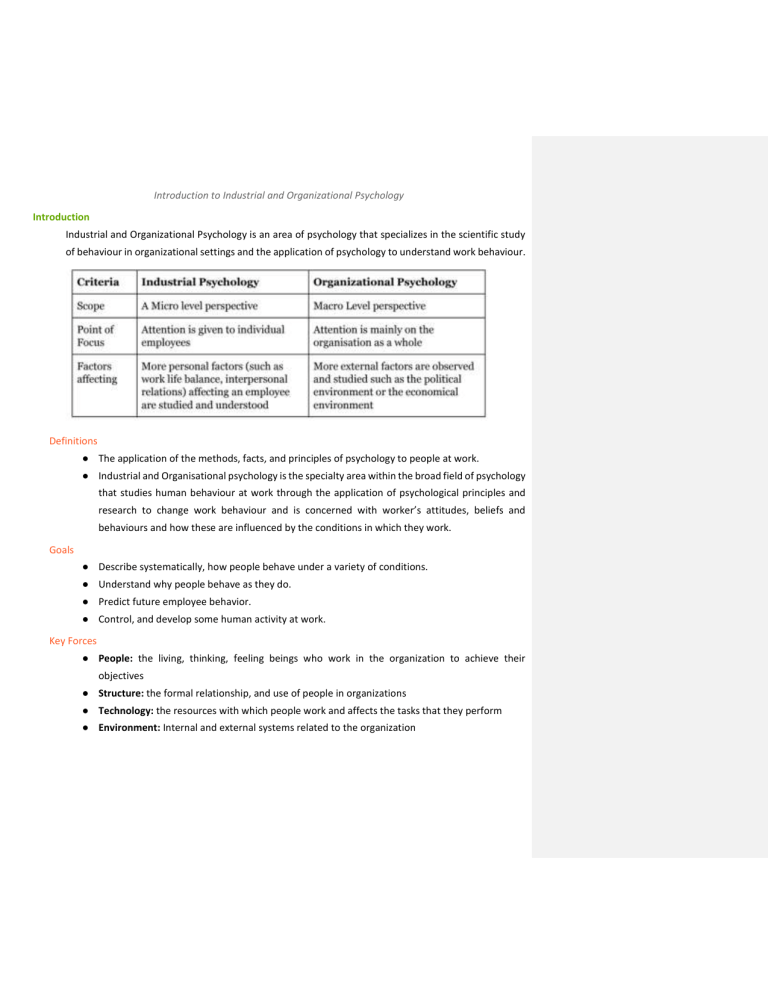

Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology Introduction Industrial and Organizational Psychology is an area of psychology that specializes in the scientific study of behaviour in organizational settings and the application of psychology to understand work behaviour. Definitions ● The application of the methods, facts, and principles of psychology to people at work. ● Industrial and Organisational psychology is the specialty area within the broad field of psychology that studies human behaviour at work through the application of psychological principles and research to change work behaviour and is concerned with worker’s attitudes, beliefs and behaviours and how these are influenced by the conditions in which they work. Goals ● Describe systematically, how people behave under a variety of conditions. ● Understand why people behave as they do. ● Predict future employee behavior. ● Control, and develop some human activity at work. Key Forces ● People: the living, thinking, feeling beings who work in the organization to achieve their objectives ● Structure: the formal relationship, and use of people in organizations ● Technology: the resources with which people work and affects the tasks that they perform ● Environment: Internal and external systems related to the organization Fundamental Concepts Nature of People ● Find people whose mental qualities make them best fitted for the work which they have to do. ● Under what psychological conditions can the greatest and most satisfactory output of work from every employee be secured. ● Cultural and Ethnic Background ● Criminal and Mental Health History ● Individual Differences ● Perception ○ The way everyone perceives the job tasks or profile differently. ○ Selective perception: Cognitive bias (eg. Favouritism, be it in a task or with an employee) Depends on background experience et cetera. ● A whole person ○ We take a person for who he is and not just his skill sets ● Motivated behaviour ○ For every individual there are different ways to get motivated ● Desire for involvement ○ Letting the employees be a part of the management ● Value of the person ○ Letting the employees be appreciated for the work done, value their skills and resources (Human resource appreciation) Nature of the Organisation ● Fundamental nature of organizations changing with elimination of layers of management, increasing employee responsibilities, restructuring in new configurations. ● Social system ○ Formal and informal groups ● Mutual Interest ○ Ensuring employees personal interests align with the organisational goals ● Ethics ○ CSR consideration History ● Adam Smith an economist in his book The Wealth of Nations (1776) introduces the concept of division of labour and its advantages using an example of a pin industry. According to him division of labour increased productivity as well as specific skills. ● Charles Babbage in his book On the Economy of Machinery and Manufacturers (1832) expanded the virtue of division of labour. He adds onto the advantages of division of labour explaining that it reduces time needed to learn a job and the waste used during the process, allows for attainment of high skill level and that it allows for a more careful matching of people’s skills and abilities with specific tasks. ● Robert Owen, an entrepreneur for the first time in history criticized child labour, the working time which was 13 hours then and the the attitude of valuing the equipment more than the human resource by the manufacturers. Wanted to bring changes in child labour laws, regulation of work hours, CSR, meals. The Classic Era ● Frederick Taylor, constantly appalled by the inefficiency of workers developed a scientific method to improve productivity and invested his time to find out the one best way for each job to be done for instance through his Bethlehem experiment to figure out the best way for pig-iron handling. He came up with four principles of management; ○ Develop a science for each element of an individual’s work (Replace Rule of thumb) ○ Scientifically select and then train, each and develop the worker ○ Heartily co-operate with the workers so as to ensure that all work is done in accordance with the principles of science that has been developed ○ Divide work and responsibility almost equally between management and workers (instead of throwing all the responsibility over the workers) ● Chester Bernard encouraged managers to develop a sense of common purpose where willingness to cooperate is strongly encouraged. Developed acceptance theory of management, which emphasizes the willingness of employees to accept that managers have legitimate authority to act. In other words, the organizational goals will be accomplished and authority will be accepted when workers feel satisfied that their individual needs are being met. Accordingly four factors that affects this willingness includes; ○ Clarity in communication to the employees ○ Consistency of what is communicated with the organization’s purposes ○ Consistency in action with the needs and desires of the employees ○ Feeling of mental and physical ability in carry out the order ● Henri Fayol suggested that all managers perform five main functions that are plan, organize, command, coordinate and control. Accordingly he proposed 14 principles of management: ○ Division of work ○ Authority and Responsibility ○ Discipline ○ Unity of Command ○ Unity of Direction ○ Organizational needs over individual needs ○ Fair payments for efforts ○ Centralization ○ Chain of command ○ A place for everything and everyone ○ Treat people equally ○ Limited turnover ○ Encourage initiatives ○ Promote harmony ● Max Weber observed management and organizational behaviour from a structural perspective and described organizational activity based on authority relations. He proposed: Bureaucracy, a system characterized by division of labour, a clearly defined hierarchy, detailed rules and regulations, and impersonality as the ideal type of organization. ● Mary Parker Follet, a social philosopher, proposed more people oriented ideas and argued that organizations should be based on a group ethic rather than on individualism. She believed in corporate social responsibility, and profit sharing with employees, criticized greed, stood with ethics, and encouraged unions. Proposed four principles of coordination: ○ Early Stage ○ Continuity ○ Direct Contacts ○ Reciprocal Relations Human Relations Movement ● Hawthorne Studies by Elton Mayo studies happened in the late 1920s and early 1930s, in Western Electric Company to find out ways to improve productivity. As a result, the concept of Hawthorne effect was discovered which suggests that better lighting increased productivity and also when workers see that people show concern for productivity rises more. ● Dale Carnegie emphasized on the importance of winning people’s corporation to succeed and gave few important advices to follow: ○ Make others feel important through a sincere appreciation of their efforts Commented [1]: Weber's ideal bureaucracy 1. Job Specialization. Jobs are broken down into simple, routine, and well-defined tasks. 2. Authority Hierarchy. Offices or positions are organized in a hierarchy, each lower one being controlled and supervised by a higher one. 3. Formal Selection. All organizational members are to be selected on the basis of technical qualifications demonstrated by training, education, or formal examination. 4. Formal Rules and Regulations. To ensure uniformity and to regulate the actions of employees, managers must depend heavily on formal organizational rules. 5. Impersonality. Rules and controls are applied uniformly, avoiding involvement with personalities and personal preferences of employees. 6. Career Orientation. Managers are professional officials rather than owners of the units they manage. They work for fixed salaries and pursue their careers within the organization ○ Strive to make a good first impression ○ Win people to your way of thinking by letting others do the talking, being sympathetic, and ‘never telling a man he is wrong’ ○ Change people by praising their good traits and giving the offender the opportunity to save face ● Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs ● Douglas McGregor proposed theory X and Theory Y. According to theory X people have no ambition, disliked work and tend to avoid responsibility. As a result they needed to be closely monitored to ensure efficient work. On the other hand theory Y suggests that people can exercise self-direction, accept responsibility and consider work to be as natural as rest or play. He believed that theory Y best captured the true nature of workers. Behavioural Era ● The first personnel office with the growth of trade unionism. ● Hugo Munsterberg used the concept of Industrial Psychology in his book Psychology and Industrial Efficiency (1913). He found a link between scientific management and industrial psychology. He suggested use of psychological tests to improve employee selection, and learning theories in the development of training methods. He also suggested studying human behavior to understand what techniques are most effective to motivate workers. ● The Wagner Act was passed in 1935 to give a relief to the effects of depression. The act recognized unions as the authorized representatives of workers and gave power to the unions to collectively represent interests of members. As a result, efforts were made to improve working conditions, and managers began to seek better relations with the workforce. Considered as the Magna Carta of labour as the act gave freedom to labourers. Major Fields in Industrial Psychology Arnold, Robertson & Cooper (1991, p. 32) suggested 12 different areas in which they work. Selection, Assessment and Personnel Psychology a. It deals with job analysis, tests, employment interviews, e-selection and training, supervision of people in business and industrial settings and human factors for all types of jobs by a variety of methods. Training b. It determines training needs and evolves training programmes to meet the needs. Performance Appraisal c. It defines and measures job performance, performance appraisal, and provides training in appraisal techniques. Organisational Change d. It pertains to the analysis of the organisation for change due introduction of new technologies and processes. Ergonomics and Human Engineering e. It involves the application of human performance principles, models, measurements, and techniques to systems design. The goal of engineering is to optimise systems' performance by taking human physical and cognitive capabilities and limitations into con-sideration during design. Vocational Choice and Counseling f. Analysis of a person's abilities, interests and values and their translation into occupational terms. Interpersonal Skills g. It involves identification and development of skills such as.leadership, assertive-ness, team work etc. Occupational Safety and Health h. It examines the cause of accidents and the measures to reduce their frequencies. Managerial Psychology i. It is concerned with problems of management in industry. Work Design/Consumer Psychology j. It studies the numerous factors of relationship between an organisation that provides goal or services and the individuals who are the recipients thereof—the consumer. Organisational Psychology k. It deals with total functioning of a company, or any type of organisation for that matter, including attitude survey. Stress and Wellbeing at Work l. It involves investigation of factors that lead to stress at work and unemployment. Lowenberg and Connard (1998) suggest slightly different areas based on a survey of the working American psychologists: ● Organisational Development and Change: Studying structure, its roles, and its impact on productivity and satisfaction. ● Individual Development: Training, performance management, mentoring, managing stress, and coun-selling. ● Performance Evaluation and Selection: Developing assessment tools for selection and performance evaluation. ● Preparing and Presenting Results ● Compensation and Benefits: Developing criteria and measuring accomplishments. UNIT 2 - Individual in Workplace Personality Definition ● According to Gordon Allport, personality is “the dynamic organization within the individual of those psychophysical systems that determine his unique adjustments to his environment.” ● In simple terms, personality is the sum total of ways in which an individual reacts to and interacts with others i.e the measurable traits an individual exhibits. Measuring Personality ● The most common means of measuring personality is through self-report surveys, with which individuals evaluate themselves on a series of factors ● Though self-report measures work well when well constructed, one weakness is that the respondent might lie or practice impression management to create a good impression. ● When people know their personality scores are going to be used for hiring decisions, they rate themselves as about half a standard deviation more conscientious and emotionally stable than if they are taking the test just to learn more about themselves. ● Another problem is accuracy. A perfectly good candidate could have been in a bad mood when taking the survey, and that will make the scores less accurate. ● Observer-ratings surveys provide an independent assessment of personality. ● Here, a co-worker or another observer does the rating (sometimes with the subject’s knowledge and sometimes not). ● Though the results of self-report surveys and observer-ratings surveys are strongly correlated, research suggests observer-ratings surveys are a better predictor of success on the job ● An analysis of a large number of observer-reported personality studies shows that a combination of self-report and observer-reports predicts performance better than any one type of information. ● The implication is clear: use both observer ratings and self-report ratings of personality when making important employment decisions. Personality Determinants ● An early debate in personality research centered on whether an individual’s personality was the result of heredity or of environment. ● It appears to be a result of both. However, it might surprise you that research tends to support the importance of heredity over the environment. ● Heredity refers to factors determined at conception. ● Physical stature, facial attractiveness, gender, temperament, muscle composition and reflexes, energy level, and biological rhythms are generally considered to be either completely or substantially influenced by who your parents are—that is, by their biological, physiological, and inherent psychological makeup. ● The heredity approach argues that the ultimate explanation of an individual’s personality is the molecular structure of the genes, located in the chromosomes. ● Interestingly, twin studies have suggested parents don’t add much to our personality development. ● The personalities of identical twins raised in different households are more similar to each other than to the personalities of siblings with whom the twins were raised. Ironically, the most important contribution our parents may make to our personalities is giving us their genes! ● Early work on the structure of personality tried to identify and label enduring characteristics that describe an individual’s behavior, including shy, aggressive, submissive, lazy, ambitious, loyal, and timid. ● When someone exhibits these characteristics in a large number of situations, we call them personality traits of that person. The more consistent the characteristic over time, and the more frequently it occurs in diverse situations, the more important that trait is in describing the individual. ● Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the Big Five Model, are now the dominant frameworks for identifying and classifying personality traits. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator ● The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is the most widely used personality assessment instrument in the world. ● It is a 100-question personality test that asks people how they usually feel or act in particular situations. ● Respondents are classified as extraverted or introverted (E or I), sensing or intuitive (S or N), thinking or feeling (T or F), and judging or perceiving (J or P). These terms are defined as follows: ○ Extraverted (E) versus Introverted (I). Extraverted individuals are outgoing, sociable, and assertive. Introverts are quiet and shy. ○ Sensing (S) versus Intuitive (N). Sensing types are practical and prefer routine and order. They focus on details. Intuitives rely on unconscious processes and look at the “big picture.” ○ Thinking (T) versus Feeling (F). Thinking types use reason and logic to handle problems. Feeling types rely on their personal values and emotions. ○ Judging (J) versus Perceiving (P). Judging types want control and prefer their world to be ordered and structured. Perceiving types are flexible and spontaneous. ● These classifications together describe 16 personality types, identifying every person by one trait from each of the four pairs. ● For example, Introverted/Intuitive/Thinking/Judging people (INTJs) are visionaries with original minds and great drive. They are skeptical, critical, independent, determined, and often stubborn. ESTJs are organizers. They are realistic, logical, analytical, and decisive and have a natural head for business or mechanics. The ENTP type is a conceptualizer, innovative, individualistic, versatile, and attracted to entrepreneurial ideas. This person tends to be resourceful in solving challenging problems but may neglect routine assignments. Drawback of MBTI ● It forces a person into one type or another; that is, you’re either introverted or extraverted. There is no in-between, though in reality people can be both extraverted and introverted to some degree. ● The best we can say is that the MBTI can be a valuable tool for increasing self-awareness and providing career guidance. But because results tend to be unrelated to job performance, managers probably shouldn’t use it as a selection test for job candidates. The Big Five Personality Model ● Big Five Model—that five basic dimensions underlie all others and encompass most of the significant variation in human personality. Moreover, test scores of these traits do a very good job of predicting how people behave in a variety of real-life situations. ● The following are the Big Five factors: ○ Extraversion. The extraversion dimension captures our comfort level with relationships. Extraverts tend to be gregarious, assertive, and sociable. Introverts tend to be reserved, timid, and quiet. ○ Agreeableness. The agreeableness dimension refers to an individual’s propensity to defer to others. Highly agreeable people are cooperative, warm, and trusting. People who score low on agreeableness are cold, disagreeable, and antagonistic. ○ Conscientiousness. The conscientiousness dimension is a measure of reliability. A highly conscientious person is responsible, organized, dependable, and persistent. Those who score low on this dimension are easily distracted, disorganized, and unreliable. ○ Emotional stability. The emotional stability dimension—often labeled by its converse, neuroticism—taps a person’s ability to withstand stress. People with positive emotional stability tend to be calm, self-confident, and secure. Those with high negative scores tend to be nervous, anxious, depressed, and insecure. ○ Openness to experience. The openness to experience dimension addresses range of interests and fascination with novelty. Extremely open people are creative, curious, and artistically sensitive. Those at the other end of the category are conventional and find comfort in the familiar. For more information refer to page 136-139 in Robins. Other Traits Relevant to Organisational Behaviour ● Core self-evaluation ○ People who have positive core self-evaluations like themselves and see themselves as effective, capable, and in control of their environment. Those with negative core self-evaluations tend to dislike themselves, question their capabilities, and view themselves as powerless over their environment. ○ People with positive core self-evaluations perform better than others because they set more ambitious goals, are more committed to their goals, and persist longer in attempting to reach these goals. ■ One study of life insurance agents found core self-evaluations were critical predictors of performance. ○ However, an overly positive self-evaluation can be detrimental. ■ One study of Fortune 500 CEOs showed that many such individuals are overconfident, and their perceived infallibility often causes them to make bad decisions. ● Machiavellianism ○ The personality characteristic of Machiavellianism (often abbreviated Mach) is named after Niccolo Machiavelli, who wrote in the sixteenth century on how to gain and use power. ○ An individual high in Machiavellianism is pragmatic, maintains emotional distance, and believes ends can justify means. ○ A considerable amount of research has found high Machs manipulate more, win more, are persuaded less, and persuade others more than do low Machs. 35 They like their jobs less, are more stressed by their work, and engage in more deviant work behaviors ○ Yet high-Mach outcomes are moderated by situational factors. High Machs flourish: ■ When they interact face to face with others rather than indirectly ■ When the situation has minimal rules and regulations, allowing latitude for improvisation ■ When emotional involvement with details irrelevant to winning distracts low Machs. ● Narcissism ○ In psychology, narcissism describes a person who has a grandiose sense of self-importance, requires excessive admiration, has a sense of entitlement, and is arrogant ○ Despite having some advantages, most evidence suggests that narcissism is undesirable. ■ A study found that while narcissists thought they were better leaders than their colleagues, their supervisors actually rated them as worse. ○ Because narcissists often want to gain the admiration of others and receive affirmation of their superiority, they tend to “talk down” to those who threaten them, treating others as if they were inferior. ○ Narcissists also tend to be selfish and exploitive and believe others exist for their benefit. ○ Their bosses rate them as less effective at their jobs than others, particularly when it comes to helping people. ○ Subsequent research using data compiled over 100 years has shown that narcissistic CEOs of baseball organizations tend to generate higher levels of manager turnover, although curiously, members of external organizations see them as more influential. ● Proactive Personality ○ Those with a proactive personality identify opportunities, show initiative, take action, and persevere until meaningful change occurs, compared to others who passively react to situations. ○ They are more likely than others to be seen as leaders and to act as change agents. ○ Proactive individuals are more likely to be satisfied with work and help others more with their tasks, largely because they build more relationships with others ○ Proactives are also more likely to challenge the status quo or voice their displeasure when situations aren’t to their liking. However, they are also more likely to leave an organization to start their own business. ● Other-orientation ○ This is a personality trait that reflects the extent to which decisions are affected by social influences and concerns vs. our own well-being and outcomes ○ Those who are other-oriented feel more obligated to help others who have helped them (pay me back), whereas those who are more self-oriented will help others when they expect to be helped in the future (pay me forward). ○ Employees high in other-orientation also exert especially high levels of effort when engaged in helping work or prosocial behavior ○ However, research is still needed to clarify this emerging construct and its relationship with agreeableness. Motivation ● Motivation can be defined as a process that accounts for an individual’s intensity, direction and persistence of efforts towards reaching a goal. ● Intensity refers to how hard a person is trying. ● Direction refers to the quality of effort, whether the intense drive is bringing the person closer to his workplace goals or not. ● Persistence: for how long is the person willing to try and work hard on a reaching a goal. ● Motivated individuals stay with a task long enough to attain their goals. Theories of motivation Hierarchy of needs: Maslow ● Within every individual lies a hierarchy of 5 needs. The higher order needs cannot be reached if the lower order needs are not met. ● When a lower order need is satisfied the person moves to a higher order need. No need can be completely satisfied so a substantial fulfilment of a need no longer motivates the individual. ● In order to motivate a person you must identify which level of hierarchy of need is the person on: focus on satisfying that need. ● Physiological and safety are the lower order needs while the other three are higher order needs ● Lower order needs are satisfied by the organisation (Pay, Wages, unions, contracts, tenure etc) whereas the higher order needs are satisfied internally by the person himself. Physiological needs: ○ Hunger, Thirst, Shelter, Sex and other bodily needs. Safety needs ○ Security and protection from emotional and physical harm. Social needs ○ Acceptance, belongingness, affection and friendship. Esteem needs ○ Internal factors: self respect, autonomy and achievement. ○ External factors: status, recognition, and attention. Self actualisation ○ Reaching one’s full potential. ○ Self fulfilment. Two Factor Theory: Frederick Herzberg ● A theory that links intrinsic factors (advancement, achievement, recognition, responsibility) to job satisfaction while associating extrinsic factors (supervision, pay, company policy and working conditions) to dissatisfaction. ● Also known as the Motivation-Hygiene Theory. ● He believed that one’s attitude towards work can determine their level of success or failure. He asked people to describe in detail, situation in which they feel exceptionally good or bad about their work. Their responses were then tabulated and categorised. ● This suggested to Herzberg that the opposite of satisfaction is not dissatisfaction. Removing dissatisfying characteristics from a job does not necessarily make it satisfying. ● There exists a dual continuum. The opposite of satisfaction is “No Satisfaction” and the opposite of Dissatisfaction “No Dissatisfaction” ● The factors leading to satisfaction are different from the factors leading to dissatisfaction and hence the managers who try to remove these dissatisfying factors are just placating the employees and are not motivating them. ● Herzberg characterised the situations surrounding work like pay, supervision, company policies, working conditions etc as HYGIENE factors. ● When these factors are adequate people will neither be dissatisfied nor satisfied. ● To motivate people the manager must emphasise on factors associated with the work itself or outcomes directly driven from it like: Promotional opportunities, personal growth, recognition, responsibility and achievement. Atkinson & McClelland's Need for Achievement Theory: McClelland’s theory of needs was developed by David McClelland and his associates. It looks at three needs: Achievement ● Need for achievement (nAch) is the drive to excel, to achieve in relationship to a set of standards. Authority ● Need for power (nPow) is the need to make others behave in a way they would not have otherwise. Affiliation ● Need for affiliation (nAff) is the desire for friendly and close interpersonal relationships. Alderfer’s ERG theory Alderfer’s ERG theory suggests that there are three groups of core needs: existence (E), relatedness (R), and growth (G)—hence the acronym ERG. These groups align with Maslow’s levels of physiological needs, social needs, and self-actualization needs, respectively. 1. Existence needs concern our basic material requirements for living. These include what Maslow categorized as physiological needs (such as air, food, water, and shelter) and safety-related needs (such as health, secure employment, and property). 2. Relatedness needs have to do with the importance of maintaining interpersonal relationships. These needs are based in social interactions with others and align with Maslow’s levels of love/belonging-related needs (such as friendship, family, and sexual intimacy) and esteemrelated needs (gaining the respect of others). 3. Finally, growth needs describe our intrinsic desire for personal development. These needs align with the other portion of Maslow’s esteem-related needs (self-esteem, self-confidence, and achievement) and self-actualization needs (such as morality, creativity, problem-solving, and discovery). Alderfer proposed that when a certain category of needs isn’t being met, people will redouble their efforts to fulfill needs in a lower category. For example, if someone’s self-esteem is suffering, he or she will invest more effort in the relatedness category of needs. Types of motivation Intrinsic motivation ○ A person will be motivated to perform a task if the task is personally rewarding. ○ Essentially it means performing an activity for its own sake and not because of a desire for an external reward. ○ Some research suggests that providing an external reward for such a task might reduce the motivation of the person to perform it. Extrinsic Motivation ○ Occurs when one engages in an activity to earn a reward or avoid punishment. ○ One does not engage in an activity for the sake of that activity but because they want to get something in return or to avoid an unpleasant situation. Job Satisfaction ● Job satisfaction is a positive feeling about one’s job resulting from an evaluation of its characteristics. ● A collection of positive or negative feelings that an individual has towards his job, co-workers or the work environment in general. It involves cognitive, affective and evaluative reactions. ● The employee’s job satisfaction depends on the a complex summation of a number of discreet job elements (like work place relationships, rules etc.). ● To measure job satisfaction two common tools are used: ● A single global rating: “All things considered how satisfied are you with your job?” (1-5 Likert scale ranging from highly satisfied to highly dissatisfied). ● A summation of score made up of a number of job facets.: Identifies key facets of each job and asks the employee’s feelings about them all. (present pay, promotion opportunities, etc.). Scores are tabulated and a total score of job satisfaction is created. ● Job engagement: The employees go out of their way and their assigned roles and contribute a little more to help the organisation reach its goals. ● Employee satisfaction: the emotional connect one has with the job. It refers to both the positive and the negative feelings associated with one’s job. ● Employee engagement: the amount of passion one has for his job. A passionate employee will work hard and think about the benefit of his organisation as well. ● Any organisation expects its employees to be engaged with the company. Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction ● Individual factors-personality traits, age, education, marital status, intelligence, abilities ● Social factors: relationship with co-workers, group work, informal organisations ● Cultural Factors: attitudes beliefs and values ● Organisational Factors: nature, size, structure of the organisation, policies, employee relations. ● Other factors: Work itself, pay, supervision, Promotions, Working conditions. Results And Impact Of Job Satisfaction ● Results of Job Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction: The EVLN framework ○ Exit ■ Active and destructive. ■ Dissatisfaction is shown by behaviour directed towards leaving the organisation, actively looking for new positions and resigning. ○ Voice ■ Active and Constructive. ■ Dissatisfaction is expressed by giving active responses that may help improve the conditions, discussing the problems with the superiors and some form of union activity. ○ Neglect ■ Passive and destructive. ■ Passively allowing the conditions to worsen. ■ Chronic absenteeism, lateness, reduced efforts, and increased error rates. ■ Low organisation citizenship ○ Loyalty ■ Passive and Constructive. ■ Passively and optimistically waiting for the conditions to improve, speaking up for the organisation in the face of external criticism. ■ Trusting the organisation and the management to do the right thing. ● Impact of Job Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction ○ Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: ■ A happy worker is a productive worker. ■ Research suggests that organisations with more satisfied workers are more effective than the ones with fewer satisfied workers. ○ Job Satisfaction and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) ■ Satisfied employees will talk positively about their organisation, help others and go beyond what is expected of them and are more willing to go beyond the call of duty because they would like to reciprocate the positive experience. ■ If you are not happy or think that the treatment or pay given to you is unfair you will be dissatisfied with the job. ■ If you trust your organisation you will actively work towards its goals. ○ Job Satisfaction and Customer Satisfaction ■ Satisfied employees are usually friendly, upbeat and responsive: customer friendly. ■ Satisfied employees are less likely to quit and hence the customer meets familiar faces everytime they do business with the company. ■ A dissatisfied customer can reduce employee satisfaction. ■ Employees that have to deal with rude, demanding and inconsiderate customers on a day to day basis are often dissatisfied. ○ Job Satisfaction and Absenteeism ■ If you are satisfied you will come to work. ■ However other factors like how liberal is your organisation at granting leaves also plays a role. ■ It the organisation is liberal even the highly satisfied people will be motivated to take leaves. ○ Job satisfaction and Turnover ■ If you are satisfied you will not quit. ■ Level of satisfaction is less important in predicting turnover for superior performers because organisations typically makes considerable efforts to keep these people by giving good pay raises, recognition, promotional opportunities etc, which doesn’t happen for inferior performers as very few attempts are made by the organisation to retain them. ○ Job Satisfaction and Workplace Deviance ■ Job dissatisfaction predicts a lot of specific behaviours, including unionization attempts, substance abuse, stealing at work, undue socialising, and tardiness. Measures of Job Satisfaction Advantages of Using Job Satisfaction Scales ● Job satisfaction is usually measured with interviews or questionnaires administered to the job incumbents in question. ● Spector (1997) has listed several advantages of using the existing job satisfaction scales for measuring job satisfaction. These are: ○ Many of the available scales cover major facets of satisfaction. ○ Most existing scales have been used a sufficient number of times to provide norms; comparison with norms can help in interpretation of results from a given organisation. ○ Many existing scales have been shown to exhibit acceptable levels of reliability. ○ Their use in research provides good evidence for construct validity The Job Satisfaction Survey ● The Job Satisfaction Survey assesses nine facets of job satisfaction, namely: ○ Pay ○ Promotion ○ Supervision ○ Fringe benefits ○ Contingent rewards ○ Operating conditions ○ Co-workers ○ Nature of work, and communication. ● The scale contains thirty six items and uses a summated rating scale format. Each of the nine facet subscales contain four items, and a total satisfaction score can be computed by combining all the items. Job Descriptive Index ● The Job Descriptive Index (Smith, Kendall, & Hulin, 1969) is perhaps the most popular scale for measuring job satisfaction. ● The entire scale contains seventy two items with either nine or eighteen items per scale. ● The facets measured by the scale are as follows: ○ Work ■ Satisfaction with work and its attributes include opportunities for creativity and task variety and ability to increase one’s knowledge, responsibility, work volume, autonomy, and complexity. ■ Satisfying work appears to be one that can be accomplished and is intrinsically challenging (routine work) ○ Pay ■ Satisfaction with work based on the perceived difference between actual pay and expected pay, which, in turn, is based on perceived inputs and outputs of the job and the pay of other comparable employees. ■ The personal financial situation of the employee, the economy, and the amount of pay an employee has received previously also influence satisfaction (income adequate for normal expenditure). ○ Promotion ■ Satisfaction with promotion is based on the employee’s satisfaction with the company’s promotion policy and the administration of that policy. ■ It is thought to be a function of frequency of promotions, the importance of promotions, and the desirability of promotions (good opportunity for promotion). ○ Supervision ■ Satisfaction with supervision is based on an employee’s satisfaction with his or her supervisor’s knowledge and competence and the supervisor’s warm, interpersonal orientation (hard to please) ○ People on the Job ■ Satisfaction with the people on the job, which is often called the co-worker facet, refers to satisfaction with one’s fellow employees or clients. ■ Separate facets may be created using the same items to measure satisfaction with people, such as staff, and satisfaction with clients (helpfulness). ○ Job in General ■ Satisfaction with the job in general reflects the employee’s global long term evaluation of his or her job. ■ It subsumes the evaluation of the above five facets and the interactions, as well as the employee’s evaluation of other long term situational and individual factors (better than most). Job Diagnostic Survey ● Hackman and Oldham (1980) developed a scale, called the Job Diagnostic Survey, to measure each one of the variables of their model. ● An ‘@’ next to a facet signifies that the response format for items in these facets is a seven point scale ranging from extremely dissatisfied to extremely satisfied. ● An ‘*’ next to a facet signifies that the response format for items in these facets is a seven point scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly ● The facets measured by the survey and their descriptions are as follows: ○ Job Security@ ■ The amount of Job Security I have ■ How secure things look for me in the future of the organisation ○ Pay@ ■ The amount of pay and fringe benefits I receive ■ The degree to which I am fairly paid for what I contribute to the organisation ○ Co-workers* ■ The people with whom I talk and with whom I work ■ The chances to get to know other people while on the job ■ The chance to help other people while at work ○ Supervision* ■ The degree of respect and fair treatment I receive from my supervisor ■ The amount of support and guidance I receive from my supervisor ■ The overall quality of supervision I receive in my work ○ General @ ■ How satisfied I am with my job ■ The kind of work I do in this job ■ The frequency with which I think of quitting my job ( reverse scoring) ■ How satisfied most of my co-workers are with their jobs ■ The frequency with which my co-workers think of quitting their jobs ○ Growth @ ■ The amount of personal growth and development I get in doing my job ■ The feeling of worthwhile accomplishment I get from doing my job ■ The amount of independent thought and action I can exercise in my job ■ The amount of challenge in my job Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire ● The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) is designed to measure an employee’s satisfaction with his/her job. ● Three forms are available: two long forms (1977 version and 1967 version) and a short form. ● The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire provides more specific information on the aspects of a job that an individual finds rewarding than the general measures of job satisfaction. ● It is useful in exploring client vocational needs, counseling follow-up studies, and generating information about the reinforcers in jobs. ● The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire is a paper and pencil inventory of the degree to which vocational needs and values are satisfied in a job. I ● it can be administered to groups or individuals, and is appropriate for use with individuals who can read at the fifth grade level or higher. ● All three forms are gender neutral. ● Instructions for the administration of the questionnaire are given in the booklet. ● The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Long Form requires 15 to 20 minutes to complete. The Short Form requires about 5 minutes. Unless the 15 to 20 minutes required for the Long Form is impractical, it is strongly recommended that Long Form Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire ○ There are two versions of the long form MSQ, a 1977 version and a 1967 version. ○ The 1977 version, which was originally copyrighted in 1963, uses the following five response choices: ■ 1. Very Satisfied 2. Satisfied 3. ‘N’ (Neither Satisfied nor Dissatisfied) 4. Dissatisfied 5. Very Dissatisfied Normative data for the twenty one ○ Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire scales for twenty five representative occupations, plus employed disabled and employed non-disabled workers, are in the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire manual. ○ A ceiling effect obtained with the rating scale used in the 1977 version tends to result in most scale score distributions being markedly negatively skewed; mostresponses alternate between ‘Satisfied’ and ‘Very Satisfied.’ ○ The 1967 version adjusts for this ceiling effect by using the following five response categories: ■ 1. Not Satisfied 2. Somewhat Satisfied 3. Satisfied 4. Very Satisfied 5. Extremely Satisfied ○ This revised rating scale resulted in distributions that tend to be more symmetrically distributed around the ‘satisfied’ category, with larger item variance. ■ Limited normative data are provided in the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire manual for the 1967 version. ■ For this reason the 1967 version of the questionnaire is best used where normative data is not required, such as prediction studies or withinorganisation comparisons, where external norms are not necessary. Short Form Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire ○ This form consists of twenty items from the long form questionnaire that best represent each of the twenty scales. ○ Factor analysis of the twenty items resulted in two factors: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Satisfaction. ○ Scores on these two factors plus a General Satisfaction score may be obtained. The short-form Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire uses the same response ○ Questionnaire uses the same response categories used in the 1977 long form. Michigan Organisational Assessment Questionnaire Subscale ● The Michigan Organisational Assessment Questionnaire Subscale contains three overall satisfaction sub-scales (Cammann et al. 1979). ● The scale is simple and short, which makes it ideal for use in questionnaires that contain many scales. ● Reliability of tests has been reported as .77. ● For each item there are seven response choices: Strongly disagree; Disagree; Slightly Disagree; Neither agree or disagree; Slightly agree; Agree; Strongly agree. ● The items are totalled to yield overall job satisfaction score. ● Validity evidence for the scale is provided by research in which it has been correlated with many other work variables Unit 3 Planning and Development of human resources Job Analysis Definition Job analysis is the process of studying and collection information about the operations and responsibilities of a specific job. The immediate outcome of job analysis is job description and job specifications. Job analysis involves: ● A systematic study of the job. ● Analysis of the nature of the job. ● Provide inputs to select an appropriate person for the job. ● With the right set of skills, knowledge, experience, abilities and behaviour. Purpose The purpose of job analysis is to identify the specific needs of a job and hire a person who can do maximum justice to the job with his specific skill set and knowledge base. 1. Job description: It involves job information, job summaries, duties, responsibilities, standards and specifications. 2. Job classification: Arrangement of jobs into families, classes and groups based on the classification schemes. 3. Job evaluation: Establishing the relative worth of a job using internal and external reference to set remuneration. 4. Personnel requirement and specif ication: Listing out the traits and characteristic that are required on the part of the employee for the accomplishment of the tasks. 5. Performance appraisal: Factors and dimensions that should be considered for performance appraisals. 6. Worker training: Worker characteristics required for the task. 7. Worker mobility: Career development for the employee-scope for moving in and out of various positions, jobs and occupation. 8. Efficiency and safety: Designing the safest and efficient work procedures, layouts and standards. 9. Manpower and work force planning: Identifying the number of people required to do the job at the desired pace and efficiency. Keeping in mind the self actualisation of the employees: utilising their skills and talents to the fullest. 10. Legal and quasi-legal requirements: Framing work keeping in mind the legal set up and requirements. Keeping in mind the labour unions and the industry’s guidelines. Types Work or task oriented job analysis ○ This approach begins with the statement of the task that the worker will have to perform, the machinery used and the work context. Worker-oriented job analysis ○ This approach focuses on the attributes and characteristics of the employee that are necessary to accomplish the task that define the job. Process 1. Behaviour description: The kind of behaviour an employee actually demonstrates while doing a task. 2. Behaviour requirements: The kind of behaviour an employee should demonstrate while doing a task. 3. Ability requirements: Human traits and personal abilities required to do a task. 4. Task characteristics: Focuses on task analysis in terms of the objective characteristic of the task in hand. After selecting one of the above mentioned approach the process of job analysis comes into motion. 1. Strategic choices: Make decisions about how the job analysis has to be done. The level of depth and detail, past oriented or future oriented, schedules and frequencies and the source of job data. 2. Collection of background data: The analyst then gathers information about the job itself, number of vacancies, current or previous job descriptions, division of work etc. 3. Conduct ‘needs research’ selecting representative jobs: Recognize the basic need of the job. 4. Establish priorities: Priority of order in which information will be collected. 5. Collection of job analysis data: Analyses the people who are currently doing the job, he then develops job specifications, job description and employee specification. 6. Drafting of job analysis data: Observations and analysis are written down, recruitment or training programme begin keeping in mind the analysis that has been made. 7. Sources of job data: Human (employees, managers, analysts, job experts, manufacturers) and non human ( existing job descriptions, manual records, equipment maintenance records, blue prints, training manuals, pop literature etc) Methods 1. Interview 2. Observation 3. Questionnaire 4. Diary or logbook of job incumbent 5. Checklist 6. Technical conference Recent Developments 1. Electronic process monitoring 2. Role analysis 3. Cognitive Work analysis 4. Competency modelling 5. Personality based job analysis 6. Strategic job analysis Recruitment and Selection Nature and objectives ● Recruitment refers to the discovery of potential candidates for a specific job. ○ It links the people who are offering a job and the people seeking a job. ● The purpose of recruitment is to locate sources of manpower to meet job requirements and job specifications. ● Recruitment can be seen as positive since it encourages potential employees to apply for the job. Selection on the other hand is negative as it rejects a lot of potential candidates and hires on the best of the lot. Purpose The purposes of recruitment are as follows: ● Attract and empower an ever increasing number of applicants to apply in the organization. ● Build positive impression of the recruitment process. ● Create a talent pool of candidates to enable the selection of best candidates for the organization. ● To attract and engage people it needs to achieve its overall organizational objectives. ● Increase the pool of job candidates at minimum cost ● Recruit the right people who will fit into the organization's culture and contribute to the organization's goals. ● Determine Current and future requirements of the organization in conjunction with its personnel planning and job analysis activities. ● It helps upwards the achievement rate of the choice process by diminishing the number of unmistakably underqualified or overqualified work candidates. ● It helps decrease the likelihood that activity candidates once enlisted and chose will leave the organization after a brief time frame. ● Meet the organizations lawful and social commitments with respect to the synthesis of its workforce. ● Begin identifying and preparing potential job applicants who will be appropriate candidates. ● Increment organization and individual effectiveness of different selecting systems temporarily and long haul. ● Evaluate the effectiveness of various recruiting techniques and sources for all types of job applicants. Sources Internal Internal sources refers to the present workforce that an organisation possesses. In case of a vacancy these employees are mobilised or promoted to handle other responsibilities. These may also include workers who had been laid off or the employees who had quit. Merits ■ Saves time. ■ Reduced cost of recruitment. ■ Improves morale of the employees- they are preferred over others. ■ Improves the loyalty of the employees. ■ Lead less training since they are already acquainted with the set up. ■ Can be relied on. ■ The employer can make the best choice since they have records of all the employees and their progress. Demerits ■ Restricts inbreeding and discourages new blood from entering the organisation. ■ Employer bias may play a role. ■ Promotion is usually based on seniority and hence merit may be ignored. ■ Since the employee has no new knowledge set, this procedure may not be useful for creative or rapidly changing fields. External External Sources are sources that were previously not a part of the organisation. This category may include: 1. New labour force: people who have just graduated- inexperienced. 2. The unemployed: people who have been looking for jobs for a long time, may be skilled and experienced. 3. People who have retired from their jobs. 4. Other labour forces like married women and minority groups who were not previously employed. Merits ■ A large number of applicants may be available. ■ The employer has more options. ■ A new employee comes with new ideas and creativity which might be helpful for certain fields. ■ Proves economical in the long run. Demerits ■ The possibility of brain drain is always there. Methods of External Recruitment ● Direct Recruitment, Walk In/Write In ○ Direct recruitment is an important method and source of recruitment. ○ Vacancies are advertised and recruitment done at the factory gate. ○ This practice is generally followed for vacancies requiring low skills, or for unskilled workers. ● Casual Callers or Unsolicited Applications ○ The organisations which have a reputation in the market and are considered good employers attract a steady flow of unsolicited applicants. ○ This serves as a valuable source of manpower. ○ The major advantage of this source is that it limits the expenditure towards cost of recruitment. ● Advertisement in Media other than Telecasting ○ Advertisements in newspapers, trade and professional journals are generally used to attract potential skilled employees or an employees with special abilities. ○ The higher the position in the organisation and more specialised the skills sought, the more widely dispersed the advertisement is likely to be. ○ An advertisements, including those over the internet, should include the under mentioned: ■ Job content ■ Realistic description of working conditions ■ Location of the job ■ Compensation, including benefits ■ Skills and abilities required ■ To whom should the application be submitted ● Telecasting ○ Telecasting is an important medium for attracting attention of the viewers. ○ It can give visual display of the conditions prevalent. ○ However, it is not very popular with companies for recruiting purposes due to its high cost, advertisement may be missed out by candidates, etc ● Employment Agencies and Head Hunters ○ Government run employment exchanges are a source of recruitment. In some cases, government has made it mandatory for notification of vacancies to the employment exchange. ○ Today, there are large number of agencies in private sector that specialise in placement services. These agencies charge either the employer or the employee for their services. ○ These are most effective when an organisation has difficulty in finding or searching for a potential candidate, or when the particular skill is scarce. These concerns also maintain a data bank of persons with different skills and abilities. ○ ABC Concultants, A F Ferguson, Mantec Consultants are few of the concerns specialising in placements. ● Campus Recruitment ○ Today, due to complexity of jobs, large number of companies maintain close liaison with universities, colleges, and technical institutes to meet their recruitment needs. ○ In this method, the process begins much before the academic session ends. ■ Normally, a presentation by the company is made giving the background of the company and what they are seeking. ■ Thereafter, the placement officer of the institute coordinates with the recruiter and pre-placement talks are initiated. ■ Then, the candidates are encouraged to apply for selection. ○ This method has proved its effectiveness. ■ It enables companies to build a pool of applicants to choose from. ■ This also helps companies to subsequently mould the applicants selected as they are young ● Voluntary Organisations ○ Some voluntary organisations also help in placement. They basically deal with handicapped, widows, retired personnel, etc. ● Professional organisations or Guilds ○ Professional organisations are also a source of recruitment. ○ However, these are restricted to people belonging to a particular profession. ○ A perspective employer can approach the organisation if he is seeking a person with a specific qualification ● Professional Teams ○ These are temporary groups which come together for accomplishment of a specific job or assignment. ○ Normally these are professional freelancers. ○ This scheme has not yet picked up in India but is gaining popularity Steps Involved 1. Planning: Identifying vacancy, job description, job specification, job evaluation, job analysis. 2. Strategy Development: How to interview, geographical area, recruitment sources, setting up a board, analysing HR strategy, et cetera. 3. Searching: Source activation (“ Vacancy Available”) selling (spreading the message), internal sourcing, external sourcing. 4. Screening: Filtering qualified candidates, reviewing resumes, interviews, identifying top candidates. 5. Evaluation and control: Evaluating the strategy, costs of recruitment (Salary, advertisements, administrative expenses, overtime cost while the vacancies are being filled, time spent on creating job description etc) Process Selection process involves securing relevant information about a potential candidate. The purpose of the selection process is to hire a person who is best suited for the job in terms of qualifications, skills and knowledge. 1. Reception of application 2. Preliminary interview 3. Application blank 4. Psychological tests 5. Interview 6. Background information 7. Final selection by interviews 8. Physical examination 9. Placement Performance Management Performance management systems are among the most important human resource practices and also a comprehensively discussed topic. Your instructor will measure your performance in this class by awarding you grades; in turn, you may measure your instructor’s performance by completing an instructor’s evaluation rating at the end of the course. The history of performance management is quite brief. The phrase ‘performance management’ was first coined by Beer and Ruh in 1976. Definition ● Armstrong and Baron (2004) define performance management as—’a process which contributes to the effective management of individuals and teams in order to achieve high levels of organisational performance. As such, it establishes a shared understanding about what is to be achieved and an approach to leading and developing people which will ensure that it is achieved’. ● In simple terms, performance management may be understood as the assessment of an individual’s performance in a systematic way and may be defined as ‘a structured formal interaction between a subordinate and supervisor, that usually takes the form of a periodic interview (annual or semi-annual), in which the work performance of the subordinate is examined and discussed, with a view to identifying weaknesses and strengths as well as opportunities for improvement and skills development’ ● Performance Management is an ongoing communication process, undertaken in partnership, between an employee and his or her immediate supervisor that involves establishing clear expectations and understanding about: ○ The essential job functions the employee is expected to do. ○ How the employee’s job contributes to the goals of the organisation ○ What ‘doing the job well’ means in concrete terms. ○ How employee and supervisor will work together to sustain, improve, or build on existing employee performance. Scope ● The scope of performance management is not restricted to an individual, it encompasses managing an organisation. ● Fowler (1990) in his work states that performance management is a ‘natural process of management, not a system or a technique’. ● It is about managing within the context of the business, namely, its internal and external environment ● Performance management processes are part of managing for performance, in which the whole organisation is involved. ● Here, ‘whole’ means all embracing, covering every aspect of a subject. It takes a comprehensive view of the constituents of performance, how these contribute to desired outcomes at the organisational, departments, team and individual levels, and what needs to be done to improve upon these outcomes. Process Performance management should be regarded as a flexible process, not as a ‘system’. The use of the term ‘system’ implies rigid, standardised and bureaucratic approach that is inconsistent with the concept of performance management as a flexible and evolutionary, albeit coherent, process that is applied by managers working with their teams in accordance with the circumstances in which they operate. As such, it involves managers and those whom they manage acting as partners, but within a framework that sets out how they can best work together. Performance Management Cycle Performance management can be described as a continuous self renewing cycle. The main activities are a. Role Definition ○ In this key results are as and capability requirements are discussed between employee and the manager. ○ Role definition sets out three things: ■ Purpose of the role. ■ Key results areas or principal accountabilities. ■ Key capabilities, which indicate what the role holder has to be able to do and the behaviour required for performing the role effectively. b. The Performance Agreement or the Contract ○ This defines expectations—what the individual has to achieve. An agreement usually includes: objectives and standard performance, capability profiler, performance measure and indicators, capability assessment, core values or operational requirements. c. The Personal Development Plan ○ This elucidates the actions an individual takes to develop himself during the year. d. Managing Performance throughout the Year ○ Action taken by individuals to attain the objectives as per contract and personal development plan. It involves setting directions, monitoring, measuring and taking corrective actions. e. Performance Review ○ This is a formal evaluation. Concentration should not be on what has happened but why it has happened. Tools ● Performance and Development Reviews ○ Many organisations without performance management systems operate ‘appraisals’ in which an individual’s manager regularly (usually annually) records performance, potential and development needs in a top-down process. ○ It can be argued that the perceived defects and the line manager’s disregard for the performance appraisal led to the development of more rounded concepts of performance management. ○ Nevertheless, organisations with performance management systems need to provide those involved with the opportunity to reflect on past performance as a basis for making development and improvement plans, and the performance and development review meeting provides this chance. ○ These meetings must be constructive, and various techniques can be used to conduct the sort of open, free-flowing and honest interactions needed, with the review doing most of the talking. ● Judgemental Criteria ○ Judgement about other’s work is quite complex, and can be extremely unrealistic if the judge lacks objectivity, capacity to judge the performance, sufficient time to observe, and knows in advance what he is judging. ○ It can be said that in the hands of a judicious, qualified and a well trained person such judgments can reach very close approximation of objectivity. ○ When such a judgment is obtained from a supervisor it is called supervisory judgement, when done by peers it is called peer judgment, and by self then it is referred to as self judgement. ● Methods of Employee Evaluation ○ Ranking method Ranking Method Oberg (1972) and Monga (1983) have listed some of the important ranking methods. ■ Alteration Ranking Method: ● The individual with the best performance is chosen as the ideal employee. ● Other employees are then ranked against this employee in descending order of comparative performance on a scale of best to worst performance. ● The alteration ranking method usually involves rating by more than one assessor. ● The ranks assigned by each assessor are then averaged and a relative ranking of each member in the group is determined. ● While this is a simple method, it is impractical for large groups. In addition, there may be wide variations in ability between ranks for different positions. ■ Paired Comparison ● Under this method the appraiser compares each employee with every other employee one at a time. ● The paired comparison method systematises ranking and enables better comparison among individuals to be rated. ● The evaluations received by each person in the group are counted and turned into percentage scores. The scores provide a fair idea as to how each individual in the group is judged by the assessor. ■ Person-to-person ● Rating In the person-to-person rating scales, the names of the actual individuals known to all the assessors are used as a series of standards. ● These standards may be defined as lowest, low, middle, high and highest performers. ● Individual employees in the group are then compared with the individuals used as the standards, and rated for a standard where they match the best. ○ The advantage of this rating scale is that the standards are concrete and are in terms of real individuals. ○ The disadvantage is that the standards set by different assessors may not be consistent. ■ Checklist Method ● Developed by Thurstone for measuring attitudes, in this method the assessor is furnished with a checklist of pre-scaled descriptions of behaviour, which are then used to evaluate the personnel being rated (Monga, 1983). ● The scale values of the behaviour items are unknown to the assessor, who has to check as many items as she or he believes describe the worker being assessed. ● A final rating is obtained by averaging the scale values of the items that have been marked. ■ Behaviourally Anchored Rating Scales (BARS) ● This is a relatively new technique. ● It consists of sets of behavioural statements describing good or bad performance with respect to important qualities. ● These qualities may refer to interpersonal relationships, planning and organising abilities, adaptability and reliability. These statements are developed from critical incidents collected from both the assessor and the subject. ○ Graphic Rating ■ A graphic scale ‘assesses a person on the quality of his or her work (average; above average; outstanding; or unsatisfactory)’. ■ Although graphic scales seem simplistic in construction, they have application in a wide variety of job responsibilities and are more consistent and reliable in comparison with essay appraisal. ■ The utility of this technique can be enhanced by using it in conjunction with the essay appraisal technique. ○ Forced Choice Rating Method ■ The forced-choice rating method does not involve discussion with supervisors. ■ This technique has several variations—the most common method is to force the assessor to choose the best and worst fit statements from a group of statements. ■ These statements are weighted or scored in advance to assess the employee. ■ The scores or weights assigned to individual statements are not revealed to the assessor so that she or he cannot favour any individual. ■ In this way, the assessor bias is largely eliminated and comparable standards of performance evolved for an objective. ■ However, this technique is of little value wherever performance appraisal interviews are conducted. ○ Confidential Reports ■ The Annual Confidential Reports (AcRs) are written with a view to adjudge individual performance every year in the areas of their work, conduct, character and capabilities. ■ This is the most popular method in government. ■ The system of writing confidential reports has two main objectives. ● First and foremost is to improve upon performance of the subordinates in their present job. ● The second is to assess their potentialities and to prepare them for the jobs suitable to their personality. ● The columns of ACRs are, therefore, to be filled up by the reporting, reviewing and accepting authorities in an objective and impartial manner. ○ Essay ■ The assessor writes a brief essay providing an assessment of the strengths, weaknesses and potential of the subjects. ■ In order to do so objectively, it is necessary that the assessor knows the subjects well and should have interacted with them. ■ Since the length and contents of the essays vary between assessors, essay ratings are difficult to compare. ● Learning and Development ○ Employee development is the main route followed by most organisations to improve organisational performance, which in turn requires an understanding of the processes and techniques of organisational, team and individual learning. ○ Performance reviews can be regarded as learning events, in which individuals can be encouraged to think about how and in which ways they want to develop. ○ This can lead to the drawing up of a personal development plan (PDP) setting out the actions they propose to take to develop themselves. ○ To keep development separate from performance and salary discussions, development reviews may be held at other times. ○ Increasing emphasis on talent management also means that many organisations are redefining performance management to align it to the need to identify, nurture and retain talent. ○ Development programmes are reflecting the needs for succession plans and seeking to foster leadership skills. ○ However, too much of an emphasis on talent management may be damaging to overall development needs and every effort needs to be made to ensure that development is inclusive, accessible and focused on developing organisational capability. ● Coaching ○ Coaching is an important tool in learning and development. Coaching is developing a person’s skills and knowledge so that their job performance improves, leading to the achievement of organisational objectives. ○ Coaching is increasingly recognised as a significant responsibility of line managers, and can play an important part in a personal development plan. ○ They should take place during the review meetings, but also and more importantly should be carried out throughout the year. ○ For some managers coaching comes naturally, but for many it may not and training may be needed to improve their skills. Training and Development Meaning and nature ● Training: It is a process through which an individual enhances his performance, capacity and efficiency at work. ● It is an attempt to increase a person’s current or future performance by increasing the employee’s ability to perform through improving his knowledge or skill base. ● There are three types of training and development: ○ Informal training: This refers to on the job training, it is an ongoing process. ○ Formal training: Specific training or courses that the employees are encouraged to pursue that will enhance their output. ○ Education: Specific education that trains people for specific posts in an organisational set up. Objectives 1. Bridge the gap between actual and expected performance of the employee. 2. Improve the knowledge and skills of the employee for a particular task. 3. Improve the overall performance of the individual: Bring about a change in attitude that leads to less accidents or wastage of resources. 4. Develop the employee for a position of greater authority or responsibility. 5. Orient the new employee to the organisation and his job. 6. Prepare the employee for future jobs. 7. Aid the personal development of the employee. Methods ● The method of training depends on the objective, number of people, type of training and the resources available. ● Training is mostly carried out off the job. ● However for some cases training is provided on the job. On the job ○ Job instruction training: Preparation, present, try out and follow up. ○ Job rotation ○ Coaching ○ Internship ○ Apprentice Training Off the job (Cognitive) ○ Lecture method ○ Computer training ○ Games and simulation ○ Business games ○ Role playing ○ Sensitivity training ○ Behaviour modelling ○ Vestibule training ○ Inbasket exercise ○ Case study Training and Analysis Training needs analysis is the first step in developing an employee training system. It determines the types of training that are needed in an organization. There are 3 types of Analysis that can be conducted. 1. Organizational Analysis Determines if organizational factors facilitate or inhibit training effectiveness. - Establish Goal and objectives, economic analysis, person power analysis and planning, climate and attitude surveys and resource surveys 2. Task Analysis Using job analysis methods to identify tasks performed by people in the company, conditions of performance and what tasks are to be performed and ensure employees learn to perform these identified tasks - Task inventories, interviews performance appraisals, observation and job descriptions 3. Person Analysis The process of identifying the employees who need training and determining the areas in which each individual needs to be trained - Performance appraisals, Surveys, interviews, skill and knowledge testing, critical incidents. Unit 4 The Group Group Groups can bring out the best in performance, enthusiasm, and creativity. The new workplace places great value on change and adaptation. Organisations are continually under pressure to find new ways of operation in the quest for higher productivity, total quality and service, customer satisfaction and better quality of working life. Definition ● ‘A group is a collection of individuals who have relations to one and another’ (Cartwright & Zander, 1968, p. 46). ● Bass defines a group as, ‘a collection of individuals whose existence as a collection is rewarding to the individuals, (or enables them to avoid punishment)’. ● D H Smith (1967) defines group as, ‘a largest set of two or more individuals who are jointly characterised by a network of relevant communications, a shared sense of collective identity.’ ● Kurt Lewin (1951) described the way groups and individuals act and react to changing circumstances, he named these processes ‘group dynamics’. ● Cartwright and Zander defined ‘group dynamics’ as a ‘field of inquiry dedicated to advancing knowledge about the nature of groups, the laws of their development, and their interrelations with individuals, other groups, and larger institutions’ (1968, p.7). Types ● Formal Group ○ A formal group is officially designed to serve a specific organisational purpose. An example is the work unit headed by a manager and consisting of one or more direct reports. ○ The organisation creates such a group to perform a specific task, which typically involves the use of resources to create a product, such as a report, decision, service, or commodity. ○ The head of a formal group is responsible for the group’s performance accomplishments, but all members contribute the required work. ○ Also, the head of the group plays a key linchpin role that ties it horizontally and vertically with the rest of the organisation. ○ Formal groups may be permanent or temporary. ■ Permanent work groups ● Permanent work groups, or command groups in the vertical structure, often appear on organisation charts as departments (for example, market research department), divisions (for example, consumer products division), or teams (for example, product assembly team). ● As permanent workgroups, they are each officially created to perform a specific function on an ongoing basis. ● They continue to exist until a decision is made to change or reconfigure the organisation for some reason. ■ Temporary work groups ● Temporary workgroups are task groups specifically created to solve a problem or perform a defined task. ● They often disband once the assigned purpose or task has been accomplished. ● Examples are many temporary committees and task forces that are important components of any organisation. ● Indeed, today’s organisations tend to make more use of cross functional teams or task forces for special problem solving efforts. ○ Greenbaum (1974) identified four kinds of formal networks: ■ The regulative (for example plans, regulation) ■ The innovative (for example flexibility and change) ■ The informative-instructive (for example productivity) ■ The integrative (for example maintenance of employee morale). ● Informal Group ○ Informal groups emerge without being officially designated by the organisation. ○ They form spontaneously through personal relationships or special interest, not by any specific organisational endorsement. ■ Friendship groups, for example, consist of persons with natural affinities for one another. ■ Such interest groups consist of persons who share common interests, such as an intense desire to learn about computers, non-work interests, such as community service, sports, or religion. ○ Informal groups often help people get their jobs done. ○ Through the network of interpersonal relationships, they have the potential to speed up the workflow as people assist each other in ways that formal lines of authority fail to provide. ○ They also help individuals satisfy needs that are thwarted or otherwise left unmet in the outcome of a relationship must be rewarding, and the person must derive personal and social satisfaction from the exchange. ● Virtual Group ○ Information technology is bringing a new type of group into the workplace. This is the virtual group, a group whose members convene and work together electronically via computers. Nowadays, virtual groups are increasingly becoming common in organisations. Stages of group development Tuckman (1965) developed a four stage model of group development. ● Stage 1– Forming ○ In this stage, there is high dependence on the leader for guidance and direction. ○ There is little agreement on team aims other than those received from the leader. Individual roles and responsibilities are unclear. ○ The leader must be prepared to answer lots of questions about the team’s purpose, objectives and external relationships. ○ Processes are often ignored. ● Stage 2–Stormin ○ Team members vie for position as they attempt to establish themselves in relation to other team members and the leader. ○ Leadership may receive challenges from team members. ○ Clarity of purpose increases but plenty of uncertainties persist. ○ Cliques and factions, form and there may be power struggles. ● Stage 3–Norming ○ Agreement and consensus forms largely among the team members who respond well to facilitation by leader. ○ Roles and responsibilities are clear and accepted. ○ Big decisions are made by group agreement. Smaller decisions may be delegated to individuals or small teams within the group. ○ Commitment and unity is strong. ○ The team may engage in fun and social activities. ● Stage 4–Performing ○ The team knows clearly why it is doing what it is doing. ○ The team has a shared vision and is able to stand on its own feet with no interference or participation from the leader. ○ There is focus on over-achieving goals, and the team makes most of the decisions against criteria agreed with the leader. Tuckman added a fifth stage 10 years later: ● Stage 5– Adjourning ○ Tuckman’s fifth stage, adjourning, is the break-up of the group, hopefully when the task is completed successfully, its purpose fulfilled. ○ Everyone can move on to new things, feeling good about what’s been achieved. ○ From an organisational perspective, recognition of and sensitivity to people’s vulnerabilities in Tuckman’s fifth stage is helpful, particularly if members of the group have been closely bonded and feel a sense of insecurity or threat from this change. Theories of Group Development ● Propinquity Theory ○ According to this theory, individuals affiliate with one another because of spatial or geographical nearness. In an organisation, employees working in the same office easily make a group. ● Homans Theory ○ This theory explains group formation in terms of activities, interactions and sentiments of people. Activities are assigned tasks at which people work, interactions take place when any one persons; action precedes the activity of another, and sentiments are the feelings people have towards one another. ● Balance Theory ○ Newcomb propounded this theory. He states that ‘persons are attracted towards one another on the basis of similar attitude toward common objects or goals. This common attitude can be of any type, like politics, religion, work, authority, marriage, etc. Once a relationship is formed, members strive to maintain a symmetrical balance between the common attitude and attraction. Both affiliation and interaction play a significant role in the balance theory. ● Exchange Theory ○ According to Thaibaut and Kelley, reward and cost outcomes of interaction are the basis of group formation. It is also known as the exchange theory of rewards and cost outcomes. In this, the outcome of the relationship must be rewarding, and the person must derive personal and social satisfaction from the exchange. Characteristics of groups 1. A definable membership: A collection of two or more people identifiable by name or type. 2. Group Consciousness: The members think of themselves as a group, have a collective perception of unity, a conscious identification with one another. 3. A sense of shared purpose: The members of a group have the same common task, or goals, or interests 4. Interdependence: The members are interdependent upon each other and need each other’s help. 5. Interaction 6. Ability to act in a unitary manner: The group should be able to work as a single organism. Group decision making ● The belief—characterized by juries—that two heads are better than one has long been accepted as a basic component of the U.S. legal system and those of many other countries. Today, many decisions in organizations are made by groups, teams, or committees. ● Groups versus the Individual ○ Decision-making groups may be widely used in organizations, but are group decisions preferable to those made by an individual alone? The answer depends on a number of factors. Let’s begin by looking at the strengths and weaknesses of group decision making. ● Strengths of Group Decision Making ○ Groups generate more complete information and knowledge. ○ By aggregating the resources of several individuals, groups bring more input as well as heterogeneity into the decision process. ○ They offer increased diversity of views. ○ This opens up the opportunity to consider more approaches and alternatives. ○ Finally, groups lead to increased acceptance of a solution. ○ Group members who participated in making a decision are more likely to enthusiastically support and encourage others to accept it. ● Weaknesses of Group Decision Making ○ Group decisions are time consuming because groups typically take more time to reach a solution. ○ There are conformity pressures. The desire by group members to be accepted and considered an asset to the group can squash any overt disagreement. ○ Group discussion can be dominated by one or a few members. ○ If they’re low and medium-ability members, the group’s overall effectiveness will suffer. ○ Finally, group decisions suffer from ambiguous responsibility. In an individual decision, it’s clear who is accountable for the final outcome. In a group decision, the responsibility of any single member is diluted. ● Effectiveness and Efficiency ○ Whether groups are more effective than individuals depends on how you define effectiveness. Group decisions are generally more accurate than the decisions of the average individual in a group, but less accurate than the judgements of the most accurate. ○ In terms of speed, individuals are superior. If creativity is important, groups tend to be more effective. And if effectiveness means the degree of acceptance the final solution achieves, the nod again goes to the group. ○ But we cannot consider effectiveness without also assessing efficiency. With few exceptions, group decision making consumes more work hours than an individual tackling the same problem alone. The exceptions tend to be the instances in which, to achieve comparable quantities of diverse input, the single decision maker must spend a great deal of time reviewing files and talking to other people. In deciding whether to use groups, then, managers must assess whether increases in effectiveness are more than enough to offset the reductions in efficiency. ● Summary ○ In summary, groups are an excellent vehicle for performing many steps in the decisionmaking process and offer both breadth and depth of input for information gathering. If group members have diverse backgrounds, the alternatives generated should be more extensive and the analysis more critical. When the final solution is agreed on, there are more people in a group decision to support and implement it. These pluses, however, can be more than offset by the time consumed by group decisions, the internal conflicts they create, and the pressures they generate toward conformity. In some cases, therefore, we can expect individuals to make better decisions than groups. Techniques of decision making ● Interacting Groups ○ The most common form of group decision making takes place in interacting groups. Members meet face to face and rely on both verbal and nonverbal interaction to communicate. But as our discussion of groupthink demonstrated, interacting groups often censor themselves and pressure individual members toward conformity of opinion. Brainstorming, the nominal group technique, and electronic meetings can reduce problems inherent in the traditional interacting group. ● Brainstorming ○ Brainstorming can overcome the pressures for conformity that dampen creativity 80 by encouraging any and all alternatives while withholding criticism. In a typical brainstorming session, a half-dozen to a dozen people sit around a table. The group leader states the problem in a clear manner so all participants understand. Members then freewheel as many alternatives as they can in a given length of time. To encourage members to “think the unusual,” no criticism is allowed, even of the most bizarre suggestions, and all ideas are recorded for later discussion and analysis. ○ Brainstorming may indeed generate ideas—but not in a very efficient manner. Research consistently shows individuals working alone generate more ideas than a group in a brainstorming session. One reason for this is “production blocking.” When people are generating ideas in a group, many are talking at once, which blocks the thought process and eventually impedes the sharing of ideas. The following two techniques go further than brainstorming by helping groups arrive at a preferred solution: ● Nominal Group Technique ○ The nominal group technique restricts discussion or interpersonal communication during the decision-making process, hence the term nominal. Group members are all physically present, as in a traditional committee meeting, but they operate independently. Specifically, a problem is presented and then the group takes the following steps: 1. Before any discussion takes place, each member independently writes down ideas on the problem. 2. After this silent period, each member presents one idea to the group. No discussion takes place until all ideas have been presented and recorded. 3. The group discusses the ideas for clarity and evaluates them. 4. Each group member silently and independently rank-orders the ideas. The idea with the highest aggregate ranking determines the final decision. ○ The chief advantage of the nominal group technique is that it permits a group to meet formally but does not restrict independent thinking, as does an interacting group. Research generally shows nominal groups outperform brainstorming groups. ● Electronic Meeting ○ The most recent approach to group decision making blends the nominal storming groups. assisted group, or an electronic meeting. Once the required technology is in group technique with sophisticated computer technology. It’s called a computer-assisted group, or an electronic meeting. ○ Once the required technology is in place, the concept is simple. Up to 50 people sit around a horseshoe shaped table, empty except for a series of networked laptops. Issues are presented to them, and they type their responses into their computers. ○ These individual but anonymous comments, as well as aggregate votes, are displayed on a projection screen. This technique also allows people to be brutally honest without penalty. And it’s fast because chitchat is eliminated, discussions don’t digress, and many participants can “talk” at once without stepping on one another’s toes. ○ Early evidence, however, suggests electronic meetings don’t achieve most of their proposed benefits. They actually lead to decreased group effectiveness, require more time to complete tasks, and result in reduced member satisfaction compared to face to face groups. Nevertheless, current enthusiasm for computer-mediated communications suggests this technology is here to stay and is likely to increase in popularity in the future. Each of the four group-decision techniques has its own set of strengths and weaknesses. The choice depends on what criteria you want to emphasize and the cost–benefit trade-off. An interacting group is good for achieving commitment to a solution, brainstorming develops group cohesiveness, the nominal group technique is an inexpensive means for generating a large number of ideas, and electronic meetings minimize social pressures and conflicts. Teams Definition ‘A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, set of performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.’ Types Teams can make products, provide services, negotiate deals, coordinate projects, offer advice, and make decisions.2 In this section, we describe the four most common types of teams in an organization: problem-solving teams, self-managed work teams, cross-functional teams, and virtual teams (see Exhibit 10-2). ● Problem-Solving Teams ○ In the past, teams were typically composed of 5 to 12 hourly employees from the same department who met for a few hours each week to discuss ways of improving quality, efficiency, and the work environment. ○ These problem-solving teams rarely have the authority to unilaterally implement any of their sugges-tions. ○ Merrill Lynch created a problem-solving team to figure out ways to reduce the number of days it took to open a new cash management account. ○ By suggesting cutting the number of steps from 46 to 36, the team reduced the average number of days from 15 to 8. ● Self-Managed Work Teams ○ Problem-solving teams only make recommendations. Some organizations have gone further and created teams that not only solve problems but implement solutions and take responsibility for outcomes. ○ Self-managed work teams are groups of employees (typically 10 to 15 in number) who perform highly related or interdependent jobs and take on many of the responsibilities of their former supervisors.' ■ Typically, these tasks are planning and scheduling work, assigning tasks to members, making operating decisions, taking action on problems, and working with suppliers and customers. ■ Fully self-managed work teams even select their own members and evaluate each other's performance. Supervisory positions take on decreased importance and are sometimes even eliminated. ○ But research on the effectiveness of self-managed work teams has not been uniformly positive.' ■ Self-managed teams do not typically manage conflicts well. When disputes arise, members stop cooperating and power struggles ensue, which leads to lower group performance.? ■ Moreover, although individuals on these teams report higher levels of job satisfaction than other individuals, they also sometimes have higher absenteeism and turnover rates. ■ One large-scale study of labor productivity in British establishments found that although using teams in general does improve labor productivity, no evidence supported the claim that self-managed teams performed better than traditional teams with less decision-making authority. ● Cross-Functional Teams ○ Starbucks created a team of individuals from production, global PR, global communications, and U.S. marketing to develop its Via brand of instant coffee. The team's suggestions resulted in a product that would be cost-effective to produce and distribute and that was marketed through a tightly integrated, multifaceted strategy. ■ This example illustrates the use of cross-functional teams, made up of employees from about the same hierarchical level but different work areas, who come together to accomplish a task. ○ Many organizations have used horizontal, boundary-spanning groups for decades. ■ In the 1960s, IBM created a large task force of employees from across departments to develop its highly successful System 360. ■ Today cross-functional teams are so widely used it is hard to imagine a major organizational undertaking without one. ■ All the major automobile manufacturers—Toyota, Honda, Nissan, BMW, GM, Ford, and Chrysler—currently use this form of team to coor-dinate complex projects. ■ Cisco relies on specific cross-functional teams to identify and capitalize on new trends in several areas of the software market. ● The teams are the equivalent of social-networking groups that collaborate in real time to identify new business opportunities in the field and then implement them from the bottom up. ○ Cross-functional teams are an effective means of allowing people from di-verse areas within or even between organizations to exchange information, develop new ideas, solve problems, and coordinate complex projects. ○ Of course, cross-functional teams are no picnic to manage. Their early stages of development are often long, as members learn to work with diversity and complexity. It takes time to build trust and teamwork, especially among people from different backgrounds with different experiences and perspectives. ● Virtual Teams ○ The teams described in the preceding section do their work face to face. Virtual teams use computer technology to unite physically dispersed members and achieve a common goal." ■ They collaborate online—using communication links such as wide-area networks, videoconferencing, or e-mail—whether they're a room away or continents apart. ■ Virtual teams are so pervasive, and technology has advanced so far, that it's probably a bit of a misnomer to call them "virtual." ■ Nearly all teams today do at least some of their work remotely. ○ Despite their ubiquity, virtual teams face special challenges. They may suffer because there is less social rapport and direct interaction among members. ○ Evidence from 94 studies entailing more than 5,000 groups found that virtual teams are better at sharing unique information (information held by individual members but not the entire group), but they tend to share less information overall. As a result, low levels of virtuality in teams results in higher levels of information sharing, but high levels of virtuality hinder it. ○ For virtual teams to be effective, management should ensure that: ■ (1) trust is established among members (one inflammatory remark in an email can severely undermine team trust) ■ (2) team progress is monitored closely (so the team doesn't lose sight of its goals and no team member "disappears") ■ (3) the efforts and products of the team are publicized throughout the organization (so the team does not become invisible). The difference between groups and teams Leadership Definition We will define leadership as ‘the process of directing and influencing the task related activities of group members.’ A process that shapes the goals of a group or organisation, motivates behaviour toward the achievement of those goals, and helps define group or organisational culture. It is primarily the process of influence. There are four important implications of this definition. 1. First, leadership involves other people—employees or followers. It also involves the willingness of employees/followers to accept directions from the leader. Group members help define the leader’s status and make the leadership process possible. The leadership quality of a manager would be irrelevant if there is no group of followers. 2. Second, leadership involves unequal distribution of power between leaders and the group members. Where does the power come from? There are five bases of power of managers— reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, referent power and expert power. The greater the number of these powers available to the manager, the greater is his or her potential for effective leadership. 3. Third is the ability to influence the follower’s behaviour in a number of ways. Leaders have influenced soldiers in the battlefield to make supreme sacrifice. 4. Fourth is that the leader must have values. James McGregor Burns argues that a leader who ignores the moral components of leadership may go down in history with bad reputation. Moral leadership concerns values and requires that followers be given enough knowledge of alternatives to make intelligent choices when it comes to responding to a leader’s proposal to lead. Leadership Styles ● There are two main functions of a leader, viz., task related and group maintenance. Hence, these tend to be expressed in two different styles. Managers have task orientation in that they closely supervise the employees to ensure the task is performed satisfactorily. Managers with an employee orientation put more emphasis on motivating the employee rather than controlling them. They seek friendly, trusting and respectful relationships with employees, who are often allowed to participate in decisions that affect them. ● Leadership style is the manner and approach of providing direction, implementing plans, and motivating people. Kurt Lewin (1939) led a group of researchers to identify different styles of leadership. The three major styles of leadership are (US Amy Handbook, 1973): ○ Authoritarian or autocratic ■ This style is used when leaders tell their employees what they want done and how they want it accomplished, without taking the advice of their followers ○ Participative or democratic ■ This style involves the leader and one or more employees in the decision making process (determining what to do and how to do it). ■ However, the leader maintains the final decision making authority. ○ Delegative or free reign ■ In this style, the leader allows the employees to make the decisions. ■ However, the leader is still responsible for the decisions that are made. ■ This is used when employees are able to analyse the situation and determine what needs to be done and how to do it. ● Paternalism has, at times, been equated with leadership styles. ○ Paternalism is, ‘a policy or practice of treating or governing people in a fatherly manner, especially by providing for their needs without giving them rights or responsibilities.’ ○ It is a system under which an authority undertakes to supply needs or regulate conduct of those under its control in matters affecting them as individuals, as well as in their relationships to authority and to each other. ○ In today’s climate, where participation and involvement in the workplace are much more popular than before, this approach is not very popular. Although prevalent, it is more authoritarian. Approaches to Leadership The subject of leadership is so vast and perceived to be so critical, it has generated a huge body of literature. Each researcher working in the field has tried to explain leadership from a different perspective. Broadly, there are four distinct approaches to leadership, viz., Traits Theory, Behaviouristic Theory, Contingency Theory and Charismatic Theories of leadership. Traits Theory ● The first systematic study of leadership began in the 1930s with the development of trait theories, which focus on identifying the individual characteristics that make people good leaders. ● The search for personality, social, physical, or intellectual attributes that differentiate leaders from non-leaders goes back to the earliest stages of leadership research. ● However, the early attempts to identify the distinctive traits of leaders did not result in much success. ● A breakthrough came when researchers began organizing the traits around the big five personality traits. ● Accordingly, they found extraversion to be the most important trait of effective leaders, but it is more strongly related to the way leaders emerge than to their effectiveness. ● Unlike agreeableness and emotional stability, conscientiousness and openness to experience also showed strong relationships to leadership, though not quite as strong as extraversion. ● Another trait that may indicate effective leadership is emotional intelligence with empathy as one of its core components. ● Ask people what good leadership is, and it is quite likely you will get a response that suggests good leadership can somehow be defined in terms of traits or characteristics. ● Personal characteristics of a leader are emphasized. The implicit idea is that a leader is born not made. ● All leaders are supposed to have certain stable characteristics that make them leaders. ● The focus is on identifying and measuring traits that distinguish leaders from non-leaders, or effective from ineffective leaders. Three main categories of personal characteristics have been included in the search of the ‘great man.’ ○ (a) Physical features, such as height, physique, appearance, and age; ○ (b) Ability characteristics, such as intelligence, knowledge, and fluency of speech; ○ (c) Personality traits, such as dominance, emotional control and expressiveness, introversion and extraversion. RM Stogdill (1948) concluded that a ‘person does not become leader by virtue of the possession of some combination of traits.’ No traits are universal. Action has to be taken with traits. However, traits do matter and studies have revealed that there are some common traits which differentiate leaders from followers. Behaviouristic Theory ● After the problems with the trait approach became evident, researchers turned to an examination of the leader’s behaviour. In this approach, effectiveness of a leader is dependent on the exerted leadership style. ● The approach implied that leadership is a behavioural pattern, which can be learned. Thus, according to this approach, once one was able to discover the ‘right’ style, people could be trained to exhibit that behaviour and become better leaders (Bass, 1990). ● The most prominent studies were those undertaken by the University of Michigan and by the Ohio State University. Interestingly, both studies arrived at similar conclusions. ● The Ohio State researcher concluded that leadership style could best be described as varying along two dimensions, i.e.,‘consideration’ and ‘initiating structure.’ ● The second study was carried out at the University of Michigan. The results of these studies were summarised by Likert (1961, 1967). They show that three types of leader behaviour help in differentiating between an effective and an ineffective leader: ○ Production centered behaviour: When a leader pays close attention to the work of subordinates, explains work procedures, and is keenly interested in their performance. ○ Employee centered behaviour: When the leader is interested in developing a cohesive work group, and in ensuring employees are satisfied with their jobs. ○ Participative leadership: When the leader is interested in taking the employees along with him for accomplishment of the task. ● Rather than concentrating on what leaders are, as the trait approach did, the behavioural approach forced researchers look to at what leaders do. ● The main shortcomings of the behavioural approach were its focus on finding a dependable prescription for effective leadership. More info on behaviour theory ● The failures of early trait studies led researchers in the late 1940s through the 1960s to wonder whether there was something unique in the way effective leaders behave. ● Behaviour leadership theories focus on identifying what leaders actually do, in the hope that this approach will provide a better understanding of leadership processes. ● The most comprehensive concepts resulted from the Ohio State Studies in the late 1940s. ● The studies narrowed the list to two that substantially accounted for most of the leadership behavior described by employees: initiating structure and consideration. ● Initiating structure is the extent to which a leader is likely to define and structure his or her role and those of employees in the search for goal attainment. It includes behavior that attempts to organize work, work relationships, and goals. A leader high in initiating structure is someone who “assigns group members to particular tasks,” “expects workers to maintain definite standards of performance,” and “emphasizes the meeting of deadlines.” ● Consideration is the extent to which a person’s job relationships are characterized by mutual trust, respect for employees’ ideas, and regard for their feelings. A leader high in consideration helps employees with personal problems, is friendly and approachable, treats all employees as equals, and expresses appreciation and support. In a recent survey, when asked to indicate what most motivated them at work, 66 percent of employees mentioned appreciation ● Another set of studies at the University of Michigan Research Centre proposed two behavioral dimensions; employee-oriented leader and production oriented leaders. ● Employee-oriented leaders emphasized on interpersonal relations, takes a personal interest in the needs of employees, and accepts individual differences among members. ● Production-oriented leader emphasized the technical or task aspects of the job, focusing on accomplishing the group’s tasks. ● These dimensions are closely related to the Ohio State dimensions. Employee-oriented leadership is similar to consideration, and production-oriented leadership is similar to initiating structure. ● Studies found the followers of leaders high in consideration were more satisfied with their jobs, were more motivated, and had more respect for their leader. ● Initiating structure was more strongly related to higher levels of group and organization productivity and more positive performance evaluations. ● Some researchers also suggest that there are differences in international preferences for initiating structure and consideration based on the cultures and values of the society. Considerate leaders are more likely to be successful in cultures such as Brazil where leaders are expected to work with the group. Leaders high in initiating structure may be successful in cultures like France where they have a more bureaucratic (administrative) view of leaders. The Managerial Grid ● Some researchers proposed ‘universal’ theories of effective leader’s behaviour, stating that; for instance, effective leaders are both people-task oriented, so called ‘High-high’ leaders. ● Blake and Mouton (1985) tried to show an individual’s style of leadership on a 9x9 grid consisting of two separate dimensions, viz., concern for production and concern for people, which are similar to the concept of employee centered and production-centered styles of leadership mentioned earlier. ● The grid has nine possible positions along each axis, creating a total of eighty one possible styles of leader behaviour. The managerial grid thus identifies the propensity of a leader to act in a particular way. The (9,1) style is known as task management which focuses wholly on production. ● Managers with this style are exceptionally competent with the technicalities of a particular job but are miserable failures in dealing with people. The (1,9) style, in contrast emphasises people to the exclusion of task performance and is known as country club style of management. Contingency Theories ● The main proposition in contingency approaches is ‘that the effectiveness of a given leadership style is contingent on the situation’, implying that certain leader behaviours would be effective in some situations but not in others. ● Contingency theories differ from both trait and behavioral theories by formally taking into account situational or contextual variables. ● Fiedler’s Model ○ The first and perhaps the most popular situational theory to be advanced was the ‘Contingency Theory of Leadership Effectiveness’ developed by Fred E. Fiedler. This theory explains that group performance is a result of interaction of two factors. These factors are known as leadership style and situational favorableness. In Fiedler’s model, leadership effectiveness is the result of interaction between the style of the leader and the characteristics of the environment in which the leader works. According to Fiedler, ‘an individual’s leadership style depends upon his or her personality and is, thus, fixed’. In order to classify leadership styles, Fiedler has developed an index called the Least Preferred coworker (LPC) scale. ○ The LPC scale asks a leader to think of all the persons with whom he or she has ever worked, and then to describe the one person with whom he or she worked least well. This person can be from the past, or someone he or she is currently working with. From a scale of 1 through 8, the leaders are asked to describe this person on a series of bipolar scales, such as the ones shown below: Unfriendly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Friendly Uncooperative 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cooperative Hostile 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Supportive Guarded 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Open ● The responses to these scales (usually sixteen in total) are summed and averaged: ○ (a) High LPC score suggests that the leader has a human relations orientation. ○ (b) Low LPC score indicates task orientation According to Fiedler, ‘a task orientated style of leadership is more effective than a considerate (relationship orientated) style under extreme situations, that is, when the situation, is either very favourable (certain) or very unfavourable (uncertain)’. The task orientated leader, who gets things accomplished, proves to be the most successful. If the leader is considerate (relationship orientated), he or she may waste so much time during disaster, that things may get out of control and lives might be lost. Fiedler’s theory has some very interesting implications for the management of leaders in organisations: 1. The favourableness of leadership situations should be assessed using the instruments developed by Fiedler (or, at the very least, by a subjective evaluation). 2. Candidates for leadership positions should be evaluated using the LPC scale. 3. If a leader is being sought for a particular leadership position,a leader with the appropriate LPC profile should be chosen (task orientated for very favourable or very unfavourable situations and relationship orientated for intermediate favourableness). 4. If a leadership situation is being chosen for a particular candidate, a situation(workteam,department, et cetera.) should be chosen which matches his/her LPC profile (very favourable or unfavourable for task orientated leaders and intermediate favourableness for relationship orientated leader). Heresy and Blanchard’s Situational Model ○ The situational leadership model, developed by Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard, suggests that the leader’s behaviour should be adjusted according to the maturity level of the followers. The level of maturity, or the readiness of the followers, was assessed to the extent that the followers had the ability and willingness to accomplish a specific task. ○ The leader behaviour was determined by the same dimensions as used in the Ohio Studies, viz., production orientation and people orientation. According to the situational mode, a leader should use a telling style (high concern for task and low concern for people) with the least matured group of followers who are neither able nor willing to perform. A selling style of leadership (high concern for both task and relationship) is required for dealing with the followers with the next higher level of maturity, that is, those who are willing but unable to perform the task at the required level. The able but unwilling followers are the next matured group and require a participating style from the leader, characterised by high concern for consideration and low emphasis on task orientation. Finally, the most matured followers, who are both able and willing, require a delegating style of leadership. The leader working with this kind of followers must learn to restrain himself from showing too much concern for either task or relationship as followers themselves accept the responsibility for their performance. Though this theory is difficult test empirically, it has its intuitive appeal and is widely used for training and development in organisations. In addition, the theory focuses attention on followers as a significant determinant of any leadership process. The Path Goal Theory ○ In recent times, one of the most appreciated theories of leadership is the Path Goal Theory as offered by Robert House, which is based on the Expectancy Theory of Motivation. According to this theory, the effectiveness of a leader depends on the following propositions: ■ Leader behaviour is acceptable and satisfying to followers to the extent that they see it as an immediate source of satisfaction, or as instrumental to future satisfaction ■ Leader behaviour is motivational to the extent that ● It makes the followers’ needs satisfaction contingent or dependent on effective performance, and ● It complements the followers’ environment by providing the coaching, guidance, support, and rewards necessary for realising the linkage between the level of their performance and the attainment of the rewards available. ○ The leader selects from any of the four styles of behaviour which is most suitable for the followers at a given point of time. These are directive, supportive, participative, and achievement oriented according to the needs and expectations of the followers. In other words, the path goal theory assumes that leaders adapt their behaviour and style to fit the characteristics of the followers and the environment in which they work. Transformational Leadership ● James MacGregor Burns (1978) conceptualised leadership as either transactional or transformational. Transactional leaders are those who lead through social change. As Burns (1978) notes, politicians, for example, lead by ‘exchanging one thing for another: jobs for votes, or subsidies for campaign contributions.’ Transformational leaders, on the other hand, are those who stimulate and inspire followers to both achieve extraordinary outcomes and, in the process, develop their own leadership capacity. Transformational leaders help followers grow and develop into leaders by responding to individual followers’ needs by empowering them and by aligning the objectives and goals of their individual followers, the leader, the group, and the larger organisation. It has been observed that transformational leadership can move followers to exceed expected performance, as well as reach high levels in work to the follower’s satisfaction and as per the follower’s commitment to the group and organisation (Bass, 1985). ● Bass (1985) extended charismatic leadership to the theory of transformational leadership where the leader is able to inspire and activate subordinates to ‘perform beyond expectations’ and to achieve goals beyond those normally set. Bass’ theory posits that the transformational leader achieves greater than expected performance through any one of three interrelated ways: (a) an increased level of awareness by subordinates about the importance of designated outcomes, (b) by getting individuals to transcend their own selfinterest for the sake of the team, and (c) by altering the subordinates’ need levels on Maslow’s hierarchy or expanding the set of needs. ● The transformational leader gains a greater commitment from subordinates and induces them to transcend personal self-interest for the betterment of the group or organisation not only with charisma but also by serving as a coach, teacher, or mentor (Bass, 1985). Thus, the transformational leader is able to activate higher order needs of esteem and self actualisation among subordinates. House’s Theory of Charismatic Leadership ● House (1977) defines charismatic leadership as referring to a leader who has charismatic effects on followers to an unusually high degree. These effects include devotion, trust, unquestioned obedience, loyalty commitment, identification, confidence in ability to achieve goals and radical changes in beliefs and values. ● Charismatic leadership is stated to have three core components, i.e., envisioning, empathy, and empowerment. A charismatic leader’s envisioning behaviour influences followers’ need for achievement, and the leader’s empathic behaviour stimulates followers’ need for affiliation. ● Charismatic leadership theory asserts that exceptional leaders create a connection with followers, attend to their individual needs, and inspire followers to achieve beyond personal limits. By appealing to higher order individual values and magnanimous ideals, charismatic leaders enhance the commitment of followers to an eloquent vision and arouse followers to develop new ways of thinking about problems. Unit 5 Communication and Organizational culture Communication Definition Functions ● Communication serves four major functions within a group or organization: ○ Control ■ Communication acts to control member behavior in several ways. ■ Organizations have authority hierarchies and formal guidelines employees are required to follow. ■ When employees must communicate any job-related grievance to their immediate boss, follow their job description, or comply with company policies, communication is performing a control function. ■ Informal communication controls behavior too. ● When work groups tease or harass a member who produces too much (and makes the rest of the group look bad), they are informally communicating, and controlling, the member’s behavior. ○ Motivation ■ Communication fosters motivation by clarifying to employees what they must do, how well they are doing it, and how they can improve if performance is subpar. ■ The formation of specific goals, feedback on progress toward the goals, and reward for desired behavior all stimulate motivation and require communication. ○ Emotional expression ■ Their work group is a primary source of social interaction for many employees. ■ Communication within the group is a fundamental mechanism by which members show their satisfaction and frustrations. ■ Communication, therefore, provides for the emotional expression of feelings and fulfillment of social needs ○ Information ■ The final function of communication is to facilitate decision making. Communication provides the information individuals and groups need to make decisions by transmitting the data needed to identify and evaluate choices. ■ Almost every communication interaction that takes place in a group or organization performs one or more of these functions, and none of the four is more important than the others. ■ To perform effectively, groups need to maintain some form of control over members, stimulate members to perform, allow emotional expression, and make decision choices. Process ● Before communication can take place it needs a purpose, a message to be conveyed between a sender and a receiver. The sender encodes the message (converts it to a symbolic form) and passes it through a medium (channel) to the receiver, who decodes it. The result is transfer of meaning from one person to another. Exhibit 11-1 depicts this communication process. The key parts of this model are (1) the sender, (2) encoding, (3) the message, (4) the channel, (5) decoding, (6) the receiver, (7) noise, and (8) feedback. ● The sender initiates a message by encoding a thought. The message is the actual physical product of the sender’s encoding. When we speak, the speech is the message. When we write, the writing is the message. When we gesture, the movements of our arms and the expressions on our faces are the message. The channel is the medium through which the message travels. The sender selects it, determining whether to use a formal or informal channel. Formal channels are established by the organization and transmit messages related to the professional activities of members. They traditionally follow the authority chain within the organization. ● Other forms of messages, such as personal or social, follow informal channels, which are spontaneous and emerge as a response to individual choices. The receiver is the person(s) to whom the message is directed, who must first translate the symbols into understandable form. This step is the decoding of the message. Noise represents communication barriers that distort the clarity of the message, such as perceptual problems, information overload, semantic difficulties, or cultural differences. The final link in the communication process is a feedback loop. Feedback is the check on how successful we have been in transferring our messages as originally intended. It determines whether understanding has been achieved. Direction of communication Communication can flow vertically or laterally. We further subdivide the vertical dimension into downward and upward directions. Downward Communication ● Communication that flows from one level of a group or organization to a lower level is downward communication. ● Group leaders and managers use it to assign goals, provide job instructions, explain policies and procedures, point out problems that need attention, and offer feedback about performance. ● When engaging in downward communication, managers must explain the reasons why a decision was made. Although managers might think that sending a message one time is enough to get through to lower-level em-ployees, most research suggests managerial communications must be repeated several times and through a variety of different media to be truly effective!' ● Another problem in downward communication is its one-way nature; gener-ally, managers inform employees but rarely solicit their advice or opinions. Companies like cell phone maker Nokia actively listen to employee's suggestions, a practice the company thinks is especially important to innovation. ● The best communicators explain the reasons behind their downward com-munications but also solicit communication from the employees they supervise. That leads us to the next direction: upward communication. Upward Communication ● Upward communication flows to a higher level in the group or organization. It's used to provide feedback to higher-ups, inform them of progress toward goals, and relay current problems. Upward communication keeps managers aware of how employees feel about their jobs, co-workers, and the organization in gen-eral. ● Managers also rely on upward communication for ideas on how conditions can be improved. Given that most managers' job responsibilities have expanded, upward communication is increasingly difficult because managers are overwhelmed and easily distracted. ● To engage in effective upward communication, try to reduce distractions, communicate in headlines not paragraphs, support your headlines with actionable items , and prepare an agenda to make sure you use your boss's attention well. Lateral Communication ● When communication takes place among members of the same work group, members of work groups at the same level, managers at the same level, or any other horizontally equivalent workers, we describe it as lateral communication. ● Lateral communication is needed even if a group or an organization's vertical communications are effective? Because it saves time and facilitates coordination. ● Some lateral relationships are formally sanctioned. More often, they are informally created to short-circuit the vertical hierarchy and expedite action. ○ So from management's viewpoint, lateral communications can be good or bad. ○ Because strictly adhering to the formal vertical structure for all communications can be inefficient, lateral communication occurring with management's knowledge and support can be beneficial. ○ But it can create dysfunctional conflicts when the formal vertical channels are breached, when members go above or around their superiors to get things done, or when bosses find actions have been taken or decisions made without their knowledge. Types of Communication Interpersonal Communication ● Oral Communication ● Written Communication ● Nonverbal Communication Organisational Communication ● Formal Small-Group Networks ○ Formal organizational networks can be very complicated, including hundreds of people and a half-dozen or more hierarchical levels. To simplify our discus-sion, we've condensed these networks into three common small groups of five people each (see Exhibit 11-3): ■ Chain ● The chain rigidly follows the formal chain of command; this network approximates the communication channels you might find in a rigid three-level organization. ■ Wheel ● The wheel relies on a central figure to act as the conduit for all the group's communication; it simulates the communication network you would find on a team with a strong leader. ■ All channels. ● The all-channel network permits all group members to actively communicate with each other; it's most often characterized in practice by self-managed teams, in which all group members are free to con-tribute and no one person takes on a leadership role. ■ The effectiveness of each network depends on the dependent variable that concerns you. The structure of the wheel facilitates the emergence of a leader, the all-channel network is best if you desire high mem-ber satisfaction, and the chain is best if accuracy is most important. Exhibit 114 leads us to the conclusion that no single network will be best for all occasions. ● The Grapevine ○ The informal communication network in a group or organization is called the grapevine.' Although the rumors and gossip transmitted through the grapevine may be informal, it's still an important source of information. ○ A recent report shows that grapevine or word-of-mouth information from peers about a company has important effects on whether job applicants join an organization. ○ Rumors emerge as a response to situations that are impor-tant to us, when there is ambiguity, and under conditions that arouse anxiety. The fact that work situations frequently contain these three elements explains why rumors flourish in organizations. ○ The secrecy and competition that typi-cally prevail in large organizations—around the appointment of new bosses, the relocation of offices, downsizing decisions, or the realignment of work assignments—encourage and sustain rumors on the grapevine. ○ A rumor will persist until either the wants and expectations creating the uncertainty are fulfilled or the anxiety has been reduced. What can we conclude about the grapevine? ○ Certainly it's an important part of any group or organization communication network and is well worth understanding. It gives managers a feel for the morale of their organization, identifies issues employees consider important, and helps tap into employee anxieties. ○ The grapevine also serves employees' needs: small talk creates a sense of closeness and friendship among those who share information, although research suggests it often does so at the expense of those in the "out" group. ○ There is also evidence that gossip is driven largely by employee social networks that managers can study to learn more about how positive and negative information is flowing through their organization. ○ Thus, while the grapevine may not be sanctioned or controlled by the organization, it can be understood. ○ Can managers entirely eliminate rumors? no. What they should do, however, is minimize the negative consequences of rumors by limiting their range and impact. ● Electronic Communications ○ Email ■ Drawbacks: ● Risk of misinterpreting the message ● Difficult to communicate negative messages ● Time consuming due to amount of emails ● Limited expression of emotions ● Privacy concerns ○ Instant Messaging ○ Social Networking ○ Blogs ○ Video conferencing Barriers to effective communication ● Filtering: Manipulating information so that the receiver will see it more favourably. ● Selective Perception: The perceiver’s bias that can play a role. ● Information overload: Tendency to ignore, pass over, or forget when there is too much information. ● Emotions: Messages will be interpreted differently based on the perceiver’s emotions. ● Language: Jargon and context can take certain people out of the conversation. ● Silence: Any party withholding information or hesitating to speak. ● Communication Apprehension: Social anxiety. ● Lying Organizational Culture Definition ● Organizational Culture is a common perception held by the organization’s members; a system of shared meaning. ● O’Reilly and Chatman (1996, p.160) define organisational culture as, ‘A system of shared Culture. values (that define what is important) and norms that define appropriate attitudes and behaviours for organisational members (how to feel and behave).’ ● Becker and Geer (1960) define organisational culture as, ‘A set of common understandings around which action is organised, . . . finding expression in language whose nuances are peculiar to the group.’ ● Louis (1980) defines it as, ‘A set of understandings or meanings shared by a group of people that are largely tacit among members, and are clearly relevant and distinctive to the particular group, which are also passed on to new members.’ ● Allaire and Firsirotu (1984) defined organisational culture as, ‘A system of knowledge, of standards for perceiving, believing, evaluating and acting . . . that serve to relate human communities to their environmental settings.’ ● Schein (373-374) defined culture of a group as, ‘A pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.’ Characteristics Which values characterise an organization’s culture? Even though culture may not be immediately observable, identifying a set of values that might be used to describe an organisation’s culture helps us identify, measure, and manage culture more effectively. The character of culture provides the direction of the cultural impact. Robbins (1993) has listed ten characteristics of culture: ● Member identity ● Group emphasis ● People focus ● Unit integration ● Control ● Risk tolerance ● Reward criteria ● Conflict tolerance ● Means-end orientation ● Open system focus Types The four types are 1. Consensual: The collaborative and cohesive clan. 2. Entrepreneurial: The innovative and adaptable adhocracy. 3. Bureaucratic: The controlled and consistent hierarchy. 4. Competitive: The competitive and customer focused market. A review of 94 studies found that: ● Job attitudes were especially positive in clan-based cultures. ● Innovation was especially strong in market cultures. ● Financial performance was especially good in market cultures. Characteristics of Organisational Culture Profile Organisational Culture Profile was developed to examine the congruence between individual and organisational values. In organisational culture profile, culture is represented by seven distinct values. The organisational culture profile has been identified as a measure of culture and values as one facet of culture at the organisational level. Ashkansay, Broadfoot and Falkus (2000) reported that organisational culture profile was one of the only few instruments to provide details concerning reliability and validity. The Seven Distinct Values of Organisational Culture Profile: 1. Innovative Culture a. According to the organisational culture profile framework, companies that have innovative culture are flexible, adaptable, and experiment with new ideas. b. These companies are characterised by a flat hierarchy in which titles and other status distinctions tend to be downplayed. 2. Aggressive Culture a. Companies with aggressive culture value competitiveness and outperforming competitors. b. For example, Microsoft Corporation is often identified as a company with an aggressive culture. i. The company has faced a number of antitrust lawsuits and disputes with competitors over the years. ii. In aggressive companies, people may use language such as, ‘We will kill our competition.’ iii. In the past, Microsoft executives often made statements such as, ‘We are going to cut off Netscape’s air supply. iv. Everything they are selling we are going to give away.’ Its aggressive culture is cited as a reason for getting into new legal troubles before old ones are resolved 3. Outcome Oriented Culture a. The organisational culture profile framework describes outcome-oriented cultures as those that emphasise achievement, results, and action as important values. 4. Stable Culture a. Stable cultures are predictable, rule oriented, and bureaucratic. b. These organisations aim to coordinate and align individual effort for greatest levels of efficiency. c. When the environment is stable and certain, these cultures may help the organisation be effective by providing stable and constant levels of output. d. These cultures prevent quick action, and, as a result, may be a misfit to a changing and dynamic environment. e. Public sector institutions may be viewed as stable cultures. Its bureaucratic culture is blamed for killing good ideas in early stages and preventing the company from innovating. 5. People Oriented Culture a. People-oriented cultures value fairness, supportiveness, and respect individual rights. b. These organisations truly live the mantra that ‘people are their greatest asset.’ c. In addition to having fair procedures and management styles, these companies create an atmosphere where work is fun and employees do not feel that they are required to choose between work and other aspects of their lives. d. In these organisations, there is a greater emphasis on and expectation of treating people with respect and dignity. e. One study of new employees in accounting companies found that employees, on an average, stayed fourteen months longer in companies with people-oriented cultures. 6. Team Oriented Culture a. Companies with team-oriented cultures are collaborative and emphasise cooperation among employees. b. For example, Kingfisher Airlines Company facilitates a team-oriented culture by crosstraining its employees so that they are capable of helping each other when needed. i. The company also places emphasis on training intact work teams. ii. Employees participate in twice daily meetings, named morning overview meetings, and daily afternoon discussions where they collaborate to understand sources of problems and determine future courses of action. iii. In Kingfisher’s selection system, applicants who are not viewed as team players are not hired as employees. iv. In team-oriented organisations, members tend to have more positive relationships with their co-workers, and particularly with their managers. 7. Detail Oriented Culture a. Organisations with detail-oriented cultures emphasise precision and paying attention to details. b. Such a culture gives a competitive advantage to companies in the hospitality industry by helping them differentiate themselves from others. c. For example, Taj Group of Hotels and the Oberoi Group of Hotels are among hotels who keep records of all customer requests, such as which newspaper the guest prefers, or what type of pillow the customer uses. i. This information is put into a computer system and is used to provide better service to returning customers. ii. Any requests hotel employees receive, as well as overhear, might be entered into the database to serve customers better. iii. Recent guests to Four Seasons Paris, who were celebrating their 21st anniversary, were greeted with a bouquet of twenty one roses on their bed. Such clear attention to detail is an effective way of impressing customers and ensuring repeat visits. iv. McDonald’s Corporation is another company that specifies in detail how employees should perform their jobs by including photos of exactly how french fries and hamburgers should look when prepared properly. In addition to the seven cultures, there are two dimensions not included in OCP list but have assumed importance lately. 8. Service Culture a. Service culture emphasises upon high quality service. b. It is not one of the dimensions of OCP, but given the importance of retail industry in the overall economy, having a service culture can make or break an organisation. c. Some organisations famous for their service culture include Maruti Suzuki, Taj Group of Hotels and Kingfisher Airlines. i. In these organisations, employees are trained to serve the customer well, and cross-training is the norm. Employees are empowered to resolve customer problems in ways they see fit. ii. Because employees with direct customer contact are in the best position to resolve any issues, employee empowerment is truly valued in these companies. iii. For example, HDFC Bank Ltd is known for its service culture. 1. All employees are trained in all tasks to enable any employee to help customers when needed. 2. Branch employees may come up with unique ways in which they serve customers better, such as opening their lobby for community events. 3. They also reward employee service performance through bonuses and incentives. 9. Safety Culture a. Some jobs are safety sensitive. For example, defence forces, loggers, aircraft pilots, fishing workers, steel workers, and roofers are among the top ten most dangerous jobs in the India (Christie, 2005). b. In organisations where safety sensitive jobs are performed, creating and maintaining a safety culture is important. c. A culture that emphasises safety as a strong workplace norm provides a competitive advantage, because the organisation can reduce accidents, maintain high levels of morale and employee retention, and increase profitability by cutting workers’ compensation insurance costs. d. Some companies suffer severe consequences when they are unable to develop such a culture. e. In companies that have a safety culture, there is strong commitment to safety starting at management level and trickling down to lower levels. Uniformity of Cultures ● Most large organizations have a dominant culture and numerous subcultures. ● A dominant culture expresses the core values a majority of members share and that give the organization its distinct personality. ● Core values are the primary or dominant values that are accepted throughout the organization. ● Subcultures are minicultures within an organization, typically defined by department designations and geographical separation. oiuStrong v/s weak culture ● All organisations have cultures; some appear to have stronger, more deeply rooted cultures than others. ○ Organisational cultures differ in their strength. ○ Strength of a culture refers to the amount of overlapping support and locations providing repetition of dominant cultural elements as well as the intensity of member identification with the culture. ○ The character of the culture provides the direction of cultural impact and its strength provides its force. ○ The stronger the culture, the more impact it can have on employee commitment, performance and on corporate decisions. ● A strong culture is shared by organisational members. ○ In other words, if most employees in the organisation show consensus regarding the values of the company, it is possible to talk about the existence of a strong culture. ○ A culture’s content is more likely to affect the way employees think and behave when the culture in question is strong. ● There are three interrelated explanations for the performance benefits of strong cultures. ○ First, widespread consensus and endorsement of organisational values and norms facilitates social control within the firm. ■ When there is broad agreement that certain behaviours are more appropriate than others, violations of behavioural norms may be detected and corrected faster. ■ Corrective actions are more likely to come from other employees, regardless of their place in the formal hierarchy. ■ Informal social control is therefore likely to be more effective and cost less than formal control structures (O’Reilly and Chatman, 1996). ○ Second, strong corporate cultures enhance goal alignment. ■ With clarity about corporate goals and practices, employees face less uncertainty about the proper course of action when faced with unexpected situations and can react appropriately. ■ Goal alignment also facilitates coordination, as there is less room for debate between different parties about the firm’s best interests (Kreps, 1990; Cremer, 1993; Hermalin, 2001). ○ Finally, strong cultures can enhance employees’ motivation and performance because they perceive that their actions are freely chosen (O’Reilly, 1989; O’Reilly and Chatman, 1996). ● A strong culture may sometimes outperform a weak culture because of the consistency of expectations. ○ In a strong culture, members know what is expected of them, and the culture serves as an effective control mechanism on member behaviours. ○ Research shows that strong cultures lead to more stable corporate performance in stable environments. ○ However, in volatile environments, the advantages of culture strength disappear (Sorensen, 2002). ● Pointers Strong cultures lead to: ○ Organization’s core values being both intensely held and widely shared and consistent. ○ Greater influence on employees behaviour. ○ High degree of sharedness and intensity increase an internal climate of high behavioral control. ○ Strong culture – lower employee turnover – higher agreement among members about what the organization stands for. ○ Uniformity, cohesiveness, loyalty and commitment Culture and Formalisation ● A strong organisational culture increases behavioural consistency. In this sense, it should be recognised that strong cultures act as a substitute for formalisation. ● Formalisation is done in an organisation by laying down rules and regulations to regulate the behaviour of an employee. ● High formalisation in an organisation creates predictability, orderliness and consistency. ● Strong culture achieves the same without need for written documentation. ● Therefore, we should view formalisation and culture as two different modes for achieving the same end. ● Stronger the organisational culture less is the need for developing formal rules and regulations to guide employee behaviour. Functions Organisational culture has four functions: 1. Organisational identity: Organisational culture creates distinction between two organisations. It also conveys sense of identity for organisation members. 2. Collective commitment: Culture facilitates the generation of commitment to something larger that one’s individual self interest. Culture is a social glue that helps hold the organisation together by providing appropriate standards for what employees should say and do. 3. Sense making device: Culture serves as a sense making and control mechanism that guides and shapes the attitudes and behaviour of employees. 4. Social system stability: The role of culture is influencing employees’ behaviour. It has wide span of control, and limits independent functioning of a member detrimental to it. The shared meaning provided by culture ensures that everyone is pointed in the same direction. Limitations Commented [2]: Formalization is the extent to which an organization's policies, procedures, job descriptions, and rules are written and explicitly articulated. Formalized structures are those in which there are many written rules and regulations. 1. Barrier to change: When the cultural values are not aligned with those that will increase the organisation's effectiveness in dynamic environments, they can create a barrier to implementing the necessary changes. 2. Barrier to diversity: There is a managerial conflict that exist because of culture. Organisations seek to hire people of diverse backgrounds in order to increase the quality of decision making and creativity. But strong cultures, by their very nature, often seek to minimise diversity. Balancing the need for diversity with the need for strong culture is an ongoing managerial challenge. 3. Barrier to acquisitions and mergers: One of the primary concerns in mergers and acquisitions in recent years has been the cultural compatibility between the two firms, as the main cause for the failure of these combinations has been cultural conflict. Positive organizational culture ● A positive organizational culture emphasizes building on employee strengths, rewards more than it punishes, and emphasizes individual vitality and growth. ● Building on Employee Strengths ○ Although a positive organizational culture does not ignore problems, it does emphasize showing workers how they can capitalize on their strengths ○ Example: Larry Hammond ■ Hammond is CEO of Auglaize Provico, an agribusiness company based in Ohio. ■ In the midst of the firm’s worst financial struggles, when it had to lay off onequarter of its workforce, with the help of Gallup consultant Barry Conchie, Hammond focused on discovering and using employee strengths and helped the company turn itself around. ● Rewarding More Than Punishing ○ Although most organizations are sufficiently focused on extrinsic rewards such as pay and promotions, they often forget about the power of smaller (and cheaper) rewards such as praise. ○ Many managers withhold praise because they’re afraid employees will coast or because they think praise is not valued. ○ Example: El´zbieta Górska-Kolodziejczyk, ■ He is a plant manager for International Paper’s facility in Kwidzyn Poland. ■ Employees work in a bleak windowless basement and staffing is roughly one-third its prior level, while production has tripled. ■ These challenges had done in the previous three managers. So when GórskaKolodziejczyk took over, although she had many ideas about transforming the organization, at the top were recognition and praise. ■ She initially found it difficult to give praise to those who weren’t used to it, especially men. ■ Over time, however, she found they valued and even reciprocated praise. ● Emphasizing Vitality and Growth ○ A positive culture recognizes the difference between a job and a career. ○ It supports not only what the employee contributes to organizational effectiveness but also how the organization can make the employee more effective—personally and professionally. ○ Example: Philippe Lescornez ■ At Masterfoods in Belgium, Philippe Lescornez leads a team of employees including Didier Brynaert, who works in Luxembourg, nearly 150 miles away. ■ Brynaert was considered a good sales promoter who was meeting expectations when Lescornez decided Brynaert’s job could be made more important if he were seen less as just another sales promoter and more as an expert on the unique features of the Luxembourg market. ■ So Lescornez asked Brynaert for information he could share with the home office. He hoped that by raising Brynaert’s profile in Brussels, he could create in him a greater sense of ownership for his remote sales territory. Categories ● Observed behavioural regularities when people interact ○ The language they use, the customs, traditions that evolve, and the rituals they employ in a wide variety of situations ● Group Norms ○ The implicit standards and values that evolve in working groups ● Espoused Values ○ The articulated, publicly announced principles and values that group claims to be trying to achieve, such as ‘product quality’ or ‘price leadership’ ● Rules of the Game ○ The implicit unwritten rules for getting along in the organisation; ‘the ropes’ that a newcomer must learn in order to become an accepted member ● Climate ○ The feeling that is conveyed in a group by the physical layout and the way in which members of the organisation interact with each other, with customers, or other outsiders ● Habits of thinking, mental models, and linguistic paradigms ○ The shared cognitive frames that guide the perceptions, thought, and language used by the members of a group and taught to new members in the early socialisation process ● Formal rituals and celebrations ○ The ways in which a group celebrates key events that reflect important values or important ‘passages’ by members, such as promotion, completion of important projects, and milestones How Does an Organisational Culture Develop? ● When an organisation is founded, organisational culture forms and develops from the interaction between individual and the organisation. ● The degree to which an organisational culture, consciously and overtly rather than unconsciously and covertly, manifests itself influences how easily it can be managed and changed. ● When organisational culture changes, it involves changing surface level behavioural norms and artifacts, it can occur with relative ease. However, at the deepest levels, namely assumptions, ideologies, and human nature, it is very difficult and time consuming to create/change organisational culture Levels of Organisational Culture ● Artifacts ○ This includes all the phenomena that one sees and feels when one encounters a new group with an unfamiliar culture. ○ It includes the visible products of the group, such as the architecture of its physical environment, its artistic creations, its style, clothing, manners of address, myths and stories told about the organisation, its published list of values, its observable rituals and ceremonies, etc. ● Espoused values and beliefs ○ Espoused beliefs and values, according to Schein, are shared ideals and theories which may or may not actually guide behaviour. ○ Espoused beliefs are the guiding principles that individuals and organisations aspire to and may be found in statements of goals or philosophies. ○ Espoused beliefs may or may not be congruent with behaviour or theories in use. ○ Awareness of inconsistencies between espoused beliefs and personal behaviour can create internal conflict, and force individuals to alter either their beliefs or their behaviour. ■ Eg - Many companies say they value integrity, but, in reality, their employees consistently lie, cheat and steal to make a profit. ● Underlying assumptions ○ Schein defines the core of an organisational culture as being the underlying assumptions that members tend to share and take for granted. ○ The latter assumptions (taken for granted) are reflexive and therefore generally unquestioned or unexamined. ○ Basic assumptions are generalisations derived from past experiences of the individual which consist of internalised perceptions of the nature of persons or objects (including ideas) in the work environment. ○ The generalisations prescribe how to relate to people in various roles and how to act in given circumstances. ○ While basic assumptions are held by all individuals, they are covert and typically escape the conscious awareness of individuals. ○ These conceptions held by individuals, hidden beneath the surface, exert a powerful controlling force over professional behaviour . ○ Schein (1983) stresses the importance of self reflection in discovering one’s generalised assumptions and making them explicit. ■ He identifies self reflection as a key component of an effective professional practice. ■ Professional reflection is an underutilised tool which has the potential for helping the individuals to examine the congruence between their knowledge, their values and their assumptions. Theories of Organisational Culture ● Denison (1990) identifies four basic views of organisational culture that can be translated into four distinct hypotheses: ○ The Consistency Hypothesis ■ The idea that a common perspective, shared beliefs and communal values among the organisational participants would enhance internal coordination and promote meaning and a sense of identification on the part of its members. ○ The Mission Hypothesis ■ The idea that a shared sense of purpose, direction, and strategy would coordinate and galvanize organisational members toward collective goals. ○ The Involvement/Participation Hypothesis ■ The idea that involvement and participation would contribute to a sense of responsibility and ownership and, hence, organisational commitment and loyalty. ○ The Adaptability Hypothesis ■ The idea that norms and beliefs that enhance an organisation’s ability to receive, interpret, and translate signals from the environment into internal organisational and behavioural changes would promote its survival, growth, and development. Dominant Cultures, Subcultures and Countercultures ● Smaller firms often have a single dominant culture with a unitary set of shared actions, values, and beliefs. ● Larger organisations contain several subcultures as well as one or more counter cultures. ● This is the overall organisational culture, as expressed by the core values held by the majority of the organisation’s members. When people are asked to portray an organisation’s culture, they normally describe the dominant culture: a macro view that gives the organisation its distinct personality. Subcultures ○ Subcultures are groups of individuals with a unique pattern of values and philosophy that is not inconsistent with the organisation’s dominant values and philosophy (Schein 1985). ○ These subsets of the overall culture tend to develop in larger organisations to reflect the common problems, situations, or experiences that are unique to members of certain departments or geographical areas. The sub culture retains the core values of the dominant culture but modifies them to reflect its own distinct situation. Strong sub cultures are often found in high performance task forces, teams, and special project groups in organisations. ■ For example, there are strong subcultures of stress engineers and liaison engineers in the Boeing Renton Plant and in most of the subunits in the Defence Forces in India. ○ Highly specialised groups must solve knotty technical issues to ensure that Boeing planes are safe. Though distinct, these groups of engineers share in the dominant values culture? of Boeing. ○ Every large organisation imports potentially important sub cultural groupings when it hires employees from the larger society. Countercultures ○ Counter cultures have a pattern of values and a philosophy that reject the surrounding culture (Agor, 1989). ○ Within an organisation, mergers and acquisitions may produce counter cultures. Employers and managers of an acquired firm may hold values and assumptions that are quite inconsistent with those of the acquiring firm. This is known as the ‘clash of corporate cultures.’ When Coca-Cola bought Columbia Pictures, the soft-drink company found out too late that the picture business was quite different from selling beverages. It sold Columbia, with its unique corporate culture, to Sony rather than fight a protracted clash of cultures (Bazerman, 1994). ○ In India, for instance, subcultures and countercultures may naturally form, based on caste, gender, generation, family social status or geographic location. ○ In Japanese organisations, sub cultures are often formed, based on the date of graduation from a university, gender, or geographic location. ○ In European firms, ethnicity and language play an important part in developing sub cultures, as does gender. ○ In many less developed nations, language, education, religion, or family social status are often grounds for forming societal popular subcultures and countercultures. Difficulties related to Importing Groupings There are three primary difficulties with importing groupings from the larger societies, and it affects the relationship/relevance of subgroups with the organisation as a whole. ○ First, subordinated groups, such as members of a specific religion or ethnic group, are likely to form into a counter culture and work more diligently to change their status than to better the firm. ○ Second, the firm may find it extremely difficult to cope with broader cultural changes. For instance, in India, the expected treatment of women, minorities, and the disabled has changed dramatically over the last 20 years. ■ Firms that merely accept old customs and prejudices have experienced a greater loss of key personnel and increased communications difficulties, as well as greater interpersonal conflict, than have their more progressive counterparts. ○ Third, firms that accept and build on natural divisions from the larger culture may find it extremely difficult to develop sound international operations. Beginning Organisational Culture The ultimate source of an organisation’s culture is its founder(s). Founders have a vision of what the organisation should be, and they are unconstrained by previous customs or ideologies. The new organisation’s small size facilitates the founder’s imposition of his/her vision on all organisational members. Founders create culture in three ways: Employees selection Founders hire and keep only those employees who think and feel the same as the founders do. Socialisation Founders indoctrinate and socialise their employees toward the founders’ way of thinking and feeling. Modeling The founder acts as a role model and encourages employees to identify with him/her, and to internalise the his/her beliefs, values, and assumptions. Any organisational success is attributed to the founder’s vision, attitudes, and behaviour. In a sense, the organisation becomes an extension of the founder’s personality.Sustaining Organisational Culture Sustaining Organisational Culture Organisations serve to maintain it by giving employees a similar set of experiences. These practices include the selection process, performance evaluation criteria, training and development activities, and promotional procedures: those who support the culture are rewarded and those who do not are penalised. Employee selection The selection process needs to identify potential employees with relevant skill sets; one of the more critical facets of this process is ensuring that those selected have values that are consistent with those of the organisation. Employees whose values and beliefs are misaligned with those of the organisation tend to not be hired, or self-select out of the applicant pool. Actions of top management The verbal messages and actions of top management establish norms of behaviour throughout the organisation. These norms include the desirability of risk taking, level of employee empowerment, appropriate attire, and outlining successful career paths. Employee socialisation New employees must adapt to organisational culture in a process called socialisation. While socialisation continues throughout an employee’s career, the initial socialisation is most critical. There are three stages in initial socialisation. The success of this socialisation would affect employee productivity, commitment, and turnover. Changing Organisational Culture To change a culture, one has to change paradigms. According to Osborne and Plastrik, ‘the first thing you have to do is get people to let go of their old assumptions’. In science, the key is what Kuhn calls ‘anomalies’-problems the old paradigm cannot solve, realities it cannot explain, facts it cannot admit to be true. As these anomalies pile up, people begin to lose faith in the old paradigm. Thus, the manager needs to develop a change strategy which will: ● Introduce anomalies and help people to perceive them ● Provide a clearly defined new paradigm ● Build faith in the new paradigm ● Help people let go of the old paradigm ● Give people time in the neutral zone Give people touchstones ● Provide a safety net This requires that the whole plan be implemented at once. People begin to let go of their old paradigms when they run into experiences, facts, and feelings that cannot be explained by the old set of assumptions. These anomalies provoke ‘dissonance’ - conflicts between what one has experienced and what one knows to be possible. Often people cope by refusing to see the anomalies. When anomalies appear, they immediately define them as something else. If they are able to retreat to another part of the organisation and find support for their resistance, it is unlikely that the culture will ever change in the direction that the management has chosen. Every paradigm shift is ultimately a leap of faith and for those who have faith only in the old culture, there is likely to be a great deal of anxiety about who to trust and where they would land. To build people’s faith in a new culture, one must first earn their trust. None of us put our faith in people we don’t trust. We must then prove to them that others who have made the leap before them have flourished, and to assure them that they too would flourish in the new culture. A paradigm shift begins with an ending. It begins when people let go of their former worldview—a frightening process that creates much of the resistance to change. What this means is that in a transformation of culture, the management must be prepared to articulate the new culture completely, and to change the world abruptly. An abrupt change requires that there be plans, recipes, rules, instructions, which are the principal bases for the specificity of behaviour and an essential condition for governing it. Change is a time of uncertainty. Uncertainty causes anxiety. Managers should limit uncertainty, not by ‘easing into a new programme’, but by being explicit about expectations. Like them or not, knowing the new expectations and how they would be measured relieves uncertainty, and, for most, diminishes anxiety.