations. I wanted to make something like that, but for beginners. So anyhow, like I said, I had played around with programming as a kid. I wrote Human Japanese, put it in software format and ended up selling a few hundred copies over the course of several months. Not an outstanding success by any means, but it did show me how much I enjoyed programming and also led me to an important realization: Huh, I’m going to need a real job, too! (Sui: he didn’t actually mention it, but you can still visit Human Japanese’s website, if you’re curious. Also, Jay Rubin is great, if you haven’t heard of him! I’m currently reading his (English) biography of Murakami Haruki and it’s a delight. I recommend it to anyone planning to read Murakami’s stories.) The programming experience I gained was enough to win me a job with Microsoft after graduating. I started out as a contractor, then as a vendor, and eventually became a full-time employee. I was there for seven years, all the while keeping up with Human Japanese on the side. Trying to improve it and make it better. And then the iOS store came along, which turned out to be another major piece of the puzzle. Getting your name out there used to be very difficult. Search engines weren't very good and I hadn’t established an online presence yet, so people would just occasionally stumble onto Human Japanese or my Geocities site. YouTube wasn’t a thing, and there wasn’t really anything like Facebook where you could engage with people and promote yourself. That in mind, the App Store was sort of a revolution in terms of the reach it gave you. I launched one of the first Japanese-related applications that took a narrative/grammar centric approach, describing how the language works. We got ahead of the competition, and Human Japanese was also pretty novel, compared to what else was on the market. We got lucky, basically. Putting that into perspective, though, Human Japanese was a lifetime purchase of $10.00 USD. Apple takes a 30% cut, so that means that my lifetime revenue for each purchase was $7.00 USD. That’s not a lot, but I decided to take another leap of faith and left Microsoft in 2010. Page 134 I’ve been working on my projects full-time ever since, and that’s where Satori Reader enters the picture. The Reality of Self-Employment Satori Reader is what led me to reach out to you, actually. So now you make a living off of something that combines your passion for both Japanese and programming! How’s that? It’s a massive endeavor, to be frank. Much more than full-time. But it’s a labor of love. (Sui: I’ve been surprised in that a lot of Brian’s comments have really resonated with me, but this comment was very relatable. Originally this document was just where I would keep track of answers I gave to common questions. One day I realized that if I fleshed it out a bit, it would be almost readable. So I did. Upon publishing it I began receiving feedback and suggestions—this part could be organized better, a common question I didn’t talk about, etc. Some stuff I could handle myself, others I couldn’t—so I began doing these interviews! What I thought would be a few hours of work became a yearlong project. It’s cool, but it keeps growing… like Brian said, a labor of love). It was a significant change going from an office at Microsoft to working independently, and I also took a substantial pay cut in doing so. But, anyhow, I just focused on gradually growing the projects and expanding the team over time. Finances still present a challenge—there are so many ways I’d like to grow the products, simple functionalities I’d like to add, take steps to make it look more professional and mature, etc. But, anyhow, we push the ball forwards a bit everyday, and I’m proud of how far we’ve come so far. (Sui: Just for a bit of context, Satori Reader is an interactive and intelligent source of graded reading/listening material. Brian and his team put out several series in Japanese—slice of life, horror, drama, a bit of everything. Each episode of the series is presented as an interactive text. Clicking on a word brings up a pop-up dictionary, and Brian reviews each text to see which points might confuse an early learner. He goes to pains to explain the nuances of all these points that a beginner might not pick up on. To top it all off, each episode is narrated by a professional voice actor) But what is the workload like? What does a day in your life look like? One of the biggest time investments is content. We push out three new articles/episodes each week. They’re put together by a two person team (one writes, the other edits). After that I take a sweep, editing it from the standpoint of how the text would look to an earlier version of myself. What might seem easy or normal to a Japanese speaker, but is actually kind of tricky for a learner? Type stuff. I also do all of the translation and captioning. Page 135 The graphic design is done by a longtime friend that I’ve been working with way back since the days of Human Japanese. I gave him a royalty agreement, which basically means that he does all the work up front for free, but then he gets a slice of revenue later. This is a great option for people just getting started without a lot of capital on their hands, as it lets you spread out of getting your project up and running. It’s also smart from a business perspective, as it creates a situation in which the long-term success of your product is beneficial to the people you’re working with, too. From there each article goes to an editor in Japan, who we pay on an hourly rate. After the stories are finalized we get them narrated by voice actors—a few really great people who believed in our product and were willing to give us reduced rates in the beginning to help us get started. That’s another thing worth thinking about—it can be hard to find enough work as a freelancer. The promise of long-term work was attractive to them, and the cheaper rate helped my team and I to get our feet under us as a platform. Then, the nature of being a small business is that you wear many hats. I love programming, but only about 30% of my time is spent writing code. There are just so many administrative tasks to work on, and as the product grows, so does the time commitment that entails. I suppose I spend 20-25 hours a week on work related to Japanese, primarily preparing content for the website and replying to questions that people have asked about the articles. The rest of my time goes to website and app maintenance. Random little problems pop up all the time. What would you say that your biggest difficulties are, as a small business? Finding enough hours to move the programming ball forwards. So far my approach has been to work hard on the content production in short bursts. I’ll get ahead of schedule on that, and then I’m left with a week or two where I can focus purely on programming. Your Take on Learning Japanese Could you tell me a bit about some of these “nuances” and “features” you’re talking about? What can someone get from Satori Reader that they couldn’t get reading on their own? Well, like I said, I love Japanese and I’ve spent a lot of my life learning it. I’ve also spent a lot of time working with beginners. That means that I’ve developed a good eye for things that a beginner might struggle with, and I’ve also gotten sort of a knack for explaining those things in an accessible way. So, like I said, I read through the stories that our writers create and then add in annotations that will help a beginner to make more sense of what they’re reading, to smooth over difficult points. Or simply to point out stuff that might go over a beginner’s head without them realizing. Page 136 For example? Well, everybody has a dictionary these days and they’re very convenient to use. So when I’m reviewing our stories, my goal is to go a bit beyond the dictionary. For example, off the top of my head, here are a few things I highlighted in a story recently: - Sentence Breakdowns A major goal of Satori Reader is providing learners with the foundation and confidence necessary to tackle some of the incredible books within Japan’s body of literature. To that end, once every couple episodes, we work a particularly long sentence into the story. We hope this will help learners to gradually acclimate to the more complex structures they’ll encounter in real content, and it also gives us an opportunity to really explore what’s going on under the hood of Japanese grammar. Maybe there is a long relative clause. Maybe there is が→の substitution. Maybe it’s some other little subtlety of language that a learner might be unfamiliar with. I like to take these sentences and say, "Hey, let's break this down together.” First I point out the very core of the sentence, then point out what each other part of the sentence is describing. From there we gradually work our way up to the full, original sentence that we saw in the main text. Readers seem to really enjoy these, and I hope that after they’ve watched me break enough sentences down, they’ll become more confident doing it themselves, too. - Ambiguous Readings Sometimes it’s impossible to tell how a word should be pronounced without context. If you look 開くup in the dictionary, for example, you’ll see both ひらく and あく. That can be tricky to process, so I just include a small note—hey, in this case we need a transitive verb, so this will be pronounced ひらく—accompanied by a quick review of what transitive and intransitive verbs are. Another example is 汚れる, which can be read as both よごれる and けがれる. Whereas よご れる refers to being literally dirty, like the air isn’t clean, けがれる is more of a spiritual defilement. To be violated or corrupted. That could throw you for a spin, so I just make a quick note. No worries, this isn’t a demonic coffee table or anything. It’s just got a bit of a stain. - Parenthetical Omissions A particular reason that Japanese can be difficult to break into is that parenthetical information often gets omitted for the sake of brevity. While we communicate quite directly in English, Japanese often feels that the context of an event will be obvious to people involved/following along, thus making it redundant to explain. Page 137 So take a situation where a stalker breaks into someone’s house. Nobody is home, so they walk into the kitchen and start making pancakes. A nice after work snack for their to-be suitor. Suddenly the door opens, the person who owns the house walks in and they see this stranger standing in their kitchen. Upon meeting eyes, the stalker might just say 勝手にごめんなさい, which is short for 勝手に (部屋に入って)ごめんなさい, which is still short for hey, yeah, sorry that I just all up and walked into your place uninvited and started making pancakes. It’s just expected that a Japanese person would fill in those blanks naturally, but it can be a struggle for learners—unless you’re really dialed in to what’s going on, oftentimes the omission of this parenthetical information can make stuff seem like it comes out of the blue unannounced. (Sui: The above is me summing up Brian’s comments very roughly. If you’d like to get a more true-to-life sample of the sort of explanations Brian has to offer, here’s a video he put together in order to explain the ~てみる and ~ようとする structures to one of Satori Reader’s users.) To be honest, putting these notes together is probably the most enjoyable part of this entire process. People leave little comments like oh, that makes sense, I finally understand that now!—so I get to sort of vicariously enjoy someone else’s lightbulb moment. At the end of the day, I think that’s what all of this boils down to, really. It’s awesome to see that your work has touched someone. If you don’t get that validation, it’s sort of like you’re living on a desert island. Surviving, you’re here, but there just isn’t much evidence of it. Anything interesting that you’ve learned along the way? Something surprising, maybe? One big surprise for us was just how important stories are. Originally we planned to just write dialogs and news articles. But we quickly discovered that stories have incredible value because they draw you in and give you additional motivation to keep reading. Let's face it: studying language takes a lot of effort, over a sustained period of time. Anything that can keep you doing it is worthwhile. So if you’re invested in a story and that encourages you to keep coming back to Japanese, to see what happened to a character, that helps. Plus, a story makes everything more real. Especially when backed by a good voice-acting performance. You know, what does a word mean? I mean, what does it really mean? How does it feel? When a word is just an abstract thing, it's sort of soul-less, like an empty bag. But when you learn it in the context of a story, or because a character you care about used it while trying to achieve something, or as part of a documentary about a topic you cared about, suddenly it becomes important, something real. It goes from being a random word and becomes part of your world. Page 138 Regardless of whether people use Satori Reader or something else, any opportunity you have to move language from the sterile confines of a review app or a textbook and into a place where it has consequences is incredibly valuable. Closing Thoughts I saw a motivational video a while back. A key message of the video was that “to succeed, you need to want [whatever you’re doing] as badly as you want to breathe”. What do you think? Well, sure. No matter what you’re doing, you have to want it. You have to love it. There isn’t any money in it immediately, perhaps never. If you aren’t able to make ends meet with Japanese (or whatever it is), that means you have to make time for it and be prepared to do it on the side. At the end of the day, it comes down to this: Would you be happy knowing that you produced something that was valuable, in the sense that it helped people? Even if it didn’t earn you money? (Sui: I’m currently reading a book by the existentialist Viktor Frankl called Man’s Search for Meaning. In the preface to the book there was a line that really resonated with me. Success, like happiness, cannot be pursued. It must ensue. — I think that success is a byproduct of committing to something you love). What would you tell someone reading this who is thinking about pursuing a career that involves Japanese? I’ll just say that, while I love Japanese, I’m grateful that I have my other skills, too. Programming, namely. It’s just impossible to know how the world is going to change, so I think the need to be competent in something (anything) not related to language is very real and pressing. I worry about AI, for example. Will people need to study languages if we have instantaneous human-quality interpreting available? To approach this from another direction: Knowing I have another skill that will enable me to pay the bills if Satori Reader fails is what gave me the courage to make this leap of faith, initially. You’ve got to go for it all if you want it, and knowing that I could always just go back to Microsoft gave me the confidence to take a much deeper dive than I would have, otherwise. So, it’s not necessarily a Plan B. Just another thing that you’re competent in. Even if it feels like a Plan B, all it’s doing is putting a bit more gas into the tank of Plan A. Knowing Japanese is great, but it's even better to know Japanese plus something else. Page 139 Human Japanese and Satori Reader Human Japanese presents the Japanese language from square one, in a warm, conversational manner. While focusing on the nuts-and-bolts, it uses humor and cultural asides to keep the lessons fun and motivating. Its sequel, Human Japanese Intermediate, provides a seamless transition to the next level of Japanese, introducing more complex sentence structure, kanji, and thousands of example sentences to tie everything together. Learn more at https://www.humanjapanese.com. Satori Reader provides learner-friendly Japanese reading material with sentence-by-sentence audio recordings, inline notes that break down tricky passages, a built-in flashcard system, and a unique presentation engine that uses kanji and kana according to a student's individual knowledge and preferences. Learn more at https://www.satorireader.com. Appendix On Learning Generally speaking, I’m a big believer in using Japanese rather than preparing to use Japanese. To that end, I’ve done my best to link you to stuff only once it becomes relevant to what you’re doing at each stage of the timeline. I don’t want to waste your time with stuff that you don’t need, and I don’t want to go to the trouble of finding resources that nobody else will use. Unfortunately, even after a lot of spring cleaning, I still found myself with some stuff that I wanted to share but wasn’t sure where to put. That in mind, everything in this section is either: 1. Foundational; I think it provides context important to the document as a whole 2. Giving me a headache; I think it’s important, but wasn’t sure where else to put it. If you’re really going to give me such power over your life as to let me play a hand in blocking out the next year of it, please take a bit of time to look into where the ideas I’m presenting to you come from. It would be unfortunate if you disagreed with me on a fundamental level but only discovered that six months from now. First, two general suggestions about approaching this document: ● Appropriate and repurpose my timeline to fit your needs—or even discard it completely if you really feel uncertain about something. This is your own learning. ● I’m about to list 13 suggestions of stuff I think would be beneficial to look into before you start with day 1. For here, and for every other page of the document, I’m absolutely not expecting all of this to be done in one sitting (or even at all). Page 140 Break it into multiple sessions, read one per day, anything goes. You know how you work. So, anyhow, here are things that will help you to learn Japanese, although they aren’t explicitly resources for learning Japanese. 1. See Bakadesuyo’s compendium on Achieving Goals: Everything you need to know Learning, in some sense, is a process of consistently achieving goals. But how do we actually achieve goals? This is a repository with dozens of links about doing so, most of them connected to scholarly articles and published books you can look further into. Just take a gander and click on anything that seems interesting. We’re constantly setting goals in one way or another, so take some time to learn how to set better ones. 2. Check out Kolb’s Learning Cycle Learning isn’t just something that happens; it’s a pretty well documented process. Take some time to figure out how learning works so you can go about it in a way that is actually useful for you. I like Kolb’s model, and I think it helps put the concepts of input and output in context. If you’re missing any of these four steps, you aren’t learning as effectively as you could be. Kolb’s Learning Cycle: The four steps we must go through to learn anything ( p1) Kolb’s Learning Styles: The four different styles of learners (Relevant: Take the Time to Learn How to Learn) 3. Get to know Hermann Ebbinghaus and his contributions to the study of memory Memorization is an unavoidable part of language learning, and if you’ve ever spent 5 minutes on a language learning forum or Googled for advice about better memorizing stuff, you’ve almost certainly stumbled onto ideas that have roots in Ebbinghaus. For now, I’d like you to just ponder over a few of his major ideas - The Forgetting Curve: You’re going to forget pretty much everything you ever learn, and over the course of just a few days at that, but we can strengthen these memories. Hermann advocates for the use of spaced repetition (the idea that tools like Anki and Memrise are based upon - in 2 min or 26 min) and mnemonics. and mnemonics (little stories to help Page 141 you remember stuff -- Never Eat Shredded Wheat). - The Learning Curve: Have you ever heard something referred to as having a steep learning curve? If so, you’re familiar with Ebbinghaus. No matter how smart you are or how serious you approach learning, you’re not going to master this on the first try… but most things get easier with time and/or trials. - The Serial Positioning Effect: We recall the first and last item in a series better than items in the middle of it. In other words, it’s good to break up your studying across multiple sessions - doing so gives you more first and last items. (aka the ‘priming’ and ‘recency’ effects) 4. Check out some timelines/reflections put together by other people You’re about to read my timeline, and it’s heavily steeped in my personal biases and preferences. Yours might not be the same. Plus, my resources might be a bit outdated: I haven’t followed new apps about learning Japanese for three or four years. Check out what other people think to get a better feel for what is established advice (ie, it’s not just me saying this) and then what stuff is just me going off on my rocker. I’ll periodically update the below list with new content as I stumble into it. I will also include links I’m directed to if they aren’t low-effort cash grabs (ie, if you’ve written something that you think should be included here, PM me a link on Reddit). Stuff with a product behind them - [How to] Learn Japanese Online by Cure Dolly - Walkthrough - Your Journey through Japanese by Japanese Level Up - 365 days, 500 hours of Japanese by u/Kidvibe - Hacking Japanese Supercourse by u/Nukemarine (see also: LLJ / SGJL ) - Learn Japanese: A Ridiculously Detailed Guide by Tofugu Other peoples’ timelines - - Acquiring Japanese Efficiently by Dylan Robertson All Japanese All The Time (AJATT) by Khatzumoto A Ridiculously Detailed Guide by Tofugu Awesome-Japanese Guide & Resource Dump by [folks at GitHub] Genki Survival Guide by u/Kymus How I kinda okay at Japanese in 24 months by u/Renalan Page 142 - - - IC’s Japanese Roadmap by [group?] Japanese the Moe Way by [Moe] Learn Japanese - A Six Step Study Plan by KumaSensei Migaku Minimal Guide to Learning Japanese by u/Foodhype My Japanese Year-in-Review by u/Romelako Passing the JLPT in 1.5 years by stevjis3 [his progress log] r/VisualNovel’s approach to Japanese Refold Resources I gathered from a year of learning by u/Soorya23 Resources by JLPT level / JLPT study guides by u/[Deleted] :’( TL;DR / Megapost for the Self-Learner by FestusPowerLoL The Best Way to Learn Japanese by TheTrueJapan Two Years of Japanese Resources (II) by u/Jo-Mako Two years of studying + a year in Tokyo by u/Oleandersun Vlog documenting 800 hours(1yr) of Japanese progress by Shawn People’s progress through this document - u/The_Real_Donglover - Month 2, Month 4, Month 6, Month 9 u/Khamazp - One Year in Review 5. Thinking about paying for something? If you’re thinking about paying for any resource, whether it’s one I’ve suggested or you’ve found yourself, please first do some research about it on All Language Resources (the hub for reviews of resources about language learning resources - here is how they do reviews) 6. Become aware of mindfulness in language learning I think that achieving a high level in anything requires being mindful. My favorite introduction to mindfulness is The Four Roads to Happiness by Osha Taigu (EN subtitles). The four principles of happiness shared in this video ultimately make up the backbone of my entire language learning philosophy. They are, paraphrased, as follows: - Some things make you feel good (productive, fulfilled, motivated, whatever); figure out what these things are, do more of them. Take steps to ensure that you can continue doing these things, or that you won’t enter a situation where you can’t do them (I like reading; I take a book with me everywhere, just in case I have downtime). Page 143 - Some things make you feel bad (burned out, regretful, whatever); figure out what these things are, do less of them. Take steps to ensure that you don’t accidentally wind up doing these things (I often sleep in till noon on Saturdays, my only free day of the week. I immediately regret this because… well... It wastes my only free day. It also throws off my sleep schedule for the coming week. I’ve begun scheduling iTalki lessons for 9:00 AM on Saturday. It forces me out of bed and ensures that my day begins with something important to me). Ideally, if you apply these steps, your learning will become progressively more tailored to what works for you. 7. Understand the Pareto Principle Not everything is worth your time; according to the Pareto principle, 80% of the value you’ll derive from this comes from 20% of the content. Depending on what you personally want out of Japanese, different parts of this guide are going to be more or less important to you. For example, pitch accent is a pretty hot topic in the Japanese learning community and it’s an important part of developing a natural accent. That being said, Steve Kaufman doesn’t worry about it because he “isn’t a perfectionist and is quite prepared to be imperfect in [some aspects of] a variety of languages… “ he says, “whereas in [Matt vs Japan’s] case, [he’s] focusing on one [language] and wants to be as complete as he can be in [Japanese].” Steve also prefers massive input to spaced repetition. He concludes, “All of these things are choices, and for different choices there are different solutions” For me, this is the main point of the Pareto Principle. - Understand what you want to get out of Japanese Do more of the stuff that moves you closer to that goal Do less of the stuff that doesn’t 8. A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Science and Math This is a super cool book about learning that is applicable to everything. I’ve already covered some of these ideas, but I’ll also list them here just for the sake of thoroughness. All of these are major concepts that will lead to more learning efficiency; work through them over time, see what resonates with you and try to incorporate them into your learning routine. - Active Recall - Test Yourself (I’ll just again suggest you read the stuff in point 3) Page 144 - “Chunk” Information (II) - Spaced Repetition - “Interleaving” - Take breaks in a structured fashion - Explanatory Questioning (explain what you’re learning by making a metaphor out of something else) - Focus - The 90/90/1 rule 9. How to make a behavior addictive Some habits stick, others don’t. Why? She introduces Tony Robbins’ six human needs and suggests that any behavior which meets 3 of the 6 criteria will become addictive. - Certainty: A certainty to avoid pain and gain pleasure. If you do X, you’ll get Y. - Variety: While certain, [thing] isn’t dull; there’s spontaneity and new engaging stimuli. - Significance: [Behavior] makes you feel special or unique - Connection: A feeling that you’re part of a community of people [who also do the thing] - Growth: While doing [thing], you get the feeling that you’re improving/progressing - Contribution: While doing [thing], you get a feeling that you’re helping others A lot of people dabble with languages and never really achieve any notable level in any. If this sounds like you, spend some time figuring out how the things you consider integral to your life meet these criteria. How can Japanese become significant, too? Do you even want it to? Does your life have room for another “significant” thing? 10. Figure out if you’re in love, or if you’re in “fish love” In a video discussing love, Rabbi Dr, Abraham Twerski points out an interesting way in which our language allows us to skew our perception of reality. You don’t love fish, he says, you love to eat fish. True love is a love of giving, not a love of receiving. Similarly, when we say “I want to learn Japanese”, I think that there’s more there than meets the eye. Very few people are really saying that they want to do the very pure and sterile thing that is learning Japanese; they want to do something that, for whatever reason, they feel they can only do in Japanese—or, at the least, that would be better done in Japanese. Whatever it is that you really want, you might not actually need Japanese to do that thing. It takes a long time to learn any language, and that’s a lot of time that you could instead spend on the thing that you actually want to do. Page 145 11. Read Alan Belkin’s Letter to a Young Composer I presume that you’ve opened a long and wordy document that you found on a forum of language learners because language is important to you. Maybe it’s a little too close to judge honestly. But any sort of learning involves a lot of honest judgments. Sergei Yesenin writes, in Letter to a Woman: nose to nose, our faces go unseen; we must step back for clarity. That in mind, this is Alan’s reflection on his life and career, and what he’d like to tell young composers who are just beginning to pursue music. A lot of his words apply equally to the journey you’re about to embark upon, and even if you can’t tell a violin from a snare drum, I encourage you to at least give it a skim. There is a lot of meaningful food for thought. If that’s too much to ask, at least check out this excerpt: At times, most honest composers of “serious” music, especially if they are not part of whatever clique is “in” wherever they live, ask themselves: Why bother? You are writing music which has no large public, which some of your colleagues may not even respect, and where the rewards are few. There is no easy answer to this one. But I can say that “real composers” write because it is part of them, because they love the music they write themselves. In other words, they love doing it. If you are also a performer, you will have the pleasure of playing music (including your own) all your life. And nobody can take that away from you. Making music should be an activity which enhances your quality of life, and which allows you to share what is best in yourself. It is worth quite a lot of work to make that happen. 12. The Golden Circle by Simon Sinek “People don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it. What you do merely serves as an indication of what you believe,” the key line from the most famous Ted Talk of all time. “We follow those who lead not for them, but for ourselves.” A while back I wrote a post entitled “Why Learn Japanese?” and my central goal with the post was to encourage people to think about why they feel they need Japanese in their lives, rather than some things they’d do if they were fluent. I think that this video does a better job of encapsulating what I had been trying to say. Nobody learns the piano because they want to become the new Bill Evans or Debussy; they learn piano because there is a certain song they want to play badly enough. And if they play enough songs, and make enough songs their own, they’ll eventually become a pianist. 13. Look into some linguistic theory. Page 146 People have been interested in how to best approach learning a language since.. well.. forever, probably. Take some time to skim the major approaches, then reflect on how/why they do or don’t align with your personal values. u/TottoriJPN condensed several major approaches into takeaways and TL;DR’s. - Learning Methods 101: Natural Methods - Learning Methods 102: Linguistic Methods u/Virusnzz has created an extensive starter’s guide that addresses many FAQs, provides advice on different aspects of language learning and introduces many key concepts. u/Nonebb has created an in depth outline of several language-learning strategies for different types of learners that includes further reading and supplemental activities. On Meditation Meditation and mindfulness are words that get thrown about pretty indiscriminately and mean different things to different people. I’d like to take a page or so to explain what these words mean to me, and more importantly, how they’re relevant to your Japanese studies. And your life, I guess. I introduced the section on listening comprehension by listing several issues that may impede your ability to understand what you hear; one of them was focus. I often found that I failed to understand something not because my Japanese was lacking, but because I’d space off while listening. I proposed meditation as a remedy to this, but I wasn’t flippantly throwing out a platitude. To me, meditation is a form of training with concrete stages and two particular goals: - Learning to focus; how to summon it, how to direct it, how to sustain it Improving awareness of what’s going on in the periphery To put that in terms more relevant to language learning: Page 147 - Focus: If you’ve even humored the idea of meditation, you’ve heard about following your breath. The breath is just a convenient meditation object—something you maintain focus on. However, anything can be a meditation object. If you learn to maintain undivided attention on your breath for 15 minutes, you can do the same with your podcast or flashcards. - Awareness: We process frightening amounts of information each day. In meditation, awareness involves realizing that your mind has wandered and then directing it back to your meditation object. With practice, you’ll immediately notice once your mind wanders. This enables you to study much more efficiently by minimizing wasted time. - Context: A big part of awareness amounts to appreciating context. If you recognize that you’re angry you can reflect on what triggered your anger and take steps to eliminate or minimize it. In language learning, this amounts to appreciating how people express their ideas and “check” your own thinking, enabling you to use the world as a textbook. If the above sounds attractive to you, start with the following book. 1. The Mind Illuminated: a very practical step-by-step guide to meditation. The author is a neuroscientist and breaks meditation down into ten progessive steps, each of which having concrete goals that let you understand when you’re ready to move on. If you find the above to have been useful and want to start applying it to your life at large, here are a few good reads on how mindfulness can be applied to all sorts of mundane, everyday activities. 2. The Happiness Animal: a lot of the book is re-packaged lessons from the stoic philosopher Seneca, but it does introduce five useful exercises. One in particular involves labeling your thinking links. Happiness or anger is a result; what led to it? What can you do about it? If you don’t want to buy the book, watch this video. They boil down to the same thing. 3. The Miracle of Mindfulness: an introduction to mindfulness combined with anecdotes presented by a monk that demonstrates how mindfulness fits into everyday life. It’s the book I would recommend to someone who is interested in mindfulness, but skeptical. From here, if you’ve also found value in exploring mindfulness, I recommend reading The Way of Liberation. It’s a brief (and free) introduction to meditation as a secular practice that does a good job of outlining key goals of meditation/mindfulness as a “lifestyle”, so to speak. From this point on, you explore. If you aren’t sure where to start, I recommend the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh. I find his writing to be very accessible, and he is excellent about introducing topics in a way that doesn’t alienate non-Buddhist audiences. He’s been a huge influence on me. ● No Mud, No Lotus: I struggled with depression for a long time growing up. This book is all about suffering: "When we know how to suffer," Nhat Hanh says, "we suffer much, much less." Page 148 ● How to Love: Part of a series called mindfulness essentials, in which Nhat Hanh offers suggestions into how to approach daily activities like walking and eating, this book is an exploration of love. It’s the only book I’ve ever read multiple times, and it changed the way I interact with people. ● The Heart of Buddhism: A comparatively denser read, in this book Nhat Hanh provides an overview of Buddhism, its goals and key concepts. Meditation isn’t a religious thing for me, so this wasn’t as valuable a read for me as the other books, but it did provide a lot of interesting context about practices that have become very dear and integral parts of my life. I’m here to help you with Japanese, not to tell you how to live your life. I don’t expect you to do any of the above. But if you’re interested, here you go. My Personal Schedule Originally, I intended to study only Spanish and Japanese and be satisfied with that. The nature of languages, fortunately or unfortunately, is that one often seems to lead to another. Now I’m juggling five languages (SP, JP, RU, CN, KR) and two other hobbies (piano/music theory and writing). I don’t think you should try to emulate my schedule, because what works for me might not for you and/or might not be conducive to your goals, but maybe it can offer you a few bits of food for thought. Regardless of all that, the juggling act centers around a few things: ● ● ● ● Environment: What languages are around you? How do they form part of your life? Do you actually need them to get through your daily life? Expectations: How proficient do you aim to become? By what time do you want to do so? Acceptance: You can do some things. You can’t do others. Accept both. Boundaries: Once you’ve established your expectations are and what you can/can’t accept, enact boundaries to ensure that those things are upheld. Anyhow, my schedule: - 7:20—Wake up, get ready for a 1hr FocusMate session. I do 30 minutes of yoga (sitting all day does a number on you) and spend the rest of the time doing Korean homework 8:45—Leave home, 25min walk to work. I listen to a Japanese audiobook during this time 9:15—Arrive to work. Spend 10 min going through a JLPT prep/grammar review book Page 149 - 12:00—I spend the first 30min of my lunch writing (this, or for r/DestructiveReaders) 12:30—30 min Skype lesson (CN on Thursday, KR on Monday and Tuesday) 17:40—I listen to an English audiobook about learning/habits/meditation/etc 18:30—I play piano for 30-45 min while my wife makes dinner 19:30—I listen to a short story while doing dishes 20:00—My wife and I study Korean together Bedtime—I meditate for 25 minutes, then read till I feel tired. EN/SP/JP, just depends Other stuff that doesn’t fit neatly into that timeline: - - Anki/KwizIQ—I’m a huge fan of timeboxing. Throughout the workday I do (6min:2min)x3 > 6min break sessions. During the 6 minute blocks I work, during the 2 minute blocks I do Anki (till I finish) then KwizIQ. I also do Anki while walking around/on the toilet/etc. Bouldering—On Wednesday nights I go bouldering with friends for a few hours, but we spend more time sitting and chatting (CN/EN) than actually climbing… LingoDeer—I’ll go to Korea 2023. I’m taking a slow, steady approach to the language, aiming to reach a low intermediate level before arriving. If I finish Anki, I do this. Taiwan—I live in Taiwan and work in a Mandarin-speaking office. I’m constantly drowning in Mandarin and sitting through meetings in Mandarin (that I don’t understand all of). Weekends—I don’t expect to accomplish anything productive on weekends. Hit or miss. Some comments: - - I’m big into interleaving (~90sec/4min/1200 words), and I like it because it helps me deal with procrastination. I’m passionate about language, reading, writing and music, but it comes in cycles for me. I just accept that and go with the flow. I might spend a lot of time learning about music for a couple weeks, for example, but eventually I begin feeling bored or run out of ideas about what to do next. When that happens I switch to the next thing. Typically, the “downtime” is enough time for me to become excited about some random new thing that will later kick off a new week or two of learning. The result is that I’m always making exploring something important to me… it just comes in spikes. There’s a lot I’d like to read in Russian and Spanish, but they aren’t relevant to my life in Taiwan. I treat them accordingly. I do something fun in them for an hour or two each week. I expect to stick with them long term and I accept that I can’t focus on them right now. Things you need to ask yourself: 1. Do you actually need any of these languages in your life? (ie, I need Mandarin for work. I can’t realistically go through my day without it.) 2. Do you feel so drawn to your language(s) that you go out of your way to consume content in them? (ie, I read in SP/JP even though I don’t use them in Taiwan) 3. Do you have any connection to your language(s) that forces you to use it regularly? (ie, My social life is in Mandarin, my wife is Taiwanese) Page 150 4. Is there anything concrete you'd like to do in your language(s)? (ie, I want to learn the hangul and a bit about Korean pronunciation—a small, well defined goal). 5. Do you lose anything if you fail to spend time in your language(s)? (ie, if I sleep through a lesson on Sunday, I’m out a few dollars.) Think about these questions in order to define your “juggling act” (which likely includes non-language things, too) and then enact boundaries to ensure you can keep the act up. Personally speaking, I found the following things to be very helpful in doing that: - Habit triggers and trigger-action plans How to make a behavior addictive and the six human needs Timeboxing, AKA how to deal with procrastination FocusMate: Schedule when you want to do an hour of work, the system matches you with an accountability buddy who will also work during that time. You work w/ video chat on. MultiTimer: A variety of incredibly configurable timers Focus ToDo: I couldn’t find a timeboxing app I like, so I make do with this. On converting to MIA Japanese Card Type I’ve gotten several messages saying that this process was very unintuitive. Here is a step-by-step guide to taking the core2k deck recommending you use, converting it to the MIA Japanese card type and then using the MIA Japanese Addon to add pitch-accent information to the cards. 1. Download the MIA Japanese addon; here’s its user manual, for reference. 2. Follow the user manual’s instructions to add the addon to Anki. 3. In the top of left-hand corner of your screen, click tools > manage note types. I’m going to make a small adjustment to the MIA Japanese card type to make it easier to keep track of which word I’m learning in a given sentence. If you don’t want to do this, skip to step 11. (OR, if your end result consistently fails [see comments in step 27], see if skipping this section fixes your issue. Skip to step 11, convert the Core 2k to the default MIA Japanese card type. You will follow the same steps, just without “Target Word” field. Page 151 4. In the top right corner, click “add” Page 152 5. Select MIA Japanese, then click “okay”. You’ll be prompted to name it; do as you wish. 6. Select your new note type and then, in the mid-right, click “fields” Page 153 7. Click on “add” 8. We’re going to add a field to more clearly indicate the word you’re learning from each sentence. I’ve named mine “Target Word”, do whatever you want. Page 154 9. Close the “fields for [whatever you named the deck]”, then X out of the “note types” interface. You should now be back at Anki’s home screen. 10. In the toolbar just above the list of your decks, click “browse” 11. A new window will open up that looks like this. On the left hand pane there are several icons; the three stacked cards represent a deck, the horizontal bar graph looking thing below is your note types and under that are all of your tags (not shown in this screenshot). Page 155 12. Wherever it’s located, click on the label for your Core 2k deck. Upon doing so, the previously empty boxes on the right-hand pane will become populated. 13. Click on any random card in the top right field. I’ve clicked on “hitotsu” and you can tell that I’ve done so because it’s highlighted and the text changed to white. Page 156 14. Click “ctrl + a” to select all of the cards in the deck. You’ll know you did it right because in the top-left corner, you’ll see text indicating that all of the cards in the deck have been selected. I’m using a copy of the Core 6k, so yours will look a little different, but you can see that it says “Browse (5999 cards shown; 5999 selected)” in the top-left. Page 157 15. In the top right list of menus, select “notes” > “change note type” 16. There are many more fields in the Core2k card type than the MIA Japanese card type. Not all of them will get transferred. Go through the fields and make the following changes: Change Vocabulary-English to: Target Word* Change Expression to: Expression Change Sentence-English to: Meaning** Change Sentence-Audio to: Audio * By default, the target Japanese word of each sentence has been bolded. Thus, set the translation of the word to Target Word, the field we added. (Edit: The text is right, the image is wrong. I did multiple tests and got stuff mismatched. Set Change Vocabulary-Kanji to: nothing, and set Change Vobulary-English to: Target Word). * Since you’re just beginning, I assume that you’ll need an English translation to understand the sentences. If you don’t want it, set Sentence-English to “nothing” instead. Ensure that no fields are set to “audio on front” -- this turns all the card into a listening comprehension card (nothing displayed on the front, audio played only). Do not scroll; click and drag the side bar. Anki is a bit unintuitive and sometimes scrolling will scroll through the drop down menus, changing the settings you’ve chosen. We’re currently editing every single card in the deck, so be careful. Page 158 When you’re done, click OK. 17. Closing out of the “change note type” window, you’ll see your newly formatted cards. If you scroll through the panel now, you should see that all of your cards only have five fields: target word (the one we made), expression (JP sentence), meaning (EN sentence), audio (MP3 recording) and a blank entry for “audio on back”. (Edit: again, the image/text here are mismatched. Unlike my image, next to “target word” you should see an Engish word). Page 159 18. As in steps 14/15, select a card from the Core 2k deck and then click “ctrl + a” to highlight every card in the deck. Again, you can check the top-left corner of the screen to ensure that all of the cards have been selected. Page 160 19. In the top-left bar of menus, select “file” > “Generate Readings/Accents/Audio” 20. There’s a bit to do here. Set “Origin” to “Expression”. This tells the MIA Japanese Addon what field of your card it should be analyzing. Set “Destination” to “Expression”. This tells the MIA Japanaese Addon where it should store the information it generates. - Check “furigana” if you want to generate kana telling you how to pronounce each kanji-word in a given sentence - Check “dict form” if you’re not very good at conjugating verbs/adjectives. Doing so will generate a dictionary-form verb and place it in brackets behind the conjugated words for your reference. - Check “accents” to color code your Japanese sentences according to their pitch accent - We already have nice audio from the Core 2k, so do not check this. If you happen to be using a dictionary without audio, or making your own deck, I believe this will take a recording from Google Translate. - Check “graphs” to generate an a graph showing what happens to a speaker’s pitch over the Page 161 course of reading a sentence, taken from Suzuki Prosody Tutor (sample graph). This can be useful at first, but Suzuki isn’t perfect and often generates not-quite correct graphs. I personally don’t use this option, but if you do, take it with a major grain of salt and don’t be shocked if what you hear doesn’t seem to match the chart. 21. When your options menu looks like mine (perhaps with furigana also selected) change “overwrite?” to “Overwrite” and then click Execute. - clicking “overwrite” replaces everything in the selected field with the generated information. - Selecting “add” will input a break (go to the next line) and then add the generated information to what already exists in the field. Doing this will leave you with your original sentence, plus a duplicate just below it that displays pitchaccent information. - Selecting “if empty” will not do anything to the field unless it is blank. If it is blank, it will fill it with generated information. All of the cards we’re using have full expression fields, though, so there is no point to selecting this. The addon will ask you for confirmation; select “yes”. 22. The addon will begin generating pitch-accent information and editing your cards so that they reflect this information. Depending on how big your deck is, this may take some time. Page 162 23. The front of your card will appear normal at first glance. As you can see, the word we’re learning is bolded, but other than that, it’s just a plain card. (minus the fact that I goofed and duplicated everything by clicking “add” instead of “overwrite”). 24. Mousing over a word (desktop) or tapping it (mobile) will display the color associated with its pitch accent and show a popup diagram. Page 163 25. Clicking on “show answer” will flip the card over, fully highlighting each word in the sentence to display their pitch accents. JP audio will autoplay upon flipping the card. 26. Unfortunately, the addon isn’t always the most reliable. If instead of seeing nice and clean sentences like the above, you instead see an all black sentence with stuff like [;h0] in brackets, something went wrong. Delete the deck from your Anki, reimport it and try one more time. If it still doesn’t work, try starting from step 10 instead (use the original MIA Japanese card type format, don’t add an additional field). 27. The MIA Japanese Addon is super useful, but it isn’t perfect. In some cases I’ve found that it leaves a field blank instead of populating it with information, and it occasionally generates incorrect pitch accents. Normal words are ok, but it seems to struggle to parse words that include numbers (such as months and some counters). For example, 四回目 below is treated as being multiple separate words, when it should be one word with the heiban pitch accent. Page 164 You can fix this by clicking “edit” in the bottom-left hand corner of the screen and manually correcting the pitch accent. In this case, delete the first two sets of highlighted brackets [;a] and [;a]. Then replace it with the correct pitch accent. Unfortunately, bolded text seems to interfere with the word parsing, so you’ll have to unbold the entirety of 四回目. Page 165 Anecdotes and Reflections I’m not a linguist and I probably won’t cite anything, but if you’ve stuck around for this long, perhaps you’d be interested in hearing how I look at some more meta-learning topics. These topics have influenced this document, but I didn’t feel that they were directly relevant to the concrete thing you were working on at the time. Objectification, or why it’s hard to find good language exchange partners The problem with language partners (literally do anything else / this series of posts) Page 166 I’m Fed Up: Translate situations, not words ie; you aren’t concerned with how to literally say I’m surprised to say… you’re just concerned with how Japanese people preface another statement to indicate that they’re surprised. And then when that situation comes up, you drop in your functional statement. Sudoku and Zones of Proximal Development [copy/paste… excerpt from this post of mine, will tidy up later] //on immersion, before achieving a foundation ● ● ● A few days ago, there was (apparently) someone who had complained that they still had a low level of Japanese despite having spent thousands of hours watching anime/drama/etc Another person responded to that saying if you study a lot, but are still at a low level, chances are what you're doing isn't really studying Another person responded to that, saying immersion is all you need I think that all of these people have something valuable to say. I agree with both responses. I think that what is being missed is that learning isn't an either:or thing. You need immersion and study. In educational theory, there is an idea called the zone of proximal development. 1. There is some stuff that you can do all by yourself 2. There is some stuff that you could do with the help of a teacher/resource, but not by by yourself 3. There is some stuff that you could not do even with the help of a teacher/resource To put that into perspective, I'd like to ask you to skim through this video of a guy solving a sudoku puzzle. Let's think about those zones in terms of numbers on the board: 1. He begins with only two numbers; this is " i " 2. Those two numbers enable him to solve certain squares; those squares are " i + 1 " 3. The rest of the squares are "i + (more than one)". Given his current situation, he cannot solve the squares. 4. Once he solves the squares in step 2, everything changes. The squares that were previously i+2 become i+1. Basically, depending on where you are in the puzzle, certain squares are and aren't solvable. ● A person who hasn't solved any squares could spend weeks doing serious math trying to figure out the i+2 squares, but not get anywhere. For this learner, those squares aren't worth much. Page 167 ● For a person who has solved the first batch of squares, focusing on those squares that were previously i+2 (but are now i+1) enable them to make progress in the puzzle and eventually solve it IMO learning works in the same way. Theoretically speaking, I suppose it's possible that we could i+1 our way to proficiency. But this isn't an ideal world, and we have a few issues: ● ● ● We're not linguistics and probably can't accurately assess our "current level" Even if we could accurately assess our "current level", non-linguistic factors might prevent us from realizing that what seems to be an i+1 piece of content/sentence is actually i+(more than one) Even if we could accurately assess our current level and perfectly identify content as being i+1 or not... the technology doesn't exist to create a personalized sequence of i+1, 2, 3... content. We have to go digging through content and "mining" for ourselves in order to find the content that's actually i+1. When we're a total beginner, the content that's truly i+1 is very limited. Taking the time to work through Genki or something like that gives you a foundation that basically gives you leeway. The perimeter of a 1x1 square is 4, of a 2x2 square is 8... etc. If we can build an even slightly bigger square, we expand the range of content that could potentially sit at its perimeter, being i+1. It's not that you have to do this, it's just that spending the time to build a foundation makes it more likely that you'll succeed with a given piece of content. The bigger base you have, the more likely you are to be able to latch onto and learn something. Eventually your square of knowledge gets so big that you can learn from practically anything even without explicit effort. Learning (Multiple) Languages: Something Has to Give Something has to give / making time in a full life (maybe should go in intro)? English as a Supervisor: learning to think in Japanese On learning to think in Japanese / not translate from English (include this?) - English as a “supervisor” -- we don’t need to think about konnichiwa, but when we stumble into something we’re not comfortable with, English steps in and we try to figure it out. To start with, stick with simple manners of speech that you’re more comfortable with. - If you can output directly from Japanese, it means that the Japanese word or phrase holds enough inherent meaning to you as to be nearly tangible. Whenever you see a desk, it proudly stands up, puffs out its chest and proclaims that it is a tsukue. You won’t have that kind of connection just because you made a flashcard that says desk:tsukue. Continue getting input, give the words/language a change to sink in, and it’ll come eventually. Page 168 - English isn’t the world, it’s sort of like a thin veil that’s been sitting on top of the world for so long that we’ve forgotten about it. Or maybe it’s better to say that our inner world is an ocean, and English is a river leading from that ocean. Learn to think about the ideas you want to express rather than the words you’d use to express that idea; draw from the ocean, not the river. - Unfortunately, we don’t perceive objectively. We selectively ignore many things, so when we first begin, it can be difficult to understand what exactly we’re trying to say. Here are a few examples: - Take a piece of paper and hold it in front of your mouth. Say the word pit aloud -- the paper will billow up a bit. Now say the word spit. It should billow much less, if at all. Why? The P in spit and pit is not the same; spit has an unapirated P, pit has an aspirated one. Most English speakers don’t recognize they’re different sounds because we don’t distinguish them, but for a Korean speaker, these sounds are as different as B and P. - Just as with sounds, some languages pile a lot of different meanings onto a single structure. Take is ~ing -- the meaning of this structure changes depending on what type of verb we’re dealing with. - He is falling (he only falls once, and we’re observing him in the process of falling) - He is blinking (he blinks several times in quick succession) - He is wearing clothes (he has put clothes on and remains in the state of having clothes on) - Perhaps you’re smarter than I am; the point I want to make is simply that we probably aren’t aware of what all we’re actually communicating when we say something in English. Unfortunately, to speak Japanese, it’s necessary to understand what we’re trying to say and to choose the corresponding grammar structures. You’ll get better as you go, but again, this takes time. Administrative stuff, for lack of a better word Thread w/ many free resources Links that I probably want to use somewhere Basic pitch accent info Fluent-Forever’s intro to Italki Page 169 NINJAL-LWP Japanese Corpus → super useful resource. Input any verb, see (a) which conjugations are more common and (b) what words it most often gets paired with NINJAL Compound Verb Database → similar to the above but specifically for compound verbs (two verbs stuck together); each vocab word includes a few example sentences and there’s also a nice overview of some basic syntacic elements of JP verbs Kanji How kanji work | Tofugu Kanji stroke order | Tofugu On looking words up The 217 kanji radicals Grammar Verb conjugation How particles work Cool verb conjugation chart Visual grammar explanations Lots of grammar points, explained in clear Japanese | Similar site (outline, examples, body) | II Learning plan by JLPT level Marshallyin Grammar explanations Edewakaru YouTube walkthrough of Genki Intro to Japanese -- [quite technical] online grammar textbook Did I mention flippantry? Just in case Anime/games/manga by readability (+resource dump) by jo_mako Lots of free resources Free online Japanese course from Kyoto University Genki Companion Website | Genki (Companion?) Videos | Guy presenting Genki JapaneseComplete guide product behind it, but very simple/accessible intro to grammar topics Concise notes about Genki grammar points A super detailed verb conjugation cheatsheet (and one more basic one) Anki the intermediate plateau (part II) Anime/Drama flashcards (... use with morphman) JLPT Sensei turned into N5/N4/N3 Anki grammar deck Site type stuff The original ajatt - might be some useful stuff Tons of FAQs about learning Japanese Useful resources dump Page 170 Other/general learning The basic structure of a story The importance of familiarity, buildup and expectations (also this) Top 10 breakthroughs in the science of learning How to make a behavior addictive the like switch Constructive practice and effortless practice Podcasts Voices in Japan - what everyday life in Japanese is really like Voices in Japanese Studies - longform discussions with people studying Japan and Japanese professionally. Could be a nice start if you’re thinking about majoring in Japanese. colorful words / slang (idk where to put this) Learners given task… they became more efficient while practicing, and by the end of the task, it took 20% less metabolic power to perform the task. As you master simpler skills, you remove energy-constraints from your brain in a very literal sense that allows you to spend more energy focusing on the important/difficult parts of your tasks at hand. You can perform better at someone, even if you don’t know anything more than they do, sheerly because your body works more efficiently. The Dip by Seth Godin - the extraordinary benefits of knowing when to quit. When you first begin anything, there’s a burst of excitement and everything is new/novel. Remembering new stuff is easy. Quickly, all this stuff starts to build on each other and we realize how much there is to learn -- the first wall. Most people quit at this wall. This book is about how to get over it. Edward Thorndike & The Start of Educational Psychology → Quantity eventually becomes quality → While cats had a clear “success” signal (they could finally get out of the damn box), you Probably don’t. How can you change that? (TL;DR) Not 6 degrees of separation, but 3.5 (II) What I’ve learned working in PR and spending a year exploring freelance writing -- we’re pretty closely connected. It’s not really that hard to get in touch with people… but most people don’t. As this is the only thing I have data about -- there are currently 60 concurrent non-idle readers of this document; that number has slowly increased from 30 since I shared it. It’s got ~2.5k upvotes total. I’ve received 9 pieces of feedback on the survey; I’ve Page 171 incorporated much of it. Perhaps 20 people have sent in small questions/clarifications. Two people have had extended (over a couple weeks) conversation with me. On the Fluentin3months website, Benny Lewis at one point commented that practically all the people working for him were people who just reached out -- hey, I noticed your site doesn’t have [thing]. I do [thing]. Here’s how it can help. Would you be game to Skype for half an hour and talk about it? Well, only one person has offered to pitch in: he offered to help turn this into a website. If I was interested in expanding, he’d have a job (or at least, a shot) -- and all he did was ask. So far I’ve written for or worked with five language companies, some small and some large In all of these cases, again, all I did was ask. Sometimes it was just an email with writing samples, other times I put together a presentation with some SEO data and offered suggestions to improve their blogs. Oftentimes I was able to connect with people well enough to keep in touch with them even if it didn’t turn into a job. So, if you want to do something, reach out. Very few people do. Page 172 Changelog - - - - - 04/29: began chatting with /a company/ about shooting a small video for one of their series. Still in the works (have to get my talking points verified), but it’s officially in the works. I’ll do five 2 minute segments, one in EN/SP/JP/RU/CN. 05/01: added one page summary to beginning of document, moved old “day zero” content to appendix 05/06: received confirmation to do an interview with the CEO of Satori Reader; nothing set in stone yet, but he’s willing and I think he has a lot to offer ^^ 05/08: added final chapter to the section on vocabulary (on memorizing stuff) but I don’t like it. I’ll re-do it later once things are further along. 05/09: finished draft of mini-chapter based on interview with Matt vs Japan; will be available soon 05/12: added introduction to the input section, currently organizing the chapter. 05/14: added changelog so it’s easier to see what I’ve been up to 05/15: Outlined the input homework: reading section 05/17: I’ve been receiving good feedback about the one-page summary from 05/01, so I’ve expanded upon it a bit. I’ve added three new sections: stages of language acquisition, stage one and a placeholder for stage two. I also re-worked the how to use this document section of the introduction. Hopefully these changes will make it easier to navigate this document. 05/19: Revamped the first two sections of the phonetics section: opening words and TL;DR. 05/26: Revamped the pronunciation chapter’s section on homework. 05/29: Have been thinking about the input section. Added the section opening words and began outlining the start here section. 05/31: I spent the afternoon writing a long-winded and wordy post instead of finishing up Matt vs Japan’s interview. Sorry guys, and thank you Matt for your endless patience. 06/08: Finished the Input section’s opening words, part of its TL;DR and the introduction to the reading section. Next I’ll flesh out the homework sections for reading and listening. 06/15: Finally finished the write-up of the interview with Matt vs Japan. Just waiting to get the green light from him and then it will be added -- 11 pages! (Sorry for the delay -- we’re preparing for a global conference at work and I haven’t had time to write recently). 06/19: Added Speechling as a resource in Pronunciation’s further practice section. 06/22: Fleshed out ~half the section for Input: Reading Homework 06/23: Finished thet Input: Reading Homework section. Might trim/reformat later. 6/27+28: Began putting together a ~15 minute video showing me speaking my languages. English overview, then ~3 minutes elaborating on an idea from that overview in SP/JP/RU/CN. My first take was ~40 minutes long and mostly just rambling… I decided that nobody really wants to see another person just speaking languages, so I’ve tried to condense it down into something actually helpful. Also, there’s so much I didn’t know about presentation/making video content. I gained a ton of respect for YouTubers this weekend. 06/29: Added in a few “stage 12” starter’s reading suggestions after someone’s feedback (thanks!) -- also began fleshing out the listening comprehension section. Page 173 - - - - - - 06/30: Added Matt vs Japan’s interview! 07/01: Made minor adjustments to the phonetics - vowels, revolving around this excellent lecture I found. Recently I recorded myself speaking for the first (see 6/27 entry) and it was an incredibly enlightening experience -- I encourage everyone to record and listen to themselves! I really learned a lot. Based on stuff I realized I was doing wrong (and am thus now learning about) I’d like to expand the section with one more section that covers phonetics in a bit more detail, and I might revamp the pitch accent section a bit to more clearly contrast stress/pitch accent. That’s for later, though. 07/02: Began the output section. There’s a lot of stuff that I’d like to talk about it, so I’m still working out how I’d like to go about organizing everything. 07/04: Added a section to the appendix documenting how to set up the Core 2K for use with the MIA Japanese Addon for pitch accent. 07/07: After deciding what I wanted to say, trimming down from a 40 minute to 15 minute script, taking a crash course in camera angles/filming do’s and don’ts (I use my hands a lot…) I’ve now finished recording my video. It’s off to be edited. I’ve said it before, but it was a really interesting experience. I think I want to add a new segment to each section documenting my personal failures (similar to the what I actually did bit of the kanji section) so that you all can hopefully learn from my mistakes. 07/10: Planning to get back to the output section next week and my goal is to finish it this month. The last couple weeks were really busy; I’m going to take a break from this to work on a short story. 07/13: Added a section to the appendix that walks through my learning schedule. Expanded the “closing words” page of the introductory section. 07/14: Added The Golden Circle by Simon Sinek to the appendix on learning 07/18: Had the interview with Brian Rak of Satori Reader! Super excited to be putting it together, even though I wasn’t smart enough to do the time-zone conversion by myself and ended up waking up at 5:30 on a Saturday morning… I think it was worth it, hope you will, too. 07/21: Small update today; revised the stages of language acquisition page to better emphasise the recursive nature of my perceived stages two and three. 07/22: Put together a quick “start here” TL;DR page for the output section 07/23: For the last few days Google has been prompting me to publish the document due to heavy traffic for a live document… so I went ahead and published it via Google. The formatting isn’t that great, unfortunately, but it should be more stable than this version in the event that you keep getting kicked off or something like that. 07/27: Have been slowly learning about drawing and stumbled onto a video I really liked that outlines the learning process in an accessible fashion. Included in initial start here. 07/30: The count of concurrent viewers has been gradually increasing over time, but today when I opened the document to add a podcast to the list I saw that it was at 100 concurrent viewers (including me), which I believe is the maximum amount that Google allows at once. That’s a really cool milestone, but I hadn’t expected so many people to be interested in this and I’m not sure what to do if we outgrow the Google Doc. I’m not very tech-friendly ;;^^ Page 174 - - - - 2021 - 08/10: Took a longer break on a writing kick than I expected. Am currently putting together the article based on Brian’s interview from 07/18. I’m hoping to get it finished, reviewed by him and up within the next week or so. 08/11: Getting several complaints about explanations of using Anki. I’m a pretty typical / vanilla user, but for the time being, I’ve added a link to the vocabulary section of the document that leads to the appendix section I added on setting up MIA Japanese for use with the Core 2k. 08/13: Just wanted to clarify that I haven’t been making updates to this document because I’ve been working on Brian’s interview in another document. Big-ish update soon :) 08/18: I’ve now finished writing out Brian’s interview (coming soon!) and the short story I took a detour to write. So, finally, I’m turning my attention back to the output section. 08/19: Added an appendix entry in which I talk about meditation. 08/25: Brian Rak’s interview about making a career out of Japanese has been finalized, approved and is up! 08/28: Finally returned to the output section. Added the section entitled mouthwork. 09/03: Added the entry entitled scripting to the output section 09/04: Added the entry entitled early conversations to the output section 09/21: Have been absent for quite a bit lately, my apologies. It’s the busiest time of the year for me at work and I’ve been revising something written by a friend. Will hopefully get around to the last two output sections soon, then I’ll put together a few small essays I’ve been planning for awhile. I’m excited to be reaching a point where I can write whatever I want, rather than just working on the next section. Once I’m done with those I’ll move onto V2, starting with the pronunciation resource dumb and revising the kana section. 09/24: Put together the first half of the output:conversation section 10/11: I’ve finished V1 of the document after just about a year. Cool beans, cool beans. 10/20: I’ve began V2 and began revamping the kana section. Added opening words. 11/12: That was a longer break; I needed some time away after a work project ended and have been working on a short story. Today I made some revisions to the pronunciation chapter and began re-organizing the kana chapter. 11/25: Today I revamped the initial start here blurb to be more actionable 01/21: Finished pronunciation & kana revamp To Do List (based on feedback) - 5/31: Maybe something to think about- instead of organizing by section (grammar, vocab, kanji, pronunciation) you organize by skill level: what beginners/intermediate/advanced should be doing in each “stage”. What resources are suited for which levels. → I agree that this sort of organization would probably make more sense than what I have. For the time being, I’d like to finish the main body of the document so that the foundation is there. Once it’s Page 175 - - - - done, I’ll create a beginner’s landing page and an intermediate one. This will link to relevant pages of the document, providing a more clear overview of what I expect you to be doing at a given time, rather than making you read through each chapter simultaneously. The main bit of advice I’ve garnered from your feedback (thanks!) is that my original post was useful because it was concise, packed with resources and actionable. In this document I’ve greatly expanded, resources are more spread out and it’s more of a discussion, rather than a series of commands. While these changes are useful for people who are committed already, it makes this document significantly less accessible for. → I’m in the process of re-structuring the document to be easier to follow. See my plans on the page on “how to use this document”. Include a resource dump somewhere that TL;DR’s resources by section, including some stuff that didn’t fit into what I originally wrote, like Rikaisama/an IME → As I’ve outlined in “how to use this document”, I will (V2) add a resource-dump page to the end of each chapter. Include a few online dictionary (J>E and J>J), links to videos showing how each sound in Japanese is made and add an appendix on keigo. → For the time being, I recommend that you look up which sounds are in Japanese via the Japanese IPA wiki and then copy and paste the symbols into a YouTube search for content by Glossika Phonetics. For example, -- [ɸ] glossika phonetics -- brings you to this video on how to make the Japanese F sound. You will need to go through Artifexian’s videos on the IPA system that I linked to in the phonetics section to understand these videos. 6/29: Quite a few people have left feedback requesting extensions of the guide to cover more advanced topics/through the N1/etc. When I otherwise complete this document I might add some of that, but I want to emphasize that my main goal here is to help beginners reach a point of independence in which they feel comfortable figuring that out for themselves. If anything, I could see myself expanding the grammar section to introduce more resources/options, expand the input section with reading suggestions for getting into different genres, and stuff like getting the most value out of your time reading. There is just so much content you could cover in the advanced stage that it just isn’t really practical to cover… what you learn at an advanced stage largely depends on you and your unique needs. For example, I have a 150 page reference book that discusses only Japanese emails. It walks through the structure of Japanese emails, in depth looks into several different types of emails for different purposes, reaching out to different types of people/businesses depending on your status (consumer, competitor, worker, boss, colleague, etc).... Useful for me, and necessary for my “advanced”, as I will be helping to coordinate a major event with the Japanese branch of my company next year, but I really doubt that this sort of thing would be useful for most people. Thanks A lot of this document isn’t just me; it’s composed of several hundred links directing to content that has been created or organized by other people. But, in particular: Page 176 - A huge thanks to Virusnzz, the moderator at r/LanguageLearning, for his invaluable feedback. A huge thanks to all of the busy content creators who took time out of their day to meet with me for a bit A huge thanks to the nine of you (so far) that have left me feedback; I’ve incorporated many of your suggestions while making revisions to the document. A huge thanks to you, for putting up with my writing. Leave Me Feedback I’m not interested in your money, but if you could spare me a few minutes of your time, I would appreciate your feedback. This is the longest piece of writing I’ve shared publicly, and if I’ve learned anything from writing circles, it’s that everything needs revision and a second draft. Based on feedback so far, I’d appreciate if you’d let me know how I’m doing in terms of: ● Approachability. Language has been a huge part of my life for the last 5 years, so sometimes it can be difficult to step back and think about what a beginner needs. Do you feel like my document is accessible, or do you feel like you’re being thrown into the deep end? ● Organization. Overwhelmingly, the feedback I’ve gotten says this is great, but… followed by a comment about how there’s a lot of content, people aren’t sure where to start and that I could have presented my thoughts more clearly. I’ve been trying to address that by re-working the structure of the document. How am I doing? If you’re willing to leave me feedback, or you’d like to request that I cover certain topics, you can do so here. ( 9 questions, all optional, no login required ) Potentially useful threads / links I may work these into the document’s main body at some point .... but until then - Japanese tense and aspect: する・した|している・していた (その2)| Page 177 Page 178