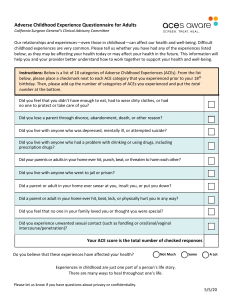

Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Child Abuse & Neglect journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chiabuneg Research article Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and adult attachment interview (AAI) in a non-clinical population MARK ⁎ Paula Thomson , S. Victoria Jaque California State University, Northridge, United States AR TI CLE I NF O AB S T R A CT Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences Adult attachment interview Disclosure Trauma Unresolved Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) tend to be interrelated rather than independently occurring. There is a graded effect associated with ACE exposure and pathology, with an increase when ACE exposure is four or more. This study examined a sample of active individuals (n = 129) to determine distribution patterns and relationships between ACEs, attachment classification, unresolved mourning (U), and disclosure difficulty. The results of this study demonstrated a strong relationship between increased ACEs and greater unresolved mourning. Specifically, the group differences for individuals who experienced no ACE (n = 42, 33%), those with 1–3 ACEs (n = 48, 37.8%), and those with ≥4 ACEs (n = 37, 29.1%) revealed a pattern in which increased group ACE exposure was associated with greater lack of resolution for past trauma/loss experiences, more adult traumatic events, and more difficulty disclosing past trauma. Despite ≥4 ACEs, 51.4% of highly exposed individuals were classified as secure in the Adult Attachment Interview. Resilience in this group may be related to a combination of attachment security, college education, and engagement in meaningful activities. Likewise, adversity may actually encourage the cultivation of more social support, goal efficacy, and planning behaviors; factors that augment resilience to adversity. 1. Introduction 1.1. Adverse childhood experiences Exposure to childhood adversity has a graded effect associated with an increase in pathology when adverse childhood experiences (ACE) involve four or more exposure types (Felitti et al., 1998). Worldwide, childhood adversity accounts for 29.8% of all disorders across all life stages (Kessler et al., 2010); family dysfunction and child maltreatment are strongly related to physical/psychological suffering and to substantial health care costs (Felitti & Anda, 2010). Likewise, early attachment experiences shape internal working models that inform behavior throughout the lifespan (Bowlby, 1988 Hesse & Main, 2000). Currently, there is insufficient research that addresses the distribution patterns of ACEs and attachment classifications in a community sample. This study attempts to explore childhood adversity and resilience in a college-educated sample that actively engages in ongoing meaningful activities. The researchers hypothesized that despite childhood adversity, a greater proportion of individuals in this sample would be able to discuss past attachment, loss and trauma experiences, while maintaining coherence and a sense of autonomy. One of the major factors when examining childhood adversity is the reality that ACEs seldom occur in an isolated form. For example, children who are sexually abused are more likely to experience other forms of abuse and neglect (emotional and physical) ⁎ Corresponding author at: California State University, Northridge, 18111 Nordhoff St., Northridge, CA, 91330-8287, United States. E-mail address: paula.thomson@csun.edu (P. Thomson). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.001 Received 26 February 2017; Received in revised form 14 May 2017; Accepted 1 June 2017 Available online 19 June 2017 0145-2134/ © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque and be raised in a family that is dysfunctional (domestic violence, addiction, mental illness, separation/divorce, incarceration) (Dong, Anda, Dube, Giles, & Felitti, 2003). ACEs tend to be interrelated rather than independently occurring; the presence of one ACE often leads to increased risk for more ACEs (Dong et al., 2004). With increased ACEs comes an associated risk for increased morbidity and mortality, including heart disease, metabolic disorders, psychopathology (depression, suicide, addiction), and sexually transmitted diseases (Felitti et al., 1998; Felitti & Anda, 2010). 1.2. Attachment theory Positive early attachment experiences, especially when parental care is sensitive and supportive, protect children from exposure to the negative consequences of adversity. Typically, negative attachment experiences are strongly associated with insecure attachment classifications and later psychopathology (Hesse & Main, 2000; Wright, Crawford, & Del Castillo, 2009); and childhood abuse and neglect are strongly associated with insecure attachment (Raby, Labella, Martin, Carlson, & Roisman, 2017). Early attachment experiences shape internal working models (IWM); they determine whether individuals actively seek solutions during distressing events, withdraw and minimize the experiences, or amplify emotional responses (Main, 2000). For example, when recalling emotional attachment-related memories from childhood, individuals may exert efforts to deactivate and reduce these memories (dismissing) or hyper-activate their intensity (preoccupied) (Dykas, Woodhouse, Jones, & Cassidy, 2014). A preoccupied state of mind actually intensifies negative moods and increases psychological problems (Creasey, 2002). When both dismissing and preoccupied strategies are co-activated individuals are considered globally disorganized; they lack a single consistent strategy to manage attachment-relevant memories. The powerful influence of attachment experiences, both positive and negative, are internalized into models of self, other, and the world (Main, 2000; Hesse & Main, 2000; Main, Goldwyn, & Hesse, 2003; Weinfield,Whaley, & Egeland, 2004). By analyzing adult narrative discourse, early attachment IWMs stored at implicit unconscious levels, emerge during discourse (Main et al., 2003). For instance, the effects of previous traumatic experiences, including childhood adversity, are identified in narrative analyses. In general, trauma narratives expose sensorial/perceptual and emotional detail of the event; they also shed light on how the speaker is managing the event psychologically (Crespo & Fernandez-Lansac, 2015). The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) can measure the degree of psychological resolution for significant trauma and loss experiences. It evaluates the nature of the speaker’s discourse and reasoning. When a speaker’s state of mind is deemed unresolved, significant lapses in monitoring appear in the narrative. Narrative lapses include (1) disorientation to space and time, (2) psychologically confused speech (manipulating the mind to obscure unwanted memories), (3) confusion and disbelief about abuse or death, (4) extreme absorption (excessive detail, shift to eulogistic or poetic language), (5) prolonged silences (greater than twenty seconds), (6) unfinished sentences, (7) sudden changes of topic, (8) intrusions of frightening images, (9) sudden changes in speech patterns that are more appropriate to much younger speakers, or (10) intrusion of memories of loss or trauma that randomly appear throughout the interview (Hesse, 2008; Main et al., 2003). These lapses of monitoring are evaluated on a continuous nine-point scale (Main et al., 2003), and a score of 5 or greater places an individual into a primary unresolved state of mind (U) classification (Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn, 2009; Hesse, 2008; Main et al., 2003). The encapsulated lapses of monitoring suggest that the speaker is still unable to organize and articulate past trauma/loss experiences. A strong relationship exists between an unresolved state of mind regarding past trauma/loss experiences and increased childhood adversity, especially in clinical samples (Murphy et al., 2014). In the Murphy et al. study, 84% of the clinical sample had 4 or more adverse childhood experiences (ACE) compared to 27% in the community sample. A similar pattern was found for those classified as unresolved (U) or globally disorganized (CC), with 76% of the clinical sample classified as U/CC compared to 9% of the community sample. As expected 65% of the U/CC group also had 4 or more ACEs. These findings reinforce previous studies demonstrating the graded effect of ACE exposure (Felitti et al., 1998), and the link with unresolved mourning (Murphy et al., 2014). 1.3. Disclosure difficulties and resilience Difficulty disclosing past traumatic events is also associated with increased psychopathology (Ullman, 2007). Fear of negative reactions to disclosure may increase a failure to disclose, although a delay of disclosure is relatively common in victims of childhood sexual abuse, especially when the perpetrator is a family member (Smith et al., 2000). In a non-clinical sample, when a traumatic event is deemed too difficult to discuss, PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms are usually elevated (Vrana & Lauterbach, 1994). Enhancing disclosure rates, a factor that influences trauma recovery, is fundamentally predicated on identifying barriers to disclosure and fostering a supportive climate to reveal traumatic incidents (Ullman, Foynes, & Tang, 2010). Despite strong evidence supporting the deleterious effects of childhood adversity, unresolved states of mind, and disclosure difficulties, there are many individuals who are exposed to adversity and yet remain resilient; they have good psychological outcomes despite adversity (Bonanno, 2004; Rutter, 2006). McGloin and Widom (2001), report that 22% of abused and neglected individuals are deemed resilient. Rather than focusing on the deficits associated with childhood adversity, resilience may be an ordinary component of human development (Masten, 2001). According to Rutter (2006), factors that may contribute to resilience include controlled exposure to adversity and optimal biological or neurological responses to stress. Another resilience factor is engaging in meaningful activities, in part because these activities promote connectedness, a sense of belonging, enhanced self-efficacy, and positive coping strategies under stress (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Masten & Obradovic, 2006; Oliver, Collin, Burns, & Nicholas, 2006; Walsh, Blaustein, Knight, Spinazzola, & van der Kolk, 2007). Attachment security in children and adults is also associated with increased resilience (Bailey, Tarabulsy, Moran, Pederson, & Bento, 2017). Even with an unresolved classification, a secondary secure/ 256 Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque autonomous classification may operate as a protective variable to adversity (Thomson & Jaque, 2012). Also, adults who report only low-loving instrumental care as children can “earn” attachment security later via receiving emotional support from alternative supportive figures during childhood or adulthood (Main et al., 2003; Rutter, 2006; Saunders, Jacobvitz, Zaccagnino, Beverung, & Hazen, 2011). College education and intelligence also buffer the negative effects of childhood maltreatment (Oliver et al., 2006). All of these factors can potentiate resilience (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Masten, 2001; Walsh et al., 2007). The goal of this investigation was to examine the relationship between ACEs, attachment classification, and ability to disclose past trauma in a sample of well-educated individuals who self-acknowledged regular participation in meaningful activities. The study investigated whether more ACEs were associated with increased prevalence of unresolved mourning, cumulative trauma, and an inability to disclose past abuse. By addressing this question, resilience prevalence is implied; it is hypothesized that despite ≥4 ACEs, a substantial proportion of individuals in this sample will not be classified as unresolved with respect to past trauma and/or loss (Collishaw et al., 2007). 2. Methods 2.1. Participants In this Institutional Review Board approved study, a sample of participants (n = 129) was randomly selected from a larger group of participants who entered a psychophysiological study investigating stress. Given the time and cost demands associated with administering the Adult Attachment Interview, a smaller sample was deemed appropriate (n = 129). Investigating attachment states of mind provided a fine-grained analysis related to attachment classification and degree of resolution for past trauma and loss experiences. All completed the informed consent process before formally entering the study. Participants were recruited from three international cities: Toronto (Canada, n = 26), Cape Town (South Africa, n = 8), and Los Angeles (United States, n = 95). The decision to gather data from these three countries was partially informed by the desire to understand attachment patterns within a group of individuals who managed to acquire college education and pursue activities that were deemed personally important and meaningful. It was believed that the opportunity to interview individuals from three different cities and countries would expand the generalizability of the results. There were no gender or ethnicity exclusionary criteria in this study. The mean age was 27.36 (sd = 9.96) (minimum 18 years and maximum 64 years). All participants were college educated or currently pursuing college education. The inclusionary criteria were met by all participants: (1) no medical (psychological or physical) condition that would reduce activity, (2) currently engaged in a recreational or career activity that was self-identified as important and meaningful. In this sample, 127 participants reported at least one significant loss (19 were considered unresolved for loss). Based on the AAI abuse criteria, 39 participants experienced trauma (18 were classified as unresolved for abuse), and for other trauma (i.e., rape, abuse by another family member) 49 individuals were exposed to other trauma, with 11 who were classified as unresolved. In the full sample 24 participants had received past therapy but were no longer in treatment. See Table 1 for demographic distribution statistics. Table 1 Demographic and variable percentage distributions (n = 129). Variable Gender Ethnicity AAI 2-way AAI 4-way ACE Tell/No Tell N % Male Female African American Asian Caucasian Latino Missing Data Secure Insecure 50 79 17 12 90 7 3 79 50 38.80% 61.20% 13.20% 9.30% 69.80% 5.40% 2.30% 61.20% 38.80% Dismissing (Ds) Preoccupied (E) Secure/Autonomous(F) Unresolved (U/CC) U/F-alt 15 2 79 30 17 11.60% 3.90% 61.20% 23.30% 58.60% No ACE 1–3 ACEs ≥4 ACEs Tell Unable to Tell 42 48 37 105 11 33.10% 37.80% 29.10% 90.50% 9.50% Meta-Analyses 16% 9% 56% 18% Murphy et al., 2014 Study 9% 18% 65% 9% Dube et al. 2003 31.30% 57.80% 26.50% Murphy et al., 2014 Study 20.60% 52.90% 26.50% Abbreviations: ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences; U/F-alt = Unresolved classification with autonomous (F) classification as second alternative classification; Meta-analyses results from Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn (2009) study. 257 Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque 2.2. Measurements 2.2.1. Adult attachment interview (AAI) The AAI is a semi-structured twenty-question interview that is transcribed verbatim. Reliable coders, certified by Dr. Mary Main and Dr. Erik Hesse, assess states of mind regarding childhood attachment, trauma, and loss experiences. There are fourteen dimensional 9-point scales: five inferred childhood experiences with parental figures (loving, rejecting, involving/role reversing, pressure to achieve, neglect), and nine states of mind (metacognition, idealizing, derogation, preoccupied anger, lack of memory, passivity of speech, fear of loss, abuse/trauma experiences, and losses of significant loved ones). Two global dimensional scales evaluate the coherence of the transcript and the coherence of the speaker’s mind (Hesse, 2008; Hesse and Main, 2000Main et al., 2003). Based on dimensional scale scores, the interview is categorically classified in a two-way distribution (secure or insecure), a three-way distribution (dismissing, preoccupied, or autonomous/secure), and a four-way distribution (dismissing, preoccupied, autonomous/secure, unresolved) (Main et al., 2003). Multiple studies conducted internationally have confirmed the psychometric properties of the AAI, including test-retest stability, inter-judge agreement, and discriminant validity (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 1993; Hesse, 2008; Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2009). The AAI assessment yields vastly different results than those garnered from self-report measures (Jacobvitz, Curran, & Moller, 2002; Roisman et al., 2007). Three reliable blinded coders (Melissa Mose, Joanne Seltzer, Paula Thomson) involved in this study received training from Sonia Gojman De Milan, June Sroufe, Mary Main and Erik Hesse. Kappa ratings were calculated between two reliable coders (47 transcripts: 36.4%): (1) 2-way classification κ = .910 (95%), p < .001, excellent agreement, (2) 3-way classification κ = .937 (95%), p < .001, excellent agreement (3) 4-way classification κ = .917 (95% CI), p < .001, excellent agreement. The highest score on either the continuous (dimensional) scale for unresolved trauma or loss were listed as the Uall dimensional scale. When scores were ≥5, a dummy code was created to place individuals in groupings of No-U or U. The U groupings were used to determine group differences in this study. For descriptive purposes, earned secure and continuous secure classifications were conducted. Based on the rigorous criterion outlined by Main et al. (2003), the sample was divided into those whose cumulative mother and father inferred loving scores were ≤3 (potential earned secure classification) and those with a cumulative loving score of ≥7 (continuous loving). 2.2.2. Adverse childhood experiences questionnaire (ACE) The ACE questionnaire is a dichotomous 10 item self-report instrument that assesses categories of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunctions (Felitti & Anda, 2010). A total score of yes responses are derived, regardless of frequency or intensity. The abuse category probes for emotional, physical and sexual abuse; the neglect category probes for emotional and physical neglect, and the household dysfunction category includes mother treated violently, substance abuse, parental separation or divorce, household member imprisoned or suffering a mental illness. Item four is provided as a sample from the ACE Questionnaire: “Did you often feel that …No one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special? Or Your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other? Yes/No.” Since calculating the internal consistency of the ACE is inappropriate, a testretest reliability calculation found that the ACE was stable (r = .956, p < .01). This test-retest reliability calculation was conducted by randomly asking 30% of the sample to return to the laboratory six months later to complete a second ACE questionnaire. For descriptive purposes, we examined each ACE item independently, as well as the aggregated sum. This decision was based on previous studies that demonstrated different psychological effects related to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction (Kessler & Bieschke, 1999; Wright et al., 2009), as well as the cumulative effects (Felitti et al., 1998). 2.2.3. Traumatic events questionnaire (TEQ) A self-report 11 item dichotomously scored measurement (Lauterbach & Vrana, 2001; Vrana & Lauterbach, 1994) assesses exposure to 9 different traumatic events (accidents, natural disasters, crime, child abuse, rape, adult abusive experiences, witnessing death/mutilation of someone, being in a dangerous/life-threatening situation, and receiving news of an unexpected death of a loved one). The final two items probe for any other traumatic event not listed, and for traumatic event(s) that are too difficult to discuss with anyone. The last item was used to divide the sample into ability or inability to disclose. This facilitated an investigation into group disclosure differences related to ACE prevalence, and attachment classification. Since calculating the internal consistency of the TEQ is inappropriate, a test-retest reliability calculation found that the TEQ was highly stable (r = .82, p < .01). The same protocol adopted for the ACE test-retest calculation was followed for the TEQ. 2.3. Research design and analyses SPSS 23 was employed for all statistical calculations. First, kappa ratings were calculated for the AAI categorical classifications. For descriptive purposes, percentages were then calculated to determine pattern distributions for the two-way AAI classification, four-way AAI classification, U classification with a secure (F = autonomous) secondary classification, all adverse childhood experience items, ability to disclose past trauma, and three groupings of ACE (0 ACE, 1–3 ACEs, and ≥4 ACEs). These calculations were conducted on the full sample, the Unresolved (U) and No-Unresolved (No-U) groupings (≥5 on Uall), the three ACE groupings, and ability/inability to speak about trauma groupings. For descriptive purposes, “earned-secure and continuous-secure participants and their profiles were analyzed. See Tables 1 and 2 for distribution patterns. A series of multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVA) (gender and age were covariates) to determine group differences in unresolved mourning, ability to disclose, and ACEs were then conducted. An AAI Security Index (Main, personal communication, 258 Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque Table 2 ACE Groups and Prevalence (Percentage) for 2-Way AAI, 4-Way AAI, and Tell/Cannot Tell Groups. 0 ACE n = 42 (33.1%) 1-3 ACE n = 48 (37.8%) ≥ 4 ACE n = 37 (29.1%) Secure Insecure 31 (73.8) 11 (26.2) 28 (58.3) 20 (41.7) 19 (51.4) 18 (48.6) Dismissing Preoccupied Autonomous Unresolved U/F-alt 6 (14.3) 2 (4.8) 31 (73.8) 3 (7.1) 2 (66.7) 6 (12.5) 2 (4.2) 28 (58.3) 12 (25.0) 7 (63.6) 2 (5.4) 1 (2.7) 19 (51.4) 15 (40.5) 8 (53.3) Can Tell Cannot Tell 36 (94.7) 2 (5.3) 40 (93) 3 (7) 27 (81.8) 6 (18.2) Category 2-Way AAI 4-Way AAI Abbreviations: ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences; U/F-alt = Unresolved with autonomous (F) as the secondary alternative classification. August, 2006) was included in the ACE group MANCOVA calculation. This index provides a dimensional scale for the AAI classifications (5 = F3; 4 = F1, F2, F4, F5; 3 = E2, Ds3; 2 = E1, Ds1, Ds2; 1 = U, CC, E3). For descriptive purposes, MANCOVA was conducted to determine potential geographical differences in the sample. To remedy non-normal distributions, a square root transformation to normalize the variables was calculated, followed by parametric inferential statistical analyses. In the MANCOVA analyses, Bonferroni alpha (.05) corrections were used to counteract the nature of multiple comparisons. 3. Results 3.1. Descriptive statistics See Table 1 for demographic and variable percentage distributions (n = 129). The full sample AAI 4-way distribution patterns differed from the AAI four-way distribution reported in the meta-analysis conducted by Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn (2009) and the Murphy et al. (2014) studies. The three ACE grouping distributions were slightly different than the community sample found in the Murphy et al. study (2014). The 9.5% distribution of individuals who were unable to disclose a traumatic event resembled the 9% found in the initial non-clinical study conducted by Vrana and Lauterbach (1994). The descriptive earned-secure and continuous-secure investigation demonstrated that only two participants had combined inferred mother and father loving scores ≤ 3 and both participants were classified as U in the 4-way analysis, preoccupied (E) in the 3way organized attachment analysis, and were exposed to ≥ 4 ACEs. There were 16 continuous-secure individuals. Only one individual was classified as U in the 4-way analysis and in the 3-way organized attachment classification all were secure-autonomous (F). No continuous-secure individuals were in the ≥ 4 ACEs group, 4 had 1–3 ACEs and 12 had no ACEs. These descriptive results demonstrate the buffering influence of active loving experiences provided by parents compared to the instrumental loving experienced by the two with ≤ 3 combined loving scores. See Table 2 for percentage distributions for ACE groupings. The 4-way distribution pattern for ≥ 4 ACEs demonstrated that 51.4% were deemed secure/autonomous while 40.5% were classified as U. This result demonstrates that half the group with ≥ 4 ACEs could be viewed as potentially more resilient. Adding to this resilient profile, 53.3% of those classified with U plus ≥ 4 ACEs had a secure/ autonomous secondary classification, indicating that approximately half of the individuals in this group demonstrated autonomous states of mind while discussing non-trauma/loss attachment-related experiences. However, an inability to disclose a traumatic event increased for those with ≥ 4 ACEs, a finding that suggests cumulative trauma may increase disclosure difficulty. See Table 3 for percentage of individuals with each ACE item and in the U/No-U groupings. There were more individuals in the U group on each of the ACE items, the ≥ 4 ACE group, and an inability to disclose a traumatic event. Group differences (1) Unresolved mourning, (2) ability to disclose trauma, (3) ACE prevalence, (4) geographical differences. 3.1.1. Unresolved mourning The first MANCOVA calculation (with age and gender as covariates) demonstrated significant differences between the No-U and U categorical groupings (Wilks’s Λ = .868, F(2,107) = 8.163, p = .001, η2 = .132). The pairwise comparison analyses demonstrated significant differences. Total ACE (p < .001) and total TEQ (p = .023) were significantly elevated in the U grouping compared to the No-U group. No significant differences were found for the covariate gender (p = .596) and the covariate age (p = .371). See Table 4. 3.1.2. Disclosure difficulty The second MANCOVA calculation (with age and gender as covariates) demonstrated significant differences between the Tell and No-Tell categorical groupings (Wilks’s Λ = .661, F(3,106) = 1 8.130, p = .000, η2 = .331). The pairwise comparison analyses 259 Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque Table 3 Descriptive Prevalence: Percentage of participants (Full Sample, No-U and U groups) who experienced ACE Items, Total ACEs, and Cannot Tell. Category Full Sample % No-U % U % ACE #1 Abuse – Emotional ACE #2 Abuse – Physical ACE #3 Abuse – Sexual ACE #4 Neglect – Emotional ACE #5 Neglect – Physical ACE #6 Family Dysfunction – Separated/Divorced ACE #7 Family Dysfunction – Domestic Violence ACE #8 Family Dysfunction – Addiction ACE #9 Family Dysfunction – Mental Illness ACE #10 Family Dysfunction – Prison 0 ACEs 1–3 ACEs ≥ 4 ACEs Cannot Tell 43.3 31.5 16.5 17.3 7.9 37.8 14.2 24.4 37.8 7.1 33.1 37.8 29.1 9.5 35.6 18.9 10 12.2 3.3 36.7 11.1 18.9 30 5.6 42.2 37.8 20 6 62.2 62.2 32.4 29.7 18.9 40.5 21.6 37.8 56.8 10.8 10.8 37.8 51.4 18.8 Abbreviations: ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences, No-U = < 5 on continuous Unresolved-all scale (highest score for trauma or loss); U = ≥ 5 on Uall. demonstrated significant dimensional scale differences. The AAI Uall scale (p = .029), total ACE (p = .024), and total TEQ (p < .001) were significantly elevated in the No-Tell compared to the Tell grouping. This group comparison analysis suggests that difficulty disclosing past trauma is associated with cumulative trauma and adversity, as well as receiving higher scores on the continuous unresolved mourning scale. No significant differences were found for the covariate gender (p = .988) and the covariate age (p = .502). See Table 4. 3.1.3. ACEs Group differences (0 ACE, 1–3 ACE, and ≥ 4 ACE) were significant in the third MANCOVA calculation (with age and gender as covariates) (Wilks’s Λ = .768, F(6,210) = 4.944, p < .001, η2 = .130). The pairwise comparison analyses demonstrated significant differences between the 0 ACE and ≥ 4 ACE groups for Uall (p < .001), TEQ total (p = .018) and AAI Security Index (p = .004). Between groups with 1–3 ACEs and ≥ 4 ACE there were significant differences for Uall (p = .012) and TEQ total (p = .004). This analysis demonstrated that greater cumulative ACEs negatively influence degree of resolution for past trauma, more total traumatic events in adulthood, and less attachment security. No differences were found for the covariates age (p = .247) and gender (p = .334). See Table 5. 3.1.4. Geographical differences For descriptive purposes, a fourth MANCOVA was calculated to determine group differences on the continuous scales. There were no significant differences between participants who resided in Toronto, Cape Town or Los Angeles (Wilks’s Λ = .567, F(16,46) = .942, p < .531, η2 = .247). The lack of significant differences suggests that the geographical location did not influence attachment security, degree of resolution for trauma/loss, total traumatic events, and cumulative ACEs 4. Discussion The results of this study demonstrated a strong relationship between increased ACEs and greater attachment insecurity. Specifically, the group differences for individuals who experienced no ACE (n = 42, 33.1%), those with 1–3 ACEs (n = 48, 37.8%), and those with ≥ 4 ACEs (n = 37, 29.1%) revealed a pattern in which increased group ACE exposure was associated with greater lack of resolution for past trauma/loss experiences, more adult traumatic events, and more difficulty disclosing past trauma. Similarly, when the group was divided into those classified as U versus No-U, the U group had significantly more adult traumatic Table 4 Group Mean Descriptive Statistics and Standard Deviations (SD) and MANCOVA Analyses for No-U/U Groupings and Tell/No-Tell Groupings. Uall TEQ total ACE total No-U U Tell No-Tell – 2.31(1.95) 1.84(2.22) – 3.35(2.44)* 3.81(2.59)*** 4.11(2.48) 2.19(1.68) 2.21(2.34) 5.30(1.62)* 6.36(2.29)*** 4.00(3.19)* Abbreviations: No-U = Categorical No-Unresolved Group, U − Categorical Unresolved Group (≥5), Tell = Able to tell others about trauma, No-Tell = Unable to tell others about trauma, Uall = AAI unresolved mourning dimensional scale, TEQ = Traumatic Event Questionnaire, ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences, 2) MANCOVA (age and gender covariates) comparison of mean scores showing significant group No-U/U group differences Unresolved group (≥5) (Wilks’s Λ = .868, F (2,107) = 8.163, p = .001, η2 = .132) 3) MANCOVA (age and gender covariates) comparison of mean scores showing significant group Tell/No-Tell group differences (Wilks’s Λ = .661, F(3,106) = 18.130, p < .001, η2 = .331). * p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. 260 Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque Table 5 Group Mean Descriptive Statistics, Standard Deviations (SD) and MANCOVA Analysis for Three ACE Groupings. Uall TEQ total Security Index 0 ACE 1–3 ACE ≥4 ACE 3.43(1.22) 2.03(1.62) 3.79(.96) 4.14(1.52) 2.29(1.75) 3.24(1.37) 5.23(1.83)** 3.64(2.73)*** 2.76(1.58)** Abbreviations: Uall = Dimensional Unresolved Scale, TEQ = Traumatic Event Questionnaire, MANCOVA (age and gender covariates) comparison of mean scores showing significant group differences (Wilks’s Λ = .768, F(6,210) = 4.944, p < .001, η2 = .130). * p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. events, ACEs and more difficulty disclosing past trauma (a behavior that is associated with more pathology, both psychological and physical) (Smith et al., 2000; Ullman, 2007). The relationship between resilience and ≥ 4 ACEs was also revealed in this study. Within this ≥ 4 ACEs group, 51.4% were not unresolved or insecure based on the AAI classifications. This group of individuals, with high exposure to childhood maltreatment, managed to discuss past attachment-related and trauma/loss experiences with coherence and attentional flexibility (Hesse & Main, 2000). Also, 53.3% of the U group who were also part of the ≥ 4 ACEs group was deemed secure/autonomous as their secondary classification. These findings demonstrate that, despite exposure to high ACEs, the majority of the group may manifest more psychological resilience due to attachment security. Other resilience factors in this sample may include the fact that all participants had college education (Oliver et al., 2006). They also were currently engaged in self-identified meaningful activities (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). All these factors can potentiate resilience (Masten, 2001; Walsh et al., 2007). Alternatively, the high prevalence of attachment security may support abilities to actively seek solutions (Main, 2000) necessary to succeed in higher education and to participate in meaningful activities. Study findings indicated that 29.1% of the sample had ≥ 4 ACEs; whereas, 33.1% had no exposure to childhood adversity. In the original ACE study, 12.5% of the sample was exposed to ≥ 4 ACEs (Felitti et al., 1998); although in a later community sample study this group found the same exposure pattern as the Murphy et al. (2014) study (26.5%) (Dube et al., 2003). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that ≥ 4 ACEs exposure rates may be higher than originally reported. Based on this study every participant reported at least one significant loss or trauma/abuse event, with the majority reporting both. 4.1. Limitations The limitations of this study included a relatively small sample size. The sample consisted of college-educated participants. This educational status may suggest that the sample had a higher I/Q (although not directly tested). This may be a protective factor, especially in the group with ≥ 4 ACEs; however, higher intelligence can also increase a stress response (Luthar, 1991). Because the sample is more homogenous, results may be less generalizable. A heterogeneous sample may have supported more generalizable statements. The study inclusionary criterion to be engaged in a meaningful activity was not directly measured beyond individual selfidentification that was reported in the general demographic self-report questionnaire form. Future studies should directly measure this variable to quantify the assessment of meaningful activities. The inclusion of self-report measurements increases subjective biases; however, the test-retest results strongly supported temporal stability in these instruments. Lastly, any study that investigates past trauma and abuse may influence the degree of disclosure, especially for those who are not able to speak about past trauma (Becker-Blease & Freyd, 2006). By including the AAI, unconscious lapses of monitoring that belie unresolved mourning may reduce disclosure complications. The AAI is the only instrument that can determine degree of resolution; it is not based on veridical assessment but rather the state of mind of the speaker who is discussing past experiences (Main et al., 2003). 4.2. Recommendations and conclusions Based on the findings from this community sample, it is recommended that treating individuals with unresolved trauma or loss should include probing for cumulative ACE exposure. Perhaps the emotional support of alternative others may promote earned attachment security (Saunders et al., 2011), although continuous emotional support from parental figures is the major ingredient for attachment security (Bailey et al., 2017), and in this study it was associated with no ACE exposure. Promoting engagement in selfidentified meaningful activities may also enhance resilience (Masten, 2001; Masten & Obradovic, 2006; Thomson & Jaque, 2016). Programs that incorporate narrative writing and social support during trauma disclosure may also foster psychological resolution for past trauma (Creech, Smith, Grimes, & Meagher, 2011; Smith et al., 2000; Ullman, 2007). Reducing self-blame and increasing selfefficacy may further promote psychological resolution for past childhood adversity (Ullman, 2007). McGloin and Widom (2001) reported that 22% of adults who were abused and neglected as children were considered resilient. For some individuals, adversity may actually enhance cognitive processing (Mittal, Griskevicius, Simpson, Sung, & Young, 2015). In conclusion, based on the AAI classifications almost half the sample who were exposed to ≥4 ACEs demonstrated secure states of mind regarding past attachment, trauma and loss experiences. Even though this high ACE group experienced more past traumatic events, they remained active and engaged. Stronger cognitive and social abilities operate as protective factors that enhance resilience (Ponce-Garcia, Madewell, & Brown, 2016). These factors may also promote resilience in the active participants in this study. Likewise, adversity may actually encourage the cultivation of more social support, goal efficacy, task efficacy, and planning behaviors; factors 261 Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque that augment resilience to adversity (Masten & Obradovic, 2006; Seery et al., 2010). Acknowledgement Thank you to the two reliable coders, Dr. Joanne Seltzer and Melissa Mose, who participated in double coding the AAIs (the first author was the primary reliable coder). No Funding Sources. References Bailey, H. N., Tarabulsy, G. M., Moran, G., Pederson, D. R., & Bento, S. (2017). New insight on intergenerational attachment from a relationship-based analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 433–448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000098. Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1993). A psychometric study of the Adult Attachment Interview: Reliability and discriminant validity. Developmental Psychopathology, 29, 870–880. Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2009). The first 10,000 adult attachment interviews: Distributions of adult attachment representations in clinical and non-clinical groups. Attachment and Human Development, 11, 223–263. Becker-Blease, K. A., & Freyd, J. J. (2006). Research participants telling the truth about their lives: The ethics of asking or not asking about abuse. American Psychologist, 61(3), 218–226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.61.3.218. Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent–child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books Inc. Collishaw, S., Pickles, A., Messer, J., Rutter, M., Shearer, C., & Maughan, B. (2007). Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 211–229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/chiabu.2007.02.004. Creasey, G. (2002). Psychological distress in college-aged women: Links with unresolved/preoccupied attachment status and the mediating role of negative mood regulation expectancies. Attachment and Human Development, 4(3), 261–277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616730210167249. Creech, S. K., Smith, J., Grimes, J. S., & Meagher, M. W. (2011). Written emotional disclosure of trauma and trauma history alter pain sensitivity. Journal of Pain, 12(7), 801–810. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2011.01.007. Crespo, M., & Fernandez-Lansac, V. (2015). Memory and narrative of traumatic events: A literature review. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(2), 149–156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra000041. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row. Dong, M., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., Giles, W. H., & Felitti, V. J. (2003). The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 625–639. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00105-4. Dong, M., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., Williamson, D. F., Thompson, T. T., ... Giles, W. H. (2004). The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28, 771–784. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., Chapman, D. P., Giles, W., & Anda, R. F. (2003). Childhood abuse: household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics, 111, 564–572. Dykas, M. J., Woodhouse, S. S., Jones, J. D., & Cassidy, J. (2014). Attachment-related biases in adolescents’ memory. Child Development, 85(6), 2185–2201. http://dx. doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12268. Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2010). The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult medical disease, psychiatric disorders and sexual behavior: Implications for healthcare. In R. A. Lanius, E. Vermetten, & C. Pain (Eds.), The impact of early life trauma on health and disease: The hidden epidemic (pp. 77–87). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., ... Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. Hesse, E., & Main, M. (2000). Disorganized infant, child, and adult attachment. Collapse in behavioral and attentional strategies. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 48, 1097–1127. Hesse, E. (2008). The Adult Attachment Interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and empirical studies. In J. Cassidy, & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 552–598). New York: The Guilford Press. Jacobvitz, D., Curran, M., & Moller, N. (2002). Measurement of adult attachment: The place of self-report and interview methodologies. Attachment and Human Development, 4(2), 207–215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616730210154225. Kessler, B. L., & Bieschke, K. J. (1999). A retrospective analysis of shame, dissociation, and adult victimization in survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46(3), 335–341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.46.3.33. Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., ... Williams, D. R. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197, 378–385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. Lauterbach, D., & Vrana, S. (2001). The relationship among personality variables: exposure to traumatic events and severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 29–38. Luthar, S. S. (1991). Vulnerability and resilience: A study of high-risk adolescents. Child Development, 62(3), 600–616. Main, M., Goldwyn, R., & Hesse, E. (2003). Adult attachment scoring and classification systems. Unpublished manuscript. University of California at Berkeley. Main, M. (2000). The organized categories of infant, child and adult attachment: Flexible vs. inflexible attention under attachment-related stress. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 48(4), 1055–1096. Masten, A. S., & Obradovic, J. (2006). Competence and resilience in development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 13–27. http://dx.doi.org/10. 1196/annals.1376.003. Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0003.066X.56.3.227. McGloin, J. M., & Widom, C. S. (2001). Resilience among abused and neglected children grown up. Development and Psychopathology, 13(4), 1021–1038. Mittal, C., Griskevicius, V., Simpson, J. A., Sung, S., & Young, E. S. (2015). Cognitive adaptations to stressful environments: When childhood adversity enhances adult executive functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(4), 604–621. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi000028. Murphy, A., Steele, M., Dube, S. R., Bate, J., Bonuck, K., Meissner, P., ... Steele, H. (2014). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire and Adult Attachment Interview (AAI): Implications for parent child relationships. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38, 224–233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.004. Oliver, K. G., Collin, P., Burns, J., & Nicholas, J. (2006). Building resilience in young people through meaningful participation. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 5(1), 1–7. Ponce-Garcia, E., Madewell, A. N., & Brown, M. E. (2016). Resilience in men and women experiencing sexual assault or traumatic stress: Validation and replication of the Scale of Protective Factors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29, 537–545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.22148. Raby, K. L., Labella, M. H., Martin, J., Carlson, E. A., & Roisman, G. I. (2017). Childhood abuse and neglect and insecure attachment states of mind in adulthood: Prospective, longitudinal evidence from a high-risk sample. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 347–363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000037. Roisman, G. I., Fraley, R. C., & Belsky, J. (2007). A taxometric study of the Adult Attachment Interview. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 675–686. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/0012-1649.43.3.675. Rutter, I. M. (2006). Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 1–12. http://dx.doi.org/10. 262 Child Abuse & Neglect 70 (2017) 255–263 P. Thomson, S.V. Jaque 1196/annals.1376.002. Saunders, R., Jacobvitz, D., Zaccagnino, M., Beverung, L. M., & Hazen, N. (2011). Pathways to earned-security: The role of alternative support figures. Attachment and Human Development, 13(4), 403–420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2011.584405. Seery, M. D., Holman, E. A., & Silver, R. C. (2010). Whatever does not kill us: Cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(6), 1025–1041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0021344. Smith, D. W., Letourneau, E. J., Saunders, B. E., Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., & Best, C. L. (2000). Delay in disclosure of childhood rape: Results from a national survey. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24(2), 273–287. Thomson, P., & Jaque, S. V. (2012). Dissociation and the Adult Attachment Interview in artists. Attachment and Human Development, 14(2), 145–160. Thomson, P., & Jaque, S. V. (2016). Visiting the muses: Creativity, coping and PTSD in talented dancers and athletes. American Journal of Play, 8(3), 363–378. Ullman, S. E., Foynes, M. M., & Tang, S. S. (2010). Benefits and barriers to disclosing sexual trauma: A contextual approach. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 11, 127–133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299730903502904. Ullman, S. E. (2007). Relationship to perpetrator, disclosure, social reactions, and PTSD symptoms in child sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 16(1), 19–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/j070v16n01_02. Vrana, S., & Lauterbach, D. (1994). Prevalence of traumatic events and posttraumatic psychological symptoms in a non-clinical sample of college students. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7, 298–302. Walsh, K., Blaustein, M., Knight, W. G., Spinazzola, J., & van der Kolk, B. A. (2007). Resiliency factors in the relation between childhood sexual assault and adulthood sexual assault in college-age women. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 16(1), 1–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J070v16n01_01. Weinfield, N. S., Whaley, G. J. L., & Egeland, B. (2004). Continuity, discontinuity: and coherence in attachment from infancy to late adolescence: Sequelae of organization and disorganization. Attachment and Human Development, 6, 73–97. Wright, M. O., Crawford, E., & Del Castillo, D. (2009). Childhood emotional maltreatment and later psychological distress among college students: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33, 59–68. 263