94638433-Solution-Manual-Managerial-Accounting-Hansen-Mowen-8th-Editions-ch-4

advertisement

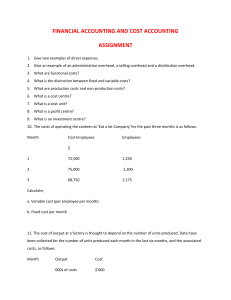

CHAPTER 4 ACTIVITY-BASED PRODUCT COSTING QUESTIONS FOR WRITING AND DISCUSSION 1. Unit costs provide essential information needed for inventory valuation and preparation of income statements. Knowing unit costs is also critical for many decisions such as bidding decisions and accept-or-reject special order decisions. represent a significant proportion of total overhead costs. 8. Low-volume products may consume nonunit-level overhead activities in much greater proportions than indicated by a unit-level cost driver and vice versa for high-volume products. If so, then the low-volume products will receive too little overhead and the high-volume products too much. 2. Cost measurement is determining the dollar amounts associated with resources used in production. Cost assignment is associating the dollar amounts, once measured, with units produced. 9. If some products are undercosted and others are overcosted, a firm can make a number of competitively bad decisions. For example, the firm might select the wrong product mix or submit distorted bids. 3. An actual overhead rate is rarely used because of problems with accuracy and timeliness. Waiting until the end of the year to ensure accuracy is rejected because of the need to have timely information. Timeliness of information based on actual overhead costs runs into difficulty (accuracy problems) because overhead is incurred nonuniformly and because production also may be nonuniform. 4. For plantwide rates, overhead is first collected in a plantwide pool, using direct tracing. Next, an overhead rate is computed and used to assign overhead to products. 5. First stage: Overhead is assigned to production department pools using direct tracing, driver tracing, and allocation. Second stage: Individual departmental rates are used to assign overhead to products as they pass through the departments. 10. Nonunit-level overhead activities are those overhead activities that are not highly correlated with production volume measures. Examples include setups, material handling, and inspection. Nonunit-level cost drivers are causal factors — factors that explain the consumption of nonunit-level overhead. Examples include setup hours, number of moves, and hours of inspection. 11. Product diversity is present whenever products have different consumption ratios for different overhead activities. 12. An overhead consumption ratio measures the proportion of an overhead activity consumed by a product. 13. Departmental rates typically use unit-level cost drivers. If products consume nonunitlevel overhead activities in different proportions than those of unit-level measures, then it is possible for departmental rates to move even further away from the true consumption ratios, since the departmental unit-level ratios usually differ from the one used at the plant level. 14. Agree. Prime costs can be assigned using direct tracing and so do not cause cost distortions. Overhead costs, however, are not directly attributable and can cause distortions. For example, using unit-level activity drivers to trace nonunit-level overhead costs would cause distortions. 6. Departmental rates would be chosen over plantwide rates whenever some departments are more overhead intensive than others and if certain products spend more time in some departments than they do in others. 7. Plantwide overhead rates assign overhead to products in proportion to the amount of the unit-level cost driver used. If the products consume some overhead activities in different proportions than those assigned by the unit-level cost driver, then cost distortions can occur (the product diversity factor). These distortions can be significant if the nonunit-level overhead costs 75 ties are those that are performed each time a batch of products is produced. Product-level or sustaining activities are those that are performed as needed to support the various products produced by a company. Facilitylevel activities are those that sustain a factory’s general manufacturing process 15. Activity-based product costing is an overhead costing approach that first assigns costs to activities and then to products. The assignment is made possible through the identification of activities, their costs, and the use of cost drivers. 16. An activity dictionary is a list of activities accompanied by information that describes each activity (called attributes) 20. Rates can be reduced by building a system that approximates the cost assignments of a fully specified ABC system. One way to do this is by using only the most expensive activities to assign costs. If the most expensive activities represent a large percentage of the total costs, then most of the costs are assigned using a cause-and-effect relationship, thus creating a good level of accuracy while reducing the complexity of the ABC system. 17. A primary activity is consumed by the final cost objects such as products and customers, whereas secondary activities are consumed by other activities (ultimately consumed by primary activities). 18. Costs are assigned using direct tracing and resource drivers. 19. Unit-level activities are those that occur each time a product is produced. Batch-level activi- 76 EXERCISES 4–1 1. Units produced Prime costs Overhead costs Unit cost: Prime Overhead Total Quarter 1 Quarter 2 Quarter 3 Quarter 4 Total 400,000 160,000 80,000 560,000 1,200,000 $8,000,000 $3,200,000 $1,600,000 $11,200,000 $24,000,000 $3,200,000 $2,400,000 $3,600,000 $2,800,000 $12,000,000 $20 8 $28 $20 15 $35 $20 45 $65 $20 5 $25 $20 10 $30 2. Actual costing can produce wide swings in the overhead cost per unit. The cause appears to be nonuniform incurrence of overhead and nonuniform production (seasonal production is a possibility). 3. First, calculate a predetermined rate: OH rate = $11,640,000/1,200,000 = $9.70 per unit This rate is used to assign overhead to the product throughout the year. Since the driver is units produced, $9.70 would be assigned to each unit. Adding this to the actual prime costs produces a unit cost under normal costing: Unit cost = $9.70 + $20.00 = $29.70 This cost is close to the actual annual cost of $30.00. 77 4–2 1. $27,000,000/90,000 = $300 per direct labor hour (DLH) 2. $300 × 91,000 = $27,300,000 3. Applied overhead Actual overhead Overrapplied overhead 4. Predetermined rates allow the calculation of unit costs and avoid the problems of nonuniform overhead incurrence and nonuniform production associated with actual overhead rates. Unit cost information is needed throughout the year for a variety of managerial purposes. $ 27,300,000 27,200,000 $ 100,000 4–3 1. Predetermined overhead rate = $4,500,000/600,000 = $7.50 per DLH 2. Applied overhead = $7.50 × 585,000 = $4,387,500 3. Applied overhead Actual overhead Underapplied overhead 4. Unit cost: Prime costs Overhead costs Total Units Unit cost $ 4,387,500 4,466,250 $ (78,750) $ 6,750,000 4,387,500 $ 11,137,500 ÷ 750,000 $ 14.85 78 4–4 1. Predetermined overhead rate = $4,500,000/187,500 = $24 per machine hour (MHr) 2. Applied overhead = $24 × 187,875 = $4,509,000 3. Applied overhead Actual overhead Overapplied overhead 4. Unit cost: Prime costs Overhead costs Total Units Unit cost $ 4,509,000 4,466,250 $ 42,750 $ 6,750,000 4,509,000 $ 11,259,000 ÷ 750,000 $ 15.01* *Rounded 5. Gandars needs to determine what causes its overhead. Is it primarily labor driven (e.g., composed predominantly of fringe benefits, indirect labor, and personnel costs), or is it machine oriented (e.g., composed of depreciation on machinery, utilities, and maintenance)? It is impossible for a decision to be made on the basis of the information given in this exercise. 79 4–5 1. Predetermined rates: Drilling Department: Rate = $600,000/280,000 = $2.14* per MHr Assembly Department: Rate = $392,000/200,000 = $1.96 per DLH *Rounded 2. Applied overhead: Drilling Department: $2.14 × 288,000 = $616,320 Assembly Department: $1.96 × 196,000 = $384,160 Overhead variances: Actual overhead Applied overhead Overhead variance 3. Drilling $602,000 616,320 $ (14,320) over Assembly $ 412,000 384,160 $ 27,840 under Unit overhead cost = [($2.14 × 4,000) + ($1.96 × 1,600)]/8,000 = $11,696/8,000 = $1.46* *Rounded 80 Total $ 1,014,000 1,000,480 $13,520 under 4–6 1. Activity rates: Machining = $632,000/300,000 = $2.11* per MHr Inspection = $360,000/12,000 = $30 per inspection hour *Rounded Unit overhead cost = [($2.11 × 4,000) + ($30 × 800)]/8,000 = $32,440/8,000 = $4.055 2. 4–7 1. Inspection hours Setup hours Machine hours Number of moves Scented Cards 0.20a 0.50b 0.25c 0.75d Regular Cards 0.80a 0.50b 0.75c 0.25d a. Total inspection hours = 200 (40+160); 40/200 for Scented and 160/200 for Regular b. Total Setup hours = 100 (50+50); 50/100 for Scented and 50/100 for Regular c. Total Machine hours = 800 (200+600); 200/800 for Scented and 600/800 for Regular d. Total Number of moves = 300 (225+75); 225/300 for Scented and 75/300 for Regular 2. The consumption ratios vary significantly from driver to driver. Using, for example, only machine hours to assign the overhead may create accuracy problems. Both setup hours and number of moves have markedly different consumption ratios. 4–8 1. Rates: Inspecting products: $2,000/200 = $10 per inspection hour Setting up equipment: $2,500/100 = $25 per setup hour Machining: $4,000/800 = $5 per machine hour Moving materials: $900/300 = $3.00 per move Note: The denominator is the total driver amount (sum of the demand of the two products). 81 2. Rate = Cost/hours Inspection hours = Cost/Rate = $2,000/$20 = 100 inspection hours 4–9 1. Normal Treating patients: $4.00 × 5,000 $4.00 × 20,000 Providing hygienic care: $5.00 × 5,000 $5.00 × 11,000 Responding to requests: $2.00 × 30,000 $2.00 × 50,000 Monitoring patients: $0.75 × 20,000 $0.75 × 180,000 Cost Assigned Intensive $ 20,000 $ 80,000 25,000 55,000 60,000 100,000 15,000 135,000 $370,000 $120,000 2. Nursing cost per patient day: $120,000/10,000 $370,000/8,000 Normal $12.00 Intensive $46.25 4–10 1. Yes. Because direct materials and direct labor are directly traceable to each product, their cost assignment should be accurate. 2. The consumption ratios for each (using machine hours and setup hours as the activity drivers) are as follows: Machining Setups 3. Elegant 0.10 0.50 Fina 0.90 (500/5,000 and 4,500/5,000) 0.50 (100/200 and 100/200) Elegant: (1.75 × $9,000)/3,000 = $5.25 per briefcase 82 Fina: (1.75 × $3,000)/3,000 = $1.75 per briefcase Note: Overhead rate = $21,000/$12,000 = $1.75 per direct labor dollar (or 175 percent of direct labor cost). There are more machine and setup costs assigned to Elegant than Fina. This is clearly a distortion because the production of Fina is automated and uses the machine resources much more than the handcrafted Elegant. In fact, the consumption ratio for machining is 0.10 and 0.90 (using machine hours as the measure of usage). Thus, Fina uses 9 times the machining resources as Elegant. Setup costs are similarly distorted. The products use an equal number of setup hours. Yet if direct labor dollars are used, then the Elegant briefcase receives three times more machining costs than the Fina briefcase. 4. Products tend to make different demands on overhead activities and this should be reflected in overhead cost assignments. Usually this means the use of both unit and nonunit-level activity drivers. In this example, there is a unit-level activity (machining) and a nonunit-level activity (setting up equipment). Machine rate: $18,000/5,000 = $3.60 per machine hour Setup rate: $3,000/200 = $15 per setup hour Costs assigned to each product: Machining: $3.60 × 500 $3.60 × 4,500 Setups: $15 × 100 Total Units Unit overhead cost Elegant $ 1,800 Fina $16,200 1,500 $ 3,300 ÷ 3,000 $ 1.10 83 1,500 $17,700 ÷ 3,000 $ 5.90 4-11 1. Resource Equipment Fuel Operating Labor* Total Unloading Counting Inspecting $12,000 $ 800 2,400 1,000 500 48,000 30,000 42,000 $30,000 $43,300 $63,400 *(0.40 × $120,000; 0.25 × $120,000; 0.35 × $120,000) 2. Direct tracing and driver tracing are used. When the resource is used only by one activity, then direct tracing is possible. When the activities are shared, as in the case of labor, then resource drivers must be used. 4–12 Activity dictionary: Activity Name Activity Description Primary/ Secondary Activity Driver Providing nursing care Satisfying patient needs Primary Nursing hours Supervising nurses Coordinating nursing activities Secondary Number of nurses Feeding patients Providing meals to patients Primary Number of meals Laundering bedding and clothes Cleaning and delivering clothes and bedding Primary Pounds of laundry Providing physical therapy Therapy treatments directed by physician Primary Hours of therapy Monitoring patients Using equipment to monitor patient conditions Primary Monitoring hours 84 4–13 1. Cost of labor (0.40 × $50,000) Forklift (direct tracing) Total cost of receiving $20,000 10,000 $30,000 2. Activity rates: Receiving: Setup: Grinding: Inspecting: $30,000/60,000 = $0.50 per part $60,000/300 = $200 per setup $90,000/18,000 = $5 per MHr $20,000/2,000 = $10 per inspection Subassembly A Overhead: Setup: $200 × 150 $200 × 150 Inspecting: $10 × 1,500 $10 × 500 Grinding: $5 × 7,200 $5 × 10,800 Receiving: $0.50 × 20,000 $0.50 × 40,000 Total costs assigned 3. Subassembly B $ 30,000 $ 30,000 15,000 5,000 36,000 54,000 10,000 $91,000 20,000 $109,000 Setup pool: $60,000 + [($60,000/$150,000) × $50,000] = $80,000 Grinding pool: $90,000 + [($90,000/$150,000) × $50,000] = $120,000 Pool rates: Setup = $80,000/300 = $266.67/setup Grinding = $120,000/18,000 = $6.67/ Mhr 85 Approximating assignment: Subassembly A Setup: $266.67 × 150 $266.67 × 150 Grinding: $6.67 × 7,200 $6.67 × 10,800 Total costs assigned 4. Subassembly B $40,000 $ 40,000 48,024 $88,024 72,036 $112,036 Error (Subassembly A) = ($91,000 - $88,024)/$91,000 = 0.033 Error (Subassembly B) = ($109,000 - $112,036)/$109,000 = - 0.028 The error is small and so the approach may be desirable as it reduces the complexity and size of the system, making it more likely to be accepted by management. 4–14 1. Unit-level activities: Batch-level activities: Product-level activities: Facility-level activities: Machining Setups and packing Receiving None 2. Activity rates: (1) Machining: $80,000/40,000 = $2 per MHr (2) Setups: $32,000/400 = $80 per setup (3) Receiving: $18,000/600 = $30 per receiving order (4) Packing: $48,000/3,200 = $15 per packing order Overhead assignment: Infantry Activity 1: $2 × 20,000 = $ 40,000 Activity 2: $80 × 300 = 24,000 Activity 3: $30 × 200 = 6,000 Activity 4: $15 × 2,400 = 36,000 Total $106,000 86 Special forces Activity 1: $2 × 20,000 = Activity 2: $80 × 100 = Activity 3: $30 × 400 = Activity 4: $15 × 800 = Total $ 40,000 8,000 12,000 12,000 $ 72,000 Combining Activities 2 and 4 produces a new pooled rate: ($32,000 +$48,000)/400 = $ 200 per setup Overhead assignment: Infantry Activity 1: $2 × 20,000 = $ 40,000 Activity 2*: $200 × 300 = 60,000 Activity 3: $30 × 200 = 6,000 Total $106,000 *Combined activities 2 and 4 Special forces Activity 1: $2 × 20,000 = Activity 2: $200× 100 = Activity 3: $30 × 400 = Total $ 40,000 20,000 12,000 $ 72,000 The assignments are the same and this happens because the consumption ratios of activities 2 and 4 are identical. Thus, rate reduction can occur by combining all activities with identical rates. 3. The two most expensive activities are the first and the combined 2 and 4 activities. Each has $80,000 of cost. Thus if the cost of activity 3 is allocated in proportion to the cost, each of the expensive activities would receive 50% of the $18,000 or $9,000. This yields the following pool rates: Activity (pool 1) 1: ($80,000 + $9,000)/40,000 = $2.225 per machine hour Activities 2 and 4 (pool 2): ($80,000 + $9,000)/400 = $222.50 per setup 87 Overhead assignment: Infantry Pool 1: $2.225 × 20,000 = $ 44,500 Pool 2: $222.50 × 300 = 66,750 Total $111,250 Special forces Pool 1: $2.225 × 20,000 = $ 44,500 Pool 2: $222.5 × 100 = 22,250 Total $ 66,750 4. Infantry: ($111,250 - $106,000)/$106,000 = .05 (rounded) Special forces = ($66,750 - $72,000)/$72,000 = -.07 (rounded) The error is less than 10% for both products. Using machine hours would have produce a rate of $178,000/40,000 = $4.45 per Mhr and an assignment of $89,000 to each product ($4.45 × 20,000). The error for the plantwide rate would be Infantry: ($89,000 - $106,000)/106,000 = 0.16 (rounded) Special forces = ($89,000 - $72,000)/$72,000 = 0.24 (rounded) Thus, the plantwide rate produces product costing errors that are more than three times the magnitude of the approximately relevant ABC assignments. Clearly, the approximation produces a more reasonable and useful outcome and is less complex than the full ABC system. 4–15 1. Unit-level: Testing products, inserting dies 2. Batch-level: Setting up batches, handling wafer lots, purchasing materials, receiving materials 3. Product-level: Developing test programs, making probe cards, engineering design, paying suppliers 4. Facility-level: Providing utilities, providing space 88 PROBLEMS 4–16 1. Cost before addition of duffel bags: $60,000/100,000 = $0.60 per unit The assignment is accurate because all costs belong to one product. 2. Activity-based cost assignment: Stage 1: Activity rate = $120,000/80,000 = $1.50 per transaction Stage 2: Overhead applied: Backpacks: $1.50 × 40,000* = $60,000 Duffel bags: $1.50 × 40,000 = $60,000 *80,000 transactions/2 = 40,000 (number of transactions had doubled) Unit cost: Backpacks: $60,000/100,000 = $0.60 per unit Duffel bags: $60,000/25,000 = $2.40 per unit 3. Product cost assignment: Overhead rates: Patterns: $48,000/10,000 = $4.80 per direct labor hour Finishing: $72,000/20,000 = $3.60 per direct labor hour 89 Unit cost computation: Backpacks Patterns: $4.80 × 0.1 $4.80 × 0.4 Finishing: $3.60 × 0.2 $3.60 × 0.8 Total per unit 4. Duffel Bags $0.48 $1.92 0.72 2.88 $1.20 $4.80 This problem allows us to see what the accounting cost per unit should be by providing the ability to calculate the cost with and without the duffel bags. With this perspective, it becomes easy to see the benefits of the activity-based approach over those of the functional-based approach. The activity-based approach provides the same cost per unit as the single-product setting. The functional-based approach used transactions to allocate accounting costs to each producing department, and this allocation probably reflects quite well the consumption of accounting costs by each producing department. The problem is the second-stage allocation. Direct labor hours do not capture the consumption pattern of the individual products as they pass through the departments. The distortion occurs, not in using transactions to assign accounting costs to departments, but in using direct labor hours to assign these costs to the two products. In a single-product environment, ABC offers no improvement in product-costing accuracy. However, even in a single-product environment, it may be possible to increase the accuracy of cost assignments to other cost objects such as customers. 4–17 1. Plantwide rate = $1,320,000/440,000 = $3.00 per DLH Overhead cost per unit: Model A: $3.00 × 140,000/30,000 = $14.00 Model B: $3.00 × 300,000/300,000 = $3.00 90 2. Calculation of activity rates: Activity Setup Inspection Machining Maintenance Driver Prod. runs Insp. hours Mach. Hours Maint. hours Activity Rate $360,000/100 = $3,600 per run $280,000/2,000 = $140 per hour $320,000/220,000 = $1.454 per hr $360,000/100,000 =$3.60 per hr Overhead assignment: Model A Setups $3,600 × 40 $3,600 × 60 Inspections Model B $ 144,000 $216,000 $140 × 800 112,000 $140 × 1,200 Machining $1.454 × 20,000 $1.454 × 200,000 Maintenance $3.60 × 10,000 $3.60 × 90,000 Total overhead Units produced Overhead per unit 3. 168,000 29,080 290,800 36,000 ----$321,080 ÷ 30,000 324,000 $998,800 ÷300,000 $ $ 10.70 3.33 Departmental rates: Overhead cost per unit: Model A: [($4.66 × 10,000) + ($1.20 × 130,000)]/30,000 = $6.76 Model B: [($4.66 × 170,000) + ($1.20 × 270,000)]/300,000 = $3.72 4. A common justification is that of using machine hours for machineintensive departments and labor hours for labor-intensive departments. Using activity-based costs as the standard, we can say that departmental rates decreased the accuracy of the overhead cost assignment (over 91 the plantwide rate) for both products. Looking at Department 1, this department’s costs are assigned at a 17:1 ratio which overcosts B and undercosts A in a big way. This raises some doubt about the conventional wisdom regarding departmental rates. 4–18 1. Labor and gasoline are driver tracing. Labor (0.75 × $180,000) Gasoline ($4.50 × 6,000 moves) Depreciation Total cost 2. 3. $ 135,000 Time = Resource driver 27,000 Moves = Resource driver 18,000 Direct tracing $180,000 Plantwide rate = $660,000/20,000 = $33 per DLH Unit cost: Basic Prime costs $160.00 Overhead: $33 × 10,000/40,000 8.25 $33 × 10,000/20,000 $168.25 Deluxe $320.00 16.50 $336.50 Activity rates: Maintenance Engineering Material handling Setting up $114,000/4,000 = $28.50 per maint. hour $120,000/6,000 = $20 per eng. hour $180,000/6,000 = $30 per move $ 96,000/80 = $1,200 per move Purchasing $ 60,000/300 = $200 per requisition Receiving Paying suppliers $ 40,000/750 = $53.33 per order $ 30,000/750 = $40 per invoice Providing space $ 20,000/10,000 = $2.00 per machine hour 92 4-18 (continued) Unit cost: Prime costs Overhead: Maintenance $28.50 × 1,000 $28.50 × 3,000 Engineering $20 × 1,500 $20 × 4,500 Material Handling $30 × 1,200 $30 × 4,800 Setting up $1,200 × 16 $1,200 × 64 Purchasing $200 × 100 $200 × 200 Receiving $53.33 × 250 $53.33 × 500 Paying Suppliers $40 × 250 $40 × 500 Providing space $2 × 5,000 $2 × 5,000 Total Units produced Unit cost (ABC) Unit cost (traditional) Basic $6,400,000 Deluxe $6,400,000 28,500 85,500 30,000 90,000 36,000 144,000 19,200 76,800 20,000 40,000 13,333 26,665 10,000 20,000 10,000 $6,567,033 ÷ 40,000 $ 164.18 $ 168.25 10,000 $6,892,965 ÷ 20,000 $ 344.65 $ 336.50 The ABC costs are more accurate (better tracing—closer representation of actual resource consumption). This shows that the basic model was overcosted and the deluxe model undercosted when the plantwide overhead rate was used. 93 4-18 (continued) 4. Consumption ratios: Maint. Eng. Mat. H. Setups Purch. Receiving Pay. Sup Space 5. Basic 0.25 0.25 0.20 0.20 0.33 0.33 0.33 0.50 Delux 0.75 0.75 0.80 0.80 0.67 0.67 0.67 0.50 When products consume activities in the same proportion, the activities with the same proportions can be combined into one pool. This is so because the pooled costs will be assigned in the same proportion as the individual activity costs. Using these consumption ratios as a guide, we create four pools, reducing the number of rates from 8 to 4. Pool 1: Maintenance Engineering Total Maintenance hours Pool rate $114,000 120,000 $234,000 ÷ 4,000 $ 58.50 Note: Engineering hours could also be used as a driver. The activities are grouped together because they have the same consumption ratios: (0.25, 0.75). Pool 2: Material handling Setting up Total Number of moves Pool rate $180,000 96,000 $276,000 ÷ 6,000 $ 46 Note: Material handling and setups have the same consumption ratios: (0.20, 0.80). The number of setups could also be used as the pool driver. 94 4-18 (concluded) Pool 4: Purchasing Receiving Paying suppliers Total Orders processed Pool rate $ 60,000 40,000 30,000 $130,000 ÷ 750 $ 173.33 Note: The three activities are all product-level activities and have the same consumption ratios: (0.33, 0.67) Pool 5: Providing space Machine hours Pool rate $ 20,000 ÷ 10,000 $ 2 Note: This is the only facility-level activity. 4–19 1. Unit-level costs ($120 × 20,000) Batch-level costs ($80,000 × 20) Product-level costs ($80,000 × 10) Facility-level ($20 × 20,000) Total cost $ 2,400,000 1,600,000 800,000 400,000 $ 5,200,000 2. Unit-level costs ($120 × 30,000) Batch-level costs ($80,000 × 20) Product-level costs ($80,000 × 10) Facility-level costs Total cost $ 3,600,000 1,600,000 800,000 400,000 $ 6,400,000 The unit-based costs increase because these costs vary with the number of units produced. Because the batches and engineering orders did not change, the batch-level costs and product-level costs remain the same, behaving as fixed costs with respect to the unit-based driver. The facility-level costs are fixed costs and do not vary with any driver. 3. Unit-level costs ($120 × 30,000) Batch-level costs ($80,000 × 30) Product-level costs ($80,000 × 12) Facility-level costs Total cost $ 3,600,000 2,400,000 960,000 400,000 $ 7,360,000 95 Batch-level costs increase as the number of batches changes, and the costs of engineering support change as the number of orders change. Thus, batches and orders increased, increasing the total cost of the model. 4. Classifying costs by category allows their behavior to be better understood. This, in turn, creates the ability to better manage costs and make decisions. 4–20 1. The total cost of care is $1,950,000 plus a $50,000 share of the cost of supervision [(25/150) × $300,000]. The cost of supervision is computed as follows: Salary of supervisor (direct) Salary of secretary (direct) Capital costs (direct) Assistants (3 × 0.75 × $48,000) Total $ 70,000 22,000 100,000 108,000 $ 300,000 Thus, the cost per patient day is computed as follows: $2,000,000/10,000 = $200 per patient day (The total cost of care divided by patient days.) Notice that every maternity patient—regardless of type—would pay the daily rate of $200. 2. First, the cost of the secondary activity (supervision) must be assigned to the primary activities (various nursing care activities) that consume it (the driver is the number of nurses): Maternity nursing care assignment: (25/150) × $300,000 = $50,000 Thus, the total cost of nursing care is $950,000 + $50,000 = $1,000,000. Next, calculate the activity rates for the two primary activities: Occupancy and feeding: Nursing care: $1,000,000/10,000 = $100 per patient day $1,000,000/50,000 = $20 per nursing hour 96 4–20 Concluded Finally, the cost per patient day type can be computed: Patient Normal Cesarean Complications Daily Rate* $150 225 500 *($100 × 7,000) + ($20 × 17,500)/7,000 ($100 × 2,000) + ($20 × 12,500)/2,000 ($100 × 1,000) + ($20 × 20,000)/1,000 This example illustrates that activity-based costing can produce significant product costing improvements in service organizations that experience product diversity. 3. The Laundry Department cost would increase the total cost of the Maternity Department by $100,000 [(200,000/1,000,000) × $500,000]. This would increase the cost per patient day by $10 ($100,000/10,000). The activity approach would need more detailed information—specifically, the amount of pounds of laundry caused by each patient type. The activity approach will increase the accuracy of the cost assignment if patient types produce a disproportionate share of laundry. For example, if patients with complications produce 40 percent of the pounds with only 10 percent of the patient days, then the $10 charge per day is not a fair assignment. 97 4–21 1. Activity classification: Unit-level: Batch-level: Product-level: Facility-level: 2. Machining Material handling, setups, inspection, and receiving Maintenance and engineering None Pool 1, consumption ratios: (0.5, 0.5): Machining $ 90,000 Activity driver ÷ 100,000 MHr Pool rate $ 0.90 per MHr Pool 2, consumption ratios: (0.75, 0.25): Setups $ 96,000 Inspection 60,000 Total $ 156,000 Activity driver ÷ 80 setups* Pool rate $ 1,950 per setup *Inspection hours could also be used. Pool 3, consumption ratios: (0.33, 0.67): Material handling $ 120,000 Receiving 30,000 Total $ 150,000 Activity driver ÷ 6,000 material moves Pool rate $ 25 per move Pool 4, consumption ratios: (0.67, 0.33): Engineering $ 100,000 Maintenance 80,000 Total $ 180,000 Activity driver ÷ 6,000 maintenance hours* Pool rate $ 30 per maintenance hour *Number of engineering hours could also be used. 98 4–21 3. Concluded Computation of unit overhead costs: Small Clock Unit-level activities: Pool 1: $0.90 × 50,000 $0.90 × 50,000 Large Clock $ 45,000 $ 45,000 Batch-level activities: Pool 2: $1,950 × 60 $1,950 × 20 117,000 Pool 3: $25 × 2,000 $25 × 4,000 50,000 39,000 100,000 Product-level activities: Pool 4: $30 × 4,000 $30 × 2,000 Total overhead costs Units produced Overhead cost per unit 120,000 $ 332,000 ÷ 100,000 $ 3.32 99 60,000 $ 244,000 ÷ 200,000 $ 1.22 4–22 1. Overhead rate = $6,990,000/272,500 = $25.65 per DLH* Overhead assignment: X-12: $25.65 × 250,000/1,000,000 = $6.41* S-15: $25.65 × 22,500/200,000 = $2.89* *Rounded numbers used throughout Unit gross margin: Price Cost Gross margin S-15 $ 12.00 6.02** $ 5.98 X-12 $ 15.93 10.68* $ 5.25 *Prime costs + Overhead = ($4.27 + $6.41) **Prime costs + Overhead = ($3.13 + $2.89) 2. Pools Setup Machine Receiving Engineering Material handling Driver Runs Machine hrs. Orders Engineering hrs. Moves Pool Rate $240,000/300 = $800 per run $1,750,000/185,000 = $9.46/per MHr $2,100,000/1,400 = $1,500/per order $2,000,000/10,000 = $200/per eng. hour $900,000/900 = $1,000/per move 100 4–22 Continued Overhead assignment: S-15 X-12 Setup costs: $800 × 100 $800 × 200 $ $ Machine costs: $9.46 × 125,000 $9.46 × 60,000 567,600 600,000 1,500,000 Engineering costs: $200 × 5,000 $200 × 5,000 Selling price Less unit cost Unit gross margin 160,000 1,182,500 Receiving costs: $1,500 × 400 $1,500 × 1,000 Material-handling costs: $1,000 × 500 $1,000 × 400 Total overhead costs Units produced Overhead cost per kg Prime cost per kg Unit cost 80,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 500,000 $ 3,362,500 ÷ 1,000,000 $ 3.36 4.27 $ 7.63 400,000 $ 3,627,600 ÷ 200,000 $ 18.14 3.13 $ 21.27 $ $ 15.93 7.63 8.30 $ 101 $ 12.00 21.27 (9.27) 4–22 Concluded 3. No. The cost of making X-12 is $7.63, much less than the amount indicated by functional-based costing. The company can compete by lowering its price on the high-volume product. The $10 price offered by competitors is not out of line. The concern about selling below cost is unfounded. 4. The $12 price of compound S-15 is well below its cost of production. This explains why Pearson has no competition and why customers are willing to pay $15, a price that is probably still way below competitors’ quotes. 5. The price of X-12 should be lowered to a competitive level and the price of S-15 increased so that a reasonable return is being earned. 4–23 1. Activity rates: Testing products Purchasing materials Machining Receiving = $252,000/300 = $840 per setup = $36,000/1,800 = $20 per order = $252,000/21,000 = $12 per machine hour = $60,000/2,500 = $24 per receiving hour Overhead cost assignment: Model A Testing products: $840 × 200 $840 × 100 Purchasing materials: $20 × 600 $20 × 1,200 Machining: $12 × 12,000 $12 × 9,000 Receiving: $24 × 750 $24 × 1,750 Total OH assigned Model B $168,000 $ 84,000 12,000 24,000 144,000 108,000 18,000 42,000 $342,000 $258,000 102 2. New cost pools: Testing products: $252,000 + [($252,000/$504,000) × $96,000] = $300,000 Machining: $252,000 + [($252,000/$504,000) × $96,000] = $300,000 New activity rates: Testing products: $300,000/300 = $1,000 per setup Machining: $300,000/21,000 = $14.29 per hour Model A Testing products: $1,000 × 200 $1,000 × 100 Machining: $14.29 × 12,000 $14.29 × 9,000 Total OH assigned Model B $200,000 $100,000 171,480 $371,480 128,610 $228,610 3. Percentage error: Model A: ($371,480 – $342,000)/$342,000 = 0.086 (8.6%) Model B: ($228,610 – $258,000)/$258,000 = –0.114 (11.4%) The error is not bad and is certainly not in the range that is often seen when comparing a plantwide rate assignment with the ABC costs. For example, if Model A is expected to use 30% of the direct labor hours, then it would receive a plantwide assignment of $180,000, producing an error of more than 47%—an error almost six times greater than the approximately relevant assignment. In this type of situation, it may be better to go with two drivers to gain acceptance and get reasonably close to the more accurate ABC cost. It also avoids the data collection costs of the bigger system. 103 4–24 1. Welding Machining Setups Total $2,000,000 1,000,000 400,000 $3,400,000 Percentage of total activity costs = $3,400,000/$4,000,000= 85%. 2. Allocation: ($2,000,000/$3,400,000) × $600,000 = $352,941 ($1,000,000/$3,400,000) × $600,000 = $176,471 ($400,000/$3,400,000) × $600,000 = $70,588 Cost pools: Welding = $2,000,000 + $352,941 = $2,352,941 Machining = $1,000,000 + $176,471 = $1,176,471 Setups = $400,000 + $70,588 = $470,588 Activity rates: Rate 1: Welding = $2,352,941/4,000 = $588 per welding hour Rate 2: Machining = $1,176,471/10,000 = $118 per machine hour Rate 3: Setups = $470,588/100 = $4,706 per batch Overhead assignment: Subassembly A Rate 1: $588 × 1,600 welding hours $588 × 2,400 welding hours Rate 2: $118 × 3,000 machine hours $118 × 7,000 machine hours Rate 3: Subassembly B $ 940,800 $1,411,200 354,000 826,000 104 $4,706 × 45 batches $4,706 × 55 batches Total overhead costs Units produced Overhead per unit 3. 211,770 $1,506,570 ÷ 1,500 $ 1,004 258,830 $2,496,030 ÷ 3,000 $ 832 Percentage error: Error (Subassembly A) = ($1,004 – $1,108)/$1,108 = –0.094 (–9.4%) Error (Subassembly B) = ($832 – $779)/$779 = 0.068 (6.8%) The error is at most 10%. The simplification is simple and easy to implement. Most of the costs (85%) are assigned accurately. Only three rates are used to assign the costs, representing a significant reduction in complexity. 105 MANAGERIAL DECISION CASES 4–25 1. Shipping and warehousing costs are currently assigned using tons of paper produced, a unit-based measure. Many of these costs, however, are not driven by quantity produced. Many products have special handling and shipping requirements involving extra costs. These costs should not be assigned to those products that are shipped directly to customers. 2. The new method proposes assigning the costs of shipping and warehousing separately for the low-volume products. To do so requires three cost assignments: receiving, shipping, and carrying. The cost drivers for each cost are tons processed, items shipped, and tons sold. Pool rate, receiving costs: Receiving cost/Tons processed Pool rate, shipping costs: Shipping cost per shipping item = $1,100,000/56,000 tons = $19.64 per ton processed* = $2,300,000/190,000 = $12.11 per shipping item* Pool rate, carrying cost (an opportunity cost): Carrying cost per year (LLHC) = 25 × $1,665 × 0.16 = $6,660 Carrying cost per ton sold = $6,660/10 = $666 Shipping and warehousing cost per ton sold: Receiving $ 19.64 Shipping ($12.11 × 7) 84.77 Carrying 666.00 Total $770.41 *Rounded 106 4–25 3. Continued Profit analysis: Revised profit per ton (LLHC): Selling price Less manufacturing cost Gross profit Less shipping and warehousing Loss $ 2,400.00 1,665.00 $ 735.00 770.41 $ (35.41) Original profit per ton: Selling price Less manufacturing costs Gross profit Less shipping and warehousing Profit $ 2,400.00 1,665.00 $ 735.00 30.00 $ 705.00 The revised profit, reflecting a more accurate assignment of shipping and warehousing costs, presents a much different picture of LLHC. The product is, in reality, losing money for the company. Its earlier apparent profitability was attributable to a subsidy being received from the high-volume products (by spreading the special shipping and handling costs over all products, using tons produced as the cost driver). The same effect is also true for the other low-volume products. Essentially, the system is understating the handling costs for low-volume products and overstating the cost for high-volume products. 4. The decision to drop some high-volume products and emphasize low-volume products could clearly be erroneous. As LLHC has demonstrated, its apparent profitability is attributable to distorted cost assignments. A significant change in the image of LLHC was achieved by simply improving the accuracy of shipping and handling costs. Further improvements in accuracy in the overhead assignments may cause the view of LLHC to deteriorate even more. Conversely, the profitability of high-volume products may improve significantly with increased costing accuracy. This example underscores the importance of having accurate and reliable accounting information. The accounting system must bear the responsibility of providing reliable information. 107 4–25 5. Concluded Ryan’s strategy changed because his information concerning the individual products changed. Apparently, the accounting system was undercosting the low-volume products and overcosting the high-volume products. Once better information was available, Ryan was able to respond better to competitive conditions. 4–26 1. Disagree. Chuck is expressing an uninformed opinion. He has not spent the effort to find out exactly what activity-based management and costing are attempting to do; therefore, he has no real ability to offer any constructive criticism of the possible benefits of these two approaches. 2. and 3. At first glance, it may seem strange to even ask if Chuck’s behavior is unethical. After all, what is unethical about expressing an opinion, albeit uninformed? While offering uninformed opinions or recommendations may be of little consequence in many settings, a serious issue arises when a person’s expertise is relied upon by others to make decisions or take actions that could be wrong or harmful to themselves or their organizations. This very well may be the case for Chuck’s setting, and his behavior may be labeled professionally unethical. Chuck’s lack of knowledge about activity-based systems is a signal of his failure to maintain his professional competence. Standard I-1 of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice indicates that management accountants have a responsibility to continually develop their knowledge and skills. Failure to do so is unethical. RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT 4–27 Answers will vary. 108