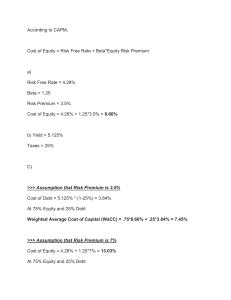

Revisiting the Equity Risk Premium: CFA Institute Monograph

advertisement