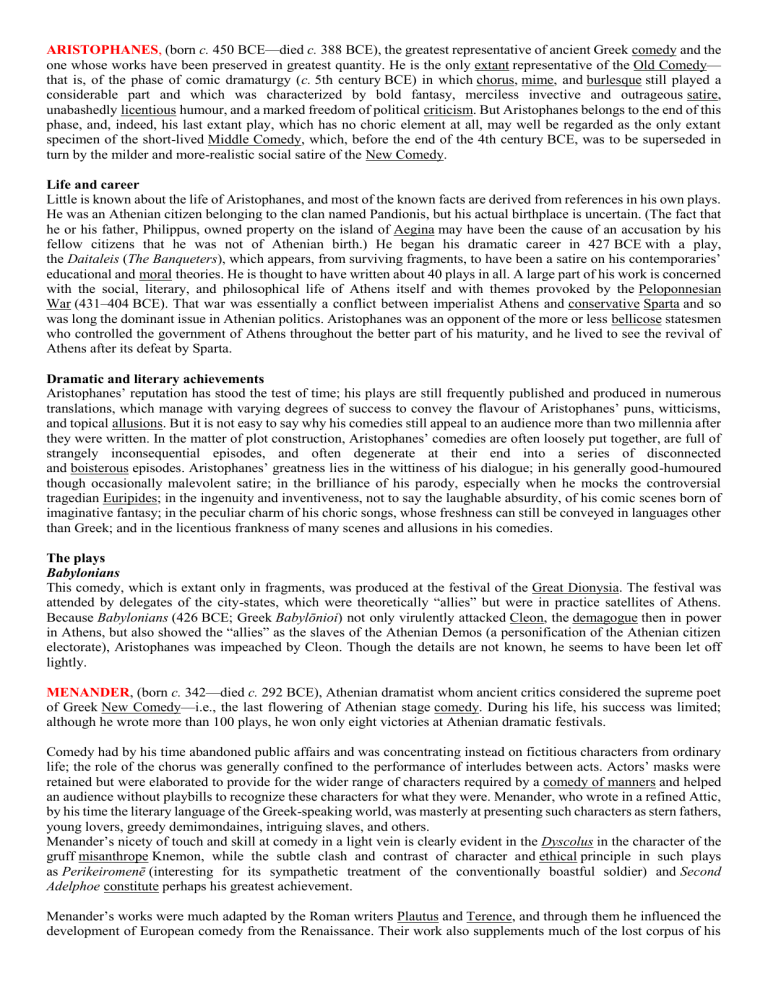

ARISTOPHANES, (born c. 450 BCE—died c. 388 BCE), the greatest representative of ancient Greek comedy and the one whose works have been preserved in greatest quantity. He is the only extant representative of the Old Comedy— that is, of the phase of comic dramaturgy (c. 5th century BCE) in which chorus, mime, and burlesque still played a considerable part and which was characterized by bold fantasy, merciless invective and outrageous satire, unabashedly licentious humour, and a marked freedom of political criticism. But Aristophanes belongs to the end of this phase, and, indeed, his last extant play, which has no choric element at all, may well be regarded as the only extant specimen of the short-lived Middle Comedy, which, before the end of the 4th century BCE, was to be superseded in turn by the milder and more-realistic social satire of the New Comedy. Life and career Little is known about the life of Aristophanes, and most of the known facts are derived from references in his own plays. He was an Athenian citizen belonging to the clan named Pandionis, but his actual birthplace is uncertain. (The fact that he or his father, Philippus, owned property on the island of Aegina may have been the cause of an accusation by his fellow citizens that he was not of Athenian birth.) He began his dramatic career in 427 BCE with a play, the Daitaleis (The Banqueters), which appears, from surviving fragments, to have been a satire on his contemporaries’ educational and moral theories. He is thought to have written about 40 plays in all. A large part of his work is concerned with the social, literary, and philosophical life of Athens itself and with themes provoked by the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE). That war was essentially a conflict between imperialist Athens and conservative Sparta and so was long the dominant issue in Athenian politics. Aristophanes was an opponent of the more or less bellicose statesmen who controlled the government of Athens throughout the better part of his maturity, and he lived to see the revival of Athens after its defeat by Sparta. Dramatic and literary achievements Aristophanes’ reputation has stood the test of time; his plays are still frequently published and produced in numerous translations, which manage with varying degrees of success to convey the flavour of Aristophanes’ puns, witticisms, and topical allusions. But it is not easy to say why his comedies still appeal to an audience more than two millennia after they were written. In the matter of plot construction, Aristophanes’ comedies are often loosely put together, are full of strangely inconsequential episodes, and often degenerate at their end into a series of disconnected and boisterous episodes. Aristophanes’ greatness lies in the wittiness of his dialogue; in his generally good-humoured though occasionally malevolent satire; in the brilliance of his parody, especially when he mocks the controversial tragedian Euripides; in the ingenuity and inventiveness, not to say the laughable absurdity, of his comic scenes born of imaginative fantasy; in the peculiar charm of his choric songs, whose freshness can still be conveyed in languages other than Greek; and in the licentious frankness of many scenes and allusions in his comedies. The plays Babylonians This comedy, which is extant only in fragments, was produced at the festival of the Great Dionysia. The festival was attended by delegates of the city-states, which were theoretically “allies” but were in practice satellites of Athens. Because Babylonians (426 BCE; Greek Babylōnioi) not only virulently attacked Cleon, the demagogue then in power in Athens, but also showed the “allies” as the slaves of the Athenian Demos (a personification of the Athenian citizen electorate), Aristophanes was impeached by Cleon. Though the details are not known, he seems to have been let off lightly. MENANDER, (born c. 342—died c. 292 BCE), Athenian dramatist whom ancient critics considered the supreme poet of Greek New Comedy—i.e., the last flowering of Athenian stage comedy. During his life, his success was limited; although he wrote more than 100 plays, he won only eight victories at Athenian dramatic festivals. Comedy had by his time abandoned public affairs and was concentrating instead on fictitious characters from ordinary life; the role of the chorus was generally confined to the performance of interludes between acts. Actors’ masks were retained but were elaborated to provide for the wider range of characters required by a comedy of manners and helped an audience without playbills to recognize these characters for what they were. Menander, who wrote in a refined Attic, by his time the literary language of the Greek-speaking world, was masterly at presenting such characters as stern fathers, young lovers, greedy demimondaines, intriguing slaves, and others. Menander’s nicety of touch and skill at comedy in a light vein is clearly evident in the Dyscolus in the character of the gruff misanthrope Knemon, while the subtle clash and contrast of character and ethical principle in such plays as Perikeiromenē (interesting for its sympathetic treatment of the conventionally boastful soldier) and Second Adelphoe constitute perhaps his greatest achievement. Menander’s works were much adapted by the Roman writers Plautus and Terence, and through them he influenced the development of European comedy from the Renaissance. Their work also supplements much of the lost corpus of his plays, of which no complete text exists, except that of the Dyscolus, first printed in 1958 from some leaves of a papyrus codex acquired in Egypt. The known facts of Menander’s life are few. He was allegedly rich and of good family, and a pupil of the philosopher Theophrastus, a follower of Aristotle. In 321 Menander produced his first play, Orgē (“Anger”). In 316 he won a prize at a festival with the Dyscolus and gained his first victory at the Dionysia festival the next year. By 301 Menander had written more than 70 plays. He probably spent most of his life in Athens and is said to have declined invitations to Macedonia and Egypt. He allegedly drowned while swimming at the Piraeus (Athens’s port). NEW COMEDY GREEK DRAMA New Comedy, Greek drama from about 320 BC to the mid-3rd century BC that offers a mildly satiric view of contemporary Athenian society, especially in its familiar and domestic aspects. Unlike Old Comedy, which parodied public figures and events, New Comedy features fictional average citizens and has no supernatural or heroic overtones. Thus, the chorus, the representative of forces larger than life, recedes in importance and becomes a small band of musicians and dancers who periodically provide light entertainment. The plays commonly deal with the conventionalized situation of thwarted lovers and contain such stock characters as the cunning slave, the wily merchant, the boastful soldier, and the cruel father. One of the lovers is usually a foundling, the discovery of whose true birth and identity makes marriage possible in the end. Although it does not realistically depict contemporary life, New Comedy accurately reflects the disillusioned spirit and moral ambiguity of the bourgeois class of this period. Menander introduced the New Comedy in his works about 320 BC and became its most famous exponent, writing in a quiet, witty style. Although most of his plays are lost, Dyscolus (“The Grouch”) survives, along with large parts of Perikeiromenē (“The Shorn Girl”), Epitrepontes (“The Arbitration”), and Samia (“The Girl from Samos”). Menander’s plays are mainly known through the works of the Roman dramatists Plautus and Terence, who translated and adapted them, along with other stock plots and characters of Greek New Comedy, for the Roman stage. Revived during the Renaissance, New Comedy influenced European drama down to the 18th century. The commedia erudita, plays from printed texts popular in Italy in the 16th century, and the improvisational commedia dell’arte that flourished in Europe from the 16th to the 18th century used characters and plot conventions that originated in Greek New Comedy. They were also used by Shakespeare and other Elizabethan and Restoration dramatists. Rodgers and Hart’s The Boys from Syracuse (1938) is a musical version of Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors, which in turn is based on Plautus’s Menaechmi and Amphitruo, which are adaptations of Greek New Comedy. PLAUTUS, (born c. 254 BCE, Sarsina, Umbria? [Italy]—died 184 BCE), great Roman comic dramatist, whose works, loosely adapted from Greek plays, established a truly Roman drama in the Latin language. Life Little is known for certain about the life and personality of Plautus, who ranks with Terence as one of the two great Roman comic dramatists. His work, moreover, presents scholars with a variety of textual problems, since the manuscripts by which his plays survive are corrupt and sometimes incomplete. Nevertheless, his literary and dramatic skills make his plays enjoyable in their own right, while the achievement of his comic genius has had lasting significance in the history of Western literature and drama. According to the grammarian Festus (2nd or 3rd century CE), Plautus was born in northeastern central Italy. His customarily assigned birth and death dates are largely based on statements made by later Latin writers, notably Cicero in the 1st century BCE. Even the three names usually given to him—Titus Maccius Plautus—are of questionable historical authenticity. Internal evidence in some of the plays does, it is true, suggest that these were the names of their author, but it is possible that they are stage names, even theatrical jokes or allusions. (“Maccus,” for example, was the traditional name of the clown in the fabula Atellana (“Atellan plays”), a long-established popular burlesque that was native to the Neapolitan region of southern Italy; “Plautus,” according to Festus, derives from planis pedibus, planipes [flat-footed] being a pantomime dancer.) There are further difficulties: the poet Lucius Accius (170–c. 86 BCE), who made a study of his fellow Umbrian, seems to have distinguished between one Plautus and one Titus Maccius. Tradition has it that Plautus was associated with the theatre from a young age. An early story says that he lost the profits made from his early success as a playwright in an unsuccessful business venture, and that for a while afterward he was obliged to earn a living by working in a grain mill. Approach to drama The Roman predecessors of Plautus in both tragedy and comedy borrowed most of their plots and all of their dramatic techniques from Greece. Even when handling themes taken from Roman life or legend, they presented these in Greek forms, setting, and dress. Plautus, like them, took the bulk of his plots, if not all of them, from plays written by Greek authors of the late 4th and early 3rd centuries BCE (who represented the New Comedy, as it was called), notably Menander and Philemon. Plautus did not, however, borrow slavishly; although the life represented in his plays is superficially Greek, the flavour is Roman, and Plautus incorporated into his adaptations Roman concepts, terms, and usages. He referred to towns in Italy; to the gates, streets, and markets of Rome; to Roman laws and the business of the Roman law courts; to Roman magistrates and their duties; and to such Roman institutions as the Senate. Not all references, however, were Romanized: Plautus apparently set little store by consistency, despite the fact that some of the Greek allusions that were left may have been unintelligible to his audiences. Terence, the more studied and polished playwright, mentions Plautus’s carelessness as a translator and upbraids him for omitting an entire scene from one of his adaptations from the Greek (though there is no criticism of him for borrowing material, such plagiarism being then regarded as wholly commendable). Plautus allowed himself many other liberties in adapting his material, even combining scenes from two Greek originals into one Latin play (a procedure known as contaminatio). Even more important was Plautus’s approach to the language in which he wrote. His action was lively and slapstick, and he was able to marry the action to the word. In his hands, Latin became racy and colloquial, verse varied and choral. Whether these new characteristics derived from now lost Greek originals—more vigorous than those of Menander—or whether they stemmed from the established forms and tastes of burlesque traditions native to Italy cannot be determined with any certainty. The latter is more likely. The result, at any rate, is that Plautus’s plays read like originals rather than adaptations, such is his witty command of the Latin tongue—a gift admired by Cicero himself. It has often been said that Plautus’s Latin is crude and “vulgar,” but it is in fact a literary idiom based upon the language of the Romans in his day. The plots of Plautus’s plays are sometimes well organized and interestingly developed, but more often they simply provide a frame for scenes of pure farce, relying heavily on intrigue, mistaken identity, and similar devices. Plautus is a truly popular dramatist, whose comic effect springs from exaggeration, burlesque and often coarse humour, rapid action, and a deliberately upside-down portrayal of life, in which slaves give orders to their masters, parents are hoodwinked to the advantage of sons who need money for girls, and the procurer or braggart soldier is outwitted and fails to secure the seduction or possession of the desired girls. Plautus, however, did also recognize the virtue of honesty (as in Bacchides), of loyalty (as in Captivi), and of nobility of character (as in the heroine of Amphitruo). Plautus’s plays, almost the earliest literary works in Latin that have survived, are written in verse, as were the Greek originals. The metres he used included the iambic six foot line (senarius) and the trochaic seven foot line (septenarius), which Menander had also employed. But Plautus varied these with longer iambic and trochaic lines and more elaborate rhythms. The metres are skillfully chosen and handled to emphasize the mood of the speaker or the action. Again, it is possible that now lost Greek plays inspired this metrical variety and inventiveness, but it is much more likely that Plautus was responding to features already existing in popular Italian dramatic traditions. The Senarii (conversational lines) were spoken, but the rest was sung or chanted to the accompaniment of double and fingered reed pipes, or auloi. It could indeed be said that, in their metrical and musical liveliness, performances of Plautus’s plays somewhat resembled musicals of the mid-20th century. Although Plautus’s original texts did not survive, some version of 21 of them did. Even by the time that Roman scholars such as Varro, a contemporary of Cicero, became interested in the playwright, only acting editions of his plays remained. These had been adapted, modified, cut, expanded, and generally brought up-to-date for production purposes. Critics and scholars have ever since attempted to establish a “Plautine” text, but 20th- and 21st-century editors have admitted the impossibility of successfully accomplishing such a task. The plays had an active stage life at least until the time of Cicero and were occasionally performed afterward. Whereas Cicero had praised their language, the poet Horace was a more severe critic and considered the plays to lack polish. There was renewed scholarly and literary interest in Plautus during the 2nd century CE, but it is unlikely that this was accompanied by a stage revival, though a performance of Casina is reported to have been given in the early 4th century. St. Jerome, toward the end of that century, says that after a night of excessive penance he would read Plautus as a relaxation; in the mid-5th century, Sidonius Apollinaris, a Gallic bishop who was also a poet, found time to read the plays and praise the playwright amid the alarms of the barbarian invasions. During the Middle Ages, Plautus was little read if at all—in contrast to the popular Terence. By the mid-14th century, however, the humanist scholar and poet Petrarch knew eight of the comedies. As the remainder came to light, Plautus began to influence European domestic comedy after the Renaissance poet Ariosto made the first imitations of Plautine comedy in the Italian vernacular. His influence was perhaps to be seen at its most sophisticated in the comedies of Molière (whose play L’Avare, for instance, was based on Aulularia), and it can be traced up to the 20th century in such adaptations as Jean Giraudoux’s Amphitryon 38 (1929), Cole Porter’s musical Out of This World (1950), and the musical and motion picture A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1963). Plautus’s stock character types have similarly had a long line of successors: the braggart soldier Miles Gloriosus, for example, became the Capitano of the Italian commedia dell’arte and is recognizable in Nicholas Udall’s Ralph Roister Doister (16th century), in Shakespeare’s Pistol and even in his Falstaff, in Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac (1897), and in Bernard Shaw’s Sergius in Arms and the Man (1894). A trace of the character perhaps remains even in Bertolt Brecht’s Eilif in Mother Courage and Her Children (1941). Thus, Plautus, in adapting Greek New Comedy to Roman conditions and taste, also significantly affected the course of the European theatre. TERENCE, Latin in full Publius Terentius Afer, (born c. 195 BC, Carthage, North Africa [now in Tunisia]—died 159? BC, in Greece or at sea), after Plautus the greatest Roman comic dramatist, the author of six verse comedies that were long regarded as models of pure Latin. Terence’s plays form the basis of the modern comedy of manners. Terence was taken to Rome as a slave by Terentius Lucanus, an otherwise unknown Roman senator who was impressed by his ability and gave him a liberal education and, subsequently, his freedom. Reliable information about the life and dramatic career of Terence is defective. There are four sources of biographical information on him: a short, gossipy life by the Roman biographer Suetonius, written nearly three centuries later; a garbled version of a commentary on the plays by the 4th-century grammarian Aelius Donatus; production notices prefixed to the play texts recording details of first (and occasionally also of later) performances; and Terence’s own prologues to the plays, which, despite polemic and distortion, reveal something of his literary career. Most of the available information about Terence relates to his career as a dramatist. During his short life he produced six plays, to which the production notices assign the following dates: Andria (The Andrian Girl), 166 BC; Hecyra (The Mother-inLaw), 165 BC; Heauton timoroumenos (The Self-Tormentor), 163 BC; Eunuchus (The Eunuch), 161 BC; Phormio, 161 BC; Adelphi (or Adelphoe; The Brothers), 160 BC; Hecyra, second production, 160 BC; Hecyra, third production, 160 BC. These dates, however, pose several problems. The Eunuchus, for example, was so successful that it achieved repeat performance and record earnings for Terence, but the prologue that Terence wrote, presumably a year later, for the Hecyra’s third production gives the impression that he had not yet achieved any major success. From the beginning of his career, Terence was lucky to have the services of Lucius Ambivius Turpio, a leading actor who had promoted the career of Caecilius, the major comic playwright of the preceding generation. Now in old age, the actor did the same for Terence. Yet not all of Terence’s productions enjoyed success. The Hecyra failed twice: its first production broke up in an uproar when rumours were circulated among its audience of alternative entertainment by a tightrope walker and some boxers; and the audience deserted its second production for a gladiatorial performance nearby. Terence faced the hostility of jealous rivals, particularly one older playwright, Luscius Lanuvinus, who launched a series of accusations against the newcomer. The main source of contention was Terence’s dramatic method. It was the custom for these Roman dramatists to draw their material from earlier Greek comedies about rich young men and the difficulties that attended their amours. The adaptations varied greatly in fidelity, ranging from the creative freedom of Plautus to the literal rendering of Luscius. Although Terence was apparently fairly faithful to his Greek models, Luscius alleged that Terence was guilty of “contamination”—i.e., that he had incorporated material from secondary Greek sources into his plots, to their detriment. Terence sometimes did add extraneous material. In the Andria, which, like the Eunuchus, Heauton timoroumenos, and Adelphi, was adapted from a Greek play of the same title by Menander, he added material from another Menandrean play, the Perinthia (The Perinthian Girl). In the Eunuchus he added to Menander’s Eunouchos two characters, a soldier and his “parasite”—a hanger-on whose flattery of and services to his patron were rewarded with free dinners—both of them from another play by Menander, the Kolax (The Parasite). In the Adelphi, he added an exciting scene from a play by Diphilus, a contemporary of Menander. Such conservative writers as Luscius objected to the freedom with which Terence used his models. A further allegation was that Terence’s plays were not his own work but were composed with the help of unnamed nobles. This malicious and implausible charge is left unanswered by Terence. Romans of a later period assumed that Terence must have collaborated with the Scipionic circle, a coterie of admirers of Greek literature, named after its guiding spirit, the military commander and politician Scipio Africanus the Younger. Terence died young. When he was 35, he visited Greece and never returned from the journey. He died either in Greece from illness or at sea by shipwreck on the return voyage. Of his family life, nothing is known, except that he left a daughter and a small but valuable estate just outside Rome on the Appian Way.