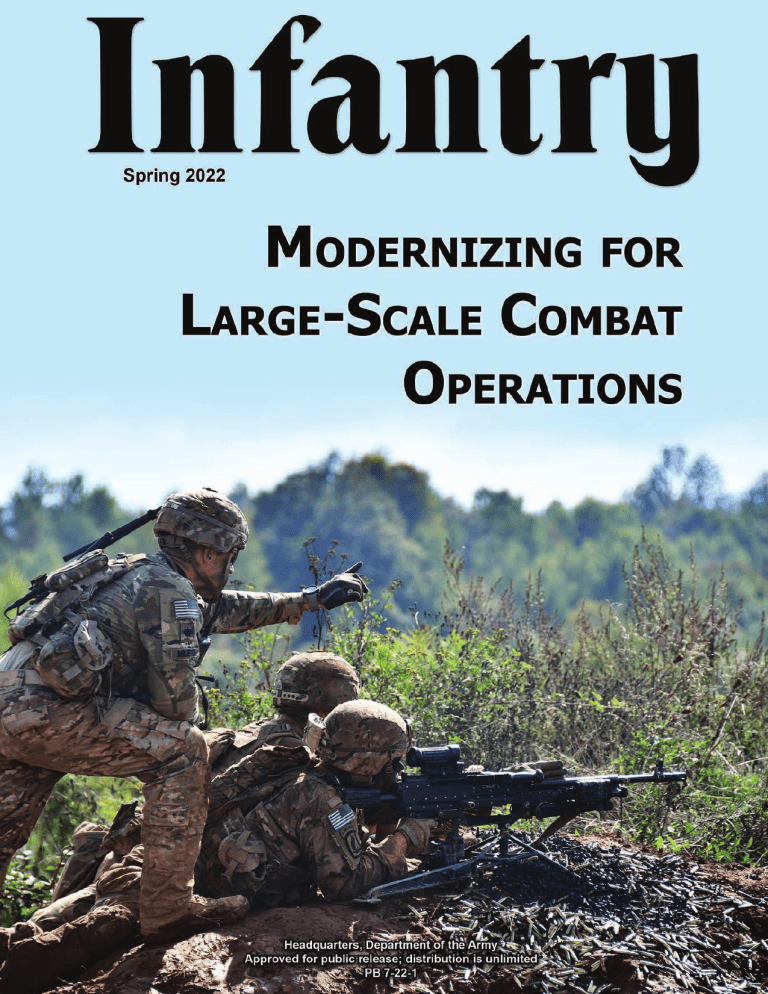

PB 7-22-1 BG LARRY BURRIS Commandant, U.S. Army Infantry School SPRING 2022 RUSSELL A. ENO Editor MICHELLE J. ROWAN Deputy Editor FRONT COVER: The commander of 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment (Airborne), 173rd Airborne Brigade, gives instructions to his Soldiers during live-fire training as part of exercise Eagle Storm in Slunj, Croatia, on 21 September 2021. (Photo by Elena Baladelli) BACK COVER: Soldiers assigned to 3rd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (Airborne), 25th Infantry Division, fire an M3 Multi-role Anti-armor Anti-personnel Weapon System (MAAWS) during live-fire training at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, AK, on 15 September 2021. (Photo by SrA Emily Farnsworth, USAF) This medium is approved for official dissemination of material designed to keep individuals within the Army knowledgeable of current and emerging developments within their areas of expertise for the purpose of enhancing their professional development. By Order of the Secretary of the Army: JAMES C. MCCONVILLE General, United States Army Chief of Staff Official: MARK F. AVERILL Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army 2207700 Distribution: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Volume 111, Number 1 DEPARTMENTS 1 2 COMMANDANT’S NOTE PROFESSIONAL FORUM 2 TRAINING TODAY’S SOLDIERS FOR TOMORROW’S WAR: IMPLEMENTING LSCO INTO OSUT LTC Alphonse J. LeMaire, MAJ Ross C. Pixler, CPT James E. Bryson, CPT Avery W. Littlejohn, CPT Andrew E. Carter, CPT Matthew T. Lunger, CPT Joshua K. O’Neill, and CPT Rory M. Fellows 8 HIGH-ANGLE FIRES AND MANEUVER: RUSSIAN UPGRADED MORTARS MAINTAIN VITAL ROLE ON THE FUTURE BATTLEFIELD Dr. Lester W. Grau and Dr. Charles K. Bartles 16 THE SNIPER’S ROLE IN LARGE-SCALE COMBAT OPERATIONS CPT David M. Wright, SSG Andrew A. Dominguez, and SSG John A. Sisk II 19 INCREASING INDIRECT FIRE CAPABILITY IN THE LIGHT INFANTRY BATTALION CPT Sam P. Wiggins and LTC Alexi D. Franklin 24 SENIOR NCOS AT POINTS OF FRICTION CSM Nema Mobarakzadeh 31 THE INFORMATION DOMAIN AND SOCIAL MEDIA SGM Alexander E. Aguilastratt and SGM Matthew S. Updike 37 ARMY AVIATION — ABOVE THE BEST! NOW LET’S TRAIN TOGETHER CPT Daniel Vorsky 39 USING GOALS TO DEVELOP OUR SUBORDINATES CPT Jacob Mooty 41 THE SFAB: A LIEUTENANT’S EXPERIENCE 1LT Christopher Wilson 44 YOU WILL ACCOMPLISH NOTHING: THE FUNDAMENTAL CHALLENGE FOR SOLDIERS SERVING AS ADVISORS IN SFABS IS UNDERSTANDING SUCCESS MAJ Eric Shockley 47 LESSONS FROM THE PAST 47 DEATH ON THE ROAD TO OSAN: TASK FORCE SMITH CPT Connor McLeod 52 BOOK REVIEWS Infantry (ISSN: 0019-9532) is an Army professional bulletin prepared for quarterly publication by the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning, GA. Although it contains professional information for the Infantryman, the content does not necessarily reflect the official Army position and does not supersede any information presented in other official Army publications. Unless otherwise stated, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense or any element of it. Contact Information Mailing Address: 1 Karker St., McGinnis-Wickam Hall, Suite W-141A, Fort Benning, GA 31905 Telephones: (706) 545-6951 or 545-3643, DSN 835-6951 or 835-3643 Email: usarmy.benning.tradoc.mbx.infantry-magazine@army.mil Commandant’s Note BG LARRY BURRIS Modernizing for Large-Scale Combat Operations O ver the past two decades, the United States has enjoyed technological superiority against adversaries while focusing on counterinsurgency (COIN) warfare in the Middle East. However, during this time, potential threats sought to advance their technological and tactical capabilities to challenge us in the future. The theme of this issue, Modernizing for Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO), is relevant and based on world events — very timely. As this edition of Infantry goes to print, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has entered its fifth week. Sadly, we have seen through ample media coverage the incredible devastation Russia’s military operations have wreaked on Ukraine’s infrastructure and civilian population. This tragedy enables us to study, in real-time, using a likely peer threat, what LSCO may look like in the future. Modernizing for LSCO has several implications for organizing, training, and thinking about future operations. It is impossible to predict with precision what the next fight looks like; however, some factors will likely lead to failure if neglected. The first is that the U.S. Army must always look to improve its ability to conduct operations through a combined arms approach. Applying combined arms begins with the Infantry understanding how other branches operate. In this edition, CPT Daniel Vorsky provides a great article to enhance the Infantry Soldier’s knowledge of working with aviation units. We must also remind ourselves that the high-intensity nature of LSCO requires the effective employment of both direct and indirect fires, kinetic and non-kinetic, to support dismounted Infantry Soldiers. Early observations of the situation in Ukraine show that Russian forces may lack the ability to synchronize fires and maneuver. The U.S. Army must continue advancing our systems, organization, and doctrine to ensure that we do not face similar setbacks in future operations. We must think about the best ways to organize and distribute these critical capabilities within our formations. In this issue, CPT Sam Wiggins and LTC Alexi Franklin provide an excellent starting point for this discussion with their article “Increasing Indirect Fire Capability in the Light Infantry Battalion.” Additionally, we must understand how potential enemies will employ their fires. Readers should pay special attention to the article by Dr. Lester W. Grau and Dr. Charles K. Bartles. They provide a well-timed analysis of how the Russians use their upgraded mortar systems on the battlefield. A third guidepost we can apply is that LSCO will require Soldiers to have a different mindset than COIN. The COIN fight that our Army grew accustomed to over the past two decades prioritized population-based objectives. Engagements with the enemy occurred sporadically and mostly at the platoon level. We must adapt our training so that our Soldiers become familiarized with the environment they will face in high-intensity LSCO. One principle is that LSCO means we will be fighting intense wars of maneuver focused on terrain and threat-based objectives. Such fights will occur at all echelons from the team to division levels while fighting as a joint force. This mindset starts with the “soldierization process” during initial military training. In this edition, officers from 2-58 Infantry Battalion of the 198th Brigade at Fort Benning provide an article discussing how Infantry One Station Unit Training (OSUT) is modernizing for LSCO. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine teaches us that LSCO in the future will be intense, brutal, and demanding. Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates famously said, “When it comes to predicting the nature and location of our next military engagements, since Vietnam, our record has been perfect. We have never once gotten it right.” Of course, Secretary Gates is right — we cannot predict with certainty against who, where, or when the next fight will occur. However, failing to train and employ combined arms, losing our proficiency regarding fire and maneuver, and evading the mindset needed for LSCO will undoubtedly lead to future failures. Ultimately, the Infantry Soldier, whose mission is to close with and destroy the enemy, will pay that price. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 1 Training Today’s Soldiers for Tomorrow’s War: Implementing LSCO into OSUT LTC ALPHONSE J. LEMAIRE, MAJ ROSS C. PIXLER, CPT JAMES E. BRYSON, CPT AVERY W. LITTLEJOHN, CPT ANDREW E. CARTER, CPT MATTHEW T. LUNGER, CPT JOSHUA K. O’NEILL, AND CPT RORY M. FELLOWS “Wars are won by the courage of soldiers, the quality of leaders, and the excellence of training… training that is realistic, meaningful, and thorough… training that convinces our soldiers and our leaders that they can and must win the battle of the next war.” — GEN Donn Starry “The Soldier and Training,” 9 January 19811 T he U.S. Army Infantry School’s (USAIS) One Station Unit Training (OSUT) is designed to transform civilian volunteers into lethal Infantry Soldiers ready to deploy, fight, and win our nation’s wars against any adversary, anytime, and anywhere. This year’s National Security Strategic Guidance highlighted “that the distribution of power across the world is changing, creating new threats,” most notably near-peer adversaries China and Russia.2 To build Infantry Soldiers ready to combat these near-peer threats, the USAIS must implement large-scale combat operations (LSCO)-focused training into its Infantry OSUT program of instruction (POI). The Maneuver Center of Excellence (MCoE) Commanding General MG Patrick Donahoe directed that “our most immediate priority is completing the cognitive disconnect with counterinsurgency (COIN) operations, and ensuring our training focuses on preparing for LSCO.”3 As the lead for the 198th Infantry Brigade, the 2nd Battalion, 58th Infantry Regiment (2-58IN) began optimizing live-fire exercises (LFXs) and situational training exercises (STXs) to install a realistic and challenging experience that certifies trainees on individual Soldier skills through collective infantry tasks while operating in a LSCO environment. This optimization includes educating Infantry trainees on near-peer adversary weapons, equipment, uniforms, and battlefield tactics. Implementing LSCO into Infantry OSUT also capitalizes on the leader development initiative of training leaders at echelon to ensure they are prepared to lead Soldiers to defeat our nation’s enemies in tomorrow’s fight. 2 INFANTRY Spring 2022 Reminiscent of the post-Vietnam Army of 1970s, today’s Army is transitioning from an emphasis on small-scale, COIN-centric conflicts back to LSCO. Over the past two decades, Infantry OSUT focused on small-scale asymmetric threats in a partially contested environment that involved fire team to squad-level dismounted patrols or route clearance missions operating out of forward operating bases or combat outposts. Enemy activity was depicted as capable but technologically and logistically inferior, resulting in Infantry Soldiers developing an overdependence on friendly enablers while maintaining consistent air superiority. This approach produced competent Infantry Soldiers for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, but did so at the expense of preparing to face near-peer competitors. Efforts to transition from COIN to LSCO in Infantry OSUT are well under way in both the LFX and STX training progressions that place a primary focus on performing individual Soldier skills through collective infantry tasks. This article will outline how the application of LSCO-focused training into portions of the 22-week Infantry OSUT cycle will better prepare Infantry Soldiers and leaders to fight our nation’s wars. LSCO in Live-Fire Exercises (LFXs) Infantry OSUT LFX progression consists of Buddy Team LFX (BTT), Fire Team LFX (FTT), and culminates with Enhanced Fire Team LFX (EFLX). It is intended to ground trainees on the individual Soldier skills required to produce lethal Infantry Soldiers ready to combat a near-peer enemy. This progression uses the crawl-walk-run methodology that affords multiple repetitions on the following tasks: - Move as a member of a team; - Engage targets with an M4 Carbine; - Use verbal and non-verbal communication; - Maintain adequate suppressive fire; - Employ hand grenades; - Perform individual movement techniques; and - Select proper cover and concealment to close with and engage an enemy. BTT and FTT are the “crawl” and “walk” that train the fundamentals of operating as a member of a team and reinforce Soldier self-confidence on effectively engaging enemy targets, performing individual movement techniques, and selecting adequate cover and concealment. Building on the foundation established with BTT and FTT, EFLX is the “run” that certifies Soldiers on fundamentals while operating in a more dynamic and challenging environment defined by complex natural terrain without preestablished fighting positions. This challenges Soldiers to accurately select fighting positions while conducting fire and maneuver through natural terrain and is the first LFX where enemy activity influences a fire team’s actions on the objective. While the standards for BTT, FTT, and EFLX remain consistent with doctrine, additions made to implement nearpeer engagements include increasing targets to each lane (simulating engaging a larger force); developing targets that require multiple hits to go down (simulating an enemy with personal protective equipment); and replacing faceless target silhouettes with images of armed foreign soldiers. These refinements remove COIN-centric approaches and instill the challenges of LSCO. Creating Near-Peer Opposition Forces (OPFOR) “The United States Army faces an inflection point... Our Nation’s adversaries have gained on [U.S. Army] qualitative and quantitative advantages. If the Army does not change, it risks losing deterrence and preservation of the Nation’s most sacred interests.” — GEN James C. McConville, Army Chief of Staff4 To optimize the LSCO training environment, Infantry OSUT needed to change the way it portrays a known OPFOR. Infantry Soldiers must become familiar with and train against an OPFOR that accurately represents a near-peer adversary who can engage forces across a range of military operations like Russia, China, Iran, or North Korea. Over the past two decades, Infantry OSUT OPFOR typically consisted of trainees operating in small, three-to-four-person teams armed with M4s, wearing Army Combat Uniforms, and executing tactics to match the incompetence of a small insurgent force. While that provided an easily controlled method for drill sergeants to prepare Soldiers for the Global War on Terrorism fight, it willfully missed on a variety of opportunities to enhance the fundamentals of fire and maneuver that produce versatile Infantry Soldiers. The 2-58IN is validating a method towards improving OPFOR for a LSCO environment by incorporating foreign uniforms, weapons, tactics, and an organizational structure that replicates a near-peer enemy. Coordination with the Training Aid Service Center helped establish an “OPFOR Package” consisting of foreign military uniforms, flags, insignia, and weapons such as AK-47s, rocketpropelled grenades (RPGs), PKMs (Pulemyot Kalashnikovas), AK-74s, RPKs (Ruchnoy Pulemyot Kalashnikovas), and SVDs (sniper rifles). This package includes modification equipment from the Army National Guard Exportable Combat Training Center that enables U.S. Army high mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles (HMMWVs) to resemble Russian BRDMs. These OPFOR adjustments improve collective training lanes by exposing actual enemy uniforms, weapons, and equipment. Units can resource this Photos courtesy of 2nd Battalion, 58th Infantry Regiment package to augment and provide A Soldier in training with 2-58IN engages enemy targets from a selected fighting position in natural terrain during the Enhanced Fire Team Live-Fire Exercise. realism to any situational trainSpring 2022 INFANTRY 3 PROFESSIONAL FORUM At left, an OPFOR soldier engages Bravo Company, 2-58IN during a squad attack collective training lane. Above, OPFOR soldiers prepare for a near ambush against a friendly infantry squad during a field training exercise. ing exercise. Additionally, 2-58IN resourced visual threat noise-light-litter discipline, and Soldier field craft; posters that display weapons and equipment capabilities - Shifting from a non-contiguous/non-linear battlefield of Russian, Chinese, Iranian, and North Korean militaries. setting to a contiguous linear battlefield setting with particuBoards for each country are hung in platoon bays through- lar respect to conducting defensive operations; and out company training areas that enable Soldiers to regularly - Introducing a disciplined OPFOR that wears enemy identify, study, and understand the capabilities and tactics uniforms, uses enemy weapon systems, and fights with of potential enemies. These applications provide a LSCO enemy tactics to accurately reflect combating our anticipated focus that improves the development of Infantry Soldiers near-peer adversaries. and their understanding of our The Forge is the first STX where Foreign Military Threat Boards potential adversaries. trainees conduct individual Soldier LSCO in Situational Training Exercises (STX) The Infantry OSUT STX progression begins with the Forge exercise that certifies trainees to become Soldiers and is followed by squad tactical training (STT) and the field training exercise (FTX)/Bayonet that certifies Soldiers to become Infantry Soldiers. After a thorough review of the STX progression, it became apparent that adjustments were necessary to instill a focus on LSCO. These adjustments include: - Increasing physical rigor and mental hardship on Soldiers while operating as a member of a team; - Enforcing strict standards towards individual camouflage, 4 INFANTRY Spring 2022 skills through collective Infantry tasks. The key LSCO-focused training events are: - Formations and Order of March (FOOM), - Night Infiltration Course (NIC), - Battle March and Shoot, and - Patrol Base Operations. FOOM is the introduction to squad and platoon-level movement and maneuver that includes advancing through restrictive terrain under both day and night conditions; this is the event where trainees increase familiarization on operating with night vision devices. The NIC simulates maneuvering while under direct enemy fire during hours of limited visibility, like what is anticipated in LSCO. Battle March and Shoot incorporates strenuous physical and mental challenges before transitioning into a “stress shoot.” The purpose is to put trainees under duress before performing a live-fire engagement wearing a full combat load. Additionally, this event also presents a chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) live-fire engagement that simulates engaging enemy targets in a contaminated environment. Throughout the Forge, trainees conduct patrol base operations that include how to occupy, establish security, construct fighting positions, and perform priorities of work consisting of weapons maintenance and field hygiene while enforcing noise-light-litter discipline. These events inculcate the necessary individual Soldier skills for LSCO as well as build the foundation to progress into STT and the FTX/Bayonet where Soldiers will be contested by an OPFOR. STT builds upon the foundations established during Forge through an emphasis on squad collective training. STT mirrors the FTX/Bayonet and is where Soldiers gain an understanding of squad battle drills, establish squad and platoon fighting positions, and execute collective training lanes against a designated OPFOR. STT institutes a LSCO focus with companies occupying an assigned training area in a defensive posture oriented against a near-peer enemy threat. This company defensive posture reinforces individual and introduces squad and platoon-level fighting positions that serve as a launch point for squad collective training against an OPFOR. During this four-day STX, Soldiers get multiple repetitions performing the collective tasks required to advance into the FTX/Bayonet. The Infantry OSUT FTX/Bayonet are the culminating events that certify and produce Infantry Soldiers. During these two events, Soldiers execute squad and platoon collective training against an internally resourced OPFOR operating with a specific mission and intent that mimic a near-peer enemy. The FTX begins with the company establishing an area defense with mutually supporting platoon fighting positions. This generates a linear area of operations against an enemy force that is likely in a LSCO fight. Companies then transition into shaping operations consisting of the following platoon and squad collective training lanes: squad attack; movement to contact; near and far ambush; anti-armor ambush; react to contact/ambush; knock out a bunker; enter/clear a trench; and platoon attack. These collective training lanes reinforce the individual and collective tasks taught during Forge and STT with an additional emphasis on Soldier leadership. Collective training lanes during shaping operations are led by platoon leaders and platoon sergeants, with Soldiers rotating as squad leaders and fire team leaders while drill sergeants serve as observer-coach-trainers. A typical FTX collective training lane consists of a squad receiving a mission while in its assigned defensive position. The squad then executes a series of assigned tasks Soldiers in 2-58IN defend against an OPFOR attack during the FTX. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 5 PROFESSIONAL FORUM on this opportunity, 2-58IN instituted a tactical orders process into the FTX/Bayonet event. The orders process trains a fundamental skill required of leaders at multiple echelons and is essential for preparing junior officers and NCOs to lead Soldiers in future LSCO. The 2-58IN Battalion Staff presents a large-scale combat operations Company cadre prior to their cycle’s FTX/Bayonet event. against a designated OPFOR that simulates a near-peer enemy. At the completion of each training iteration, the squad returns to its established defensive position while remaining under constant enemy surveillance. This serves as the mechanism for achieving a continuously contested environment that includes periodic enemy probes into defensive positions, reaction to indirect fires and air attacks, and the occasional CBRN attack to simulate a contaminated battlefield. The FTX shaping operations phase consists of five days of continuous activity before transitioning into the Bayonet. The Bayonet is the final 48 hours of the FTX that consists of a 12-mile tactical foot movement followed by a platoon raid on a designated enemy objective occupied by OPFOR. Once Soldiers successfully complete the FTX/ Bayonet, they are ready to advance to become “Infantry Soldiers.” Incorporating LSCO into STX progression better prepares Infantry Soldiers to integrate into any operational unit across the Army ready to quickly develop into a fire team leader. The use of a LSCO tactical operation order (OPORD) in a company’s FTX/Bayonet enables battalion commanders to develop leaders at echelon beginning with the battalion staff and continuing through company command teams, platoon leaders/platoon sergeants, and drill sergeant cadre. For each company’s FTX/Bayonet, this process begins with the battalion issuing a tactical OPORD that provides the overall “road to war” (from division to company) and delivers the company’s mission and intent for its assigned training area of operations. After receiving the battalorder to Charlie ion OPORD, company commanders produce a company OPORD issuing specified tasks for the shaping operations phase of the FTX. The shaping operations phase is the period where company command teams rotate platoons and squads through collective training lanes against an OPFOR in a continually contested environment. Throughout this phase company command teams assess platoon leaders and platoon sergeants on their ability to create and brief fragmentary orders (FRAGOs), as well as how drill sergeants evaluate assigned Soldiers on the individual Soldier skills required for graduation. Shaping operations occur over a five-day period before transitioning into the FTX’s final 48 hours, or Bayonet event. Roughly 48 hours prior to transitioning into the Bayonet, companies receive a FRAGO from battalion directing a platoon raid on a designated enemy objective. This FRAGO provides an additional repetition of the orders process for battalion, company, and platoon-level leadership and Leader Development “Leader development is our top priority. It is through the touchpoints we have with junior maneuver officers and NCOs that we are capable of changing the trajectory of the Army... we must capitalize on every opportunity to make leaders who are more prepared to lead Soldiers in today’s Army, and in future large-scale combat operations.” — MG Patrick Donahoe5 The effort to implement LSCO into Infantry OSUT reveals additional ways to accomplish one of the MCOE commander’s top priorities of leader development. Leader development is defined as “the deliberate, continuous, sequential, and progressive process… that grows leaders capable of decisive action.”6 To capitalize 6 INFANTRY Spring 2022 A platoon leader briefs the Bayonet mission fragmentary order to his platoon. presents an updated enemy situation and mission for the final 12-mile foot movement and platoon collective training lane. The battalion commander, command sergeant major, executive officer, operations officer, and operations sergeant major observe, coach, and mentor cadre on their performance of each company and platoon OPORD brief as well as the execution of the Bayonet event. Feedback is given to junior officers and NCOs following each iteration to facilitate leader development. Implementing the orders process into the FTX/ Bayonet undoubtedly strengthens junior officers and NCOs to integrate into any operational unit prepared to fight and win in future LSCO. Summary This article outlines enhancements to Infantry OSUT that are improving the development of Infantry Soldiers through applications that simulate LSCO. The 2-58IN made deliberate adjustments to install a LSCO focus with no changes to the current POI by critically analyzing LFX and STX training, OPFOR creation and utilization, and leader development opportunities. This includes increasing the number of targets for lane iterations, developing targets that require multiple hits to go down, and replacing faceless target silhouettes with images of armed foreign soldiers into the LFX progression. With STX progression, 2-58IN improved educating cadre and Soldiers on potential adversaries’ military weaponry and its capabilities, and implemented a realistic OPFOR that looks, acts, and fights like a near-peer enemy operating in a continually contested environment on a linear battlefield. Finally, 2-58IN incorporated the orders process for the FTX/ Bayonet that places a deliberate focus on the training and development of junior officers and NCOs towards LSCO. The cost associated to resource these applications and training adjustments are nearly negligible both in time and money. However, the payoff is real, tangible, and directly impacts the readiness of training today’s Infantry Soldiers for tomorrow’s war. Notes 1 Lewis Sorley, Press On! (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute, 2009), 717. 2 The White House, “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” Whitehouse.gov, last modified 3 March 2021, accessed from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/ 2021/03/03/interim-national-security-strategicguidance/. 3 MG Patrick Donahoe, “Fiscal Year 2022 Annual Mission Guidance,” Fort Benning, GA: Maneuver Center of Excellence, 2021, 3. 4 GEN James C. McConville, “Army Multi-Domain Transformation: Ready to Win in Competition and Conflict,” Headquarters, Department of the Army, 16 March 2021, i. 5 Ibid, 2. 6 Army Regulation 600-100, Army Profession and Leadership Policy, 2017, 32. LTC Alphonse J. LeMaire currently commands 2-58IN, 198th Infantry Brigade, Fort Benning, GA. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and master’s degrees from Kansas State University, Air University, and the School of Advanced Military Studies. He is also a graduate of the Air Command and Staff College. LTC LeMaire has served in various command and staff positions that include the Army Talent Management Task Force, 25th Infantry Division, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), and the 4th Infantry Division. He has completed multiple tours in both Iraq and Afghanistan. MAJ Ross C. Pixler currently serves as the executive officer (XO) of 2-58IN. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the U.S. Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, NY; a master of art degree from Colombia University; and a master of art and science degree from the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, KS. He has served in various command and staff positions that include the 3rd Infantry Division, 10th Mountain Division, 101st Airborne Division (AASLT), and West Point instructor and tactical officer. He has served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. CPT James E. Bryson currently serves as the operations officer for 2-58IN. His previous assignments include serving as a Stryker platoon leader in A Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry Battalion; weapons platoon senior observer-coach-trainer (OCT) with Task Force 2; division battle captain in Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion; and commander of Charlie Company, 2-54IN. CPT Bryson earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from Arizona State University and a master’s degree in business administration from Grand Canyon University. CPT Avery W. Littlejohn commanded Alpha Company, 2-58IN. His previous assignments include serving as a platoon leader with 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Benning, and with 4th Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, Fort Carson, CO. CPT Littlejohn earned a bachelor’s degree in systems engineering from USMA. CPT Andrew E. Carter currently commands Bravo Company, 2-58IN. He previously served as a platoon leader in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment in Vilseck, Germany. CPT Carter earned a bachelor’s degree in technical management from Northern Arizona University. CPT Matthew T. Lunger currently commands Charlie Company, 2-58IN. He is a former enlisted Infantry Soldier who spent three years in 1st Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, Fort Richardson, AK, which included a 12-month deployment to Afghanistan in 2009-2010. He then served five years as a team member through section leader in a dismounted reconnaissance company in 3rd Squadron, 61st Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, and included additional Afghanistan deployments in 2012 and 2014. After commissioning, CPT Lunger served as an assistant S3 and rifle platoon leader in 2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, 173rd Airborne Brigade, in Vicenza, Italy; and as company XO in Delta Company, 2-58IN. He earned a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and public policy from the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs. CPT Joshua K. O’Neill currently commands Delta Company, 2-58IN. His previous assignments include serving as a rifle platoon leader and mortar platoon leader in 4th Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment, 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division, Fort Bliss, TX. He earned a bachelor’s degree in defense and strategic studies from USMA. CPT Rory M. Fellows currently serves with the 1st Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, Fort Hood, TX. He previously commanded Echo Company, 2-58IN. His other assignments include serving as a platoon leader in Bandit Troop, 1st Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment, which deployed to Afghanistan from April 2016 to February 2017. He earned a bachelor’s degree in military history from Norwich University in Northfield, VT. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 7 PROFESSIONAL FORUM High-Angle Fires and Maneuver: Russian Upgraded Mortars Maintain Vital Role on Future Battlefield DR. LESTER W. GRAU DR. CHARLES K. BARTLES A rtillery has been integrated into Russian Army infantry regiment tables of organization and equipment (TO&Es) since at least Peter the Great (1682-1725). His 1707 field regulations specified that two three-pounder cannon or two mortars be standard in every infantry regiment. Guard’s regiments would have more.1 Cannon artillery and/or mortars have been organic to Russian maneuver units for centuries. These were separate from the standard artillery battalions assigned to the infantry regiments or operational reserves. The cannon crews and mortar crews organic to infantry battalions have always been manned by artillerymen. During World War II, Soviet infantry battalions had two Model 1937 45mm semiautomatic wheeled anti-tank guns and six 82mm mortars. Since World War II, the composition and size of the organic artillery in infantry battalions have varied. The 1949 Soviet rifle battalion had an artillery battery of two wheeled Model 1948 57mm anti-tank guns, four 12.7mm heavy machine guns, and four PTRD-41 anti-tank rifles as well as a mortar battery of nine 82mm mortars.2 Concepts began to change in the Soviet Army with the death of Stalin in 1951. Future war was expected to be fought exclusively with atomic weapons, and maneuver units were reduced in size to become less attractive targets. The Soviet motorized rifle battalion experienced at least seven more significant TO&E changes before the collapse of the Soviet Union. Cannon artillery and recoilless rifles disappeared while anti-tank guided missiles entered the force. For a brief period, when the Soviets determined that future war would only be atomic, mortars disappeared. But with the realization that future war could be nuclear or conventional maneuver war under nuclear-threatened conditions, mortars came back and have remained. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian armed forces underwent a sweeping reform with the ground forces built primarily around brigades and combined arms armies rather than regiments, divisions, and armies. They retained BMP-equipped and BTR-equipped motorized rifle battalions. Each of these battalions includes an eight-mortar battery of either 120mm 2S12 “Sani,” 82mm 2B14 “Podnos,” or 82mm 2B9 Vasilek mortars.3 Except for the brief period during preparations solely for an atomic battlefield, Soviet and Russian ground forces have always wanted organic battalion-level “hip-pocket” 8 INFANTRY Spring 2022 artillery available to decimate the enemy before, during, and after contact. The mortar is that weapon of choice for enemy equipment and personnel. The anti-tank guided missile and anti-tank grenade launcher are the weapons of choice for enemy tanks. The locale of war is changing from set-piece contests in open-maneuver spaces to mountains, deserts, thick forests, marshland, and urban areas — areas that negate many of the advantages of newer technology. Mortars and light anti-tank weapons are ideal for these locales as they are transportable, effective, and relatively easy to emplace. Western forces and Russian forces view tactical war differently. The West thinks that artillery supports maneuver and that the best way to kill a tank is with another tank. Russian forces think that artillery enables maneuver and the best way to kill a tank is with an anti-tank weapon. The true value of Russian tanks is proven when they are committed deep inside the enemy rear area seizing or destroying key infrastructure and support facilities. Despite these conflicting views, neither side would disagree that the correlation between the range of fire systems and the reach of maneuver elements is now changing because the range of artillery is increasing while the speed of advance of maneuver formations is not.4 The Not-So-Humble Mortar The 120mm 2B11 Sani [Сани-sled] has been in the inventory since 1981. It won a state design prize in 1984. This 4.7-inch mortar remains in Russian motorized rifle battalion batteries but is being replaced by the upgraded 2S12A Sanicomplex.5 The emplaced weapon weighs 230 kilograms (507 pounds) and it is moved on a 2x1 wheeled chassis (designated 2L81). The mortar construction is rigid and does not have a recoil-absorption system. The new baseplate has an internal rotating firing plate which allows 360-degree engagement without time-consuming repositioning of the base plate or removal of the smooth-bore barrel. It includes a device to prevent double loading and provides a rate of fire of up to 15 rounds per minute. Night-firing holds no special challenges, and the improved gunsight can be rapidly adjusted.6 The “Sani’s” main function remains motorized rifle direct support. Afghanistan combat proved that mortars are irreplaceable in mountainous and rugged terrain and in wooded areas where artillery fire is ineffective.7 In the city fighting Maximum firing range – 7,100 meters (up to 9,000 meters using the “Gran” precision fire system) Minimum firing range – 480 meters Maximum rate of fire – up to 15 rounds a minute (damage) on it in which it completely loses its combat capability. The probability of hitting individual targets is 0.7-0.9 or the mathematical expectation that 50-60 percent of targets within a group will be hit. Annihilation of a target renders it unusable. Maximum initial speed of mortar round – 325 meters a second Portable munitions load – 56 rounds Mortar weight in combat configuration – 230 kilograms Mortar weight with 2L81 wheeled carriage – 357 kilograms Crew – 5 men Table 1 — 2S12 Sani Specifications 8 in Grozny, Chechnya, mortar fire caused the bulk of the casualties.9 In addition to the normal high-explosive (HE) fragmentation, smoke, illumination, incendiary, and leaflet rounds, 2S12A mortars also use the KM-8 “Gran” guidedprojectile system, an HE fragmentation round with the 9E430 laser-guided self-homing seeker and the “Malakhit” automated fire control system (or the laser range finder beam). The “Gran” enables first-round hits without firing for adjustment against mobile and fixed targets at day or night. If multiple targets are located within 300 meters of each other, a single firing angle is sufficient and the gunsight does not need to be adjusted. Tests of the “Gran” system demonstrate its accuracy where six of every eight rounds will hit right on target.10 Mobility and rapid displacement are important to mortar survivability. The 2S12A “Sani” mortar is transported on a Ural-43206-0651 all-wheel drive truck or towed behind it. The 2F32 special equipment package (electric winch, loading planks, and bracing material) is carried in the truck bed. This equipment enables the crew to move the mortar from the traveling position into a firing position (and back) in under three minutes. The old 2B11 mortar required 20 minutes. A MT-LB lightly armored tractor can also be used as the prime mover.11 Suppression of the target inflicts such losses on it that it temporarily loses its combat capability, restricts its maneuver, or disrupts control. The number of targets hit is about 30 percent. Harassment is the moral and psychological impact on the enemy from firing a limited number of mortar and artillery rounds for a specified time.13 Types of fire planning for a mortar battery: When engaging an enemy with fire, artillery subunits use the following fire planning: fire against an individual target, fire concentration, standing barrage fire, deep standing barrage, moving barrage, successive fire concentrations, offensive rolling barrage, and massed fire.14 Fire against an individual target is battery, platoon, or individual mortar fire conducted independently from a covered firing position. Figure 1 — Fire Against an Individual Target, in this case, an Enemy Anti-tank Guided Missile Fire concentration is fire conducted simultaneously by several batteries on one target. The mortar battery fires a concentration area as part of a higher-level artillery plan. The maximum area for the mortar battery within a fire concentration is eight hectares. The ability to shoot and quickly vacate the firing position is essential to crew survival. Russia has fielded turreted mobile 82mm and 120mm gun-mortars which include breechloading, rifled tubes that can fire HE, white phosphorus, and smoke. These are mounted on tracked and wheeled chassis. Some motorized rifle battalion mortar batteries use these hybrid gun-mortars instead of the Sani. They are more mobile but have a lower rate of fire.12 Mortar Fire Planning When a target is designated (depending on its nature, importance, and the combat situation), the firing missions of artillery subunits can be: destruction, annihilation, suppression, or harassment. Destruction of the target consists of inflicting such losses Figure 2 — Fire Concentration Standing barrage fire is a continuous curtain of fire created in front of an attacking (or a counterattacking) enemy. It is used to repel attacks (counterattacks) of enemy infantry. The width of the fixed barrage fire sectors are assigned at Spring 2022 INFANTRY 9 PROFESSIONAL FORUM vehicles. The distance between the lines of the mobile barrage fire, depending on enemy speed, can be 400-600 meters. The width of the mobile barrage fire battery sector is assigned at the rate of no more than 25 meters per mortar. Barrage fires are assigned the names of predatory animals, such as “Lion,” “Tiger,” etc., and each line, starting from the most distant one, has its own designated number. A moving barrage is often planned in conjunction with a howitzer battalion. Sometimes the first two lines are fired simultaneously as in a deep standing barrage. Figure 3 — Standing Barrage Fire the rate of no more than 50 meters per mortar. The boundaries of fixed barrage fire sectors are assigned tree names such as “Beech,” “Birch,” etc. The mission is fired with HE fragmentation mortars. When conducting a single fixed barrage fire, firing begins at the moment the infantry and tanks approach the fixed barrage fire line of fire and continues until the infantry is cut off from the tanks and the attack (counterattack) is stopped. If the enemy’s infantry takes cover, the firing transitions to a fire concentration mission. A deep standing barrage is a continuous curtain of fire on the axis of enemy tank and infantry fighting vehicles which are fired simultaneously on several lines of fire. The lines may be 400-600 meters apart, and the width of the lines are not more than 25 meters per mortar. Successive fire concentrations are used for fire support of an attack. Successive fire concentration lines are assigned after determining the formation of the enemy’s defense at 300-1,000 meters from one another. The borders of the successive concentrations of fire are assigned names of predatory animals, such as “Lion,” “Tiger,” etc., which are numbered in the order of priority of their firing at them, starting from the closest line. The mortar battery will normally participate with an individual concentration as part of a larger battalion or brigade artillery group successive fire concentrations plan. When planning the lines of the successive fire concentrations, the mortar battery target concentration is assigned on the first line, the area of which should not exceed two hectares. Figure 4 — Deep Standing Barrage A moving barrage is a continuous curtain of fire created at one line on the axis of enemy tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and armored personnel carriers and sequentially transferred to other designated lines as the main mass of the enemy leaves the zone of fire. A moving barrage is prepared at several lines located on the path of movement of enemy Figure 5 — Moving Barrage 10 INFANTRY Spring 2022 Figure 6 — Successive Fire Concentrations An offensive rolling barrage is used for fire support of an attack. It is conducted along the main and intermediate lines. The main lines of the offensive rolling barrage fire are assigned every 300-1,000 meters from one another, and the intermediate ones are assigned 100-300 meters between the main lines. The main lines of the barrage fire are assigned names of predatory animals, such as “Fox,” “Tiger,” etc., while the lines are numbered in the order of priority of firing them, starting from the closest line. Intermediate lines are numbered separately from the main ones and are named 1st intermediate, 2nd intermediate, etc. The mortar battery will normally participate with an individual concentration as part of a larger battalion or brigade artillery group successive fire trated or within an area, as well as some dug-in unarmored vehicles positions, as a rule, are destroyed. The targets of artillery (mortar) fire are usually enemy platoon strongpoints, mortar platoons, command and observation posts, radar stations, and companies in assembly areas and on the march. The firing capabilities of artillery to engage enemy targets with fire from covered firing positions are determined by the nature of the targets and engagement, number of available mortars, quantity and quality of available ammunition, and required time to complete tasks.15 Depending on the number of mortars at the disposal of the battalion (company), the duration of fire, and the mode of fire, the number of required mortars can be determined. Divide this number by the average ammunition consumption rate to obtain the number of objects that can be suppressed (destroyed) during the artillery preparation of the attack. Mortar Battery on the Offensive Figure 7 — Offensive Rolling Barrage concentrations plan. The size of the mortar battery concentration is determined at the rate of 15 meters per mortar. Massed fire is conducted simultaneously by all or most of the artillery against an enemy grouping with the goal of decisively hitting one or several important targets in a short time. The mortar battery may have a fire concentration within the massed fire or be part of a howitzer battalion concentration. As a rule, fixed targets that are unobservable from the mortars but seen from Figure 8 — Massed Fire forward observers — such as unprotected unarmored targets — are destroyed, and covered and armored targets are suppressed or destroyed. The entire battery, and often higher artillery, is used against such targets. Enemy artillery, mortar batteries and platoons, as well as individual guns, are struck in their firing positions. Batteries (platoons) of self-propelled guns are rapidly fired upon, as a rule, immediately upon their detection. Uncovered deployed personnel and weapons are usually suppressed. Enemy anti-tank weapons (anti-tank missiles and anti-tank guns), depending on the situation, are destroyed or suppressed. Groups of unarmored and lightly armored vehicles in concen- In the offense, the mortar battery destroys or suppresses the enemy’s means of nuclear and chemical attacks, artillery and mortar batteries, tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, antitank and other direct fire weapons, personnel, command posts, communications, and fortifications. In order to carry out these fire missions, the mortar battery is deployed into its combat formation. The combat formation consists of the mortar platoons deployed into their firing positions, a command and observation post, and, if necessary, an observation post (forward and lateral). The mortars are located in covered firing positions with intervals of 20-40 meters between them. The mortar transport vehicles are placed behind the mortars, to the right or left of them in a covered position at a distance of 300-500 meters.16 The command post is intended for the observation of the enemy and terrain, controlling fire and maneuvering units, observing the actions of the troops, and maintaining interaction with them. The command post of the battery is collocated with the command post of the motorized rifle battalion or designated motorized rifle company. In order to deploy the Table 2 — Mortar Battery Maximum Fire Coverage by Area and Line17 Artillery Assigned Quantity 120mm Mortar 8 Artillery Support of the Attack Concentrated Successive Fire Concentration of Fire 8 hectares 2 hectares 20 acres 5 acres Barrage Fire Barrage Fire Fixed Barrage Fire Moving Barrage Fire 120 meters 400 meters 200 meters 131 yards 437 yards 219 yards Table 3 — Mortar Battery Assets18 System Quantity of Mortars Rounds per Mortar Total Rounds Platoons Command Posts Radar 120mm Mortar 8 54 432 2 1 1 Spring 2022 INFANTRY 11 PROFESSIONAL FORUM mortar battery in combat formation, the firing positions and the command post site are designated. The firing positions of the mortar battery are 1-1.5 kilometers from the front-line positions of friendly troops. When attacking a defending enemy from the march, the battery, if it is involved in the preparation of the attack, must take up its firing position no later than 1.5-2 hours before the start of the artillery preparation of the attack. Deployment in combat formation is carried out, as a rule, at night, hidden from enemy ground and air observation. This time is needed to prepare the mortars for firing, lay out the ammunition (which will be used during the artillery preparation of the attack) on the ground, ensure spacing between mortars, and aim the mortars at the targets on which fire will first be laid.19 Artillery fire engagement in an offensive is carried out by phases: artillery support for the advance of troops, artillery preparation for the attack, artillery support of the attack, and artillery support for troops advancing in depth. Success in this phase of fire support, distinctly designed for this attack, determines the achievement of the artillery in the subsequent phases.20 Artillery preparation for the attack begins at a set time and, as a rule, with the approach of a motorized rifle company to the line of deployment in battalion columns. At this time, the mortar battery, at the signal of the senior commander, begins its missions. Artillery preparation for the attack begins with sudden heavy fire strike by all artillery on planned targets, and above all on personnel and means of fire on the front line, artillery batteries, and other important targets. Artillery preparation ends at the appointed time with a fire strike on the strong points of the first echelon companies and anti-tank weapons. Covering fire is carried out against artillery and mortar batteries. It usually begins before the end of the artillery preparation and ends with the arrival of motorized rifle subunits on the front edge of the enemy’s defense, coinciding with the attack time on the front line.21 Artillery support for the attack begins when the motorized rifle companies reach the line of transition to the attack and continues until the motorized rifle subunits capture the first echelon areas of a brigade (regiment). The transition to artillery support is carried out without any interruption in firing. Artillery support can be carried out by various methods — single or double successive fire concentrations, fire barrages, concentrated fire, fire against a single target, and combinations thereof. There may be other methods as well. An expedient method of fire support is one that provides a greater degree of simultaneous destruction of direct fire weapons, especially anti-tank guided missiles, at the greatest distance possible. Calls for fire and shift fire, in addition to the command to start fire support for the attack, may be given by the battalion commander.22 Fire accompaniment of troops in the depth is carried out as the offensive develops throughout the depth of the enemy defense. It begins after the end of artillery support for the attack 12 INFANTRY Spring 2022 and continues until the motorized rifle subunits complete their combat missions. During artillery accompaniment, the mortar battery can perform the following tasks: ensure the entry into battle of the second echelons, repulse counterattacks by the enemy reserve, support subunits when crossing water obstacles, and pursue retreating enemies. During this period, the mortars, as a rule, perform on-call fire missions. The battery can conduct fire against an individual target, fire concentration, standing barrage fire, and massed fire.23 The preparation of a mortar battery for an offensive begins with receiving a mission from the battalion commander. After receiving the mission from the battalion commander at the set time, the battery commander is obliged to support the company commander, for whose support the battery is assigned or supporting, and report the composition, position, condition, and security of the battery; the missions received and the established ammunition consumption; the battery’s fire capabilities; the assigned areas for firing positions and location of the command post; the time and order of their occupation; the order of movement during the battle; and the required time needed to open fire. He must be ready to answer the company commander’s questions regarding the use of the battery in battle.24 In order to support the motorized rifle battalion (company) commander, the battery commander arrives at the indicated place to conduct reconnaissance and receive the mission and coordinating instructions. When providing the combat missions for the mortar battery, the battalion commander indicates the following in the combat order: the targets for destruction and/or suppression during the period of fire preparation of the attack, with the time of the start of the attack and whom to support, the tasks of ensuring the entry into battle of the second echelon and repelling enemy counterattacks, firing positions, route and order of advance, time of readiness to open fire, and order of movement during the battle.25 At the set time and at the signal (command) of the senior commander, the battery opens fire and performs tasks according to the artillery support plan. The battery commander controls the execution of his subordinate platoons’ fire missions and monitors the results of the fires, correcting them if necessary. At the beginning of the attack, the battery suppresses and/or destroys the planned and newly identified enemy targets. As tank and motorized rifle subunits approach the line of fire, the mortar battery commander, at the direction of the motorized rifle battalion (company) commander, transfers fires to the next line in the sequence to ensure a safe distance from the exploding mortars for friendly troops. When new targets are discovered, the battalion commander sets tasks for their suppression and/or destruction.26 The movement of the mortar battery is carried out by order of the battalion commander. It begins after the companies of the first echelon have taken possession of enemy platoon strongpoints on the front line of the enemy’s defenses. Depending on the nature of the actions of the enemy and friendly subunits, the battery can move as a whole battery or by individual platoons. The battery commander is obliged to move the command post in a timely manner and maintain contact with the battalion (company) commander. The second echelon of the battalion is brought into action under artillery cover. The battery suppresses the enemy’s firepower, as a rule, with a heavy fire lasting 8-10 minutes. During this time, enemy direct and indirect firepower should diminish as the second echelon moves to the line of engagement. During the offense, subunits must be constantly prepared to repel enemy counterattacks. Upon detection of advancing enemy reserves, the battery commander adjusts the firing line, taking into account the change in the direction of the enemy’s counterattacks. Artillery repels a counterattack by enemy tanks and infantry with moving barrage fire and standing barrage fire. When the enemy retreats, the mortar battery often moves and deploys in combat formation. Firing positions are usually located near roads.27 Mortar Battery in the Defense In the defense, mortar batteries usually occupy positions away from tank avenues of approach, prominent local features, and on low ground.28 The mortar firing position can be dug by hand, but the major excavation is usually done by the brigade’s engineer battalion equipment. The battery in the defense carries out fire engagement of the enemy in cooperation with other means of destruction and the following tasks: - Using artillery for interdicting and attacking the deployment areas of enemy troops; - Using artillery to repulse an enemy attack; - Conducting artillery support of troops defending in depth; and - Using artillery to defeat the enemy during friendly counterattacks.29 In order to perform firing missions in the defense, the battery selects at least two firing positions so it can maneuver during the battle. The nearest avenues of approach to the firing positions are mined. The main firing positions of a mortar battery are usually assigned within the battalion defensive area, behind the companies of the first echelon. Figure 9 — Fighting Position for the 2S12 Sani Mortar30 Reserve firing positions are selected on the flanks of the main area and in the depths of the defense. Command observation and observation posts of artillery (mortar) subunits are usually deployed within the battalion defensive area in order to create a system of continuous observation of the enemy in front of the forward edge of the line of defense, and to ensure survivability, they are scattered along the front and in depth. In order to defeat the enemy effectively in the defense, an artillery fire system will be created, which consists of the advance preparation of concentrated and defensive fires to defeat the enemy on the avenues of approach to the defense, in front of the forward edge of the front line and in depth, as well as the concentration of fire on any threatened axis.31 A battery’s fire capabilities will determine its ability to perform tasks in defense. The preparation of a battery for combat in defense depends on the conditions for the transition to defense, the mission received, the nature of the enemy, and available time. During the transition to the defense in conditions of direct contact with the enemy, the battery commander, in accordance with the decision of the battalion commander, sets the task of preparing the fire for capturing and securing the specified line, providing flanks and gaps, and repelling possible attacks by the enemy. Subsequently, all the necessary measures are taken to prepare for the defense. When organizing the defense when not in contact with the enemy, the battery commander receives missions, as a rule, from the battalion commander during reconnaissance. Regardless of the conditions for the transition to defense, the battery commander participates in the reconnaissance and coordination activities, contacts the company commander to whom he is assigned and reports the following: the composition, position, condition, and security of the battery; tasks received from the battalion commander; the locations of the firing positions; ammunition status; fire capabilities; and location of the command post. The battalion commander coordinates the actions of the companies and batteries to defeat the enemy in the course of refining the plan of battle and also clarifies the methods of target designation, warning signals, control, and coordination. After the reconnaissance, the battalion commander will issue a combat order, including assigning artillery tasks.32 During the advance and deployment of the enemy, the battery lays fire concentrations and fire against individual targets, attempting to inflict defeat on the advancing enemy. When the enemy transitions to the attack, the battery conducts standing barrage fire or moving barrage fire on the combat formations of the advancing enemy subunits. During this time, the artillery fires with the greatest intensity. The battery uses barrage fire to defeat tanks and other armored vehicles, to disrupt the combat formations of enemy units, and to cut off the infantry from the tanks. Calls for fire are directed by the commanders of the company and battalion. In the event of a penetration of the enemy into the defensive area of the battery, the battery lays fire concentrations, Spring 2022 INFANTRY 13 PROFESSIONAL FORUM Mission Ammunition Expended Basic Load/Rounds Potential Enemy Suppression Artillery denies 0.3 enemy advance and 26x8=208 deployment Fire concentration on mechanized infantry platoon in two columns – 120 rounds;1-2 separate targets – 90 rounds Artillery defeats enemy attacks 0.5 40x8=320 Moving barrage fire – 2-3 lines – 160 rounds: 2nd Moving Barrage Fire – 110 rounds; 1 target – 50 rounds Artillery supports defending units in depth 0.5 40x8=320 Fire concentrations – 2 mech infantry platoons in combat formation – 110 rounds; Standing Barrage Fire – 3 sites – 160 rounds; 1 target – 50 rounds Fire destruction of enemy counterattack 0.4 32x8=256 Fire concentrations – 2 mech infantry platoons in combat formation – 110 rounds; 1 mortar platoon – 110 rounds; 1 target – 40 rounds Figure 10 — Conceptual drawing of Russian 82mm automatic robot-mortar35 maneuver for the Russian ground combat units. Notes 1 O. Leonov and I. Yl’yanov, Регулярная Пехота: Боевая Летопись, Организация, Table 4 — Mortar Rounds Expended for Defense Fire Missions33 Обмундирования, вооружение, Снаружение 1698-1801 [Regular Infantry: Military Annals, standing barrage fire, or moving barrage fire in an attempt Organization, Uniforms, Armaments, Supply 1698-1801], Moscow: to prevent the spread of the enemy into the depth of the TLO “ACT”, 1995, 24-25. 2 Lester W. Grau, “The Soviet Combined Arms Battalion — defense and towards the flanks. Reorganization for Tactical Flexibility,” Soviet Army Studies Office, When the friendly second echelon conducts a coun- 1989, 3, accessed from https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA216368. terattack, the battery can be assigned to support it. pdf. There are also brigades mounted on tracked MTLB armored When the command post moves to a new location, the carriers operating in boggy, marshy or Arctic areas that are orgabattery commander establishes contact with the battalion nized like BTR-equipped brigades. 3 Lester W. Grau and Charles K. Bartles, The Russian Way of War: commander. The battery supports the battalion by laying fire Force Structure, Tactics, and Modernization of the Russian Ground concentrations and fire against individual targets. Priority Forces, Foreign Military Studies Office, 2016, 211, accessed from firing targets are enemy artillery and mortar batteries, anti- https://community.apan.org/wg/tradoc-g2/fmso/p/fmso-bookshelf. tank weapons, tanks, personnel, and direct-fire weapons 4 Jack Watling, “The Future of Fires: Maximising the UK’s that must be suppressed in the direction of the friendly Tactical and Operational Firepower,” RUSI Occasional Paper, Royal counterattack. United Service Institute for Defence and Security Studies, London, November 2019, 18. Other consequences of the increase in range Conclusion are the ability of a smaller number of guns to bring a higher proportion Mortars or gun-mortars will remain a vital part of the of the groups fire to bear in support of a specific maneuver brigade Russian motorized rifle battalion. They provide responsive, and the extent of the “last-mile resupply” of ammunition, food, and increasingly accurate fire support and masking particulate- fuel5 is extended over 50 kilometers behind the FLOT, 19. Petyr Nikolaev, “You Don’t Joke with the Sanis. The Reliable smoke cover to the maneuver force. However, as unmanned Mortar Acquires a ‘Second Breath’ and Remains a Serious Threat to aerial vehicles and high-precision fires become common on the Enemy,” Armeyskiy Standart [Army Standard], https://armystanthe battlefield, mortar crew mortality should rise. Further, dard.ru/, 26 April 2021. 6 combat in the Arctic and Far North is difficult for mortar crews Ibid. 7 in the open for extended periods of time. The Russians are Ibid. 8 Ibid. field testing the 82mm automatic mortar mounted on a small 9 N. N. Novichkov, V. Ya. Snegovskiy, A. G. Sokolov and V. Yu. Kamaz truck chassis (the Drok) [Gorse] and the 120mm gun howitzer mounted on a large truck chassis (the 2S40 Shvarev, Rossiyskie vooruzhennye sily b chechenskoim konflikte: Floks [Phlox]) or the Magnolia articulated tracked Arctic analiz, itogi, vyvody [Russian armed forces in the Chechen conflict: analysis, results and outcomes], Moscow: Holweg-Infoglobe-Trivola, vehicle. Russians engineers are investigating the develop1995, 131. ment of 82mm robot-mortars which will operate separately 10 Nikolaev. 11 from the firing crew.34 These efforts — combined with the Ibid. 12 improvements in the mobility, accuracy, and rate of fire of Murat Rafikhovich Toekin, Минометная Батарея в Основных artillery battalions and brigades — should continue to enable Видах Боя [The Mortar Battery in the Basic Types of Combat], 14 INFANTRY Spring 2022 Almaty: Kazakhstan University, 2002, 6. 13 Ibid. 14 Fire planning section derived from Toekin, 6-9, and Grau and Bartles, 243-250. 15 Toekin. 16 Ibid, 12. 17 Ibid, 10. 18 Ibid. 19 Ibid. 20 Ibid, 12-13. 21 Ibid, 13. 22 Ibid. 23 Ibid, 13-14. 24 Ibid, 14. 25 Ibid, 15. 26 Ibid. 27 Ibid, 16. 28 With the introduction of the “Gran” precision firing system, high elevation positioning of part of the battery may be ideal when using laser-beam target identification. 29 Toekin, 17. 30 Ground Forces Combat Regulations: Part 2 Battalion and Company [Боевой устав сухопутных войск: часть 2 батальон рота], Moscow: Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, 2014. 31 Toekin, 17. 32 Ibid, 17-18. 33 Ibid, 18. 34 D. Pervykhin, G. Mitrofanov, V. Del’ros and I. Kruglov, Совершенстование Артиллерии: Внедрение научнотехнических решений--залог успешного выполнения огневных задач артеллерии [Perfecting artillery: Inculcating scientific-technical decisions — securing the successful accomplishment of artillery fire missions], Армеиский Сборник [Army Digest], February 2021, 63-71. 35 Ibid, 71. Dr. Les W. Grau, a retired Infantry lieutenant colonel, is research director for the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, KS. His previous positions include serving as senior analyst and research coordinator, FMSO; deputy director, Center for Army Tactics, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth; political and economic adviser, Allied Forces Central Europe, Brunssum, the Netherlands; U.S. Embassy, Moscow, Soviet Union; battalion executive officer, 2nd Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, Republic of Korea and Fort Riley, KS; commander, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Support Brigade, Mannheim, Germany; and district senior adviser, Advisory Team 80, Republic of Vietnam. His military schooling includes U.S. Air Force War College, U.S. Army Russian Institute, Defense Language Institute (Russian), U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Infantry Officer Advanced Course, and Infantry Officer Basic Course. He has a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Texas-El Paso, a master’s degree in international relations from Kent State University, and a doctorate in Russian and Central Asian military history from the University of Kansas. His awards and honors include U.S. Central Command Visiting Fellow; professor, Academy for the Problems of Security, Defense and Law Enforcement, Moscow; academician, International Informatization Academy, Moscow; Legion of Merit; Bronze Star; Purple Heart; and Combat Infantryman Badge. He is the author of 13 books on Afghanistan and the Soviet Union and more than 250 articles for professional journals. Dr. Grau’s best-known books are The Bear Went Over the Mountain: Soviet Combat Tactics in Afghanistan and The Other Side of the Mountain: Mujahideen Tactics in the Soviet-Afghan War. Dr. Chuck Bartles is an analyst and Russian linguist with FMSO at Fort Leavenworth. His specific research areas include Russian and Central Asian military force structure, modernization, tactics, officer and enlisted professional development, and security-assistance programs. Dr. Bartles is also a space operations officer and lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserve who has deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq and has also served as a security assistance officer at embassies in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan. He has a bachelor’s degree in Russian from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, a master’s degree in Russian and Eastern European Studies from the University of Kansas, and a PhD from the University of Missouri-Kansas City. From the Foreign Military Studies Office Bookshelf Russian Military Art and Advanced Weaponry by Timothy Thomas Russian General Staff Chief Valery Gerasimov has continually requested that the Academy of Military Science provide him with ideas about new forms and methods of warfare. One source defined “methods” as the use of weaponry and military art. Weaponry is now advanced and is characterized by new speeds, ranges, and agilities, which introduce new ways for Russian commanders to apply force. Military art takes into consideration advanced weaponry’s contributions to conflict along with a combination of both old and new combat experiences, the creativity and innovative capabilities of commanders, and new ways for considering or adding to the principles of military art (mass, surprise, etc.). https://community.apan.org/wg/tradoc-g2/fmso/m/fmso-books/352075/download The Russian Way of War: Force Structure, Tactics, and Modernization of the Russian Ground Forces by Dr. Lester W. Grau and Charles K. Bartles Russia’s 2014 annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, activity in Eastern Ukraine, saber rattling regarding the Baltics, deployment to Syria, and more assertive behavior along its borders have piqued interest in the Russian armed forces. This increased interest has caused much speculation about their structure, capabilities, and future development. Interestingly, this speculation has created many different, and often contradictory, narratives about these issues. At any given time, assessments of the Russian armed forces vary between the idea of an incompetent and corrupt conscript army manning decrepit Soviet equipment and relying solely on brute force, to the idea of an elite military filled with special operations forces who were the “polite people” or “little green men” seen on the streets in Crimea. This book will attempt to split the difference between these radically different ideas by shedding some light on what exactly the Russian ground forces consist of, how they are structured, how they fight, and how they are modernizing. https://community.apan.org/wg/tradoc-g2/fmso/m/fmso-books/199251/download Spring 2022 INFANTRY 15 PROFESSIONAL FORUM The Sniper’s Role in LargeScale Combat Operations CPT DAVID M. WRIGHT SSG ANDREW A. DOMINGUEZ SSG JOHN A. SISK II T raditionally, the sniper in U.S. Army doctrine and training has been an underutilized and misunderstood asset available to the tactical level commander. Snipers are specially trained in long-range marksmanship and infiltration. Their use and effectiveness by special operations forces during the Global War on Terrorism have brought a heightened level of awareness and attention to the sniper in American culture. Simultaneously to this increase in notoriety, the U.S. Army has moved in the opposite direction by focusing on high-end fires and maneuver capabilities. These changes are necessary to ensure the Army is ready for a fight against a near-peer or peer adversary in the multi-domain environment. When commanders employ snipers effectively, they create an advantage during large-scale combat operations. Over the last 15 years, our adversaries have observed our success in ground combat at the tactical level. They have focused on developing capabilities that limit the Army’s ability to maneuver and make decisions. America’s military is viewed as over-reliant on technology, joint fires capabilities, and unmanned systems that provide information for kinetic effects. Our opponents aim to deny information through anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) and target fixed American formations with fires delivered from outside our effective range.1 This approach leaves a gap for commanders to empower aggressive and intelligent subordinates to operate without leveraging American technological capabilities. When the Army is not massed and needs to establish a foothold, the sniper can expose vulnerabilities and give context to unmanned aircraft system footage and collected imagery. “As the Army and the joint force focused on counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism at the expense of other capabilities, our adversaries watched, learned, adapted, modernized and devised strategies that put us at a position of relative disadvantage in places where we may be required to fight.” — LTG Michael D. Lundy Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations Soldiers assigned to the 2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 7th Infantry Division conduct sniper training alongside members of the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force as part of exercise Rising Thunder at Yakima Training Center, WA, on 10 December 2021. Photo by Sgt. Ayato Takei, Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force 16 INFANTRY Spring 2022 We expect our adversaries to employ a mixture of conventional tactics, terror, criminal activity, and information warfare to complicate the battlefield and limit options. This environment will require commanders to become more comfortable assuming risk to develop a situation. It also requires a commander to exploit all assets available to provide a clear picture of the battlefield. Commanders require information to generate options and make decisions. The Department of Defense has invested billions into giving that information. There is a perception that the sniper has no place in this environment. The sniper section augments the overwatch and reconnaissance capabilities of the scout platoon at the battalion level. Gaining and maintaining contact without the enemy being aware retains freedom of maneuver for the commander. In armored and Stryker brigade Photo by SSG Cody Forster combat teams, snipers should move with the mounted scout sections to maintain pace and Snipers from 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry Regiment, 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, conduct training in Alaska. infiltrate their assigned positions. Leaving the sniper team as an overwatch asset also allows the scout that can disrupt the enemy’s defensive planning and engageplatoon to continue answering battalion priority intelligence ment area development. Snipers provide a unique capability requirements for terrain or defining the enemy disposition to disrupt, fix, and isolate small formations through precision and composition in greater detail. A commander can effec- or indirect assets. Precision fires create casualties, lower tively decide the place and time to converge maneuver morale, and affect the enemy’s decision-making process.3 assets against the enemy’s most vulnerable point with a Employing snipers in the offense requires commanders to clearer picture of the battlefield.2 accept risk. Detailed and coordinated planning between the battalion staff and the sniper section helps mitigate and Enabling Tasks reduce risk. During large-scale combat operations, brigade combat In the Defense teams seize ground and hold it. Utilizing snipers during these phases generates options for a commander. The sniper The U.S. Army conducts the defense to shape favorable team leader is trained and experienced in processing infor- conditions for returning to offensive operations. Snipers mation according to the commander’s guidance and helps continue to offer options for the commander to disrupt, develop those options. Institutionally trained snipers learn delay, and fix formations in the defense. Snipers are experts to infiltrate and remain undetected, making them the best at infiltration, making them very useful in identifying enemy option to observe an enemy operating in its defensive plan. avenues of approach not easily seen from defensive posiThe sniper can identify breach points in buildings and routes tions. Using snipers as forward observers allows commandto and from support-by-fire positions in any terrain. They ers to disrupt the enemy’s plan and force an early deployment confirm information with high-powered optics or unmanned into their offensive plan. Snipers are experts at target detecaircraft systems. If needed, the sniper team provides a preci- tion and vehicle identification. They provide the commander sion fire capability that a commander can employ against the means to orient on the enemy without betraying friendly identified weapon emplacements as well as high-payoff and defensive positions. Snipers can provide the location and high-value targets. In addition, a sniper team can neutral- disposition of the enemy’s breaching equipment, fire support ize vehicles, equipment, and enemy leadership. It can also platforms, and assault force from a concealed position. provide additional isolation to prevent enemy maneuver. Snipers can delay and fix formations using direct fires from These capabilities augment the commander’s plan with a long range when unobserved. Fixing an element at the edge low cost to combat power and precision capabilities, maxi- of the engagement area allows commanders to leverage their most casualty-producing weapons against the enemy mizing the economy of force for a given task. for a more extended period. On the Offense A sniper can force the enemy to orient combat power away from the friendly main effort focusing on an objectively small shaping effort. Snipers give the commander an asset The Sniper’s Future Commanders may hesitate to employ snipers due to a lack of experience operating with them in a decisive action Spring 2022 INFANTRY 17 training environment for various reasons. Commanders need to invest in their snipers and train sniper employment to combat this. The Soldiers’ time is misused when they practice prone shooting on a static range. Sniper teams and sections should train on infiltration against skilled observers, mounted and dismounted land navigation, battle handover rehearsals, and pattern of life recognition. These skills are critical to meeting the commander’s intent in the field. With force modernization on the horizon, the U.S. Army Sniper Course cadre and supporting communities have gone to great lengths to prepare for tomorrow’s conflicts. The sniper will engage multiple types of threats with a single weapon platform. The MK22 Precision Sniper Rifle will allow snipers to choose the proper system and type of munition to engage soft or hard targets. The sniper can effectively engage targets up to 2,000 meters reliably when used with the Improved Night/Day Observation Device (INOD). These additions to the inventory allow the U.S. Army sniper to continue owning the night while increasing distances to ensure overmatch and lethal effects. The art of tactics is having a creative and flexible array of means to accomplish the mission against an adaptive enemy. Snipers have proven themselves a reliable asset throughout America’s campaigns and should be considered so for future conflicts. Leaders with questions on sniper employment capabilities should start with their sniper section leader and sniper team leaders on capabilities and limitations. 18 INFANTRY Spring 2022 A student attending the U.S. Army Sniper Course trains on infiltration techniques in June 2020. Photo by Patrick A. Albright Training Circular (TC) 3-20.40, Training and Qualification – Individual Weapons, provides the current ammunition and qualification strategy for snipers. Commanders should also include sniper teams and sections in company certification live fires and situational training to develop trust between commanders and the sniper teams that support them. TC 3-22.10, Sniper, provides the doctrine for sniper training and employment considerations. The cadre at the United States Sniper Course continues to update doctrine and develop new strategies to increase proficiency for sniper teams at home stations. For information regarding the United States Army Sniper Course, head to https://www.benning.army.mil/ Armor/316thCav/Sniper/. Notes Field Manual 3-0, Operations. Center for Army Lessons Learned (CALL) Handbook 10-01, Commander’s Guide to Snipers, October 2009. 3 Army Techniques Publication 3-21.20, Infantry Battalion. 1 2 CPT David M. Wright currently serves as commander of C Company, 1st Battalion, 29th Infantry Regiment, at Fort Benning, GA. SSG Andrew A. Dominguez currently serves as an instructor with C Company, 1-29 IN. SSG John A. Sisk II currently serves as an instructor with C Company, 1-29 IN. Increasing Indirect Fire Capability in the Light Infantry Battalion CPT SAM P. WIGGINS LTC ALEXI D. FRANKLIN “[…] you’re going to have to rapidly aggregate to achieve mass and combat power to achieve an effect on a battlefield. So it’s going to have to be a force that’s essentially in a stage of constant motion.” D — GEN Mark A. Milley1 uring the Cold War, the division was the Army’s unit of action, with division field artillery (DIVARTY) formations organizationally centralized and oriented against a peer or near-peer threat in large-scale combat operations (LSCO). During the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), field artillery assets were assigned directly to the brigade combat team (BCT), and division-level fires synchronization withered. Post GWOT, the Army is reorganizing in order to deter or defeat our enemies during LSCO, and the division is returning as the Army’s unit of action. However, while divisional synchronization may be the U.S. Army’s goal for the way it wants to fight in the future, the most likely and most dangerous course of action is that the enemy will attempt to deny the U.S. Army that ability to conduct a division-level combined arms fight. While the U.S. Army may want to fight LSCO with divisions as the primary unit of action, the enemy gets a vote. While the U.S. Army is correct to prepare to synchronize at the division level, we must also be prepared to fight at the lowest possible level when the command and control (C2) systems we rely on to achieve synchronization are inevitably attacked. However, the Field Artillery Branch cannot simply swing the pendulum back to a pre-GWOT operational construct. If the division is the unit of action, the natural response of our enemies will be to target our ability to effectively exercise divisional mission command. During the pre-GWOT era, our opponents had limited means to disrupt our communications either through the limitations of the electromagnetic spectrum or a robust U.S. overmatch. That reality no longer exists. The U.S. is vastly more reliant on digital C2 systems, and our competitors possess robust C2 denial systems — anti-satellite weapons and advanced cyber and electronic warfare tools — that they have already employed (or have given to their proxies to employ) in battle. As a result, while the Army prepares to synchronize fires at above the brigade level, it must also prepare to devolve its fires assets below the brigade level. In the future, the operational environment in which light infantry formations might find themselves — megacities, triple canopy jungles — will likely be combined with the ability of peer and near-peer competitors to severely degrade the U.S. Army’s capability to centrally control indirect fires in support of dispersed elements. Desynchronization is one cyberattack or severe weather incident away. The Army needs to pre-position fires in space, doctrine, and task organization to be prepared to fight decentralized at a moment’s notice while those assets remain prepared to support centralized objectives. Habitually organized and trained decentralized fires can enable desynchronized maneuver elements to still accomplish their tactical objectives nearly uninterrupted following a desynchronizing event. The current operational approach is a one-size-fits-all approach where the infantry brigade combat team (IBCT), armored brigade combat team (ABCT), and Stryker brigade combat team (SBCT) deconflict air and ground assets to focus indirect fire efforts on the deep fight. The current Soldiers in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment fire a M777A2 howitzer during a live-fire exercise in Germany on 19 October 2021. Photo by Markus Rauchenberger Spring 2022 INFANTRY 19 PROFESSIONAL FORUM approach centralizes the preponderance of our tactical indirect fire assets into a few C2 nodes, with primary communication occurring through only a few, relatively severable communications pathways. While fast-moving ABCTs and SBCTs will be both targeting and the target of high-value enemy targets residing in the enemy’s support zone, the light infantry brigade and battalion will move at a significantly slower pace, leveraging their skills to clear and hold severely restricted terrain. Mounted maneuver formations have inherent levels of mobility, survivability, and firepower to mitigate intermittent C2 disruption, but the light infantry does not. While devolving assets to all types of BCTs is advisable, at a minimum, the light infantry needs closer control of field artillery assets in order to be able to effectively fight in a degraded C2 environment. If also provided sufficient small unmanned aerial system (SUAS) assets, the light infantry battalion can revolutionize the way it fights and more effectively closes with and destroys the enemy. As currently written, field artillery doctrine discusses the current near-peer threat in general terms but lacks the conceptual follow-through to mitigate that clearly articulated threat. Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 3-19, Fires, acknowledges that “[p]eer threats will attempt to isolate friendly forces in all domains and the information environment to force friendly forces to culminate prior to accomplishing their mission,” but the tone and tenor of Field Manual (FM) 3-09, Fire Support and Field Artillery Operations, does not seem to operationalize this concept. Per FM 3-09, one of the characteristics of fire support is “to always operate as a single entity,” a mandate at odds with the conclusion that opponents will seek friendly isolation. The manual further describes field artillery support as a “top-down process with bottom-up refinement,” a principle again at odds with the potential for isolation. The majority of the explicit considerations in Annex C, Denied, Degraded, and Disrupted Operations, of FM 3-09 are focused on solving highly technical, cannon-centric solutions — how observers should be prepared to locate targets with a map and compass or how to survey a firing location with limited technical aids. In Annex C’s short “threat to network connectivity” section, the manual suggests that “[i]f digital communication are denied or degraded [...] data can be transmitted by voice. If voice communications are not possible, courier or liaison personnel can be utilized.” This is an impractical solution not reasonably executed by a light infantry battalion that is both geographically and organizationally remote from artillery support. In lieu of field artillery support operating as a single entity managed from the top down, the paradigm needs to be reversed: light infantry field artillery support needs to be designed on the premise that fighting isolated is not a possibility but an inevitability. Field artillery assets can and should be leveraged for centrally managed operations at higher levels but must be devolved to the lowest possible levels to enable physically and electromagnetically isolated battalions to maintain the initiative in a denied, degraded, and disrupted environment. Simply put, a habitually attached 20 INFANTRY Spring 2022 fires capability could not as easily be cut off from its parent infantry battalion headquarters in a desynchronizing event. The direct procedural relationship and physical proximity between a field artillery unit and maneuver forces at the lowest possible level would allow for near-uninterrupted operations even in a degraded communications environment. Provided greater indirect fire synchronization and execution capability, the isolated maneuver formation can retain the initiative in the offense or maintain or transition to a strong defensive posture by developing engagement areas with field artillery coverage. With our near-peers’ numerically superior long-range cannons and rockets, their doctrine for their employment, and their willingness to use them with fewer concerns for collateral damage, centralized friendly C2 structures are at an increased risk for destruction. Currently, calls for fire are ideally sent digitally from an observer to the battalionlevel fire support element and relayed again to the brigade (or higher) for deconfliction; then they are sent to the firing battalion for execution. This cumbersome process slows the tempo of units and serves as a single communications thread for the enemy to attack. Friendly centralized indirect fire command and control nodes represent no-fail, singularly critical channels through which fire support must travel. In the last 20 years of combat, light infantry forces were commonly the main effort and became accustomed to general access to close air support on a nearly on-call basis. In LSCO against peer competitors, the United States will not enjoy air supremacy and will more likely than not operate under a condition of air parity or denial. Our peer competitors have advanced integrated anti-aircraft systems and robust, modern air forces. In the air, air assets will be dedicated to achieving air superiority and conducting attacks against high-value and payoff targets in the enemy’s support zone. On the ground, armored and Stryker forces will serve as friendly main effort forces while light infantry is relegated to a secondary role, to follow-on to clear secured or bypassed urban or austere terrain. Within the IBCT itself, an increased indirect fire capability at the battalion level would free up IBCT-level fires to shape the brigade commander’s deep fight where large, massed fires are needed. Providing additional organic artillery to the IBCT’s four maneuver battalions (three infantry battalions and one cavalry squadron) complicates the enemy’s targeting by quadrupling the number of nodes the enemy must sever in order to deny the ability of U.S. forces to conduct combined arms warfare. This is not to imply that devolved field artillery formations would only or even mostly operate in a disaggregated fashion; a functioning higher-echelon headquarters could still direct disaggregated batteries to prioritize fires and synchronize effects elsewhere — the reverse is not true. It is a significantly more complex — if not impossible — challenge for a field artillery battalion to, in the heat of battle, unexpectedly and immediately transition, disaggregate, and fight in an ad hoc way should its higher headquarters be unable to direct its efforts. A light infantry battalion should have a semi-organic, habitually affiliated fires battery, similar to a forward support company’s (FSC) command and support relationship between a maneuver and support battalion. Adding a field artillery battery directly subordinate to the infantry battalion will increase the maneuver commander’s ability to rapidly employ indirect fires to effectively shape engagements in the near-peer or peer fight. Closer control over indirect fire assets would allow a battalion-level commander to increase the tempo of combat operations with a rapidity of violence, disrupting the enemy’s decision-making cycle. A hypothetical light infantry fires battery could consist of the battalion’s organic mortar platoon, currently associated fire support section, and a third field artillery platoon with a key capability — three high mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicle (HMMWV)-mounted 105mm tube artillery “Hawkeye” platforms, a weapons system currently undergoing Army evaluation and testing. When compared to a towed M119, the superior maneuverability of the Hawkeye and its smaller gun crew allows the system to penetrate severely restricted terrain with a reduced footprint. As HMMWVs are already organic to an infantry battalion, the increased sustainment requirements for the light infantry battalion’s FSC will be modest in both parts and manpower. Currently, the light infantry battalion’s mortar platoon operates both 81mm and 120mm systems in an “arms room” concept, where the platoon is not allocated the manpower to operate both systems simultaneously. For mission planning, battalion commanders are forced to either choose one system — thus negating the advantage of having two systems with significantly different advantages and disadvantages — or bring both systems and the appropriate ammunition. In garrison, the battalion’s mortar platoon is forced to crew, train, and maintain proficiency on two systems, an additional training burden that can result in expertise on neither system. Replacing the trailer-mounted 120mm mortar with a battalion-level fielding of the Hawkeye system can solve all these problems. The Hawkeye system can ably fill the role that the light infantry battalion’s 120mm systems fill but with its own dedicated manning, longer range, additional ammunition types, a smaller crew, and a reduction in towed rolling stock. The Hawkeye’s mobility and ability to emplace and displace rapidly make it much better suited for evading counterbattery fire. Given the near-peer capability and capacity for effective counterbattery fire, speed will serve to increase the survivability of the Hawkeye platforms which, in turn, helps keep the light infantry formations combat effective. The Hawkeye can fire almost twice as far as the 120mm mortar system and can also be effectively employed in a direct-fire role. Ideally, the battery would be commanded by a major, providing the battalion commander with a seasoned field artillery officer to coordinate execution and delivery of effects. While in a garrison or conducting training, the battery commander would function as a traditional battery commander with regard to training and administrative oversight. In tactical and operational environments, the battery commander would transition to his secondary role to become the battalion’s fire support coordinator (FSCORD). The battalion fires support officer would retain primary focus on the planning and implementation of fire support, with the battery commander/FSCORD focusing on mortar and howitzer displacement and emplacement, engagement criteria, sustainment, and communications. The establishment of the battalion’s FSCORD to a position equal to the battalion’s S3 and executive officer would provide the expertise and staffing to help synchronize the paramount importance that fires planning has on the survival of a light infantry battalion in LSCO. A Soldier with Test Platoon, 2nd Battalion, 122nd Field Artillery, Illinois Army National Guard, sights in the Hawkeye 105mm Mobile Weapon System during a simulated drill on Camp Grayling, MI, on 23 July 2019. Photo by MAJ W. Chris Clyne Spring Spring 2022 2022 INFANTRY INFANTRY 21 21 PROFESSIONAL FORUM major war that then followed was heavily influenced by the capability of the belligerents to integrate and implement the lessons learned from the previous, smaller conflict. The employment of SUAS to great effect in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war should serve as a cautionary tale to the paucity of employment and integration of SUAS in the U.S. Army today. One of the mission-essential tasks of a light infantry battalion is to conduct a “movement to contact,” defined in Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 3-21.20, Infantry Battalion, as “when the enemy situation is vague or not specific enough to conduct an attack.” To be glib, hyperbolic, and reductive, the operational construct here can be simplified as “walk around until you bump into something.” With the absence of dedicated battalion-level intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), light infantry battalions have little choice but to do exactly that. The combat platforms in armor and Stryker formations have the long-range sensors necessary to find, fix, and destroy enemy formations from kilometers Photo courtesy of authors Soldiers in Mortar Platoon, Headquarter and Headquarters Company, 1st away, a capability severely lacking across the light Battalion, 175th Infantry Regiment, fire 120mm mortar training rounds for effect infantry battalion. However, light infantry battalions during the unit’s 2018 annual training at Camp Guernsey, WY. fighting in severely restricted terrain do not require The battalion fires cell and mortar platoon would remain bulky, power-intensive, line-of-sight optics. Light infantry largely unchanged, save for the aforementioned removal battalions require their own solutions, solutions optimized of the 120mm mortar mission and equipment. Placing all for close-range combat in severely restricted terrain. Much of the battalion-level indirect fires professionals under one like the Hawkeye, SUAS represent a novel capability that the formation allows for a greater level of synchronization than Cold War-era U.S. Army lacked and provide another way in currently exists. The Hawkeye platoon would consist of three which ground combat can be reimagined in the current great Hawkeyes, a HMMWV-mounted Fire Direction Center, an power competition (GPC) era. additional ammunition-hauling HMMWV, and other nominal SUAS are particularly well suited for light infantry combat. equipment such as additional Advanced Field Artillery Tactical Instead of relying on scarce forward observer teams to Data Systems (AFATDS) and high frequency (HF) radios. stealthily insert and observe key terrain or named areas of The proposed Hawkeye platoon and battery command interest, the light infantry battalion can and should litter the structure would only add an additional 23 personnel to each battle zone with low-cost, easily employed SUAS to find, battalion (12x 13B, 4x 13J, 3x 13A, 1x 13Z and an additional fix, and destroy the enemy. SUAS enable close-in, beyond 3x 91F Soldiers in the FSC), representing a force-wide line-of-sight observation to allow light infantry to identify and growth of just over 3,100 personnel. Currently existing field engage targets that would nominally threaten a mounted platartillery force structure should not serve as the bill payer for form but would significantly challenge a dismounted element. this growth. However, given the zero-sum nature of Army The SUAS capability is specifically unique in its ability to revoforce structure, eliminating one of the M119 batteries from lutionize the light infantry. While the flying speed of the Raven the IBCT’s field artillery battery could potentially serve as one barely exceeds that of a mounted platform, it far exceeds bill payer. Alternatively, acknowledging the increased lethality that of dismounted light infantry. Furthermore, dismounted this capability would represent for light infantry battalions and light infantry can carry the 4.2-pound Raven on missions to brigades, this growth could be offset by a reduction in light dynamically employ the SUAS as mission conditions dictate. infantry forces themselves. The modified tables of organization and equipment Field artillery assets combined with the unique technical (MTOEs) for U.S. Army maneuver battalions of all types list capability that SUAS provide have the potential to funda- the RQ-11 “Raven” SUAS as required equipment. However, mentally change ground combat much like machine guns, those MTOEs fail to code any Soldier by duty position or armored vehicles, or airplanes have in the past. Many major additional skill identifier (ASI) as a battalion master SUAS conflicts are presaged by a smaller, regional conflict — the trainer or company-designated unit SUAS operator. While Mexican-American War before the Civil War, the Boer War this provides flexibility for small unit commanders, it also prior to World War 1, or the Spanish Civil War before World represents a vacuum of guidance in how to satisfy an underWar 2. In each “pre-conflict,” technological innovations drove resourced requirement. Commanders must independently significant changes in tactics and techniques. Success in the determine how many personnel to dedicate to this essential 22 INFANTRY Spring 2022 skill and have no authoritative document with which to justify the allocation of scarce training dollars. To solve this problem, commanders have two possible solutions: permanently remove a Soldier from a subordinate squad (thus reducing its combat power) or engage in a perpetual game of tug-ofwar within their own formations, forcing a Soldier to attempt to simultaneously master two skills at once. Armored cavalry squadrons and combined arms battalions have a sergeant in the battalion S2 section with the “Q7” additional skill identifier, denoting the completion of the Information Collection Planner Course (presumably denoting a capacity for SUAS integration). However, the light infantry battalion lacks any doctrinal or MTOE-designated battalion-level staff member as the battalion-level SUAS integrator. As a result, light infantry battalions are particularly disadvantaged and must develop grassroots, ad hoc solutions to integrating company-level SUAS collection into the larger battalion intelligence picture with varying levels of efficacy. The Army should immediately add the “Q7” capability to all light infantry battalion S2 shops that have or may have subordinate units enabled with SUAS to enable better SUAS integration into battalion tactical plans. In another battalion-level inconsistency, the scout platoons of combined arms battalions are authorized Raven SUAS, but light infantry battalions are not. As a result, light infantry formations face the decision to either reduce the potential reconnaissance reach of their scout elements or reduce the capability from a line company. Simple parity would demand that the Army should add at least one additional SUAS to these formations. However, parity is insufficient; light infantry battalions should be furnished with multiple SUAS platforms per company. The goal of a light infantry battalion should be to find, fix, finish, and destroy the enemy to the greatest extent prior to securing the objective. Greater SUAS density and integration at the battalion level — combined with robust, battalion-led fires — provide the light infantry battalion the ability to shape the battlefield to a heretofore unimagined extent. The goal of an infantry battalion should not be to fight and die every inch of its way onto a contested objective; it should be to rapidly occupy a devastated enemy battle position, destroy minimal residual resistance, and seize terrain for transition to stability or defensive operations. The potent combination of multiple SUAS platforms combined with on-call fires would enable the light infantry battalion to do so. In a future near-peer fight, the U.S. Army can expect to fight in a markedly different environment than existed during the Cold War or GWOT. Instead of reverting to the construct from the last era of GPC, a third approach to fire support must be implemented, an approach better suited to the acknowledged challenges the Army may face. Degraded communications and isolation in an air denial environment would pose a challenge for maneuver forces writ large, but pose an especially acute danger for light infantry forces when arrayed against our imagined foes. SUAS platforms provide a capability for light infantry formations to identify enemy positions well before a movement to contact would accidentally uncover them. Light infantry formations are inherently vulnerable and can rapidly become a liability on the future battlefield if not furnished with the appropriate resources. Devolving greater indirect fire capability directly down to the light infantry battalion, combined with the SUAS platforms and integration necessary to maximize the utility of that firepower, will allow these formations to gain and maintain the initiative on the battlefield — even when geographically or electromagnetically isolated — in order to help higher echelon commanders to press the advantage and defeat our opponents. Notes Michelle Tan, “Army Chief: Soldiers Must Be Ready to Fight in ‘Megacities,’” Defense News, 5 October 2016, accessed from https:// www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/ausa/2016/10/05/ army-chief-soldiers-must-be-ready-to-fight-in-megacities/. 1 CPT Samuel P. Wiggins is a 2012 graduate of the Salisbury University Army ROTC program who currently commands Company B, 1st Battalion, 175th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT), 28th Infantry Division. His previous assignments include serving as battalion fire support officer (FSO), Detachment 1, Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 1st Battalion, 107th Field Artillery Regiment, 2nd IBCT, 28th ID; and executive officer (XO), mortar platoon leader, and company FSO for Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1-175th Infantry. LTC Alexi D. Franklin currently serves as the National Guard Liaison Officer to Joint Task Force - National Capital Region. LTC Franklin’s previous Infantry assignments include serving as the XO of 1-175 Infantry, 2nd IBCT, 28th ID; commander of C Company (Long Range Surveillance), 158th Cavalry Squadron, 58th Battlefield Surveillance Brigade; and a variety of company-grade leadership and staff assignments with the 173rd Airborne Brigade. Commissioned through ROTC in 2005 from Johns Hopkins University (JHU), he holds a bachelor’s degree in political science and master’s degree in government from JHU, a master’s in business administration from Mount St. Mary’s University, and a master’s degree in defense and strategic studies as a National Defense University Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction graduate fellow. Photo courtesy of authors A Soldier with 1st Battalion, 175th Infantry Regiment launches a Raven small unmanned aerial vehicle during a training event. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 23 PROFESSIONAL FORUM Senior NCOs at Points of Friction CSM NEMA MOBARAKZADEH I n 1815, the British Army, led by Lieutenant General Pakenham, suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of New Orleans. In preparation for the battle, the American forces created a large trench and a seven-foottall rampart that ran from the bank of the Mississippi River to a swampy area to the northeast.1 On the west bank of the Mississippi, a battery of American artillery oversaw the battlefield. The British Army planned to send a formation to seize the American battery and then attack the trench using two columns of Soldiers. The first column’s attack failed when the commander died, leading to a disorderly retreat. The unit responsible for emplacing ladders and fascines was late, delaying the second column. Pakenham chose to personally retrieve the unit, leaving the rest of the formation without a commander. In Pakenham’s absence, a subordinate commander decided to reinforce the position, resulting in half of the formation dying and later Pakenham himself. It is easy to imagine how the battle may have gone differently if the British had placed senior NCOs at crucial locations. A senior NCO could have acted on Pakenham’s behalf, leaving him to command the second column or to reorganize the panicked first column. The Battle of New Orleans’s outcome may have been a British victory if Pakenham had better employed his NCOs. Friction Points,” Douglas R. Satterfield paraphrased Carl von Clausewitz: “The good general must know friction in order to overcome it whenever possible, and in order not to expect a standard of achievement in his operations which this very friction makes impossible.”2 While quoting Clausewitz may elicit eye rolls from some readers, the quote highlights an important question: How can a commander mitigate operational friction? Senior NCOs are adept at reducing friction. As respected members of an organization, senior NCOs can influence Soldiers and leaders through presence. To maximize their impact, senior NCOs must make deliberate decisions about where they position themselves on the battlefield, rather than relying on doctrinally suggested positions. Some senior NCOs struggle to identify points of friction or ways they can influence their formation. By understanding the operational plan, communicating with the commander, and applying a friction rubric, senior NCOs better posture themselves to make informed decisions. Additionally, understanding historic points of friction for common tactical operations will aid a senior NCO in identifying risk. Senior NCOs can maximize their operational effectiveness by carefully considering their optimal placement rather than arbitrarily going to where they are comfortable or have always gone. Senior NCOs play a critical role during combat operations. They benefit organizations in numerous ways, but identifying and lubricating friction points is one of their most critical functions. Like a Pro Bowl free safety, senior NCOs roam the field cleaning up mistakes. While officers and junior leaders position themselves to best control their element, senior NCOs should be at the point of maximum friction. Senior NCOs at points of friction free commanders to command the overall operation. Every mission has friction: operational risk due to adjacent unit convergence, complexity, enemy actions, poor planning, inadequate intelligence, or a lack of experience. Friction is often self-inflicted, desynchronizing an operation before the Photo by SGT Sarah D. Sangster enemy has voted. In his 2015 Soldiers in 2nd Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, prepare for a daytime air assault article “Identifying Strategic mission at the Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, LA, on 14 October 2020. 24 INFANTRY Spring 2022 Senior NCOs are Optimal for Lubricating Points of Friction Senior NCOs are generally among the most experienced Soldiers in a formation. The platoon sergeant (PSG), first sergeant (1SG), or command sergeant major (CSM) have years of experience and military education. Commanders expect senior NCOs to identify and solve problems during all phases of an operation. As seasoned Soldiers, they are calm in the face of adversity, thinking through problems as chaos ensues on the battlefield. Placing senior NCOs in the correct location on the battlefield can significantly reduce risk and optimize productivity. Leaders solving issues before they become an impediment to success can be the difference between success and failure. Placement of senior NCOs on the battlefield should be rooted in doctrine. The Army’s doctrine both directs and frees senior NCOs to find the best location for them to leverage their talents. Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession, establishes the leadership requirements model and identifies that leaders should possess the attributes of “character, presence, and intellect.”3 Simply put, senior NCOs cannot solve problems if they are not present. Senior NCOs build credibility when they demonstrate competence during routine functions and lower echelon training. Leaders are more apt to listen to a credible senior NCO. Doctrine suggests some locations where senior NCOs can position themselves. Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 3-21.8, Infantry Platoon and Squad, proposes that a PSG be at the support-by-fire (SBF) position or with the assault element. ATP 3-21.10, Infantry Rifle Company, recommends that the 1SG be heavily involved in medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) and sustainment operations. As NCOs move up the NCO support channel, their roles become more opaque. This ambiguity is liberating for senior NCOs, allowing the freedom to position themselves at the most critical locations. This freedom enables senior NCOs to have an enormous impact on mission success. A senior NCO from a higher headquarters (HQs) provides several advantages to the formation. A CSM can provide companies a fresh perspective and detect problems others do not see. Additionally, a CSM has access to more information, understands the larger operation, and has the means to affect other elements. The CSM is not directly responsible for controlling a specific element during an operation, which frees him or her to observe enemy actions, friendly elements, and battlefield effects. This freedom allows the CSM to keep formations on task and avert issues before they arise. The CSM will understand subordinate units’ strengths, weaknesses, and task proficiency. Senior NCOs’ positional power, and personal power built through previous engagements, allows them to provide instructions that Soldiers will follow without hesitation. While a 1SG from one company may hesitate to reposition his or her element at the request of another company, that same 1SG will move without question when ordered by the CSM. Senior NCOs are adept at risk management and intuitively understand how conditions As NCOs move up the NCO support channel, their roles become more opaque. This ambiguity is liberating for senior NCOs, allowing the freedom to position themselves at the most critical locations. This freedom enables senior NCOs to have an enormous impact on mission success. such as fatigue, darkness, terrain, and poor weather affect operations. The summation of a senior NCO’s intuition is a concept known as thin-slicing. Thin-slicing is a psychological methodology that allows people to dissect situations quickly and accurately. According to Jeff Thompson, PhD, thinslicing is when a person is “observing a small selection of an interaction, usually less than five minutes, and being able to accurately draw conclusions in the emotions and attitudes of the people interacting.”4 Senior NCOs regularly thin-slice situations by applying their breadth and depth of knowledge and experience. Some leaders mention a gut feeling or their “spidey sense,” but they are unknowingly referencing the thin-slice concept. Presence is necessary for thin-slicing to work. For example, a CSM walking through a vehicle marshalling area may identify a Soldier without a night vision goggle (NVG) mount on his or her helmet. The CSM can quickly surmise that the unit did not complete precombat checks (PCCs) and pre-combat inspections (PCIs) to standard. Understanding the risk of a driver or leader operating a vehicle in black-out conditions without NVGs will lead the CSM to investigate further. A small investment of time to scrutinize the depth of the problem, along with other potential safety shortcomings, could save Soldiers’ lives and prevent an accident that could derail the operational timeline and reduce combat power. Thin-slicing helps senior NCOs identify common points of friction. Methods of Identifying and Overcoming Friction Every operation has numerous points of potential friction, and they vary by phase. Senior NCOs can use differing tools and methods to identify and subsequently lubricate friction. Senior NCOs have to assess each potential point of friction to position themselves at the most critical location. Furthermore, CSMs must help coordinate subordinate senior NCO placement, ensuring adequate coverage of anticipated operational friction. In order to identify points of friction, senior NCOs must assess the overall operation. Senior NCOs should consider several criteria before deciding the maximum point of friction. Before they can decide where they should be, they must understand the plan and the commander’s intent. A senior NCO’s participation during the planning process can prevent problems later. Additionally, understanding the plan will allow the senior Spring 2022 INFANTRY 25 PROFESSIONAL FORUM Criteria Type of Operation Unit Proficiency SBF 1 1 3 1 Assault 3 2 1 2 Breach 4 4 2 4 MEDEVAC 2 3 4 3 Location Leader Risk Proficiency Mitigation Location 5 Location 6 Friction Rubric NCO to examine and weigh critical factors systematically. Much like a writing a college essay, a rubric or matrix can aid in determining points of friction (see table above). The friction rubric is a tool that helps leaders determine operational friction and, subsequently, senior NCO placement. An adapted decision matrix, the rubric weighs criteria across each considered location.5 The unit can score the rubric in either descending or ascending order. Identical to weighing courses of action during war-gaming, leaders can assign a multiplier as appropriate. The current conditions of the unit and environment may have negligible impacts on the considered locations. For example, if the unit is at full strength and rested, and the weather is favorable, then the concern is low. Conversely, a unit attrited to 75-percent combat power that has 50 percent of its combat load — in addition to the fact that it has moved a great distance over several days and it has now started to rain — will increase risk and need accounting for in the rubric. The rubric lists each criterion across the top of the rubric. The left column contains the tentative locations. This example scores friction in descending order, meaning the highest number contains the most friction. Since leaders are considering four locations, they assign each criterion a score between one and four. The highest score is the tentative location for a senior NCO. If the unit prefers, leaders can use probability and severity rather than a numbered score. Senior NCOs should determine evaluation criteria that will comprise their friction rubric. Much like the war-gaming phase of the military decision-making process, the commander’s planning guidance will help determine the weight of each criterion. It is best to start with the risk assessment. Senior NCOs should identify the most dangerous hazards and determine if the risk mitigation measures are adequate. Furthermore, senior NCOs should focus on who is supervising the mitigation measure. A clear sign of friction is where the risk assessment identifies the supervising individuals as all leaders, leading to an economic theory known as the tragedy of the commons.6 This theory asserts that a lack of ownership encourages others to neglect resources or tasks.7 If someone is directly responsible, the probability of comple26 INFANTRY Spring 2022 Conditions * if applicable Score 1 7 tion to standard increases. After assessing risk, senior NCOs should look where units converge. When units are in close proximity or share the same 1 9 terrain, there is sure to be friction. Whenever units rub, they 1 15 will create friction regardless of 1 13 the type of operation. Imagine two companies opening a breach in a wired obstacle so they can attack an objective. The S3 or commander will likely command and control (C2) the fight, but friction typically arises as the units converge. While a company understands the details of its portion of the fight and the concept of the adjacent unit, a CSM with an understanding of the whole operation can synchronize efforts directly at the point of friction. Delays in reporting and the chaos of battle can make it difficult for commanders positioned behind the fight to make effective decisions. A CSM at the breach site understands the current fight better and can direct spacing, force flow, and security; improve reporting; ensure all conditions are set; and immediately address issues as they arise. Senior NCOs must understand the capabilities of their units and leaders as well as the effects of the current fight. A unit and its leaders’ capabilities and limitations, the current environmental conditions, and the organization’s readiness can create or reduce friction. Continuing down the friction rubric, the senior NCO must understand the capability of the formation. The unit’s frequency and proficiency at completing the assigned mission will influence risk. Furthermore, the senior NCO should consider the competence and tendencies of the formation’s leaders. Additionally, the senior NCO must evaluate the unit’s current level of fatigue, assigned strength, maintenance, and weather conditions. Within the friction rubric, leaders summarize these factors under the conditions column. Finally, the type of mission is an important consideration. Each mission comes with a varying degree of difficulty and risk. The more demanding the mission, the more these factors will matter. After considering each criterion in the friction rubric, senior NCOs will have tentative locations that need leader supervision. The next step of determining senior NCO placement is a conversation with the commander. The commander understands the overall mission and has concerns about specific aspects of the operation. Senior NCOs, armed with an understanding of the mission and an assessment of potential friction, can have an informed conversation with their officer counterpart. Many command teams forgo this step. Officers often trust that their senior NCOs will select the correct location. While senior NCOs are experienced, they often lack repetitions at their current echelon. Imagine a newly assigned battalion CSM. He or she may be the most experienced 1SG in the battalion but does not have practice serving as the battalion CSM. Many senior NCOs revert to where they are most comfortable, or where tradition places them, rather than at the point of maximum friction. Understanding these factors, coupled with the commander’s concerns about crucial aspects of the mission, can lead the command team to a better decision. Another method is for commanders to ask themselves two questions: “Where do I have to be?” and “Where do I wish I could be?” They might have to be in the C2 aircraft during an air assault because it provides the most advantageous location to synchronize the fight; however, they may desire to be at the landing zone (LZ) because they know there will be two separate companies landing together with junior command teams. This is a potential location for the CSM. Ultimately, the command team should vet the CSM’s tentative location during the rehearsal. Rehearsals are a critical component of mission success. While the command team may have a specific location in mind for the senior NCO, the rehearsal may reveal a better location. Following the rehearsal, the most senior NCO should speak with subordinate NCOs about their placement. This conversation allows for proper dispersion of the most senior leaders across the battlefield. This is also an opportunity for the more senior NCOs to coach subordinates on discerning the maximum point of friction for their portion of the mission. After the mission, units should conduct an after action review (AAR). The AAR will reveal positive and negative aspects of the mission. The leaders should invest time in determining if senior NCOs were in the correct locations. During training, senior NCOs should experiment with their placement. Training at different locations will build experience and confidence, which allows leaders to make better decisions about where they should place themselves during future missions. The unit can use this information to inform future missions or drive preparation for collective training. CSMs must educate their subordinate NCOs before unit training. Leader professional development (LPD) sessions are a crucial component of NCO development. While LPD sessions often coach tactics, some sessions fail to discuss points of friction or NCO placement. Furthermore, NCOs should engage trusted mentors about NCO placement and methods of identifying friction. Finally, leaders should amend professional military education to coach officers and senior NCOs on methods of identifying and reducing operational friction. It is important for these NCOs to understand common points of friction during combat operations. Common Points of Friction There are many points of friction during combat operations. Newly promoted senior NCOs are often unsure of their place on the battlefield. Instead of thinking critically about the friction in the operation, they default to conventional wisdom such as the PSG is always at the SBF position or the 1SG should always remain at the casualty collection point (CCP). It is important to understand the positive and negative effects of positioning a senior NCO at a specific location. Additionally, senior NCOs must identify transition points where they can move from a lubricated friction point to the next area of risk. Considering these factors will allow them to maximize their impact on the operation. While a unit may conduct countless types of missions, this section will only discuss the friction found in some of the most common operations, starting with uncoiling from the tactical assembly area (TAA). Uncoiling from the TAA is time consuming, complicated, and dangerous. Uncoiling is rife with friction. A large collection of units, equipment, and vehicles, regularly operated by novice crews, converging in tight spaces lends itself to accidents. Movement plans are often inaccurate and lack detail, further complicating operations. Simply lining up a chalk or serial of vehicles can be difficult. Weather conditions, maintenance, radio communications, PCCs/PCIs, and information dissemination further complicate matters. Senior NCOs can solve problems by placing themselves at the points of friction. Placing an operations sergeant major in a staging area will significantly buy down risk. 1SGs and CSMs spot-checking vehicles, weapons, equipment, and observing ramp briefs can lead to positive outcomes. Similarly, many of these same concerns carry over to air assault operations. There are many factors to consider, but senior NCOs play a crucial role in keeping the operation safe and on time. Uncoiling is not complete until all units have unloaded in their area of operation. De-trucking, or unloading helicopters, is dangerous and can desynchronize an operation if executed poorly. Troop movement operations usually involve a strict timeline, allowing convoys or helicopters to deliver subsequent chalks or move to their next mission. Riding in a helicopter or in the back of a truck is disorienting, especially for sleep-deprived Soldiers. While unloading, Soldiers often become intermingled with other elements, move slowly to establish security, leave equipment behind, or move in the wrong direction. Taking too long to dismount causes supporting vehicles or aircraft to deliver other units late. There is risk of injury as Soldiers linger in the road and convoys attempt to maneuver. During combat training center rotations, it is common for brigades to take 24 hours longer than they planned to deploy their units into the area of operations. Senior NCOs at critical locations can greatly reduce friction in the operation. Senior NCO placement within an airlift or convoy, on an LZ or de-trucking point, and at link-up locations is essential. During field planning, senior NCOs are often unsure where they should be located. While a unit is planning, numerous operations or tasks occur simultaneously. Brigades and battalions are always in a state of planning while also conducting operations. Companies and platoons are normally either executing a mission or planning/preparing for an operation. Deciding where senior NCOs place their attention is challenging. Imagine a company in a patrol base conducting troop leading procedures while the company commander plans. The 1SG must supervise rehearsals, Spring 2022 INFANTRY 27 PROFESSIONAL FORUM solve problems and share information. CSMs have a positive impact on an organization when they visit units during combat operations. Through the churn of reporting, planning, and combat operations, information gets lost in the shuffle. This is also an opportunity for the CSM to serve as the “camp counselor” by smoothing over personality conflicts, allowing subordinates to vent, or vetting plans. A CSM’s presence can uncover problems the HQs personnel are unaware of, allow him or her to disseminate critical information, or return information to the commander. These engagements often U.S. Army photo uncover systemic problems. A command sergeant major assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division and Regional Command (South) For example, a company may speaks with an NCO during a battlefield circulation in Zabul Province, Afghanistan, on 8 April 2012. report it has not received any casualty replacements. The CSM may thin-slice the situaconduct resupply, spot check Soldiers and equipment, aid tion and determine the brigade replacement cell (BRC) is in planning, and enforce security, just to name a few responthe likely point of friction. While 1SGs must stay with their sibilities. How 1SGs split their time amongst their responsibilities is paramount. It is imperative the senior NCOs and company, the CSM can drive to the brigade support area and officers of the company discuss priorities and leader cover- investigate. Conversations at the mortuary affairs collection age for supervising tasks. A published timeline aids the 1SG point and the BRC may uncover transportation issues. CSMs can use their positional power to cobble together and lead in keeping track of inspection priorities. a convoy to deliver the replacement Soldiers. Additionally, Helping the staff plan is a complicated endeavor for CSMs can rectify shortfalls in the casualty replacement CSMs. Finding the right touchpoints during planning with process. Finally, savvy CSMs keep additional supplies in the commander and staff is difficult for CSMs as they often their vehicle to address emergent materiel concerns. have to spend time circulating the battlefield or reducing Senior NCOs often place themselves at doctrinally friction. CSMs must regularly speak with the commander, S3, and executive officer (XO) to understand priorities and suggested positions, such as the SBF position, rather than concerns. CSMs should be involved in the course of action the maximum point of friction during tactical operations. development and the war game, helping to vet feasibility and Many senior NCOs gravitate to the SBF position. This may offering practical solutions. The operation order brief is too be the best location for a senior NCO, but the decision late for a CSM to shoot holes in the plan. Additionally, CSMs should be deliberate. Leaders must consider the composican serve as a bridge between current operations and future tion, experience of the crews, complexity of the plan, and operations. Many plans fail because planners are unaware leader proficiency. A competent weapons squad leader of a unit’s current location, personnel status, and equip- can easily handle two machine guns but may struggle to ment readiness. Likewise, battle captains may direct units manage four machine guns, a sniper, and handheld mortars. or enablers to objectives that take them too far from future This complexity may require a senior NCO to synchronize mission locations, rendering the plan unfeasible. CSMs can the various elements. If not a senior NCO, the commander share information between the two teams, reducing friction. may have the best vantage point to see the entire fight, best Subsequent touchpoints with each warfighting function can control all of the elements, and employ enablers. Even a produce opportunities to share information, lubricate fric- company XO at the SBF can free the senior NCO to move to tion, or identify issues the CSM can rectify. The information other points of friction. garnered during planning and these staff engagements will Another common senior NCO location is at the CCP aid shared understanding as the CSM conducts battlefield or controlling the MEDEVAC process. MEDEVAC operacirculation. tions are complex and, if done poorly, can distract from the Battlefield circulation is a senior NCO’s opportunity to 28 INFANTRY Spring 2022 objective. Clearly, senior NCOs can aid MEDEVAC. While overseeing these operations is a common function of senior NCOs, this is not always the best place for them to be. For example, if the headquarters and headquarters company 1SG is very reliable, the battalion CSM may better serve the formation elsewhere. Many factors determine how complex MEDEVAC operations will be. The number of projected casualties, the distance of MEDEVAC, enemy array, number of competent medical providers, and unit leader proficiency are just a few considerations. 1SGs often place themselves at the CCP even though there are only a few casualties. They may better benefit their units by placing themselves at a greater point of friction. The 1SG can always move to the CCP if that becomes the greatest point of friction. Instead of focusing on MEDEVAC operations, 1SGs may help flow their company into an urban area and de-conflict units within the objective. After the objective is secure or the tactical situation permits, they can move to the CCP to take over the MEDEVAC process. Senior NCOs can greatly benefit the unit’s consolidation and reorganization. After heavy fighting, consolidating and reorganizing can become challenging. Finding defendable terrain, tying in adjacent units, distributing ammo, placing key weapons in advantageous positions, and all of the necessary tasks can become chaotic without supervision. CSMs can help units through this process with their experience and understanding of the larger mission. MEDEVAC operations may consume a 1SG’s attention. The CSM is free to help the company defend the seized objective and ready the formation for the next mission. Likewise, a PSG relieving the 1SG of MEDEVAC duties allows the 1SG to tend to the entire company. Consolidation and reorganization often includes planned resupply missions. Distributing supplies after establishing a hasty defense is complex and something a 1SG may need to oversee, rather than a supply sergeant. There are also numerous locations for a senior NCO during movement-to-contact missions. Controlling formations during a movement to contact can be difficult. Platoons or companies often cannot see each other because of the terrain, which presents further challenges when there are casualties. The company trains must stay far enough from the company to prevent enemy compromise, but this separation causes friction to C2 and security. The company trains frequently have the best communications, which requires a key leader to monitor and report from that platform. Movement through challenging terrain strains communication across the unit and with the higher HQs. Once a unit has reached its limit of advance, formations normally move into a hasty or deliberate defense. Finally, the unit will likely need a resupply, a common senior NCO task. There are many acceptable locations for a senior NCO, which vary by phase, during a movement-to-contact mission. The 1SG and CSM must decide where they can best help their unit by applying the friction rubric. Senior NCOs play an important role in a deliberate defense, but they often struggle to define their role. Senior NCOs can maximize their operational effectiveness by carefully considering their optimal placement rather than arbitrarily going to where they are comfortable or have always gone. While preparing a defense, several tasks are happening simultaneously: offensive operations in the disruption zone, engagement area development, planning, and refit. Enemy incursions often interrupt progress as the unit repels attacks and deals with casualties. Senior NCOs must help plan casualty evacuation (CASEVAC), MEDEVAC, and sustainment operations all while ensuring Soldiers complete maintenance. The organization must unload important equipment from the company trains (for example, Javelin missile launchers and chemical protective equipment). Senior NCOs link up with and guide delivery crews to unload class IV materials at planned obstacle sites rather than having the team carry the items a great distance. Before dig assets waste time on unsuitable positions, senior NCOs can help the commander vet and mark fighting positions. Subsequently, senior NCOs must inspect fighting positions and the distribution of key weapons systems. Finally, overseeing rehearsals and receiving back briefs from Soldiers on alert plans, engagement/disengagement criteria, CASEVAC procedures, and the process for passing friendly units through obstacles are paramount. Frequent communication between key leaders, applying the friction rubric, a detailed timeline, and thinslicing during inspections will inform senior NCOs where to place their attention. After the defense is established, senior NCOs must determine their role in fighting the defense. There are numerous points of friction in a defense. The natural position for a CSM during the defense is overseeing MEDEVAC operations. While MEDEVAC operations are worthy of a senior NCO’s attention, other facets of the mission may contain more friction. Elements in the disruption zone often return to supplement primary battle positions, causing a risk of fratricide. Senior NCOs can play an important role in de-conflicting these two converging units. Anti-tank engagements are critical in the defense and may need a senior NCO’s oversight. Soldiers must engage vehicles with the correct munition so the element has the appropriate munitions remaining to kill more significant threats. While subordinate leaders focus on their portion of the fight, they often lose sight of disengagement criteria. Disengaging from a primary position to an alternate fighting position can be disorganized and lead to additional casualties. Senior NCOs can help maintain security and direct fire and maneuver so the formation can occupy alternate fighting positions in an organized manner. Additionally, senior NCOs can help calm Spring 2022 INFANTRY 29 PROFESSIONAL FORUM and direct a formation in the event of a chemical attack. Finally, they can also play an important role in organizing elements to counterattack at the appropriate time. Using the friction rubric, conversing with the commander, attending rehearsals, and conducting battlefield circulation will inform senior NCOs of their optimal position. Task-organization changes often produce friction. Senior NCOs should be interested any time there is a taskorganization change. These changes are easy for a planner to write into an order, but they do not always account for the logistics of moving a formation. For example, a Sapper squad installing obstacles for a battalion will conduct strenuous manual labor for most of the day. Shortly after the squad finishes its work, the engineer battalion will move the squad to support another unit. When the Sappers arrive at the next unit, the leaders will expect them to start working immediately on their obstacles. No one considered that the squad is out of food, has not slept in 36 hours, is out of fuel, and low on ammunition. Task-organization changes add additional friction when they direct an element to traverse the battlefield across numerous unit boundaries. Whether it is a CSM at a tactical operations center or a 1SG on the ground, senior NCOs should involve themselves in task organization changes. Senior NCOs are responsible for inspecting and reporting the status of attachments when they arrive and depart. With countless points of friction during combat operations, senior NCOs must deliberately assess their location on the battlefield. Conclusion Senior NCOs influence operations in many ways. To maximize a unit’s effectiveness, commanders and senior NCOs must carefully consider where the formation’s most experienced leaders should serve during combat operations. While doctrine informs leader placement, commanders and senior NCOs apply the friction rubric, risk assessments, and understanding of operational risk derived from rehearsals to determine maximum points of friction. Senior NCOs improve their ability to assess friction by experimenting during training, participating in AARs, developing subordinates through LPD sessions, and coaching from mentors. Senior NCOs positively affect outcomes through presence and thin-slicing. Understanding historical friction points commonly found in routine combat missions will help 30 INFANTRY Spring 2022 senior NCOs determine where they can best ensure mission success. Senior NCOs can maximize their operational effectiveness by carefully considering their optimal placement rather than arbitrarily going to where they are comfortable or have always gone. Notes 1 History.com, “Battle of New Orleans,” 2019, accessed from https:// www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812/battle-of-new-orleans. 2 Douglas R. Satterfield, “Identifying Strategic Friction Points,” The Leader Maker: A Blog About Senior Executive Leadership, accessed from https://www.theleadermaker.com/identifying-strategic-friction-points/. 3 Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession, July 2019, 1-15. 4 Jeff Thompson, PhD, “Thin Slices & First Impressions,” Psychology Today (24 March 2012), retrieved from https://www. psychologytoday.com/us/blog/beyond-words/201203/thin-slicesfirst-impressions. 5 Field Manual (FM) 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations, May 2014. 6 Alexandra Spiliakos, “Tragedy of the Commons: What it is and 5 Examples,” Harvard Business School, 6 February 2019, accessed from https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/tragedy-of-thecommons-impact-on-sustainability-issues. 7 Ibid. CSM Nema Mobarakzadeh currently serves as command sergeant major of the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division at Fort Polk, LA. He is a graduate of Ranger, Sapper, Jungle, Airborne, Jumpmaster, Pathfinder, Reconnaissance Surveillance Leaders, and Military Free-Fall courses among others. Photo courtesy of the Joint Readiness Training Center Operations Group CSM Jeffrey Loehr from 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division, participates in live-fire training at the Joint Readiness Training Center on 28 March 2017. The Information Domain and Social Media SGM ALEXANDER E. AGUILASTRATT SGM MATTHEW S. UPDIKE A form of asymmetric warfare is waged against the United States and its citizens daily across multiple venues and platforms without reaching the threshold or definition of open conflict.1 That form of asymmetric warfare is disinformation. Disinformation erodes trust and the ability to establish a society with effective institutions to serve and protect. As a result, it is conceivable to assume that disinformation and its social-media venues are corrosives affecting the information domain. Much like the early stages of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), disinformation presents the United States with a cost-effective, low-effort tactical problem with a strategic consequence Graphic by Patrick Buffett manifested in national trust erosion. Social media is the preferred venue for foreign, domestic, and proxy enemies to engage the The U.S. Army faces the renewal of Army remotely with minor risk. great power competition with adversaries engaging in multiple domains, thus challenging the media as a tactical system in the new information domain. traditional definitions of war and peace and operating under Active measures in the realm of social media include the threshold that would warrant military action.2 influencing others in a coercive way; disinformation; politicalA few years ago, Frank Hoffman identified the “weaponization” of social media as playing perfectly into the concept of hybrid warfare: “[Hybrid warfare] incorporates a range of different modes of warfare, including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder.”3 Importance The information domain offers adversaries the ability to engage the U.S. Army with digital IEDs and erode trust between our military and the American people. Social media is the preferred venue for foreign, domestic, and proxy enemies to engage the Army remotely with minor risk. The information domain starts at the tactical level, and it is also a tactical commander’s responsibility to occupy it or otherwise relinquish key terrain to nefarious actors. However, there is a lack of concise guidance about information and the aspects of cross-domain warfare. The result is the effect of “paralysis by analysis” and the consequent disregard of social influence operations in what could be considered the tactical setting for the asymmetric gray zone; hybrid; or next-generation information warfare against the U.S. Army. Operational Environment Social media, as part of the information domain, fits perfectly as a tool to shape the information operational environment, coordinate efforts, and erode trust by antagonizing below the threshold of conflict.4 In the past, basic communication models included sender, receiver, transmission, medium, and message as separate components; however, due to advances in technology, the information domain now adds the Internet, radio waves, satellite communications, wireless networks, and social media to the previous media.5 As a result, the information domain will become the preferred operational environment by near-peer, extremist organizations, and domestic threats that cannot match the U.S. Army’s kinetic capabilities. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 31 PROFESSIONAL FORUM Example: ISIS in Mosul When the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) invaded Northern Iraq in 2014, it only had about 15,000 militants who picked up weapons and vehicles from the previous extremist groups. However, after introducing its hashtag campaign #ALLEyesOnISIS, it gained an extensive network of passionate supporters and Twitter bots to lock down other trending hashtags for Arabic-speaking users.6 ISIS’ on-line tactics and mastery of the information domain recruited from more than 100 countries and spread fear globally. The information domain as an operational environment is now a contested battlespace where various actors with realworld goals such as ISIS could use the same tactics with relative simplicity. For example, ISIS’s top recruiter, Junaid Hussein, used the same tactics that Taylor Swift used to sell her records.7 The acknowledgment of the changes in the character of warfare related to the information domain is evident not only to the military but also to corporations. Facebook, for example, is planning the creation of a “war room” to counter disinformation operations.8 Commanders at all levels deal with the challenges of the information domain, social media, and their formations. Social media is the ideal platform for information/disinformation, on-line communities, nefarious actors, inundation and targeting, and less-than-honest techniques. For example, during the last Mexican elections, one-third of the on-line conversations were generated by bots.9 Social-media platforms are addictive by design. Notifications, for example, do not tell the user what the subject is about, thus creating a certain level of anxiety and the need for closure, appealing to emotions. Unfortunately, our young generation of Soldiers is affected by this type of emotional targeting. For example, in Chicago, 80 percent of school fights originate from on-line comments. Gangs and extremist-organization recruiters stir negative emotions such as anger to disenfranchise and absorb young recruits. If units do not occupy and employ the information-domain operational environment, they risk enabling nefarious actors to target Soldiers, spread disinformation, and operate with impunity. Speed and Level of Response The need for a social-media presence as part of information-domain occupation is paramount for U.S. society and its symbiotic relationship of trust with its Army. One of the most efficient ways for commanders to occupy the information domain and counter disinformation is to practice consistent messaging, whether doctrine or science/fact-based. As social media continues to evolve with visual venues, including China’s TikTok, it is essential to point out that the enemy uses artificial intelligence and algorithms to flood the virtual battlefield. As a result, reliable information must be treated as a defensive/offensive weapon system and an area-denial tool against threat actors. 32 INFANTRY Spring 2022 The U.S. Army must recognize at echelon that social media can be used as a weapon of adverse effects; therefore, it must invest in social-media literacy and instill awareness of methods and goals of targeted campaigns by nefarious actors. The most effective tool against nefarious actors is an educated and empowered population of Soldiers and leaders capable of identifying and discrediting disinformation attempts. The U.S. Army must recognize at echelon that social media can be used as a weapon of adverse effects; therefore, it must invest in social-media literacy and instill awareness of methods and goals of targeted campaigns by nefarious actors. For example, Russia believes that the United States’ weakness is its diversity, so to counter this, the U.S. Army must show strength in its pluralism and pave the way to heal the divisions in our country by shielding our own culture. When the Army acknowledges social media as part of the information domain and develops an effective strategy, it will deny nefarious actors crucial terrain in the information environment. Changes in Technology The U.S. Army’s adversaries see information as a domain and all forms across platforms as potential venues of power ready to be weaponized. Near-peer threats also view all U.S. information-technology systems as vulnerabilities.10 As information technology evolves, so do its platforms (using TikTok as an example). Technological advances enable nefarious actors to manipulate media with artificial intelligence-enabled “deep fakes.”11 Tech companies are developing methods to reveal such deep fakes and image alterations that create anger and negative public opinion. Also, developers are working on their algorithms to counter those used by nefarious actors to discourage the practice of sharing misleading information based on the title alone. The algorithms will aid in creating a healthy level of skepticism, improving social-media literacy.12 Despite all advances in technology, the most important advance must occur within the human domain. The most effective tool to counter disinformation and divisionism is the educated and empowered U.S. Army, capable of discrediting disinformation and targeting efforts. In addition, the Army must inoculate its Soldiers against those who seek malign control of the information domain. Command teams must invest in social-media literacy and instill awareness, methods, and goals of targeted disinformation campaigns while measuring fissures in their information campaigns. Strategic Communications and Information Advantage The spread of misinformation and division is actually a “biohazard” that can spread throughout any formation if command teams do not effectively occupy the information domain. Command teams at echelon must define purpose with clarity and convey clear and concise messaging while considering the target audience and desired effects to counter or deny the enemy of crucial terrain to infect the information domain. Social media is an effective platform to inform Soldiers and families while combating disinformation. Also, young Soldiers, officers, and NCOs live in an era in which social media is essential in their lives. Humanizing the narrative to create positive effects within formations is critical for countering the infection created by the weaponization of social media. Units that humanize their narrative can use the information domain as a means for Soldiers to: • Know the unit’s purpose; • Communicate that purpose often and in different ways; • Make it personal by creating informal feedback loops; • Reinforce narrative with actions; • Give purposed-based feedback; and • Align behaviors with purpose. Pre, During, and After Action Plans Effective social-media communication provides command teams a venue to exercise information-domain advantage and deny nefarious actors key terrain and avenues to infect formations. Also, command teams and staff must have the capability to engage in contingency operations to inform or respond to emergencies before, during, and after crises. Time is of the essence, especially if that time is during a crisis. You will likely use social media and on-line platforms as the first resource to react and to put out information. Because social media provides speed, reach, and direct contact with audiences, it is a crucial tool to disseminate command information and provide a place to receive timely updates. Develop the social-media strategy as part of your crisiscommunication plan. Having a set strategy the team is comfortable with will help your unit better prepare and manage responses during a crisis. Command Presence and Talent Management Command teams must manage the information domain like any operational environment. Staff and senior enlisted advisers can help the commander navigate the complex environment using experienced members within their formation (Soldiers and civilians) who are talented and adept to the social-media environment. A candid, genuine command presence can help leaders define their expectations, style, and expectations to Soldiers and geographically displaced family members. Also, subordinate commanders can emulate a solid and genuine social-media command presence. Defining leader expectations for the information domain is as important and comparable to the four rules of a gun range: • Watch the muzzle and keep it pointed in a safe direction at all times; • Treat every weapon system as if loaded at all times; Spring 2022 INFANTRY 33 PROFESSIONAL FORUM Vignette: Social-Media Reputation Management and Response (10th Mountain Division Shoothouse Incident, 21 February 2021) A bodycam video of Soldiers conducting live-fire close-quarters battle training displaying many safety violations began circulating on the Internet. It claimed that the Soldiers belonged to 10th Mountain Division. Staff from the 10th Mountain determined the Soldiers were from the division but not the unit they belonged to or how long ago the training occurred. Measured response: Within 24 hours, the video had gone viral. Through contact with the meme pages from the energy-drink rumor, CSM Mario O. Terenas, 10th Mountain’s top enlisted Soldier, eventually determined the exact unit in the shoothouse and the training time. Rather than send out an old-fashioned press release, he addressed the allegations in a one-minute response video on all his social-media accounts. He admitted that the Soldiers belonged to 10th Mountain Division and was saddened by what he saw. However, he assured the audience that was not the unit’s standard and he would fix the problem. Results: CSM Terenas’ video received an overwhelming amount of audience engagement. Users commended Terenas for owning up to the allegations instead of trying to hide from them. His video went viral almost immediately after being released (152,000 views on Twitter, 86,000 Instagram views, and 1,000 on Facebook). • Positively identify the target and the backdrop; and • Keep your finger off the trigger until ready to engage. Social media is an excellent medium for sharing information and reaching out to otherwise geographically displaced personnel; however, it is also a target-rich environment for nefarious actors. As a result, a strong command presence, coupled with action plans and expectations, is required to protect command integrity and safeguard Soldiers and families from the effects of disinformation and deliberate targeting. Threats Foreign. Open-source intelligence indicates that foreign actors are engaging in covert information operations against the United States. Disinformation is not a new concept. Russia has a long history of seeking to project power and influence while playing to our potential technological and geopolitical handicaps.13 Without the equivalent conventional might of the United States, Russia, China and other nations recognize our appetite for information. They use social media as a platform to exercise tactics of influence, coercion, and the capability to 34 INFANTRY Spring 2022 control the narrative, thus manipulating a specific population’s hearts and minds.14 The diverse, pluralistic, and democratic nature of the United States makes it a target-rich environment of socialmedia-empowered Russian disinformation. As a result, the all-volunteer force composed of free citizens of a diverse nation offers the same opportunities for a country that has long fought to rebalance power.15 At the macro level, Russia has realized U.S. conventional superiority, with General Valery Gerasimov’s doctrine revolving around information control as the key to victory. The Gerasimov Doctrine — or Russian new-generation warfare — advocates simultaneous operation and control of the military, political, cyber, and information domains, which can be accessed employing social media.16 Gerasimov also made the following statement about information technology: “Information technology is one of the most promising types of weapons to be used covertly not only against critically important informational infrastructures but also against the population of a country, directly influencing the condition of a state’s national security.”17 Russia operates under the concept that the distinction between war and peace no longer exists and uses misinformation to protect itself from a military response. In essence, once it has started, Russia must maintain momentum since it acknowledges that the United States’ advantages in information technology will undermine Russian social, cultural, and political institutions if pushed beyond the threshold of conflict.18 China also seeks to influence the American public, although its approach differs widely from Russia’s tactics. A Recorded Future article stated: “We believe that the Chinese state has employed a plethora of state-run media to exploit the openness of American democratic society in an effort to insert an intentionally distorted and biased narrative portraying a utopian view of the Chinese government and party. ...what distinguishes Russian and Chinese approaches are their tactics, strategic goals, and efficacy.”19 A paper published by the Hoover Institution in November 2018 included findings from more than 30 of the West’s preeminent China scholars, collaborating in a working group on China’s influence operations abroad. The scholars concluded: “[T]his report details a range of more assertive and opaque ‘sharp power’ activities that China has stepped up within the United States in an increasingly active manner. These exploit the openness of our democratic society to challenge, and sometimes even undermine, core American freedoms, norms, and laws.”20 “The Russian state has used a broadly negative, combative, destabilizing, and discordant influence operation because that type of campaign supports Russia’s strategic goals to undermine faith in democratic processes, support pro-Russian policies or preferred outcomes, and sow division within Western societies. Russia’s strategic goals require covert actions and are inherently disruptive, therefore, the social-media influence techniques employed are secretive and disruptive as well. The Chinese state has a starkly different set of strategic goals, and as a result, Chinese state-run social-media influence operations use different techniques. [Chinese President] Xi Jinping has chosen to support China’s goal to exert greater influence on the current international system by portraying the government in a positive light, arguing that China’s rise will be beneficial, cooperative, and constructive for the global community. This goal Graphic by Regina Ali requires a coordinated global Military experts are constantly warning service members about social media scams. message and technique, which Russia employs tactics such as those used against Africanpresents a strong, confident, and optimistic China.”21 The relentless need to maintain the social media and Americans in advance of the 2016 election and the exploitaflooding Twitter disinformation continuum of operations under the destabiliz- tion of the Black Lives Matter movement by 24 hashtags and diluting legitimate concerns. ing Gerasimov Doctrine enables Russian tactical commanders to conduct offensive cyber and information operations. In contrast, U.S. tactical commanders lack clear social-media guidance at the tactical level. It is fair to conclude that a Russian tactical commander is more empowered to conduct offensive information operations than a U.S. tactical-level commander due to the protection of several disinformation layers. As a result, Russian tactical-information units and their proxies occupy the proverbial “high ground” of the information domain. Modus operandi. Western newspapers once described Russian President Vladimir Putin as “the cold-eyed ruler of Russia,” “a cold, calculating … spy who sought to undermine freedom in the West.” With “his dark past, his sinister look,” he was “straight out of KGB central casting.”22 Thus one could say that Putin is the spy who would be king. As such, he understood that once he embarked on the Gerasimov Doctrine, his methods for occupying the information domain would become predictable. As a result, the need for relentless action at the tactical level would become the Russian apparatus’ cornerstone. Therefore Russia’s social-media exploitation method is predictable. They identify a contentious issue, employ bots and trolls on various social-media platforms to spread divisive messages, and amplify discord.23 In addition, a diverse U.S. Army, recruiting from a pluralistic society dealing with societal fissures and racial tension, creates opportunities for Russian disinformation attacks against the foundations of trust between the U.S. Army and the American people. In the case of creating friction against the U.S. Army, The need for a response and occupation of the information domain becomes prevalent when the Russian threat recognizes the need to identify, exploit, and amplify U.S. political tensions, racial wounds, and the promotion of health scams (anti-vaxxer movement) in a divisive and emotional manner. Domestic. On-line social-media platforms are playing an increasingly important role in the radicalization processes of U.S. extremists. While U.S. extremists were slow to embrace social media, in recent years the number of individuals relying on these user-to-user platforms to disseminate extremist content and the facilitation of extremist relationships has grown exponentially. In fact, in 2016 alone, social media played a role in the radicalization processes of nearly 90 percent of the extremists in Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States data. Social media exists for the extremist the same way it exists for the everyday user, neither evil nor benevolent. Socialmedia sites are simply a method extremists use to conduct a myriad of organizational functions. Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube are the most popular social-media sites today, but that does not mean they will stay on top. Tumblr, LinkedIn, Google+, and Instagram are all social-media sites growing in popularity. Command teams and staff must acknowledge and keep abreast of new advances in social media.25 However, it must not consume their time, nor should they neglect professional distance, but rather consider social media as part of the information domain. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 35 PROFESSIONAL FORUM Notes Recorded Future, “Beyond Hybrid War.” Greg McLaughlin, Russia and the Media: The Makings of a New Cold War (London: Pluto Press, 2020); retrieved from http:// www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvzsmdt1. 23 Gamberini, “Social Media Weaponization.” 24 Ibid. 25 U.S. Air Force MAJ Joshua Close, “#Terror: Social Media and Extremism,” paper for graduate requirements, Air Command and Staff College, May 2014. 21 Sarah Jacobs Gamberini, “Social Media Weaponization: The Biohazard of Russian Disinformation Campaigns,” Joint Force Quarterly, 4th Quarter 2020. 2 Ibid. 3 Frank Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Warfare (Arlington, VA: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007), cited in Dr. Ofer Fridman, “The Danger of ‘Russian Hybrid Warfare,’” Cicero Foundation Great Debate Paper, July 2017. 4 Gamberini, “Social Media Weaponization.” 5 Robert Kozloski, “The Information Domain as an Element of National Power,” Center for Contemporary Conflict, 2020. 6 The University of Pennsylvania, “Why Social Media is the New Weapon in Modern Warfare,” Knowledge@Wharton interview with P.W. Singer and Emerson T. Brooking, 2019. 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid. 9 Ibid. 10 Gamberini, “Social Media Weaponization.” 11 Ibid. 12 Ibid. 13 Ibid. 14 Ibid. 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 Dr. Harold Orenstein and LTC (Retired) Timothy Thomas, “The Development of Military Strategy Under Contemporary Conditions: Tasks for Military Science,” Military Review, November 2019. 18 Gamberini, “Social Media Weaponization.” 19 Recorded Future, “Beyond Hybrid War: How China Exploits Social Media to Sway American Opinion,” 6 March 2019, accessed from https://www.recordedfuture.com/china-social-media-operations. 20 Larry Diamond and Orville Schell, eds., “China’s Influence & American Interests: Promoting Constructive Vigilance,” The Hoover Institution, 29 November 2018, accessed from https://www.hoover. org/research/chinas-influence-american-interests-promotingconstructive-vigilance. 1 22 Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in the Winter 2022 issue of Armor. SGM Alexander Aguilastratt is an Infantry Soldier assigned as the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) projectinclusion sergeant major at the Pentagon, Washington, D.C. His previous assignments include serving as command sergeant major, U.S. Southern Command, Soto Cano Air Force Base, Honduras; command sergeant major, Charlie Squadron, Asymmetric Warfare Group (AWG), Fort Meade, MD; and sergeant major, Baker Squadron, AWG, Fort Meade. His military schooling includes the U.S. Army Sergeant Major Academy, Vulnerability Assessment Methodology Course, AWG Operational Adviser Training Course, Master Resiliency Course, Joint Readiness Training Center Observer-Controller Course, Reserve Officer Training Command Course, Air Assault School, Airborne School, and Jumpmaster Course. SGM Aguilastratt earned a master’s degree in international relations and affairs from Liberty University and a bachelor’s degree in business administration in liberal arts (graduated summa cum laude) from Excelsior College. SGM Matthew Updike has a scout background. At the time this article was written, he was assigned to G-3/5/7, TRADOC, Fort Eustis, VA. His previous assignments include serving as command sergeant major for deputy director, Noncommissioned Officer’s Professional Development Directorate, NCO Center of Excellence, Fort Bliss, TX; brigade command sergeant major, Task Force Sinai, Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt; and command sergeant major, 3rd Squadron, 71st Cavalry Regiment, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division, Fort Drum, NY. His military schooling includes the Scout Leader Course, security force assistance advisor training, Sergeants Major Course, and Maneuver Battalion and Brigade Pre-Command Course. SGM Updike earned an associate’s degree in business and administration and a bachelor’s degree in business and management from Excelsior College. New from the Center For Army Lessons Learned Handbook 22-663: Call to Action: Suicide Prevention — Reducing Suicide in Army Formations, Brigade and Battalion Commander’s Handbook The purpose of this handbook is to thoroughly examine, from a leadership perspective, the fundamental concepts and engagement necessary to develop and execute an effective suicide prevention program. The suicide prevention framework utilizes visibility tools, which assess risk and protective factors. The suicide prevention framework also establishes a unit forum to operationalize the suicide prevention program through the operations process. There is no single action that can prevent suicide. However, leaders who apply consistent and systematic whole-of-person approaches can positively impact individual and unit readiness. This handbook presents a vision of an Army built on a culture of trust. Soldiers can build strength and confidence in each another through the application of these principles, practices, and qualities. Suicide results from complex, interrelated factors, and therefore prevention must be comprehensive. This handbook describes the strengthening influence of recognized protective factors in many facets of Soldiers’ and Army families’ lives. Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited No. 22-663 NOV 2021 Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited Find this publication online at https://usacac.army.mil/organizations/mccoe/call/publication/21-14. 36 INFANTRY Spring 2022 Army Aviation — Above the Best! Now Let’s Train Together CPT DANIEL VORSKY W e live in trying times, and technology has facilitated the dissemination of doctrinal, tactical, and intellectual enhancements to the profession of arms. Not all changes are to our advantage, however, but as we adapt our tactics, techniques, and procedures to meeting the challenges posed by former near-peer adversaries we learn more about them as well. Army Aviation is a valuable adjunct to the combined arms team, and we need to learn how we can combine our capabilities to overcome the challenges posed by the enemy. The overall purpose of this article is to assist Infantry leaders with tools and tips to accomplish training objectives and build a better rapport with aviation assets, and most importantly, remove misconceptions surrounding the Army Aviation Branch. In my short decade in the Army, I’ve been blessed to do and experience quite a bit. I’ve learned how to fly helicopters and planes and train with the finest Soldiers the world has ever seen. With that being said, Army Aviation’s sole purpose is to support the ground force commander and support ground forces as a whole. Consequently, I am left to wonder why the majority of aviation training missions are flown without the ground force on board and why most of the submitted mission requests from ground forces aren’t supported. The following are some tips, tricks, and a general and informal guide to working with Army Aviation. Hopefully, this article will give ground forces a better understanding of how aviation units operate and the best ways of getting your training requirements and mission requests accomplished. Understanding No, we cannot take an aircraft out whenever we want to. Yes, we do have other requirements outside the cockpit. Yes, we wear different uniforms. Yes, crew rest is a REAL thing. Now that I have addressed some common stereotypes about aviators, let’s get down to discussing how you can maximize your opportunities to get a ride from us. After spending almost 10 years in the branch, I’d like to stress that Army Aviation and aviators are NOT better; we’re different — the same way the Infantry is different from Armor and every other branch. Please understand that we WANT to help you, we WANT to fly, and we ARE going to do pretty much everything within our power to accomplish the task and get the blades spinning to get off the ground. Aviators have flight requirements and regulations that have to be followed. If we don’t have crew rest, good weather, realistic expectations, and shared understanding, the mission is simply not going to happen. Like with any other branch, aviators have training outside of the cockpit that must be accomplished, and unfortunately, this removes us from the cockpit, which reduces the number of people we have able to achieve the mission. With other tasks comes the start of the duty day. Please understand that crew rest is for everyone’s safety, as I’ve lost more friends than I’d like to admit due to pilot error tracing back to pilot fatigue or pushing the envelope too far to complete the mission for the client. Weather No, we cannot just take off if there’s terrible weather. No, we cannot just hover at 6,000 feet and lower ourselves vertically to the ground. No, the weather has not changed in the five minutes since you called last. No, we cannot easily or quickly shift the mission 10 hours to the right because the weather might be better, requiring another crew. While this might seem simple, there is a lack of understanding of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations and Army Regulation 95-1, Flight Regulations. To put things simply in regards to weather, if we have to take off under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), we are more than likely taking off and flying point to point. In other words, we’ll be flying airport to airport, and we won’t be able to land at a random field in the middle of a training area. To put it in perspective, IFR flying is like driving a car, only looking at your dashboard and never looking outside. Aviators operating under IFR conditions are essentially flying blind, relying on their airframe’s instruments to provide the necessary information to fly. IFR flying makes special requests and many training requirements impossible to accomplish. After all this is said, follow the go/no-go times. I can honestly say there is nothing worse than having a client set a go/no-go time and not follow it. When the timeline gets pushed to the right, the arrival time most likely doesn’t change, so all it means is all things have to move quicker and faster, which generally creates a hazardous situation and will most likely not get approved by the pilot’s briefer. The last major factor with weather is we are NOT allowed to shop for the weather. Shopping for weather is when pilots call different weather briefers to get more favorable conditions for the exact same weather outside; again, it ends with an aircraft crashing. Realistic Requests No, we cannot do auto-rotations with an entire cabin of passengers. No, we cannot land wherever we want. We most likely cannot land in that tiny area that would barely fit our aircraft but would be more convenient. Just like anything else, be reasonable with your requests Spring 2022 INFANTRY 37 PROFESSIONAL FORUM for aviation support. We cannot drop everything to make a mission happen just because the “good idea fairy” struck at the last minute. Aviation operations require pilots, crews, ground crews, flight operations, and permission, often necessary from outside our battalions and brigades. Come with several courses of action on where you’d like us to land or options on how to accomplish your requirements. To the extent possible, know the aircraft limits of what you’re requesting: A UH-60 Black Hawk cannot lift the same as a CH-47 Chinook helicopter, and a CH-47 cannot land in the same area as a UH-60. Each airframe is different and brings something different to the table, and to that end, if you are given less aircraft than you wanted, please don’t scrap the mission because things aren’t exactly what you wanted. Ask to see the unit’s risk common operational picture (R-COP) and the Department of the Army (DA) Form 5484-R, as these documents are what all aviators use to get their missions not only approved but see the risk level of what is being requested. If the request comes in as high risk, drop it — no training mission is worth the loss of life. Chances are high that if you tell us what you need to be accomplished, we can suggest modifications to your plan to lower the risk and still achieve your training objectives. Forge a Bond Yes, most of us have great hair (not including myself). Yes, we say clear right and clear left when driving cars. No, the flight vest isn’t going anywhere and not all of us wear aviator sunglasses. We are all Soldiers in the Army and want to help. Come visit the airfield. The best way for your missions and requests to be accomplished is to know your aviation unit. I’ve never met an aviation unit that didn’t want to show off their aircraft, talk capabilities, and have a reason to spin blades. I honestly cannot stress this enough: We WANT to fly your mission, make the client happy, and WANT your mission/training to succeed. All of these driving factors start with the communication between the client and the aviation unit. Let us know what 38 INFANTRY Spring 2022 you’d like and what you’d settle for, so we can come up with a plan to accomplish the task at hand. Most importantly, be the unit that aviators want to work with. In other words, don’t insult or belittle the pilots when weather or operational constraints don’t work in your favor; nothing kills the bond between aviators and ground forces faster than that. Conclusion “Above the Best” is the Aviation Corps’ motto as we know the clients we serve are the best in the world. We want a reason to fly and want YOU to give us a reason to get the birds off the ground. Everything stated in this article is from events I have personally encountered and/or seen in my 10 years in Army Aviation. Hopefully, this article provides some insights that can aid ground forces as they seek to work with aviation more frequently. As the adage goes: the more we sweat together in peace, the less we bleed in war. When the military is focusing on preparing for large-scale combat operations, ensuring that a smooth working relationship exists between aviation and ground forces could not be more critical, and training is where this all begins. CPT Dan Vorsky currently attends the Military Intelligence Captains Career Course at Fort Huachuca, AZ. He has served as a pilot in command and air mission commander (UH-60A/L). His assignments include serving as commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 12th Aviation Battalion, The Army Aviation Brigade (TAAB), Fort Belvoir, VA; executive officer (XO) for Bravo Company, 12th Aviation Battalion, TAAB; XO for Foxtrot Company, 3-2 General Support Aviation Battalion, Camp Humphrey, South Korea; and platoon leader in A Company, 1-150 Assault Helicopter Battalion, Joint Base McGuire-Dix, Lakehurst, NJ. He earned a bachelor’s degree in maritime studies and a master’s degree in international transportation management from SUNY Maritime College, and is pursuing a doctoral degree in strategic leadership with Liberty University. Soldiers in the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) supported by rotary wing assets from 3rd Combat Aviation Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division conduct air assault operations during a field training exercise at Fort Knox, KY, on 2 December 2018. Photo by CPT Justin Wright Using Goals to Develop Subordinates CPT JACOB MOOTY “What are you doing after you get out?” “Going back home.” “Do you have a job lined up?” “I’m going to college.” “That’s great, which one?” “Probably the community college.” “So you haven’t applied anywhere yet… do you know what do you want to study?” “I’m thinking I’ll just knock out general classes first.” “What degree do you want?” “Um... business?” “What do you want to do with that?” (Conversation devolves into awkward eye contact.) I f I had a nickel for every time I’ve had the above conversation with an ETSing Soldier, I’d probably be pushing a dollar. Small change, but it breaks our hearts as leaders and mentors when service members leave the Army without a plan. We shouldn’t be surprised though. Many of our Soldiers seem to listlessly drift from job to job without thinking about what they want out of a career or even just a single enlistment. A lot of potential goes completely unrecognized because individuals simply don’t have anything they are working towards beyond the next paycheck. As leaders, I believe some of our duties are to gauge that untapped potential and ensure that our Soldiers are serving in a capacity that allows them to get the most out of their service. We’ve all heard of the SMART goals acronym (specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and timely) and know how to make our own goals using it, but do you know what your subordinates’ goals are? Have you ensured that those goals are SMART? And most importantly, are you developing your subordinates towards achieving those goals? When I first commissioned, I had a vague sense of what I wanted to do with my career but no clear definition of success or idea of how to get there. Fortunately for one 2LT Mooty, my battalion commander didn’t just ask his lieutenants for a single SMART goal, he asked for 12 of them: personal goals, professional goals, physical fitness goals, and financial goals. Each category required a near-, short-, and long-term goal. Your near-term goals are within a year, your short-term goals are within five years, and your long-term goals are beyond five years. After completing my platoon leader and executive officer (XO) time, I was the “new-lieutenant sponsor” (now a nickel for every made-up additional duty…). Part of my duties was helping new LTs develop their goals prior to initial counseling with the battalion commander. Almost every one of them had a goal along the lines of “I want to max the ACFT (Army Combat Fitness Test).” I sincerely hope you all recognize this as a bad goal — not a bad desire but a bad goal. Let’s make it into a good goal using the SMART acronym. First, this is not a specific goal. The ACFT has six sub components, and they intentionally have little overlap when it comes to muscle groups and how we use those muscle groups. To better specify this goal, we’ll say that the subject is unable to achieve the Army leg tuck standard. To better specify their goal, we’ll switch it from a broad scope to a narrow, specific one: I want to max the ACFT leg tucks. Next, we need to describe how we will define success. Yes, maxing the leg tucks can be measured by, well, maxing. But by not refining this measure, we have a narrow but scary goal. We can’t measure our progress. To make this goal measurable, we amend it to say: I want to max the ACFT leg tucks by improving my rep count to 20 reps. Now we’re getting somewhere. However, this goal still has a way to go. What are we going to do to get to 20 reps? I don’t think I’m being too controversial saying Army physical training (PT) is not going to get the results the subject wants. Additionally, is this a good goal if it would be achieved by just doing what we already do day-to-day? NO! A good goal is action oriented. To truly be a goal and not a conclusion, we need to have to fight for it. In this example, we can improve our goal as such: I WILL max the ACFT leg tuck by improving my rep count to 20 reps. I will do this by completing 20 extra pull-ups and 40 extra sit-ups every day after PT. I would also like to draw attention to the change in wording — from I want to I will. It’s a small change, but it adds ownership and purpose to goal. Realistic goals require self-reflection. This is not so much a written part of our goals, but an honest assessment to ensure that we are not setting ourselves up for failure. I figure most of you scoffed when we kept “maxing something” as part for the goal of someone who cannot yet achieve the standard. While leaders should not discourage development on the parts of our subordinates, we should make sure they are able to develop at a reasonable rate. We should not tell the subject that maxing the ACFT is impossible, but we may need to encourage them to make that a short or even longterm goal. Let’s revise our subject’s goal to: I will increase my ACFT leg-tuck score from 0 (0 reps) to 70 (5 reps) by completing 20 extra pull-ups and 40 extra crunches at the end of PT every day. I also would like to mention that as a leader, you will have very large say in what is realistic for your subordinates. Whether you mean to or not, you serve as a gate to many goals such as schools or special programs for your Soldiers. A funny story I bring up is that when I took my platoon and Spring 2022 INFANTRY 39 PROFESSIONAL FORUM Near Short Personal Professional Physical Financial Example Goal Sheet asked how many of my Soldiers wanted to go to Ranger School, over half raised their hands. After I sent the first one, the number of volunteers dropped to two. I asked my NCOs what happened and discovered that it had been over a year since anyone from the platoon had gone because of the paperwork nightmare associated with brigade schools. None of the Soldiers thought it was realistic for them to go, so they had no problem advertising Ranger School as goal. As a leader, find out what your subordinates believe to be realistic and use that to help them. Develop goals that will further their interests, not just sound good on paper. We need to make sure that we are not holding our Soldiers back, but we also need to make sure that their goals are driving them to achieve something. Lastly, we need to give our subject’s goal an expiration date. The number one reason I see Soldiers failing to achieve their goals is that they are waiting until they are “ready.” There will always be something we can do to be more ready to achieve something, so this is a terrible way to determine when we will achieve our goals. I always make my Soldiers choose a specific date they intend to accomplish their goals by. In the case of our subject, the last piece of their goal Long will be added as such: I will increase my ACFT leg-tuck score from 0 (0 reps) to 70 (5 reps) no later than 31 May 2022 by completing 20 extra pull ups and 40 extra crunches at the end of PT every day. Now that’s a goal! The final piece I give to my Soldiers is two-fold. Place a copy of their goals in a place where they will see them daily and have them share their goals with someone. This helps to prevent us from cheating ourselves and abandoning our goals when they get tough. For every Soldier I rate, I keep a copy of their goals sheet for us to talk about and update at each counseling. For every leader that I rate, it is my expectation that they are doing the same for their Soldiers. By identifying what our Soldiers want out of their time in the Army, we are better able to utilize their drive and motivation. By identifying their goals and helping them to improve themselves, we improve morale. No longer are Soldiers coming to work to further the goals of a leader many echelons above them that they may have never met; we are empowering them to come to work to meet their own goals. Ultimately, no one is responsible for achieving our goals besides ourselves. However, as leaders development is 100-percent our responsibility. It is a responsibility that we easily push to the back burner because it is ill defined, and I encourage you to keep a goals sheet for each of your junior leaders and include it as a part of your quarterly counseling. At the time this article was written, CPT Jacob Mooty was attending the Military Intelligence Captains Career Course (MICCC). He completed his branch detail as an Infantry officer in May 2021. His previous assignments include serving as a rifle platoon leader, headquarters and headquarters company executive officer, and assistant S3 with the 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division, Fort Drum, NY. Infantry Needs Your Articles INFANTRY is always in need of articles for publication. Topics for articles can include information on organization, weapons, equipment, training tips, and experiences while deployed. We can also use relevant historical articles with an emphasis on the lessons we can learn from the past. Our fully developed feature articles are usually between 2,000 and 3,500 words, but these are not rigid guidelines. We prefer clear, correct, concise, and consistent wording expressed in the active voice. When you submit your article, please include the original electronic files of all graphics. Please also include the origin of all artwork and, if necessary, written permission for any copyrighted items to be reprinted. Authors are responsible for ensuring their articles receive a proper security review through their respective organizations before being submitted. We have a form we can provide that can aid in the process. Find our Writer’s Guide at https://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/about.html. For more information or to submit an article, call (706) 545-6951 or email us at usarmy.benning. tradoc.mbx.infantry-magazine@army.mil. 40 INFANTRY Spring 2022 The SFAB: A Lieutenant’s Experience 1LT CHRISTOPHER WILSON A s I inprocessed into the 2nd Security Force Assistance Brigade (SFAB) at Fort Bragg, NC, last summer, I anticipated running into at least a few peer-lieutenants. It did not take many double-takes and greetings of “So, you’re the LT,” before I realized that I was the singular variable in the 2nd SFAB’s lieutenant trial experiment. I immediately assumed that my relative inexperience would be a great weakness here, but I was wrong. SFAB is structured so that everyone adds a niche capability to the team, one’s unconventional experiences become his or her value-added. I was not even in the organization for two weeks when I walked in on a battalion meeting at the tactical operations center (TOC) during a live-fire exercise (LFX). CSM Jacob D. Provence immediately turned to me and said, “Sir, I’m so glad you’re here. You know why? Because you’ve got fresh eyes. Tell us what you think about this [situation].” Now a whole room of senior or at least disparately experienced Soldiers stare at you expecting you to provide them with something worthwhile. That’s what it is to be an advisor. the scope of responsibility of a headquarters and headquarters company executive officer (XO)? I experienced the breadth and depth of leadership styles, a Joint Readiness Training Center Rotation (JRTC) rotation, and even some training with the 5th Special Forces Group and 75th Ranger Regiment. But completing a training cycle just to start a new training cycle is not exactly motivating. So, when I received an offer to broaden with the 2nd SFAB as it geared up to deploy across Africa, I seized it. My former brigade in the 101st did not deploy while I was with them. That is a great thing for our country, but I nonetheless felt like I had missed out, both in how I had anticipated serving and on the tactically and logistically formative experiences of a deployment. Readiness can be a dreaded buzzword. It is the strategic competition mission of the brigade combat team (BCT) and that will not change Fast forward to present-day North Africa where I am partnered with the commander of a foreign special forces battalion against al Qaeda and ISIS-affiliate terrorist cells. More than broadening, the SFAB experience is the definition of mutual force multiplication. Our allies receive our assistance, and advisors gain invaluable experience at echelons of responsibility implausible in any other conventional assignment. Then we bring that experience with us back into the regular force. After growing up with the backdrop of the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) for 20 years, today’s combat arms junior officers did not commission in the hope of deploying to Fort Irwin, CA; Fort Polk, LA; or Hohenfels, Germany. Many even based post preferences off of who was on the patch chart. Make no mistake, I loved my time in the 101st Airborne Division. What Infantry LT could ask for more than 15 months as a platoon leader, a few free reps as an assistant operations officer, and Photos courtesy of author A Security Force Assistance Brigade advisor assesses partner forces at the range. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 41 PROFESSIONAL FORUM until the next conflict which could be tomorrow or long after we retire. SFABs are the only conventional units designed to deploy in war, peace, and everything in between. As the GWOT era ends, SFABs will do exactly what they are designed to do and keep moving the strategic ball down the field, while BCTs will do exactly what they are designed to do by maintaining readiness. Both are necessary and both build upon each other. In the last year alone, the Security Force Assistance Command (SFAC) deployed advisor teams to 41 countries and is only in its initial phases of “building” its reach as our allies’ preferred partners.1 My experiences here in North Africa and the logistical lessons learned in moving advisors, weapons, and equipment — as well as building up a footprint off of an economy — have been an amazing learning opportunity. Not only is it personally fulfilling, but the lessons learned will help me better lead and serve down the line. That is how SFAB is designed, not as a branch transfer like special operations but as a branchcomplementary broadening opportunity. SFABs enable top performers to broaden outside of the BCT training cycle for a stint before returning them with the most up-to-date schooling, deployment experience, and exposure to joint, multinational, and multi-domain processes. All things in perspective, my experience is admittedly abnormal. For combat arms officers, an SFAB assignment is designed to be a broadening opportunity post Maneuver Captains Career Course (MCCC) as either a battalion advisor team (BAT) assistant S3 or a company advisor team (CAT) senior operations advisor (basically an XO). It has a utilization tour of 18-24 months, though they employ the advisor attribute of flexibility in that as well with no additional service obligation (ADSO). Post command, SFAB mimics the 75th Ranger Regiment insofar as the broadening opportunity is for command positions at echelon from team leaders (post-command captains or majors) to brigade commanders. However, one of the greatest benefits of such a new, diverse, and relatively small organization is its openmindedness. The only thing that makes my path here unique is my rank, not that they worked individually to bring me onto the team. In a May 2019 U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) article about the 1st SFAB’s first deployment to Afghanistan, its commander, BG Scott A. Jackson (who is now the SFAC CG, MG Jackson), said that “the key to our success is the talented, adaptable, and experienced volunteers who serve in this brigade.”2 I could not agree more. One of the best broadening aspects of the SFAB option to a combat arms junior officer is exposure to soft elements of the Army outside of the usual BCT structure. The majority of them are more than a cut above. Learning their backgrounds and capabilities will undoubtably enhance our ability to integrate them both on staff and in command. As an example of the caliber of advisor I have the privilege 42 INFANTRY Spring 2022 Locations of Security Force Assistance Brigades of working with, allow me to introduce the only advisor on the team younger than me: our Intelligence NCO, SSG Janay D. Walker. Not only did she graduate high school before most kids are even eligible for a driving permit, but she also had already deployed with the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and turned down the Civil Affairs pipeline to be an advisor in the 2nd SFAB. It is not just the soft skills; my team is also composed of five Ranger-qualified Infantry Soldiers. My company commander, MAJ Jacob M. Phillips, brings SOCOM experience to the table from his time with Ranger Regiment; my battalion commander, COL Christopher J. Ricci, brings U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) experience; and my brigade commander, COL Michael P. Sullivan, is a Green Beret. Such diversity not only makes this experience truly broadening, it directly enables our mission.3 Name another conventional organization in which a battalion deploys 12 teams across an area of responsibility that spans a Combatant Command with missions so diverse as to require a battalion team to advise and assist at the joint and diplomatic level, a maneuver team to do the same with an airborne commando unit, and a company team to integrate completely with a foreign special operations command. Yet here we are. Candor as the eighth Army Value, not all advisors are created equal. With regard to the few subpar advisors, I believe it is just a matter of refining the systems we already have in place: from making advisor selection universal for all advisors, to emphasizing interpersonal tact and personal initiative as essential selection criteria, to utilizing the relief for standards (RFS) protocol for underperformers. Like all selective organizations, the quality of advisor we retain today will impact the quality of advisor we recruit tomorrow. SFABs can be the most elite organizations in U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM) and are in the most unique position of then returning Soldiers with force-multiplying schools and skills throughout it. One of the downsides of SFAB’s novelty is the lack of or even misinformation on it. We are neither a BCT nor Special Forces (SF). That said, we are similar to SF insofar as we operate in small, specialized, senior, and regionally aligned teams. However, where SF trains and assists nonconventional forces on nonconventional tactics, SFAB partners, advises, and assists on the conventional side (even sometimes with nonconventional partner forces). Our mission here with a North African special forces group demonstrates the synergy between our organizations.4 For example, an SF Joint Combined Exchange Training (JCET) team recently rotated through to train them in close-quarters combat (CQB). It was advisors’ persistent partnership, however, which institutionalized that knowledge and resourcing through sustainable training programs before, during, and after the JCET rotation. Unlike a BCT, SFAB is a decentralized organization. It holistically employs mission command. Our mission sets are often ambiguous and usually follow the “one captain, one country, one team” structure. My experience through our pre-deployment train-up was one of an organization that actually trains to standard and not to time, and the small size and seniority of advisor teams tends to filter out many (but not all) of the time-consuming Soldier problems. There are no redundancies on the team. If an advisor does not perform, it weighs the whole team down, which is why the quality of advisor is so crucial. In MG Jackson’s words, “every advisor is a great Soldier, but not every Soldier is a great advisor.”5 What is the most underrated contribution to success as an advisor? Communication. The greatest obstacle to our mission so far has been the language barrier. It is no issue with our senior leader and officer counterparts who speak English, but that funnels our attention toward the picture painters and away from the raw reality. If my rudimentary French capacity can bridge a bit of that gap with our current partner force’s second language, imagine what a team of fluent Arabic speakers could do with regard to rapport, trust, accurate assessments, and advising. The SFAB’s regionally-aligned and persistent partnerships literally lend themselves to language schooling, but we handicap ourselves until it is prioritized (if not mandated) across the organization. Another option that would serve this need, incubate continuity of unit culture, and enhance persistent partner relationships is to task organize a linguist advisor per team. While the American advisory mission has a surprisingly long legacy, the SFAB as an institution is very young. It is gratifying to be in an organization that is authentically trying to optimize its structures and systems. If you want to have an impact from the individual to the organizational level, this is the place. I hope the SFAB retains its flexibility and openness to growth; it is a stark contrast to the all-too-common rigidity and risk aversion across the force. My very existence here serves as evidence of its open-mindedness. Words matter. The most unconventional aspect of this article is the unqualified source writing it. Am I the unicorn for being the lieutenant advisor, or is SFAB the unicorn for inviting the perspective of its most junior officer? Either way, I am profoundly grateful for both. From deployment experience to scope of responsibility to soft skill and mission command exposure, the SFAB experience has not only given me the tools to better serve in the future, it has invigorated my desire to do so. It was an option I had not considered before, but one I am damn glad to have seized. Notes 1 Todd South, “SFAB Soldiers Are Heading out in Smaller Teams to More Places,” Army Times, 13 October 2021, accessed from https:// www.armytimes.com/news/2021/10/13/sfab-soldiers-are-heading-outin-smaller-teams-to-more-places/. 2 C. Todd Lopez, “Success of First SFAB in Afghanistan Proves ‘Army Got It Right,’ Commander Says,” Army News Service, 9 May 2019, accessed from https://www.centcom.mil/media/news-articles/ News-Article-View/Article/1842769/success-of-first-sfab-in-afghanistanproves-army-got-it-right-commander-says/. 3 The SFAB Mission Statement: To conduct training, advising, assisting, enabling, and accompanying operations with allied and partner nations. 4 More on the symbiosis of SFAB and SF on The Indigenous Approach podcast between Security Force Assistance Command Commanding General MG Scott Jackson and 1st Special Forces Command Commanding General MG John Brennan hosted by 2nd SFAB Commander COL Michael Sullivan, 11 February 2021. 5 Ibid. 1LT Christopher L. Wilson currently serves as a maneuver advisor team leader in 1st Battalion, 2nd Security Force Assistance Brigade. He previously served as a light infantry platoon leader, assistant operations officer, and headquarters and headquarters company executive officer in 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division. He commissioned into the Infantry out of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, NY, in 2018 with a bachelor’s degree in international relations. The author advises partner forces during a training event. Spring 2022 INFANTRY 43 PROFESSIONAL FORUM You Will Accomplish Nothing: The Fundamental Challenge for Soldiers Serving as Advisors in SFABs Is Understanding Success MAJ ERIC SHOCKLEY “A leader is best when people barely know he exists; when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.” In this quote by the philosopher Lao Tzu, we can find the guidance that will most likely bring success for advisors in security force assistance brigades (SFABs). Applying this quote to the role of SFAB advisors brings to light the fundamental problem of advising success. SFAB leaders and individual advisors can set the conditions for true success by recognizing that success in advising is both unseen and unrealized. This creates a situation where the more an advisor pursues success the more elusive that success becomes. This problem can create intolerable levels of ambiguity, but in reality advisors can use doctrine as a foundation to make sense of the many “unknowns” in advising missions. For Soldiers and leaders who are serving or want to serve in an SFAB, the intent of this article is to showcase this problem and offer some techniques on how to address it. Success is unseen. As the previous quote from Lao Tzu showcased, it is often best to conduct operations in ways that allow others to believe that they accomplished the task. While some people may view this cynically and assert that this is simply one person or group taking credit for someone else’s work, my assertion is that such is a limited viewpoint. The group that says “we did it ourselves” does indeed do work. An example that illustrates this is from the 1958 book The Ugly American, which was written by Eugene Burdick and William Lederer. A situation in the book details how an American spouse living in a rural area of a foreign country noticed that the locals spent a significant amount of time on sweeping the outside areas around their homes. Because the local handmade tools they used were short handled, many of them, especially the elderly, walked about in a stooped manner. To address this issue, the spouse could have ordered long-handled brooms from the United States and given them to the locals for use. However, she recognized that this solution was an unsustainable one. Instead, she found that there was a better plant several miles away from her village that was better suited for making brooms with long handles. Again, instead of presenting this as a solution to the locals, she simply made her own long-handled broom and started using it. The locals noticed, asked about it, and then went and gathered enough of the plants to make their own brooms. They also planted some of the plants in the village so that they could make new brooms whenever they needed to. So while the spouse did work at the outset, she did it in a way that allowed the locals to work also — in a self-determined way so they could say they did it themselves. According to Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 3-07.10, Advising Multi-Service Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Advising Foreign Security Forces, “…advisors likely never please their own Service with A Soldier with the 54th Security Force Assistance Brigade advises a Guyana Defence Force (GDF) soldier during a multinational training exercise on 15 June 2021 at Camp Stephenson, Guyana. Photo by SPC N.W. Huertas 44 INFANTRY Spring 2022 regard to the forces they are advising, and they never fully satisfy the demands of the FSF [foreign security forces] unit. Advisors are figuratively, and literally, caught in the middle.” It can be easier to create and present an immediate solution rather than do the protracted mental work and “soft sell” to implement a long-term solution. Doctrine highlights this challenge for advisors, as advisors are always trying to satisfy requirements from many sources. Therefore, advisors must maintain the discipline of focusing on the long-term goal. They can partially address this by using the doctrinal techniques associated with identifying objectives along with measures of performance, measures of effectiveness, and indicators to determine when they have obtained the objective. This allows leaders in SFABs to highlight progress towards success in the inevitable situation reports (SITREPs) and update briefs that units require, despite those highlights not Photo by PFC Zoe Garbarino being the usual public affairs officer (PAO)-friendly photo opportunity of a U.S. Soldier “training” a Role-players talk to an advisor team leader from the 1st Security Force Brigade during a training event at the Joint Readiness Training counterpart. Leaders and individual advisors can Assistance Center at Fort Polk, LA, on 13 January 2018. also maintain a list of “quick win” items to satisfy information requirements. For example, a team may submit issue. As stated previously, leaders start by identifying the a storyboard of an event with a photo of an NCO teaching overall objective. Field Manual (FM) 6-0, Commander and a class on machine-gun emplacement. The higher head- Staff Organization and Operations, along with other publicaquarters could see this as a task completed, even without tions, describes ways to identify problems, conduct assessknowing the background work that went into the event, such ments, and develop the desired end state. Leaders can set as several members of the team coaxing the counterpart interim objectives that nest with the long-term objective. battalion staff members over several months to get them to Setting these interim objectives allows the individual advisynchronize time, resources, and the commander’s train- sors to create a list of tangible tasks that they can plan to ing guidance, all of which will allow the counterpart unit to complete. Having this refined list provides the opportunity to plan out how best to satisfy the previously mentioned inforperpetuate these types of training events on their own. Success is unrealized. Part of the reason for creating mation requirements while maintaining a long-term focus. SFABs was to establish long-term relationships with allies and partners. These relationships will arguably allow the U.S. Army to better operate with counterparts during any future operations. Therefore, advisors must operate with the understanding that it’s unlikely they will see the counterpart’s eventual success. Advisors can do tactical small unit planning and combined operations. Their primary focus is on systems and processes of the counterpart unit as they apply to working together in future conflict scenarios. Advisors spend a significant amount of time and energy in identifying the problem, developing solutions that the counterpart can realistically implement in a sustained manner, and then assessing the results of that implementation. One example is when a counterpart unit wants to change its NCO corps to make it more like ours. To truly make this happen takes years. Issues like pay, development of a professional military education system, and change in officer culture all must be dealt with in order to achieve success. Advisors working on these kinds of problems must accept that they may only solve a very small portion of the overall problem, and they may never know if the overall plan was successful or not. Again, doctrine provides a foundation for addressing this A second aspect of how success is unrealized is in how plans change to become the counterpart’s plan. An individual advisor may develop a tentative plan, and it must then be wargamed by the team to improve it. Advisors must display the attribute of humility, one of many applicable competencies and attributes from the Army’s Leader Requirements Model (Army Doctrine Publication 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession), as their plan changes over time. That plan then must change and become the counterpart’s plan. When finally implemented, it may look very little like the original idea. Advisors must accept this and remain focused on the counterpart’s long-term success, not their own individual role in that success. Again, this is not a new idea for Soldiers. After action reviews often start with the reminder of “no thin skins.” The intent of that statement is to tactfully remind participants of the usefulness of constructive criticism. Soldiers who want to serve as advisors must be able to embrace this idea in order to achieve both personal and mission success. Success is elusive. I have described ways where success looks different as an SFAB advisor. Now I want to describe some ways that Soldiers can operate that are more likely to bring about true success when compared with more Spring 2022 INFANTRY 45 PROFESSIONAL FORUM typical methods. First, advisors must reframe their understanding of the mission. Arguably, examples from Vietnam to Afghanistan showcase the pitfalls of mainly focusing on tactical tasks and small unit operations without a complementary effort to build long-term viability. Advisors should reframe their mindset from “What can I teach my counterpart?” to “What does my counterpart need to be successful when I’m no longer here?” For example, instead of identifying that a counterpart’s unit marksmanship program is not up to U.S. Army standards and therefore running a U.S. Army-style range, the advisor should try a different way. This may be an iterative process with the counterpart that identifies the value (or lack thereof) of marksmanship excellence in the unit or the reason behind current marksmanship qualifications (e.g., a lack of weapons or ammunition or no system to reserve training resources). This work is often done one on one, behind closed doors. It is therefore not as easy to highlight but is arguably more valuable for long-term success. Second, leaders in SFABs must recognize the work that advisors are doing and have a plan to report it to a higher headquarters. SITREPs and storyboards are the usual medium, so don’t fight the format — work with it. Using the previous marksmanship example, instead of a photo showing an advisor teaching preliminary marksmanship instruction to a counterpart as part of machine-gun training, leaders could instead show a picture of an advisor and counterpart discussing range fans on a map. This second option could have a caption that highlights that they are working together, not one teaching the other. This is especially important for publicly released photos, as the messaging to the public is a factor for the counterpart. Keeping with this example, the Part of the reason for creating SFABs was to establish long-term relationships with allies and partners. These relationships will arguably allow the U.S. Army to better operate with counterparts during any future operations. Therefore, advisors must operate with the understanding that it’s unlikely they will see the counterpart’s eventual success. accompanying SITREP could highlight the multiple internal planning sessions that shaped the overt interactions with the counterpart and ultimately ensured that the marksmanship training happened. In summary, success for SFAB advisors represents a unique challenge in comparison to other conventional forces assignments in that true success must appear to be the work of the counterpart. This means that advisor successes are typically unseen, and at the individual and team level success is often unrealized. SFAB leaders and individual advisors can combat this ambiguity by reframing how they approach the mission and how they highlight progress. Serving in an SFAB can be a unique and rewarding assignment, both in spite of and because of the challenges that I’ve mentioned. To achieve success during this assignment, I recommend SFAB Soldiers start with the following fundamental, though counterintuitive, principle: the more actively you pursue success, the more elusive that success becomes. Critics may argue that advisors are still pursuing success, just in a different form. I don’t disagree. Instead, I am attempting to make the point that how we pursue that success is critical. True success is most likely when it appears that the counterpart achieved it. While it will likely feel uncomfortable, I suggest a return to the title of this article — you will accomplish nothing. And as odd as it may seem, your goal is to accomplish nothing because that maximizes what your counterparts are able to accomplish. U.S. Army photo A 2nd Security Force Assistance Brigade advisor and Ghana Armed Forces members discuss a practical exercise at Kamina Barracks, Ghana, in November 2021. 46 INFANTRY Spring 2022 MAJ Eric Shockley is a career Army logistics officer with combat deployments to Iraq, an operational deployment to Romania as a security force assistance brigade (SFAB) advisor, and an assignment as an observer-coach-trainer at Fort Polk, LA. He is currently serving as the executive officer for 6th Battalion, 4th SFAB at Fort Carson, CO. Death on the Road to Osan: Task Force Smith CPT CONNOR MCLEOD T he first ground battle between American and North Korean forces during the Korean War ended in a North Korean victory, a distinct difference from the performance of the U.S. military that fought on multiple fronts in World War II and contributed to the defeat of the Axis powers.1 Task Force (TF) Smith lost at the Battle of Osan on 5 July 1950 because it did not appropriately use the characteristics of the defense (specifically disruption, flexibility, and operations in depth) and one of the five military aspects of terrain (key terrain) against the Korean People’s Army (KPA). The strategic scene in which TF Smith fought at Osan was set in the aftermath of World War II. President Harry Truman and his Secretary of Defense, Louis Johnson, drastically cut military spending in the interest of transitioning to postwar life. American occupation forces in Asia were among the hardest hit as “U.S. infantry divisions in the Far East were shorn of 62 percent of their firepower... with barely a forty-five day supply of ammunition.”2 The insufficient funding meant maneuver units did not conduct large-scale field exercises, essentially reducing them to constabulary units in the local area rather than America’s first line of defense against communist aggression in Asia.3 The Korean War began on 25 June 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea with seven KPA divisions and more than 150 T-34 tanks and 200 aircraft against eight Republic of Korea (ROK) Army divisions.4 North Korean forces quickly routed the ROK divisions defending the capital city of Seoul and entered the city’s suburbs by the morning of 27 June (see Map 1).5 General of the Army Douglas MacArthur recommended President Truman order air, ground, and naval forces to South Korea as soon as possible to assist the ROK Army.6 President Truman saw Korea as an opportunity to prevent unopposed communist expansion and set an example for nations bullied by “stronger communist neighbors” to stand and fight.7 Secretary of State Dean Acheson wrote that America’s “internationally accepted Map 1 — The North Korean Invasion, 25-28 June 1950 position as the protector of South Korea” was at stake.8 President Truman deliberated over information as it came in and decided in favor of military action under a United Nations (UN) resolution. The vote passed, aided by the fact that the Soviet Union, one of the five veto powers on the UN Security Council, was absent from the vote because “it was treating the crisis as a Korean internal affair.”9 Air and naval forces of the United States and Great Britain launched strikes against North Korean forces attacking south, particularly around Seoul, starting on 27 June.10 MG William F. Dean’s 24th Infantry Division (ID), on occupation duty in Japan, received orders from Eighth Army on 30 June to prepare for deployment to South Korea.11 MG Dean selected the 21st Graphics from South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (June-November 1950) by Roy E. Appleman Spring 2022 INFANTRY 47 LESSONS FROM THE PAST driving past South Korean refugees fleeing south.18 The first thing LTC Smith conducted at Osan was a reconnaissance with key leaders from 1-21 IN on 4 July and identified where to establish his defense, “an irregular line of hills stretched across the main road [to Osan] and the railway to the east” (see photo below).19 At the time of its airlift from Japan, TF Smith consisted of B and C Companies and assorted Headquarters Company elements: 406 men with small arms, “two 75mm recoilless guns, two 4.2-inch mortars, and some 2.36-inch bazookas.”20-21 There were experienced men throughout TF Smith to provide a steady core. Including LTC Smith, “about onethird of the officers…[and] one-half of the non-commissioned officers were World War II veterans, but not all had been in combat. Throughout the force, perhaps one man in six had combat experience.”22 Battery A, 52nd Field Artillery (FA) Regiment, consisting of six 105mm howitzers with six armordefeating high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) rounds under the command of LTC Miller Perry, joined 1-21 IN on 4 July.23 TF Smith established positions on a ridge overlooking the road from Suwon to Osan. One platoon from B/1-21 IN was to the west of the road with the rest of B and C/1-21 IN to the east of the road. A/52 FA was located approximately 1 kilometer south of the infantry positions, except for one howitzer emplaced forward with the six HEAT rounds (see Map 3 for reference).24-25 LTC Smith and his men faced KPA forces consisting of 33 Soviet-built T-34 tanks and 4,000 seasoned infantry from the KPA 4th Division, with supporting artillery.26 Map 2 — 28 June - 4 July 1950 Infantry Regiment (the “Gimlets”) because it was the closest 24th ID element to Korea. The Gimlets also had the strongest esprit de corps among the regiments and performed the best in exercises with the division’s limited training resources in Japan.12 Concurrently, the KPA 4th Division attacked south along the rail-highway axis from Yongdungp’o toward Suwon. It defeated the 5th ROK Regiment fighting a delaying action on 4 July and rapidly advanced toward Osan (see Map 2).13 At approximately 0730 on 5 July, TF Smith spotted the first North Korean tanks coming from Suwon unaccompanied by infantry. Battery A fired a high-explosive (HE) barrage at a range of approximately 1,800 meters with no effects.27 The recoilless rifles opened fire at approximately 650 meters and received fire from KPA T-34 cannons and machine guns in return. American bazooka teams waited until the KPA tanks were at point-blank range and then knocked out two T-34s.28 Unfortunately, most of the rockets, as well as the 75mm recoilless rifles, were ineffective. 2LT Ollie Conner, awarded the Silver Star after the battle for his actions, “fired 22 rockets, from about fifteen feet... and cursed as his shots... COL Richard Stephens, commander of the 21st Infantry Regiment, alerted LTC Charles Smith, commander of the 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment (1-21 IN), for deployment at 2245 on 30 June.14 LTC Smith, a veteran of the Guadalcanal campaign in World War II, assembled his troops on 1 July.15 Smith had six U.S. Air Force (USAF) C-54s available for air movement, meaning he could move only two of his three rifle companies and half of his 75mm recoilless rifles and 4.2-inch mortars from the Headquarters Company.16 MG Dean met LTC Smith on the tarmac at Itazuke Airfield before the battalion flew to Pusan and simply said, “Head for Osan. We’ve got to block the main Seoul-Pusan road as far north as possible.”17 TF Smith made a rail movement from Pusan to Taejon on 2 July and a vehicle movement from Taejon north toward Osan, Task Force Smith's position straddled the Osan-Suwon Road. 48 INFANTRY Spring 2022 failed to cripple the tankers.”29 The remaining T-34s passed through the infantry’s positions and moved toward the artillery battery. Battery A’s lone forward howitzer destroyed two tanks with HEAT rounds before T-34 fire destroyed it.30 The remainder of A/52 FA “traded howitzer for tank, destroying five enemy tanks [including those destroyed by the HEAT howitzer], and losing five howitzers.”31 LTC Perry gathered artillerymen into bazooka teams as a last-ditch effort to stop the enemy armor. These bazooka teams destroyed two T-34s, and LTC Perry was wounded in the leg by North Korean fire in the process. The KPA T-34s did not stop to engage A/52 FA and sped toward Osan.32 At this point, TF Smith suffered around 20 killed and wounded from enemy fire.33 LTC Smith used the lull in the battle to improve his companies’ positions and communications as well as conduct hasty weapons maintenance.34 A column of KPA trucks and dismounted infantry appeared from Suwon about an hour later. At 900 meters, “Task Force Smith ‘threw the book at them.’”35 The KPA infantry suffered heavy casualties as artillery and mortars “landed smack among the trucks… while 50-caliber machine guns swept the column.”36 Three T-34s came forward from the column and fired on the Americans. North Korean infantry began to flank TF Smith, establishing support-by-fire positions on hills to the east and west.37 Fire from Hill 1230 in the west forced LTC Smith to move the B Company platoon on the west side of the road to the main company position (see Map 3).38 Smith’s executive officer, MAJ Floyd Martin, moved all extra ammunition and the 4.2-inch mortars forward from their previous positions closer to the “battalion command post…[in] a tighter defense perimeter on the highest ground east of the road.”39 LTC Smith lost radio communications with his artillery at around 1100 because his radios and communications wire were damaged or destroyed by the previous night’s rain and enemy fire.40 He could not effectively call for fire on the KPA machine guns firing from the high ground or the infantry maneuvering on his position. Nevertheless, TF Smith kept KPA infantry at bay with small arms and mortar fire until 1430 when LTC Smith realized the task force’s situation was untenable.41 In LTC Smith’s own words, “In an obviously hopeless situation… I was faced with the decision: what the hell to do? To stand and die[?]… I chose to get out, in hopes that we would live to fight another day.”42 Faced with no other choice, LTC Smith gave the order to withdraw.43 B Company covered CPT Richard Dashmer’s C Company, battalion headquarters, and the medical section’s withdrawal off the ridge toward Osan.44 Once C Company established a support-by-fire position near the Map 3 — Task Force Smith at Osan-Ni, 5 July 1950 railroad tracks running to the south, it covered B Company’s movement with small arms fire.45 At this point, KPA forces nearly enveloped the battalion, “but the first units… cleared a pathway… to withdraw southward in small groups.”46 The withdrawing companies left behind some of their heavy weapons, and regretfully among the TF’s veterans, their dead and around 30 non-ambulatory wounded. Despite leaders’ attempts to keep the movement as orderly as possible, some men took matters into their own hands and escaped any way they could, running across rice paddies or seeking cover from KPA patrols until darkness.47 By nightfall of 5 July, around 250 personnel from TF Smith, including LTC Smith, regrouped at Ansong and moved to Taejon the next morning.48 Smaller groups evaded KPA patrols and reunited with their units over the following days.49 After the battle, LTCs Perry and Smith said reflectively in interviews that “a few well-placed antitank mines would have stopped the entire armored column in the road.”50 There were no antitank mines in TF Smith or all of Korea.51 TF Smith suffered approximately 150 casualties killed, wounded, or missing during the Battle of Osan.52 North Korean casualSpring 2022 INFANTRY 49 LESSONS FROM THE PAST ties number around 40 killed and 90 wounded and between four and seven T-34s.53-54 TF Smith’s stand at Osan gave the 24th ID’s 34th Infantry Regiment enough time to deploy to Korea and establish defenses south of Osan, but actions of the 34th Infantry Regiment and other 24th ID elements were all too similar in the first weeks of the Korean War due to piecemeal employment and KPA momentum.55 They create conditions by disrupting enemy long-range fires, sustainment, and command and control. These disruptions weaken enemy forces and prevent any early enemy successes. Operations in depth prevent enemy forces from maintaining their tempo. In the defense, commanders establish a security area and the main battle area (MBA) with its associated forward edge of the battle area (FEBA).”63 TF Smith’s defeat at Osan stems from its inappropriate use of the characteristics of the defense, specifically disruption, flexibility, and operations in depth, and the military aspect of terrain of key terrain. Disruption, as defined in Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 3-90, Offense and Defense, is when “defending forces seek to disrupt attacks by employing actions that desynchronize an enemy force’s preparations.”56 Disruption means taking action to prevent the enemy’s plan or operation from working smoothly. TF Smith failed to practice disruption because it did not effectively employ anti-armor weapons to destroy significant amounts of KPA armor.57 This shortcoming led to defeat because TF Smith did not force an early deployment of forces or stop the North Korean movement and massing of combat power. The task force also displayed a lack of disruption because it did not desynchronize the enemy’s operation. Besides the forces manning battle positions along the Suwon-Pusan Road, there were no other effects to block or disrupt the North Korean advance.58 This deficiency was critical because North Korean tanks easily punctured TF Smith’s positions due to ineffective direct and indirect fires targeting the tanks’ movement. Also, North Korean infantry moved unimpeded near TF Smith’s positions once the North Korean supportby-fire positions achieved suppression.59 Operations in depth means there are multiple parts of the battlefield to fight the enemy and prevent them from gaining an advantage. TF Smith did not implement operations in depth because it employed no security or reconnaissance elements forward of its position to provide early warning or disrupt enemy forces and their warfighting functions.64 The inability to achieve this characteristic was pivotal because TF Smith had no information about the enemy situation and did not observe the enemy force until it was a few kilometers away. LTC Smith arrayed his two companies on line with each other along a ridge.65 He violated operations in depth because he did not organize a reserve force or have subsequent battle positions between the infantry and Battery A. LTC Smith had insufficient forces available to constitute a reserve or depth, so he had to place his companies on line to establish the defense. This decision allowed the North Koreans to penetrate and bypass TF Smith’s battle positions, leaving no American forces between the North Koreans and the unprotected artillery battery and Taejon.66 As for flexibility, ADP 3-90 states that “defensive operations require flexible plans that anticipate enemy actions and allocates resources accordingly. Commanders shift the main effort as required. They plan battle positions in depth and the use of reserves in spoiling attacks and counterattacks.”60 Flexibility is having multiple options available to adapt to the enemy’s actions. TF Smith’s plan to make a stand against a mobile, armored threat and lack of subsequent battle positions broke the characteristic of flexibility. The inflexible nature of TF Smith’s defense was a factor in the loss at Osan because it confined TF Smith to battle positions on the ridge and limited the ability to mount a counterattack or retrograde if necessary. There was also no contingency or anticipation if North Korean tanks penetrated TF Smith’s positions, which contradicted the characteristic of flexibility.61 The absence of flexibility in the defense influenced the outcome of the battle because once the infantry lost radio communications with the artillery, A/52 FA knew North Korean tanks were approaching only when they came into view. The belief that the enemy tanks would turn around after being engaged by the infantry meant the artillerymen had to quickly create ad hoc bazooka teams that had little effect.62 Operations in depth, as defined in ADP 3-90, “is the simultaneous application of combat power throughout an area of operations. Commanders plan their operations in depth. 50 INFANTRY Spring 2022 ADP 3-90 defines key terrain as “an identifiable characteristic whose seizure or retention affords a marked advantage to either combatant.”67 In layman’s terms, key terrain is a place or point that gives one side the advantage over the other if it is controlled or acted upon. TF Smith incorrectly utilized and recognized key terrain because it did not occupy, or at least deny enemy access to, the high ground around its battle positions. The North Koreans established support-by-fire positions on hills to the east and west of the task force’s positions.68 This event was influential because the enfilade fire that came from those hills allowed the North Korean infantry to maneuver on the flanks and into dead space to envelop TF Smith in its battle positions.69 North Korean forces defeated LTC Smith and his troops at Osan on 5 July 1950 in the first ground battle between American and North Korean forces. TF Smith managed to stop the North Korean advance for several hours, but it was not enough to slow the momentum as the North Koreans continued through Osan to P’yongt’aek.70 TF Smith failed at the Battle of Osan on 5 July 1950 due to the poor use of the characteristics of the defense, specifically disruption, flexibility, and operations in depth, and the military aspect of terrain key terrain, against the Korean People’s Army. Notes 1 Bill Sloan, The Darkest Summer, Pusan and Inchon 1950: The Battles that Saved South Korea – and the Marines – From Extinction (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2009), 22-23. 2 Ibid, 22. 3 Roy K. Flint, “Task Force Smith and the 24th Division: Delay and Withdrawal, 5-19 July 1950,” in America’s First Battles: 1776-1965, ed. Charles E. Heller and William A. Stofft (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1986), 270-274. 4 Allan R. Millett, The War for Korea, 1950-51: They Came from the North (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2010), 85-89. 5 Roy E. Appleman, South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (JuneNovember 1950) (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1961), 29-31. 6 Sloan, The Darkest Summer, 19. 7 Bevin Alexander, Korea: The First War We Lost (NY: Hippocrene Books, 1998), 33. 8 Ibid. 9 Ibid, 42-43. 10 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 50-52. 11 Ibid, 59. 12 Flint, “Task Force Smith and the 24th Division,” 271- 276. 13 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 54-58. 14 Richard W. Stephens, “21st Infantry Regiment War Diary for the Period 29 June to 22 July 1950, from 292400 June 1950 to 302400 June 1950,” in United States Army 24th Infantry Division Unit War Diaries from June to November 1950 (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1950). 15 T.R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness (NY: Macmillan, 1963), 65. 16 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 60-61. 17 George B. Busch, Duty: The Story of the 21st Infantry Regiment (Sendai, Japan: Hyappan Printing Company, 1953), 20. 18 Korea – 1950 (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1952), 14. 19 J. Lawton Collins, War in Peacetime: The History and Lessons of Korea (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1969), 47. 20 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 60-61. 21 John Toland, In Mortal Combat: Korea, 1950-1953 (NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1991), 77. 22 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 61. 23 Collins, War in Peacetime, 47-50. 24 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 66-67. 25 Collins, War in Peacetime, 49-50. 26 Shelby P. Warren, A Brief History of the 24th Infantry Division in Korea (Tokyo: Japan News, 1956), 4. 27 Toland, In Mortal Combat, 80. 28 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 69. 29 Busch, Duty, 21. 30 Collins, War in Peacetime, 50-51. 31 Busch, Duty, 20. 32 Collins, War in Peacetime, 51. 33 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 70. 34 Collins, War in Peacetime, 51. 35 Busch, Duty, 21. 36 Collins, War in Peacetime, 52. 37 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 73. Collins, War in Peacetime, 52. Appleman, South to the Naktong, 73. 40 Ibid, 70. 41 Alexander, Korea, 60-61. 42 Busch, Duty, 22. 43 Stephens, “21st Infantry Regiment War Diary for the Period 29 June to 22 July 1950,” 2. 44 Busch, Duty, 21. 45 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 74-75. 46 Stephens, “21st Infantry Regiment War Diary for the Period 29 June 1950 to 22 July 1950.” 47 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 74-75. 48 Busch, Duty, 22. 49 Alexander, Korea, 62. 50 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 72. 51 Ibid, 72. 52 Collins, War in Peacetime, 54. 53 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 76. 54 Alexander, Korea, 58-60; Appleman, South to the Naktong, 69-76; Collins, War in Peacetime, 50-52; and Millett, The War for Korea, 137-138. There are conflicting numbers of T-34s destroyed. Most cited sources report four T-34s destroyed, including Appleman, Collins, and Millett. According to Alexander, TF Smith destroyed four T-34s and damaged three more to the point of being combat ineffective. 55 Collins, War in Peacetime, 55. 56 Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 3-90, Offense and Defense, July 2019, 4-1. 57 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 72. 58 Ibid, 65-68. 59 Ibid, 73. 60 ADP 3-90, 4-2. 61 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 70. 62 Ibid, 70-71. 63 ADP 3-90, 4-2. 64 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 66-67. 65 Ibid. 66 Busch, Duty, 21. 67 ADP 3-90, 3-10. 68 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 73. 69 Alexander, Korea: The First War We Lost, 60-61. 70 Appleman, South to the Naktong, 79. 38 39 At the time this article was written, CPT Connor McLeod was attending the Maneuver Captains Career Course at Fort Benning, GA. His previous assignments include serving as a rifle platoon leader, mortar platoon leader, and assistant S3 with 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, Joint Base Lewis-McChord, WA. He earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Michigan State University. New from the U.S. Army Center of Military History The Conflict with ISIS: Operation Inherent Resolve, June 2014 - January 2020 This publication, written by Mason W. Watson, chronicles how a U.S.-led coalition fought against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) — a terrorist organization that, at its height, controlled a span of territory in Iraq and Syria the size of Kentucky. Beginning in August 2014, a campaign of targeted airstrikes slowed ISIS’s offensive momentum and gave U.S. military advisers a chance to help rebuild the shattered Iraqi Security Forces. With coalition assistance, the Iraqis then liberated their country in a series of major operations that culminated in the battle for Mosul (2016-2017), one of the largest urban battles in recent history. The narrative further describes how U.S. Army conventional and special operations forces enabled local partners, including the Syrian Democratic Forces, to retake ISIS-held areas of eastern Syria. By January 2020, Iraqi and Syrian forces — supported by U.S. airpower, armed with U.S. equipment, and trained and assisted by U.S. military advisers — had defeated ISIS on the battlefield and ended its pretentions to statehood. Find this publication online at https://history.army.mil/catalog/pubs/78/78-2.html. 1 Spring 2022 INFANTRY 51 Guidelines for the Leader and the Commander By GEN Bruce C. Clarke Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2021 (reprint), 117 pages Reviewed by LTC (Retired) Rick Baillergeon I f you are looking for a book on leadership, you know there are an incredible amount of options out there. How do you select the “right one” with the seemingly endless possibilities? The savvy reader knows you must do your homework and conduct the requisite research. One of the key aspects of this is to establish the credentials of the author. Do they have the necessary background, experience, and expertise to craft a beneficial volume on a difficult subject — leadership? An author who unquestionably possesses these characteristics is the late GEN Bruce C. Clarke who addresses leadership (and much more) in his superb volume, Guidelines for the Leader and the Commander. Let me highlight those exceptional credentials below. GEN Clarke served in the U.S. Army from 1917 to 1962 and held the ranks of private to four-star general. During his long career, he commanded a long list of formations in war and peacetime. These include commands at the division and corps level, U.S. Army Pacific, Seventh U.S. Army, U.S. Army Europe, and U.S. Continental Army Command. With all his accomplishments, he is perhaps best known for his leadership during the Battle of the Bulge where his actions and decisions were critical in halting the German advance. In total, this is clearly someone who walked the walk and can justifiably talk the talk on a myriad of topics including leadership. Before delving into the many virtues of the book, let me address the history of the volume. Guidelines for the Leader and the Commander was first published in 1963. The volume was revised in 1964 and 1968 before its final edition was published in 1973. For well over 40 years, the book remained under the radar for new readership. Then in the fall of 2020, the book was featured on a highly popular podcast, and interest in GEN Clarke’s thoughts rose dramatically. The original publisher (Stackpole Books) saw this renewed interest and reprinted the 1973 edition in the spring of 2021, thus providing the volume for a new generation of readers. Within this book, GEN Clarke captures these 45 years of experience. He does this by combining transcripts of his speeches and lectures, excerpts of his previous works, and his thoughts on various subjects into a cohesive volume. GEN Clarke divides these into four distinct sections: Leadership 52 INFANTRY Spring 2022 and Command, Training, Operations and Administration, and A Final Word (capturing miscellaneous topics). Within each section, readers will find an incredible amount of nuggets to reflect upon. Some of these will be things that simply reinforce your own thoughts or support actions you already perform. Others may spark fresh views or generate new techniques or behavior. Not only will this text benefit a military audience, but those in the civilian world will also find numerous takeaways from the volume. There are two factors which greatly assist the reader in gleaning these nuggets from the volume. First, is the writing style. This a book where you feel you are in an office with him and he is having a conversation with you. He also promotes a dialogue with the reader by having the ability to encourage them to reflect on points he makes. This reflection time is invaluable. The other factor is the book’s organization. GEN Clarke has organized his volume into bite-size chunks for the reader. Inside the aforementioned four major sections, GEN Clarke then divides his discussion into more specific chapters. Finally, he provides further specificity by dividing each chapter into numerous smaller discussion areas. These small sub-chapters truly promote reflection and comprehension. There are two additional subjects I would like to address pertaining to the volume. The first is the dedication GEN Clarke places at the beginning of his book. Even nearly 60 years ago (when the volume was written), he sensed the way people were becoming enamored by technology. Consequently, he dedicates his book to the “Ground Combat Soldier.” Within this dedication, he states, “It will be a sorry day for all mankind in this supersonic nuclear age of ours should the ground combat soldier ever be deprived of his rightful place in the hearts and minds and military forces of his people.” Obviously, these words still ring true today. The second point I would like to address is an added bonus of the volume. I believe this book affords readers an opportunity to learn about the post-World War II and Korean War Armies. There is much you can ascertain from GEN Clarke’s words regarding the state of the force during that period. His thoughts and opinions on certain areas give a great perspective on the mindset and capabilities of that force. Some would say that a book on leadership written so long ago is no longer relevant today. They could not be further from the truth. Certainly, some of the things GEN Clarke writes on have changed over the years. However, the basic concepts and advice he provides are just as powerful today as ever. So if you are looking for that right book on leadership, I have done the research for you. This a book crafted by a Soldier and leader who is truly qualified to speak and write on the subject, and his advice should be heeded. The Infantry Creed I am the Infantry. I am my country’s strength in war, her deterrent in peace. I am the heart of the fight… wherever, whenever. I carry America’s faith and honor against her enemies. I am the Queen of Battle. I am what my country expects me to be, the best trained Soldier in the world. In the race for victory, I am swift, determined, and courageous, armed with a fierce will to win. Never will I fail my country’s trust. Always I fight on... through the foe, to the objective, to triumph overall. If necessary, I will fight to my death. By my steadfast courage, I have won more than 200 years of freedom. I yield not to weakness, to hunger, to cowardice, to fatigue, to superior odds, For I am mentally tough, physically strong, and morally straight. I forsake not my country, my mission, my comrades, my sacred duty. I am relentless. I am always there, now and forever. I AM THE INFANTRY! FOLLOW ME!