Monopolistic Competition: Definition, Demand, and Equilibrium

advertisement

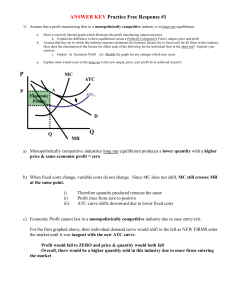

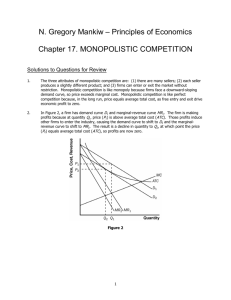

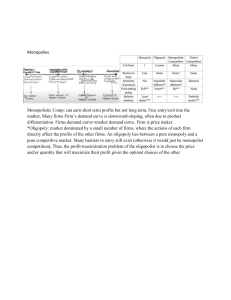

CHAPTER ONE MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION Instructor: Aschalew SH. Monopolistic Competition Defined • As the name implies, monopolistic competition is a blend of competition and monopoly. – It possesses some elements or characteristics of perfect competition and draws some elements from pure monopoly. • The competitive element arises because there are many sellers, each of which is too small to significantly affect the other sellers. • In addition, firms can enter and leave a monopolistically competitive industry. Thus, the major elements of perfect competition found in monopolistic competition are: – the existence of many small firms which are unable to significantly affect each other (when seen individually), and – the possibility of entry and exit. Cont’d • The monopolistic element arises from product differentiation. – since the product of each seller is similar but not identical, each seller has a monopoly power over the specific product it sells. • This monopoly power, however, is severely limited by the existence of close substitutes. – Examples of monopolistic competition include the markets of the numerous brands of soap (B-29, Wabel, 777 …), toothpaste (Aquafresh, Colgate, Close-Up …), stationeries (SinarLine, MAMCO …), cigarettes (Rothmans, Marlboro, Nyala, Dunhill …), etc. • Edward Chamberlin (1933) and Joan Robinson (1933) contributed the pioneering works on monopolistic competition. Product Differentiation, the Demand Curves & Costs of the Firm • Product Differentiation: • Product differentiation is generally intended to distinguish the product of one producer from that of the others in the ‘industry.’ This product differentiation might be attributed to: – The subjective judgment of the consumer, – The quality (for instance, the durability) of the product, – The characteristics of the product such as taste, color , – Sales promotion, packaging, trademarks, etc. • Product differentiation can be real or fancied. Cont’d • Real product differentiation: exists when there are d/ces in the specification of the products (chemical composition/ ingredients), or d/ces in the factor inputs, or the services offered by the producer during times of sale. • As long as there is a d/ce in what the consumer or the buyer actually gets, whether it is a d/ce of chemical composition or a d/ce of the accompanying service, the product differentiation is real. Cont’d • Fancied (spurious/imaginary) product differentiation: exists when the products are basically the same but the consumer is persuaded, via advertising or other selling activities, that the products are different. It is established by advertising, difference in packaging, difference in design, or simply by brand name. • Whatever the case, the aim of product differentiation is to make the product unique in the mind of the consumer. Demand Curve • One major implication of product differentiation is that the producer has some power in the determination of its product’s price. – The firm is not a price-taker but a price-maker even though it faces the keen competition of close substitutes offered by other firms. • Hence, product differentiation gives rise to a negatively sloping demand curve. • This demand curve is less elastic than perfectly competitive firm’s demand curve, but more elastic than the demand curve a pure monopolist faces because of the availability of close substitutes in monopolistic competition. – Unlike a wheat-farmer who cannot individually affect the market price of wheat (nearest example of perfect competitor), the producer of a cigarette brand (say, Marlboro) can set the price for its product. Cont’d • We distinguish between two types of demand curves in the theory of monopolistic competition – the planned sales curve and the actual sales curve. – The planned sales curve – this is a demand curve that shows how much the firm will sell if it varies its price from the ongoing level under the assumption that other firms maintain their existing prices. – If the firm reduces its price and other firms maintain their prices, the firm can expect a considerable increase in sales since it will be able to attract buyers away from other firms in the group (‘industry’) and increase sales to existing customers. – If the firm increases its price and other firms maintain their prices, the firm can expect a considerable decrease in sales since it will lose business to other firms in the group. Cont’d Cont’d • Thus, assuming that each firm expects its actions to go unfelt by the others, each believes its demand curve to be quite elastic. – This demand curve (the planned sales curve) is shown as dd in Figure 1.1. • If the firm under consideration charges P2 per unit, it would sell Q4 units of its output; similarly, Q* and Q3 units would be sold at prices P* and P1, respectively. • Under the assumption we made regarding what this firm thinks about its competitors, the decision of this firm to change prices implies a movement along the dd curve. Cont’d • The actual sales curve – this is the demand curve based on the assumption that all firms raise or lower their prices by the same amount as the firm under consideration. – This demand curve, also known as the share-of-the-market curve, is shown as DD in Figure 1.1. • If this firm reduces its price from P* to P1 (on the expectation of raising sales to Q3) and all other firms reduce their prices to P1 as well, this firm will sell only Q1 units of output. Cont’d • Similarly, if this firm increases its price to P2 and all other firms increase their prices to P2 as well, this firm will sell Q2 units of output. • Thus, if firms follow both price- rises and price-cuts of a firm, no shift of customers is expected to result from a price change. The only change that takes place is the change in the quantity consumed of each firm’s product in a direction opposite the direction of price change. Costs: • Chamberlin introduced the selling costs to the theory of the firm for the first time. The recognition of product differentiation provides the rationale for the selling expenses incurred by a firm. • He also argued that the selling-costs curve is U-shaped, i.e., there are economies and diseconomies of scale of advertising as output changes. The cost of advertising per unit of output initially declines and then eventually rises as output expands. Thus, there is a level of output where the ATC of advertising is minimized. • The U-shaped selling costs, added to the U-shaped production costs, yield U-shaped average, average variable, and marginal cost curves. The Concept of Industry and Product Group • An industry under perfect competitive condition is defined as a group of firms producing homogenous products. But this concept of industry cannot be applied to the cases where products are differentiated. • Chamberlain defined the monopolistically competitive industry as a group of firms producing a closely related commodity called product group. • The products in the same group can be technological and economic close substitutes among themselves. Cont’d The two products are technological substitutes for each other if technically satisfy the same want. Example: Rothman Vs Nyala, Peacock soap Vs B-29, and all vehicles. The two products are considered as economic substitutes for each other when they satisfy the same wants and have more or less the same price. Example: Meta Vs Harar beers, Coca Vs Pepsi, etc. Operationally, products in a group are close substitutes in the sense that the products are technologically as well as economically substitutes. Equilibrium of the Firm • A perfectly competitive firm is a price-taker. It can choose the level of output only. This means that quantity of output is the only choice variable for a perfect competitor. • On the other hand, a pure monopolist can choose either the price it charges or the quantity of output it produces, but cannot simultaneously choose both. • What about a monopolistically competitive firm? The choicerelated variables for a monopolistically competitive firm are: i. price (or quantity), ii. product variation, and iii. selling expenses. Cont’d • As for a firm under any type of market structure, the best level of output for a monopolistically competitive firm is determined by the equality of marginal revenue and marginal cost, i.e., (MR = MC). • Figure below depicts the three possible short run equilibria of a firm in a monopolistically competitive market structure. Cont’d Cont’d • In the long run, however, the monopolistically competitive firm breaks even. • While perfectly competitive firms reach the long run (zero profit) equilibrium as result of free entry and exit, monopolistically competitive firms reach the long run (zero profit) equilibrium because of two forces: – Free entry into and exit out of the product group, and – Price competition of the existing firms. Graphically Monopolistic versus perfect competition: excess capacity • There are two noteworthy differences between monopolistic and perfect competition: excess capacity and mark-up. • In perfect competition in the long run, firms produce at the point where ATC is minimised (efficient scale). There is no excess capacity. • In monopolistic competition in the long run firms produce output less than the efficient scale where ATC is minimised. • In other words, monopolistic competition implies excess capacity not only in the short run but also in the long run. 21 Excess capacity Monopolistically Competitive Firm Perfectly Competitive Firm Price Price MC MC ATC P = MC ATC P = MR (demand curve) Excess capacity Demand Quantity Quantity Efficient produced scale Quantity Quantity = Efficient produced scale 22 Mark-up over marginal cost • For a competitive firm, price equals marginal cost both in the short and long run due to the horizontal demand curve (price taker) P = AR = MR = MC • For a monopolistically competitive firm, price exceeds marginal cost both in the short and long run due to downward sloping demand curve (price maker). P = AR > MR = MC • Mark-up means price exceeds marginal cost. • Mark-up pricing implies that an extra unit sold at the posted price earns more profit for the firm. Profit volume depends on sale volume 23 Mark-up over marginal cost Monopolistically Competitive Firm Perfectly Competitive Firm Price Price Markup MC MC ATC P = MC P = MR (demand curve) Marginal cost MR Demand Quantity Quantity produced ATC Quantity Quantity produced 24 Monopolistic competition and the welfare of society • Monopolistic competition is less desirable for society compared with perfect competition – First and foremost, it causes deadweight loss to the society due to the markup of price over marginal cost – Excess capacity in the long run implies unused scarce resources for the society • Regulation to achieve the equality of marginal cost and revenue is not practical because it involves interfering with the pricing decisions of all the firms with differentiated products • Even an efficient and non-corrupt public administration may find this task impossible 25 Cont’d End of CH1!