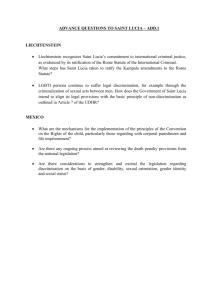

Clinical Gerontologist ISSN: 0731-7115 (Print) 1545-2301 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wcli20 Vida Calma: CBT for Anxiety with a SpanishSpeaking Hispanic Adult Katherine Ramos, Jose Cortes, Nancy Wilson, Mark E. Kunik & Melinda A. Stanley To cite this article: Katherine Ramos, Jose Cortes, Nancy Wilson, Mark E. Kunik & Melinda A. Stanley (2017) Vida Calma: CBT for Anxiety with a Spanish-Speaking Hispanic Adult, Clinical Gerontologist, 40:3, 213-219, DOI: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1292978 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1292978 Published online: 03 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 858 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wcli20 CLINICAL GERONTOLOGIST 2017, VOL. 40, NO. 3, 213–219 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1292978 NEW AND EMERGING PROFESSIONALS Vida Calma: CBT for Anxiety with a Spanish-Speaking Hispanic Adult Katherine Ramos, PhDa,b, Jose Cortes, BAc,d, Nancy Wilson, MA, MSWc,d, Mark E. Kunik, MD, MPHd,c,e, and Melinda A. Stanley, PhDd,c,e a Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; bDuke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA; cBaylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA; dMichael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Texas, USA; eVA South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Background: Hispanic adults aged 55 years and older are the fastest growing ethnic minority group in the United States facing significant mental health disparities. Barriers in accessing care have been attributed to low income, poor education, language barriers, and stigma. Cultural adaptations to existing evidence-based treatments have been encouraged to improve access. However, little is known about mental health treatments translated from English to Spanish targeting anxiety among this Hispanic age group. Objctive: This case study offers an example of how an established, manualized, cognitive-behavioral treatment for adults 55 years and older with generalized anxiety disorder (known as “Calmer Life”) was translated to Spanish (“Vida Calma”) and delivered to a monolingual, Hispanic 55-year-old woman. Results: Pre- and post-treatment measures showed improvements in symptoms of anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction. Conclusion: Findings suggest Vida Calma is a feasible treatment to use with a 55-year-old Spanishspeaking adult woman. Clinical Implications: Vida Calma, a Spanish language version of Calmer Life, was acceptable and feasible to deliver with a 55-year-old participant with GAD. Treatment outcomes demonstrate that Vida Calma improved the participant’s anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction. Anxiety; case reports; cognitive-behavior therapy; Hispanic adults Introduction Hispanic adults (aged 55 years and older) are the fastest growing ethnic minority group in the United States, with fewer than 24% initiating mental health treatment when needed (Jimenez, Cook, Bartels, & Alegría, 2013). Low mental health care access and utilization in this population presents a significant health disparity (Barrio et al., 2008). Contributors to limited access include low income, poor education, language barriers, and cultural stigma (Aranda & Lincoln, 2011; Hansen & Aranda, 2012). Limited English proficiency, in particular, is associated with poorer access to healthcare (DuBard & Gizlice, 2008) and increased risk for psychological distress (Kim et al., 2011). Hispanic adults who are 55 years old or older, second to non-Hispanic whites, have the highest lifetime prevalence for mood (13.9%) or anxiety disorders (15.2%) compared with other minority groups (Woodward et al., 2012). One-year prevalence data show similar trends; for example, among Hispanic (in the age category of 55+) having a past-year mood disorder is 9.48% and for an anxiety disorder it is 13.59% (Reynolds, Pietrzak, El-Gabalawy, Mackenzie, & Sareen, 2015). Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is the most common psychiatric condition among Hispanics over 55 years of age, with a lifetime prevalence of 6.2% (Woodward et al., 2012). Interventions designed to improve mental health access for Hispanic adults over 55 have targeted depression (Areán et al., 2005; Ell et al., 2010; Hinton & Areán, 2008), but interventions have yet to address anxiety in this age group. In a randomized control trial across four different clinic sites, Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was found effective for younger Hispanic adults with panic disorder, GAD, social anxiety disorder or posttraumatic disorder (PTSD) (Chavira et al., 2014); although treatment was most effective for individuals who are primarily English-speaking and more acculturated. CONTACT Katherine Ramos, PhD Katherine.Ramos@va.gov GRECC (182), Durham VA Medical Center, 508 Fulton Street, Durham, NC 27705, USA. Color versions of the figure in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/wcli. This article is not subject to U. S. copyright law. 214 K. RAMOS ET AL. Among adults aged 55 years and older with GAD, CBT demonstrates significant reductions in anxiety symptoms relative to waitlist conditions or usual care (Gonçalves & Byrne, 2012; Gould, Coulson, & Howard, 2012, 2014; Stanley et al., 2009; Thorp et al., 2009). CBT for late-life GAD showed positive effects (e.g., improvement in GAD severity and reduced symptoms of depression) among ethnic and racial minorities, mostly African Americans (Stanley et al., 2016), but research has yet to examine outcomes with Spanish-speaking Hispanic adults over 55 years of age. This case study describes the implementation of an established manualized CBT for GAD known as “Calmer Life” for a Spanish-speaking 55-year old adult woman. The Spanish-language version of the intervention is called “Vida Calma.” Outcomes of interest included generalized anxiety, depression, insomnia, and life satisfaction. Exit interview feedback, number of sessions and completed home practice assignments were used to evaluate feasibility and acceptability of treatment. Case Study Calmer Life Program Overview and Spanish Adaptation Calmer life is a 3-month (up to 12 sessions) modular CBT targeting GAD symptoms. Delivery method is flexible, with the first two to three sessions completed in-person and the remainder delivered either in-person or by telephone. Three initial sessions address anxiety awareness, diaphragmatic breathing, and use of calming statements. Participants subsequently select five elective modules covering exposure, behavioral activation, relaxation skills, problem solving and cognitive re-structuring. Community resources to address basic needs/personal care are offered and discussed with the participant. Unique to this intervention is the option to include religious/spiritual (R/S) beliefs. Previous participants have expressed satisfaction with attention to R/S beliefs in treatment, and preliminary outcomes from the English-language version are positive (Shrestha et al., 2012; Stanley et al., 2016). Translation of Calmer Life to Vida Calma involved a three-stage process. First, a professional translation service was used to translate two treatment manuals (one R/S-based, the other secular) and a provider manual. The primary author (KR), fluent in Spanish, worked closely with the service. Of note, session content of the English version of Calmer Life is at an 8th grade reading level. However, for Vida Calma, session content was translated to a sixth-grade reading level to align with state data and education-level guidelines among the Hispanic community living in an urban city in the Southern U.S. (Department of Health and Human Services, and Hispanic Health Coalition, 2013). Second, upon receipt of translated materials, the first author (KR), together with a bilingual consumer and bilingual Master’s-level provider (who subsequently served as an independent evaluator for pre- and post-intervention measures), reviewed treatment content and addressed discrepancies in language use. Third, (KR) secured Spanish versions of diagnostic and pre- and post-treatment measures, including the Structured Diagnostic Interview for the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (SCID; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; García-Campayo et al., 2010; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., 2009), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Fernandez-Mendoza et al., 2012; Morin, 1993), and the Satisfaction with Life scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). The lead author translated an exit interview used in prior English-language studies (Shrestha et al., 2012; Stanley et al., 2016), and trained the Master’s-level provider to deliver baseline and posttreatment measures. The exit interview contained detailed questions comprising four main areas: (a) personal experiences about participating in the program (e.g., having the option to add R/S to the Vida Calma skills; helpful and least useful components of the program, satisfaction with number of sessions received, and suggestions to improve the program), (b) personal use of the Vida Calma skills, (c) satisfaction with service delivery locale or format (e.g., having sessions offered at home, a partner site or via telephone), and (d) general experiences with the Vida Calma provider, overall satisfaction with the program, and confidence in continued used of the Vida Calma skills. CLINICAL GERONTOLOGIST Participant Demographic Information Initial Assessment Lucia was friendly and pleasant but presented with an anxious disposition. She reported experiencing anxiety all her life, with worsened symptoms in the last 2 years. Lucia denied specific precipitating factors, although she endorsed continued arduous work hours and changes in physical health and stamina as contributing factors to her worry. Her baseline symptoms met criteria for GAD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), as assessed by the SCID. She denied needing resources for basic needs. In the past 6 months, she reported feeling restless, irritable, and tense. She often tired easily and had difficulty focusing, and trouble falling and staying asleep. She endorsed moderate symptoms of worry and anxiety regarding minor matters, work, finances, social relationships, and personal health. Lucia worried about her financial stability (subsequently perpetuating low mood), her declining physical health (e.g., chronic pain, reduced mobility for heavy lifting and undesired weight gain), and feeling overwhelmed by daily errands/tasks. At the start of treatment, she also expressed sadness, tearfulness, decreased interest in previously enjoyed activities, and worry over her friend’s terminal illness. During the pretreatment assessment, Lucia scored in the moderately severe to severe range on measures of anxiety (GAD-7 = 15) and depression (PHQ8 = 16). She scored in the subthreshold range for 35 30 25 Scores Lucia was a 55-year-old Hispanic female native of South America who immigrated to the United States in her thirties. She was living with her only adult son during participation. She was divorced for the last 15 years from a verbally and physically abusive exhusband who she reported suffered from severe alcohol abuse. Lucia worked fulltime as a housemaid and provided weekend caregiving to older adults as a volunteer. She also ran a support group for victims of domestic violence at her local church. Lucia denied any prior anxiety treatment (and denied clinically significant symptoms of PTSD related to previous abuse). She was not taking any medications. Lucia self-referred to the intervention after attending a community outreach presentation. 215 20 Baseline 15 3 Month 10 5 0 GAD PHQ ISI SWLS Assessment Measures Figure 1. Treatment outcome scores. This figure illustrates Assessment scores of anxiety, depression insomnia, and life satisfaction at baseline and three-month follow-up. (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale [GAD-7; Range 0–21]), depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-8 [PHQ-8; Range 0–24]), sleep (Insomnia Severity Index [ISI; Range 0–28]), and life satisfaction (Satisfaction With Life Scale [SWLS; Range 5–35]). Note, higher scores for GAD, PHQ, and ISI = higher severity in symptoms. Higher scores in SWLS = higher life satisfaction. insomnia (ISI = 14) and in the average range for life satisfaction (SWL = 22) (see Figure 1). Module Selection The therapist provided appropriate recommendations for CBT modules, using a protocol algorithm based on the English version of Vida Calma (Shrestha et al., 2012). This algorithm used baseline scores to guide provider recommendations and collaborative decision-making about elective skills. Lucia began treatment with core skills addressing anxiety awareness, deep breathing, and calming thoughts. Lucia then chose the following elective skills: changing behavior to manage depression, problem solving and learning to relax (this last skill could not be completed due to participant time constraints). To accommodate Lucia’s schedule and access to treatment, she completed all sessions (except two) by phone. Inclusion of Religious Affiliation Into Treatment Lucia identified as Catholic. She grew up with a strong religious faith and belief in a higher power. She was active in her church community and often used her religion as a source of comfort. Lucia chose to include her religious beliefs in treatment. 216 K. RAMOS ET AL. Session Descriptions and Treatment Sessions 1 and 2 Session 1 focused on anxiety awareness and a discussion of Lucia’s life values, treatment goals, and motivation for change. Her life values included being a good person (e.g., caring for a friend diagnosed with cancer), caring for her health and well-being, having financial stability, and good quality of life. The first session provided psychoeducation around anxietyrelated thoughts, behaviors and physical symptoms, and the option of including spirituality in treatment. A list of community resources was also provided. Session 2 included assessment of Lucia’s beliefs about Catholicism. She exhibited a strong belief in God and viewed the Catholic church as a safe haven from difficult life circumstances. From her R/S perspective, it was also important that Lucia treat others with compassion and empathic understanding. Lucia, active in her church, attended weekly service and prayed daily. She consistently prayed to God for “help and bravery” to overcome difficult obstacles in her life related to her health concerns (e.g., reducing pain and losing weight) and financial security. Lucia enjoyed reading the Bible with selected verses that she perceived help answer her prayers. During Session 2, Lucia learned diaphragmatic breathing. She was encouraged to focus on a spiritual word or image while practicing. Lucia chose the words Dios Mio!, meaning “My God!” in English. This phrasing aligned with Lucia’s special connection and relationship with a higher power. She found this skill helpful when she worried about her friend’s declining health and as another source of connecting to God. Session 3 Lucia was introduced to calming statements to decrease the effects of anxiety. In this skill, participants can choose a combination of both spiritual and nonspiritual statements. Lucia identified the following statements: “I can do what I have to do in spite of my worry or stress,” and “My worry or stress won’t hurt me.” A specific spiritual statement chosen by Lucia was: “I am thankful to God for this opportunity to grow for myself.” Lucia’s friend passed away the week prior, and she used breathing techniques for comfort while attending the funeral. As she practiced calming statements in session, she also offered examples of when she could utilize the skill. For example, Lucia later described using calming statements to reduce anxiety when organizing church events and when needing to assert her opinions on personally important matters. Sessions 4 and 5 These two sessions addressed behavioral activation for depression. Lucia experienced greater severity in depressive symptoms as her financial situation worsened. Given her need to secure additional jobs, self-care became increasingly limited. She worried about having time to accomplish daily tasks and hobbies. Additionally, Lucia often wondered whether seeking treatment was “too self-focused and selfish.” These anxieties increased her depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and social isolation. Lucia also had decreased appetite, discontinued social gatherings (e.g., eating with friends, music concerts), and found less pleasure in previously enjoyed hobbies. The therapist and Lucia discussed the link between her lower mood and decreased frequency of pleasant activities. Afterward, Lucia was encouraged to consider activities she could pursue to improve her mood. Illustratively, she was encouraged to attend church and community events. When she followed through, she noticed improvements in her mood and anxiety. During Session 5, Lucia reported cooking for herself, attending church more frequently and walking for exercise and relaxation. She also began discussions about life-meaning and her future. For example, Lucia discussed having interest in completing her GED and wanting to prioritize her time to feel better. She initiated reading the Bible with greater frequency, practicing yoga, and eating out with friends. Lucia found behavioral activation skills helpful. Her participation in pleasant events subsequently translated to improvements in her time management and boundary-setting with work and church commitments. Lucia shared relying on calming statements and diaphragmatic breathing while envisioning images of “God” or “Jesus” as motivators for behavior change. Sessions 6 and 7 Session 6 focused on problem solving. In this session, Lucia learned about the effects of stress, CLINICAL GERONTOLOGIST worry and anxiety on her ability to identify/solve problems in daily-living. She also learned steps to identify a problem, consider all viable solutions, and then decide and choose a course of action. Lucia identified household activities (gardening) she was unable to complete due to time constraints. She listed possible solutions such as asking someone for help and/or paying for gardening services. For each possible solution, Lucia offered examples of advantages and disadvantages. Regarding gardening, Lucia decided to take time after work to plant flowers she always wanted in her backyard. She developed action plans with times, days of the week, and frequency that she could dedicate to her efforts. She also desired to keep her home cleaner than its current state, and she decided to prioritize the rooms she would like cleaned first and created an organized chore list to maintain her efforts. Throughout, Lucia presented with a determined and resourceful outlook. Lucia was also encouraged to consider using previously learned skills as coping resources in her problemsolving activities. Session 7 served as a summary and review of completed Vida Calma skills. This session also provided Lucia with opportunities to discuss future anxiety-provoking situations and the skills she would use to reduce her anxiety. Examples included use of deep breathing during social events with large crowds and calming statements when feeling financially stressed. 217 perceiving others noticing her sleep difficulties were impairing her quality of life (2-point increase). A possible explanation for an increase in insomnia symptoms could be her continued anxiety about finances. During her participation in treatment, financial stability was a consistent source of anxiety that may have worsened for Lucia due to unanticipated work shift changes and pay cuts. Overall, however, Lucia experienced and recognized positive changes in her life and her ability to self-soothe when anxious or distressed. Exit Interview Lucia highly regarded her participation with Vida Calma. In particular, she deeply appreciated including her R/S beliefs in treatment. She also expressed that continued practice of the Vida Calma skills afforded her personal growth (e.g., efficacy and patience in making better decisions around work– life balance), and relaxation by using deep breathing and calming statements, in addition to flexibility in daily living by using her problem-solving skills (e.g., managing her time for self-care while also completing needed household responsibilities). Moreover, by engaging in pleasant events (i.e., behavioral activation), her overall mood improved and feelings of depression significantly decreased. In her own words, Lucia rated the program as “very helpful” and mentioned feeling “very sure” that she would continue to use the skills in the future. Assessment and Outcomes Discussion At 3 months, Lucia responded to the same baseline measures. Lucia’s assessment scores are presented in Figure 1. By 3 months, Lucia reported meaningful improvements in anxiety and depression. Specifically, her symptoms were below the clinical threshold for mild anxiety (GAD-7 = 5); her depression symptoms (PHQ-8 = 5); decreased from severeto-mild severity levels. Lucia also reported improved life satisfaction (SWLS = 30), though she endorsed an increase in insomnia symptoms (ISI = 19, raw change of 4+ points from pre- to post-intervention). Upon further review, specific symptoms that led an increase in pre- to post-treatment scores on the ISI included: waking up too early (1-point increase), dissatisfaction with current sleep patterns (2-point increase), and This case study describes successful implementation of Vida Calma, a manualized intervention for the treatment of GAD for a 55-year-old Spanish-speaking adult. The intervention was well received, and treatment outcomes indicated improvement in anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction. Previous studies have demonstrated positive outcomes in the delivery of mental health treatments for depression among Hispanic adults aged 55 years and older. However, none have examined treatment outcomes of those who are monolingual and have a diagnosable anxiety disorder. Despite promising results, including Lucia’s positive reception of Vida Calma, she did not complete one last elective module that could have influenced improved symptom reduction at 218 K. RAMOS ET AL. the end of treatment. Additional study limitations to be addressed in future studies include: improving translation equivalence via backward translation methods and performing post-intervention followup assessments to address maintained gains from program participation. Further study is needed to address treatment efficacy and effectiveness. Additionally, research detailing implementation of this treatment with nonreligious Hispanic adults may also offer further insights about treatment feasibility. Given the obvious and yet unmet mental health needs of Hispanic adults over the age of 55 (Barrio et al., 2008), the hope of this study is to offer an initial suggestion of the acceptability and feasibility of delivering the Calmer Life intervention translated to Spanish and titled: Vida Calma. Clinical Implications ● Vida Calma, a Spanish language version of Calmer Life, was acceptable and feasible to deliver with a 55-year-old participant with GAD. ● Treatment outcomes demonstrate that Vida Calma improved the participant’s anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction. Funding This material is the result of work supported by the use and resources of the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. government or Baylor College of Medicine. References American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. Aranda, M. P., & Lincoln, K. (2011). Financial strain, negative interaction, coping styles, and mental health among low-income Latinos. Race and Social Problems, 3, 280–297. doi:10.1007/s12552-011-9060-4 Areán, P. A., Ayalon, L., Hunkeler, E., Lin, E. H., Tang, L., Harpole, L., . . . Unützer, J. (2005). Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Medical Care, 43, 381–390. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1 Barrio, C., Palinkas, L. A., Yamada, A. M., Fuentes, D., Criado, V., Garcia, P., & Jeste, D. V. (2008). Unmet needs for mental health services for Latino older adults: Perspectives from consumers, family members, advocates, and service providers. Community Mental Health Journal, 44, 57–74. doi:10.1007/s10597-007-9112-9 Chavira, D. A., Golinelli, D., Sherbourne, C., Stein, M. B., Sullivan, G., Bystritsky, A., . . . Bumgardner, K. (2014). Treatment engagement and response to CBT among Latinos with anxiety disorders in primary care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 392–403. doi:10.1037/a0036365 Department of Health and Human Services (City of Houston), & Hispanic Health Coalition. (2013). Population growth, demographics, chronic disease and health disparities [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://www.hous tontx.gov/health/chs/HispanicHealthDepBooklet.pdf Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 DuBard, C. A., & Gizlice, Z. (2008). Language spoken and differences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among U.S. Hispanics. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 2021–2028. doi:10.2105/ AJPH.2007.119008 Ell, K., Katon, W., Xie, B., Lee, P. J., Kapetanovic, S., Guterman, J., & Chou, C. P. (2010). Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 33, 706–713. doi:10.2337/ dc09-1711 Fernandez-Mendoza, J., Rodriguez-Muñoz, A., Vela-Bueno, A., Olavarrieta-Bernardino, S., Calhoun, S. L., Bixler, E. O., & Vgontzas, A. N. (2012). The Spanish version of the Insomnia Severity Index: A confirmatory factor analysis. Sleep Medicine, 13, 207–210. doi:10.1016/j. sleep.2011.06.019 García-Campayo, J., Zamorano, E., Ruiz, M. A., Pardo, A., Pérez-Páramo, M., López-Gómez, V., . . . Rejas, J. (2010). Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 1–11. doi:10.1186/14777525-8-8 Gonçalves, D. C., & Byrne, G. J. (2012). Interventions for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.010 Gould, R. L., Coulson, M. C., & Howard, R. J. (2012). Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in older people: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60, 218–229. doi:10.1111/j.15325415.2011.03824.x CLINICAL GERONTOLOGIST Hansen, M. C., & Aranda, M. P. (2012). Sociocultural influences on mental health service use by Latino older adults for emotional distress: Exploring the mediating and moderating role of informal social support. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 2134–2142. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.029 Hinton, L., & Areán, P. A. (2008). Epidemiology, assessment, and treatment of depression in older Latinos. In S. A. Aguilar-Gaxiola, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Depression in Latinos: Assessment, treatment, and prevention (pp. 277–298). New York: Springer Science. Jimenez, D. E., Cook, B., Bartels, S. J., & Alegría, M. (2013). Disparities in mental health service use of racial and ethnic minority elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61, 18–25. doi:10.1111/jgs.12063 Kim, G., Worley, C. B., Allen, R. S., Vinson, L., Crowther, M. R., Parmelee, P., & Chiriboga, D. A. (2011). Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 1246–1252. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03483.x Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114, 163–173. doi:10.1016/j. jad.2008.06.026 Morin, C. M. (1993). Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press. Reynolds, K., Pietrzak, R. H., El-Gabalawy, R., Mackenzie, C. S., & Sareen, J. (2015). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in US older adults: Findings from a nationally representative survey. World Psychiatry, 14, 74–81. doi:10.1002/wps.20193 Shrestha, S., Armento, M. E., Bush, A. L., Huddleston, C., Zeno, D., Jameson, J. P., . . . Stanley, M. A. (2012). Pilot finding from a community-based treatment program for late-life anxiety. The International Journal of Person Centered Medicine, 2, 400–409. 219 Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 Stanley, M. A., Wilson, N., Shrestha, S., Amspoker, A. B., Armento, M., Cummings, J. P., . . . Kunik, M. E. (2016). Calmer Life: A culturally tailored intervention for anxiety in underserved older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24, 648–658. doi:10.1016/j. jagp.2016.03.008 Stanley, M. A., Wilson, N. L., Amspoker, A. B., KrausSchuman, C., Wagener, P. D., Calleo, J. S., . . . Masozera, N. (2014). Lay providers can deliver effective cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized trial. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 391–401. doi:10.1002/da.22239 Stanley, M. A., Wilson, N. L., Novy, D. M., Rhoades, H. M., Wagener, P. D., Greisinger, A. J., & Kunik, M. E. (2009). Cognitive behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder among older adults in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 1460–1467. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.458 Thorp, S. R., Ayers, C. R., Nuevo, R., Stoddard, J. A., Sorrell, J. T., & Wetherell, J. L. (2009). Meta-analysis comparing different behavioral treatments for late-life anxiety. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 105–115. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818b3f7e Woodward, A. T., Taylor, R. J., Bullard, K. M., Aranda, M. P., Lincoln, K. D., & Chatters, L. M. (2012). Prevalence of lifetime DSM-IV affective disorders among older African Americans, Black Caribbeans, Latinos, Asians and Non-Hispanic Whites. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 816– 827. doi:10.1002/gps.2790